Abstract

This study examines how Chinese tourists perceive the value of sustainable practices implemented in five-star hotels in Phuket, Thailand, through the lens of the perceived value theory and the service experience framework. While luxury hotels increasingly adopt green initiatives, research exploring how tourists evaluate these efforts across the full guest journey is limited. Addressing this gap, this study aimed to examine how attitudinally distinct tourist segments perceive sustainable practices across three service stages: pre-consumption, consumption, and post-consumption. A cross-sectional survey of 400 Chinese tourists was conducted, applying k-means clustering to segment respondents by sustainability attitudes, followed by multi-group structural equation modeling. Two segments emerged: environmentally engaged travelers and conventional comfort travelers. The results indicate that the emotional value dominates during the stay, the functional value drives pre-stay decisions, and the ethical/social value shapes post-stay reflections. Environmentally engaged tourists were more responsive to ethical and social cues. The findings highlight sustainability as a multidimensional, stage-specific construct moderated by guest attitudes. Theoretically, this research extends perceived value frameworks by mapping sustainability perceptions across the guest journey. Practically, it offers actionable insights for hotel managers seeking to design value-aligned green strategies and segmented communication. Tailoring sustainability initiatives to tourist profiles can enhance satisfaction, loyalty, and advocacy in the luxury hospitality sector.

1. Introduction

The tourism and hospitality industry is experiencing a fundamental shift as sustainability emerges as a central pillar of innovation, competitiveness, and long-term viability. Amid growing concerns about climate change, resource depletion, and social equity, both policymakers and consumers are increasingly demanding responsible tourism practices that minimize environmental harm and foster inclusive development [1]. Within this broader context, the hotel sector plays a pivotal role due to its intensive resource use and close interface with tourists’ daily experiences. Sustainable hotel operations now encompass a broad range of practices, including energy and water efficiency, ethical supply chains, digital innovations, and local community engagement [2,3,4].

Despite these advancements, a persistent challenge remains: understanding how guests, especially those from diverse cultural backgrounds, perceive the value of such sustainability efforts. While many hospitality firms have made substantial progress in implementing green initiatives, there remains a critical gap in how these efforts are evaluated by guests with differing levels of environmental awareness [5,6]. As travelers increasingly seek personalized and meaningful experiences, the success of sustainability initiatives hinges not only on their presence but also on their perceived relevance and value to different customer segments [7].

Furthermore, emerging research suggests that perceptions of sustainability are increasingly linked to broader concerns about health, safety, and personal well-being [8,9]. In the context of luxury hospitality, tourists often associate sustainable practices with reduced risks, enhanced wellness, and a greater sense of quality of life, factors that have become even more salient in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Konstantakopoulou (2022) demonstrated that perceived health risks significantly influenced Chinese tourists’ intentions to stay in luxury hotels, reinforcing the need to consider well-being as part of the sustainable value proposition [10]. These findings highlight that sustainability is not only an environmental issue but also a lifestyle and health-related concern, especially among high-end travel segments.

Growing evidence suggests that sustainable practices are only effective when perceived as personally valuable and aligned with guests’ expectations at different moments of their travel experience [11]. As such, exploring how perceived value manifests across the full-service journey, rather than at a single point in time, can yield richer insights into sustainable guest engagement. This issue is particularly salient in the context of five-star hotels, where sustainability efforts are often more advanced and symbolically significant. In luxury hospitality, sustainable practices are not only operational choices but also serve as markers of brand identity and customer engagement. Yet, the perceived value of these initiatives, from functional benefits such as convenience or efficiency to emotional, ethical, and social meanings, has not been thoroughly explored [12,13]. Previous research has primarily focused on service quality or satisfaction in upscale settings [14], leaving a gap in how luxury guests evaluate green initiatives across the holistic guest journey.

As the discussion on sustainable value becomes more nuanced, it is essential to situate such inquiry within destinations that face both intense tourism pressure and evolving sustainability agendas. Phuket, Thailand, serves as a strategic and contextually rich setting for this research. As one of Asia’s most prominent resort destinations, Phuket embodies the tensions between mass tourism development and sustainability imperatives [15]. It has become a focal point for Thailand’s national push toward green tourism, with increasing investment in sustainable infrastructure and hospitality standards [1]. Five-star hotels in Phuket are not only prominent actors in this transition but also symbolic arenas where sustainability is performed and evaluated by international tourists. These properties often target environmentally conscious travelers yet face the challenge of catering to guests with diverse values and awareness levels, making them ideal for investigating differentiated perceptions of sustainable value [11].

The focus on Chinese outbound tourists is both timely and theoretically important. China remains the largest source of international travelers globally, and Thailand, especially Phuket, has consistently ranked among the top destinations [16]. However, Chinese tourists are far from homogeneous. Recent studies highlight growing variability in their sustainability attitudes, with segments ranging from environmentally committed travelers to those indifferent or skeptical about green claims [17,18,19]. These attitudinal differences influence how sustainability initiatives are interpreted and valued in hotel settings, thus necessitating segmentation approaches that go beyond demographic profiling [20].

To address these theoretical and practical gaps, this study adopts an attitudinal segmentation approach to classify Chinese tourists staying in five-star hotels in Phuket according to their sustainability orientation. Using k-means clustering, two distinct groups are identified and compared through multi-group structural equation modeling (SEM) to evaluate how they perceive sustainable hotel practices across different service stages. This research aimed to (1) classify Chinese tourists based on sustainability attitudes; (2) identify value perceptions linked to sustainable practices at each service stage; and (3) examine attitudinal differences in value assessment. By combining stage-based value theory with attitudinal segmentation, this study advances the literature on sustainable tourism and provides actionable insights for luxury hotel managers seeking to align green strategies with diverse guest expectations.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Chinese Outbound Tourism and Evolving Consumer Profiles

China has remained the world’s largest outbound tourism market for over a decade, with Chinese travelers playing an increasingly influential role in shaping global tourism trends [1]. In 2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately 155 million Chinese tourists traveled abroad. Thailand consistently ranked among the top destinations, due to its geographic proximity, affordability, cultural familiarity, and relaxed visa policies [15,19]. As the global tourism sector recovers, forecasts project a robust rebound in Chinese outbound travel, fueled by pent-up demand, economic recovery, and the easing of travel restrictions [21,22].

Notably, the profile of the Chinese outbound tourist has undergone a significant transformation. Earlier, outbound tourists were often part of group tours, with a strong emphasis on sightseeing and shopping. In contrast, contemporary travelers exhibit greater diversity in income, travel frequency, and expectations around personalization and quality [23]. Millennials and Gen Z travelers are now central to this market, bringing with them higher levels of digital literacy, a preference for independent and experience-driven travel, and an increasing awareness of ethical and sustainable consumption [24,25].

This evolution has significant implications for tourism-dependent destinations. Given this shift in traveler characteristics, destinations such as Phuket, Thailand, long popular with Chinese tourists, must adapt to accommodate these emerging preferences among Chinese travelers, from affluent leisure seekers to environmentally conscious youth and middle-income families. While Tier 1 cities such as Beijing and Shanghai remain major source markets, outbound tourism is now also driven by travelers from lower-tier cities, empowered by rising disposable income and improved travel infrastructure [17,26].

