Tourist Walkability in Traditional Villages: The Role of Built Environment, Shareability, and Personal Attributes

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How does the perception of the immediate built environment affect tourist walkability in traditional villages?

- To what extent does a place’s shareability influence tourist walkability?

- How do personal attributes contribute to variations in tourist walkability?

- What is the relative importance of these factors in influencing tourist walkability?

2. Literature Review

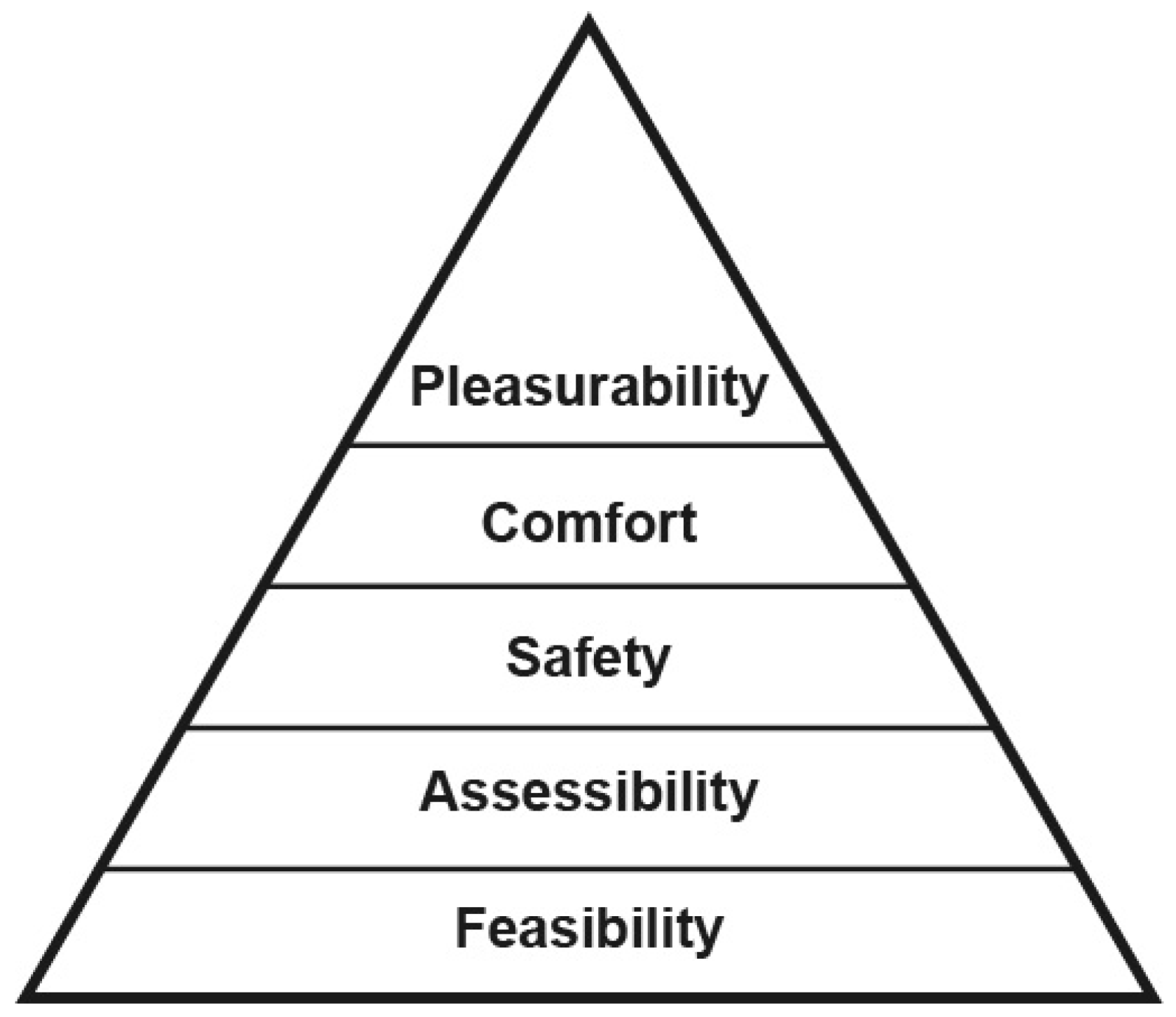

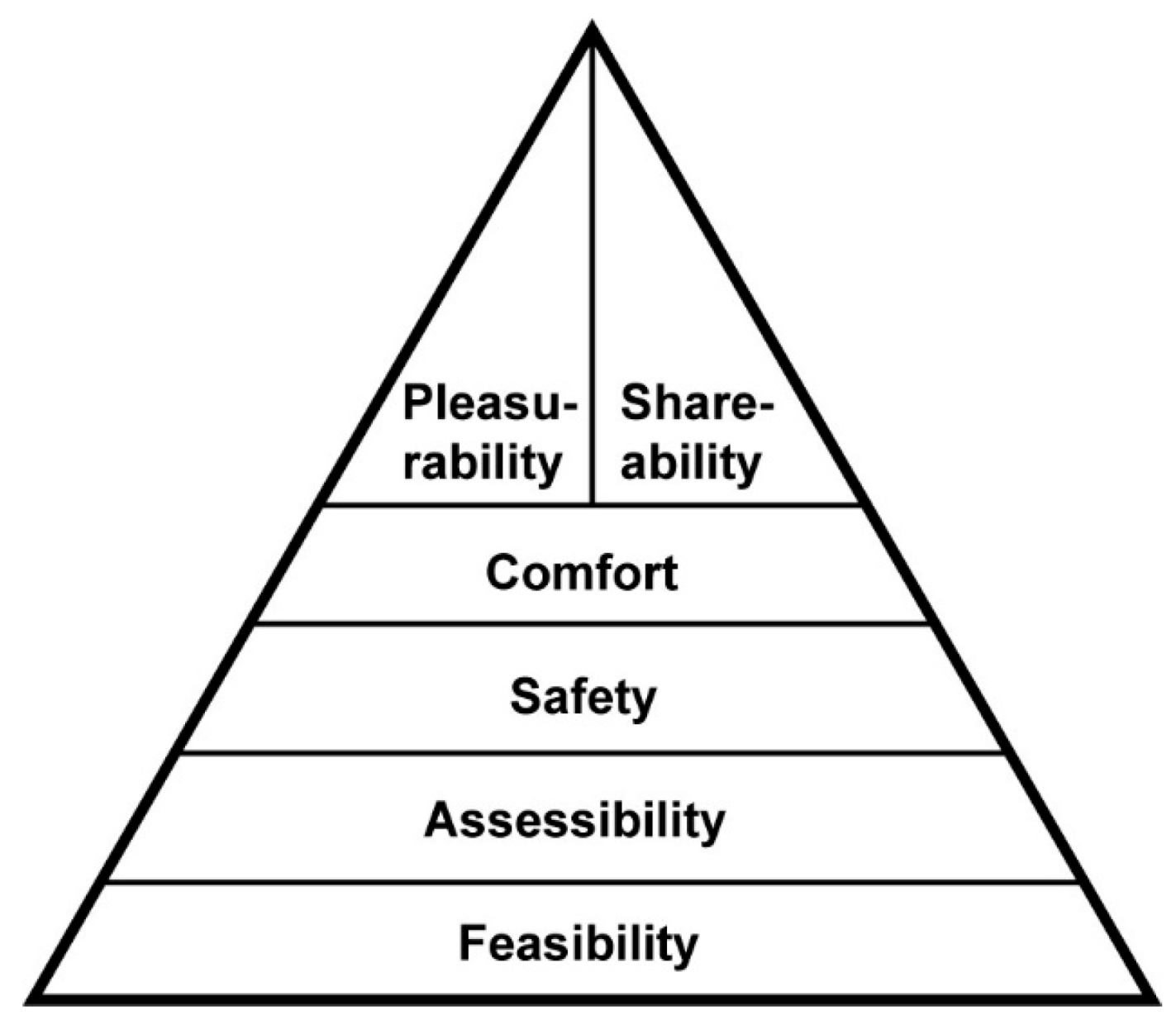

2.1. Theoretical Foundations of Walkability

2.2. Tourist Walkability

2.3. Tourist Walking in Traditional Villages

2.4. Factors Affecting Tourist Walkability

2.4.1. Built Environment Factors

2.4.2. Personal Attributes

2.4.3. Social Media Sharing

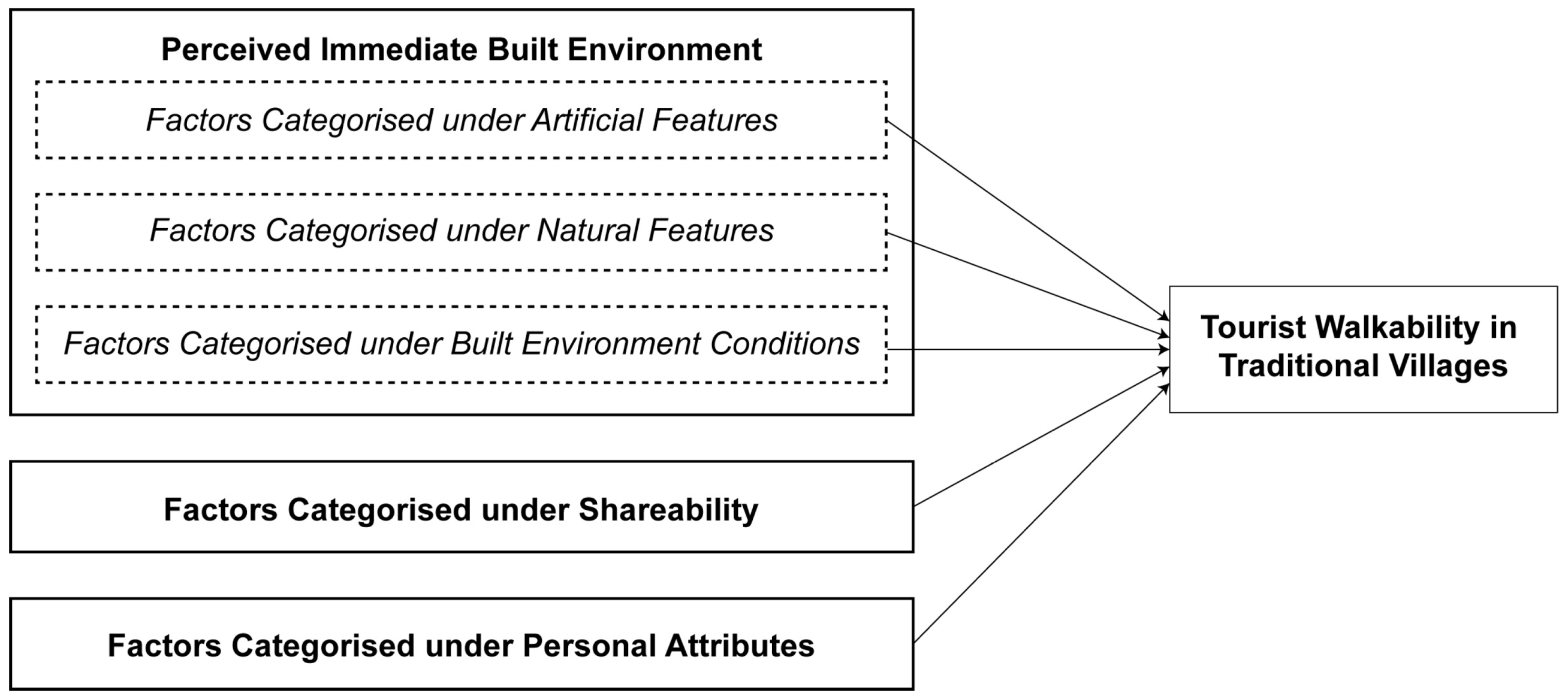

2.5. Conceptual Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Identification of Factors Affecting Tourist Walkability in Traditional Villages

