Strengthening of the Rural Community and Corn Food Chain Through the Application of the WWP Model and the Integration of CFS-RAI Principles in Puebla, México

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Intervention Territory

1.2. Criteria for Case Selection

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

2.1.1. The WWP Model, PRIAs and Food Systems

2.1.2. Agri-Food Chain Models

3. Results

3.1. Case 1: Agri-Food Chain Maize-Bean Guide Bean Association

3.1.1. Relationship of the Family Unit to the CFS-RAI Principle

3.1.2. Characteristics of the Family Production Unit (FPU)

3.1.3. Production, a Component of the Corn–Bean and Ayocote Agri-Food Chain

3.1.4. Processing, Transformation

3.1.5. Commercialization, Marketing

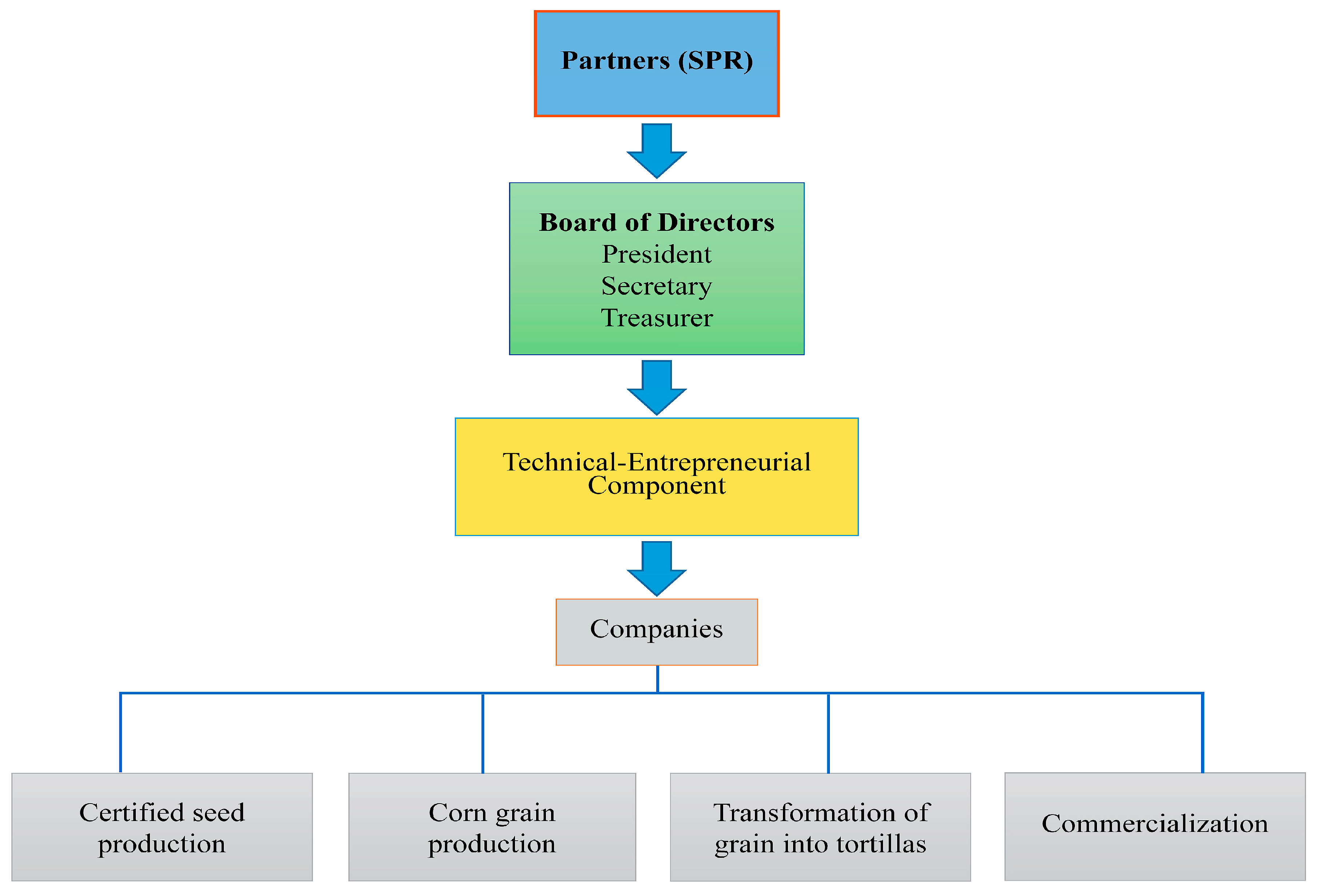

3.2. Case 2: Corn Agri-Food Chain and Its Transformation into Tortillas Through a Rural Production Society

3.2.1. Personal Characteristics of the Members of the Association

3.2.2. Production, Transformation and Commercialization as Elements of the Maize Agri-Food Chain of the Campo Lima Society and Its Relationship to the CFS-RIA Principles

