Does Public Transport Planning Consider Mobility of Care? A Critical Policy Review of Toronto, Canada

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

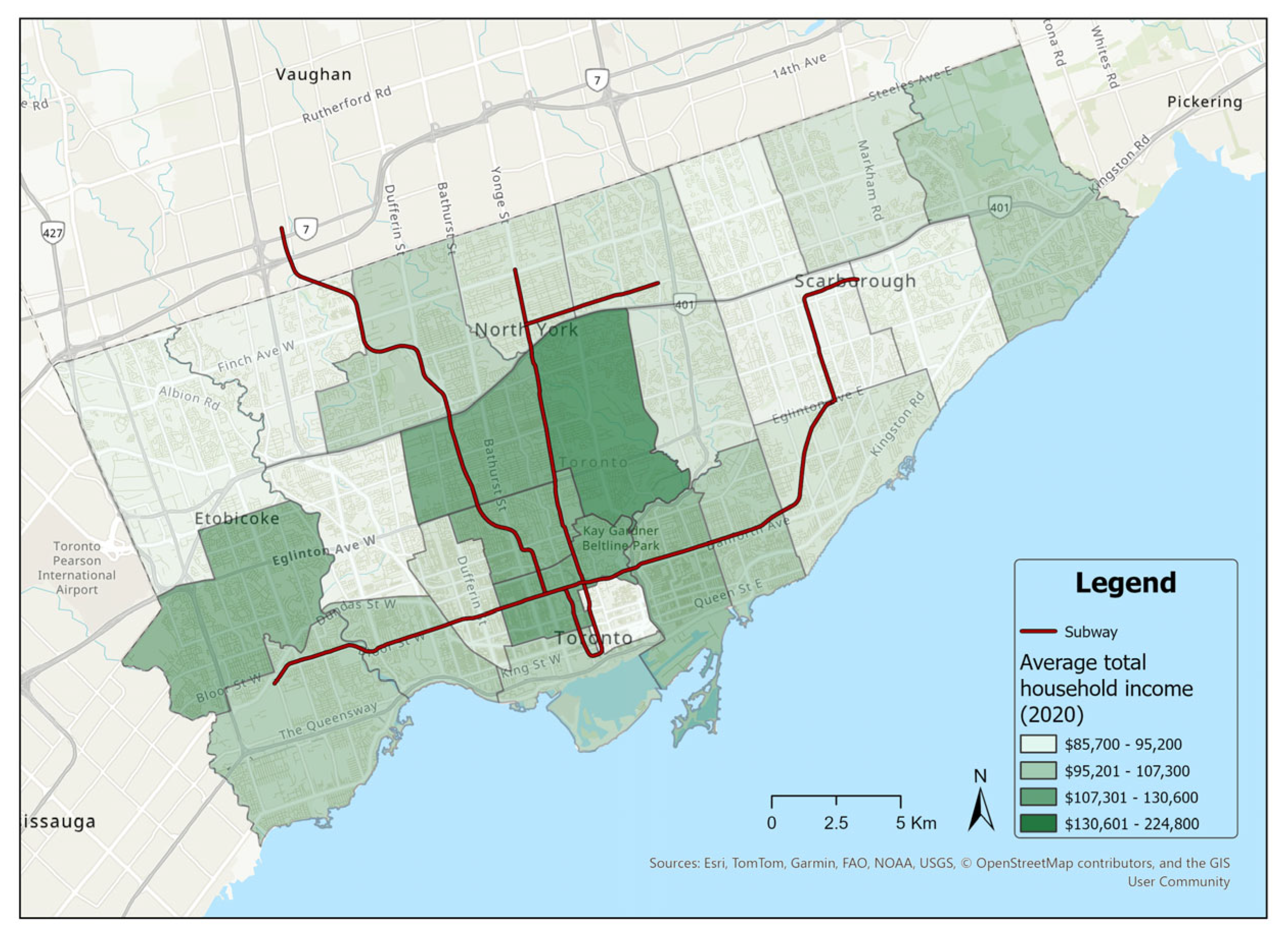

3.1. Context

3.2. Search Strategy

3.3. Analysis

4. Results

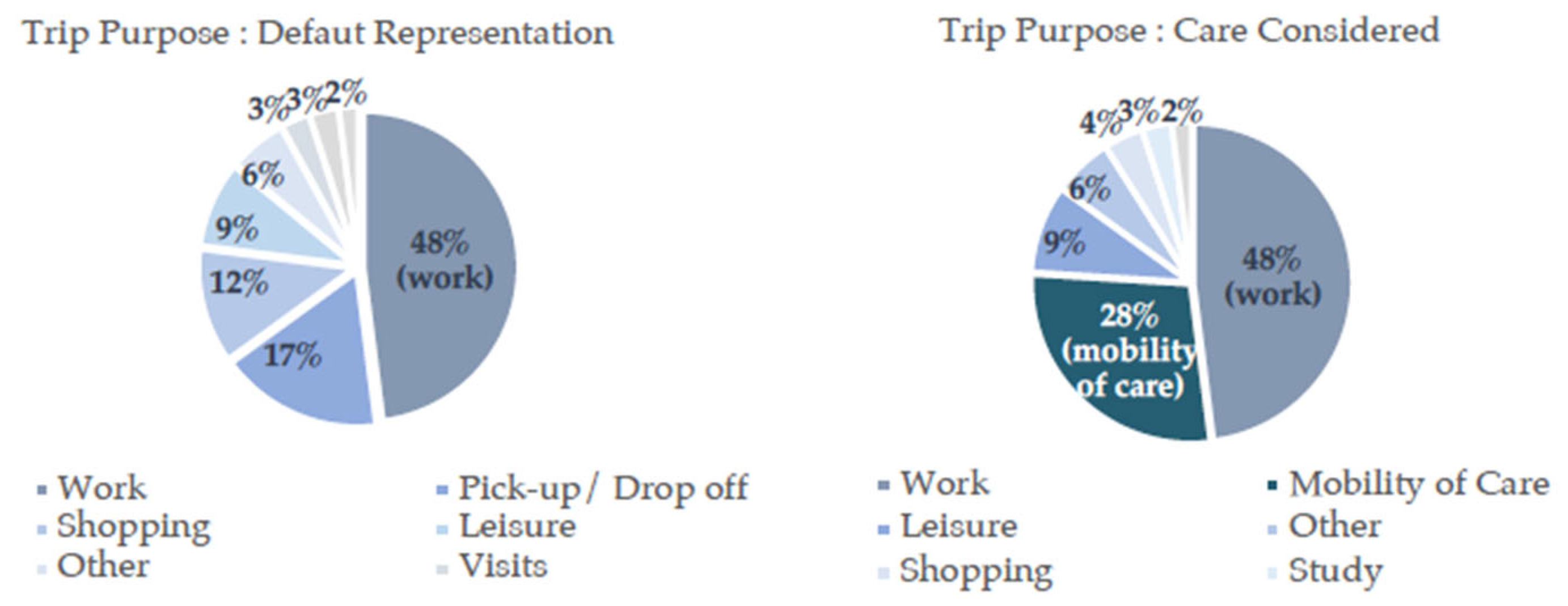

4.1. Emphasis on Employment Trips

4.2. Where Mobility of Care Is Considered

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- Measure Care Directly

- First Steps to Facilitate Mobility of Care Travel by Public Transport

- Include Residents in Transit Planning

- Planning Transit for Mobility of Care Goes Beyond Transit Planning

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grant-Smith, D.; Osborne, N.; Johnson, L. Managing the challenges of combining mobilities of care and commuting: An Australian perspective. Community Work Fam. 2016, 2, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemiatycki, M.; Enright, T.; Valverde, M. The gendered production of infrastructure. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2020, 44, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, C.; Joelsson, T. Integrating Gender into Transport Planning: From One to Many Tracks; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez de Madariaga, I. Mobility of Care: Introducing New Concepts in Urban Transport. In Fair Shared Cities: The Impact of Gender Planning in Europe; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez de Madariaga, I. Vivienda, movilidad y urbanismo para la igualdad en la diversidad: Ciudades, género y dependencia. Ciudad. Territ. 2009, XLI, 581–598. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez de Madariaga, I. Housing, mobility and planning for equality in diversity: Cities, gender and dependence. In Social Housing and City, Edición Especial en Inglés de Ciudad y Territorio; Estudios territoriales XLI, 162; Ministerio de Vivienda: San Salvador, El Salvador, 2010; pp. 177–197. [Google Scholar]

