Abstract

The agricultural sector stands at the intersection of economic, ethical, and environmental concerns, presenting complex challenges for sustainable development. This study investigates how ethical attitudes, conceptualized at political (e.g., perceptions of transparency, anti-corruption, and policy fairness) and social levels (e.g., community engagement, labor standards, and social equity), influence ethical behavior within Romanian agricultural organizations. Additionally, it explores the impact of sector-specific and organizational ethics on the adoption of social responsibility (SR) practices. Using a quantitative research approach, the study employed a structured questionnaire covering four key dimensions: political and social ethics, corporate responsibility, environmental sustainability, and ethical management in agriculture. The findings suggested that Romanian agricultural companies could improve their long-term competitiveness by incorporating ethical governance, sustainable business practices, and stakeholder engagement into their strategic frameworks. These findings suggest that Romanian agricultural companies can enhance their long-term competitiveness by embedding ethical governance, sustainable business models, and active stakeholder engagement into their strategic frameworks. This research contributes to the theoretical discourse by demonstrating how contextual ethical attitudes influence SR, providing a nuanced understanding of the interplay between economic performance, social equity, and environmental responsibility in an emerging economy.

1. Introduction

The agricultural sector is not only a fundamental pillar of global food security but also a field where ethical, economic, and environmental challenges intersect. The agricultural sector plays a central role in ensuring global food security, yet it faces significant ethical, environmental, and economic challenges that require urgent attention [1]. While ethical business practices are widely acknowledged as important, the real concern lies in understanding their impacts on economic performance, reputation, and long-term sustainability within specific industries. However, as the global population continues to grow, the ethical concerns surrounding agricultural practices have become increasingly complex [2,3]. Although there is an urgent need to increase food production to meet global demand, this must be balanced with the imperative to mitigate the environmental and social impacts of intensive agricultural practices [4,5]. Sustainable food systems promote resource management, biodiversity conservation, and fair distribution [1].

Agriculture operates at the crossroads of social, ecological, and economic systems, leading to unique ethical challenges. In Romania, these issues are particularly pressing due to the rapid intensification of the climate crisis, to which agriculture is a significant contributor. In Romania, recent climate trends—such as a 1.5 °C temperature increase over the past 50 years and frequent droughts—pose significant challenges for agricultural sustainability, which in turn raise complex ethical considerations for producers and policymakers [6]. Uncertainties about future harvests, labor shortages, and the aging and migration of the rural population directly impact the ethical attitudes of agricultural businesses. Ethical management in this sector requires balancing economic interest with social and environmental responsibilities, adhering to principles that guide managers toward responsible and sustainable decision-making.

As with any human endeavor, agricultural activities should be evaluated ethically. There is an increasing shift toward incorporating sustainable, environmentally friendly practices. This paper emphasizes the strong correlation between an organization’s ethical behavior and its promotion of social responsibility, which are key pillars for ensuring a sustainable future. Interest in climate-resilient food systems has increased due to the growing consequences of climate change on food production and the welfare of vulnerable groups [7].

Both the global economy and human survival depend heavily on agriculture. Sustainability and ethical ideals are becoming more widely acknowledged as vital elements of contemporary farming methods. Environmental sustainability, fair labor standards, and animal care are just a few topics covered by ethical considerations in agriculture. The goal of sustainable agriculture is long-term viability through biodiversity promotion, resource conservation, and environmental impact reduction. Farmers may enhance the quality of their produce and support the resilience and health of ecosystems for coming generations by implementing moral and sustainable farming methods. Both individual and institutional variables have an impact on ethical behavior and ethical dilemmas in the agricultural industry. Individual attitudes, beliefs, and wants, as well as moral development, ethical sensitivity, and personal values, all influence ethical behavior [8]. Sensitivity to the ethical challenges they face and the agricultural producer’s beliefs about what is right and wrong both promote ethical behavior. Rather than being raised by external or environmental factors, these problems are rooted in internal desires and urges [9]. Ethical challenges in agriculture arise not only from external environmental conditions but also from internal factors, such as organizational culture, leadership styles, and individual moral reasoning [10].

By using natural resources more efficiently and enhancing climate change resilience, sustainable farming practices aim to protect the ecosystem [11]. Despite having multiple meanings, sustainable agriculture is often associated with positive outcomes [12]. The scientific community frequently focuses its research on sustainable agriculture on environmental challenges pertaining to the utilization of the environment. The advantages of social responsibility, such as how consumers view businesses and goods and how it boosts customer happiness and loyalty, are highlighted by [13]. In addition to raising employee happiness, social responsibility makes the business a more desirable place to work [14]. As a result, social responsibility enhances businesses’ reputations by increasing consumer awareness of their brands and goods [15]. From an ethical standpoint, social fairness, environmental preservation, and economic efficiency are all important aspects of sustainable development [14]. To maintain the well-being of ecosystems and human societies, for instance, agricultural techniques like crop rotation, the prudent application of fertilizers and pesticides, and biodiversity conservation are not only technically sound but also morally required [16]. A comprehensive, ecosystem-based approach is integral to the concept of sustainable agriculture, in which plants, soil, water, the environment, and living organisms all coexist in a state of harmonious balance [17]. Ethics research in the agricultural sector identifies morally relevant issues by applying the concepts of justice, sustainability, and responsibility. In recent years, there has been a growing international emphasis on systematically measuring and enhancing social responsibility (SR) within the agribusiness sector. Diverse approaches have emerged, shaped by cultural, regulatory, and socio-political contexts. For instance, in Europe, the Farm to Fork Strategy and the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) provide a robust framework for promoting sustainable and ethical practices, including metrics for reducing pesticide use, conserving biodiversity, and improving animal welfare [18]. In countries such as The Netherlands and Denmark, platforms like the Sustainable Agriculture Initiative (SAI) and the Danish Ethical Trade Initiative (DECP) provide comprehensive guidelines for SR implementation and assessment [19,20]. Conversely, in India, SR frameworks are still evolving, often influenced by challenges such as land rights disputes, social inequalities, and limited regulatory oversight [21]. Additionally, the B Corp certification process, as demonstrated in the Italian context, plays a pivotal role in supporting transparent and comprehensive CSR disclosure, integrating environmental and social impact into corporate accountability [22]. These international approaches underscore the importance of adopting a multidimensional and context-sensitive perspective when evaluating social responsibility (SR) in agribusiness, integrating ethical, political, and environmental considerations into both practice and assessment.

