Evaluation of the Narrative Value and Experiential Quality of Urban Trails: A Case Study of the Southwest Regional Trail in Chongqing, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How can a narrative evaluation framework be developed that integrates spatial narrative value (the spatial perspective) with narrative experience (the human perspective)?

- Which indicators can quantitatively assess the spatial narrative-value elements of urban trails to identify potential high-value zones and their defining spatial characteristics?

- How can the current state and problems of visitors’ spatial narrative experience be analyzed to extract and distill their key influencing factors?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Object

2.2. Evaluation System and Data Sources

2.3. Methods and Data Analysis

2.3.1. Methods for Spatial Narrative Value Evaluation

2.3.2. Methods for Spatial Narrative Experience Evaluation

3. Results

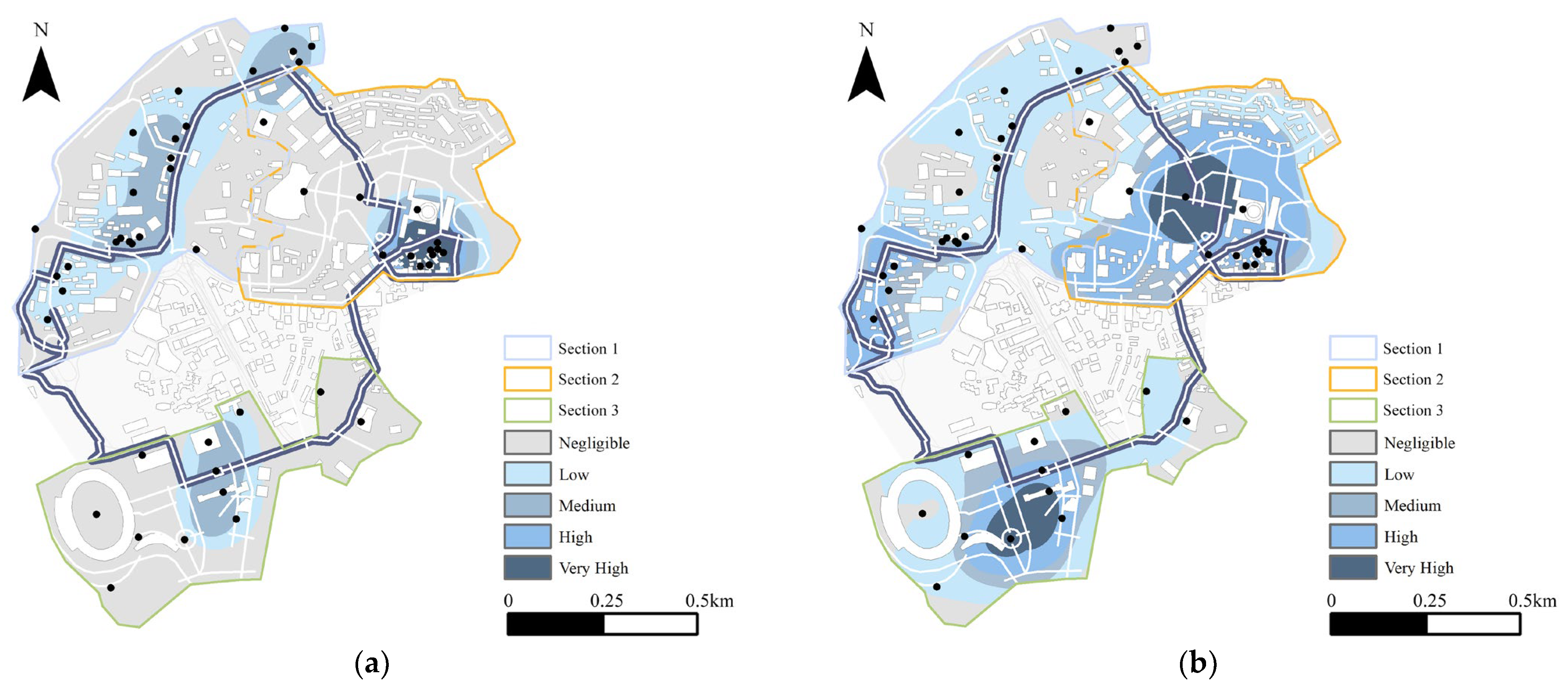

3.1. Spatial Narrative Value Evaluation

3.1.1. Spatial Narrative Resources

3.1.2. Spatial Narrative Structure

3.1.3. Spatial Narrative Effectiveness

3.1.4. Overlay Analysis and Reclassification Results

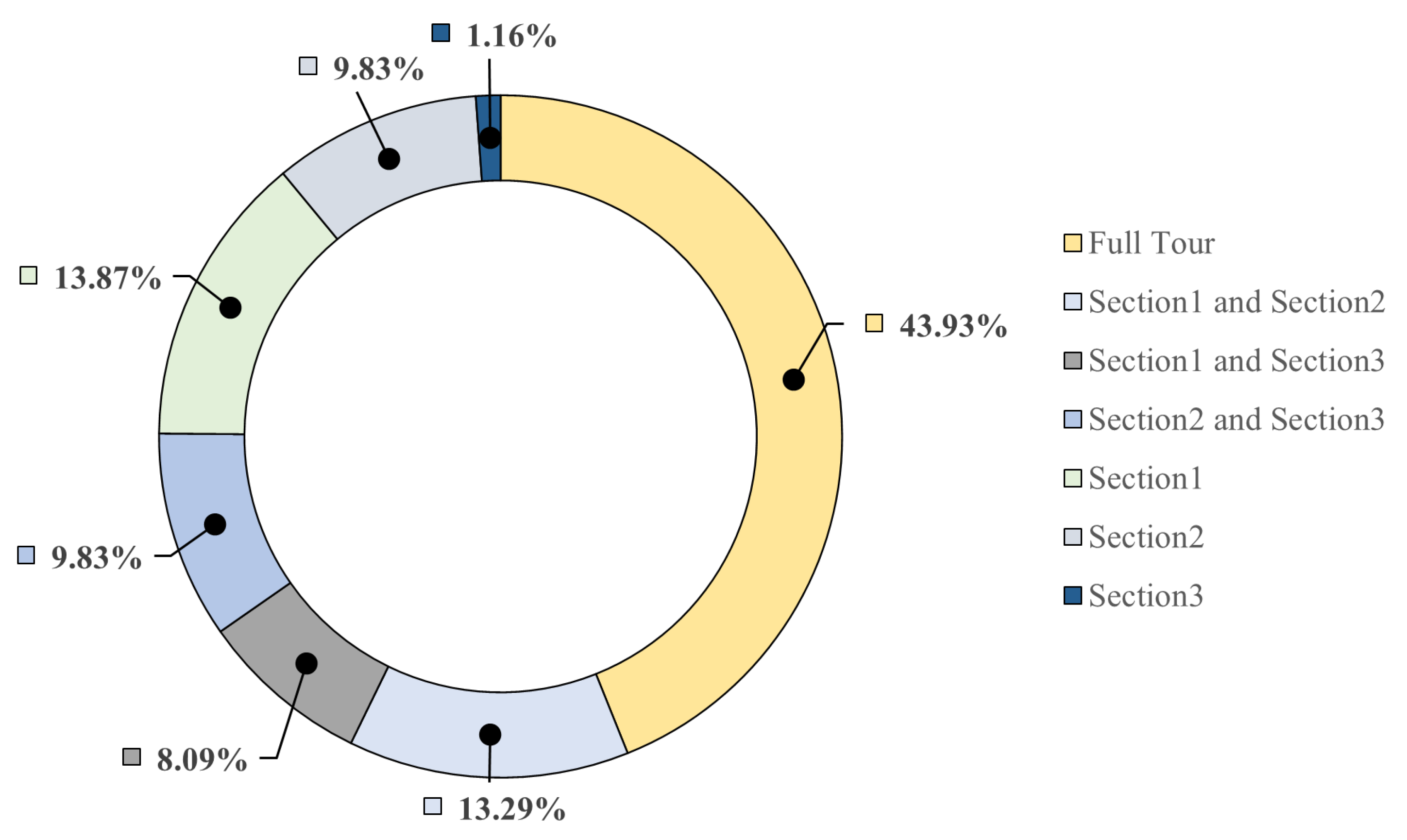

3.2. Spatial Narrative Experience Evaluation

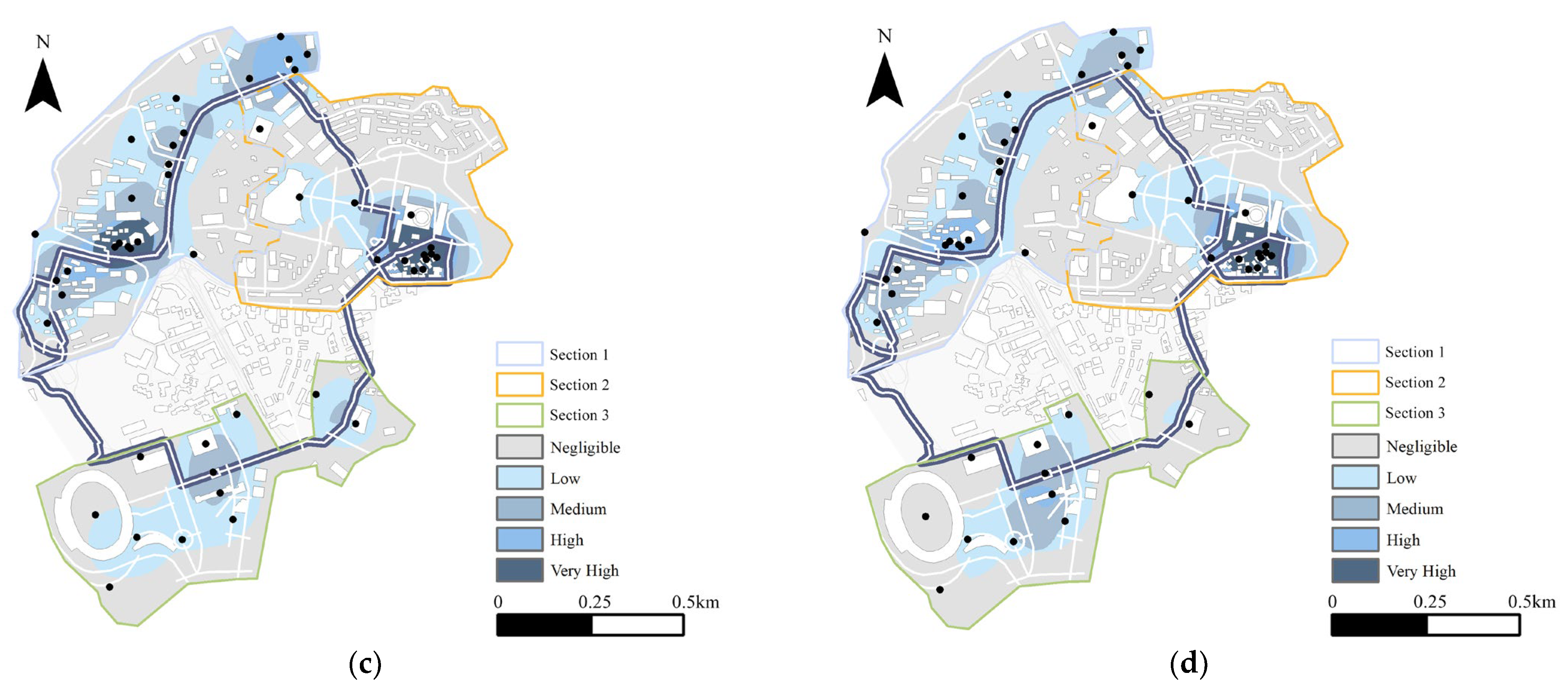

3.2.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis Results

3.2.2. ANOVA Results

3.2.3. Linear Regression Analysis Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Superior Spatial Narrative Effectiveness as a Driver of Visitation

4.2. Key Determinants of Narrative Experience on Urban Trails: Symbols, Routes, and Educational Value

