Behavioral Drivers of Cage Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Producers and Consumers in Kenya’s Lake Victoria Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Producer Behavioral Aspects

2.2. Consumer Behavioral Aspects

2.3. Theoretical Framework: Theory of Planned Behavior

2.4. Conceptual Framework

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Study Area

3.3. Sampling Procedure

3.4. Sampling Technique

3.5. Data Collection Methods

3.6. Data Analysis Framework

3.6.1. Preliminary Analysis

3.6.2. Inferential Statistics

3.6.3. Model Specification

3.6.4. Model Fit Assessment

3.7. Measurement Scales

4. Results for Producers

4.1. Model Fit Indices for Producers

4.2. Convergent Validity for Producers

4.3. Discriminant Validity for Producers

4.4. Producer Path Analysis

4.5. Covariance Between Latent Variables

4.6. Discussion

5. Consumers’ Results

5.1. Model Fit Indices for Consumers

5.2. Factor Loadings for Consumers

5.3. Convergent Validity for Consumers

5.4. Discriminant Validity for Consumers

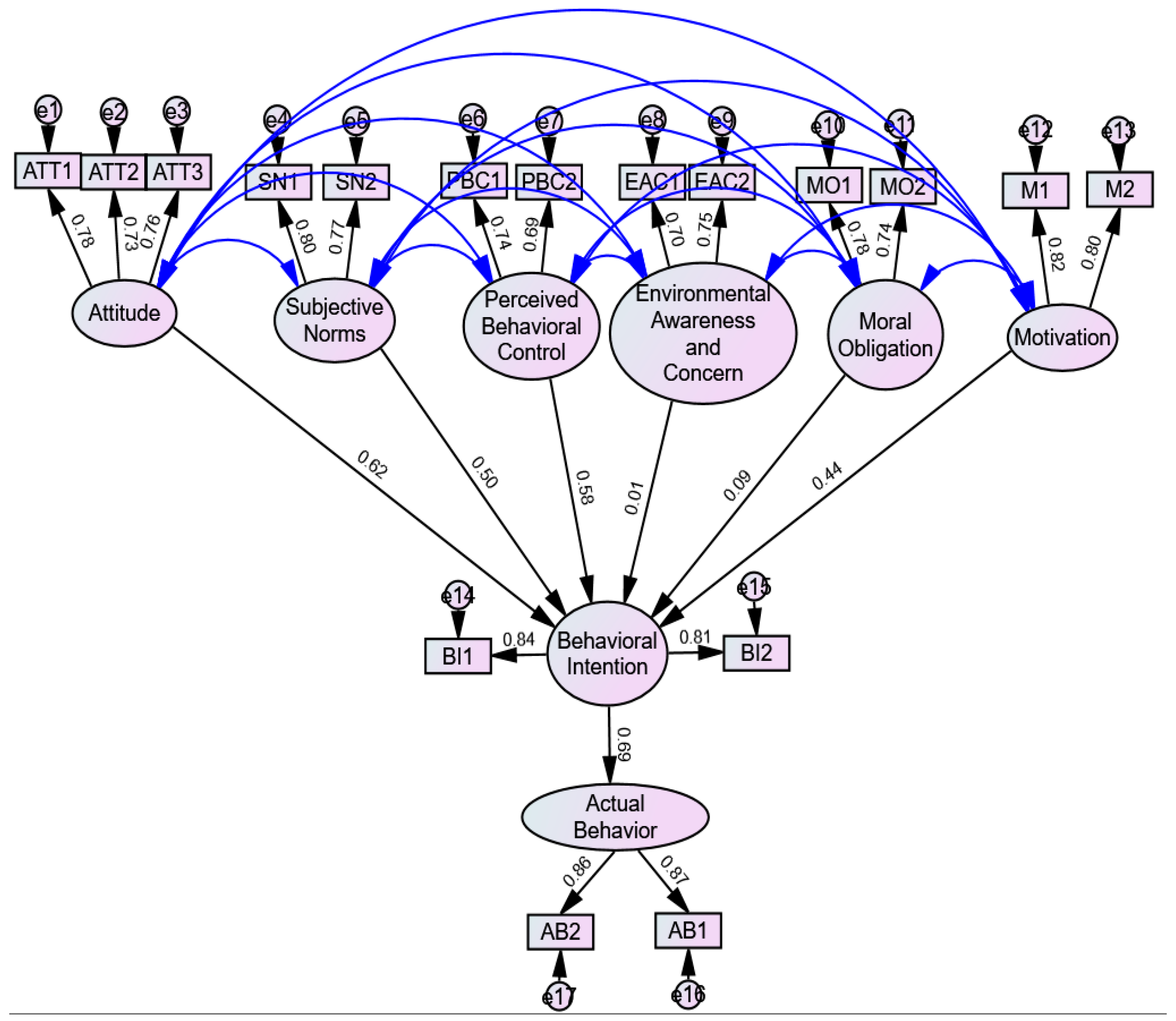

5.5. Path Analysis for Consumers

5.6. Covariance Between Latent Variables for Consumers

5.7. Discussion

6. Summary of the Findings

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Measurement of Variables

Appendix A.1. Producers

| Variable | Indicator | Measurement Questions | Response Scale | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | ATT1 | Interest in Production | You are interested in cage tilapia production. | 1–5 |

| ATT2 | Capital Intensity | Cage tilapia production is capital intensive. | 1–5 | |

| ATT3 | Technical Skills | Cage tilapia production requires technical skills on aquaculture. | 1–5 | |

| ATT4 | Sustainability | Cage culture system is a sustainable tilapia culture system in Kenya’s Lake Victoria. | 1–5 | |

| ATT5 | Profitability | When properly managed, cage tilapia production is a profitable venture. | 1–5 | |

| ATT6 | Mentorship | Cage tilapia investment requires mentorship. | 1–5 | |

| ATT7 | Government Responsibility | The Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries should be responsible for citing and marketing of cage tilapia. | 1–5 | |

| Subjective Norm | SN1 | Farmers’ Losses | Most cage tilapia farmers stopped farming due to losses. | 1–5 |

| SN2 | Profitability Concerns | Cage tilapia production is not profitable. | 1–5 | |

| SN3 | Challenges | Cage tilapia production is full of challenges. | 1–5 | |

| SN4 | Socioeconomic Status | Cage tilapia farming is for the rich and non-local residents. | 1–5 | |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | PBC1 | Skill Improvement | You have improved on cage tilapia culture over time. | 1–5 |