As the Chinese outbound tourist market becomes increasingly diverse, traditional segmentation approaches based solely on demographics, such as age, income, or city of origin, are proving insufficient for capturing the complexity of traveler motivations. In response, scholars now advocate for attitudinal and psychographic segmentation, which considers tourists’ values, lifestyles, and behavioral tendencies, offering deeper insights into their preferences and decision-making processes [25]. Attributes such as environmental values, sustainability preferences, and lifestyle choices are increasingly shaping consumer behavior. Notably, while many Chinese tourists express positive attitudes toward sustainable tourism, these attitudes do not always translate into a willingness to pay for sustainable services, especially when skepticism is present [27].

Understanding the evolving profile of Chinese outbound tourists, particularly their growing heterogeneity and nuanced attitudes toward sustainability, is critical for hotel operators seeking to implement impactful green practices. By tailoring sustainable initiatives to align with the values of diverse traveler segments, hospitality providers can not only enhance guest satisfaction but also contribute meaningfully to global sustainable tourism goals [28]. Addressing this evolving landscape, the present study explores how different Chinese tourist segments perceive sustainable hotel practices in Phuket, providing nuanced insights to inform strategic service design.

2.2. Attitudes Toward Sustainability in Tourism

Attitudes toward sustainability in tourism reflect an individual’s cognitive, emotional, and behavioral orientation toward practices that minimize environmental harm, promote social equity, and support the long-term viability of the tourism industry [29]. In travel and hospitality contexts, such attitudes influence a wide range of decisions, including destination selection, accommodation preferences, modes of transportation, and the willingness to engage with green services [30]. As climate change and environmental degradation receive growing global attention, sustainability attitudes are playing an increasingly influential role in shaping tourist behavior, particularly among younger, urban, and educated travelers [17,31]. Empirical evidence supports these trends. For example, Han et al. (2017) demonstrated that age and gender moderate how the value–belief–norm (VBN) model predicts pro-environmental behavior, with younger individuals more likely to align their sustainable attitudes with actual behaviors [32]. These findings underscore the importance of understanding sustainability attitudes as a key determinant of environmentally responsible behavior in tourism.

The formation of pro-sustainability attitudes is frequently analyzed using frameworks such as the VBN theory, which posits that biospheric values foster beliefs about environmental consequences and personal responsibility, ultimately guiding pro-environmental action [33]. In tourism, this model helps explain why some travelers actively seek eco-labeled accommodations and low-impact experiences, while others remain disengaged despite being informed [18,34]. However, attitudes alone do not always translate into action. Factors such as green skepticism, perceived inconvenience, prevailing social norms, and distrust in sustainability claims significantly mediate the intention–behavior relationship [35]. This attitude–behavior gap remains a persistent theme in sustainability research. Higham et al. (2016), for instance, highlighted how tourists may express environmental concern yet continue high-emission travel behaviors such as frequent flying [36]. Other studies similarly note that contextual barriers, such as price sensitivity or limited availability of sustainable alternatives, often prevent tourists from acting on their stated values [37,38].

Understanding these dynamics within specific national contexts is essential. In China, where economic development has historically taken precedence over environmental considerations, pro-sustainability attitudes have only recently emerged as a significant cultural force. However, a shift is becoming evident, particularly among youth from Tier 1 cities, who increasingly express environmental concern and demonstrate a greater willingness to pay for eco-friendly hospitality services [23]. Nonetheless, the gap between sustainability attitudes and actual behaviors remains pronounced. This discrepancy is often attributed to barriers such as cost, limited accessibility of sustainable options, and cultural preferences emphasizing comfort and social status [31,34]. Moreover, Berezan et al. (2013) found that guest responses to sustainable hotel practices vary by nationality, influencing satisfaction and brand loyalty and reinforcing the importance of tailoring sustainability strategies to specific cultural markets [39].

Tourists’ sustainability attitudes are far from uniform. They vary significantly based on age, region, income, education, and prior exposure to nature or sustainability education [40,41,42]. Recent empirical reviews have affirmed that attitudinal and psychographic segmentation, especially when based on environmental concern, remains a robust tool for predicting sustainable behavior across diverse tourism contexts. This heterogeneity reinforces the value of attitudinal segmentation in hospitality research. By identifying distinct subgroups, such as “strong sustainers” with high environmental commitment versus “neutral sustainers” with moderate concern, hotels and tourism providers can design more targeted and persuasive sustainability strategies [12,43].

Moreover, positive sustainability attitudes are strongly associated with favorable hotel evaluations, increased brand trust, and stronger guest loyalty. Environmentally conscious tourists are more responsive to transparency in the pre-booking phase, expect resource-efficient practices during their stay, and appreciate responsible communication after departure [44,45]. Integrating sustainability attitudes into service design and customer segmentation is, therefore, not only conceptually sound but also strategically imperative for hospitality providers aiming to achieve long-term competitiveness and contribute to global sustainability goals.

2.3. Sustainable Hotel Practices Across the Service Journey

Understanding guest experience in the hospitality industry requires a structured and theoretically informed perspective on how service interactions unfold across time and touchpoints. The hotel guest service journey framework, adapted from broader models of customer experience, captures the sequential phases through which guests engage with hotel services: pre-consumption, consumption, and post-consumption [46]. This journey-based lens is well-aligned with the principles of service-dominant logic, which emphasize that value is not embedded in service outputs but is co-created through interaction, interpretation, and experience [47]. Within this framework, each stage offers unique opportunities to embed sustainability meaningfully, shape perceived value, and strengthen brand differentiation through responsible service design [48,49]. Each stage offers distinct entry points for embedding sustainable practices. The following subsections explore how sustainability can be operationalized at each stage of the hotel service journey.

2.3.1. Sustainable Hotel Practices in the Pre-Consumption Stage

The pre-consumption stage involves the anticipatory phase of the hotel service journey, including information search, hotel evaluation, and booking decisions. From a theoretical perspective, this stage plays a critical role in shaping expectations and constructing the initial mental model of the guest experience [50]. Within the framework of the signaling theory, sustainability-related content, such as green certifications, ecolabels, or explicit sustainability messaging, acts as a signal of quality, ethical commitment, and brand integrity which consumers interpret as proxies for otherwise unobservable service attributes [51]. These signals shape early impressions and significantly affect perceived value and brand trust, particularly among environmentally conscious consumers [17].

In hospitality contexts, where the perceived risk is high due to service intangibility, these signals are even more critical. Digital platforms serve as the primary interface for value co-creation in this phase. Hotels increasingly use interactive content, virtual tours, and green storytelling to showcase their sustainability credentials, such as low-carbon amenities, waste reduction practices, and community engagement efforts [52]. Furthermore, carbon calculators, environmental impact scores, and transparent reporting dashboards enable guests to evaluate eco-performance as part of their decision-making [53]. These tools do not merely inform; they actively shape functional and ethical value perceptions, reinforcing the hotel’s brand positioning before physical service delivery begins.

The role of third-party platforms such as online travel agencies (OTAs) and meta-search engines has also evolved to facilitate value co-creation. With sustainability filters and verified ecolabels now embedded in the user interface, eco-certified hotels can more effectively reach the growing segment of values-driven travelers [54]. Clear, credible, and emotionally resonant communication during this stage has been shown to increase not only booking intent but also perceived authenticity and relationship quality [48]. As Prebensen and Rosengren (2016) argue, the perceived value begins well before the actual service encounter, and thus the pre-consumption stage represents a vital arena for hospitality providers to communicate purpose, differentiate ethically, and cultivate long-term guest engagement [55].