4.3. Future Recommendations for Southwest Regional Trail

4.4. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HE | Historical Events Count |

| NI | Narrative Node Importance |

| NC | Narrative Node Chronology |

| RC | Route Choice |

| RI | Route Integration |

| TR | Theme Relevance |

| NG | Narrative Guidance |

| TA | Thematic Activities Count |

| SR | Narrative Symbol Richness |

| RV | Narrative Resource Visibility |

| RP | Narrative Resource Prominence |

| LC | Narrative Logic Clarity |

| TI | Narrative Thread Identifiability |

| RS | Narrative Route Selectivity |

| SC | Spatial Narrative Continuity |

| NS | Narrative Structural Situationality |

| ER | Emotional Resonance Intensity |

| CE | Cultural Educational Value |

| ID | Interaction Diversity |

| CI | Cultural Identity |

| OE | Overall Experience Evaluation |

| KDE | Kernel Density Estimation |

Appendix A

| No. | Question | Question Type | Options | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Your gender | Single choice | ○ Male ○ Female | ||||

| 2 | Your age | Single choice | ○ 18–25 ○ 26–35 ○ 36–45 ○ 46–59 ○ Over 60 | ||||

| 3 | Your highest education level | Single choice | ○ High school or below ○ College degree ○ Bachelor’s degree ○ Master’s degree or above | ||||

| 4 | Which trail section(s) have you experienced? | Multiple choice | □ Zhongshan Fourth Road Section □ People’s Assembly Hall Section □ Datianwan Section | ||||

| Likert scale (1–5) | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree | ||

| ○ 1 | ○ 2 | ○ 3 | ○ 4 | ○ 5 | |||

| 1 | The story symbols along the trail were rich and engaging. | ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 | |||||

| 2 | The space was clearly connected to the historical and cultural context. | ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 | |||||

| 3 | You are very familiar with the historical events displayed here. | ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 | |||||

| 4 | The stories told here are coherent and easy to follow. | ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 | |||||

| 5 | The space was easy to navigate and well-organized. | ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 | |||||

| 6 | You had the freedom to choose different paths or experiences. | ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 | |||||

| 7 | You could easily transition between different stories or scenes. | ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 | |||||

| 8 | You felt immersed in the story’s atmosphere. | ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 | |||||

| 9 | You felt emotionally involved in the storytelling. | ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 | |||||

| 10 | You learned something new or meaningful during the visit. | ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 | |||||

| 11 | You could interact with installations or exhibits along the trail. | ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 | |||||

| 12 | You feel more connected to the place or its culture after this experience. | ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 | |||||

| 13 | How satisfied are you with your overall travel experience? | ○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5 | |||||