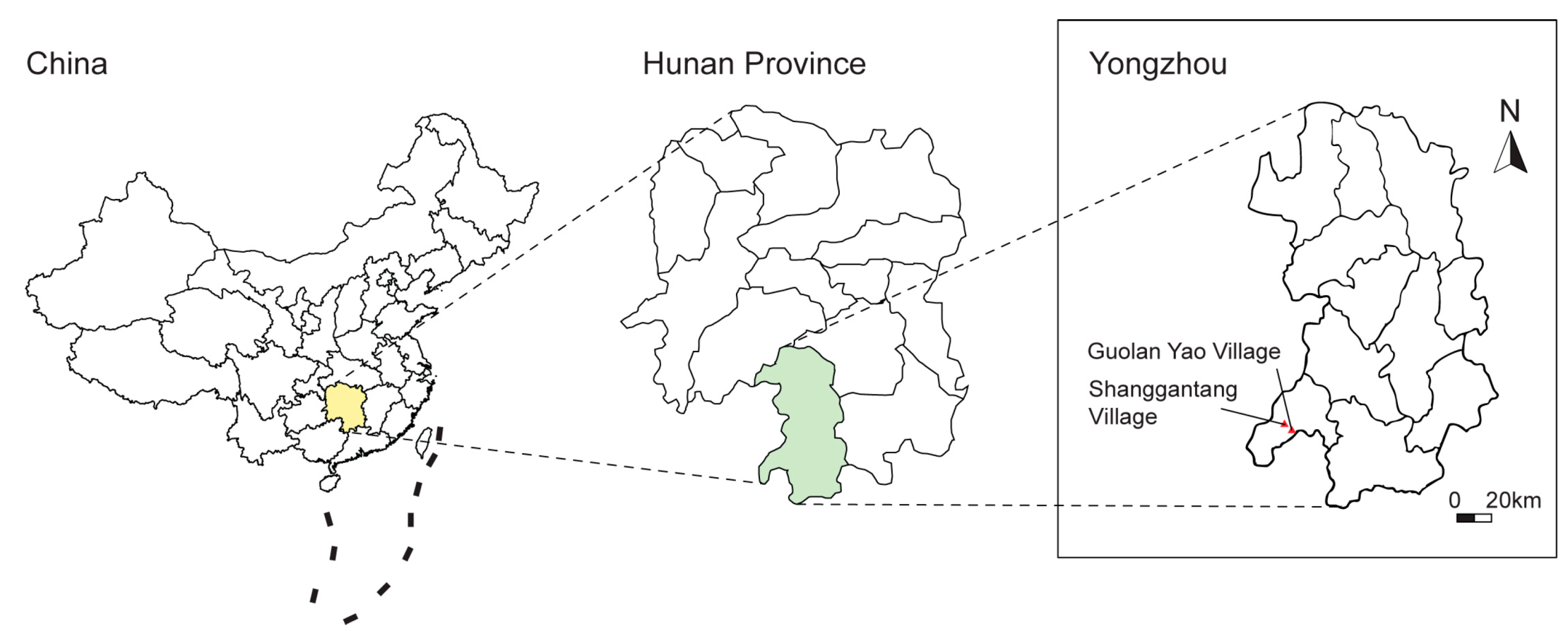

3.2. Site and Survey Location Selection

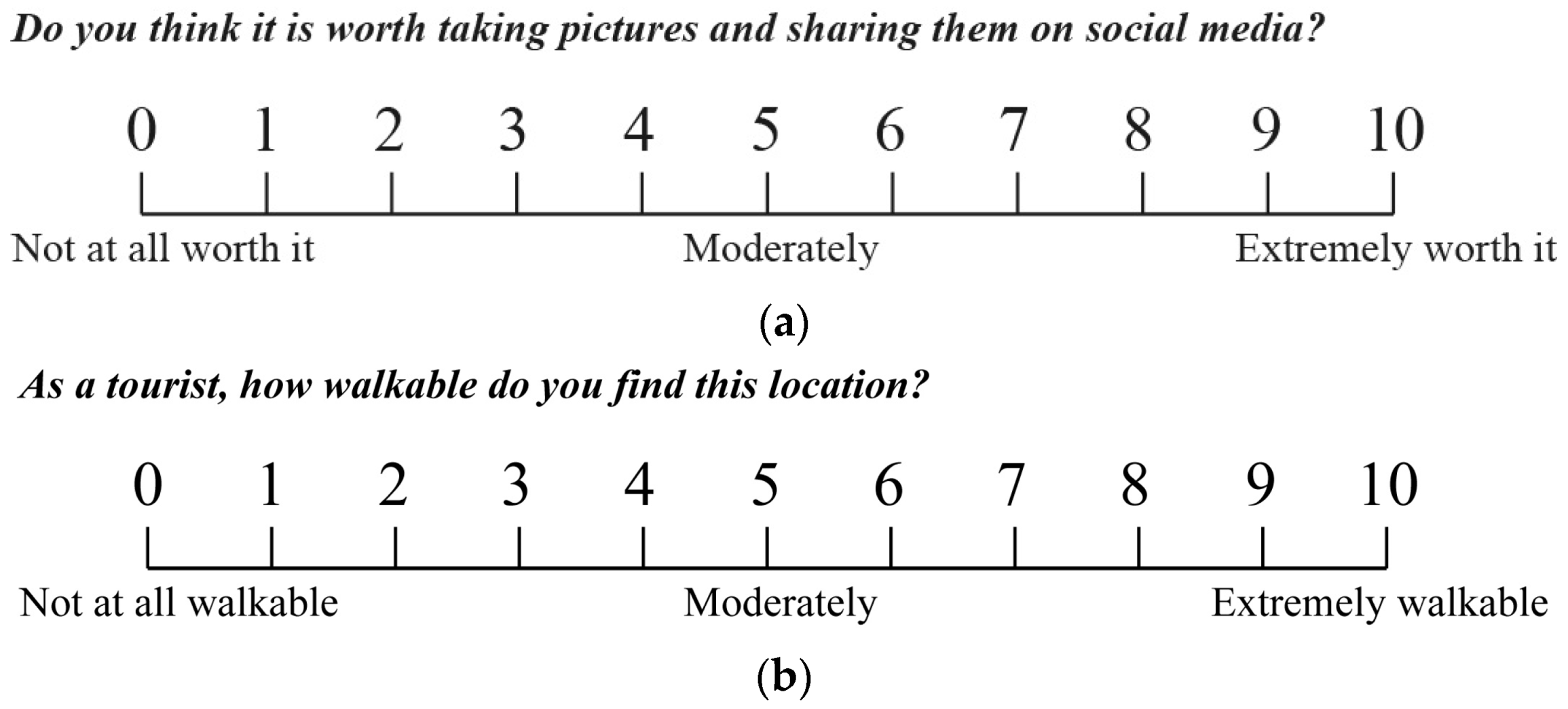

3.3. Questionnaire Survey

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

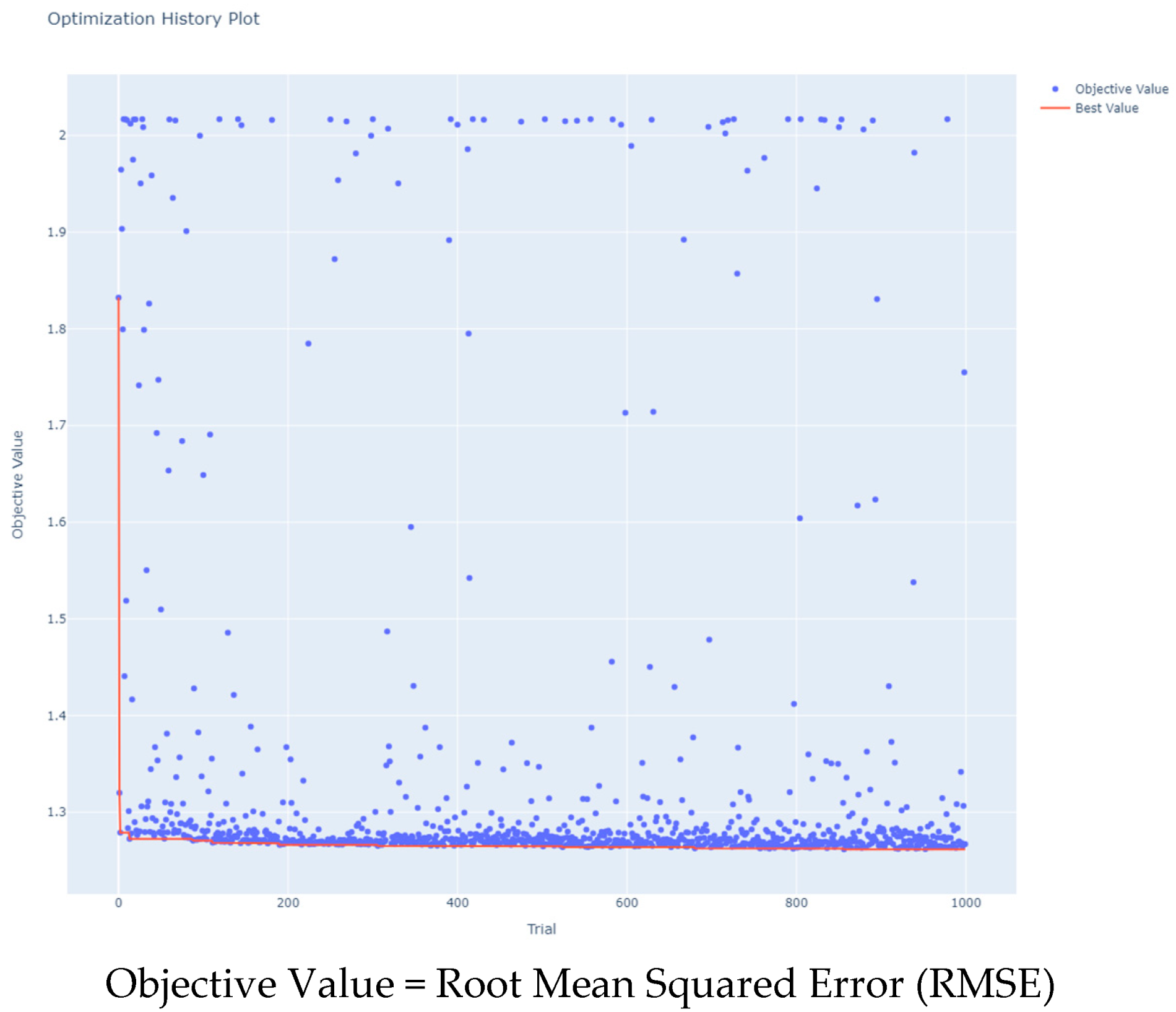

4.1. Tourist Walkability Prediction Model Development

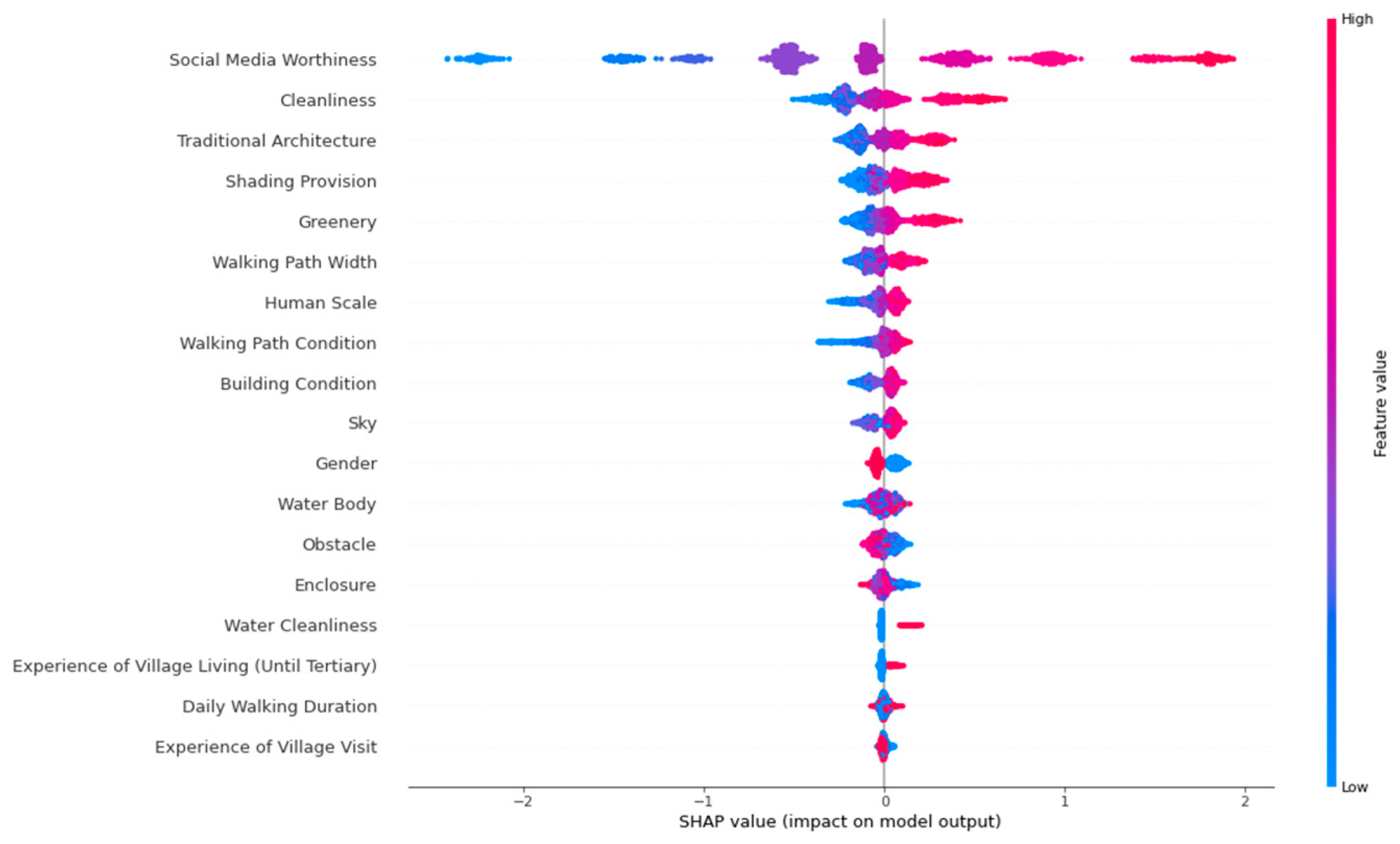

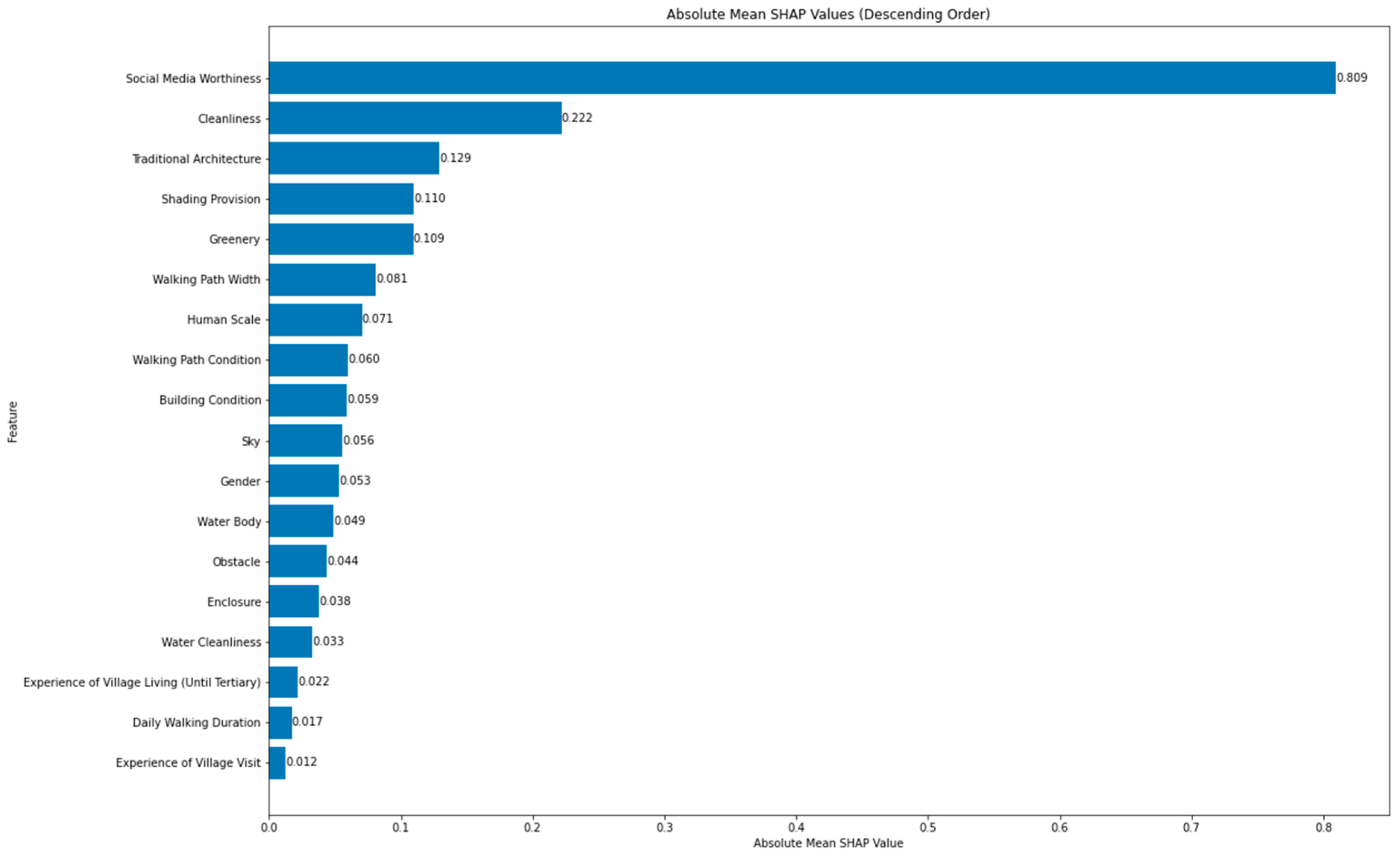

4.2. Importance Weightings of Factors Affecting Tourist Walkability

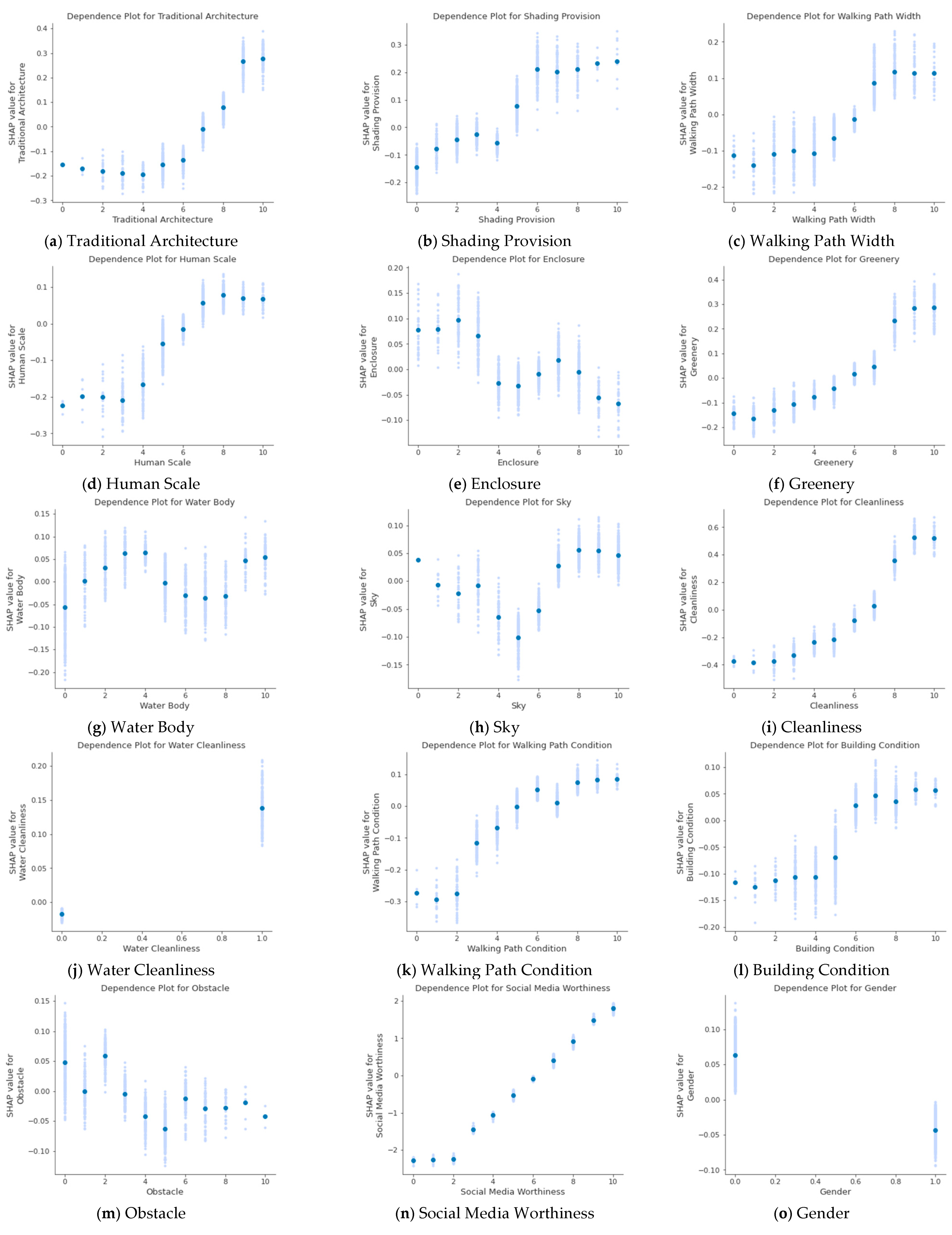

4.3. Effects of Individual Factors Affecting Tourist Walkability

4.3.1. Perceived Immediate Built Environment

4.3.2. Shareability

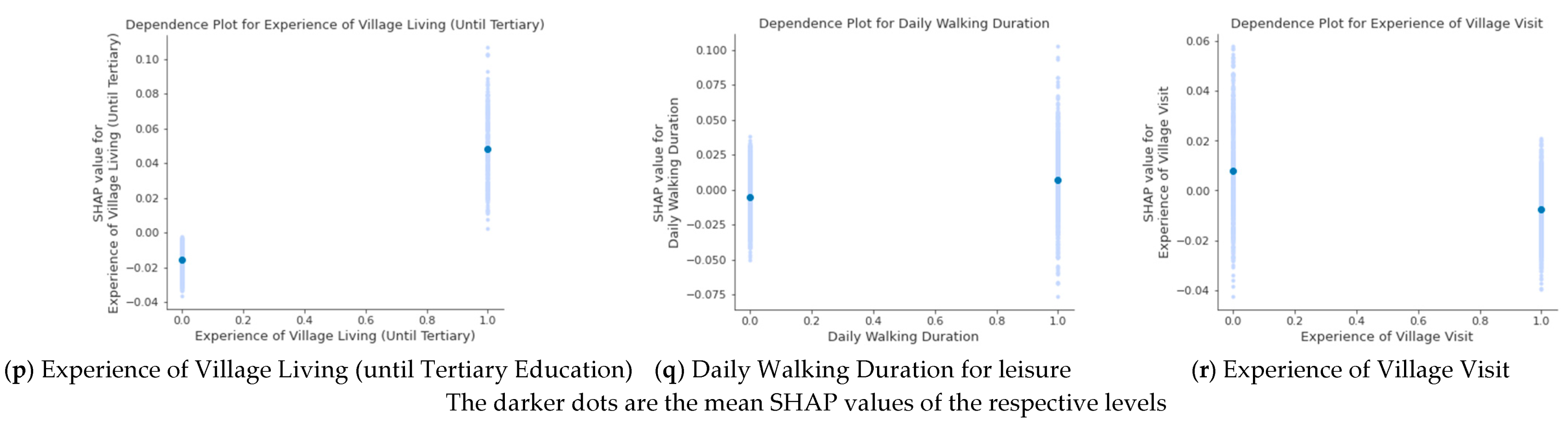

4.3.3. Personal Attributes

5. Discussion

5.1. Walking Needs Underpinning Tourist Walkability

5.2. Immediate Built Environment and Tourist Walkability in Traditional Villages

5.3. Policy and Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Studies

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Edwards, D.; Griffin, T. Understanding Tourists’ Spatial Behaviour: GPS Tracking as an Aid to Sustainable Destination Management. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 580–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, G.; Agarwal, S.; Bull, P. Tourism Consumption and Tourist Behaviour: A British Perspective. Tour. Geogr. 2000, 2, 264–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujang, N.; Muslim, Z. Walkability and Attachment to Tourism Places in the City of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Athens J. Tour. 2014, 2, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Le-Klähn, D.-T.; Ram, Y. Tourism, Public Transport and Sustainable Mobility; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-84541-600-3. [Google Scholar]

- Mansouri, M.; Ujang, N. Tourist’ Expectation and Satisfaction towards Pedestrian Networks in the Historical District of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Asian Geogr. 2016, 33, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amen, M.A.; Afara, A.; Nia, H.A. Exploring the Link between Street Layout Centrality and Walkability for Sustainable Tourism in Historical Urban Areas. Urban Sci. 2023, 7, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solnit, R. Wanderlust: A History of Walking; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, R.; Gomes da Silva, E.J.; Lima e Lima, T.; Osorio, N. Walkability: A Review of Trends. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2023, 16, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, F.; Ribeiro, P.J.G.; Conticelli, E.; Jabbari, M.; Papageorgiou, G.; Tondelli, S.; Ramos, R.A.R. Built Environment Attributes and Their Influence on Walkability. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2022, 16, 660–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafray, E.; Kim, S. A Study of Walkable Spaces with Natural Elements for Urban Regeneration: A Focus on Cases in Seoul, South Korea. Sustainability 2017, 9, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pira, M.L.; Gemma, A.; Gatta, V.; Carrese, S.; Marcucci, E. Walking and Sustainable Tourism: “Streetsadvisor.” A Stated Preference GIS-Based Methodology for Estimating Tourist Walking Satisfaction in Rome. In Sustainable Transport and Tourism Destinations; Zamparini, L., Ed.