| PBC2 | Ease of Production | It is quite easy for you to produce cage tilapia. | 1–5 | |

| PBC3 | Knowledge Barriers | Inadequate knowledge and technical skills make cage tilapia farming difficult for me. | 1–5 | |

| Environmental Awareness and Concern | EAC1 | Certified Inputs | I feel disappointed when I don’t use certified inputs in cage culture. | 1–5 |

| EAC2 | Pollution Threat | The continued expansion of cage culture system is a potential pollution threat in Lake Victoria if not controlled. | 1–5 | |

| EAC3 | Community Conflicts | Failure to properly control siting for cages in the lake could lead to conflict between the community and investors. | 1–5 | |

| EAC4 | Satisfaction with Inputs | I feel satisfied when I use certified inputs in cage tilapia farming. | 1–5 | |

| Moral Obligation | MO1 | Guilt Over Waste | I feel guilty if I dump recyclable cage construction materials after harvesting. | 1–5 |

| MO2 | Duty to Preserve | I take it as my duty to preserve the aquatic environment. | 1–5 | |

| MO3 | Sensitivity to Aquatic Life | If every cage tilapia farmer were sensitive to aquatic life, we would not be worried about pollution in Lake Victoria. | 1–5 | |

| MO4 | Role in Pollution Control | Every cage tilapia farmer has a role to play in controlling Lake water pollution through the utilization of environmentally friendly inputs. | 1–5 | |

| MO5 | Resource Utilization | My religion encourages prudent utilization of resources. | 1–5 | |

| MO6 | Peace in Management | I usually feel at peace when I manage the cages efficiently. | 1–5 | |

| Motivation | M1 | Quality Protein | In my household, cage tilapia is a source of quality protein. | 1–5 |

| M2 | Setting Examples | By taking cage tilapia production as an economic activity, we set a good example to other fisher folk who are yet to embrace it. | 1–5 | |

| M3 | Seriousness About Farming | Having had challenges with a source of income, I take cage tilapia farming very seriously. | 1–5 | |

| M4 | Planning More Cages | My household is planning to install more cages in the lake as a result of increased profits from previous harvests. | 1–5 | |

| M5 | Major Investment | My household has focused on cage tilapia farming as a major investment. | 1–5 | |

| M6 | Profitability Compared to Wild | I embrace cage tilapia farming since it’s more profitable and predictable than wild capture systems. | 1–5 | |

| Behavioral Intention | BI1 | Direct Selling Intent | I plan to sell directly to institutions. | 1–5 |

