Social Embeddedness Strategies of Sustainable Startups: Insights from an Emerging Economy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

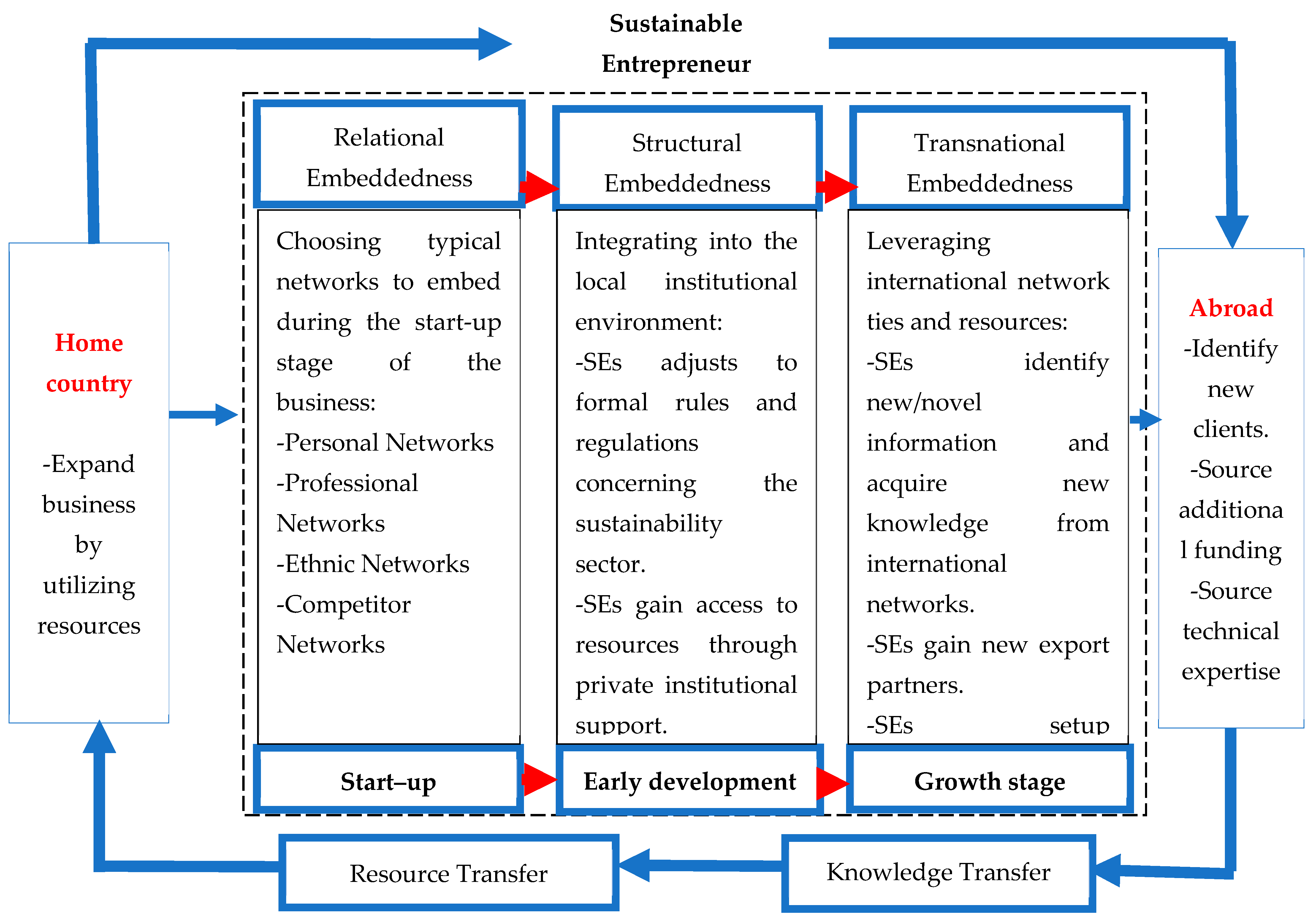

2.1. Social Embeddedness

2.2. Relational, Structural, and Transnational Embeddedness

3. Methods

3.1. Case Selection

3.2. Case Description: Overview of Case Study Firms

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Relational Embeddedness

4.1.1. Personal Networks

‘Yeah, for sure. So, the lead investors in our seed round, it was family and friends that helped. We were growing and we needed more funding, so their help came at a very critical time for us… We were doing what we call the seed round of funding, I think for us we had run a different business before, so there were so many nuances with that. I would say pre-seed, we got angel funding. So, funds in the middle kind of tied with the broader seed round that we did’.[Case G]