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Arellana, J.; Saltarín, M.; Larrañaga, A.M.; Alvarez, V.; Henao, C.A. Urban Walkability Considering Pedestrians’ Perceptions of the Built Environment: A 10-Year Review and a Case Study in a Medium-Sized City in Latin America. Transp. Rev. 2020, 40, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Ren, X.; Yin, L.; Sun, Q.; Song, K.; Wang, D. Investigating Tourists’ Willingness to Walk (WTW) to Attractions within Scenic Areas: A Case Study of Tongli Ancient Town, China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dihingia, S.; Gjerde, M.; Vale, B. Walking Tourist: Review of Research to Date. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2022, 148, 04022017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.; Tučková, Z.; Jibril, A.B. The Role of Social Media on Tourists’ Behavior: An Empirical Analysis of Millennials from the Czech Republic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xie, J.; Chen, S.X. Cannot Wait to Share? An Exploration of Tourists’ Sharing Behavior during the ‘Traveling to the Site’ Stage. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 3640–3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, L.; Li, X. How Does Mobile Social Media Sharing Benefit Travel Experiences? J. Travel Res. 2023, 62, 841–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Gong, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, S.; Chen, P. Understanding Why Tourists Who Share Travel Photos Online Give More Positive Tourism Product Evaluation: Evidence From Chinese Tourists. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 838176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, D.; Wen, H. Research on Protection and Utilization Strategies of Cultural Resources in Traditional Villages of Tourism Development. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 236, 01047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickel-Chevalier, S.; Bendesa, I.K.G.; Darma Putra, I.N. The Integrated Touristic Villages: An Indonesian Model of Sustainable Tourism? Tour. Geogr. 2021, 23, 623–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovicic, D. Cultural Tourism in the Context of Relations between Mass and Alternative Tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varolgüneş, F.K.; Doğan, E.; Varolgüneş, S. The Role of Traditional Architecture in the Development of Rural Tourism: The Case of Turkey. Int. J. Sci. Study 2017, 5, 237–243. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, K.; Abe, H.; Otsuka, N.; Yasufuku, K.; Takahashi, A. A Comprehensive Evaluation of Walkability in Historical Cities: The Case of Xi’an and Kyoto. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernawadi, Y.; Putra, H.T. Authenticity and Walkability of Iconic Heritage Destination in Bandung Indonesia. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Manag. 2021, 2, 1082–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battista, G.A.; Manaugh, K. Stores and Mores: Toward Socializing Walkability. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 67, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, K.M.S. Liveable City Centre: Livability through The Lens of The Singaporean Experience (Case of Singapore City Center). Eng. Res. J. 2022, 176, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmat, R.R.; Mooney, S.J.; Hurvitz, P.M.; Zhou, C.; Moudon, A.V.; Saelens, B.E. Walkability Measures to Predict the Likelihood of Walking in a Place: A Classification and Regression Tree Analysis. Health Place 2021, 72, 102700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.A.; Curtin, K.D.; Thomson, M.; Kung, J.Y.; Nykiforuk, C.I.J. Contributions and Limitations Walk Score® in the Context of Walkability: A Scoping Review. Environ. Behav. 2023, 55, 468–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.M.; Wang, Z.; Vaartjes, I.; Karssenberg, D.; Ettema, D.; Helbich, M.; Timmermans, E.J.; Frank, L.D.; den Braver, N.R.; Wagtendonk, A.J.; et al. Development of an Objectively Measured Walkability Index for the Netherlands. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L.D.; Sallis, J.F.; Saelens, B.E.; Leary, L.; Cain, K.; Conway, T.L.; Hess, P.M. The Development of a Walkability Index: Application to the Neighborhood Quality of Life Study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2009, 44, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, J.; Mondschein, A.; Neale, C.; Barnes, L.; Boukhechba, M.; Lopez, S. The Urban Built Environment, Walking and Mental Health Outcomes Among Older Adults: A Pilot Study. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 575946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rundle, A.G.; Heymsfield, S.B. Can Walkable Urban Design Play a Role in Reducing the Incidence of Obesity-Related Conditions? JAMA 2016, 315, 2175–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, I.; Choi, M.; Kwak, J.; Ku, D.; Lee, S. A Comprehensive Walkability Evaluation System for Promoting Environmental Benefits. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagata, Y.; Murakami, D.; Wu, Y.; Yang, P.P.-J.; Yoshida, T.; Binder, R. Big-Data Analysis for Carbon Emission Reduction from Cars: Towards Walkable Green Smart Community. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 4292–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyden, K.M. Social Capital and the Built Environment: The Importance of Walkable Neighborhoods. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1546–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K. The Relationship between Walkability and QOL Outcomes in Residential Evaluation. Cities 2022, 131, 104008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volker, J.M.B.; Handy, S. Economic Impacts on Local Businesses of Investments in Bicycle and Pedestrian Infrastructure: A Review of the Evidence. Transp. Rev. 2021, 41, 401–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litman, T. Economic Value of Walkability; Victoria Transport Policy Institute: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Kamphuis, C.B.M.; Helbich, M.; Ettema, D. What Is ‘Neighborhood Walkability’? How the Built Environment Differently Correlates with Walking for Different Purposes and with Walking on Weekdays and Weekends. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 88, 102860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigue, L.; El-Geneidy, A.; Manaugh, K. Sociodemographic Matters: Analyzing Interactions of Individuals’ Characteristics with Walkability When Modelling Walking Behavior. J. Transp. Geogr. 