| BI2 | Further Training | I plan to go for further training on cage culture production. | 1–5 | |

| BI3 | Contracting Traders | I plan to sign a contract with traders or processors. | 1–5 | |

| BI4 | Export Intent | I intend to export cage tilapia in the future. | 1–5 | |

| BI5 | Input Supplier Contracts | I intend to have a contract with input suppliers so that I don’t have to buy inputs in cash. | 1–5 | |

| BI6 | Increasing Cage Installation | I plan to install more cages in the lake every year. | 1–5 | |

| BI7 | Diversification Intent | I plan to diversify into other investment opportunities. | 1–5 | |

| Actual Behavior | AB1 | Sorting and Grading | I always sort and grade the cage tilapia after harvesting and price them accordingly. | 1–5 |

| AB2 | Household Consumption | I regularly eat cage tilapia in my household. | 1–5 | |

| AB3 | Seeking Extension Services | I regularly seek extension services from government fisheries officers. | 1–5 | |

| AB4 | Administering Veterinary Drugs | I always ensure that I administer veterinary drugs as instructed by the expert. | 1–5 | |

| AB5 | Direct Selling | I sometimes sell cage tilapia directly to consumers. | 1–5 | |

| AB6 | Donations | I sometimes give out cage tilapia as a tithe/offertory to the church. | 1–5 |

Appendix A.2. Consumers

| Variable | Indicator | Measurement Questions | Response Scale | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | ATT1 | Nutritional Value | Cage tilapia is tasty and nutritious. | 1–5 |

| ATT2 | Health Perception | Cage tilapia is not healthy. | 1–5 | |

| ATT3 | Price Perception | I think cage tilapia is expensive. | 1–5 | |

| ATT4 | Interest in Consumption | I am interested in cage tilapia consumption. | 1–5 | |

| ATT5 | Perceived Cost | I think cage tilapia is cheap. | 1–5 | |

| ATT6 | Availability | Cage tilapia is nowadays readily available in fish markets. | 1–5 | |

| ATT7 | Taste Comparison | Cage tilapia is not as tasty as wild-caught tilapia. | 1–5 | |

| Subjective Norm | SN1 | Economic Status of Consumers | Majority of the cage tilapia consumers are poor. | 1–5 |

| SN2 | Market Perception | Cage tilapia is referred to as “China Fish.” | 1–5 | |

| SN3 | Consumption Pattern | Cage tilapia is for mass consumption. | 1–5 | |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | PBC1 | Consumption Improvement | I have improved on cage tilapia consumption over time. | 1–5 |

| PBC2 | Ease of Consumption | It is quite easy for me to consume cage tilapia. | 1–5 | |

| PBC3 | Information Barriers | Inadequate information makes cage tilapia consumption difficult for me. | 1–5 | |

| Environmental Awareness and Concern | EAC1 | Nutritional Benefits | Cage tilapia has nutritional benefits. | 1–5 |

| EAC2 | Environmental Concerns | The foul smell from fish markets is an environmental concern. | 1–5 | |

| EAC3 | Health Risks | Displaying cage tilapia by the roadside exposes consumers to health risks. | 1–5 | |

| EAC4 | Waste Concerns | I feel disappointed when I throw edible parts of cooked cage tilapia away. | 1–5 | |

| EAC5 | Satisfaction with Consumption | I feel satisfied when I consume all the edible parts of cage tilapia. | 1–5 | |

| Moral Obligation | MO1 | Guilt Over Waste | I feel guilty if I don’t consume the entire cage tilapia that I bought. | 1–5 |

| MO2 | Support for Farmers | I feel obliged to promote our cage tilapia farmers by buying and consuming cage tilapia. | 1–5 | |

| MO3 | Preparation Guilt | I feel guilty if I don’t prepare cage tilapia properly for my household consumption. | 1–5 | |

| MO4 | Ambassadorial Role | I feel good when I am an ambassador of cage tilapia consumption. | 1–5 | |

| MO5 | Religious Influence | My religion encourages efficient consumption of food (cage tilapia inclusive). | 1–5 | |

| MO6 | Peace in Purchasing | I usually feel at peace when I buy fresh tilapia from the producer. | 1–5 | |

| Motivation | M1 | Protein Source | In my household, we consume cage tilapia as a source of quality protein. | 1–5 |