‘I would say when we started. That’s especially when we needed it the most right. When you start a project, you need to pay salaries, you must pay for some things. Yeah, I would say the early stages when we set out to figure out what we were trying to do and needed the resources to prove our concept. It was important to have support. I mean, it’s still important but it’s probably less financial these days’.[Case F]

‘Yes, I have received support from friends and family. So, when I wanted to enter the market in January, I got some loans from friends, like short-term loans and we’ve been able to pay most of them back. That’s how we were able to get into the market because we needed to manufacture a particular target for the economics to make sense. So, we had to source money from friends and family. Again, we went to Nigerian banks. They were not forthcoming, and this is one of the issues that Nigeria needs to address’.[Case E]

‘Yes, I have received support especially in the beginning before we got connected to the international supporters/funders. But those are casual friends whom I can easily collect small lumps and then pay back’.[Case B]

4.1.2. Professional Networks

‘Yes, of course. We have an association, the Recyclers Association of Nigeria, through which we support ourselves through information sharing, expertise, funding, and helping through challenges’.[Case B]

‘Yes, I do have an association but it’s mainly for people that are into recycling, particularly plastic recycling’.[Case A]

‘Occasionally, I like to use it to receive and disseminate information primarily. That is the purpose of what I see it as. I’m also a board member of one or two organizations, industry organizations. But yeah, primarily, in the short term, that’s what I think they are useful for and to an extent, it does the job’.[Case F]

4.1.3. Ethnic Networks

‘But when I organized a tree planting campaign some time ago, we did that there. I organize tree planting campaigns at different times and in different locations. So, on that occasion, we decided to do it in my community, and I had to reach out to them, they promised to support and well, some of them came out in person physically to join the planting’.[Case C]

‘Well, I can’t really say support, but we do business with them. They supply me with materials I need, and I pay for them, so it’s just regular business’.[Case A]

4.1.4. Competitor Networks

‘Again, we are taking a very collaborative approach, so the way we think about is they haven’t been able to effectively deploy funds into the renewable energy space and I think we’re doing a decent job with that. So, collaborating with them means they can channel funds to us’.[Case G]

‘The ultimate goal is to raise an army of like-minded individuals like when you’re all doing these things coherently, in unison. Like I tell people, as an individual, I’m like a drop of water but when we come together, we form an ocean. As an individual, my effect and impact would create a little ripple but together, we will create a wave. That’s the ultimate goal for me. To have everybody understand and embrace this as a lifestyle, culture’.[Case C]

‘I still struggle to call them my competitors because less than ten percent of the market is being collected and processed and the former market is less than half of that. So yeah, I maintain a good relationship with all of them and we are also having conversations with them around providing our solution to them as well’.[Case F]

‘I actually have about five. I have met some and even visited their crushing site. Some in Abuja, some in Kano before I set up mine’.[Case A]

‘Yes, that’s exactly how I have been able to stay afloat… Monetarily, in every way. Even the land we currently operate on, it’s my mentor (who) gave it to me. He wanted to use that place for some incineration’.[Case C]

‘So yeah, everything I know in the industry is by testing and learning and by speaking to people. So yeah, I so have some mentors’.[Case F]

4.2. Structural Embeddedness

‘I believe if we have a good relationship with those government organizations, our business will flourish more’.[Case A]

‘I think it’s definitely helpful and beneficial to have a good relationship with the government. Because one, there’s a lot of capacity that the government can make, you could also help the government see things from the private sector perspective, the government also has certain resources at their disposal including policy making that can actually expand our impact as a private sector company. So, I think whenever we can collaborate with the government, it’s more than welcoming actually’.[Case G]