2024, 114, 103788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaugh, K.; El-Geneidy, A. Validating Walkability Indices: How Do Different Households Respond to the Walkability of Their Neighborhood? Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2011, 16, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatamzadeh, Y. Do People Desire to Walk More in Commuting to Work? Examining a Conceptual Model Based on the Role of Perceived Walking Distance and Positive Attitudes. Transp. Res. Rec. 2019, 2673, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, F.; Papageorgiou, G.; Conticelli, E.; Jabbari, M.; Ribeiro, P.J.G.; Tondelli, S.; Ramos, R. Evaluating Attitudes and Preferences towards Walking in Two European Cities. Future Transp. 2024, 4, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonzo, M.A. To Walk or Not to Walk? The Hierarchy of Walking Needs. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 808–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozovic, T.; Hinckson, E.; Smith, M. Why Do People Walk? Role of the Built Environment and State of Development of a Social Model of Walkability. Travel Behav. Soc. 2020, 20, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, P.; Stangl, P.; Guinn, J. Why People Walk: Modeling Foundational and Higher Order Needs Based on Latent Structure. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2017, 10, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaee, S.; Aghaabbasi, M.; Mahdiyar, A.; Zainol, R.; Ismail, S. Measurement Quality Appraisal Instrument for Evaluation of Walkability Assessment Tools Based on Walking Needs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Chau, C.K.; Lai, J.H.K. Critical Factors Influencing the Comfort Evaluation for Recreational Walking in Urban Street Environments. Cities 2021, 116, 103286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulla, K. Walkability in Historic Urban Spaces: Testing the Safety and Security in Martyrs’ Square in Tripoli. Int. J. Archit. Res. 2017, 11, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.K.P. Casual Walking in Urban Tourism Destinations through the Lens of Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O–R) and Hierarchy of Walking Needs Theories. Leis. Stud. 2023, 44, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton Clavé, S. Urban Tourism and Walkability. In The Future of Tourism: Innovation and Sustainability; Fayos-Solà, E., Cooper, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 195–211. ISBN 978-3-319-89941-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cafuta, M.R. Framing the Tourist Spatial Identity of a City as a Tourist Product. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2022, 10, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küpers, W.; Wee, D. Tourist Cities as Embodied Places of Learning: Walking in the “Feelds” of Shanghai and Lisbon. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2018, 4, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freytag, T. Visitor Activities and Inner-City Tourist Mobility: The Case of Heidelberg. In Analysing International City Tourism; Mazanec, J.A., Wöber, K.W., Eds.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2010; pp. 213–226. ISBN 978-3-211-09416-7. [Google Scholar]