| M2 | Affordability | Cage tilapia is affordable. | 1–5 | |

| M3 | Availability | Cage tilapia is always available in plenty. | 1–5 | |

| M4 | Size Uniformity | Cage tilapia has uniform sizes. | 1–5 | |

| M5 | Cooking Qualities | Cage tilapia is soft, tasty and cooks faster. | 1–5 | |

| M6 | Feed Knowledge | I prefer cage tilapia since they feed on known feeds. | 1–5 | |

| Behavioral Intention | BI1 | Increase Intake | I intend to increase my intake of cage tilapia. | 1–5 |

| BI2 | Gather Information | I plan to gather more consumer information regarding cage tilapia. | 1–5 | |

| BI3 | Develop Network | I intend to develop a network of cage tilapia consumers. | 1–5 | |

| BI4 | Buy Processed | I intend to buy processed cage tilapia due to time constraints. | 1–5 | |

| BI5 | Contract Trader | I intend to have a contract with the trader for regular delivery of cage tilapia. | 1–5 | |

| BI6 | Diversify Consumption | I plan to diversify into consuming other types of fish as well. | 1–5 | |

| Actual Behavior | AB1 | Largest Consumption | I always consume the biggest cage tilapia | 1–5 |

| AB2 | Household Eating | I regularly eat cage tilapia cooked in my household. | 1–5 | |

| AB3 | Specific Traders | I regularly buy from specific traders/producers of cage tilapia. | 1–5 | |

| AB4 | Price Sensitivity | I’m always price-sensitive when buying cage tilapia. | 1–5 | |

| AB5 | Quality Focus | I’m always keen on quality when buying cage tilapia. | 1–5 | |

| AB6 | Personal Buying | I always buy cage tilapia personally since I do not trust traders. | 1–5 | |

| AB7 | Freshness Check | I always buy fresh cage tilapia since I can easily identify if it has gone bad. | 1–5 | |

| AB8 | Color Consideration | I consider the color of fresh cage tilapia before buying. | 1–5 |

References

- Naylor, R.L.; Hardy, R.W.; Buschmann, A.H.; Bush, S.R.; Cao, L.; Klinger, D.H.; Little, D.C.; Lubchenco, J.; Shumway, S.E.; Troell, M. A 20-year retrospective review of global aquaculture. Nature 2021, 591, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.K.; Mandal, A. Diversification in aquaculture resources and practices for smallholder farmers. In Agriculture, Livestock Production and Aquaculture: Advances for Smallholder Farming Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 263–286. [Google Scholar]