Social responsibility refers to the notion that companies should answer to both their stakeholders and other interested people, including suppliers, friendly merchants, and—above all—customers and the communities in which they operate. The SR highlights the need for businesses not only to adhere to the law but also to take the initiative to fulfill their social obligations [23].

To address these challenges, the present study aims to examine the intricate interrelations between ethical attitudes at political, social, organizational, and sectoral levels within the Romanian agricultural sector. Specifically, it aims to investigate how ethical governance and sustainable management practices impact social responsibility (SR) in the agribusiness sector. To achieve this goal, the research focuses on three key objectives: (1) to analyze the relationship between ethical attitudes in the agricultural sector and those at political and social levels; (2) to explore the association between organizational-level ethics and broader political, social, and sectoral ethical attitudes; and (3) to assess the impact of ethical attitudes on the adoption of CSR practices within agricultural organizations.

2. Social Responsibility of Companies in the Agricultural Sector

More than any other sector, agriculture is characterized by a significant dependence on natural resources and has a considerable impact on the environment and biodiversity; therefore, companies in this sector are very exposed to the criticism of environmental associations and civil society in general [24]. Agricultural production involves the use of land and water, as well as pesticides, fertilizers, livestock, and energy. Globally, irrigated agricultural activities use almost 40% of the planet’s surface and 70% of water [25]. Agriculture contributes up to 22% of GHG emissions globally through livestock activities, land use change, and various inputs and processing steps of food systems [26]. As global issues grow, significant action is needed from all stakeholders to mitigate the impact of climate change, inequalities, and persistent human rights risks in agricultural supply chains. While business action and innovation are an essential part of corporate responsibility, governments must build an enabling economic environment, legal systems, and policy frameworks that support social responsibility. In Romania, the agricultural industry was essential to economic growth, particularly prior to 1989, when about 60% of Romanian people relied on it as their main source of income [27].

Social responsibility (SR) represents the voluntary behavior of companies, to surpass legal requirements through a comprehensive business model, which ensures an ethical balance between economic development, environmental protection, and social promotion [20]. Companies, retailers, and investors in the agricultural sector increasingly need innovative production systems and a transition to sustainable agriculture. Agricultural enterprises can mitigate negative environmental impacts and contribute positively to the environment by using natural resources sustainably, using good agricultural practices and technologies, adapting to climate change, reducing GHG emissions, and protecting habitats for different species of plants and animals [26]. Companies in the agriculture sector, particularly the biggest ones, may be compelled to adopt socially responsible practices due to the increased public awareness of the industry and perceived external pressures [28]. But often, the socially responsible actions of these companies are less substantial than their stated commitments [29].

Because agriculture and the environment are closely related, several researchers are examining the extent to which social responsibility should be extended [30] or, more specifically, if this duty should encompass the whole food supply chain or just the company’s limits. Effective SR can affect the entire supply chain [31]. In addition, research has found that when SR extends to the entire supply chain, it can help reduce greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture [32]. Some authors have also demonstrated that an agrifood company with proactive, sustainable behaviors can also influence other interested parties [33]. A business that acts unethically runs the danger of harming the reputation of some or all of its affiliated businesses when social responsibility does not encompass the whole food supply chain [34].

The specialized literature reveals that social responsibility generates benefits with added value, by affecting consumers’ perceptions of companies and products, while increasing consumer loyalty and satisfaction [13]. The latter leads to a greater willingness to pay for the products of socially responsible companies [35]. In addition, SR increases the company’s attractiveness as an employer, while increasing employee satisfaction [14]. Social responsibility has been interpreted as a competitive advantage strategy for value creation in agrifood companies. The evolution of competitive dynamics has allowed companies to design their business activities in the context of value creation models aimed at meeting the emerging needs of citizen-consumers. In addition, firms focus on productive models centered on protecting natural and environmental resources, as well as consumer protection, where social responsibility is a competitive lever.

These concerns should characterize organizational culture and guide decision-making and business processes. Consequently, competition should take place based on promoting the distinctive values generated by social responsibility that can improve the reputation of companies. Businesses in the agricultural sector need to develop diversity and discrimination policies; have transparent procedures overseen by internal and external supervisors; be able to offer equal opportunities to all; have safe working conditions; have fair compensation and rewards policies; and be in compliance with laws, financial regulations, and other government practices, supply chain, and pricing. Additionally, they need to be more conscious of environmental preservation, recycling, energy and water use, emissions, technical resources, and the utilization of nature. It takes more than a manager or shareholder’s good intentions to integrate organizational and social ethics under the same policy agenda.

3. Materials and Methods

The research employed a quantitative approach to investigate the relationships between ethical attitudes at the political, social, and organizational levels within the agricultural sector. The study was centered on three key research hypotheses:

H1.

Ethical attitudes at the agricultural sector level (EAAS) are positively correlated with ethical attitudes at the political and social levels (EAP/EAS).

H2.

Ethical attitudes at the organizational level within the agricultural sector are positively correlated with ethical attitudes at the political, social, and sectoral levels.

H3.

Social responsibility (SR) is positively correlated with ethical attitudes at the organizational (EAO) and sectoral levels in agriculture.