2.3.2. Sustainable Hotel Practices in the Consumption Stage

The consumption stage refers to the actual stay experience, encompassing check-in, room quality, service delivery, dining, amenities, and on-site interactions with staff. This phase is critical in the value co-creation process, as guests interact with the service environment and directly evaluate whether the hotel’s sustainability promises are fulfilled [56]. Drawing on the perspective of service-dominant logic, value at this stage is not passively received but is co-created through the integration of guest resources, environmental cues, and interpersonal interactions. As tourists increasingly seek immersive and meaningful experiences, the consumption stage becomes pivotal for reinforcing sustainability-driven value propositions [12].

Recent studies have emphasized that green building design, biophilic elements, and ergonomic interiors not only reduce environmental impact, but also enhance guest well-being and satisfaction [57]. Operational features such as keycard-controlled lighting, dual-flush toilets, and refillable dispensers align resource efficiency with guest comfort. These physical elements contribute significantly to functional value while simultaneously shaping guest perceptions of ethical commitment and environmental responsibility [58]. Additionally, infrastructure–practice dynamics, which refer to how built environments shape and are shaped by guest behavior, play a significant role in determining the success of in-stay sustainability efforts [59]. For example, design elements that nudge guests toward sustainable choices, such as clearly labeled recycling bins or refillable toiletries, help reinforce environmentally conscious behavior without compromising comfort.

Staff engagement is also vital during this stage. Trained personnel who can communicate sustainability practices and encourage guest participation, such as linen reuse programs, energy-saving behaviors, or composting bins, not only operationalize hotel sustainability, but also enhance perceived authenticity and guest buy-in [60]. These human touchpoints foster emotional and ethical value, as guests feel that their behaviors align with broader sustainability goals [61,62]. By embedding sustainability seamlessly into service delivery, hotels not only reduce operational costs, but also increase perceived service quality and brand loyalty [63].

Furthermore, emotional experiences during the stay significantly influence guests’ overall image of the hotel, satisfaction levels, and their intention to recommend the property to others [64]. The ability of a hotel to deliver a stay that is not just comfortable but also emotionally and ethically resonant is increasingly central to guest satisfaction. As such, the consumption stage is more than a moment of service delivery; it is a strategic opportunity to co-create perceived value through meaningful sustainability engagement, both tangible and experiential.

2.3.3. Sustainable Hotel Practices in the Post-Consumption Stage

The post-consumption stage refers to the period following guest checkout, encompassing feedback solicitation, online reviews, loyalty engagement, and long-term brand interaction. From a theoretical perspective, this stage is vital for reinforcing the perceived value, cultivating brand loyalty, and sustaining the co-creation of meaning and identity beyond the physical service encounter [13]. Particularly in sustainability-oriented hospitality contexts, post-stay interactions serve to validate the authenticity of the hotel’s environmental commitments, shaping guest memory and future behavioral intentions [65].

Hotels are increasingly leveraging post-stay touchpoints to communicate guests’ individual environmental contributions during their stay. For example, automated messages or reports showing the amount of water or energy saved due to behaviors such as reduced daily linen changes or opting for digital receipts help guests visualize their role in sustainability outcomes [66]. These forms of personalized sustainability feedback not only reinforce guests’ previous actions, but also encourage future booking intent, positive affect, and social sharing [52,67]. Such strategies also align with findings in relationship marketing, which emphasize the importance of after-service communication in fostering emotional bonds and advocacy behavior.

In parallel, sustainability-linked loyalty programs are emerging as effective mechanisms to extend the sustainability narrative beyond the stay. These programs reward guests for green actions, such as reusing towels, choosing low-emission transportation, or supporting local vendors, thus embedding sustainability into the guest’s ongoing relationship with the brand [68]. Furthermore, user-generated content in the form of online reviews and ratings that mention environmental practices amplifies the hotel’s green positioning and builds peer-based social validation [69,70].

However, the credibility of post-stay engagement depends on consistency between pre-visit promises, in-stay delivery, and post-stay communication. Discrepancies between communicated values and actual guest experiences can undermine trust, especially among environmentally aware travelers, and lead to perceptions of greenwashing [66]. Therefore, authenticity, transparency, and alignment across all touchpoints are essential for reinforcing value, maintaining brand integrity, and building a base of environmentally aligned brand advocates [71]. The post-consumption stage thus completes the service journey loop, offering a critical opportunity for hotels to transform sustainable experiences into long-term loyalty and advocacy.

2.4. Perceived Value in Sustainable Hospitality

Perceived value in hospitality refers to the guest’s overall assessment of the utility, benefits, and worth derived from a service relative to the costs [72]. While this conceptualization remains foundational, recent studies have increasingly emphasized that perceived value is a multidimensional, context-dependent, and experience-based construct, particularly in sustainable hospitality settings [19,42]. As sustainability becomes central to hotel strategy and brand positioning, a more comprehensive understanding of how guests interpret and derive value from sustainable practices is critical for enhancing competitive advantage, fostering loyalty, and guiding responsible service [55]. In this domain, value expands beyond traditional functional and economic dimensions to include emotional, environmental, social, and ethical considerations, reflecting tourists’ growing concern for responsible consumption and impact-aware travel behaviors [12].

In this domain, perceived value extends beyond traditional economic and utilitarian concerns to encompass four dimensions: functional, emotional, social, and ethical/environmental value [72,73,74]. Functional value pertains to tangible benefits such as comfort, efficiency, or convenience, for instance, energy-saving systems or efficient check-in technologies. Emotional value arises from affective states such as pride, joy, or moral satisfaction derived from supporting eco-friendly practices. Social value relates to recognition or conformity within peer networks, where staying at green-certified properties signals status or shared values. Ethical/environmental value refers to the moral gratification guests experience when their consumption aligns with broader environmental or social good. This four-dimensional framework is both representative of contemporary hospitality literature and validated across multiple empirical studies, offering a robust structure for understanding sustainable guest experiences [58,75].

In addition to its multidimensionality, perceived value is inherently temporal and shaped by service stage progression. Unlike static conceptualizations that assess value at a single point in time, recent perspectives have emphasized that value is dynamically constructed throughout the guest journey, from pre-arrival interactions to post-departure reflections [46]. In the pre-consumption stage, value may stem from digital transparency, sustainability labeling, and green booking platforms that build initial trust and shape expectations [76]. During the consumption stage, physical and experiential features, such as biophilic design, sustainable food options, and staff engagement, directly contribute to value realization [77]. In the post-consumption stage, follow-up communication, personalized sustainability impact reports, and loyalty programs tied to green behavior help reinforce value and shape future behavioral intentions [13,52].

This temporally and contextually grounded approach to perceived value offers theoretical completeness by accounting for how different value dimensions emerge and shift across the guest journey. It also aligns with the broader service-dominant logic in hospitality, wherein value is co-created through interaction and interpretation rather than being solely embedded in the service offering [47,78,79]. Importantly, value perceptions are not uniform across all guests. Attitudinal segmentation research has shown that “strong sustainers” are more likely to recognize and prioritize ethical and emotional value, while more pragmatic guests may focus on functional or economic aspects [80]. Furthermore, perceived authenticity and trust remain essential mediators. Green skepticism, particularly in luxury hospitality, can diminish the perceived value of sustainability efforts if guests suspect superficiality or inconsistency between claims and actual performance [20].

By synthesizing these theoretical insights, this study positions perceived value as a comprehensive, representative, and operationally useful framework for evaluating sustainable hotel practices. Through the integration of multidimensional value constructs with a stage-specific service experience perspective, the model addresses both conceptual clarity and real-world applicability. This approach provides a meaningful foundation for subsequent empirical analysis and supports the design of segmented sustainability strategies that resonate with diverse tourist expectations.

