Abstract

Climate change is projected to increase the intensity and frequency of natural hazards such as heat waves, extreme rainfall, heavy snowfall, typhoons, droughts, floods, and cold waves, potentially impacting the operational safety of critical infrastructure, including nuclear power plants (NPPs). Although quantitative indicators exist to screen-out natural hazards at NPPs, comprehensive methodologies for assessing climate-related hazards remain underdeveloped. Furthermore, given the variability and uncertainty of climate change, it is realistically and resource-wise difficult to evaluate all potential risks quantitatively. Using a structured expert elicitation approach, this study systematically identifies and prioritizes climate-related natural hazards for Korean NPPs. An iterative Delphi survey involving 42 experts with extensive experience in nuclear safety and systems was conducted and also evaluated using the best–worst scaling (BWS) method for cross-validation to enhance the robustness of the Delphi priorities. Both methodologies identified extreme rainfall, typhoons, marine organisms, forest fires, and lightning as the top five hazards. The findings provide critical insights for climate resilience planning, inform vulnerability assessments, and support regulatory policy development to mitigate climate-induced risks to Korean nuclear power plants.

1. Introduction

Climate change has increased the frequency of natural hazards such as heat waves, extreme rains, heavy snowfall, typhoons, droughts, floods, and cold waves [1,2,3,4]. Globally, the number of climate change-related events resulting in human and economic losses continues to rise [5,6]. For example, Europe experienced unseasonably high temperatures from late 2022 to early January 2023, whereas Southeast Asia experienced a severe heat wave in April 2023 [1,7]. Furthermore, in April 2023, Chicago experienced a record-high temperature, followed four days later by a sudden drop to subzero temperatures, resulting in heavy snowfall [7]. In East Africa, below-average rainfall during the rainy season over the last few years has resulted in widespread and prolonged droughts. However, in 2023, extreme rains caused widespread flooding, displacing a large number of people [7,8].

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, climate change is expected to increase the intensity and frequency of natural disasters [9]. As a result, severe natural disasters can pose both direct and indirect threats to the safety and operation of critical infrastructure, such as nuclear power plants [10,11,12,13]. Nuclear power plants must be designed to operate reliably in the event of natural hazards [14,15]. However, changes in the frequency and intensity of natural hazards caused by climate change may affect the safety and operation of nuclear power plants [16,17,18,19,20]. For example, in Texas—a region typically known for its warm climate—a nuclear power plant was tripped due to a sudden cold snap that froze sensing lines [17,21]. Meanwhile, in France, heatwaves and abnormally high temperatures have frequently caused nuclear power plants to close or reduce production [11,22,23]. In Korea, changes in sea temperature have accelerated the appearance of marine organisms, necessitating the shutdown of several nuclear power plants [11]. Additionally, in several countries, nuclear power plants have been halted due to off-site power outages caused by typhoons and hurricanes [11]. Therefore, effective protective designs and countermeasures against natural hazards associated with climate change must be implemented to ensure the operation and safety of nuclear power plants [17,24].

Research on nuclear power plants in response to climate change is underway [11,20,25,26,27]. For example, Kopytko and Perkins analyzed the impact of sea-level rise, coastal erosion, storms, floods, and heatwaves on nuclear power plants [25]. Ahmad empirically confirmed that the frequency of nuclear power plant shutdowns has significantly increased due to climate change [26]. Meanwhile, Linnerud et al. pointed out that rising temperatures can decrease the thermal efficiency of nuclear power plants and increase the risk of operational shutdowns [27]. Furthermore, the guidelines of various nuclear power agencies specify that climate change should be considered to ensure the safety of nuclear power plants [16,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. These guidelines emphasize the assessment of the impacts of climate change on nuclear power plant operation and protection design. Although several guidelines and studies have addressed assessing external events, including climate-related events, quantitative assessments of hazards reflecting climate change are minimal. Probabilistic safety assessments (PSA) for natural hazards other than earthquakes are also minimal [11,35,36]. It is practically impossible to thoroughly assess all natural hazards associated with climate change due to their diversity and limited resources. Therefore, it is critical to prioritize natural hazards related to climate change that affect nuclear power plants to maximize resource utilization and respond effectively.