- Rabbiosi, C.; Meneghello, S. Questioning Walking Tourism from a Phenomenological Perspective: Epistemological and Methodological Innovations. Humanities 2023, 12, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dihingia, S.; Gjerde, M.; Vale, B. The Walking Tourist: How Do the Perceptions of Tourists and Locals Compare? In Proceedings of the Architectural Science and User Experience: How can Design Enhance the Quality of Life, Perth, Australia, 1–2 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gorrini, A.; Bertini, V. Walkability Assessment and Tourism Cities: The Case of Venice. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2018, 4, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, Y.; Hall, C.M. Walkable Places for Visitors: Assessing and Designing for Walkability. In The Routledge International Handbook of Walking; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 311–329. [Google Scholar]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Regalado-Pezúa, O.; Sirkis, G.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Carvache-Franco, W. Market Segmentation in Urban Tourism: A Study in Latin America. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milojković, D.; Milojković, K.; Milojković, H. Management Of Countryside Walking Tourism Through Understanding Users and Their Needs. Sci. Int. J. 2023, 2, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Leng, J. Evaluation of Public Space in Traditional Villages Based on Eye Tracking Technology. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 23, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Liu, P.; Huang, L.; Feng, S.; Li, Y. Features of Architectural Landscape Fragmentation in Traditional Villages in Western Hunan, China. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Tian, Y.; Gao, B.; Wang, S.; Qi, Y.; Zou, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, R. A Study on Identifying the Spatial Characteristic Factors of Traditional Streets Based on Visitor Perception: Yuanjia Village, Shaanxi Province. Buildings 2024, 14, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Beza, B.B.; Liu, C.; Wu, B.; Qiu, N. Differences in Perspectives Between Experts and Residents on Living Heritage: A Study of Traditional Chinese Villages in the Luzhong Region. Buildings 2024, 14, 4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Xiao, D.; Li, J.; Xu, Z.; Tao, J. Research on Traditional Village Spatial Differentiation from the Perspective of Cultural Routes: A Case Study of 338 Villages in the Miao Frontier Corridor. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, H.; An, Y. Spatial Morphology and Geographic Adaptability of Traditional Villages in the Hehuang Region, China. Buildings 2025, 15, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Gu, Y. Revisiting the Spatial Form of Traditional Villages in Chaoshan, China. Open House Int. 2020, 45, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xie, W.; Li, H. The Spatial Evolution Process, Characteristics and Driving Factors of Traditional Villages from the Perspective of the Cultural Ecosystem: A Case Study of Chengkan Village. Habitat Int. 2020, 104, 102250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Cao, Y. Improvement of Traditional Village Protection Infrastructure Management System. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Social Sciences and Economic Development (ICSSED 2020), Xian, China, 6–8 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Lehto, X.; Lehto, M.; Day, J. Can Colored Sidewalk Nudge City Tourists to Walk? An Experimental Study of the Effect of Nudges. Tour. Manag. 2023, 95, 104683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.J.; Kang, D.J.; Lee, M.J. Spatiotemporal Distribution of Urban Walking Tourists by Season Using GPS-Based Smartphone Application. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 1047–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Hall, C.M. Do Smart Apps Encourage Tourists to Walk and Cycle? Comparing Heavy versus Non-Heavy Users of Smart Apps. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 27, 763–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Hall, C.M. Is Tourist Walkability and Well-Being Different? Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abyaneh, A.B.; Allan, A.; Pieters, J.; Davison, G. Developing a GIS-Based Tourist Walkability Index Based on the AURIN Walkability Toolkit—Case Study: Sydney CBD. In Urban Informatics and Future Cities; The Urban Book Series; Springer Nature: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 233–256. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Choi, K.; Lee, J.S. Operationalization of Path Walkability for Sustainable Transportation. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2017, 11, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech, A.; Gutiérrez, A.; Anton Clavé, S. Built Environment and Urban Cruise Tourists’ Mobility. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 81, 102889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dihingia, S.; Gjerde, M.; Vale, B. The Walking Tourist: An Investigation of People’s Perceptions When Walking. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Future of Urban Public Space, Tehran, Iran, 8–10 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Samarasekara, G.N.; Fukahori, K.; Kubota, Y. Environmental Correlates That Provide Walkability Cues for Tourists: An Analysis Based on Walking Decision Narrations. Environ. Behav. 2011, 43, 501–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkić, J.; Perić, D.; Lesjak, M.; Petelin, M. Urban Walking: Perspectives of Locals and Tourists. Geogr. Pannonica 2015, 19, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Sun, G.; Li, Y. Modeling the Perception of Walking Environmental Quality in a Traffic-Free Tourist Destination. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 608–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakar, K.; Harman, S.; Aykol, S. A Research on Walkability Perception of Tourists Visiting Old Town Mardin. In Proceedings of the 4th International Tourism Congress, Eskişehir, Turkey, 16–19 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Das, S.; Bhattacharya, S. Factors Affecting Beach Walkability- Tourists’ Perception Study at Selected Beaches of West Bengal, India. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 35, 100423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharjee, S.K.; Ahmed, T. The Impact of Social Media on Tourists’ Decision-Making Process: An Empirical Study Based on Bangladesh. J. Soc. Sci. Manag. Stud. 2024, 3, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilashi, M.; Ibrahim, O.; Yadegaridehkordi, E.; Samad, S.; Akbari, E.; Alizadeh, A. Travelers Decision Making Using Online Review in Social Network Sites: A Case on TripAdvisor. J. Comput. Sci. 2018, 28, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandafatu, N.K.; Ermilinda, L.; Darkel, Y.B.M. Digital Transformation in Tourism: Exploring the Impact of Technology on Travel Experiences. Int. J. Multidiscip. Approach Sci. Technol. 2024, 1, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Liberato, P.M.; Alén-González, E.; de Azevedo Liberato, D.F.V. Digital Technology in a Smart Tourist Destination: The Case of Porto. J. Urban Technol. 2018, 25, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Qiao, G.; Shao, Z.; Jiang, T.; Wen, C.; Zhong, Y.; Li, Z. Understanding Continuous Sharing Behavior of Online Travel Community Users: A Case of TripAdvisor. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2023, 21, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasution, R.A.; Windasari, N.A.; Mayangsari, L.; Arnita, D. Travellers’ Online Sharing across Different Platforms: What and Why? J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2023, 14, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xiang, Z.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Adapting to the Mobile World: A Model of Smartphone Use. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 48, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M.J.; Johns, R.; Dale, N.F. The Social Media Tourist Gaze: Social Media Photography and Its Disruption at the Zoo. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2019, 21, 391–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Schuett, M.A. Determinants of Sharing Travel Experiences in Social Media. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.; Araujo, B.; Tam, C. Why Do People Share Their Travel Experiences on Social Media? Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widiana, R.; Novani, S. Factors Influencing Tourists’ Travel Experience Sharing on Social Media. Indones. J. Bus. Entrep. (IJBE) 2022, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Bai, B. The Effects of Photo-Sharing Motivation on Tourist Well-Being: The Moderating Role of Online Social Support. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 51, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arica, R.; Cobanoglu, C.; Cakir, O.; Corbaci, A.; Hsu, M.-J.; Della Corte, V. Travel Experience Sharing on Social Media: Effects of the Importance Attached to Content Sharing and What Factors Inhibit and Facilitate It. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 1566–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetinsöz, B.C.; Cakır, O.; Durdu, K.M.; Arıca, R. Examining the Effects of Importance Attached to Content Sharing and Knowledge Sharing Facilitators on Tourists’ Actual Travel Experience Sharing Behaviour. Tour. Int. Interdiscip. J. 2024, 72, 566–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggarawati, S.; Saputra, F.E. If I Don’t Share My Unforgettable Journey, I’ll Lose It! Young Travellers’ Propensity to Share e-WOM on Social Media. Front. Bus. Econ. 2023, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daxböck, J.; Dulbecco, M.L.; Kursite, S.; Nilsen, T.K.; Rus, A.D.; Yu, J.; Egger, J. The Implicit and Explicit Motivations of Tourist Behaviour in Sharing Travel Photographs on Instagram: A Path and Cluster Analysis. In Proceedings of the Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaderi, Z.; Béal, L.; Zaman, M.; Hall, C.M.; Rather, R.A. How Does Sharing Travel Experiences on Social Media Improve Social and Personal Ties? Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 3478–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughairi, H.A.; Bhaskar, P. Share or Not to Share: Motivators and Inhibitors of Travellers’ Experience on Social Media: A Qualitative Approach. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2024, 14, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Khabiri, S.; Pourjafar, M.R.; Izadi, M.S. A Case Study of Walkability and Neighborhood Attachment. Glob. J. Hum.-Soc. Sci. 2020, 20, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohsari, M.J.; Yasunaga, A.; Oka, K.; Nakaya, T.; Nagai, Y.; McCormack, G.R. Place Attachment and Walking Behaviour: Mediation by Perceived Neighbourhood Walkability. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 235, 104767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaabbasi, M.; Moeinaddini, M.; Zaly Shah, M.; Asadi-Shekari, Z. A New Assessment Model to Evaluate the Microscale Sidewalk Design Factors at the Neighbourhood Level. J. Transp. Health 2017, 5, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi-Shekari, Z.; Moeinaddini, M.; Aghaabbasi, M.; Cools, M.; Zaly Shah, M. Exploring Effective Micro-Level Items for Evaluating Inclusive Walking Facilities on Urban Streets (Applied in Johor Bahru, Malaysia). Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 49, 101563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labdaoui, K.; Mazouz, S.; Acidi, A.; Cools, M.; Moeinaddini, M.; Teller, J. Utilizing Thermal Comfort and Walking Facilities to Propose a Comfort Walkability Index (CWI) at the Neighbourhood Level. Build. Environ. 2021, 193, 107627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Handy, S. Measuring the Unmeasurable: Urban Design Qualities Related to Walkability. J. Urban Des. 2009, 14, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereitschaft, B. Equity in Microscale Urban Design and Walkability: A Photographic Survey of Six Pittsburgh Streetscapes. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L. Street Level Urban Design Qualities for Walkability: Combining 2D and 3D GIS Measures. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2017, 64, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarawneh, D. Sidewalk Challenges in Amman, Jordan, and the Urge for Context-Specific Walkability Measurement and Evaluation Tools. In Sustainable Development and Social Responsibility, Proceedings of the 2nd American University in the Emirates International Research Conference, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 13–15 November 2018; Al-Masri, A.N., Al-Assaf, Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 2, pp. 203–218. [Google Scholar]