2.5. Development Hypotheses and Conceptual Research Framework

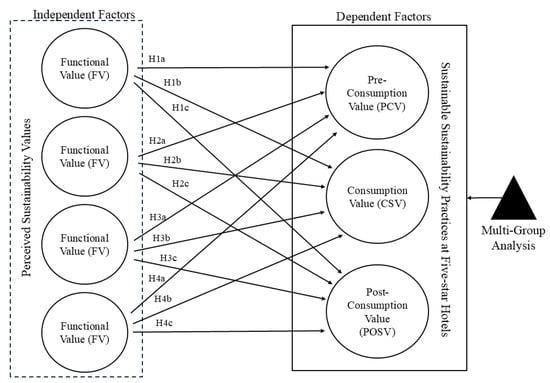

To explore whether tourists with different sustainability attitudes evaluate sustainable practices differently, this study also includes a multi-group analysis. Respondents are segmented into two clusters using k-means clustering based on their sustainability attitudes. It is hypothesized that the strength of the relationships between the perceived value dimensions and the guest journey stages differs significantly between high and low sustainability perception groups, as travelers with stronger environmental values are more likely to respond positively to sustainable practices across all stages.

In the pre-consumption stage, tourists are exposed to sustainability cues while researching, evaluating, and booking accommodations. Functional value, such as clarity of green certifications or intuitive booking processes, can improve decision-making confidence. Emotional value may be triggered by anticipation, trust, or identification with a sustainable brand. Ethical/environmental value influences tourists’ intention to support eco-conscious hotels, while social value may emerge from wanting to align with socially responsible peers. Therefore, it is hypothesized that all four value dimensions positively influence perceived value during the pre-consumption stage.

During the consumption stage, guests interact directly with hotel services. Functional value arises through the practicality and performance of green amenities (e.g., low-energy rooms, sustainable materials). Emotional value emerges through feelings of comfort, satisfaction, or pride. Social value can be experienced when travelers perceive recognition or alignment with like-minded guests. Ethical/environmental value continues to influence satisfaction through guests’ observation of visible environmental and social practices. Hence, it is hypothesized that each value dimension positively impacts perceived value during the consumption stage.

In the post-consumption stage, guests reflect on their experience and may engage in loyalty behaviors or share their opinions with others. Functional value may influence post-stay satisfaction through convenience and ease of digital communication. Emotional value contributes to feelings of pride or fulfillment that persist after the stay. Social value may be expressed through public reviews or recommendations. Ethical/environmental value becomes salient when guests believe their choice contributed to a positive impact. As such, all four value dimensions were hypothesized to influence the post-consumption value.

Based on the arguments above, the following twelve hypotheses were proposed:

- H1a: Functional value positively influences perceived value at the pre-consumption stage.

- H1b: Functional value positively influences perceived value at the consumption stage.

- H1c: Functional value positively influences perceived value at the post-consumption stage.

- H2a: Emotional value positively influences perceived value at the pre-consumption stage.

- H2b: Emotional value positively influences perceived value at the consumption stage.

- H2c: Emotional value positively influences perceived value at the post-consumption stage.

- H3a: Social value positively influences perceived value at the pre-consumption stage.

- H3b: Social value positively influences perceived value at the consumption stage.

- H3c: Social value positively influences perceived value at the post-consumption stage.

- H4a: Ethical/environmental value positively influences perceived value at the pre-consumption stage.

- H4b: Ethical/environmental value positively influences perceived value at the consumption stage.

- H4c: Ethical/environmental value positively influences perceived value at the post-consumption stage.

The proposed conceptual framework is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework—perceived value dimensions and guest service journey stages. Source: created by the authors (2025).

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This study adopts a quantitative, cross-sectional research design to explore how Chinese tourists perceive the value of sustainable hotel practices across various stages of the hotel service journey. A segmentation-based approach is employed, using k-means clustering to classify tourists according to their attitudes toward sustainability, an approach that has gained traction in tourism studies for its ability to reveal meaningful behavioral clusters [81,82]. Subsequent multi-group analysis is conducted to examine how each cluster evaluates sustainable practices during the pre-consumption, consumption, and post-consumption stages. This design supports statistical rigor and enhances generalizability across wider populations, especially within tourism studies involving perceptual constructs [83,84].

3.2. Population and Sampling

The target population includes Chinese tourists who visited Phuket, Thailand, and stayed specifically in five-star hotels between 2022 and 2023. In this study, the term “Chinese tourists” refers exclusively to nationals of Mainland China. Respondents from Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan were not included in order to ensure cultural, political, and travel policy consistency within the sample. These regions differ significantly in terms of visa regulations, media exposure, and sustainability discourse, which may influence tourist perceptions and behaviors in ways not representative of Mainland Chinese travelers. This group was selected due to China’s continued status as a leading outbound tourism market and the Thai government’s strategic emphasis on high-value and sustainable tourism [85]. A purposive non-probability sampling technique was employed to ensure that respondents were relevant to the research objectives. Participants were required to (1) be Chinese nationals, (2) have stayed in Phuket hotels, and (3) have reported exposure to sustainability-related hotel practices during their trip. This sampling strategy aligns with previous segmentation studies in sustainability-focused tourism, where participant relevance outweighed representativeness for exploratory clustering purposes [86].

To ensure adequate statistical power for clustering and multi-group analysis, the sample size was guided by Krejcie and Morgan’s (1970) formula [87]. A target of at least 400 valid responses was set, consistent with thresholds found effective in prior segmentation research using similar analytical tools [88]. Data were collected both online and on-site to enhance diversity of responses, with the survey offered in Mandarin and English to accommodate linguistic variation.

3.3. Research Instrument and Measurement

The research instrument was a structured questionnaire comprising three main components: demographics, sustainability attitudes, and perceived value of sustainable hotel practices. The demographic section included age, gender, income, education, city of residence, and international travel frequency. Sustainability attitudes were measured through a validated Likert scale (from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree), adapted from Han et al. (2023), capturing constructs such as environmental concern, personal accountability, and eco-consciousness in travel [17].

Perceived value was assessed across three service journey stages, pre-consumption, consumption, and post-consumption, using multidimensional scales adapted from Teng et al. (2023) and Chang et al. (2024) [44,89]. These dimensions include functional (e.g., efficiency, convenience), emotional (e.g., well-being, satisfaction), social (e.g., social approval, recognition), and ethical (e.g., moral fulfillment) value. The questionnaire was pretested with 30 Chinese travelers to refine item clarity and ensure cultural sensitivity. Adjustments were made based on pilot feedback, following standard pretesting practices in tourism instrument design [90].

3.4. Data Analysis Procedures

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 26 and AMOS 28 software. The process began with descriptive statistics to summarize demographic profiles and response patterns. Internal consistency and construct validity were evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha (α ≥ 0.70) and exploratory factor analysis (EFA), respectively. K-means clustering was employed to group respondents by sustainability attitude, with the optimal number of clusters determined via the elbow method and the silhouette coefficient—both widely accepted in tourism segmentation research [81,82]. To ensure the stability and robustness of the cluster solution, a split-half replication procedure was applied. The dataset was randomly divided into two equal halves, and clustering was performed independently on each subset. The resulting clusters showed consistent patterns in centroid positions and attitudinal profiles, supporting the replicability of the segmentation structure. Additionally, multiple random initializations (k-means++ with 10 iterations) were used to minimize sensitivity to starting points and avoid local minima.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to validate the measurement model for perceived value dimensions across the service journey. Multi-group analysis (e.g., independent sample t-tests or MANOVA) then investigated how these segments differed in their evaluations of sustainable hotel practices across the different service stages. This combination of analytical techniques provides a rigorous framework for hypothesis testing and has been successfully applied in recent sustainability-focused segmentation studies [84].