This study identified natural hazards associated with climate change for nuclear power plants in Korea, and priorities were established using the Delphi method. When prior research or standardized data is insufficient, the Delphi method is a qualitative evaluation approach that gathers expert intuition and opinions to reach consensus [37,38,39,40]. The Delphi method is characterized by respondent anonymity, iterative feedback surveys, and statistical processing of responses [41,42]. It effectively prevents distorted communication during committee or expert discussions and issues in which opinions may be skewed due to group pressure or conflict. However, the Delphi method has limitations. Because it relies heavily on experts’ subjective and intuitive judgment, it can lead to bias in experts’ opinions. This study assembled a panel of 42 nuclear experts to ensure a diverse range of perspectives. After each round of the Delphi survey, we calculated the coefficient of variation—a measure of the stability of expert opinions—to determine whether sufficient consensus had been reached and thus conclude the survey. Additionally, we employed the best–worst scaling (BWS) method to cross-validate the priority rankings derived from the Delphi process, thereby offsetting the uncertainty inherent in qualitative evaluations.

2. Research Method

This study used literature and historical data from Korean sources to identify external hazards, whereas climate change-related natural hazards affecting nuclear power plants were identified through expert elicitation. These climate change-related natural hazards were prioritized using two rounds of Delphi surveys. The Delphi surveys evaluated selected natural hazards using two criteria: frequency of occurrence (likelihood) and impact (severity of consequences). Both likelihood and impact were rated on a five-point Likert scale: 1 = very low; 2 = low; 3 = moderate; 4 = high; and 5 = very high. In the second round, experts were presented with summary statistics from the first round, including the mean, median, and interquartile range for each criterion, allowing them to reflect on the group-level responses. Based on the results, a final priority score was calculated for each hazard using Equation (1) [40], where n represents the total number of participating experts and k denotes each climate change-related natural hazard evaluated. In addition, the coefficient of variation (CV) and interquartile range (IQR) for likelihood and impact were analyzed to assess the stability and validity of expert assessments.

Because the Delphi method relies on experts’ subjective and intuitive judgments to produce rational results, expert selection is crucial [37,38,39,40,43,44]. Therefore, a panel of 42 nuclear power plant experts drawn from academia, research institutions, industry, and regulatory agencies was formed to evaluate the priorities of natural hazards related to climate change. The 42 experts specialize in nuclear power plant systems and safety. Table 1 summarizes the affiliations of the panel experts who participated in the survey. Figure 1 depicts the panelists’ professional backgrounds and educational qualifications. The composition of this expert panel, with its extensive experience, improved the evaluation’s reliability.

Table 1.

Summary of survey expert panels.

Figure 1.

Career and scholarship of expert panels. (a) Career of expert panels. (b) Scholarship of expert panels.

3. Identification of Natural Hazards Related to Climate Change

Identifying hazards that may affect the operation and safety of nuclear power plants, while considering Korea’s climate characteristics, is essential for assessing the prioritization of climate change-related natural hazards. For this purpose, 69 external hazards—excluding seismic hazards—were identified based on operational records from the Operational Performance Information System (OPIS) for Nuclear Power Plants and various literature sources [45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. Table 2 shows that the identified hazards were first classified into natural and anthropogenic categories, and then subdivided into atmospheric, terrestrial, and hydrological hazards [46,47]. The excluded hazards include animals, high air pollution, meteorites, soil shrink-swell, sinkholes, and heavy load drops. Table 3 lists related wind hazards, including extreme winds and tornadoes, hurricanes/typhoons, and other strong winds not classified as hurricanes or tornadoes.

Table 2.

Identification of external hazards [45,46,47,48,49,50,51].

Table 3.

Natural hazards related to climate change.