3.1. Research Design

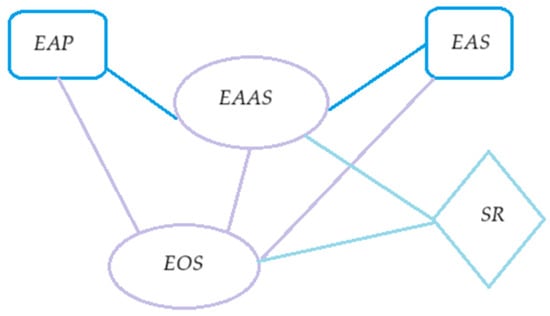

A correlational research design was selected to assess the relationships between the identified variables. The study aimed to quantify the influence of ethical attitudes from political and social domains on the agricultural sector, as well as the role of social responsibility at the organizational level. To achieve this, a structured questionnaire was developed and distributed to participants within the agricultural sector. Figure 1 illustrates the model structure, including paths from political (EAP), social (EAS), agricultural sector (EAAS), and organizational (EAO) ethical attitudes to social responsibility (SR).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

3.2. Data Collection

By querying the database available on www.coduricaen.ro, companies with production activities in the agricultural sector in Romania were randomly selected. Simple random sampling represents a random selection of elements for a sample. This sampling technique is implemented where the target population is considerably large. The questionnaire was sent to a number of 450 companies in Romania, with a main CAEN Code in the field of Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing, so as to cover all the counties of the country. The survey was conducted between March and April 2024, achieving a response rate of 61%, resulting in 275 validated questionnaires. The sample included businesses of various sizes: 47.3% of respondents worked in small enterprises with fewer than 50 employees, 34.2% in medium-sized enterprises with 51–100 employees, and 13.8% in companies with 101–250 employees. Additionally, 11 respondents (4.7%) represented large enterprises with over 251 employees. Regarding territorial representation, the sample covered a broad geographic distribution across Romania. Companies were headquartered in counties including Alba (8), Arad (5), Argeș (4), Bacău (8), Bihor (4), Bistrița-Năsăud (2), Botoșani (4), Brăila (8), Brașov (6), Buzău (6), Călărași (20), Caraș-Severin (1), Cluj (2), Constanța (13), Covasna (2), Dâmbovița (5), Dolj (14), Galați (9), Giurgiu (5), Hunedoara (4), Ialomița (13), Iași (14), Ilfov (6), Maramureș (1), Mehedinți (3), Mureș (4), Neamț (5), Olt (10), Prahova (10), Sălaj (3), Satu Mare (8), Sibiu (2), Suceava (1), Teleorman (16), Timiș (14), Tulcea (8), Vâlcea (1), Vaslui (12), and Vrancea (14). This comprehensive sample structure ensured representativeness in terms of both business size and territorial distribution, supporting the robustness of the study’s findings regarding ethical attitudes and SR practices in Romania’s agricultural sector.

The questionnaire was designed in three sections: (i) The first section addressed ethical attitudes at the political and social levels, using a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) to measure agreement on key ethical statements. (ii) The second section focused on ethical attitudes at the organizational and sectoral levels in agriculture, with questions assessing internal ethical practices and adherence to social responsibility standards. (iii) The final section explored the perceived influence of social responsibility on organizational decision-making and overall performance in the agricultural sector.

The sample consisted of managers and executives from agricultural organizations, policymakers, and other stakeholders with direct knowledge of the sector. However, the present analysis treated these sectors as a combined sample and did not provide disaggregated analyses by sector; this limitation has been explicitly acknowledged, and future research is recommended to explore sector-specific differences.

3.3. Variables and Hypotheses Testing

To test the research hypotheses, ethical attitudes at the political, social, and sectoral levels were treated as independent variables, while social responsibility and organizational ethics in the agricultural sector were treated as dependent variables.

For Hypothesis 1, correlation analysis was employed to measure the impact of political and social ethical attitudes on those within the agricultural sector.

For Hypothesis 2, regression analysis was used to assess the relationship between ethical attitudes across the political, social, and agricultural sectoral levels and their influence on organizational ethics.

For Hypothesis 3, a combination of correlation coefficients and regression models was applied to explore the interconnectedness of social responsibility and ethical attitudes at the organizational and sectoral levels in agriculture.

3.4. Data Analysis

The collected data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, 26th Version, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA, where correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the strength and direction of relationships between variables. Multiple regression models were employed to test the influence of ethical attitudes from one level (political or social) on another (sectoral or organizational).

The findings were evaluated based on statistical significance, with p-values set at <0.05 to determine the strength of the relationships between the ethical attitudes and social responsibility. The analysis also included the use of structural equation modeling (SEM) to explore potential indirect effects and deeper correlations between variables.

4. Results

The descriptive statistics of the index variables provided insights into how the 275 survey respondents evaluated the ethical attitudes within the agricultural organizations they represented. Table 1 presents the means, medians, standard deviations, and value ranges for each variable.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of index variables.

Regarding political ethical attitudes, the mean score was 3.00 on a 1-to-5 scale, where 1 indicated very low and 5 indicated very high. The standard deviation of 1.14 suggested a considerable variability in responses, with scores ranging from a minimum of 1 to a maximum of 4.60. This variability may reflect the diverse political contexts across Romania, where differing local governance structures and policy enforcement levels can influence how agricultural businesses perceive and adopt ethical practices.

For ethical attitudes at the social level, the mean score was slightly lower at 2.94, with a standard deviation of 0.81 and values ranging from 1.57 to 4.57. This indicated a moderately positive perception of social ethics yet also highlighted inconsistencies across different regions and company sizes. It suggested that while some respondents recognized the importance of ethical behavior in social interactions, others may face challenges in operationalizing these values within their communities and stakeholder relationships.

