3.2. Tailored ESG Framework for Saudi Arabia

To reflect Saudi Arabia’s distinct development path and sustainability priorities, we construct a country-specific ESG index that diverges from standard global templates. Given the country’s reliance on fossil fuels and its ongoing institutional reforms, a localized ESG framework allows for a more meaningful assessment of environmental, social, and governance contributions to economic growth.

The environmental dimension of the ESG index is composed of greenhouse gas emissions, weighted by carbon dioxide emissions (50%), methane emissions (25%), and nitrous oxide emissions (25%), using data from the World Bank [

38] and the IEA [

39]. This structure reflects Saudi Arabia’s carbon intensity and transition strategies under Vision 2030, which was officially launched in April 2016. Under the Saudi Green Initiative, the Kingdom pledged to reduce 278 million tons of CO

2 emissions annually by 2030, with a broader goal of net-zero emissions by 2060 [

40]. Policies such as liquid fuel phase-out, expansion of renewables to 50% of electricity generation, and carbon capture investments underpin these targets [

41,

42]. According to World Bank data, CO

2 emissions per capita fell from 20.51 metric tons in 2016 to 18.73 in 2023—a 4.9% decline, which, though not a direct proxy for total national emissions, reflects meaningful progress. Supporting this, empirical evidence by [

31] shows that renewable energy reforms introduced between 2019 and 2020 have significantly altered the relationships among FDI, renewable energy use, and GDP, demonstrating the structural impact of recent environmental policy efforts.

The social dimension includes indicators such as the unemployment rate, female labor force participation, tertiary education gender parity, and life expectancy. These aligned with Saudi Arabia’s Human Capability Development Program under Vision 2030, which aims to reduce structural labor market barriers and expand access to education. Studies by [

28,

29] reinforce the value of these tailored metrics, highlighting their relevance in capturing Saudi-specific labor dynamics and social inclusion reforms.

The governance dimension includes regulatory quality and government effectiveness, which are central to the National Transformation Program. These indicators reflect public sector transparency, efficiency, and institutional reform. Refs. [

24,

27] demonstrate that strong governance structures in the MENA and GCC regions directly influence the success of sustainability and diversification policies, making this dimension a crucial element of the ESG framework.

The ESG index, constructed using normalized values and weighted through principal component analysis (PCA), captures the most significant variance across indicators while remaining anchored in Saudi Arabia’s reform agenda.