Table 3 lists natural hazards associated with climate change, some of which are unlikely to occur or may have little or no impact on nuclear power plants. Therefore, it is critical to identify and eliminate hazards that have a minimal impact on nuclear power plant operations. This filtering process involved six experts with over 25 years of experience in the safety and systems of nuclear power plants (from KAERI and KINS). Before the screening process, the experts were thoroughly briefed and engaged in a structured review of extensive reference materials to ensure consistent judgment and a solid understanding of the technical background. These materials encompassed a wide range of information relevant to evaluating climate-related natural hazards. Specifically, the experts reviewed the qualitative screening criteria outlined in EPRI 102997 (Table 4), a comprehensive list of 69 external event types, and operational experience data sourced from the Operational Performance Information System (OPIS). In addition, they examined global climate change impact assessments, including those published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), as well as national-level climate change reports issued by Korea’s Ministry of Environment and Ministry of Science and ICT. Furthermore, by reviewing the studies presented by Kim et al., 2024 [11], SKI Report 02:27 2003 [46] and Shanley and Miller 2015 [47], the experts understood how climate-induced natural hazards can affect the safety and operation of nuclear power plants. Through this preparatory process, the experts were equipped with a consistent and informed basis for identifying and excluding low-priority hazards in the context of nuclear power plant safety. Table 5 presents the excluded natural hazards related to climate change and the reasons for their exclusion. Ultimately, Table 6 shows the final list of climate change-related natural hazards for priority evaluation.

Table 4.

Recommended qualitative screening criteria [47].

Table 5.

Reasons for screening for natural hazards related to climate change.

Table 6.

List of climate change-related natural disasters that could affect nuclear power plants (priority assessment targets).

4. Priorities of Natural Hazards Related to Climate Change

4.1. Priority Results

To determine the priorities of natural hazards related to climate change that affect nuclear power plants, 42 nuclear experts participated in a Delphi survey. The Delphi survey’s first and second rounds ran from 2 July to 25 July 2024. The statistical results from the first round of the Delphi survey were presented to the experts in the second round. Table 7 and Table 8 show the results of the Delphi survey’s likelihood, impact, and priority scores for both rounds. The likelihood and impact presented in Table 7 and Table 8 are the sum of scores evaluated by 42 experts. Additionally, the prioritization results for climate change-related natural hazards are shown in terms of likelihood, impact, and priority scores.

Table 7.

Prioritization of natural hazards related to climate change using the first Delphi method.

Table 8.

Prioritization of natural hazards related to climate change using the second Delphi method.

In the first round of the survey, “extreme rain” had the highest likelihood score of 163 points and the second highest impact (Impact) score of 146 points, resulting in the highest total priority score of 583 points. Meanwhile, “extreme winds/tornadoes/hurricanes/typhoons” came in second with a likelihood score of 153 points and first with an impact score of 149 points, for a total priority score of 546 points, placing it second overall. “Biological events” and “external flooding” ranked third and fifth, respectively, with likelihood scores of 137 points and 131 points. In terms of impact, they received 142 points (fourth place) and 144 points (third place), resulting in total priority score of 477 points (third place) and 459 points (fourth place), respectively. The average, quartiles, and median values from the first round of the Delphi survey were distributed to experts in the second round.

In the second round of the Delphi survey, extreme rain came in first with a likelihood score of 166 points and third with an impact score of 152 points, maintaining the highest total priority score of 609. Meanwhile, extreme winds/tornadoes/hurricanes/typhoons ranked second with a likelihood score of 161 points and first with an impact score of 157 points, resulting in a total priority score of 606 points and second place overall. External flooding ranked third with a likelihood score of 140 points and second with an impact score of 154 points, resulting in a total priority score of 519 points and third place. Biological events came in fourth place with a likelihood score of 139 points and an impact score of 142 points, resulting in a total priority score of 481 points. Extreme rain and extreme winds/tornadoes/hurricanes/typhoons consistently ranked as the most dangerous, and the top five items remained the same in both rounds. This consistency in expert opinions demonstrates that natural hazards related to climate change are recognized as significant risks to the operation and safety of nuclear power plants.

