Nature Exposure and Subjective Well-Being: The Mediating Roles of Connectedness to Nature and Awe

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Nature Exposure and Well-Being

1.2. Connectedness to Nature and Well-Being

1.3. Awe and Well-Being

1.4. Awe as a Mediator of the Influence of CN on Subjective Well-Being

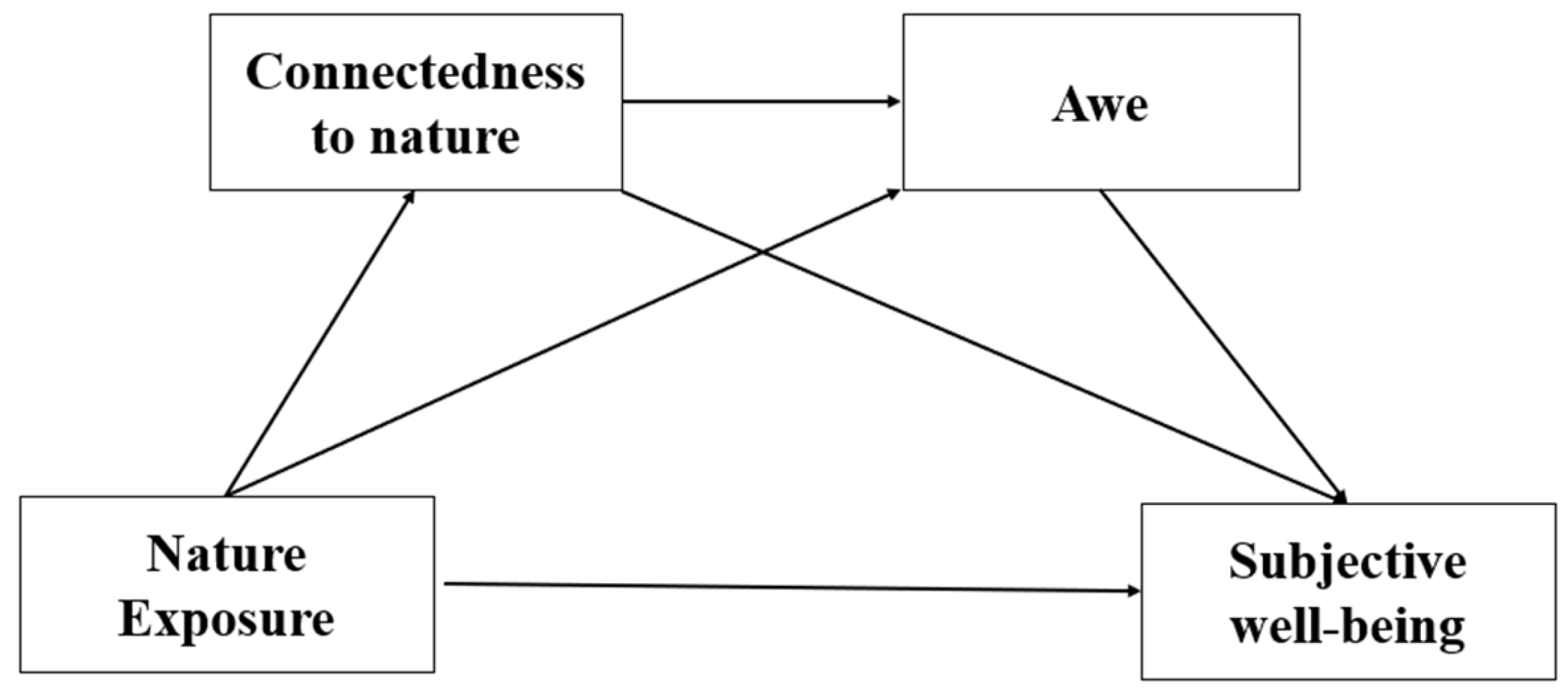

1.5. Current Research

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Nature Exposure

2.2.2. Connectedness to Nature

2.2.3. Inclusion of Nature in Self

2.2.4. Awe

2.2.5. Subjective Well-Being

2.2.6. Nature Knowledge

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Bias Test

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

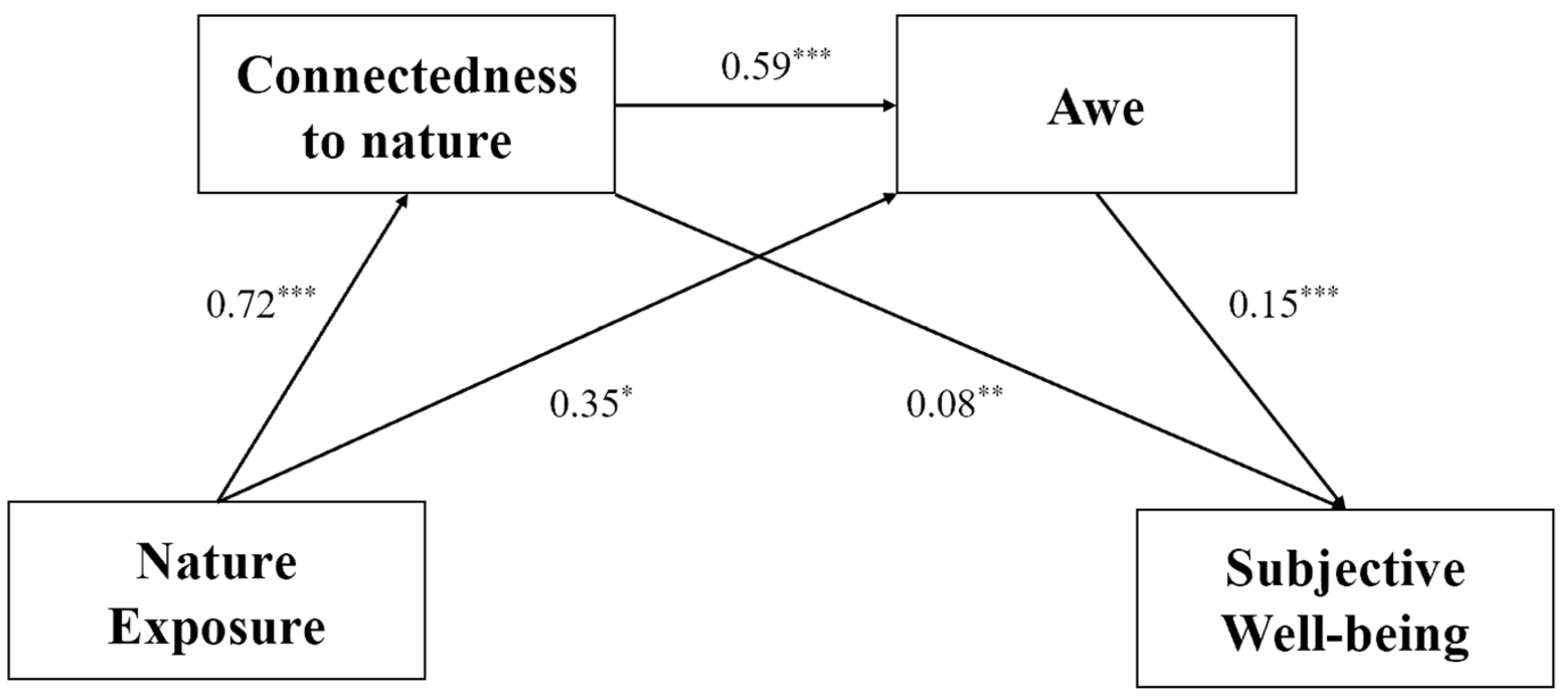

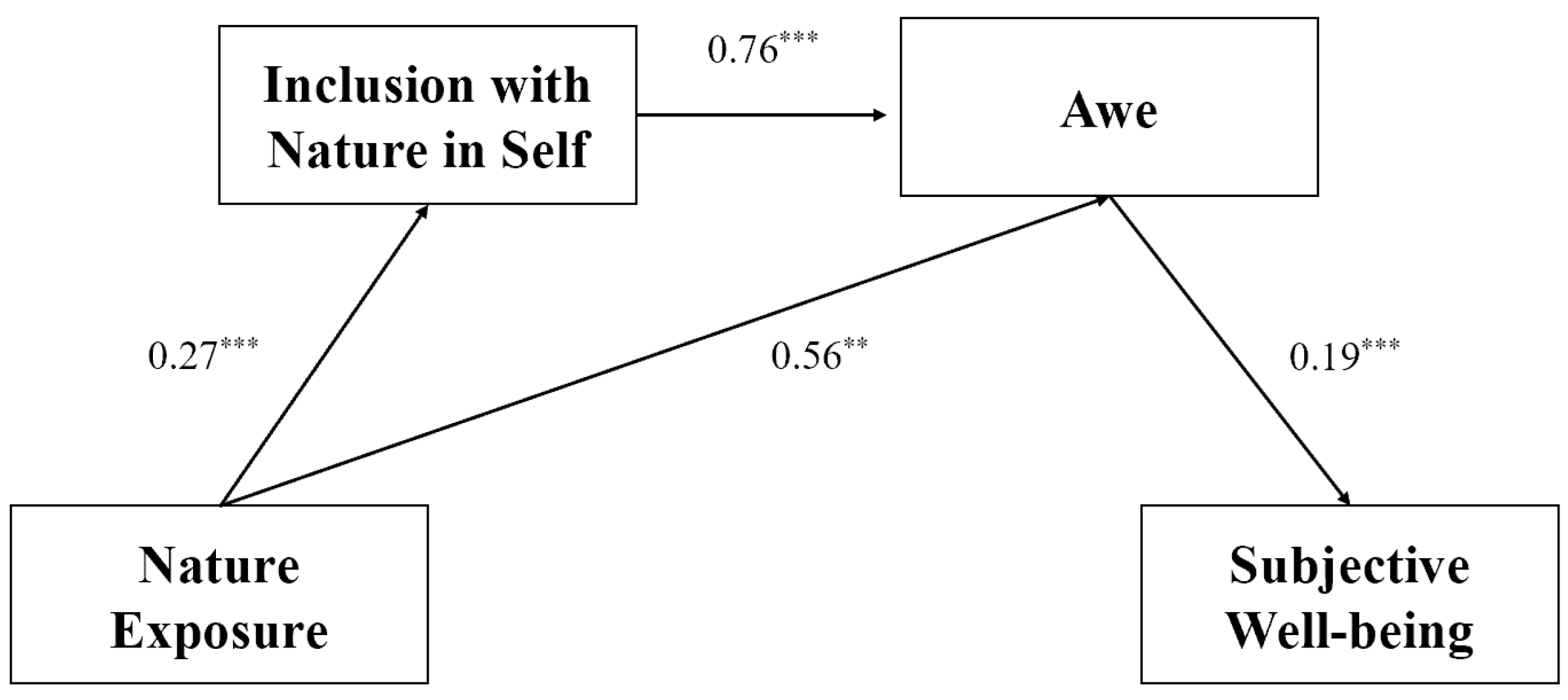

3.3. Mediating Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M.; Bruehlman-Senecal, E.; Dolliver, K. Why Is Nature Beneficial?: The Role of Connectedness to Nature. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 607–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward an Integrative Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, C.A.; Passmore, H.