‘You need to have a good relationship with regulators otherwise they shut you down. But more importantly, I said earlier that my role is to support the government especially in technology and the advancement in technology. No matter how developed we get as entrepreneurs, if the government is not aware of how to enforce or control, the impact won’t be as pronounced. So yeah, for me, with management, it is primarily local. It’s not even state or nationwide. But the point is regulators, local governments, which is local, you can’t do without them’.[Case F]

‘I remember every program, every outreach program we want to carry out, we have to write to the government. To the appropriate office, the appropriate ministry and on every occasion, they tell us that there is no fund for us, but they are giving us permission to go ahead and do it, and we will say thank you’.[Case C]

‘Not necessarily a relationship. We just want the government to do what they are supposed to do. Every other thing becomes easier’.[Case E]

‘The government policy around sustainable waste management, plastic waste collection and recycling is still being drafted…, so there was no government policy then when I initiated the business’.[Case B]

‘But for me, I would say I support the government more than the government supports me. That’s because right now, regulation in this sector is being developed and I am in a case where I might have a bit more insight than they do because of the work I do and also because of the data I have access to’.[Case F]

‘Not at all. It’s always private institutions, international organizations you know. All of the money that we’ve gotten…, from different organizations is not exactly the government giving money. And I think this is where the government needs to put in more work right. If you look at developed countries, when you want to start a business, they give you a grant to start the business whether you fail or not, they still give you the grant either way because to start a business requires so much. When you are doing well, you get access to more grants, and more loans. All of these are not accessible in Nigeria… Again (company name) didn’t just support us in the establishment of our business, but have played a huge role in helping us continue our business… So, take for example (company name) recommended us for the (name of program) Program…that knowledge transfer helped us build a second product which we will be launching shortly’.[Case E]

‘The recycling is the business and then I noticed that to get people to understand it, we need to go out and sensitize and advocate and the company cannot render those advocacy services. So, we had to set up the NGO and with the NGO, we didn’t just limit the operations and services to recycling advocacy. We organized environment documentary screenings at different places and for most of these programs and events, we’ve gotten funding… from a couple of companies’.[Case C]

4.3. Transnational Embeddedness

‘Oh yeah, I did receive that, especially expertise… my friends living abroad… So, some of them are researchers in their fields. Some of them are also environmental scientists and some of them are business consultants. So, if you have any business challenge… they can support us from there’.[Case B]

‘Yeah, exactly, one hundred percent. It has a positive impact because of course, I did a lot of experimentation. I tried to move around a bit, especially in entrepreneurship and did a few different things and even understanding that access to information is the most important thing. Like, money is not even that important. Information is the key and sometimes, without that access, you can’t do anything so yes, I realize that that is one of the privileges [of international networks] that this helps with’.[Case F]

‘We came back to Nigeria to implement right; we are still implementing, and people are still buying our product, but it is time to expand so that we can be able to augment all of these losses. The truth is that Nigeria has a big market, but the purchasing power is low. [The] UK has a smaller market, but the purchasing power is high so doing that helps us. Then, when we finish in the UK, we will spread to the US and offer our products to a specific range of people’.[Case E]

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Areas of Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kloosterman, R.; Rath, J. Immigrant entrepreneurs in advanced economies: Mixed embeddedness further explored. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2001, 27, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, J.M.; Carr, J.C.; Rasheed, A.A. Transnational entrepreneurship: Determinants of firm type and owner attributions of success. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 1023–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. Am. J. Sociol. 1985, 91, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzi, B. Social structure and competition in interfirm networks: The paradox of embeddedness. Adm. Sci. Q. 1997, 42, 35–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanyi, K. The Great Transformation: Economic and Political Origins of Our Time; Rinehart: New York, NY, USA, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Mainela, T.; Puhakka, V. Embeddedness and networking as drivers in developing an international joint venture. Scand. J. Manag. 2008, 24, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, R.; Fan, M.; Zhang, M.; Sun, H. A dynamic dual model: The determinants of transnational migrant entrepreneurs’ embeddedness in the UK. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2019, 15, 29–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Yli-Renko, H. New, technology-based firms in small open economies—An analysis based on the Finnish experience. Res. Policy 1998, 26, 973–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, E.; Cliff, J. The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: Toward a family embeddedness perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 573–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallmuenzer, A.; Peters, M. Exploring entrepreneurial orientation in family firms: The relevance of social embeddedness in competition. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2017, 30, 191–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.; Richard, W. The role of social embeddedness in professorial entrepreneurship: A comparison of electrical engineering and computer science at UC Berkeley and Stanford. Res. Policy 2004, 33, 691–707. [Google Scholar]