Table 9 compares natural hazards priorities related to climate change by schools/research institutions, industries, and regulatory institutes. Except for the ranking differences for “extreme rain” and “extreme winds/tornadoes/hurricanes/typhoons,” the survey findings show that each item had a general similarity across the institutions. This suggests that experts from various institutions have a consistent view of the severity of natural hazards related to climate change.

Table 9.

Prioritization of natural hazards related to climate change by institute.

4.2. Verification and Discussion

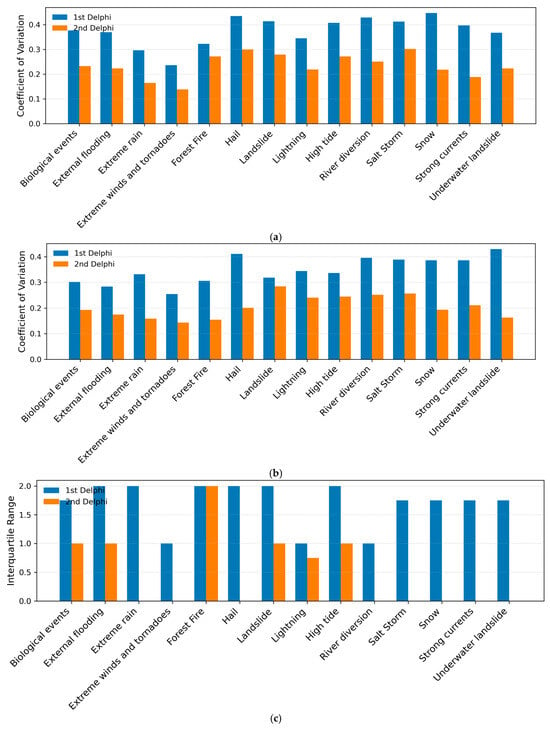

The validity, consistency, and stability of expert opinions in prioritizing natural hazards associated with climate change were evaluated using CV and IQR. Table 10 and Table 11 show the standard deviation, mean, median, IQR, and coefficient of variation (CV) for the impact and likelihood of these hazards in the first and second rounds of the Delphi survey. Figure 2 compares CV and IQR values between the first and second Delphi survey rounds, demonstrating increased stability and consensus in expert opinions. A CV value less than 0.5 typically indicates that expert opinions are stable [52]. When applying a five-point scale, an IQR of one or less suggests that respondents have reached a consensus [53]. The first Delphi survey results show that all items had CV values less than 0.5, indicating stable opinions [52]. The second Delphi survey resulted in a decrease in standard deviations, IQR, and CV values, indicating increased stability and validity in expert evaluations. The IQR and CV confirm that the prioritization of natural hazards associated with climate change was consistently based on expert opinions, thus enhancing the reliability of prioritization.

Table 10.

Results of the first Delphi survey.

Table 11.

Results of the second Delphi survey.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the CV for hazard between the 1st and 2nd Delphi survey results. (a) Comparison of the CV for hazard occurrence likelihood between the 1st and 2nd Delphi survey results. (b) Comparison of the CV for hazard impact between the 1st and 2nd Delphi survey results. (c) Comparison of the IQR for occurrence likelihood between the 1st and 2nd Delphi survey. (d) Comparison of the IQR for hazard impact between the 1st and 2nd Delphi survey results.

The BWS method validated the prioritization of natural hazards related to climate change. BWS evaluates the relative importance of alternatives by identifying the most and least important options, providing a simple and consistent response method [54,55]. The BWS survey involved 42 experts. Table 12 shows the results of comparing the priorities of natural hazards related to climate change using both the Delphi and BWS methods. Despite differences in rankings produced by the two methods, the top eight items remained consistent. This suggests that the Delphi and BWS methods complement each other in assessing the importance of natural hazards related to climate change, implying a common perception among experts.

Table 12.

Comparison of Delphi method results and BWS results.