3.2.3. Seed Production and Commercial Plantings

3.2.4. Transformation and Commercialization

3.3. Case 3: Agri-Food Chain of Maize Produced at the Family Level but Transformed and Marketed Through a Cooperative

3.3.1. Relationship of the Cooperative’s Activities with the CFS-RIA

3.3.2. Production

3.3.3. Transformation

3.3.4. Commercialization

3.4. Relationship Between the Application of the CFS-RIA Principles and Agri-Food Models

3.5. Relationship of the Application of the Working with People Model in Each Agri-Food Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía, Estadística e Informática, INEGI. Resultados Oportunos del Censo Agropecuario 2022 Puebla, Boletín de Comunicado de Prensa; INEGI: Aguascalientes, México, 2023; pp. 1–2.

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía, Estadística e Informática, INEGI. Resultados Oportunos del Censo Agropecuario 2022 Puebla, Presentación; INEGI: Aguascalientes, México, 2023; pp. 13–30.

- Regalado, J.; Pérez-Ramírez, N.; Ramírez Juárez, J.; Méndez Espinoza, J.A. Los Grupos de Acción y La Aplicación de Tecnología de Alta Productividad Para Maíz de Secano En Localidades Del Plan Puebla, México. La Granja 2021, 34, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Carmenado, I.D.L.; Becerril-Hernández, H.; Rivera, M. La agricultura ecológica y su influencia en la prosperidad rural: Visión desde una sociedad agraria (Murcia, España). Agrociencia 2016, 50, 375–389. [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla, A.; de los Ríos, I.; Salvo, M. Working With People (WWP) in Rural Development Projects: A Proposal from Social Learning. Cuad. De Desarro. Rural 2013, 10, 131–157. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, H.E. El concepto de “institución”: Usos y tendencias. Rev. De Estud. Políticos 1962, 1, 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- MacIver, R.M.; Page, C.H. Society: An Introductory Analysis, 1957th ed.; Macmillan & Co Ltd.: London, UK, 1949; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, G.M. ¿Qué son las instituciones? Rev.CS 2011, 8, 17–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niño Velásquez, E.; Regalado López, J.; Hernández González, T. La Asociación Campesina Independiente y Sus Relaciones Con El Estado e Instituciones. Reg. Rev. Interdiscip. En Estud. Reg. 1998, 62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Comité de Seguridad Alimentaria Mundial (CSA). Principios para la Inversión Responsable en la Agricultura y los Sistemas Alimentarios; Comité de Seguridad Alimentaria Mundial: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- García Winder, M.; Riveros, H.; Pavez, I.; Rodríguez, D.; Lam, F.; Arias Segura, J.; Herrera, D.; Agricultura (IICA). Cadenas Agroalimentarias: Un Instrumento Para Fortalecer La Institucionalidad Del Sector Agrícola y Rural; COMUNIICA, 5; Instituto Interamericano de Cooperación para la Agricultura (IICA): San José, Costa Rica, 2009; ISBN 978-92-9248-146-9. [Google Scholar]

- Albisu, L.M. Las cadenas agroalimentarias como elementos fundamentales para la competitividad de los productos en los mercados. Rev. Mex. De Agronegocios 2011, 28, 451–452. [Google Scholar]