-A.; Ishii, R.; Chistopolskaya, K.A.; Vowinckel, J.; Nikolaev, E.L.; Semikin, G.I. Engaging with Natural Beauty May Be Related to Well-Being Because It Connects People to Nature: Evidence from Three Cultures. Ecopsychology 2017, 9, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.; Borodulin, K.; Neuvonen, M.; Paronen, O.; Tyrväinen, L. Analyzing the Mediators between Nature-Based Outdoor Recreation and Emotional Well-Being. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 37, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Hamlin, I.; Butler, C.W.; Thomas, R.; Hunt, A. Actively Noticing Nature (Not Just Time in Nature) Helps Promote Nature Connectedness. Ecopsychology 2022, 14, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, C.; Passmore, H.-A.; Nisbet, E.; Zelenski, J.; Dopko, R. Flourishing in Nature: A Review of the Benefits of Connecting with Nature and Its Application as a Wellbeing Intervention. Int. J. Wellbeing 2015, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballew, M.T.; Omoto, A.M. Absorption: How Nature Experiences Promote Awe and Other Positive Emotions. Ecopsychology 2018, 10, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berto, R. The Role of Nature in Coping with Psycho-Physiological Stress: A Literature Review on Restorativeness. Behav. Sci. 2014, 4, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Berg, A.E.; Hartig, T.; Staats, H. Preference for Nature in Urbanized Societies: Stress, Restoration, and the Pursuit of Sustainability. J. Soc. Issues 2007, 63, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Weinstein, N.; Bernstein, J.; Brown, K.W.; Mistretta, L.; Gagné, M. Vitalizing Effects of Being Outdoors and in Nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, G.N.; Hamilton, J.P.; Daily, G.C. The Impacts of Nature Experience on Human Cognitive Function and Mental Health. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1249, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanahan, D.F.; Fuller, R.A.; Bush, R.; Lin, B.B.; Gaston, K.J. The Health Benefits of Urban Nature: How Much Do We Need? BioScience 2015, 65, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P. Natural Environments and Subjective Wellbeing_ Different Types of Exposure Are Associated with Different Aspects of Wellbeing. Health Place 2017, 45, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, E.A.; Estes, D. The Effect of Contact with Natural Environments on Positive and Negative Affect: A Meta-Analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 10, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective Well-Being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markevych, I.; Schoierer, J.; Hartig, T.; Chudnovsky, A.; Hystad, P.; Dzhambov, A.M.; De Vries, S.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Brauer, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Exploring Pathways Linking Greenspace to Health: Theoretical and Methodological Guidance. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigsby-Toussaint, D.S.; Turi, K.N.; Krupa, M.; Williams, N.J.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R.; Jean-Louis, G. Sleep Insufficiency and the Natural Environment: Results from the US Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey. Prev. Med. 2015, 78, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Kawada, T. Effect of Forest Environments on Human Natural Killer (NK) Activity. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2011, 24, 39S–44S. [Google Scholar]