The agricultural sector’s ethical attitudes presented a mean score of 2.64, with scores spanning from 1 to 4.43 and a standard deviation of 1.09. This relatively lower average may indicate that systemic ethical considerations in the sector were less consistently implemented, possibly due to structural barriers, limited regulatory pressures, or resource constraints.

Regarding social responsibility (SR), the mean score was notably higher at 3.59, with values ranging from 1.89 to 4.78. This suggested that respondents perceived their organizations as relatively proactive in fulfilling social obligations, particularly those that aligned with environmental sustainability and stakeholder expectations. However, the observed variability in SR scores also implied that these practices may not be uniformly adopted across all surveyed organizations.

Taken together, these descriptive results illustrate the nuanced landscape of ethical attitudes and CSR engagement in Romanian agribusiness. The variations observed across political, social, sectoral, and organizational levels point to the complex interplay of internal and external factors shaping ethical behavior. These findings set the stage for a more in-depth analysis of the hypothesized relationships, providing valuable context for understanding the determinants of ethical governance and sustainable practices in the sector.

The first step in creating the index variables consisted in selecting the necessary items to measure the dimension of research interest. To measure the following dimensions, index variables were developed by adding up the scores of the individual items in the questionnaire’s subsections: political, social, and agricultural ethical attitudes; the company’s social responsibility attitude; and ethical attitudes at the agricultural level. In order to make the case that the items in the index represent the same idea and may be included in the same index, the second stage in creating the variables was to look at the relationships between the items. The final step in constructing the index variables was validating them to ensure that they measured what they were intended to measure.

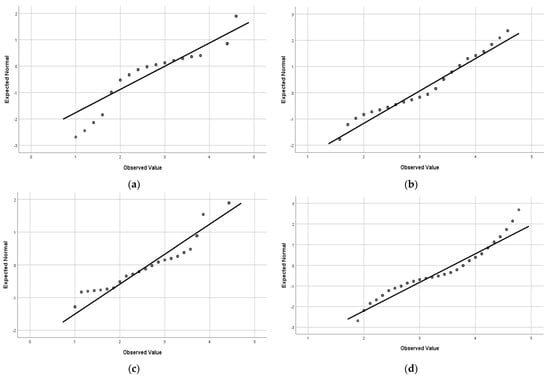

Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient used correlations between the constituent items of the index variable to determine whether its items measured the same dimension. This step of the research was particularly important, for this reason, Cronbach’s Alpha was calculated for each index variable, the results being centralized in Table 2. Cronbach’s alpha values exceeding 0.70 revealed a very good internal consistency. The “Number of items” column in Table 2 refers to the number of questionnaire items aggregated to create each index variable, providing context for the calculation of internal consistency (Cronbach’s Alpha) for these constructs. The Q-Q plot was a graphical tool that helped us evaluate whether the data set had a normal distribution. Figure 2 visualizes a linear distribution of data for the ethical attitudes political level variable, the points on the Q-Q plot deviate slightly from the straight line, and the distribution therefore has a longer tail on the left. Being left-skewed (or negatively skewed) meant that the data had values slightly away from the normal distribution. For the ethical attitudes social level variable, a linear distribution was also observed, with a slight deviation of the points from the normal distribution. At the same time, for the variable ethical attitudes in the agricultural sector, by analyzing the Q-Q plot graph, a linear fit of the distribution of points was observed, with a deviation at the ends. The lower end of the Q-Q plot deviates slightly from the straight line, with the distribution being slightly negatively skewed to the left from the normal distribution. For the corporate social responsibility variable, the Q-Q plot graph highlights a distribution with a very small or negligible deviation at the ends, with a linear fit for the normal distribution. The upper end of the plot deviates very slightly from the straight line, with the distribution being slightly positively skewed to the right from the normal distribution.

Table 2.

Level of internal consistency for index variables, across sections of survey.

Figure 2.

Q-Q plot of the distribution for the analyzed variables: (a) Ethical attitudes political level. (b) Ethical attitudes social level. (c) Ethical attitudes agricultural sector. (d) Social responsibility.

To determine the relationship between the specific variables of this research, namely, ethical attitudes at the political level (EAP) and ethical attitudes at the social level (EAS), ethical attitudes at the organizational level (EAO), ethical attitudes specific to the agricultural sector (EAAS), and social responsibility (SR), it used the Pearson correlation coefficient. Table 3 reveals the presence of a statistically significant correlation between the EAP and EAS variables (r = 0.846; p < 0.001), a strong correlation between EAS and SR (r = 0.935; p < 0.01) and between SR and EAO (r = 0.932; p < 0.01), and a moderate correlation between EAAS and SR (r = 0.765 < p < 0.01). A high intensity correlation can also be observed (r = 0.866) between ethical attitudes at the political level and ethical attitudes at the level of the agricultural sector.

Table 3.

Pearson correlation.

The research analyzed the correlation between ethical attitudes at the social and political levels (independent variables) and ethical attitudes at the organizational level, represented by the company’s internal ethical environment (dependent variable). In the case of multiple linear regression, the effect size indicator was r2. According to the information in Table 4, the coefficient of determination, r2 = 0.843, indicated that 84.30% of the variance in ethical attitudes at the organizational level, as defined by the company’s internal ethical environment, could be explained by the variance in the independent variables (ethical attitudes at the political and social levels). Therefore, we could conclude that 84.30% of the ethical attitude at the organizational level was determined by the ethical attitudes at the political and social levels and that these attitudes positively influenced ethical behavior at the organizational level.

Table 4.

Linear regression indicators for the variable’s ethical attitudes at the political and social levels and ethical attitudes at the organizational level.