This study collected expert opinions and identified typhoons, biological events, heavy rain, external flooding, and wildfire as the top-ranked hazards to Korean nuclear power plants. These top-ranked hazards, as confirmed by OPIS (Operational Performance Information System), have affected Korean nuclear power plants [11,45]. A journal that screened extreme natural hazards for Korean nuclear power plants evaluated internal flooding due to heavy rain, wind pressure due to strong winds, and extreme weather conditions as potential threats encountered at Korean nuclear power plant sites [56]. A Delphi-based study that analyzed the causes of large-scale power outages in the Korean transmission network identified strong winds/typhoons and heavy rain/floods as the top-ranked hazards [40]. Thus, historical records and previous studies show similar trends to the priorities derived in this study.

The impacts of climate change and the hazards faced by nuclear power plants can vary considerably across different regions due to their unique environmental and climatic conditions. For example, heat waves and elevated water temperatures have affected European nuclear power plants [11]. In contrast, hurricanes, floods, and periods of extreme cold have affected facilities in the United States [11]. This highlights the importance of tailoring risk assessments and adaptation strategies to specific regional contexts, rather than adopting a one-size-fits-all approach. The IPCC research in Figure 3 illustrates that projected climate impact indicators differ by region, including East Asia, Europe, and North America. In particular, average precipitation, river floods, fire weather, and typhoons are projected to increase in East Asia, showing a trend similar to the priority results of this study. These suggest that hazard prioritization may need to consider region-specific environmental and climatic conditions.

Figure 3.

Future climate impacts around nuclear power plants (↑: increase, ↓: decrease) [11].

In Korea, periodic safety reviews and post-Fukushima stress tests have assessed the impacts of external hazards, including those associated with climate change. However, these assessments have relied on historical data and records. Due to climate change, relying on past data may be insufficient because historical records often fail to capture new hazards or shifts in their frequency and intensity. Therefore, safety assessments should integrate future climate scenarios, such as those based on SSPs or RCPs, to account for potential changes in the frequency and intensity of climate-related hazards. In addition, given the potential for future climate change, proactive and forward-looking assessments should be considered to reassess continually and, if necessary, supplement existing safeguards.

The results can be a reference for future risk assessments and response planning. The prioritization outcomes offer a practical foundation for strengthening risk-informed decision-making in the safety planning of nuclear power plants in Korea. They can also support future vulnerability assessments, the development of adaptation strategies, and the formulation of regulatory policies that account for evolving climate-related risks.

5. Conclusions

Climate change is driving increases in atmospheric temperature, sea surface temperature, and sea level, intensifying the frequency and severity of natural hazards such as typhoons, extreme rainfall, and forest fires. These climate-related hazards pose significant risks to nuclear power plants’ safe and reliable operation. Therefore, identifying and prioritizing these hazards is essential for effective risk management and safety planning.

This study identified climate change-related natural hazards affecting nuclear power plants in Korea by gathering expert opinions and evaluating the likelihood and impact of each hazard. The results showed that extreme rainfall, typhoons, external flooding, biological events, and forest fires were consistently classified as high-risk hazards. The rankings were generally consistent across experts from different sectors, including research institutes, industry, regulatory agencies, and academia. This consistency reinforces the credibility of the prioritization results and demonstrates a shared understanding of key risks across institutional boundaries.

The prioritization outcomes offer practical value for enhancing preparedness measures and supporting risk-informed decision-making. They can guide the efficient allocation of resources and serve as a reference for developing climate adaptation strategies for nuclear power plant operations. While the Delphi method is qualitative, consensus among expert opinions was confirmed using the coefficient of variation (CV), and applying the best–worst scaling (BWS) method provided cross-validation, thereby enhancing the robustness of the results.