- Munguti, J.M.; Obiero, K.O.; Iteba, J.O.; Kirimi, J.G.; Kyule, D.N.; Orina, P.S.; Githukia, C.M.; Outa, N.; Ogello, E.O.; Tanga, C.M.; et al. Role of multilateral development organizations, public and private investments in aquaculture subsector in Kenya. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1208918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyakeya, K.; Masese, F.O.; Gichana, Z.; Nyamora, J.M.; Getabu, A.; Onchieku, J.; Odoli, C.; Nyakwama, R. Cage farming in the environmental mix of Lake Victoria: An analysis of its status, potential environmental and ecological effects and a call for sustainability. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2022, 25, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongprawmas, R.; Sogari, G.; Gai, F.; Parisi, G.; Menozzi, D.; Mora, C. How information influences consumers’ perception and purchasing intention for farmed and wild fish. Aquaculture 2022, 547, 737504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, J.R.; Mauad, J.R.C.; De Faria Domingues, C.H.; Marques, S.C.C.; Borges, J.A.R. Understanding the intention of smallholder farmers to adopt fish production. Aquac. Rep. 2020, 17, 100308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swami, D.; Parthasarathy, D. A multidimensional perspective to farmers’ decision making determines the adaptation of the farming community. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 264, 110487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Khatun, M.N.; Prodhan, M.M.H.; Khan, M.A. Consumer preference, willingness to pay and the market price of capture and culture fish: Do their attributes matter? Aquaculture 2021, 544, 737139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, D.; De Gennaro, B.; Materia, V.C. Cultural influences on seafood consumption: A cross-country analysis. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 104, 104729. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, N.; Li, C.; Khan, A.; Qalati, S.A.; Naz, S.; Rana, F. Purchase intention toward organic food among young consumers using theory of planned behavior: Role of environmental concerns and environmental awareness. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021, 64, 796–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orinda, M.; Okuto, E.; Abwao, M. Cage fish culture in the lake victoria region: Adoption determinants, challenges and opportunities. Int. J. Fish. Aquac. 2021, 13, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Musa, S.; Aura, C.M.; Okechi, J.K. Economic analysis of tilapia cage culture in Lake Victoria using different cage volumes. J. Appl. Aquac. 2022, 34, 674–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Drakou, E.G. Farmers intention to adopt sustainable agriculture hinges on climate awareness: The case of Vietnamese coffee. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 303, 126828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crona, B.; Nyström, M.; Folke, C.; Jiddawi, N. Microeconomic relationships between and among fishers and traders influence the ability to respond to social-ecological changes in a small-scale fishery. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Serebrennikov, D.; Thorne, F.; Kallas, Z.; McCarthy, S.N. Factors influencing adoption of sustainable farming practices in Europe: A systemic review of empirical literature. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemtou, M.; Kakkavou, K.; Anastasiou, E.; Fountas, S.; Pedersen, S.M.; Isakhanyan, G.; Erekalo, K.T.; Pazos-Vidal, S. Farmers’ Transition to Climate-Smart Agriculture: A Systematic Review of the Decision-Making Factors Affecting Adoption. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.L.H.; Khuu, D.T.; Halibas, A.; Nguyen, T.Q. Factors that influence the intention of smallholder rice farmers to adopt cleaner production practices: An empirical study of precision agriculture adoption. Eval. Rev. 2024, 48, 692–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, R.D.C.L.; Vilas Boas, L.H.D.B.; Rezende, D.C.D.; Botelho, D. Food safety and consumption of fruits and vegetables at local markets: A means-end chain approach. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2024, 27, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiyama, R.; Wakamatsu, H.; Seko, T.; Ishihara, K. Consumer preference for label presentations of freshness, taste and serving suggestion on fresh fish packages of Japanese flounder Paralichthys olivaceus. Fish. Sci. 2024, 90, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.Z.; Sultana, N.; Haque, A.; Foisal, M.T.M. Personal and socioeconomic factors affecting perceived knowledge of farmed fish. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 8, 100310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniehotta, F.F.; Presseau, J.; Araújo-Soares, V. Time to retire the theory of planned behaviour. Health Psychol. Rev. 2014, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aminizadeh, M.; Mohammadi, H.; Karbasi, A.; Rafiee, H. Predicting consumers’ intention towards seafood products: An extended theory of planned behavior. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 113, 105061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Liu, M.; Yang, Y.; Ma, W. Understanding Chinese consumers’ purchase intention towards traceable seafood using an extended Theory of Planned Behavior model. Mar. Policy 2022, 137, 104973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Cheung, M.W.L.; Ajzen, I.; Hamilton, K. Perceived behavioral control moderating effects in the theory of planned behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2022, 41, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhujel, R.R.; Joshi, H.G. Understanding farmers’ intention to adopt sustainable agriculture in Sikkim: The role of environmental consciousness and attitude. Cogent Food Agric. 2023, 9, 2261212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.; Gaskell, P.; Ingram, J.; Dwyer, J.; Reed, M.; Short, C. Engaging farmers in environmental management through a better understanding of behaviour. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 34, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W.; Vackier, I. Individual determinants of fish consumption: Application of the theory of planned behaviour. Appetite 2005, 44, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, J.A.; Georgianna, T.D. Analysis of statistical outliers with application to whole effluent toxicity testing. Water Environ. Res. 2001, 73, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejos, T.; Engler, A.; Nahuelhual, L.; Gelcich, S. From past behavior to intentions: Using the theory of planned behavior to explore noncompliance in small-scale fisheries. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2023, 239, 106615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, M.; Masud, M.M.; Alam, L.; Mokhtar, M.B.; Amir, A.A. The adaptation behaviour of marine fishermen towards climate change and food security: An application of the theory of planned behaviour and health belief model. Sustainability 2002, 14, 14001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leocádio, Á.L.; de Amorim, L.S.; Matias, J.F.N.; Guimarães, D.B.; de Mesquita Facundo, G.; da Costa Filho, N.B. Use of planned behavior for analysis of an explanatory model of fish consumption intention. Cad. Pedagógico 2024, 21, e5247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchettini, G.; Castellini, G.; Graffigna, G.; Hung, Y.; Lambri, M.; Marques, A.; Perrella, F.; Savarese, M.; Verbeke, W.; Capri, E. Assessing consumers’ attitudes, expectations and intentions towards health and sustainability regarding seafood consumption in Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 789, 148049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conner, M.; Armitage, C.J. Extending the theory of planned behavior: A review and avenues for further research. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 28, 1429–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugere, C.; Padmakumar, K.P.; Leschen, W.; Tocher, D.R. What influences the intention to adopt aquaculture innovations? Concepts and empirical assessment of fish farmers’ perceptions and beliefs about aquafeed containing non-conventional ingredients. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2021, 25, 339–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Category | Variables | Measurement Approach | Scale | Number of Questions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | Attitude | Likert scale measuring interest and perceptions | 5-point Likert scale | 7 |