- Ravensbergen, L.; Fournier, J.; El-Geniedy, A. Exploratory Analysis of Mobility of Care in Montreal, Canada. Transp. Res. Rec. 2022, 2677, 1499–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez de Madariaga, I.; Zucchini, E. Measuring Mobilities of Care, a Challenge for Transport Agendas. In Integrating Gender into Transport Planning; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Murillo-Munar, J.; Gómez-Varo, I.; Marquet, O. Caregivers on the move: Gender and socioeconomic status in the care mobility in Bogotá. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2023, 21, 100884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Varo, I.; Delclòs-Alió, X.; Miralles-Guasch, C.; Marquet, O. Accounting for care in everyday mobility: An exploration of care-related trips and their sociospatial correlates. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2024, 106, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazia, C.; Campisi, T.; Bellamacina, D.; Catania, G.F.G. Urban and Social Policies: Gender Gap for the Borderless Cities. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications, Athens, Greece, 3–6 July 2023; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Palm, M. Rethinking ‘discretionary’ travel: The impact of night and evening shift work on social exclusion and mobilities of care. Travel Behav. Soc. 2025, 40, 101030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardno, C. Policy Document Analysis: A Practical Educational Leadership Tool and a Qualitative Research Method. Educ. Adm. Theory Pract. 2018, 24, 623–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARTM. Autorité Régional de Transport Métropolitain: Enquête Origine-Destination 2018. 2022. Available online: https://www.artm.quebec/planification/enqueteod/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- TTS. Transportation Tomorrow Survey. Available online: http://www.transportationtomorrow.on.ca (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Hanson, S. Gender and mobility: New approaches for informing sustainability. Gend. Place Cult. 2010, 17, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primerano, F.; Taylor, M.; Pitaksringkarn, L.; Tisato, P. Defining and understanding trip chaining behaviour. Transportation 2008, 35, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheiner, J.; Holz-Rau, C. Women’s complex daily lives: A gendered look at trip chaining and activity pattern entropy in Germany. Transportation 2017, 44, 117–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejewska, M.; Miralles-Guasch, C. “I have children and thus I drive”: Perceptions and Motivations of Modal Choice Among Suburban Commuting Mothers. Finisterra 2019, 54, 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ravensbergen, L.; Buliung, R.; Sersli, S. Vélomobilities of care in a low-cycling city. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 134, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City of Toronto. Toronto at a Glance. July 2024. Available online: https://www.toronto.ca/city-government/data-research-maps/toronto-at-a-glance/ (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Toronto Transit Commission. 5-Year Service and Customer Experience Action Plan 2024–2028. Available online: https://www.ttc.ca/about-the-ttc/projects-and-plans/5-Year-Service-Plan-and-10-Year-Outlook (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- City of Toronto. 2021 Ward Profiles. 