References

- Zhou, H.; Chi, X.; Norman, R.; Zhang, Y.; Song, C. Tourists’ urban travel modes: Choices for enhanced transport and environmental sustainability. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 129, 104144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarin, A.; Park, E.; Xiao, Q.; Kim, S. Time to transform the way we travel?: A conceptual framework for slow tourism and travel research. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 46, 101100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D. City walk in a gap day: Potential and opportunities for tourism and leisure. Tour. Rev. 2023, 79, 1576–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, İ.; Özkar, M. Designing for spatial narration in children’s playscapes. A/Z. ITU J. Fac. Archit. 2020, 17, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, J.; Scott shafer, C. Aesthetic Responses to Urban Greenway Trail Environments. Landsc. Res. 2009, 34, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božić, S.; Tomić, N. Developing the Cultural Route Evaluation Model (CREM) and its application on the Trail of Roman Emperors, Serbia. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 17, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, D.; Sörlin, S.; Saltzman, K. Pathways to the trail—Landscape, walking and heritage in a Scandinavian border region. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr.-Nor. J. Geogr. 2021, 75, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senetra, A.; Dynowski, P.; Cieślak, I.; Źróbek-Sokolnik, A. An Evaluation of the Impact of Hiking Tourism on the Ecological Status of Alpine Lakes—A Case Study of the Valley of Dolina Pięciu Stawów Polskich in the Tatra Mountains. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization. Walking Tourism—Promoting Regional Development; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2019; p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- Panagopoulos, T.; Tampakis, S.; Karanikola, P.; Karipidou-Kanari, A.; Kantartzis, A. The Usage and Perception of Pedestrian and Cycling Streets on Residents’ Well-being in Kalamaria, Greece. Land 2018, 7, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-Pandemic Cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willberg, E.; Fink, C.; Toivonen, T. The 15-minute city for all?—Measuring individual and temporal variations in walking accessibility. J. Transp. Geogr. 2023, 106, 103521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, M.; Torreggiani, D.; Tassinari, P.; Barbaresi, A. Developing a 3D City Digital Twin: Enhancing Walkability through a Green Pedestrian Network (GPN) in the City of Imola, Italy. Land 2022, 11, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Li, Y.; Cheng, J.; Qin, Y.; Shen, G.; Li, B.; Yang, H.; Li, S. Understanding the aesthetic perceptions and image impressions experienced by tourists walking along tourism trails through continuous cityscapes in Macau. J. Transp. Geogr. 2023, 112, 103703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibaud, J.-P. Commented City Walks. WI J. Mob. Cult. 2013, 7, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Hu, X.; Song, Z.; Yuan, X. Identifying the integrated visual characteristics of greenway landscape: A focus on human perception. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, N. The role of trails in the creation of tourist space. J. Herit. Tour. 2016, 12, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóźwiak, M.; Sieg, P. Tourism Development in Post-Industrial Facilities as a Regional Business Model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R.; Sharifi, A.; Sadeghi, A. The 15-minute city: Urban planning and design efforts toward creating sustainable neighborhoods. Cities 2023, 132, 104101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Chung, W.J.; Jeong, C. Exploring Sentiment Analysis and Visitor Satisfaction along Urban Liner Trails: A Case of the Seoul Trail, South Korea. Land 2024, 13, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donahue, M.L.; Keeler, B.L.; Wood, S.A.; Fisher, D.M.; Hamstead, Z.A.; McPhearson, T. Using social media to understand drivers of urban park visitation in the Twin Cities, MN. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 175, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, S.J.; Larson, L.R.; Shafer, C.S.; Hallo, J.C.; Fernandez, M. Greenway use and preferences in diverse urban communities: Implications for trail design and management. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 172, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziejczyk, K. Networks of hiking tourist trails in the Krkonoše (Czech Republic) and Peneda-Gerês (Portugal) national parks—Comparative analysis. J. Mt. Sci. 2019, 16, 725–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, T. Narrative Environments and Experience Design: Space as a Medium of Communication, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Caquard, S.; Cartwright, W. Narrative Cartography: From Mapping Stories to the Narrative of Maps and Mapping. Cartogr. J. 2014, 51, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; McIntosh, J.; Delozier, G. GIS as a Narrative Generation Platform. In Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, Indiana, 2015; pp. 176–202. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S.; Li, X.; Yang, T. Exploration on Application of Space Syntax in Narrative Reconstruction of Memory Place. Mod. Urban. Res. 2024, 5, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, K. Tourism and the geopolitics of Buddhist heritage in Nepal. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Zhou, Y. Conducting Heritage Tourism-Led Urban Renewal in Chinese Historical and Cultural Urban Spaces: A Case Study of Datong. Land 2022, 11, 2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, N.; Jimura, T. Tourism, Cultural Heritage and Urban Regeneration: Changing Spaces in Historical Places, 1st ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nisha, B. Place and Perception: Constructing the Urban Narrative with Spatial Schemas. Available online: https://theccd.org/article/place-and-perception-constructing-the-urban-narrative-with-spatial-schemas/ (accessed on 15 October 2018).