- White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Grellier, J.; Wheeler, B.W.; Hartig, T.; Warber, S.L.; Bone, A.; Depledge, M.H.; Fleming, L.E. Spending at Least 120 Minutes a Week in Nature Is Associated with Good Health and Wellbeing. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress Recovery during Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R.; Wilson, E.O. The Biophilia Hypothesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, A.; Richardson, M.; Sheffield, D.; McEwan, K. The Relationship Between Nature Connectedness and Eudaimonic Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. J. Happiness Stud. 2020, 21, 1145–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; White, M.P.; Hunt, A.; Richardson, M.; Pahl, S.; Burt, J. Nature Contact, Nature Connectedness and Associations with Health, Wellbeing and pro-Environmental Behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 68, 101389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keltner, D.; Haidt, J. Approaching Awe, a Moral, Spiritual, and Aesthetic Emotion. Cogn. Emot. 2003, 17, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Huo, Y.; Wang, J.; Bai, Y.; Zhao, M.; Di, M. Awe of Nature and Well-Being: Roles of Nature Connectedness and Powerlessness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2023, 201, 111946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiota, M.N.; Keltner, D.; Mossman, A. The Nature of Awe: Elicitors, Appraisals, and Effects on Self-Concept. Cogn. Emot. 2007, 21, 944–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiota, M.N.; Keltner, D.; John, O.P. Positive Emotion Dispositions Differentially Associated with Big Five Personality and Attachment Style. J. Posit. Psychol. 2006, 1, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piff, P.K.; Feinberg, M.; Dietze, P.; Stancato, D.M.; Keltner, D. Awe, the Small Self, and Prosocial Behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 108, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.; Yang, S.; Laurent, S.M. No One Is an Island: Awe Encourages Global Citizenship Identification. Emotion 2023, 23, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, M.; Vohs, K.D.; Aaker, J. Awe Expands People’s Perception of Time, Alters Decision Making, and Enhances Well-Being. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 1130–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.L.; Monroy, M.; Keltner, D. Awe in Nature Heals: Evidence from Military Veterans, at-Risk Youth, and College Students. Emotion 2018, 18, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monroy, M.; Uğurlu, Ö.; Zerwas, F.; Corona, R.; Keltner, D.; Eagle, J.; Amster, M. The Influences of Daily Experiences of Awe on Stress, Somatic Health, and Well-Being: A Longitudinal Study during COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aron, A.; Aron, E.N.; Smollan, D. Inclusion of Other in the Self Scale and the Structure of Interpersonal Closeness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 63, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, A.J.; Dopko, R.L.; Passmore, H.-A.; Buro, K. Nature Connectedness: Associations with Well-Being and Mindfulness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 51, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamitsis, I.; Francis, A.J.P. Spirituality Mediates the Relationship between Engagement with Nature and Psychological Wellbeing. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, E.A. Towards Ecological Self: Deep Ecology Meets Constructionist Self-Theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 1996, 16, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.; Seligman, M.E.P. Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-19-516701-6. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-7432-2297-6. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Hu, J.; Jing, F.; Nguyen, B. From Awe to Ecological Behavior: The Mediating Role of Connectedness to Nature. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.T.; Leung, A.K.-Y.; Chan, S.H.M. Through the Lens of a Naturalist: How Learning about Nature Promotes Nature Connectedness via Awe. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 92, 102069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samus, A.; Freeman, C.; Van Heezik, Y.; Krumme, K.; Dickinson, K.J. How Do Urban Green Spaces Increase Well-Being? The Role of Perceived Wildness and Nature Connectedness. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 82, 101850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsko, C.; Lindberg, K. Experiencing Connection with Nature: The Matrix of Psychological Well-Being, Mindfulness, and Outdoor Recreation. Ecopsychology 2013, 5, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, S.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Natural Environments—Healthy Environments? An Exploratory Analysis of the Relationship between Greenspace and Health. Environ. Plan. Econ. Space 2003, 35, 1717–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M. The Connectedness to Nature Scale: A Measure of Individuals’ Feeling in Community with Nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, L.; Jianping, W.; Psychology, D.O. Revise of the Connectedness to Nature Scale and Its Reliability and Validity. China J. Health Psychol. 2016, 24, 1347–1350. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, P.W. Inclusion with Nature: The Psychology of Human-Nature Relations. In Psychology of Sustainable Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, A. Subjective Measures of Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 1976, 31, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siman, L.; Keting, L.; Tiantian, L.; Li, L. The Impact of Mindfulness on Subjective Well-Being of College Students: The Mediating Effects of Emotion Regulation and Resilience. J. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 38, 889. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS Procedures for Estimating Indirect Effects in Simple Mediation Models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joye, Y.; Bolderdijk, J.W. An Exploratory Study into the Effects of Extraordinary Nature on Emotions, Mood, and Prosociality. Front. Psychol. 2015, 5, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T. Social Beings: Core Motives in Social Psychology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; ISBN 1-119-49273-4. [Google Scholar]