- Harima, K. Theorizing disembedding and re-embedding: Resource mobilization in refugee entrepreneurship. Entrep. Rural. Dev. 2022, 34, 269–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.; Stevens, C. Different types of social entrepreneurship: The role of geography and embeddedness on the measurement and scaling of social Value. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2010, 22, 575–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kistruck, M.; Beamish, P. The interplay of form, structure, and embeddedness in social intrapreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 735–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, S.; Mair, J.; Battilana, J.; Dacin, M. The Embeddedness of Social Entrepreneurship: Understanding Variation across Local Communities. In Communities and Organizations; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2011; pp. 333–363. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, B.; Winn, M.I. Market imperfections, opportunity, and sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, T.J.; McMullen, J.S. Toward a theory of sustainable entrepreneurship: Reducing environmental degradation through entrepreneurial action. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarango-Lalangui, P.; Santos, J.L.S.; Hormiga, E. The development of sustainable entrepreneurship research field. Sustain. Times 2018, 10, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, P.; Cacciotti, G.; Cohen, B. The double-edged sword of purpose-driven behavior in sustainable venturing. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 149–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salder, J. Embeddedness, values and entrepreneur decision-making: Evidence from the creative industries. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2022, 24, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshareef, S. Does location matter? Unpacking the dynamic relationship between the spatial context and embeddedness in women’s entrepreneurship. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2022, 34, 294–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufays, F. Embeddedness as a facilitator for sustainable entrepreneurship. In Sustainable Entrepreneurship and Social Innovation; Nicolopoulou, K., Karatas-Ozkan, M., Janssen, F., Jermier, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, C.; King, K.; Shipway, R. Embeddedness through sustainable entrepreneurship in events. Event Manag. 2023, 27, 1135–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welter, F. Contextualizing entrepreneurship—Conceptual challenges and ways forward. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Wright, M.; Abdelgawad, G. Contextualization and the advancement of entrepreneurship research. Int. Small Bus. J. 2014, 32, 479–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agu, A.G.; Nwachukwu, A.N. Exploring the relevance of Igbo traditional business school in the development of entrepreneurial potential and intention in Nigeria. Small Enterp. Res. 2020, 27, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDade, B.E.; Spring, A. The ‘new generation of African entrepreneurs’: Networking to change the climate for business and private sector-led development. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2005, 17, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, B. A framework for understanding the role of culture in entrepreneurship. Acta Commer. 2007, 7, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mitchell, B.C. Motives of entrepreneurs: A case study of South Africa. J. Entrep. 2004, 13, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patzelt, H.; Shepherd, D. Recognizing opportunities for sustainable development. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, S.L.; Anderson, A.R. The effects of embeddedness on the entrepreneurial process. J. Bus. Ventur. 2002, 17, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.L. Entrepreneurial networks and new organization growth. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1995, 19, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schell, D.W.; Davig, W. The community infrastructure of entrepreneurship: A sociopolitical analysis. In Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research; Vesper, K.H., Ed.; Bobson College: Babson Park, MA, USA, 1981; pp. 563–590. [Google Scholar]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi-Bosiakoh, T. Transnational embeddedness of Nigerian immigrant entrepreneurship in Ghana, West Africa. Int. Migr. Integr. 2020, 21, 1187–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Urbano, D.; Toledano, N.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D. Socio-cultural factors and transnational entrepreneurship: A multiple-case study in Spain. Int. Small Bus. J. 2011, 29, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rispal, M.; Randerson, K.; Estele, J. Investigating the usefulness of qualitative methods for entrepreneurship research. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2015, 1, 13131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hemmington, N. Sampling. In The Handbook of Contemporary Hospitality Management Research; Brotherton, B., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, C. Real World Research, 2nd ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Altinay, L.; Wang, C. Facilitating and maintaining research access into ethnic minority firms. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2009, 12, 367–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsgaard, S.; Ferguson, R.; Gaddefors, J. The best of both worlds: How rural entrepreneurs use placial embeddedness and strategic networks to create opportunities. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2015, 27, 574–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, R.E. Case Studies. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N. The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, A.; Frey, J. The interview: From structured questions to negotiated text. In Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; Denzin, N., Lincoln, Y., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2004; pp. 645–670. [Google Scholar]