This methodology relies on expert judgment and does not incorporate complementary quantitative modeling or scenario-based simulations. Future research can enhance analytical rigor and support a more evidence-based hazard prioritization by integrating probabilistic risk models and climate projection data. Moreover, since the findings reflect expert input and climate conditions specific to Korea, their applicability to other geographical contexts may be limited. When applying this methodology internationally, researchers should consider regional differences in hazard profiles, regulatory frameworks, and expert perspectives. For example, while Korea prioritizes extreme rainfall and typhoons, several nuclear power plants in Europe have shut down due to high ambient temperatures. These differences highlight the importance of accounting for regional climatic and environmental conditions in hazard prioritization. Future studies should adapt and apply this approach across regions through international collaboration to enable comparative analysis and improve the generalizability of the results.

Nuclear power plants must integrate climate risk into their safety and operational frameworks as climate change accelerates. This includes updating design bases to reflect projected hazards due to climate change, considering multi-hazard and cascading scenarios, and continuously improving hazard prediction models. Strengthening the predictive capabilities of climate impact assessments and adopting forward-looking policies will be essential for ensuring the long-term resilience of the nuclear sector under evolving environmental conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.E.; methodology, S.E. and D.K.; investigation, D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.K. and S.E.; writing—review and editing, S.E., S.K., M.K. and R.J.; visualization, D.K. and S.E.; supervision, S.E.; project administration, D.K., S.K., M.K., R.J. and S.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean Government (Ministry of Science and ICT) (No. RS-2022-00154571). And This work was supported by the Nuclear Safety Research Program through the Korea Foundation Of Nuclear Safety (KoFONS) using the financial resource granted by the Nuclear Safety and Security Commission (NSSC) of the Republic of Korea (RS-2024-00404119).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

- World Meteorological Association. State of the Global Climate 2023; WMO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; 3056p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Aalst, M.K. The impacts of climate change on the risk of natural disasters. Disasters 2006, 30, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, J.E.; Ballinger, T.J.; Euskirchen, E.S.; Hanna, E.; Mård, J.; Overland, J.E.; Tangen, H.; Vihma, T. Extreme weather and climate events in northern areas: A review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 209, 103324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banholzer, S.; Kossin, J.; Donner, S. The impact of climate change on natural disasters. In Reducing Disaster: Early Warning Systems for Climate Change; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 21–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kotz, M.; Levermann, A.; Wenz, L. The economic commitment of climate change. Nature 2024, 628, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Meteorological Administration. 2023 Abnormal Climate Report; Korea Meteorological Administration: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Taye, M.T.; Dyer, E. Hydrologic Extremes in a Changing Climate: A Review of Extremes in East Africa. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2024, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Calvin, K.; Dasgupta, D.; Krinner, G.; Mukherji, A.; Thorne, P.; Trisos, C.; Romero, J.; Aldunce, P.; Barrett, K.; et al. IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report, Summary for Policymakers. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Katona, T.J. Natural hazards and nuclear power plant safety. In Natural Hazards-Risk, Exposure, Response, and Resilience; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Kwag, S.; Hahm, D.; Kim, J.; Eem, S. Investigating Natural Disaster-Related External Events at Nuclear Power Plants: Towards Climate Change Resilience. Int. J. Energy Res. 2024, 2024, 3921093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostadinov, V. Developing new methodology for nuclear power plants vulnerability assessment. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2011, 241, 950–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.; Ha, J.G.; Hahm, D.; Kim, M.K. A review of multihazard risk assessment: Progress, potential, and challenges in the application to nuclear power plants. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 53, 101933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 10 CFR 50; Appendix A, General Design Criteria for Nuclear Power Plants. Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2011.

- IAEA. Design of Nuclear Installations Against External Events Excluding Earthquakes; IAEA Specific Safety Guide No. SSG-68; International Atomic Energy Agency: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- EPRI. Climate Vulnerability Assessment Guidance for Nuclear Power Plants; Electric Power Research Institute: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2022; Product ID 3002023814. [Google Scholar]

- EPRI. Climate Vulnerability Considerations for the Power Sector: Nuclear Generation Assets; Electric Power Research Institute: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2023; Product ID 3002026313. [Google Scholar]