- Aghaabbasi, M.; Moeinaddini, M.; Zaly Shah, M.; Asadi-Shekari, Z.; Arjomand Kermani, M. Evaluating the Capability of Walkability Audit Tools for Assessing Sidewalks. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 37, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, K. Assessing Sidewalk and Corridor Walkability in Developing Countries. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, B.W.; Guhathakurta, S.; Botchwey, N. Development and Validation of Automated Microscale Walkability Audit Method. Health Place 2022, 73, 102733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniruzzaman, M.; Páez, A. A Model-Based Approach to Select Case Sites for Walkability Audits. Health Place 2012, 18, 1323–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz-Wood, M.; Kestens, Y. Does the Effect of Walkable Built Environments Vary by Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status? Prev. Med. 2015, 81, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebbins, R. Exploratory Research in the Social Sciences; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-1-4129-8424-9. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Leung, S.-O. Can Likert Scales Be Treated as Interval Scales?—A Simulation Study. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2017, 43, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.; Jiang, W.-G.; Qin, Q.-H.; Liu, Y.-C.; Li, M.-L. Optimized XGBoost Model with Small Dataset for Predicting Relative Density of Ti-6Al-4V Parts Manufactured by Selective Laser Melting. Materials 2022, 15, 5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirata, K.; Nakaura, T.; Nakagawa, M.; Kidoh, M.; Oda, S.; Utsunomiya, D.; Yamashita, Y. Machine Learning to Predict the Rapid Growth of Small Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2020, 44, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregoriades, A.; Pampaka, M.; Herodotou, H.; Christodoulou, E. Explaining Tourist Revisit Intention Using Natural Language Processing and Classification Techniques. J. Big Data 2023, 10, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Peng, J. Customer Purchase Forecasting for Online Tourism: A Data-Driven Method with Multiplex Behavior Data. Tour. Manag. 2021, 87, 104357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, B.; Xiao, L. Non-Linear Associations between Built Environment and Active Travel for Working and Shopping: An Extreme Gradient Boosting Approach. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 92, 103034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the Advances in neural information processing systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, J.; Choi, M.; Kwak, J.; Van Fan, Y.; Lee, S. Revealing Relationships between Levels of Air Quality and Walkability Using Explainable Artificial Intelligence Techniques. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, D.; Park, J. A Machine Learning and Computer Vision Study of the Environmental Characteristics of Streetscapes That Affect Pedestrian Satisfaction. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, P.; Murphy, M.; Mutrie, N. The Health Benefits of Walking. In Walking (Transport and Sustainability); Emerald Publishing Limited: Leed, UK, 2017; Volume 9, pp. 61–79. ISBN 978-1-78714-628-0. [Google Scholar]