| Subjective Norm | Likert scale measuring peer influence and norms | 5-point Likert scale | 4 | |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | Likert scale measuring confidence and access | 5-point Likert scale | 3 | |

| Environmental Awareness and Concern | Likert scale measuring awareness of impact | 5-point Likert scale | 2 | |

| Moral Obligation | Likert scale measuring sense of responsibility | 5-point Likert scale | 2 | |

| Motivation | Likert scale measuring desire for improvement | 5-point Likert scale | 2 | |

| Dependent Variables | Behavioral Intention | Likert scale measuring intention to adopt practices | 5-point Likert scale | 2 |

| Actual Behavior | Likert scale measuring frequency of engagement | 5-point Likert scale | 2 |

| Latent Variable | Indicator Label | Indicator Description | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | ATT1 | Interest in Cage Tilapia Farming | 0.76 |

| ATT2 | Perceived Profitability | 0.72 | |

| ATT3 | Technical Skills | 0.69 | |

| ATT4 | Sustainability of Cage Farming | 0.65 | |

| Subjective Norm | SN1 | Peer Influence | 0.78 |

| SN2 | Community Expectations | 0.74 | |

| SN3 | Recommendations from Other Farmers | 0.7 | |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | PBC1 | Confidence in Managing Operations | 0.8 |

| PBC2 | Access to Resources | 0.77 | |

| PBC3 | Knowledge of Cage Farming Techniques | 0.72 | |

| Environmental Awareness and Concern | EAC1 | Awareness of Environmental Impact | 0.74 |

| EAC2 | Concerns about Pollution | 0.71 | |

| Moral Obligation | MO1 | Sense of Responsibility toward Sustainable Practices | 0.79 |

| MO2 | Guilt over Environmental Neglect | 0.76 | |

| Motivation | MOT1 | Desire to Improve Farming Practices | 0.82 |

| MOT2 | Economic Incentives | 0.8 | |

| Behavioral Intention | BI1 | Intention to Adopt New Practices | 0.85 |

| BI2 | Willingness to Expand Operations | 0.83 | |

| Actual Behavior | AB1 | Actual Adoption of Cage Farming Practices | 0.88 |

| AB2 | Frequency of Engagement in Farming Activities | 0.86 |

| Fit Index | Value | Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-Square (χ2) | 130.25 | p < 0.01 | Indicates overall model fit |

| Degrees of Freedom (df) | 65 | - | - |

| Chi-Square/df | 2 | <3 | Acceptable fit |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | 0.05 | <0.08 | Good fit |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.94 | >0.90 | Good fit |

| Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) | 0.93 | >0.90 | Good fit |

| Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) | 0.07 | <0.08 | Acceptable fit |

| Latent Variable | Indicator Count | AVE | Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | 4 | 0.6 | ≥0.5 | Convergent validity confirmed |

| Subjective Norm | 3 | 0.55 | ≥0.5 | Convergent validity confirmed |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | 3 | 0.62 | ≥0.5 | Convergent validity confirmed |

| Environmental Awareness and Concern | 2 | 0.57 | ≥0.5 | Convergent validity confirmed |

| Moral Obligation | 2 | 0.65 | ≥0.5 | Convergent validity confirmed |

| Motivation | 2 | 0.7 | ≥0.5 | Convergent validity confirmed |

| Latent Variable | Attitude | Subjective Norm | Perceived Behavioral Control | Environmental Awareness and Concern | Moral Obligation | Motivation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | 0.78 | 0.35 | 0.42 | 0.3 | 0.38 | 0.45 |

| Subjective Norm | 0.74 | 0.4 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.41 | |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | 0.79 | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.44 | ||

| Environmental Awareness and Concern | 0.76 | 0.48 | 0.46 | |||

| Moral Obligation | 0.81 | 0.5 | ||||

| Motivation | 0.84 |

| Path | Estimate | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude→Behavioral Intention | 0.65 | <0.001 | Significant |

| Subjective Norm→Behavioral Intention | 0.59 | <0.001 | Significant |

| Perceived Behavioral Control→Behavioral Intention | 0.6 | <0.001 | Significant |