3.5. Ethical Considerations

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the author’s institutional review board. All the participants were fully informed about the study’s objectives and procedures. Informed consent was obtained prior to participation, and the respondents were assured of their anonymity and the confidentiality of their responses. Data were securely stored and used exclusively for academic purposes. These ethical safeguards are consistent with the best practices in sustainable tourism research [91].

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Respondents

A total of 400 valid responses were collected from Chinese tourists who had stayed in five-star hotels in Phuket, Thailand. Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents, including gender, age, education, income, travel frequency, and type of city of residence. The sample reflected diversity in travel behaviors and sustainability awareness levels, essential for robust segmentation analysis.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents.

4.2. K-Means Cluster Analysis: Attitudinal Segmentation

To segment Chinese tourists based on their sustainability attitudes, k-means clustering was employed. This unsupervised learning technique is widely recognized in tourism research for its ability to identify distinct market segments based on multidimensional psychographic and attitudinal data. After testing multiple cluster solutions ranging from two to five groups, the optimal number of clusters was determined to be two, using both the elbow method and silhouette coefficient analysis to validate clustering quality (Table 2). These techniques are consistent with the best practices for identifying stable, interpretable segment structures in tourism behavior studies [92].

Table 2.

Cluster profiles based on sustainability attitudes.

Statistical comparisons of the mean scores across the sustainability attitude items confirmed significant differences between the two clusters (p < 0.001), validating the segmentation. These results reinforce the usefulness of attitudinal segmentation for tailoring sustainable hospitality strategies to differentiate consumer values [93,94].

The final two-cluster solution revealed meaningful differentiation in sustainability awareness. Cluster 1 scored significantly higher on environmental concern, personal responsibility, and preference for sustainable travel experiences. Members of this cluster actively sought out eco-friendly hotels, valued environmental transparency, and were more likely to engage in green behaviors throughout their hotel stay. This profile aligns with previous findings on tourists who exhibit consistent sustainable preferences across service touchpoints [95].

On the other hand, Cluster 2 displayed lower sustainability awareness and minimal prioritization of environmental considerations in their travel decisions. Their preferences leaned toward convenience, price, and comfort rather than sustainability credentials. While not resistant to green practices, this segment tended to be passive in their engagement with sustainable hotel features unless such practices directly enhanced comfort or convenience [96].

4.3. Reliability and Validity of Measurement Constructs

To ensure the robustness and measurement quality of the proposed model, both perceived value dimensions (functional, emotional, social, ethical/environmental) and service journey stage-based constructs (pre-consumption value, consumption value, post-consumption value) were subjected to rigorous reliability and validity assessments. These constructs were operationalized based on the established literature on sustainable hospitality and service experience [13,44,77].

To establish construct validity, both convergent and discriminant validity were tested. Convergent validity was assessed through the average variance extracted (AVE) for each latent variable. As illustrated in Table 3, all the constructs yielded AVE values above 0.50, supporting the conclusion that a significant portion of variance is explained by the underlying indicators.

Table 3.

Reliability and validity results for the perceived value constructs.

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was then conducted using AMOS to validate the measurement model. The model demonstrated good fit across multiple indices: chi-squared/df = 1.87, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.046, and SRMR = 0.041, all of which fell within the recommended thresholds for acceptable model fit [97]. These results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Model fit summary.

According to widely accepted criteria, the chi-squared/df ratio below 3.00, CFI and TLI values of 0.90 or higher, RMSEA values of 0.06 or lower, and SRMR values under 0.08 reflect good model fit [98]. To enhance interpretability, Table 5 presents each fit index alongside its recommended threshold and interpretation.

Table 5.

Model fit indices and benchmark criteria.

Discriminant validity was examined using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, which compares the square root of the AVE for each construct with the inter-construct correlations. As shown in Table 6, the square root of each construct’s AVE (diagonal values) is greater than its correlations with other constructs (off-diagonal values), providing evidence that each construct is distinct from the others [99].

Table 6.

Discriminant validity matrix (Fornell–Larcker criterion).

These findings collectively confirm that the perceived value constructs used in this study exhibit satisfactory levels of reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity, supporting their appropriateness for subsequent multi-group analysis.

4.4. Multi-Group Comparison of the Perceived Value Across Clusters

To examine how tourists with differing levels of sustainability perception evaluate sustainable hotel practices across the guest journey, a multi-group structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis was conducted. Using k-means clustering, the participants were segmented into two groups: one with a higher perception of sustainability and the other with a lower perception. The primary aim was to investigate whether the strength of relationships between the perceived value dimensions, functional, emotional, social, and ethical/environmental, and the three stages of the guest service journey, pre-consumption, consumption, and post-consumption, differs significantly between these two clusters.

4.4.1. Path Relationships in the Pooled Model

The structural model was first tested on the full sample to assess the direct effects of each perceived value dimension on the three stages of the guest service journey. As shown in Table 7, the majority of the hypothesized relationships were positive and statistically significant (p < 0.05). Functional value demonstrated the strongest influence on the pre-consumption stage (β = 0.41, p = 0.000), while emotional value was most predictive of the consumption stage (β = 0.53, p = 0.000). For the post-consumption stage, both ethical/environmental value and social value showed strong effects (β = 0.47 and β = 0.39, respectively, both p < 0.001).

Table 7.

Hypothesis testing results—structural model.

However, not all the hypothesized paths were supported. Specifically, functional value did not significantly influence the post-consumption value (H1c: β = 0.29, p = 0.068), the social value did not significantly predict the pre-consumption value (H3a: β = 0.28, p = 0.072), and the ethical/environmental value had no significant effect on the pre-consumption value (H4a: β = 0.37, p = 0.083). These non-significant findings suggest that while these value dimensions may play important roles in other stages of the guest journey, their influence is not uniformly strong across all phases.

Overall, the results largely support the conceptual framework and confirm that multiple dimensions of perceived value contribute meaningfully to how tourists evaluate sustainable hotel practices throughout the guest experience, though with some variations in influence depending on the service stage and value type.

4.4.2. Group Differences in Path Strengths

To assess whether tourists with different levels of sustainability perception interpret value dimensions differently across the guest service journey, a multi-group analysis was conducted. As shown in Table 8, the strength of several path relationships varied between the two clusters, those with high sustainability perception and those with low sustainability perception.

Table 8.

Multi-group path coefficient comparison between the clusters.

Significant group differences were identified in five out of the twelve hypothesized relationships, with critical ratio differences (CRD) exceeding the 1.96 threshold, indicating statistical significance at the p < 0.05 level. The influence of the functional value on both the pre-consumption stage (CRD = 2.17) and the post-consumption stage (CRD = 2.01) was significantly stronger for Cluster 1 than for Cluster 2. Similarly, the impact of the social value on the post-consumption stage was greater for Cluster 1 (CRD = 2.20). The ethical/environmental value also exhibited stronger effects in Cluster 1 across all three stages: pre-consumption (CRD = 2.41), consumption (CRD = 2.35), and post-consumption (CRD = 2.58).