- Hawthorne, T.L.; Toohy, K.R.; Yang, B.; Graham, L.; Lorenzo, E.M.; Torres, H.; McDonald, M.; Rivera, F.; Bouck, K.; Walters, L.J. Mapping Emotional Attachment as a Measure of Sense of Place to Identify Coastal Restoration Priority Areas. Appl. Geogr. 2022, 138, 102608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkonen, K. The “Narrative is Travel” Metaphor: Between Spatial Sequence and Open Consequence. Narrative 2007, 15, 286–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, J. The socialities of everyday urban walking and the ‘right to the city’. Urban Stud. 2016, 55, 296–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Dai, Y.; Zan, P.; Zhang, S.; Sun, X.; Zhou, J. Research and Evaluation of the Mountain Settlement Space Based on the Theory of “Flânuer” in the Digital Age—Taking Yangchan Village in Huangshan City, Anhui Province, as an Example. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 23, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppezzo, M.; Schwartz, D.L. Give your ideas some legs: The positive effect of walking on creative thinking. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2014, 40, 1142–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez Miles, A.; Libersat, J.U. ROAM: Walking, Mapping, and Play: Wanderings in Art and Art Education. Stud. Art Educ. 2016, 57, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, R.E. Cartographic Design as Visual Storytelling: Synthesis and Review of Map-Based Narratives, Genres, and Tropes. Cartogr. J. 2020, 58, 83–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumastuti, H.; Pranita, D.; Viendyasari, M.; Rasul, M.S.; Sarjana, S. Leveraging Local Value in a Post-Smart Tourism Village to Encourage Sustainable Tourism. Sustainability 2024, 16, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission (CCaT). 2023 Tourism Industry Statistical Bulletin of Chongqing Municipality. Available online: https://whlyw.cq.gov.cn/sjfb/202404/t20240425_13156888.html (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- China UPSo. Special Plan for Mountain City Trails in Chongqing Main Urban Area. Available online: https://www.planning.org.cn/2016anpc/view?id=666 (accessed on 27 June 2019).

- Azaryahu, M.; Foote, K.E. Historical space as narrative medium: On the configuration of spatial narratives of time at historical sites. GeoJournal 2008, 73, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puxan-Oliva, M. Assessing Narrative Space: From Setting to Narrative Environments. Poet. Today 2024, 45, 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridge, M.; Lafreniere, D.; Nesbit, S. Creating Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives through Design. Int. J. Humanit. Arts Comput. 2013, 7, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalouch, C.; Al-Hajri, S.; Naser, A.; Al Hinai, A. The impact of space syntax spatial attributes on urban land use in Muscat: Implications for urban sustainability. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 46, 101417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Yang, T. Landed and Rooted: A Comparative Study of Traditional Hakka Dwellings (Tulous and Weilong Houses) Based on the Methodology of Space Syntax. Buildings 2023, 13, 2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.; Wang, T.; Zhi, X. Temporal-Spatial pattern Differentiation of Traditional Villages in Central Plains Economic Region. Econ. Geogr. 2017, 37, 225–232. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Feng, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, K. Evaluation of Social Values for Ecosystem Services in Urban Riverfront Space Based on the SolVES Model: A Case Study of the Fenghe River, Xi’an, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mior, F.A. Whose city? Colonial histories, urban governance, and the contestation of space in Kuala Lumpur. Int. Plan. Stud. 2025, 30, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenni, S.; Horlings, L.G.; Soini, K. Linking spatial planning and place branding strategies through cultural narratives in places. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 28, 1355–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S.P.; Carter, P.L.; Potter, A.E.; Bright, C.F.; Alderman, D.A.; Modlin, E.A.; Butler, D.L. Following the story: Narrative mapping as a mobile method for tracking and interrogating spatial narratives. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 14, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschmann, E.E.; Cubbon, E. Sketch Maps and Qualitative GIS: Using Cartographies of Individual Spatial Narratives in Geographic Research. Prof. Geogr. 2013, 66, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caquard, S. Cartography I: Mapping narrative cartography. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2011, 37, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Wen, Y.; Liu, M.; Wu, Y. Industrial Heritage Protection from the Perspective of Spatial Narrative. Land 2025, 14, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, I.; Heath, T. In-between spaces and social interaction: A morphological analysis of Izmir using space syntax. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2015, 31, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China MoCaTotPsRo. 2024 Annual Domestic Tourism Data Report. Available online: https://zwgk.mct.gov.cn/zfxxgkml/tjxx/202501/t20250121_958012.html (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Busselle, R.; Bilandzic, H. Fictionality and Perceived Realism in Experiencing Stories: A Model of Narrative Comprehension and Engagement. Commun. Theory 2008, 18, 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M. Geographical Enrichment of Historical Landscapes: Spatial Integration, Geo-Narrative, Spatial Narrative, and Deep Mapping. In Historical Geography and Geosciences; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Section | Distance | Theme | Description | Main Nodes and Coding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhongshan Fourth Road Section (Section 1) | 1.6 km | Architectural style of the wartime period | Numerous historical features from the period when Chongqing served as the wartime capital have been preserved, reflecting a microcosm of the development of modern education in Chongqing. | Yiyuan (1), Former Residence of Xian Ying (2), Jialingqiao Xicun (3), Daguan Pavilion (4), Niujiaotuo (5), “Through Thick and Thin, Hold Discussions Concerning National Policies and Principles” Sculpture (6), China Democratic League Monument (7), Sanmin Doctrine Association Founding Monument (8), Te Garden (9), Former Site of the Central Executive Committee of KMT (10), Democratic Parties History Museum (11), Chongqingshi Renmin Primary School (12), Zhongshan Creative Park (13), Gui Garden (14), Qiujing Middle School (15), Dejing Primary School (16), Wang Qi Art Museum (17), Residence of Pan Wenhua (19), Residence of Dai Li (20), Enlai Square (21), Former Residence of Zhou Enlai (22), Police Bureau Site (23), Zengjiayan Cultural Hall (24). |