Thus, the regression equation can be defined by the form

The impact of ethical attitudes at the organizational and sectoral level in agriculture on social responsibility highlights the role of ethical practices, such as the use of renewable resources, the reduction in pesticide use, and the promotion of organic agriculture, on the entire sector and on the organization that can contribute to a more responsible approach to society and the environment. Table 5 presents the unstandardized (β) and standardized (beta) regression coefficients and the results of the t-tests for each of these coefficients.

Table 5.

Linear regression indicators for the variable’s ethical attitudes at the political and social levels and ethical attitude at the organizational level.

The unstandardized coefficient for the constant is a = 0.108 and represents the intercept. The regression equation can now be written as follows:

predict the increase in social responsibility based on the ethical attitudes adopted at the organizational level in the company’s internal environment but also at the sectoral level within the analyzed field.

There was a statistically significant, medium-intensity positive correlation between the index variables of the company’s social responsibility and ethical views in the agriculture sector (r = 0.765; p < 0.001). However, the correlation between the company’s variable social responsibility index and its organizational level ethical attitude, as measured by the company’s variable internal ethical environment, demonstrated the existence of a statistically significant, positive, very high intensity link (r = 0.932; p < 0.001). Although the coefficient for EAO was not statistically significant (p = 0.119), this path was retained in the model to maintain consistency with the theoretical framework and hypothesized relationships; however, its contribution to the prediction of social responsibility should be interpreted with caution.

Three hypotheses were put forth and examined as a result of the empirical research that was performed. It was determined whether the index variables were significantly linearly connected using basic linear regression analysis and Pearson correlations. The research findings were validated using correlation analysis, which revealed the direction and intensity of the linear relationship between variables, and simple linear regression analysis, which calculated parameters from linear equations to predict the values of one variable depending on the other.

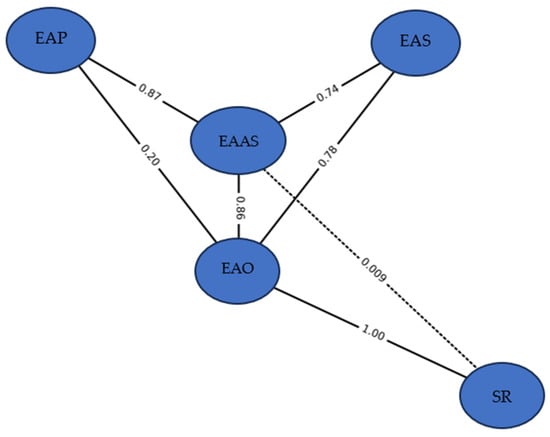

The proposed model was tested using a structural equation model (SEM), integrating ethical attitudes at the political (AEP), social (EAS), agricultural sectoral (EAAS), organizational (EAO), and social responsibility (SR) levels within organizations active in the agricultural field in Romania. The results confirmed most of the initial hypotheses, outlining a complex and coherent picture of the influence of ethics on socially responsible behavior.

The proposed structural model (SEM) highlights the relationships between ethical attitudes at the political (AEP), social (EAS), agricultural sectoral (EAAS), and organizational (EAO) levels and social responsibility (SR) (Figure 3). The arrows indicate the direction of influence, and the coefficients represent the standardized values (β), obtained through multiple regression analysis. The model validates hypotheses H1–H3, revealing a strong influence of sectoral ethics on social responsibility (β = 0.88) and a significant contribution of social ethics on the organizational environment (β = 0.78). Although the literature suggests a direct relationship between sectoral ethics agricultural (EAAS) and social responsibility [28,29], in the current model, this link was not statistically significant (β = 0.09, p > 0.05). This result can be explained by the overlap of values already explained by organizational ethics (EAO), which indicates a possible collinearity or insufficient differentiation between perceptions of organizational and sectoral ethics. Despite this statistical insignificance, the EAAS to SR path was retained in the model to maintain theoretical coherence and reflect the hypothesized relationships; however, this finding should be interpreted cautiously and considered a potential area for refinement in future studies.

Figure 3.

SEM model—relationships between ethical attitudes and social responsibility in the Romanian agricultural field.

The proposed SEM model was evaluated using an extensive set of adjustment indicators. Table 6 presents the obtained values, which fell within the limits accepted by the specialized literature [36,37]. Values such as CFI = 0.974 and RMSEA = 0.045 indicate an excellent fit between the theoretical model and the empirical data. Thus, the validated model provides a coherent framework for understanding the relationships between ethical attitudes and social responsibility in the Romanian agricultural sector. The analysis carried out using the SEM model contributes significantly to the understanding of the structural relationships between political, social, sectoral, and organizational ethical attitudes and how they influence social responsibility (SR) behaviors in the Romanian agricultural sector. From the perspective of economic statistics, the application of the SEM method in this context offers an integrated and robust approach to quantifying interdependent influences, going beyond the limits of simple correlations or classical regressions.

Table 6.

Centralization of the results obtained.

The relevance of this analysis derives from its complexity and granularity, providing not only the confirmation of hypothetical links but also the simultaneous evaluation of multiple decision-making levels (political, social, sectoral, and organizational). In a context in which the local literature on ethics and social responsibility in agriculture is fragmentary or limited to descriptive studies, this research makes a substantial methodological and empirical contribution.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to assess the impacts of political, social, and organizational ethical attitudes on agricultural sector practices. One notable borderline finding emerged from the SEM analysis, where the path coefficient between sectoral ethical attitudes (EAAS) and social responsibility (SR) was not statistically significant (β = 0.09, p > 0.05). This suggested that the influence of sectoral ethics on CSR practices may be mediated or confounded by strong organizational ethical attitudes (EAO), as evidenced by the robust positive relationship between EAO and SR (β = 0.88, p < 0.001). This result highlights a potential collinearity between sectoral and organizational ethics, where respondents may not clearly differentiate between the ethical practices of their individual organizations and those prevalent in the broader sector. It also suggests that in the Romanian context, companies’ CSR practices are more directly shaped by internal organizational norms and values than by sector-wide ethical expectations. Recent studies on the application of advanced technologies such as gene transfer and nanotechnology emphasize the need for an ethical approach [40,41]. The use of nanotechnology in agriculture, for example, raises issues of labeling and possible adverse effects on the environment and public health, adding weight to the idea that ethical values must be actively integrated into modern agricultural processes. The Romanian agricultural sector faces additional challenges related to transparency, public trust, and regulatory compliance, making ethical considerations even more critical. Ignaciuk (2015) also explores the multiple challenges in adapting agriculture to climate change, addressing not only the economic and political aspects but also the social and ethical implications, which are essential for global food security [42], a lesson particularly relevant for Romania given its exposure to climate vulnerabilities and its evolving institutional frameworks. Choudhary and Sharma (2024) discuss the importance of ethical considerations in public policy, stressing that an ethical approach is essential for the sustainable development of agriculture, especially in ecologically sensitive contexts [43].