- Lidskog, R.; Sjödin, D. Extreme events and climate change: The post-disaster dynamics of forest fires and forest storms in Sweden. Scand. J. For. Res. 2016, 31, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietäväinen, H.; Johansson, M.; Saku, S.; Gregow, H.; Jylhä, K. Extreme weather, sea level rise and nuclear power plants in the present and future climate in Finland. In Proceedings of the 11th International Probabilistic Safety Assessment and Management Conference and the Annual European Safety and Reliability Conference 2012 (PSAM11 ESREL 2012), Helsinki, Finland, 25–29 June 2012; pp. 5487–5496. [Google Scholar]

- Energiforsk. The Impact of Climate Change on Nuclear Power; Energiforsk: Stockholm, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chand, M.; McEntire, D. The February 2021 Winter Storm and its impact on Texas infrastructure: Lessons for communities, emergency managers, and first responders. Risk Hazards Crisis Public Policy 2024, 15, 308–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, Y. Impact of Climate Change on Thermal Power Plants. Case Study of Thermal Power Plants in France. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Iceland, Reykjavík, Iceland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rübbelke, D.; Vögele, S. Impacts of climate change on European critical infrastructures: The case of the power sector. Environ. Sci. Policy 2011, 14, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPRI. Climate Informed Planning and Adaptation for Power Sector Resilience; Electric Power Research Institute: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2023; Product ID 3002026317. [Google Scholar]

- Kopytko, N.; Perkins, J. Climate change, nuclear power, and the adaptation–mitigation dilemma. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A. Increase in frequency of nuclear power outages due to changing climate. Nat. Energy 2021, 6, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnerud, K.; Mideksa, T.K.; Eskeland, G.S. The impact of climate change on nuclear power supply. Energy J. 2011, 32, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAEA. Meteorological and Hydrological Hazards in Site Evaluation for Nuclear Installations; IAEA Safety Standards Series No. SSG-18; International Atomic Energy Agency: Vienna, Austria, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- WENRA. Guidance Document Issue TU: External Hazards Head Document; Western European Nuclear Regulators’ Association, 2020. Available online: https://www.wenra.eu/sites/default/files/publications/wenra_guidance_on_issue_tu_head_document_-2020-06-01.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- WENRA. Guidance Document Issue TU: External Hazards Guidance on Extreme Weather Conditions; Western European Nuclear Regulators’ Association, 2020. Available online: https://www.wenra.eu/sites/default/files/publications/wenra_guidance_on_extreme_weather_conditions_-_2020-06-01.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- NEA. Examination of Approaches for Screening External Hazards for Nuclear Power Plants; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ONR. Safety Assessment Principles for Nuclear Facilities; Office for Nuclear Regulation: Bootle, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- ONR. Underpinning the UK Nuclear Design Basis Criterion for Naturally Occurring External Hazards; Office for Nuclear Regulation: Bootle, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- GAO. Climate Resilience: Congressional Action Needed to Enhance Climate Economics Information and to Limit Federal Fiscal Exposure; United States Government Accountability Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tolo, S.; Patelli, E.; Beer, M. Risk assessment of spent nuclear fuel facilities considering climate change. ASCE-ASME J. Risk Uncertain. Eng. Syst. Part A Civ. Eng. 2017, 3, G4016003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.T.; Chokshi, N.C.; Kenneally, R.M.; Kelly, G.B.; Beckner, W.D.; McCracken, C.; Murphy, A.J.; Reiter, L.; Jeng, D. Procedural and Submittal Guidance for the Individual Plant Examination of External Events (IPEEE) for Severe Accident Vulnerabilities; US Nuclear Regulatory Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Avella, J.R. Delphi panels: Research design, procedures, advantages, and challenges. Int. J. Dr. Stud. 2016, 11, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linstone, H.A.; Turoff, M. (Eds.) The Delphi Method; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y.J. Understanding and Application Examples of the Delphi Technique; Regular Assignment Report; 2008; pp. 1–17. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=ko&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%EB%8D%B8%ED%8C%8C%EC%9D%B4+%EA%B8%B0%EB%B2%95%EC%9D%98+%EC%9D%B4%ED%95%B4%EC%99%80+%EC%A0%81%EC%9A%A9%EC%82%AC%EB%A1%80+-+%EC%88%98%EC%8B%9C%EA%B3%BC%EC%A0%9C%EB%B3%B4%EA%B3%A0%EC%84%9C&btnG= (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Lim, Y.B.; Kim, Y.H.; Shin, D.J. Identification of Blackout Hazards Caused by Transmission System Using the Delphi Method. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. (JEET) 2022, 263–265. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=ko&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%EB%8D%B8%ED%8C%8C%EC%9D%B4%EA%B8%B0%EB%B2%95%EC%9D%84+%ED%99%9C%EC%9A%A9%ED%95%9C+%EC%86%A1%EC%A0%84%EA%B3%84%ED%86%B5%EC%97%90+%EC%9D%98%ED%95%9C+%EA%B4%91%EC%97%AD%EC%A0%95%EC%A0%84+%EC%9A%94%EC%9D%B8%EC%9D%98+%EC%8B%9D%EB%B3%84&btnG= (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Shang, Z. Use of Delphi in health sciences research: A narrative review. Medicine 2023, 102, e32829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevelyan, E.G.; Robinson, N. Delphi methodology in health research: How to do it? Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2015, 7, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anowar, F.; Helal, M.A.; Afroj, S.; Sultana, S.; Sarker, F.; Mamun, K.A. A critical review on world university ranking in terms of top four ranking systems. In New Trends in Networking, Computing, E-Learning, Systems Sciences, and Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 559–566. [Google Scholar]