- Agencia Catalana de Seguridad Alimentaria La Cadena Alimentaria. Principios y los Requisitos Generales de la Legislación Alimentaria. Reglamento (CE) No 178/2002. Available online: http://acsa.gencat.cat/es/seguretat_alimentaria/ (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Ramírez-Juárez, J. Régimen Alimentario y Agricultura Familiar. Elementos Para La Soberanía Alimentaria. Remexca 2023, 14, e3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moctezuma-López, G.; Espinosa-García, J.A.; Cuevas-Reyes, V.; Jolalpa-Barrera, J.L.; Romero-Santillán, F.; Vélez-Izquierdo, A.; Bustos Contreras, D.E. Innovación tecnológica de la cadena agroalimentaria de maíz para mejorar su competitividad: Estudio de caso en el estado de Hidalgo. Rev. Mex. De Cienc. Agrícolas 2010, 1, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía, Estadística e Informática, INEGI. Mapa digital de México Para Escritorio Versión 6.3. Proyectos. Proyecto Básico de Información 2020. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/temas/mapadigital/#Descargas (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía, Estadística e Informática, INEGI. Compendio de Información Geográfica Municipal 2010, Huejotzingo, Puebla; INEGI: Aguascalientes, México, 2010.

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía, Estadística e Informática, INEGI. Compendio de Información Geográfica Municipal 2010, Chiautzingo, Puebla; INEGI: Aguascalientes, México, 2010.

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía, Estadística e Informática, INEGI. Compendio de Información Geográfica Municipal 2010, Tlaltenango, Puebla; INEGI: Aguascalientes, México, 2010.

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía, Estadística e Informática, INEGI. Compendio de Información Geográfica Municipal 2010, San Salvador el Verde, Puebla; INEGI: Aguascalientes, México, 2010.

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía, Estadística e Informática, INEGI. Compendio de Información Geográfica Municipal 2010, Juan C. Bonilla, Puebla; INEGI: Aguascalientes, México, 2010.

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía, Estadística e Informática, INEGI. Compendio de Información Geográfica Municipal 2010, Calpan, Puebla; INEGI: Aguascalientes, México, 2010.

- ADICAP. Atlas de Riesgos Del Municipio de San Martín Texmelucan; ADICAP & Gobierno Municipal de San Martín Texmelucan: San Martín Texmelucan, México, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaría de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural del Gobierno de México Sistema de Información Agroalimentaria de Consulta, Siacon. Available online: http://www.gob.mx/siap/documentos/siacon-ng-161430 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía, Estadística e Informática, INEGI. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/#datos_abiertos (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Consejo Nacional de Población del Gobierno de México, CONAPO. Índice de Marginación (Carencias Poblacionales) Por Localidad, Municipio y Entidad. Available online: https://datos.gob.mx/busca/dataset/indice-de-marginacion-carencias-poblacionales-por-localidad-municipio-y-entidad (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social, CONEVAL. Medición de La Pobreza Por Grupos Poblacionales a Escala Municipal 2010, 2015 y 2020. Available online: https://www.coneval.org.mx/Medicion/Paginas/Pobreza_grupos_poblacionales_municipal_2010_2020.aspx (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Méndez Espinoza, J.A.; Valencia Bastida, I.; Ramírez Juárez, J.; Pérez Ramírez, N.; Regalado López, J.; Hernández Flores, J.A. Caracterización y Tipificación de Las Unidades Domésticas Que Participan En La Cadena Agroalimentaria Maíz-Tlacoyo. Agric. Soc. y Desarro. 2024, 21, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimone-Celorio, J.A.; Regalado-López, J.; Gallego-Moreno, F.J.; Pérez-Ramírez, N.; Méndez-Espinoza, J.A. Comparative Analysis of Four Corn (Zea Mays L.) Varieties, Transformed from Grain Corn into Tortilla. Agro Prod. 2024, 17, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regalado-López, J.; Castellanos-Alanis, A.; Pérez-Ramírez, N.; Méndez-Espinoza, J.A.; Hernández-Romero, E. Modelo Asociativo y de Organización Para Transferir La Tecnología Milpa Intercalada En Árboles Frutales (MIAF). Estud. Soc. 2020, 30, 2–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coller, X. Estudio de Casos, Madrid, Cuadernos Metodológicos; Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas: Madrid, España, 2005; Volume 30, ISBN 978-84-7476-387-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ponce Andrade, A.L. El Estudio de Caso Múltiple. Una estrategia de Investigación en el ámbito de la Administración. Rev. Publicando 2018, 5, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bulman, A.; Cordes, K.Y.; Mehranvar, L.; Merrill, E.; Fiedler, Y. Guía Sobre Incentivos Para la Inversión Responsable en la Agricultura y Los Sistemas Alimentarios. Roma, FAO y Centro Columbia sobre Inversión Sostenible, 1st ed.; FAO: Roma, Italia, 2021; ISBN 978-92-5-134575-7. [Google Scholar]