The regression analysis applied to the second hypothesis confirmed the significant impact of ethical attitudes at the sectoral level on organizational ethics. Consumer studies of upcycled food products and ethical certification of tropical products show an increased demand for responsible and sustainable agricultural practices [44], in Romania, the adoption of such practices can be hindered by limited awareness, resource constraints, and varying levels of management commitment. This suggests that fostering ethical climates within organizations requires not only compliance but also proactive engagement with stakeholders, tailored to the specific socio-cultural environment. These data reflect that organizational ethics are becoming a decisive factor in consumer choice, leading organizations to adopt practices that promote transparency and responsibility toward the environment and community. A similar study on how to realize an econometric model shows that European agricultural policies are an essential building block for achieving sustainability objectives, aiming to reduce negative environmental impacts, maintain the economic competitiveness of the agricultural sector, and promote balanced rural development [45]. Kadic-Maglajlic et al. (2019) found that business ethical climate and salesperson moral equity are positively associated with salesperson customer orientation [10]. Furthermore, industrial and organizational ethical norms have a more robust joint effect on customer orientation than either ethical climate alone [10]. By integrating technological, socioeconomic, and environmental factors into a cohesive policy framework, governments can boost productivity while ensuring economic viability and environmental sustainability [46].

To further explore the impact of social responsibility, the third hypothesis used regression models and correlation coefficients, confirming a deep connection between social responsibility and ethical attitudes. This result agreed with studies on the life cycle of products in Latin America, where social assessments indicate the need for strict standards for animal welfare and combating agricultural crimes [47]. Also, the study on green biotechnology suggests that emerging technologies in agriculture can only be effectively integrated through an ethical and sustainable approach. In the same context, ref. [48] addressed the interdependence between the right to food and sustainable agricultural practices, emphasizing that a holistic transformation is necessary to balance ethics and sustainability. Another important study carried out in this field by Nugraha et al. (2024) shows a positive and significant relationship between psychological factors (attitudes, norms, and perceived control) and farmers’ intentions to adopt sustainable practices [49]. Farmers with positive perceptions of sustainability are more inclined to adopt such practices. Similar concerns are echoed in neighboring Bulgaria, where the integration of community-supported agriculture (CSA) and organic production has been recognized as a strategy for enhancing sustainable rural development. Terziev and Arabska (2016) emphasize the role of corporate social responsibility in small-scale farming models, highlighting that community motivation, transparency, and feedback mechanisms are essential for ethical agricultural development [50]. Their proposed model for CSA groups aligns with the multilevel ethical framework considered in the present study, reinforcing the importance of localized, culturally adaptive approaches in fostering sustainability and public trust [50]. In Hungary, Győri et al. (2021) conclude that agribusinesses are increasingly adopting CSR strategies aimed at climate adaptation and mitigation, reinforcing our argument that ethical organizational attitudes are essential for sustainable practices [51]. A comparative study conducted in Romania and Hungary shows that the process of forming an organizational culture in which social responsibility occupies a priority place is still in its early stages. At this stage, employees are aware of the importance of elements such as organizational identity, shared values, strategic directions, and the relationship with the community. However, transforming these awarenesses into concrete attitudes and internalizing values takes time [52]. Only through this process can social responsibility become an essential component of organizational culture. Awareness of environmental aspects proves to be an essential mediator between the ethical behavior of farmers and the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices. All these findings support the idea that ethical attitudes, both at the political and social level and at the organizational level, are essential for integrating sustainability principles in a way that respects society’s values. From a theoretical perspective, this study contributes to the literature by integrating ethical, political, and social dimensions into the analysis of agribusiness practices, with a focus on an emerging economy context. Although the employed methodology—a structured questionnaire and quantitative analysis—may not represent a radical innovation, it provides empirical evidence from Romania, a context often underrepresented in SR research. Future studies should consider mixed-method approaches, incorporating qualitative data to capture the depth of ethical attitudes and the socio-cultural dynamics influencing them.

Furthermore, the study’s emphasis on the interconnectedness of ethical attitudes across multiple societal levels—from political and social to organizational and sectoral—represents an original theoretical contribution. This multilevel perspective acknowledges that in Romania, ethical practices are not merely driven by internal corporate values but are also influenced by broader cultural norms, regional disparities, and evolving regulatory landscapes. By situating the analysis within the unique socio-economic and historical context of Romania, this study adds a critical dimension to the broader understanding of how CSR and ethical governance manifest differently across EU member states.

6. Conclusions

The findings of this study confirmed that in the Romanian agricultural sector, organizational ethics and social responsibility were closely interlinked, with robust internal ethical frameworks enhancing SR practices.