| People’s Assembly Hall Section (Section 2) | 1.4 km | Residences of wartime celebrities and achievements during the Southwest Administrative Region | Centered on the residences of notable figures from the wartime period and the major achievements in the construction of the Southwest Administrative Region. | Former Site of the Executive Yuan of the National Government in Chongqing (18), Residence of Shen Junru (25), Former Site of the Foreign Affairs Section of the Southern Bureau of the CPC Central Committee (26), Ma’anshan Building 29 (27), Ma’anshan Building 30 (28), Ma’anshan Building 31 (29), Ma’anshan Building 63 (30), Ma’anshan Building 64 (31), Ma’anshan Building 47 (32), Renmin Road Building 175 (33), People’s Assembly Hall (34), People’s Square (35), Chongqing China Three Gorges Museum (36). |

| Datianwan Section (Section 3) | 1.2 km | Public cultural activity scenes during the Southwest Administrative Region period | Focused on “recreating the cultural center of Chongqing in the early years of the People’s Republic of China,” with an emphasis on restoring cultural functions and promoting cultural heritage. | Former Site of American Embassy (37), Parachuting Tower (38), Chongqing Sports Museum (39), Datianwan Stadium (40), Chongqing Datianwan Fitness Center (41), Statue of He Long (42), Chongqing Gymnasium (43), Chongqing Municipal Bureau of Sports (44), Former Residence of Soong Ching-ling (45), Former Site of the Eighth Route Army Office—CPC Delegation Office (46), Cultural Palace (47), Former Site of the Investigation and Statistics Bureau of the KMT Central Executive Committee (48). |

| Primary Indicator | Secondary Indicator | Scoring Criteria | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 Points | 4 Points | 3 Points | 2 Points | 1 Point | ||

| Spatial Narrative Resources | Historical Events Count (HE) | ≥5 events | 4 events | 3 events | 2 events | 1 event |

| Narrative Node Importance (NI) | National Key Cultural Relics Protection Unit or National First-grade Museum | Municipal Cultural Relics Protection Unit | District-Level Cultural Relics Protection Unit | General Cultural Relics Site | Historic Building | |

| Narrative Node Chronology (NC) | Ming and Qing Dynasties (Pre–1911) | Republic of China Era (1912–1949) | Post–Liberation Period (1950–1978) | Early Reform and Opening Up Period (1979–1997) | Direct-controlled Municipality Era (Post–1998) | |

| Spatial Narrative Structure | Route Choice (RC) | 0.48–0.59 | 0.37–0.47 | 0.26–0.36 | 0.15–0.25 | 0.04–0.14 |

| Route Integration (RI) | 0.65–0.81 | 0.49–0.64 | 0.32–0.48 | 0.16–0.31 | 0–0.15 | |

| Spatial Narrative Effective-ness | Theme Relevance (TR) | Related | Not related | |||

| Narrative Guidance (NG) 1 | 5 items | 4 items | 3 items | 2 items | 1 item | |

| Thematic Activities Count (TA) | ≥41 times/year | 31–40 times/year | 21–30 times/year | 11–20 times/year | 0–10 times/year | |