- Regalado López, J.; Mendoza, R.; Ríos Carmenado, I.; Díaz Puente, J.M. Adaptación del modelo leader en el territorio huejotzingo, puebla: Una nueva propuesta de desarrollo rural local. In Proceedings of the Actas del XV Congreso Internacional de Ingeniería de Proyectos, Huesca, España, 6–8 July 2011; E.T.S.I. Agrónomos (UPM): Madrid, España, 2011; pp. 1533–1545. [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla Montero, A.; De los Ríos Carmenado, I.; Yagüe, B. Trabajando con la gente en los proyectos de desarrollo rural: Una conceptualización desde el Aprendizaje Social. In Modelos Para el Desarrollo Rural Con Enfoque Territorial en México; Altres Costa-Amic Editores, S.A. de C.V.: Puebla, México, 2011; ISBN 978-968-839-585-1. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía, Estadística e Informática, INEGI. Panorama Sociodemográfico de Puebla. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020, 1st ed.; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía de México: Aguascalientes, México, 2021; Volume 1, ISBN 304.601072.

- Turrent Fernández, A.; Cortés Flores, J.I.; Espinosa Calderón, A.; Hernández Romero, E.; Camas Gómez, R.; Torres Zambrano, J.P.; Zambada Martínez, A. MasAgro o MIAF ¿Cuál Es La Opción Para Modernizar Sustentablemente La Agricultura Tradicional de México. Remexca 2017, 8, 1169–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Centro Internacional de maíz y Trigo; CIMMYT; Ministry of Agriculture, Government of Mexico; Government of the State of Puebla. The Puebla Project: Seven Years of Experience, 1967–1973, 1st ed.; CIMMYT: Puebla, México, 1974; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Madrigal-Rodríguez, J.; Villanueva-Verduzco, C.; Sahagún-Castellanos, J.; Acosta Ramos, M.; Martínez Martínez, L.; Espinosa Solares, T. Ensayos de producción de huitlacoche (Ustilago maydis Cda.) hidropónico en invernadero. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Hortic. 2010, 16, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés Flores, J.I.; Turrent Fernández, A. La Milpa Intercalada en Árboles Frutales (MIAF) Tecnología Multiobjetivo Para el Desarrollo de la Agricultura en Laderas; Colegio de Postgraduados: Texcoco de Mora, México, 2021; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ordoñez-Ovalle, J.; Gómez-Martínez, E.; Soto-Pinto, L.; González-Santiago, M.V. El sistema milpa intercalado con árboles frutales (MIAF): Evaluación agroecológica a diez años de su implementación en Chamula, Chiapas, México. Rev. Campo-Territ. 2022, 17, 109–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Hernández, L.M.; Almeraya-Quintero, S.X.; Guajardo-Hernández, L. La producción de tlacoyos como alternativa de desarrollo en San Miguel Tianguizolco, Puebla, México. Agro Product. 2017, 10, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Cárdenas, T.; Thomé-Ortiz, H.; Ávalos De La Cruz, D.A.; Escalona-Maurice, M.; Gómez-Merino, F.C. El Tlacoyo Como Recurso Alimentario, y Su Relación Con La Oferta Turística Local: Casos Texcoco y Chiconcuac, Estado de México En México. Agro Prod. 2020, 13, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Economía del Gobierno de México Tlaltenango: Economía, Empleo, Equidad, Calidad de Vida, Educación, Salud y Seguridad Pública. Available online: https://www.economia.gob.mx/datamexico/es/profile/geo/tlaltenango (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Cabral Martell, A. Las figuras asociativas como alternativa en los Agronegocios. Rev. Mex. De Agronegocios 2004, VIII, 378–389. [Google Scholar]