This research demonstrated, from an empirical perspective, that organizational ethics were a key driver of socially responsible behavior in the Romanian agribusiness context. The validated SEM model illustrated how external influences (political and social ethics) and internal factors (sectoral and organizational ethics) converged to shape CSR practices. Notably, the path from sectoral ethics to social responsibility was not statistically significant, suggesting a potential collinearity with organizational ethics and highlighting the need for future refinement of the model. This research not only validated the formulated hypotheses but also confirmed the applicability of advanced quantitative models in less explored fields, such as agriculture, laying the foundations for a new direction of analysis in the Romanian economic literature. Legislation, financial regulations, other government practices, supply chains, pricing, and transparent procedures overseen by internal and external supervisors are all necessary for agricultural sector companies to be able to offer equal opportunities to all, provide safe working conditions, have fair compensation and rewards policies, and create diversity and discrimination policies. They must also be more aware of environmental protection, waste recycling, energy and water consumption, emissions, technical resources, and the use of nature. Integrating organizational and social ethics within the same policy program requires more than the good intentions of a manager or a shareholder. Maintaining social ethics is a continuous and extremely difficult endeavor. To sum up, our research suggests that a morally grounded strategy can help the shift to more conscientious farming methods, which could enhance the interaction between the community, industry, and the environment.

Although this study makes significant contributions to the understanding of sustainable behaviors in agriculture, it presents several limitations inherent in the questionnaire-based research method that future research could address. The limitations of this study include potential sectoral heterogeneity within the sample (as it includes agriculture, forestry, and fishing enterprises) and the reliance on self-reported data from a questionnaire, which may introduce response bias. The model, while statistically robust, may also be influenced by unmeasured confounding variables and lacks confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and measurement invariance testing, which future research should address.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.-M.P., M.-C.D. and A.D.; methodology, D.-M.P., M.-C.D., A.D. and G.S.; software, G.S. and N.-M.D.; validation, N.-M.D., A.D. and C.-M.V.; formal analysis, D.-M.P., M.-C.D. and N.-M.D.; investigation, A.D. and C.-M.V.; resources, D.-M.P.; data curation, D.-M.P. and A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, D.-M.P., M.-C.D., A.D., C.-M.V. and G.S.; writing—review and editing, D.-M.P., M.-C.D., A.D. and C.-M.V.; supervision, D.-M.P. and M.-C.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to Legal Regulations (According to the requirements of Regulation (EU) 2016/679 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation) and Law No. 506/2004 on the processing of personal data and the protection of privacy, the research team is obliged to manage the data you will provide in secure conditions and only for the specified purposes: socio-demographic data and questionnaire responses).

Informed Consent Statement

Study participants were informed about the collection of responses to this research. They provided their consent, understanding that the responses would be processed statistically and that no personal data would be collected.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EAAS | Ethical attitudes at the agricultural sector level |

| EAP | Ethical attitudes at the political level |

| EAS | Ethical attitudes at the social level |

| EAO | Ethical attitudes at the organizational level |

| SR | Social responsibility |

| SEM | Structural equation model |

| CFI | Comparative fit index |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis index |

| RMSE | Root mean square error of approximation |

| SRMR | Standardized root mean square residual |

References

- Pandey, D.K.; Mishra, R. Towards sustainable agriculture: Harnessing AI for global food security. Artif. Intell. Agric. 2024, 12, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achudhan, S.; Chinnadurai, M.; Anjugam, M. Perceptual Structure of Crop Variegation in Tamil Nadu—A Methodological Approach. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2018, 7, 1602–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergner, I.; Lippert, C. On the effects that motivate pesticide use in perspective of designing a cropping system without pesticides but with mineral fertilizer—A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 43, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ema, N.; Mithu, M.; Sayem, A. Exploring driving factors in employing waste reduction tools to alleviate the global food security and sustainability. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Bilali, H.; Strassner, C.; Ben Hassen, T. Sustainable agri-food systems: Environment, economy, society, and policy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciornei, L.; Udrea, L.; Munteanu, P.; Simion, P.-S.; Petcu, V. The Effects of Climate Change. Trends Regarding the Evolution of Temperature in Romania. Ann. Valahia Univ. Târgovişte Agric. 2023, 15, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, K. Family farming in climate change: Strategies for resilient and sustainable food systems. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlberg, L. The Claim to Moral Adequacy of a Highest Stage of Moral Judgment. J. Philos. 1973, 70, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, M.; Dalton, D.R.; Hill, J.W. The Organization of Ethics and the Ethics of Organizations: The Case for Expanded Organizational Ethics Audits. Bus. Ethics Q. 1993, 3, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadic-Maglajlic, S.; Micevski, M.; Lee, N.; Boso, N.; Vida, I. Three Levels of Ethical Influences on Selling Behavior and Performance: Synergies and Tensions. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 156, 377–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro, V.; Arias, J.; Dürr, J.; Elverdin, P.; Ibáñez, A.M.; Kinengyere, A.; Opazo, C.M.; Owoo, N.; Page, J.R.; Prager, S.D.; et al. A scoping review on incentives for adoption of sustainable agricultural practices and their outcomes. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P. Agricultural sustainability: What it is and what it is not. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2007, 5, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerro, M.; Raimondo, M.; Stanco, M.; Nazzaro, C.; Marotta, G. Cause Related Marketing among Millennial Consumers: The Role of Trust and Loyalty in the Food Industry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, S.R.; Isabella, G.; Boaventura, J.M.G.; Mazzon, J.A. The influence of corporate social responsibility on employee satisfaction. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 2325–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñalver, A.J.B.; Conesa, J.A.B.; Nieto, C.d.N. Analysis of Corporate Social Responsibility in Spanish Agribusiness and Its Influence on Innovation and Performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J. Agricultural sustainability: Concepts, principles and evidence. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2007, 363, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, M.S.; Attanda, M.L. The Concept Sustainable Agriculture: Challenges and Prospects. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2013, 53, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesseler, J. The EU’s farm-to-fork strategy: An assessment from the perspective of agricultural economics. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2022, 44, 1826–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beldman, A.; Pishgar-Komleh, S.H.; Termeer, E. Mitigation Options to Reduce GHG Emissions at Dairy and Beef Farms: Results from a Literature Review and Survey on Mitigation Options Currently Being Used Within the Network of the Sustainable Agriculture Initiative Platform (SAI Platform); Wageningen Economic Research: Wageningen, The Netherland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Toft, K.H.; Rendtorff, J.D. Corporate Social Responsibility in Denmark. In Current Global Practices of Corporate Social Responsibility: In the Era of Sustainable Development Goals; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 79–97. ISBN 978-3-030-68386-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kochukrishna Kurup, V.S.; Rangasami, P.; Pillai, S.S. Enhancing Agricultural development in rural Indian communities: The contribution of NGOs through Corporate Social Responsibility Initiatives. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Conference on Technologies for Sustainability (SusTech), Portland, OR, USA, 14–17 April 2024; pp. 273–280. [Google Scholar]