No statistically significant group differences were found in the path from the emotional value to the consumption stage, despite high standardized coefficients for both clusters. Additionally, the paths from the functional value to the consumption stage and from the social value to both the pre-consumption and consumption stages did not differ significantly between the clusters. These results indicate that Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 responded differently to certain perceived value dimensions across the service journey, as measured by structural path differences.

4.4.3. Interpretation of the Findings

The findings from both the full-sample structural model and the multi-group analysis provided detailed insights into how Chinese tourists perceive the value of sustainable hotel practices across the stages of the guest service journey. Overall, the results affirm that perceived value is a multidimensional construct, with distinct influences depending on the service stage and tourists’ sustainability orientation.

The pooled structural model results (Table 7) indicated that most hypothesized relationships between the perceived value dimensions and the guest journey stages were statistically significant. Emotional value was found to be the strongest predictor during the consumption stage (β = 0.53), highlighting the importance of emotionally resonant experiences with sustainable amenities and services during the hotel stay. Functional value emerged as the most influential factor in the pre-consumption stage (β = 0.41), suggesting that booking transparency, efficiency, and the visibility of sustainability credentials play a key role in shaping initial evaluations. Post-consumption perceptions were most strongly influenced by ethical/environmental value (β = 0.47) and social value (β = 0.39), indicating that guests derive meaning from moral satisfaction and social validation after their stay.

However, three hypothesized paths were not supported. These include the effect of the functional value on post-consumption perceptions (H1c), of the social value on pre-consumption evaluations (H3a), and of the ethical/environmental value on pre-consumption evaluations (H4a). These results suggest that the influence of perceived value types is stage-specific. For example, functional considerations may not be strongly linked to how guests evaluate the aftermath of their stay, and early-stage decisions such as hotel selection may not be driven by ethical or socially influenced motives.

The results from the multi-group SEM analysis (Table 4 and Table 8) indicate that tourists’ sustainability attitudes moderate the strength of value perception relationships. Tourists in Cluster 1 (high sustainability perception) reported stronger effects from the functional value in both the pre- and post-consumption stages and higher sensitivity to the ethical/environmental value across all three stages of the guest journey. These tourists also showed a stronger response to the social value in the post-consumption phase. In contrast, tourists in Cluster 2 (low sustainability perception) exhibited weaker path coefficients across most dimensions and stages. Their value assessments appeared to rely more heavily on functional and emotional attributes during the consumption stage, suggesting a less integrated perception of sustainability across the full-service journey. These findings underscore the differential processing of sustainable hospitality experiences across consumer segments and affirm the importance of attitudinal segmentation in understanding how sustainable value is constructed and evaluated by different types of travelers.

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion of the Clusters and Key Characteristics

The k-means cluster analysis identified two attitudinally distinct groups of Chinese tourists based on their orientation toward sustainability in the hotel context: Cluster 1—environmentally engaged travelers and Cluster 2—conventional comfort travelers. This segmentation aligns with the established frameworks in the sustainable tourism literature that distinguish tourists by their value-driven versus convenience-driven behavioral profiles [18,40]. These results reinforce calls within the literature to move beyond demographic segmentation and adopt more nuanced attitudinal and psychographic approaches to understanding sustainable consumer behavior [25,42].

Cluster 1, environmentally engaged travelers, was characterized by a high perception of sustainability, underpinned by strong environmental concern, a sense of personal responsibility, and a commitment to engaging with eco-conscious practices. Their attitudinal and behavioral orientation reflects the value–belief–norm (VBN) theory, which emphasizes how internalized environmental norms and moral obligations drive pro-environmental behavior [17,33]. Consistent with findings by Zhang (2022), these travelers—typically younger, urban individuals from Tier 1 cities—are increasingly willing to support eco-certified accommodations and are even prepared to pay a premium for authentic sustainable experiences [22]. This group assigned a significantly higher importance to sustainability-related values across the entire hotel service journey, particularly in the ethical/environmental and social dimensions during the post-consumption stage. Their receptivity to symbolic cues—such as eco-labels, third-party certifications, and transparency in reporting—supports the signaling theory proposition that sustainability information functions as a proxy for trust and service quality in the high-intangibility context of hospitality [51]. These findings also substantiate the multidimensional value framework presented in Section 2.4, demonstrating that this group derives not only functional value but also affective, moral, and social value from sustainable hospitality touchpoints [72,73,74].

In contrast, Cluster 2, conventional comfort travelers, exhibited lower environmental awareness and weaker alignment with sustainability-oriented decision-making. Although they did not explicitly reject sustainability, their service evaluations were less influenced by ethical or collective considerations. Instead, they prioritized emotional and functional value, especially during the consumption stage, where cleanliness, convenience, and comfort dominated their perceptions. This aligns with prior findings suggesting that many Chinese tourists—especially those from lower-tier cities or with limited exposure to sustainability education—are more influenced by practical benefits than abstract ethical ideals [18,31]. This group’s emphasis on in-stay functionality echoes insights from the infrastructure practice theory, which posits that built environments and service design can enable or constrain sustainable behavior depending on ease, clarity, and comfort [59]. For these travelers, sustainability practices must be seamlessly integrated into service design, such as via refillable dispensers or intuitive recycling systems, to be effective.

The empirical differences between the two clusters were most pronounced in several structural paths. Specifically, Environmentally Engaged Travelers exhibited significantly stronger path coefficients for ethical/environmental value across all three service stages, as well as for functional value in both the pre- and post-consumption stages, and social value in the post-consumption stage. This pattern reflects the temporally dynamic nature of sustainability perception, supporting the conceptualization of perceived value as a context-sensitive construct shaped by the progression of guest interactions throughout the service journey [46]. This reflects their holistic integration of sustainability into the travel experience, from intention and booking to post-stay engagement, echoing findings by Teng et al. (2023), who emphasized that emotional and moral congruence enhances tourist satisfaction in green hotel contexts [89].

The structural path differences between the two clusters were most evident in how they evaluated ethical/environmental value across all three service stages. Environmentally engaged travelers also reported stronger responses to functional value in the pre- and post-consumption stages and to social value in the post-consumption stage. These results underscore the temporally dynamic nature of perceived value, which, as outlined in Section 2.4, is shaped through a series of interactions across the pre-consumption, consumption, and post-consumption stages [46]. This pattern confirms that sustainable value is not static, but rather co-created through guest interaction, experience interpretation, and emotional engagement, aligning with the service-dominant logic [47].

For conventional comfort travelers, emotional value still played a moderate role during the consumption stage. This partially supports the findings of Lee (2011), who determined that even low-involvement tourists may respond positively to green practices when they are framed around convenience or emotional resonance rather than ethical obligation [31]. Their moderate engagement with sustainability also reinforces the importance of framing and contextual delivery, as advocated by Prebensen and Rosengren (2016), who emphasized that value co-creation begins before the actual service experience and must be consistently reinforced [55].