- Leopold, A. A Sand County Almanac: With Essays on Conservation from Round River; Ballantine Books: New York, NY, USA, 1986; ISBN 0-345-34505-3. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Ryan, K. Subjective Well-Being: A General Overview. South Afr. J. Psychol. 2009, 39, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszak, T.E.; Gomes, M.E.; Kanner, A.D. Ecopsychology: Restoring the Earth, Healing the Mind.; Sierra Club Books: Oakland, CA, USA, 1995; ISBN 0-87156-499-8. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnentag, S.; Binnewies, C.; Mojza, E.J. Staying Well and Engaged When Demands Are High: The Role of Psychological Detachment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bloom, J.; Kinnunen, U.; Korpela, K. Exposure to Nature versus Relaxation during Lunch Breaks and Recovery from Work: Development and Design of an Intervention Study to Improve Workers’ Health, Well-Being, Work Performance and Creativity. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frantz, C.M.; Mayer, F.S. The Importance of Connection to Nature in Assessing Environmental Education Programs. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2014, 41, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossack, A.; Bogner, F.X. How Does a One-Day Environmental Education Programme Support Individual Connectedness with Nature? J. Biol. Educ. 2012, 46, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liefländer, A.K.; Fröhlich, G.; Bogner, F.X.; Schultz, P.W. Promoting Connectedness with Nature through Environmental Education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2013, 19, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, C.D.; Profice, C.C.; Collado, S. Nature Experiences and Adults’ Self-Reported Pro-Environmental Behaviors: The Role of Connectedness to Nature and Childhood Nature Experiences. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Kuczkowski, R. The Imaginary Audience, Self-Consciousness, and Public Individuation in Adolescence. J. Pers. 1994, 62, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studente, S.; Seppala, N.; Sadowska, N. Facilitating Creative Thinking in the Classroom: Investigating the Effects of Plants and the Colour Green on Visual and Verbal Creativity. Think. Ski. Creat. 2016, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plambech, T.; Konijnendijk Van Den Bosch, C.C. The Impact of Nature on Creativity—A Study among Danish Creative Professionals. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Murphy, S.A. Happiness Is in Our Nature: Exploring Nature Relatedness as a Contributor to Subjective Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 2011, 12, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.; Othman, N.; Hamzah, H.; Zainal, M.H.; Malek, N.A. A Systematic Review of Botanical Gardens Towards Eco Restoration and Connectedness to Nature for Psychological Restoration. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1067, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.INS | 4.31 | 1.72 | ||||

| 2. CN | 3.63 | 0.45 | 0.39 ** | |||

| 3. Awe | 4.79 | 1.02 | 0.32 ** | 0.66 ** | ||

| 4. SWB | 10.83 | 2.38 | 0.26 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.52 ** | |

| 5. NE | 2.24 | 0.65 | 0.34 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.19 ** |

| Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | Relative Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 0.17 | 0.041 | 0.101 | 0.260 | |

| Ind NE–CN–SWB | 0.06 | 0.025 | 0.015 | 0.115 | 34% |

| Ind NE–Awe–SWB | 0.05 | 0.024 | 0.011 | 0.108 | 30% |

| Ind NE–CN–Awe–SWB | 0.06 | 0.020 | 0.029 | 0.108 | 36% |

| Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | Relative Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 0.19 | 0.046 | 0.107 | 0.287 | |

| Ind NE–CN–SWB | 0.04 | 0.025 | −0.002 | 0.096 | |

| Ind NE–Awe–SWB | 0.11 | 0.036 | 0.043 | 0.184 | 58% |

| Ind NE–CN–Awe–SWB | 0.04 | 0.015 | 0.014 | 0.073 | 21% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, M.; Luo, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, R.; Liu, X. Nature Exposure and Subjective Well-Being: The Mediating Roles of Connectedness to Nature and Awe. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5406. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125406

Zhou M, Luo Y, Xu Z, Zhang R, Liu X. Nature Exposure and Subjective Well-Being: The Mediating Roles of Connectedness to Nature and Awe. Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5406. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125406

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Meihui, Ying Luo, Zihan Xu, Ronghua Zhang, and Xiaoliang Liu. 2025. "Nature Exposure and Subjective Well-Being: The Mediating Roles of Connectedness to Nature and Awe" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5406. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125406

APA StyleZhou, M., Luo, Y., Xu, Z., Zhang, R., & Liu, X. (2025). Nature Exposure and Subjective Well-Being: The Mediating Roles of Connectedness to Nature and Awe. Sustainability, 17(12), 5406. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125406