- Apolo 30 Tipo 8–Tortilladoras Apolo. Tortilladoras Apolo. 2021. Available online: https://tortilladorasapolo.com/apolo-30-basica/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- CFS-FAO-UN. (2024). PROGRAMA INTERNACIONAL SOBRE LOS PRINCIPIOS DE INVERSION RESPONSABLE EN LA AGRICULTURA Y LOS SISTEMAS ALIMENTARIOS, PRINCIPIOS CSA-IRA. Available online: https://www.colpos.mx/cp_pdf/eventos/2024/guia_curso_principios_ira.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Secretaría de Economía del Gobierno de México Calpan: Economía, Empleo, Equidad, Calidad de Vida, Educación, Salud y Seguridad Pública. Available online: https://www.economia.gob.mx/datamexico/es/profile/geo/calpan (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Littaye, A. The Role of the Ark of Taste in Promoting Pinole, a Mexican Heritage Food. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 42, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaleta, M.; Gebremedhin, B.; Hoekstra, D. Smallholder Commercialization: Processes, Determinants and Impact. In Discussion Paper No. 18. Improving Productivity and Market Success (IPMS) of Ethiopian Farmers Project; International Livestock Research Institute: Nairobi, Kenya, 2009; 55p. [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla Adolfo, A.; De Los Ríos Carmenado, I. Jornadas de Diálogo Para la inclusión de los Principios Para la Inversión Responsable en la Agricultura (IAR) y las Directrices Voluntarias de Gobernanza de la Tierra (DVGT) en el Ecosistema Universitario de Latinoamérica; Conclusiones; Grupo GESPLAN, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid: Madrid, España, 2018; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- GESPLAN, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. Programa Internacional sobre los Principios de Inversión Responsable en la Agricultura y los Sistemas Alimentarios FAO; Valoración de Objetivos de los Principios CSA-IRA en la Tercera Edición del Programa; Universidad Politécnica de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Aliaga, R.; De Los Rios Carmenado, I.; Cazorla Montero, A.; Huamán, C.; Amparo, E. Definición de objetivos prioritarios para la implementación de los Principios CSA-IRA en la sierra central de Perú. In Proceedings of the 27th International Congress on Project Management and Engineering, Donostia-San Sebastián, Spain, 10–13 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Aliaga, R.; De Los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; San Martín Howard, F.; Calle Espinoza, S.; Huamán Cristóbal, A. Integration of the Principles of Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems CFS-RAI from the Local Action Groups: Towards a Model of Sustainable Rural Development in Jauja, Peru. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Aliaga, R.; De Los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; Huamán Cristóbal, A.E.; Aliaga Balbín, H.; Marroquín Heros, A.M. Competencies and Capabilities for the Management of Sustainable Rural Development Projects in the Value Chain: Perception from Small and Medium-Sized Business Agents in Jauja, Peru. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Inversión Responsable en la Agricultura y los Sistemas Alimentarios—Dirigido al Sector Privado. Academia de Aprendizaje Electrónico de la FAO. 2022. Available online: https://elearning.fao.org/course/view.php?id=706 (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Friedmann, J. Planning as Social Learning. Work. Pap. 1981, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Winch, G. Rethinking Project Management: Project Organizations as Information Processing Systems? In Proceedings of the PMI Research Conference, London, UK, 11–14 July 2004; Project Management Institute: Newtown Square, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Midgley, J. Social Development: Theory and Practice; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4129-4778-7. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta Mereles, M.L.; De los Ríos Carmenado, I.; Ávila Cerón, C.A.; Castañeda Sepulveda, R. Inversión responsable en procesos de sustitución de cultivos ilícitos desde el modelo “Trabajando con Personas”: Estudio de caso Guaviare (Colombia). In Proceedings of the Comunicaciones presentadas al XXVII Congreso Internacional de Dirección e Ingeniería de Proyectos, Donostia-San Sebastián, Spain, 10–13 June 2023; AEIPRO, Asociación Española de Dirección e Ingeniería de Proyectos: Donostia-San Sebastián, Spain, 2023; Volume 197. [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla Montero, A.; De Los Ríos Carmenado, I. Rural Development as “Working With People”: A Proposal for Policy Management in Public Domain, 1st ed.; E.T.S.I. Agrónomos (UPM): Madrid, España, 2012; ISBN 978-84-615-7154-3. [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla-Montero, A.; De Los Ríos-Carmenado, I. From “Putting the Last First” to “Working with People” in Rural Development Planning: A Bibliometric Analysis of 50 Years of Research. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Ríos Carmenado, I.; Rivera, M.; García, C. Redefining Rural Prosperity through Social Learning in the Cooperative Sector: 25 Years of Experience from Organic Agriculture in Spain. Land Use Policy 2016, 54, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mur Nuño, C.; De los Ríos Carmenado, I. Hacia una “Gobernanza basada proyectos” desde los ODS y los criterios ASG: El caso de los Bancos de Alimentos. In Proceedings of the 28th International Congress on Project Management and Engineering, Jaén, España, 3–4 July 2024; pp. 1775–1793. [Google Scholar]