Overall, the cluster distinctions confirm the utility of attitudinal segmentation in sustainable hospitality. Tourists perceive and evaluate sustainability not uniformly, but through individualized mental models shaped by values, lifestyle, and motivational drivers [12,25,89]. This observation is consistent with prior segmentation research, including Dolnicar and Grün (2009) and Han (2021), who advocate for psychographic segmentation as a more predictive tool than demographic categorization in sustainability contexts [40,42]. By applying this segmentation lens to the entire hotel service journey, this study contributes to a more granular understanding of how tourists construct perceived value in sustainable hospitality. Cluster 1 tourists clearly prioritize symbolic, moral, and socially oriented sustainability attributes, while Cluster 2 travelers remain more attuned to functional benefits and emotional comfort. These findings offer both theoretical validation of the multidimensional value framework and practical guidance for designing differentiated sustainability strategies tailored to diverse Chinese tourist profiles.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This study advances the theoretical discourse on sustainable tourism and service experience by refining how perceived value is conceptualized, segmented, and measured within environmentally responsible hospitality contexts. First, it contributes to the perceived value theory by empirically validating a multidimensional and temporally dynamic framework of value construction. Unlike earlier models that treated perceived value as a static or unidimensional construct (e.g., Sweeney & Soutar, 2001 [74]), this study disaggregates value into four distinct but interrelated dimensions—functional, emotional, social, and ethical/environmental—and examines their roles across the pre-consumption, consumption, and post-consumption stages of the hotel guest journey [74]. This aligns with the findings of Sánchez-Fernández and Iniesta-Bonillo (2007) and others advocating for richer, more experience-sensitive value models, particularly in sustainability-driven service environments [42,73].

The stage-specific approach adopted in this study enhances the existing theoretical models by demonstrating that value perception evolves in response to service touchpoints and temporal progression. This perspective supports the argument that perceived value is contextually constructed, not simply a cumulative output, and varies by both the attitudinal disposition of the guest and the stage of service interaction [46,47]. These findings respond to recent calls for integrative frameworks that merge sustainability signals with consumer psychology in hospitality and tourism, providing an empirical foundation for theory development that more precisely accounts for how and when sustainability efforts are interpreted as meaningful by diverse traveler segments.

Second, by integrating the service journey framework into the context of sustainable hotel experiences, the study offers new theoretical insight into how perceived value is co-created from pre-stay expectations to post-stay reflections. The finding that the emotional value is most salient during the consumption stage, while the functional and ethical/environmental values are more prominent in the pre- and post-consumption stages, adds temporal specificity to the concept of value co-creation within the logic of the service-dominant theory [47]. This differentiation reinforces the notion that sustainability perception is not a generalized mindset but a stage-specific cognitive–affective response, shaped by the type of engagement and service context. These findings resonate with those of Lee (2011), who emphasized that pro-environmental behaviors in tourism are driven by a dynamic interplay of emotional, cognitive, and contextual factors that evolve over time [30].

Third, the study provides empirical support for attitudinal segmentation as a powerful theoretical lens for understanding heterogeneity in sustainable consumer behavior. Through the application of k-means clustering, two distinct profiles, environmentally engaged travelers and conventional comfort travelers, were identified. This segmentation model aligns with prior research by Prayag et al. (2017) and Dolnicar and Grün (2009), who found that psychographic variables, particularly personal values and environmental concern, offer greater explanatory power than demographics in predicting sustainable travel behavior [40,64]. The distinct patterns in value perception between clusters in this study affirm that internalized beliefs and cognitive orientations not only shape general preferences, but also moderate how sustainability is evaluated across different service stages.

Additionally, this research builds on that of Han et al. (2023) [17], who documented a growing attitudinal divergence among Chinese tourists toward sustainability. While previous studies primarily identified an emerging segment of environmentally conscious travelers in Tier 1 cities [17], this study extends those findings by empirically mapping how these attitudinal differences manifest in the evaluation of sustainable service features throughout the guest journey. In doing so, it bridges the gap between abstract environmental concern and real-time behavioral responses, offering a more applied perspective on the attitudinal antecedents of green hotel experience evaluations.

Finally, the integration of attitudinal segmentation, multidimensional value theory, and service journey temporality contributes a novel framework that links sustainability orientation to stage-specific service evaluations. This reinforces the theoretical relevance of adopting experience-based and psychologically informed models in sustainable hospitality research. By empirically validating how value is interpreted differently across guest segments and service phases, this study provides a granular and behaviorally grounded contribution to the broader field of sustainable service theory, enabling more precise and theoretically coherent approaches to future segmentation, positioning, and value co-creation strategies.

5.3. Managerial Implications

The identification of two attitudinally distinct guest segments, environmentally engaged travelers and conventional comfort travelers, offers actionable guidance for hospitality managers aiming to tailor sustainability strategies to diverse consumer profiles. To effectively implement these insights, sustainability initiatives should be designed with sensitivity to both attitudinal differences and the temporal stages of the hotel service journey. This dual lens facilitates alignment between service delivery and perceived value, thereby enhancing both guest satisfaction and the impact of sustainability programs.

For environmentally engaged travelers, who demonstrate high responsiveness to the ethical and social value dimensions throughout the guest journey, sustainability messaging and service design must emphasize authenticity, transparency, and long-term environmental responsibility. During the pre-consumption stage, hotels should highlight third-party certifications, carbon offset options, and partnerships with local conservation or community initiatives to establish trust. In the consumption stage, storytelling elements—such as narratives around local sourcing, biodiversity conservation, or fair labor practices—can reinforce alignment with these guests’ personal values. In the post-consumption stage, personalized communications (e.g., environmental impact summaries showing energy or water saved) can further validate the guest’s contribution, reinforcing brand trust and loyalty. These practices directly respond to the value dimensions outlined in Section 2.4 and are known to enhance guest identification and advocacy behavior, especially among sustainability-oriented segments [44,73].

In contrast, conventional comfort travelers, who prioritize functional and emotional value, especially during the in-stay phase, require a more pragmatic approach. Sustainability features should be framed in terms of convenience, comfort, and enhanced sensory experience, rather than abstract environmental benefits. For instance, highlighting how energy-efficient technologies improve room temperature stability, or how locally sourced ingredients enhance food quality, is likely to resonate more with this segment. Emotional value can be supported through aesthetically pleasing, biophilic design and calming, eco-conscious environments. As shown in the literature [31], guests with lower environmental orientation may still appreciate sustainability initiatives when they are clearly positioned as value-enhancing rather than value-restricting.

Across both segments, message consistency throughout the guest journey is critical. Sustainability should be embedded into the brand narrative in a coherent, credible, and visible manner, from booking through check-out and follow-up engagement. Digital platforms should display eco-certifications and allow guests to select green options during booking. In-room materials should explain how systems operate and how guest behaviors support sustainability goals. Post-stay communications can offer data-driven sustainability feedback and incentivize repeat green behavior. As supported by previous research [13], maintaining this coherence across all touchpoints reinforces perceived authenticity and mitigates green skepticism, particularly among environmentally attuned guests.

Importantly, the use of attitudinal segmentation, as demonstrated through k-means clustering in this study, provides a more effective framework for hospitality managers than traditional demographic segmentation. As tourist behavior increasingly reflects psychographic and value-based motivations, hospitality businesses should consider incorporating attitudinal variables into CRM systems, guest feedback mechanisms, and personalized marketing campaigns. This allows for more precise targeting, tailored service offerings, and strategic resource allocation. Particularly in evolving markets such as outbound Chinese tourism, where expectations are rapidly shifting, such segmentation can support proactive service adaptation [17,42].

In summary, aligning sustainability strategies with the emotional, ethical, and functional value priorities of different tourist segments, while ensuring consistent delivery across the service journey, enables hotels to meet diverse guest expectations, enhance brand credibility, and strengthen their contribution to the long-term advancement of sustainable hospitality.