- Zakaria, M.H.; Ahmad, M.F. The Preferences Towards Local and Imported Matured Coconut Using the Delphi and AHP Approach; ETMR MARDI: Selangor, Malaysia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- OPIS. Operational Performance Information System for Nuclear Power Plant. Available online: https://opis.kins.re.kr/opis?act=KROBA3100R (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Guidance for External Events Analysis; SKI Report 02:27 (ISRN SKI-R-02/27-SE); IAEA: New York, NY, USA, 2003.

- Shanley, L.; Miller, D. Identification of External Hazards for Analysis in Probabilistic Risk Assessment; EPRI Report; EPRI: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2015; Product ID 1022997. [Google Scholar]

- Probabilistic Safety Analysis (PSA) of Other External Events Than Earthquake; NEA/CSNI/R(2009)4; CSNI WGRisk: Paris, France, 2009.

- ASME/ANS RA-Sb-2013; Addenda to ASME/ANS RA-S-2008 Standard for Level 1/Large Early Release Frequency Probabilistic Risk Assessment for Nuclear Power Plant Applications. American Society of Mechanical Engineers and American Nuclear Society: New York, NY, USA, 2013.

- US Nuclear Regulatory Commission; Office of Nuclear Reactor Regulation. Standard Review Plan for the Review of Safety Analysis Reports for Nuclear Power Plants; US Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Office of Nuclear Reactor Regulation: Rockville, MD, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Guideline for Swiss Nuclear Installations ENSI-A05/e. Probabilistic Safety Analysis (PSA): Quality and Scope; Eidgenössisches Nuklearsicherheitsinspektorat: Brugg, Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Andrades-González, I.; Molina-Mula, J. Validation of content for an app for caregivers of stroke patients through the Delphi method. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Gracht, H.A. The Future of Logistics: Scenarios for 2025; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, T.N.; Louviere, J.J.; Peters, T.J.; Coast, J. Using discrete choice experiments to understand preferences for quality of life. Variance-scale heterogeneity matters. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1957–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.S. A study on the priorities of local food purchase factors in Jeonju using Best-Worst Scaling technique. Reg. Dev. Stud. 2017, 26, 127–151. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, G.Y.; Kim, G.B.; Park, H.S.; Park, H.K.; Choun, Y.S.; Chang, S.H. Screening Cases of Potential Extreme Natural Hazards Based on External Event Analysis of Operational Nuclear Power Plants. KSCE J. Civ. Environ. Eng. Res. 2022, 43, 699–708. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).