| Environmental Awareness→Behavioral Intention | 0.52 | <0.01 | Significant |

| Moral Obligation→Behavioral Intention | 0.53 | <0.01 | Significant |

| Motivation→Behavioral Intention | 0.58 | <0.01 | Significant |

| Behavioral Intention→Actual Behavior | 0.79 | <0.001 | Significant |

| Latent Variable Pair | Covariance Estimate |

|---|---|

| Attitude↔Subjective Norm | 0.35 |

| Attitude↔Perceived Behavioral Control | 0.42 |

| Attitude↔Environmental Awareness and Concern | 0.3 |

| Attitude↔Moral Obligation | 0.38 |

| Attitude↔Motivation | 0.45 |

| Attitude↔Behavioral Intention | 0.65 |

| Subjective Norm↔Perceived Behavioral Control | 0.4 |

| Subjective Norm↔Environmental Awareness and Concern | 0.33 |

| Subjective Norm↔Moral Obligation | 0.37 |

| Subjective Norm↔Motivation | 0.41 |

| Subjective Norm↔Behavioral Intention | 0.59 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control↔Environmental Awareness and Concern | 0.36 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control↔Moral Obligation | 0.39 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control↔Motivation | 0.44 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control↔Behavioral Intention | 0.6 |

| Environmental Awareness and Concern↔Moral Obligation | 0.48 |

| Environmental Awareness and Concern↔Motivation | 0.46 |

| Environmental Awareness and Concern↔Behavioral Intention | 0.52 |

| Moral Obligation↔Motivation | 0.5 |

| Moral Obligation↔Behavioral Intention | 0.53 |

| Motivation↔Behavioral Intention | 0.58 |

| Behavioral Intention↔Actual Behavior | 0.79 |

| Hypothesis | Hypothesis Description | Results |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | A positive attitude significantly influences behavioral intentions. | Supported |

| H2 | Subjective norms positively affect behavioral intentions. | Supported |

| H3 | Perceived behavioral control positively impacts behavioral intentions. | Supported |

| H4 | Motivation positively influences behavioral intentions. | Supported |

| H5 | Moral obligation positively affects behavioral intentions. | Supported |

| H6 | Environmental awareness positively influences behavioral intentions. | Supported |

| H7 | Behavioral intentions significantly influence actual behavior. | Supported |

| Fit Index | Value | Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-Square (χ2) | 112.8 | p < 0.01 | Indicates overall fit |

| Degrees of Freedom (df) | 168 | - | - |

| Chi-Square/df | 0.67 | <3 | Acceptable fit |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | 0.04 | <0.08 | Good fit |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.95 | >0.90 | Good fit |

| Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) | 0.94 | >0.90 | Good fit |

| Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) | 0.06 | <0.08 | Acceptable fit |

| Latent Variable | Indicator Label | Indicator Description | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | ATT1 | Interest in Consumption | 0.78 |

| ATT2 | Health Perception | 0.73 | |

| ATT3 | Nutritional Value | 0.76 | |

| Subjective Norm | SN1 | Economic Status Influence | 0.8 |

| SN2 | Market Perception (“China Fish”) | 0.77 | |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | PBC1 | Ease of Consumption | 0.74 |

| PBC2 | Information Barriers | 0.69 | |

| Environmental Awareness and Concern | EAC1 | Health Risks Associated with Sales Practices | 0.7 |

| EAC2 | Waste Concerns | 0.75 | |

| Moral Obligation | MO1 | Support for Local Farmers | 0.78 |

| MO2 | Ambassadorial Role | 0.74 | |

| Motivation | M1 | Cage Tilapia as a Protein Source | 0.82 |

| M2 | Affordability | 0.8 | |

| Behavioral Intention | BI1 | Intent to Increase Intake | 0.84 |

| BI2 | Gathering More Information | 0.81 | |

| Actual Behavior | AB1 | Largest Cage Tilapia Consumption | 0.87 |

| AB2 | Regular Household Consumption | 0.86 |

| Latent Variable | Indicator Count | AVE | Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | 3 | 0.64 | ≥0.5 | Convergent validity confirmed |

| Subjective Norm | 2 | 0.62 | ≥0.5 | Convergent validity confirmed |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | 2 | 0.6 | ≥0.5 | Convergent validity confirmed |

| Environmental Awareness and Concern | 2 | 0.65 | ≥0.5 | Convergent validity confirmed |