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

6.1. Conclusions

This study examined how Chinese tourists evaluate sustainable hotel practices through the lens of multidimensional perceived value—functional, emotional, social, and ethical/environmental—across the pre-consumption, consumption, and post-consumption stages of the guest journey. Drawing on the perceived value theory, service experience frameworks [46,49], and attitudinal segmentation [40,64], the study builds on a well-established body of literature while addressing recent calls for more dynamic, values-based approaches to sustainability segmentation in tourism.

Using data from 400 Chinese tourists in five-star hotels in Phuket, Thailand, structural modeling confirmed that value perceptions are stage-specific and moderated by sustainability orientation. The emotional value had the strongest effect during the stay, the functional value influenced pre-stay decision-making, and the ethical/social value shaped post-stay reflections.

K-means clustering revealed two distinct segments: environmentally engaged travelers, who responded strongly to the ethical, social, and functional values across all stages, and conventional comfort travelers, who were more responsive to emotional and functional aspects, particularly during the stay. These findings affirm the importance of both temporal and attitudinal factors in shaping sustainable hospitality experiences.

The study contributes to the sustainable tourism theory by advancing a dynamic, segment-sensitive model of perceived value. It also offers practical guidance for hotels to tailor sustainability strategies to guest values, enhancing engagement and loyalty in an increasingly sustainability-conscious market.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

While this study offers meaningful contributions to sustainable tourism research, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sample was limited to Mainland Chinese tourists staying in five-star hotels in Phuket, Thailand. While this context allowed for a deep and focused exploration of value perception within a specific market segment, it also constrains the generalizability of the findings to other tourist nationalities, hotel categories, and destinations. Future studies should consider comparative cross-cultural research involving tourists from different countries or regions to assess how cultural norms and policy environments shape sustainability perceptions. In addition, extending the framework to mid-range or boutique hotels could reveal whether service tier influences how tourists construct perceived value in response to green practices. These comparative approaches would improve the external validity and broader applicability of the segmentation model developed in this study.

Second, the use of self-reported, cross-sectional survey data for attitudinal segmentation presents limitations in capturing the dynamic nature of tourist behavior. Although k-means clustering provided clear differentiation between the segments, alternative methods such as latent class analysis or longitudinal tracking could offer more robust insights into how sustainability perceptions evolve over time.

Third, the conceptual framework focused on four core value dimensions—functional, emotional, social, and ethical/environmental. While comprehensive, it did not include potentially influential constructs such as trust, brand image, or perceived authenticity, all of which may shape evaluations of sustainable services. Future studies could enrich the model by exploring these variables or testing mediators such as satisfaction, perceived risk, or psychological distance.

Fourth, this study employed a quantitative approach using structural equation modeling (SEM). While suitable for testing relationships, the absence of qualitative data limits the understanding of the deeper meanings tourists assign to sustainability. Incorporating qualitative methods, such as interviews, focus groups, or ethnographic observation, could reveal more nuanced interpretations and contextual insights. A mixed-methods design may also capture real-time shifts in guest perception across the service journey.

Lastly, the questionnaire was administered in both English and Mandarin to accommodate the participants’ language preferences. While the Chinese version was translated and validated using the item–objective congruence (IOC) method by five experts, including two Chinese language lecturers from higher education institutions and three senior hotel professionals with extensive experience in the Chinese tourist market, some degree of language or cultural interpretation bias may still have been present. Variations in how terms such as “sustainability,” “luxury,” or “value” are perceived across linguistic and cultural contexts may have influenced participant responses. Future studies should consider incorporating back-translation techniques and cognitive interviews to further enhance cross-language consistency and conceptual equivalence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.L. and T.C.; methodology, N.L.; software, N.L.; validation, T.C.; formal analysis, N.L.; investigation, N.L.; data curation, N.L. and T.C.; writing—original draft preparation, N.L.; writing—review and editing, N.L. and T.C.; visualization, N.L.; supervision, T.C.; project administration, N.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee in Human Research at the National Institute of Development Administration (NIDA), Thailand (COA No. 2023/0117). The research complies with international guidelines for human research protection, including the Declaration of Helsinki, CIOMS Guidelines, and the Belmont Report.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author, TC. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions related to human participant data.

Acknowledgments

This paper is part of the PhD thesis titled Five-star Hotel Service Quality Management Model to Accommodate High-end Chinese Tourists in Phuket, Thailand, undertaken at the Graduate School of Tourism Management, National Institute of Development Administration (NIDA).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- UNWTO. Tourism Stakeholders Invited to Share Progress on Climate Action; United Nations World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2023; Available online: https://www.unwto.org/news/tourism-stakeholders-invited-to-share-progress-on-climate-action (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- ASEAN Secretariat. The Future of ASEAN Tourism: A Transformative Recovery Strategy [Full Report]; ASEAN Secretariat: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bittner, N.; Bakker, N.; Long, T.B. Circular Economy and the Hospitality Industry: A Comparison of the Netherlands and Indonesia. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 444, 141253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makoondlall-Chadee, T.; Bokhoree, C. Environmental Sustainability in Hotels: A Review of the Relevance and Contributions of Assessment Tools and Techniques. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, M.A.; Juhaizi, M.S.; Zamuin, N.Z.I.B.; Fuza, Z.I.M.; Isa, S.M. Sustainability and Technology Influence Towards Hotels Guest Satisfaction. Int. J. Res. Innov. Soc. Sci. 2024, 8, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Väisänen, H.-M.; Uusitalo, O.; Ryynänen, T. Towards Sustainable Servicescape—Tourists’ Perspectives of Accommodation Service Attributes. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 110, 103449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhofer, B.; Buhalis, D.; Ladkin, A. Smart Technologies for Personalized Experiences: A Case Study in the Hospitality Domain. Electron. Mark. 2015, 25, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Rahman, M.N.; Hassan, T.H.; Abdou, A.H.; Abdelmoaty, M.A.; Saleh, M.I.; Salem, A.E. Responding to Tourists’ Intentions to Revisit Medical Destinations in the Post-COVID-19 Era through the Promotion of Their Clinical Trust and Well-Being. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.-S. Developing a Conceptual Model for the Post-COVID-19 Pandemic Changing Tourism Risk Perception. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantakopoulou, I. Does Health Quality Affect Tourism? Evidence from System GMM Estimates. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 73, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvan, E.; Dolnicar, S. Measuring Environmentally Sustainable Tourist Behaviour. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 59, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang-Van, T.; Vo-Thanh, T.; Wang, J.; Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, N. Green Hotel Practices and Consumer Revisit Intention: A Mediating Model of Consumer Promotion Focus, Brand Identification, and Green Consumption Value. J. Vacat. Mark. 2024, 30, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, J.; Lovelock, C. Services Marketing: People, Technology, Strategy; World Scientific: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, E. Cross-Cultural Aspects of Tourism and Hospitality: A Services Marketing and Management Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saengchai, S.; Hasoontree, N. Sustainable Development Tourism on Supply Chain Management of Tourism in Phuket. J. Manag. Inf. Decis. Sci. 2021, 24, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbs, P. Chinese Tourism and Its Impact to Thailand Economy. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 10, 182–199. [Google Scholar]

- Han, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, Y. Internalizing Social Norms to Promote Pro-Environmental Behavior: Chinese Tourists on Social Media. J. China Tour. Res. 2023, 19, 443–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.; Qiu, X.; Wang, K.; Bu, N.; Cheung, C.; Zhang, N. Exploring Chinese Sustainable Tourism: A 25-Year Perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]