- Requelme, N.; Afonso, A. The Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture (CFS-RAI) and SDG 2 and SDG 12 in Agricultural Policies: Case Study of Ecuador. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, A.; Velasquez-Fernandez, A.; Rodriguez-Vasquez, M.I.; Cuervo-Guerrero, G. Territorial Analysis Through the Integration of CFS-RAI Principles and the Working with People Model: An Application in the Andean Highlands of Peru. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachipuendo, C.; Requelme, N.; Sandoval, C.; Afonso, A. Sustainable Rural Development Based on CFS-RAI Principles in the Production of Healthy Food: The Case of the Kayambi People (Ecuador). Sustainability 2025, 17, 2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.; Gibbon, D.P.; Gulliver, A.; Hall, M. Sistemas de Producción Agropecuaria y Pobreza: Como Mejorar Los Medios de Subsistencia de Los Pequeños Agricultores En Un Mundo Cambiante; FAO: Rome, Italy; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-92-5-104627-2. [Google Scholar]

| Elements | National, México | State, Puebla |

|---|---|---|

| Total production units | 4,440,265 | 440,752 |

| Surface area for agricultural use (ha) | 26,104,422.68 | 1,015,173.77 |

| Sown area (ha) | 20,547,097.17 | 926,890.58 |

| Receiving “senior adults” support | 895,837 | 85,728 |

| Tractor use | 1,793,338 | 187,816 |

| Credit use | 265,508 | 14,437 |

| Insurance use | 78,140 | 621 |

| Agricultural Species | Planted Surface (ha) | Production | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volume (tons) | Value (Thousands of Mexican Pesos) | ||

| Corn | 21,178.7 | 38,579.1 | 269,672.8 |

| Beans | 1791.2 | 1767.9 | 26,323.3 |

| Peach | 543.1 | 3775.1 | 31,607.4 |

| Apple tree | 191.8 | 1203.5 | 9525.9 |

| Pear tree | 796.4 | 6646.2 | 22,895.3 |

| Hickory | 127.0 | 534.7 | 15,673.1 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Territory | Municipality | Huejotzingo | Tlaltenango | Calpan |

| Locality | Miguel Tianguizolco | No location | San Andrés | |

| Production | Product | Corn, beans, ayocote and pumpkin. | Corn | Fruits, poblano peppers and corn |

| Farmers | 50 | 500 | 250 | |

| Total Surface | 100 ha | 1200 ha | 208 ha | |

| Transformation | Product | Tlacoyo and tortilla | Tortilla and tostada | Chile en Nogada |

| Families | 600 | 100 | 80 | |

| Commercialization | Points of sale | 50 markets in CDMX y Edo. de México | 280 places, e.g., miscellaneous, schools, and others. | 150 restaurants and 5 events. |

| A. Maíz-Frijol Guía | B. SPR Campo Lima | C. Guardianes Calpan | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Huejotzingo | Tlaltenango | Calpan |

| Irrigation | Rainfed and well | Well and rainfed | Rainfed and well |

| Surface area | 6 ha | 45 ha | 8 ha |

| Members | 5 | 7 | 17 |

| Average age | 49 years | 46 years | 55 years |

| Schooling | 6 years | 8 years | 9 years |

| Production | MIAF * | seed, grain and corn | Fruits, chile poblano |

| Transformation | Tlacoyos and gorditas | tortilla de nixtamal | Chiles en nogada, others |

| Marketing | Local markets | tortillería shop, stores | Restaurants, fairs |

| Production cycles | 2 to 6 months | 2 to 6 months | 3 to 4 months |

| Contract labor | 86 | 90 | 40 |

| cost–benefit analysis | 3.5 | 3.4 | 4 |

| Associative figure | Family Unit | Rural Production Society | Cooperative |

| CFS-RIA Principle | Progress Indicators * | AM α | SL β | GC θ | Identified Strengths | Identified Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Contribute to food security and nutrition |

| 84 | 90 | 80 | There has been an increase in the production of corn and other staple foods, as well as an increase in crop diversification, local consumption, and self-consumption of nutritious foods. | Dependence on external inputs (fertilizers and seeds) for corn. Limited access to fair markets. |