2021. Available online: https://open.toronto.ca/dataset/ward-profiles-25-ward-model/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Metrolinx. Eglington Crosstown LRT. July 2024. Available online: https://www.metrolinx.com/en/projects-and-programs/eglinton-crosstown-lrt (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Metrolinx. Finch West LRT. Available online: https://www.metrolinx.com/en/projects-and-programs/finch-west-lrt/what-were-building (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Toronto Transit Commission. Sustaining a Reliable Transit System: Outlook 2024 and Beyond. Available online: https://cdn.ttc.ca/-/media/Project/TTC/DevProto/Documents/Home/Public-Meetings/Board/2023/June-12/4_Sustaining_a_Reliable_Transit_System_Outlook_2024_and_Beyond.pdf?rev=61c6b26482974a958de7ec9f71b4009b&hash=B40A02964F09631B90874D51D02EE682#:~:text=The%20TTC%20will%20be%20bringing,Service%20Plan%20in%20early%202024 (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- City of Toronto. City Wards. 2025. Available online: https://open.toronto.ca/dataset/city-wards/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- City of Toronto. TTC Subway Shapefiles. 2025. Available online: https://open.toronto.ca/dataset/ttc-subway-shapefiles/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- City of Toronto. TTC Routes and Schedules. 2025. Available online: https://open.toronto.ca/dataset/ttc-routes-and-schedules/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Grisé, E.; Boisjoly, G.; Babbar, P.; Peace, J.; Cooper, D. Understanding and Responding to the Transit Needs of Women in Canada; Leading Mobility, University of Edmonton, and Polytechnique Montréal: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Weate, P. Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toronto Transit Commission. Toronto Transit Commission Service Standards and Decision Rules for Planning Transit Service. Available online: https://cdn.ttc.ca/-/media/Project/TTC/DevProto/Documents/Home/About-the-TTC/Projects-Landing-Page/Transit-Planning/Service-Standards_May-2024.pdf?rev=8573d381d7294e58920a8178cacc2c9f (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Toronto Transit Commission. 2022 Annual Service Plan. Available online: https://cdn.ttc.ca/-/media/Project/TTC/DevProto/Documents/Home/About-the-TTC/5_year_plan_10_year_outlook/2023/2022-ASP/Final-2022-ASP.pdf?rev=36e060e2c699411390caf9ce2370d5b5&hash=1D04C8B064BFD2A79A0BD99C97B20522 (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Toronto Transit Commission. Making Headway Update to the TTC Capital Investment Plan 2022–2036. Available online: https://pw.ttc.ca/-/media/Project/TTC/DevProto/Documents/Home/Transparency-and-accountability/Reports/TTC_CIP_June15x-id_2022-04-13-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Toronto Transit Commission. Advancing the 5-Year Fare Policy. Available online: https://cdn.ttc.ca/-/media/Project/TTC/DevProto/Documents/Home/Public-Meetings/Board/2022/February-10/Reports/10_Advancing_the_5-Year_Fare_-Policy.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Toronto Transit Commission. Accessibility Plan Status Update. Available online: https://cdn.ttc.ca/-/media/Project/TTC/DevProto/Documents/Home/Public-Meetings/Board/2022/June-23/11_2022_Accessibility_Plan_Status_Update.pdf?rev=254851cd4e8b48bc9a27b113a5df8143&hash=FC3C4F236F861B127A719D4E2C017859 (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Toronto Transit Commission. 2019–2023 TTC Multi-Year Accessibility Plan. Available online: https://cdn.ttc.ca/-/media/Project/TTC/DevProto/Documents/Home/Public-Meetings/Board/2019/May_8/Reports/6_2019-2023_TTC_Multiyear_Accessibility_Plan.pdf?rev=b5282cd84d6d4e4f85a1b155fe827a63&hash=935F56934B77FB8B3253A4A2FB5193DC (accessed on 3 June 2024).