| Primary Indicator | Weight | Secondary Indicator | Weight | Final Weight | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Narrative Resources | 46.99% | HE | 37.73% | 17.73% | Open government data and on-site survey statistics Web 1: http://www.cqkaogu.com/gzdt/5903.jhtml (accessed on 27 November 2024) Web 2: http://www.cqkaogu.com/gzdt/5924.jhtml (accessed on 27 November 2024) Web 3: https://www.sohu.com/a/253526033_349058 (accessed on 27 November 2024) |

| NI | 22.34% | 10.50% | Open government data and on-site survey statistics Section 1: https://www.cqyz.gov.cn/zjyz/lyyz/rmdkd/202210/t20221005_11164444.html (accessed on 17 December 2024) Section 2: https://www.cqyz.gov.cn/zjyz/lyyz/ctjq/202210/t20221005_11164464.html (accessed on 18 December 2024) Section 3: https://www.cq.gov.cn/ywdt/jrcq/202212/t20221231_11442662.html (accessed on 17 December 2024) | ||

| NC | 39.94% | 18.77% | Open government data statistics Web 1: https://www.cq.gov.cn/zwgk/zfxxgkml/zdlyxxgk/shgysy/ggwhty/whly/201807/t20180702_8807178.html (accessed on 19 December 2024) Web 2: https://www.cqyz.gov.cn/zwgk_229/zcwj/xzgfxwj/201907/t20190705_6892709.html (accessed on 19 December 2024) Web 3: https://cq.ifeng.com/c/81iNp6zhRwI (accessed on 19 December 2024) | ||

| Spatial Narrative Structure | 22.71% | RC | 48.91% | 11.11% | Space syntax-based analytical data |

| RI | 51.09% | 11.60% | Space syntax-based analytical data | ||

| Spatial Narrative Effectiveness | 30.30% | TR | 40.55% | 12.29% | On-site survey statistics |

| NG | 42.53% | 12.88% | On-site survey statistics | ||

| TA | 16.92% | 5.13% | On-site survey statistics |

| Primary Indicator | Secondary Indicator | Definition | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Narrative Resources | Narrative Symbol Richness (SR) | The diversity of narrative symbols displayed within the trail environment. | Questionnaire Survey |

| Narrative Resource Visibility (RV) | The extent to which the trail’s narrative resources excavate and manifest the local historical and cultural context. | ||

| Narrative Resource Prominence (RP) | The degree of prominence of the narrative resources of the trail. | ||

| Spatial Narrative Structure | Narrative Logic Clarity (LC) | The extent to which the storyline embedded in the space is logically structured and easy for visitors to comprehend. | |

| Narrative Thread Identifiability (TI) | The ease with which visitors can recognize and follow the main narrative thread throughout the trail. | ||

| Narrative Route Selectivity (RS) | The degree to which visitors can seamlessly navigate and choose between narrative paths and nodes. | ||

| Spatial Narrative Continuity (SC) | The convenience and fluidity of pedestrian movement, indicating uninterrupted narrative progression in space. | ||

| Narrative Structural Situationality (NS) | The degree to which the storyline associated with the narrative structure is contextually embedded within the space. | ||

| Spatial Narrative Effectiveness | Emotional Resonance Intensity (ER) | The strength of emotional engagement elicited by the narrative elements along the trail. | |

| Cultural Educational Value (CE) | The amount and significance of new cultural or historical knowledge acquired by visitors. | ||

| Interaction Diversity (ID) | The variety and richness of interactive opportunities along the trail. | ||

| Cultural Identity (CI) | The extent of visitors’ recognition of the specific historical events presented. | ||

| Primary Factor | Overall Experience Evaluation (OE) | Visitors’ overall satisfaction with their trail experience. |

| No. | Value | Trail | Section 1 | Section 2 | Section 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Average | 0.311 | 0.341 | 0.312 | 0.274 |

| 2 | Minimum | 0.043 | 0.083 | 0.094 | 0.043 |

| 3 | Maximum | 0.586 | 0.496 | 0.496 | 0.586 |

| 4 | Std Dev | 0.091 | 0.070 | 0.085 | 0.107 |

| No. | Value | Trail | Section 1 | Section 2 | Section 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Average | 0.572 | 0.552 | 0.577 | 0.589 |

| 2 | Minimum | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | Maximum | 0.811 | 0.699 | 0.728 | 0.811 |

| 4 | Std Dev | 0.093 | 0.092 | 0.079 | 0.112 |

| Dimensions | Section | Negligible (%) | Low (%) | Medium (%) | High (%) | Very High (%) | Narrative-Value Potential Zones (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Narrative Resources | Section 1 | 51.71 | 31.48 | 16.81 | - | - | 16.81 |