| 80 | 74 | 88 | |||

| 88 | 88 | 94 | |||

| 86 | 96 | 94 | |||

| 94 | 94 | 94 | |||

| GLP ** | 86 | 88 | 90 | |||

| 2. Contribute to sustainable and inclusive economic development and the eradication of poverty |

| 90 | 90 | 96 | Family income is strengthened through crop diversification and the sale of surpluses and by-products. The action groups optimize the use of resources and improve profitability in corn and polycrop production. Increased adaptation of technologies and practices to local needs. | Prioritization of economic profitability over sustainability. Lack of access to credit or savings banks. Difficulty competing with large producers and companies or switching to a high value-added market through product transformation. |

| 84 | 86 | 96 | |||

| 80 | 88 | 94 | |||

| 82 | 80 | 90 | |||

| GLP ** | 84 | 86 | 94 | |||

| 9. Incorporate inclusive and transparent governance structures, processes, and grievance mechanisms |

| 80 | 84 | 90 | The association of small producers is the main objective of the interventions, encouraging their participation in decision-making and their association in cooperatives or societies. The relationship with academic institutions is strengthened through research projects and field training. | Limitations of governmental structures. Lack of formalization due to the absence of specific laws. |

| 78 | 92 | 94 | |||

| 82 | 88 | 96 | |||

| 84 | 86 | 94 | |||

| GLP ** | 82 | 88 | 94 |

| WWP Model | Application Indicator * | AM α | SL β | GC θ | Identified Strengths | Identified Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Technical–Entrepreneurial Component |

| 74 | 82 | 98 | The application of this component is high, especially in the Campo Lima and Guardianes de Saberes Sabores de Calpan groups, because they have a high level of associativity within their groups. | Consolidate the entrepreneurial component of the “Campo Lima” group. Replicate the experience of the Guardianes de Saberes y Sabores de Calpan cooperative in the other two agri-food cases. Generate commercial synergies among the three groups. |

| 80 | 88 | 92 | |||

| 90 | 90 | 90 | |||

| 80 | 92 | 94 | |||

| 88 | 96 | 94 | |||

| GLP ** | 82 | 90 | 94 | |||

| 2. Ethical–Social Component |

| 80 | 84 | 90 | The participation of rural groups in decision-making is promoted and gender equity is fostered, although inequalities persist. | Inequality in access to resources and opportunities. Persistence of traditional gender roles. Difficulty in achieving a balance in the participation of all stakeholders. Lack of trust in institutions and agents for dialog. Abuse of intermediaries that affect fair trade. |

| 82 | 90 | 92 | |||

| 80 | 80 | 96 | |||

| 82 | 84 | 86 | |||

| 88 | 90 | 94 | |||

| GLP ** | 82 | 86 | 92 | |||

| 4. Social Learning process-approach |

| 78 | 82 | 88 | Collective learning and the adaptation of strategies based on experience are encouraged, as well as an interdisciplinary reflection and analysis of the actions undertaken. | Difficulty in systematizing information and learning. Need to strengthen monitoring and evaluation capacities. Resistance to evaluation and feedback. |

| 92 | 90 | 90 | |||

| 88 | 88 | 90 | |||

| 84 | 92 | 90 | |||

| GLP ** | 86 | 88 | 90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Regalado-López, J.; Maimone-Celorio, J.A.; Pérez-Ramírez, N. Strengthening of the Rural Community and Corn Food Chain Through the Application of the WWP Model and the Integration of CFS-RAI Principles in Puebla, México. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5442. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125442

Regalado-López J, Maimone-Celorio JA, Pérez-Ramírez N. Strengthening of the Rural Community and Corn Food Chain Through the Application of the WWP Model and the Integration of CFS-RAI Principles in Puebla, México. Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5442. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125442

Chicago/Turabian StyleRegalado-López, José, José Antonio Maimone-Celorio, and Nicolás Pérez-Ramírez. 2025. "Strengthening of the Rural Community and Corn Food Chain Through the Application of the WWP Model and the Integration of CFS-RAI Principles in Puebla, México" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5442. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125442

APA StyleRegalado-López, J., Maimone-Celorio, J. A., & Pérez-Ramírez, N. (2025). Strengthening of the Rural Community and Corn Food Chain Through the Application of the WWP Model and the Integration of CFS-RAI Principles in Puebla, México. Sustainability, 17(12), 5442. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125442