| Moral Obligation | 2 | 0.62 | ≥0.5 | Convergent validity confirmed |

| Motivation | 2 | 0.68 | ≥0.5 | Convergent validity confirmed |

| Behavioral Intention | 2 | 0.7 | ≥0.5 | Convergent validity confirmed |

| Actual Behavior | 2 | 0.75 | ≥0.5 | Convergent validity confirmed |

| Latent Variable | Attitude | Subjective Norm | Perceived Behavioral Control | Environmental Awareness | Moral Obligation | Motivation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.42 |

| Subjective Norm | 0.79 | 0.35 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.4 | |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | 0.77 | 0.4 | 0.38 | 0.41 | ||

| Environmental Awareness and Concern | 0.81 | 0.45 | 0.46 | |||

| Moral Obligation | 0.78 | 0.49 | ||||

| Motivation | 0.82 |

| Path | Estimate | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude→Behavioral Intention | 0.62 | <0.001 | Significant |

| Subjective Norm→Behavioral Intention | 0.5 | <0.001 | Significant |

| Perceived Behavioral Control→Behavioral Intention | 0.58 | <0.001 | Significant |

| Environmental Awareness→Behavioral Intention | 0.1 | 0.12 | Not Significant |

| Moral Obligation→Behavioral Intention | 0.09 | 0.15 | Not Significant |

| Motivation→ Behavioral Intention | 0.44 | <0.001 | Significant |

| Behavioral Intention→Actual Behavior | 0.69 | <0.001 | Significant |

| Latent Variable Pair | Covariance Estimate |

|---|---|

| Attitude↔Subjective Norm | 0.4 |

| Attitude↔Perceived Behavioral Control | 0.45 |

| Attitude↔Environmental Awareness | 0.36 |

| Attitude↔Moral Obligation | 0.39 |

| Attitude↔Motivation | 0.42 |

| Subjective Norm↔Perceived Behavioral Control | 0.35 |

| Subjective Norm↔Environmental Awareness | 0.38 |

| Subjective Norm↔Moral Obligation | 0.36 |

| Subjective Norm↔Motivation | 0.4 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control↔Environmental Awareness | 0.4 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control↔Moral Obligation | 0.38 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control↔Motivation | 0.41 |

| Environmental Awareness↔Moral Obligation | 0.45 |

| Environmental Awareness↔Motivation | 0.46 |

| Moral Obligation↔Motivation | 0.49 |

| Behavioral Intention↔Actual Behavior | 0.66 |

| Hypothesis | Hypothesis Description | Results |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | A positive attitude significantly influences behavioral intentions. | Supported |

| H2 | Subjective norms positively affect behavioral intentions. | Supported |

| H3 | Perceived behavioral control positively impacts behavioral intentions. | Supported |

| H4 | Motivation positively influences behavioral intentions. | Supported |

| H5 | Moral obligation positively affects behavioral intentions. | Not Supported |

| H6 | Environmental awareness positively influences behavioral intentions. | Not Supported |

| H7 | Behavioral intentions significantly influence actual behavior. | Supported |

| Stakeholder | Recommendation | Actionable Example |

|---|---|---|

| Producers | Enhance technical and sustainable practices | Participate in training programs like those offered by Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute (KMFRI) on eco-friendly inputs |

| Consumers | Increase awareness of health and quality benefits | Launch campaigns via local radio to debunk “China fish” misconceptions and highlight nutritional value |

| Policymakers | Provide sustainability incentives | Offer subsidies for certified inputs, as piloted in Homa Bay County |

| NGOs | Facilitate feedback mechanisms | Establish community forums to share consumer preferences with producers |

| Industry | Strengthen supply chain reliability | Invest in cold chain transport to ensure consistent market access |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abwao, M.O.; Bett, H.; Turcekova, N.; Gathungu, E. Behavioral Drivers of Cage Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Producers and Consumers in Kenya’s Lake Victoria Region. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5312. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125312

Abwao MO, Bett H, Turcekova N, Gathungu E. Behavioral Drivers of Cage Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Producers and Consumers in Kenya’s Lake Victoria Region. Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5312. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125312

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbwao, Martin Ochieng, Hillary Bett, Natalia Turcekova, and Edith Gathungu. 2025. "Behavioral Drivers of Cage Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Producers and Consumers in Kenya’s Lake Victoria Region" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5312. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125312

APA StyleAbwao, M. O., Bett, H., Turcekova, N., & Gathungu, E. (2025). Behavioral Drivers of Cage Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Producers and Consumers in Kenya’s Lake Victoria Region. Sustainability, 17(12), 5312. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125312