| Section 2 | 75.91 | 6.48 | 7.77 | 3.99 | 5.85 | 17.61 | |

| Section 3 | 77.44 | 11.17 | 11.39 | - | - | 11.39 | |

| Spatial Narrative Structure | Section 1 | 25.80 | 53.69 | 7.58 | 12.85 | 0.08 | 20.51 |

| Section 2 | 7.90 | 25.81 | 13.64 | 40.47 | 12.19 | 66.30 | |

| Section 3 | 18.72 | 42.88 | 15.23 | 14.39 | 8.78 | 38.40 | |

| Spatial Narrative Effectiveness | Section 1 | 40.05 | 27.32 | 21.42 | 6.81 | 4.42 | 32.65 |

| Section 2 | 62.22 | 17.96 | 8.18 | 6.06 | 5.58 | 19.82 | |

| Section 3 | 54.68 | 37.51 | 7.81 | - | - | 7.81 | |

| Overall | Section 1 | 48.65 | 29.81 | 17.08 | 4.45 | - | 21.53 |

| Section 2 | 61.37 | 19.00 | 8.29 | 4.87 | 6.46 | 19.62 | |

| Section 3 | 67.75 | 19.61 | 11.40 | 1.24 | - | 12.64 |

| Variable | Category (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | Female | |||

| 44.51 | 55.49 | ||||

| Education | Bachelor’s Degree | Master’s Degree or Above | College Degree | High School or Below | |

| 33.53 | 31.79 | 22.54 | 12.14 | ||

| Age Group | 18–25 years old | 26–35 years old | 36–45 years old | 46–59 years old | 60 years old and above |

| 38.15 | 19.65 | 19.08 | 16.18 | 6.94 | |

| Indicator | Mean Score | ANOVA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Section 1 | Section 2 | Section 3 | Total | F | Sig. (p) | |

| TI | 3.26 | 2.84 | 2.65 | 2.93 | 6.590 | 0.002 * |

| SC | 3.57 | 3.43 | 3.21 | 3.42 | 2.500 | 0.083 |

| ID | 3.17 | 2.98 | 2.67 | 2.96 | 4.317 | 0.014 * |

| Model 1: Spatial Narrative Resources | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. (p) | Collinearity Statistics | |||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 0.829 | 0.196 | 4.224 | 0.000 | |||

| SR | 0.383 | 0.056 | 0.343 | 6.842 | 0.000 | 0.665 | 1.505 | |

| RP | 0.251 | 0.048 | 0.254 | 5.231 | 0.000 | 0.711 | 1.407 | |

| RV | 0.141 | 0.048 | 0.147 | 2.943 | 0.003 | 0.668 | 1.498 | |

| Model 2: Spatial Narrative Structure | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. (p) | Collinearity Statistics | |||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 0.807 | 0.186 | 4.334 | 0.000 | |||

| RS | 0.272 | 0.048 | 0.282 | 5.615 | 0.000 | 0.611 | 1.637 | |

| SC | 0.214 | 0.045 | 0.224 | 4.797 | 0.000 | 0.707 | 1.414 | |

| LC | 0.178 | 0.049 | 0.182 | 3.613 | 0.000 | 0.605 | 1.654 | |

| NS | 0.147 | 0.047 | 0.149 | 3.113 | 0.002 | 0.667 | 1.499 | |

| TI | 0.008 | 0.036 | 0.009 | 0.215 | 0.830 | 0.902 | 1.109 | |

| Model 3: Spatial Narrative Effectiveness | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. (p) | Collinearity Statistics | |||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 0.808 | 0.185 | 4.377 | 0.000 | |||

| CE | 0.295 | 0.047 | 0.309 | 6.248 | 0.000 | 0.639 | 1.565 | |

| CI | 0.273 | 0.047 | 0.273 | 5.764 | 0.000 | 0.696 | 1.438 | |

| ER | 0.190 | 0.047 | 0.189 | 4.017 | 0.000 | 0.704 | 1.420 | |

| ID | 0.047 | 0.038 | 0.052 | 1.221 | 0.223 | 0.851 | 1.175 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Meng, F. Evaluation of the Narrative Value and Experiential Quality of Urban Trails: A Case Study of the Southwest Regional Trail in Chongqing, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5544. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125544

Wang Z, Liu Y, Yang L, Meng F. Evaluation of the Narrative Value and Experiential Quality of Urban Trails: A Case Study of the Southwest Regional Trail in Chongqing, China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5544. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125544

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhongde, Yuhan Liu, Ling Yang, and Fanwei Meng. 2025. "Evaluation of the Narrative Value and Experiential Quality of Urban Trails: A Case Study of the Southwest Regional Trail in Chongqing, China" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5544. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125544

APA StyleWang, Z., Liu, Y., Yang, L., & Meng, F. (2025). Evaluation of the Narrative Value and Experiential Quality of Urban Trails: A Case Study of the Southwest Regional Trail in Chongqing, China. Sustainability, 17(12), 5544. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125544