- Gartner, W.B. Entrepreneurial narrative and a science of the imagination. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, C.; Howorth, D. The language of social entrepreneurs. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2008, 20, 285–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Michael, A.H. Qualitative Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen, C. Tactics of sustainable entrepreneurship: Ways of operating in the contested terrain of green architecture. J. Manag. Inq. 2023, 32, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, L.D.S.; Steinbruch, F.K. “The interviews were transcribed”, but how? Reflections on management research. RAUSP Manag. J. 2019, 54, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldana, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, K.; Gibbs, D. Rethinking green entrepreneurship –fluid narratives of the green economy. Environ. Plan. A 2016, 48, 1727–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamkole, P.; Aladejebi, O. Overcoming the challenges confronting startups in Nigeria. Eur. Bus. Manag. 2023, 9, 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, S.D.; Harima, A.; Freiling, J. Network benefits for Ghanaian diaspora and returnee entrepreneurs. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2015, 3, 95–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruthi, S. Social ties and venture creation by returnee entrepreneurs. Int. Bus. Rev. 2014, 23, 1139–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, S. The plurality of institutional embeddedness as a source of organizational attention differences. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 1543–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akande, O.; Alabi, E. Performance effect of institutional environment on entrepreneurial pursuit in Nigeria. J. Manag. Corp. Gov. 2017, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Eniola, A. Institutional Environment, Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy and Orientation for SME in Nigeria. Int. J. Eng. Manag. 2020, 4, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Borah, D.; Kim, J.; Ji, J. Internationalization of transnational entrepreneurial firms from an advanced to emerging economy: The role of transnational mixed embeddedness. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2022, 29, 707–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjo, O.; Ibrahim, M. The effect of international business on SMEs growth in Nigeria. J. Compet. 2017, 9, 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sarasvathy, S. Causation and Effectuation: Toward a Theoretical Shift from Economic Inevitability to Entrepreneurial Contingency. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drori, I.; Honig, B.; Wright, M. Transnational entrepreneurship: An emergent field of study. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 1001–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P.; Honig, B. The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 301–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, U.; Björkman, I.; Forsgren, M. Managing subsidiary knowledge creation: The effect of control mechanisms on subsidiary local embeddedness. Int. Bus. Rev. 2005, 14, 521–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Zheng, W.; Lu, J.; Liu, X.; Wright, M. Forgotten or not? Home country embeddedness and returnee entrepreneurship. J. World Bus. 2019, 54, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagwell, S. From mixed embeddedness to transnational mixed embeddedness: An exploration of Vietnamese businesses in London. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Sector | Year Founded | Job Title | Education |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case A | Recycling | 2020 | Founder | Master’s Degree |

| Case B | Recycling | 2016 | Founder/CEO | Advanced Certificate |

| Case C | Recycling | 2022 | Founder/CEO | Master’s Degree |

| Case D | Recycling | 2019 | Founder/CEO | Master’s Degree |

| Case E | Renewables | 2021 | Founder/CEO | Master’s Degree |

| Case F | Recycling | 2019 | Founder/CEO | Bachelor’s Degree |

| Case G | Renewables | 2021 | Co-Founder | Master’s Degree |

| Case H | Renewables | 2014 | Founder/CEO | Master’s Degree |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ike, D. Social Embeddedness Strategies of Sustainable Startups: Insights from an Emerging Economy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125344

Ike D. Social Embeddedness Strategies of Sustainable Startups: Insights from an Emerging Economy. Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125344

Chicago/Turabian StyleIke, Dike. 2025. "Social Embeddedness Strategies of Sustainable Startups: Insights from an Emerging Economy" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125344

APA StyleIke, D. (2025). Social Embeddedness Strategies of Sustainable Startups: Insights from an Emerging Economy. Sustainability, 17(12), 5344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125344