| Areas | Questions | |

|---|---|---|

| Document Production and Location |

| |

| Authorship and Audience |

| |

| Policy Context |

| |

| Policy Text |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| ||

| Policy Consequence |

| |

| Document | Title | Author | Year | # of Pages | Policy Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service Standards [33] | Toronto Transit Commission Service Standards and Decision Rules for Planning Transit Service | Toronto Transit Commission | 2024 | 40 | To lay the framework for achieving the TTC’s goals of making public transit the fastest most cost-efficient way to travel and for planning, monitoring, adjusting, and evaluating transit services throughout the City of Toronto (p. 4) |

| 2022 ASP [34] | 2022 Annual Service Plan | Toronto Transit Commission Chief Strategy and Customer Officer (Acting) | 2022 | 80 | To provide a blueprint for transit service in Toronto for 2022 and advances actions identified in the 2020–2024 5-Year Service Plan (p. 1) |

| 2024–2028 5YSP [22] | 5-Year Service and Customer Experience Action Plan 2024–2028 | Toronto Transit Commission Chief Strategy and Customer Experience Officer | 2024 | 202 | To provide a blueprint for service and customer experience initiatives to be implemented throughout 2024–2028, ensuring these proposals address immediate needs and the City’s overall goals (p. 2, 9) |

| CIP 2022–2036 [35] | Making Headway Update to the TTC Capital Investment Plan 2022–2036 | Toronto Transit Commission | 2022 | 54 | To update the TTC’s initial CIP, released in 2019, identify the most immediate unfunded priorities, and refine cost projections for capital investment over the next 15 years (p. 11) |

| Fare Policy [36] | Advancing the 5-Year Fare Policy | Toronto Transit Commission Chief Strategy and Customer Officer (Acting) | 2022 | 18 | To provide an update on the progress of developing the TTC’s 5-Year Fare Policy by summarizing the analysis of fare options for further consideration and findings from public consultation (p. 1) |

| Reliable Transit System [26] | Sustaining a Reliable Transit System: Outlook 2024 and Beyond | Toronto Transit Commission Chief Executive Officer | 2023 | 24 | To outline the key challenges and trends facing the TTC in 2024 and beyond and to inform strategic directions in the TTC’s next 5-Year Corporate Plan, the 2024 Annual Service Plan and the 2024 Operating and Capital Budget Process (p. 2, 5) |

| 2022 AP Update [37] | 2022 Accessibility Plan Status Update | Toronto Transit Commission Chief Strategy and Customer Officer (Acting) | 2022 | 17 | To provide an update on the progress made towards achieving the 52 (now 47) initiatives outlined in the 2019–2023 TTC Multi-Year Accessibility Plan |

| Total | Service Standards | 2022 ASP | 2024–2028 5YSP | CIP 2022–2036 | Fare Policy | Reliable Transit System | 2022 AP Update | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Destinations | ||||||||

| Grocery | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Health 1 | 13 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Escorting | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Errand | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shopping | 10 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Total care destinations | 29 | 7 | 7 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Employment | 57 | 5 | 13 | 24 | 3 | 0 | 12 | 0 |

| Care Trip Characteristics | ||||||||

| Strollers | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Groceries | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Trip chaining | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Children | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Youth 2 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Seniors | 16 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 2 |

| People with disabilities 3 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Women | 13 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Smith, R.; Jain, P.; Grisé, E.; Boisjoly, G.; Ravensbergen, L. Does Public Transport Planning Consider Mobility of Care? A Critical Policy Review of Toronto, Canada. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5466. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125466

Smith R, Jain P, Grisé E, Boisjoly G, Ravensbergen L. Does Public Transport Planning Consider Mobility of Care? A Critical Policy Review of Toronto, Canada. Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5466. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125466

Chicago/Turabian StyleSmith, Rebecca, Poorva Jain, Emily Grisé, Geneviève Boisjoly, and Léa Ravensbergen. 2025. "Does Public Transport Planning Consider Mobility of Care? A Critical Policy Review of Toronto, Canada" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5466. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125466

APA StyleSmith, R., Jain, P., Grisé, E., Boisjoly, G., & Ravensbergen, L. (2025). Does Public Transport Planning Consider Mobility of Care? A Critical Policy Review of Toronto, Canada. Sustainability, 17(12), 5466. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125466