- De Luca, R.; Sessa, M.R.; Esposito, B.; Malandrino, O. How certified benefit corporations contribute to corporate social responsibility disclosure: Empirical evidence from Italy. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 1668–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Adli, D.N.; Nugraha, W.S.; Yudhistira, B.; Lavrentev, F.V.; Shityakov, S.; Feng, X.; Nagdalian, A.; Ibrahim, S.A. Social, ethical, environmental, economic and technological aspects of rabbit meat production—A critical review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, M. Corporate social responsibility in the food sector. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2011, 38, 297–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD-FAO Guidance for Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains; OECD: Paris, France, 2016; ISBN 978-92-64-25095-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Agriculture and the Environment; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/sub-issues/agriculture-and-environment.html (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Topor, D.I.; Ionescu, C.A.; Fülöp, M.T.; Căpușneanu, S.; Stanescu, S.G.; Breaz, T.O.; Voinea, C.M.; Moldovan, I.A. Factors that influence bank loans for agriculture in Romania. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2023, 8, 2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elford, A.C.; Daub, C.-H. Solutions for SMEs Challenged by CSR: A Multiple Cases Approach in the Food Industry within the DACH-Region. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiandrino, S.; Busso, D.; Vrontis, D. Sustainable responsible conduct beyond the boundaries of compliance: Lessons from Italian listed food and beverage companies. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 1035–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaeshi, K.; Osuji, O.; Nnodim, P. Corporate Social Responsibility in Supply Chains of Global Brands: A Boundaryless Responsibility? Clarifications, Exceptions and Implications. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, L. Corporate and consumer social responsibility in the food supply chain. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissinger, G. Corporate Social Responsibility and Supply Agreements in the Private Sector: Decreasing Land and Climate Pressures; CCAFS Working Paper 14; CCAFS: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pucci, T.; Casprini, E.; Galati, A.; Zanni, L. The virtuous cycle of stakeholder engagement in developing a sustainability culture: Salcheto winery. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 119, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, A.; Toporowski, W. CSR failures in food supply chains—An agency perspective. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktar, I. Disclosure strategies regarding ethically questionable business practices. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 162–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-1-4625-5191-0. [Google Scholar]

- Cudeck, R. 10—Exploratory Factor Analysis. In Handbook of Applied Multivariate Statistics and Mathematical Modeling; Tinsley, H.E.A., Brown, S.D., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 265–296. ISBN 978-0-12-691360-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, L.K.; Chandel, A. Ethical and Regulatory Perspective on Nanotechnology in Agriculture. Just Agric. Multidiscip. E-Newsl. 2024, 5, 94–104. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, A.M.; Singh, L. Horizontal gene transfer in plant biotechnology: Mechanisms and applications. Int. J. Res. Agron. 2024, 7, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignaciuk, A. Adapting Agriculture to Climate Change: A Role for Public Policies; OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers; OECD: Paris, France, 2015; Volume 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.; Sharma, A. Exploring the Role of Environmental Ethical Consideration in Advancing Green Growth: Perspectives from India. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Sociol. 2024, 42, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-S.; Tsai, T.-Y.; Lai, K.-L.; Chen, H.-S. Analyzing Consumer Motivations and Behaviors Towards Upcycled Food from an Environmental Sustainability Perspective. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, L.; Bărbuţă-Mişu, N.; Zlati, M.; Fortea, C.; Antohi, V. Quantifying the Performance of European Agriculture Through the New European Sustainability Model. Agriculture 2025, 15, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Wang, X. The Impact of Technological Innovations on Agricultural Productivity and Environmental Sustainability in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Huerta, A.; Padilla-Rivera, A.; Galindo, F.; González-Rebeles, C.; Güereca, L.P. Social life cycle assessment of calves in Mexico and identification of barriers in the use of a generic database. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2025, 30, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Tyagi, P.K.; Tyagi, S.; Ghorbanpour, M. Integrating green nanotechnology with sustainable development goals: A pathway to sustainable innovation. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugraha, R.; Muhaimin, A.W.; Maulidah, S. Sustainable Production Behavior Model of Hybrid Corn Farmers: A Case Study in Indonesia. Nongye Jixie Xuebao Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2024, 55, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terziev, V.; Arabska, E. Sustainable rural development through organic production and community-supported agriculture in Bulgaria. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2016, 22, 527–535. [Google Scholar]

- Győri, Z.; Madarasiné Szirmai, A.; Csillag, S.; Bánhegyi, M. Corporate Social Responsibility in Hungary: The Current State of CSR in Hungary. In Current Global Practices of Corporate Social Responsibility: In the Era of Sustainable Development Goals; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 193–211. [Google Scholar]

- Hatos, A.; Ştefănescu, F. Social Reponsibility Attitudes and Practices of Companies: Hungary vs. Romania Crossborder Comparison. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2017, 13, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).