- Rissel, C.; Curac, N.; Greenaway, M.; Bauman, A. Physical Activity Associated with Public Transport Use--a Review and Modelling of Potential Benefits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 2454–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Ho, T.; Benesty, M.; Tang, Y. Understand Your Dataset with XGBoost. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/xgboost/vignettes/discoverYourData.html#numeric-v.s.-categorical-variables (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. Optuna: A Next-Generation Hyperparameter Optimization Framework. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 2623–2631. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S. SHAP Documentation. Available online: https://shap.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Tufft, C.; Constantin, M.; Pacca, M.; Mann, R.; Gladstone, I.; de Vries, J. The State of Tourism and Hospitality 2024; McKinsey & Company: Sydney, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, R.; Li, Y. Exploring the Impact of Built Environment Attributes on Social Followings Using Social Media Data and Deep Learning. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; Ye, Y.; Hou, J.; Long, Y. Revealing the Spatial Preferences Embedded in Online Activities: A Case Study of Chengdu, China. In Urban Informatics and Future Cities; Geertman, S.C.M., Pettit, C., Goodspeed, R., Staffans, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 173–188. ISBN 9783030760588/9783030760595. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Yang, R. The Influence of Aesthetic Design of Consumption Space on Content-Posting Intention on Social Media: The Moderating Role of Aesthetic Perceptual Ability. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Conference on Management Science and Engineering Management, Toledo, Spain, 1–4 August 2021; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bellentani, F.; Arkhipova, D. The Built Environment in Social Media: Towards a Biosemiotic Approach. Biosemiotics 2022, 15, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, I.D.G.A.D.; Adhika, I.M.; Yana, A.A.G.A. Reviving Cultural Tourism in Kendran Bali Indonesia: Maintaining Traditional Architecture and Developing Community-Based Tourism. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2021, 9, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijulie, I.; Lequeux-Dincă, A.-I.; Preda, M.; Mareci, A.; Matei, E.; Cuculici, R.; Taloș, A.-M. Certeze Village: The Dilemma of Traditional vs. Post-Modern Architecture in Țara Oașului, Romania. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Li, Z.; Sun, X. Relevance between Tourist Behavior and the Spatial Environment in Huizhou Traditional Villages—A Case Study of Pingshan Village, Yi County, China. Sustainability 2023, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Devesa, M.; Laguna, M.; Palacios, A. The Role of Motivation in Visitor Satisfaction: Empirical Evidence in Rural Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabanci, O. Historic Architecture in Tourism Consumption. Tour. Crit. Pract. Theory 2022, 3, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fancello, G.; Congiu, T.; Tsoukiàs, A. Mapping Walkability. A Subjective Value Theory Approach. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2020, 72, 100923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, L.A.; Arellana, J.; Castro, W.F. Desirable Streets for Pedestrians: Using a Street-Level Index to Assess Walkability. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2022, 111, 103462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yabuki, N.; Fukuda, T. Measuring Visual Walkability Perception Using Panoramic Street View Images, Virtual Reality, and Deep Learning. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 86, 104140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Chen, J.; Duan, J.; Liu, B. Evaluation of Vernacular Landscape Attraction for Traditional Village Tourism: A Case Study of Yongfeng Village in Lanzhou. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 292, 03058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Delene, L.M.; Bunda, M.A.; Kim, C. Methods of Measuring Health-Care Service Quality. J. Bus. Res. 2000, 48, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Factor | Description | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Immediate Built Environment | Artificial Features | Walking Path Width | Perceived width of walking path | * [105,106,107] |

| Traditional Architecture | Perceived amount of traditional architecture | [3,51,78] | ||

| Shading Provision | Perceived amount of shading provision | [79] | ||

| Human Scale | Perceived degree of human scale | * [108] | ||

| Enclosure | Perceived degree of enclosure | * [108,109] | ||

| Natural Features | Greenery | Perceived amount of greenery | [11,73] | |

| Water Body | Perceived amount of water bodies | * [10] | ||

| Sky | Perceived amount of sky | * [110] | ||

| Built Environment Conditions | Odour | Perceived odour | * [111] | |

| Cleanliness | Perceived degree of cleanliness | [11,81] | ||

| Obstacle | Perceived amount of obstacles along walking path | [79,81] | ||

| Water Cleanliness | Perceived degree of water cleanliness (when water body exists) | Proposed in this study | ||

| Walking Path Condition | Perceived condition (well-maintained or not) of walking path | * [112,113] | ||

| Building Condition | Perceived condition (well-maintained or not) of buildings | * [114,115] | ||

| Shareability | Social Media Worthiness | Perceived degree of worthiness to take pictures and share on social media | Proposed in this study | |

| Personal Attributes | Demographic | Age | Age of participants | [13] |

| Characteristics | Gender | Gender of participants | [13,83] | |

| Employment Status | Employment status of participants | * [116] | ||

| Habits and Experiences | Daily Walking Duration for Leisure | Participants’ daily strolling duration | Proposed in this study | |

| Walking Preference when Travelling | Participants’ preference for walking while travelling | [74] | ||

| Experience of Village Living | Participants’ experience of living in traditional villages | Proposed in this study | ||

| Experience of Village Visit | Participants’ experience of visiting traditional villages | Proposed in this study |

| Variable | Counts | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | M | 58 (57.4%) |

| F | 43 (42.6%) | |

| Age | Below 18 | 10 (9.9%) |

| 18–24 | 82 (81.2%) | |

| 25–34 | 3 (3.0%) | |

| 35–44 | 3 (3.0%) | |

| 45–54 | 1 (1.0%) | |

| 55–64 | 2 (2.0%) | |

| Employment Status | Student | 92 (91.1%) |

| Employed | 7 (6.9%) | |

| Unemployed | 0 (0%) | |

| Retired | 2 (2.0%) | |

| Monthly Expenses (RMB) | 1000 or below | 6 (5.9%) |

| 1001–1500 | 61 (60.4%) | |

| 1501–2000 | 27 (26.7%) | |

| 2001–2500 | 7 (6.9%) | |

| Daily Walking Duration for Leisure (mins) | 0 | 7 (6.9%) |

| 1–15 | 18 (17.8%) | |

| 16–30 | 37 (36.6%) | |

| 31–45 | 20 (19.8%) | |

| 46–60 | 7 (6.9%) | |

| Above 60 | 12 (11.9%) | |

| Residence in Traditional Villages | Never | 15 (14.9%) |

| Until Primary Education | 25 (24.8%) | |

| Until Secondary Education | 22 (21.8%) | |

| Until Tertiary Education | 21 (20.8%) | |

| Only During Vacations | 18 (17.8%) | |

| Visited other Villages Before | Yes | 66 (65.3%) |

| No | 35 (34.7%) | |

| Prefer Walking when Travelling | Yes | 82 (81.2%) |

| No | 19 (18.8%) |

| Category | Aggregated Importance Weighting | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived built environment | 1.061 | Artificial Features | 0.429 |

| Natural Features | 0.214 | ||

| Built Environment Conditions | 0.418 | ||

| Shareability | 0.809 | ||

| Personal attributes | 0.105 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leung, T.M.; Miao, S.; Lin, M.; Hou, H.; Sun, M. Tourist Walkability in Traditional Villages: The Role of Built Environment, Shareability, and Personal Attributes. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5311. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125311

Leung TM, Miao S, Lin M, Hou H, Sun M. Tourist Walkability in Traditional Villages: The Role of Built Environment, Shareability, and Personal Attributes. Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5311. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125311

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeung, Tze Ming, Siyu Miao, Minqi Lin, Huiying (Cynthia) Hou, and Ming Sun. 2025. "Tourist Walkability in Traditional Villages: The Role of Built Environment, Shareability, and Personal Attributes" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5311. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125311

APA StyleLeung, T. M., Miao, S., Lin, M., Hou, H., & Sun, M. (2025). Tourist Walkability in Traditional Villages: The Role of Built Environment, Shareability, and Personal Attributes. Sustainability, 17(12), 5311. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125311

_Li.png)

_Hou.png)