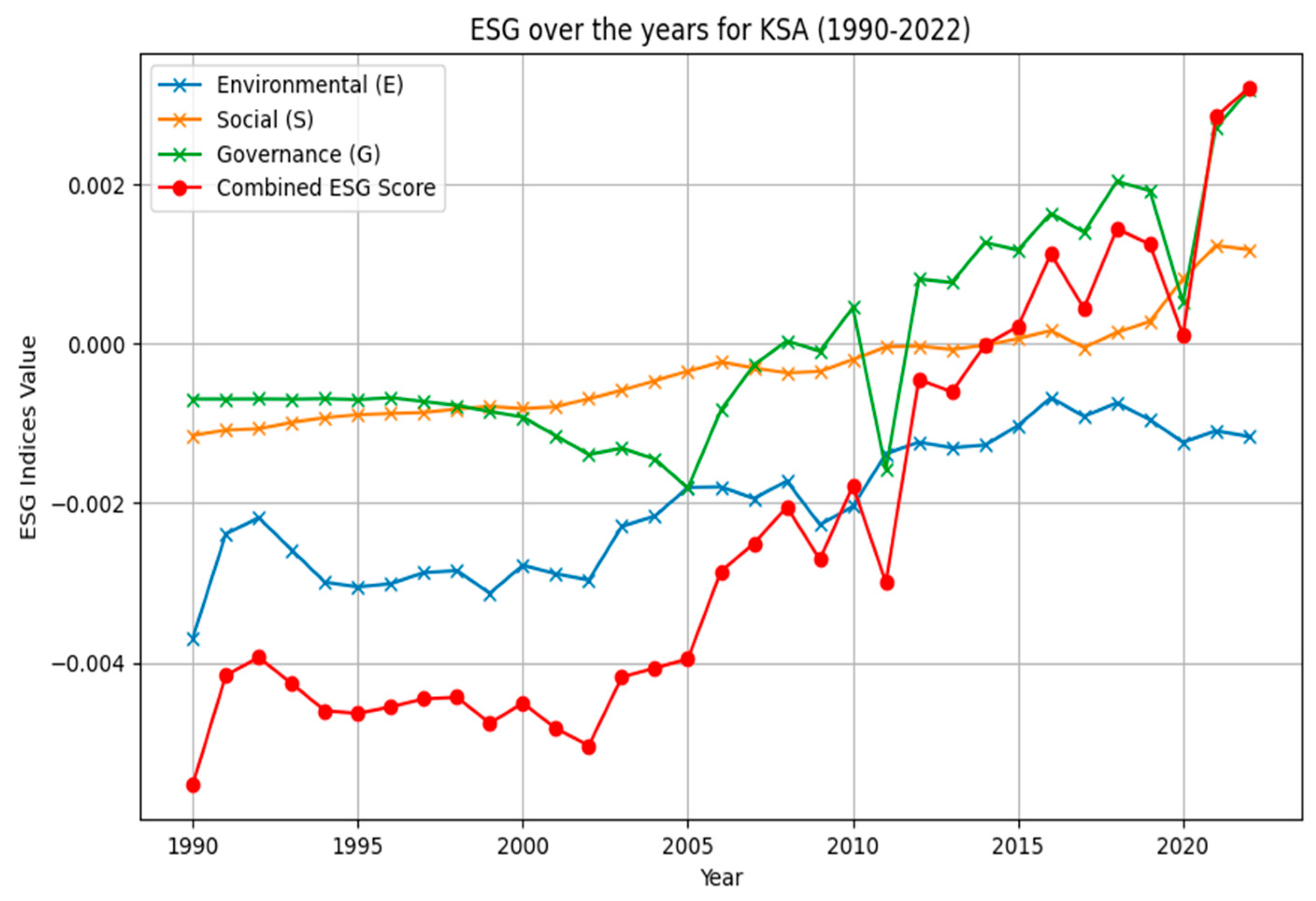

This ESG framework also underpins a steady improvement trend. From 1990 to 2022, Saudi Arabia’s ESG performance has demonstrated consistent progress. The composite ESG index began to rise gradually after 2000, with a notable and sustained increase following the launch of Vision 2030 in 2016. The environmental sub-index, after a volatile performance in the 1990s, began to improve in the mid-2000s, gaining momentum with the introduction of regulatory reforms and renewable energy investments. Social indicators showed steady improvement, particularly after 2017, following institutional changes that enhanced women’s labor market access and improved education alignment. Governance scores experienced the most pronounced gains, especially after 2005, reflecting institutional modernization, anti-corruption enforcement, and digital governance.

This upward ESG trajectory, particularly after 2015, reflects coordinated national strategies such as the Saudi Green Initiative and the National Transformation Program. These institutional and policy shifts provide a strong foundation for examining whether ESG performance contributes to economic growth, a relationship that we empirically test in the subsequent analysis.

The ESG performance trends in Saudi Arabia (1990–2022) are presented in

Figure 2.

Within the ESG components, distinct patterns are observed. The Environmental Index (ENV) exhibited volatility throughout the 1990s, reflecting tensions between fossil-fuel-based growth and environmental externalities. A notable mid-1990s dip in ENV likely mirrors the absence of strong environmental safeguards during rapid industrialization. From the mid-2000s onward, the ENV index began to improve, with substantial gains after 2015. This shift coincides with a series of environmental policy reforms, including intensified emissions monitoring, stricter regulatory enforcement, rising investments in solar and wind infrastructure, and Saudi Arabia’s alignment with international climate goals.

The Social Index (SOC) trended upward more consistently, especially after 2010, indicating gradual but meaningful progress in human capital development and labor force inclusivity. Reforms in employment regulation and the expansion of technical and tertiary education contributed to greater gender equity and youth participation in the workforce.

A pivotal shift occurred post-2017, with major institutional changes (e.g., removing barriers to women’s labor market participation) accelerating social progress. Strategic investments in education and workforce development also helped to reduce skill mismatches and better align the labor supply with the country’s economic diversification agenda. These improvements correspond with the broader social transformation goals of Vision 2030.

Governance indicators show the most pronounced gains among the ESG components, with improvements becoming especially visible after 2005. This trend reflects advancements in transparency, administrative efficiency, and institutional oversight. The establishment of dedicated anti-corruption agencies, stronger regulatory enforcement, and the deployment of digital government systems have collectively strengthened public sector accountability. Additionally, rising political stability and improved policy continuity in the past decade have contributed to a more predictable investment environment. These institutional improvements are likely enhancing the economy’s absorptive capacity and long-term planning.

Since 2015, improvements across the environmental, social, and governance dimensions have become more integrated and mutually reinforcing. The post-2020 surge in the overall ESG index may reflect the cumulative impact of coordinated national strategies (e.g., the National Transformation Program and the Saudi Green Initiative) and expanded public–private collaboration in infrastructure, clean energy, and institutional reform. This upward ESG trajectory strengthens the basis for the empirical analysis, suggesting that recent sustainability reforms could have tangible effects on Saudi Arabia’s economic growth.

Building on this contextual foundation, we now specify the econometric models used to examine the relationship between ESG performance and GDP growth. To isolate ESG effects, we include three key macroeconomic control variables: oil rents (% of GDP), trade openness (total trade as a share of GDP), and gross fixed capital formation (% of GDP). These controls capture Saudi Arabia’s reliance on natural resources, its engagement with international markets, and its level of domestic investment. All data are sourced from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators.

Table 1 summarizes the full set of variables used in the analysis, along with definitions, data sources, and the supporting literature.

We estimate three econometric models to assess the relationship between ESG indicators and economic growth. The first model applies ordinary least squares (OLS) using disaggregated ESG indices—environmental, social, and governance—as independent variables:

To test the joint impact of ESG dimensions, the second model replaces the individual ESG indicators with a composite ESG score. This specification helps evaluate whether integrated ESG performance has a stronger or more consistent relationship with GDP growth:

Finally, to capture both short- and long-term dynamics, the third model applies an autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) approach. This model is particularly useful for assessing equilibrium relationships over time and accounting for the temporal structure of the data:

We tested for stationarity using ADF tests, cointegration via ARDL bounds testing, multicollinearity through VIF, autocorrelation via Breusch–Godfrey LM tests, and heteroscedasticity using Breusch–Pagan. These diagnostics confirm the reliability of the model estimates.

Finally, this methodological framework supports policy evaluation by linking ESG reforms—such as emissions reduction and gender inclusion—to measurable macroeconomic outcomes. In the context of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, the models are designed to provide empirical evidence on whether sustainability-oriented reforms contribute to long-term economic transformation in a resource-dependent economy.