The Impact of ESG Management Activities on the Organizational Performance of Manufacturing Companies in South Korea: The Moderating Effect of Job Position

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. ESG Management

2.2. Organizational Trust

2.3. Organizational Commitment

2.4. Organizational Performance

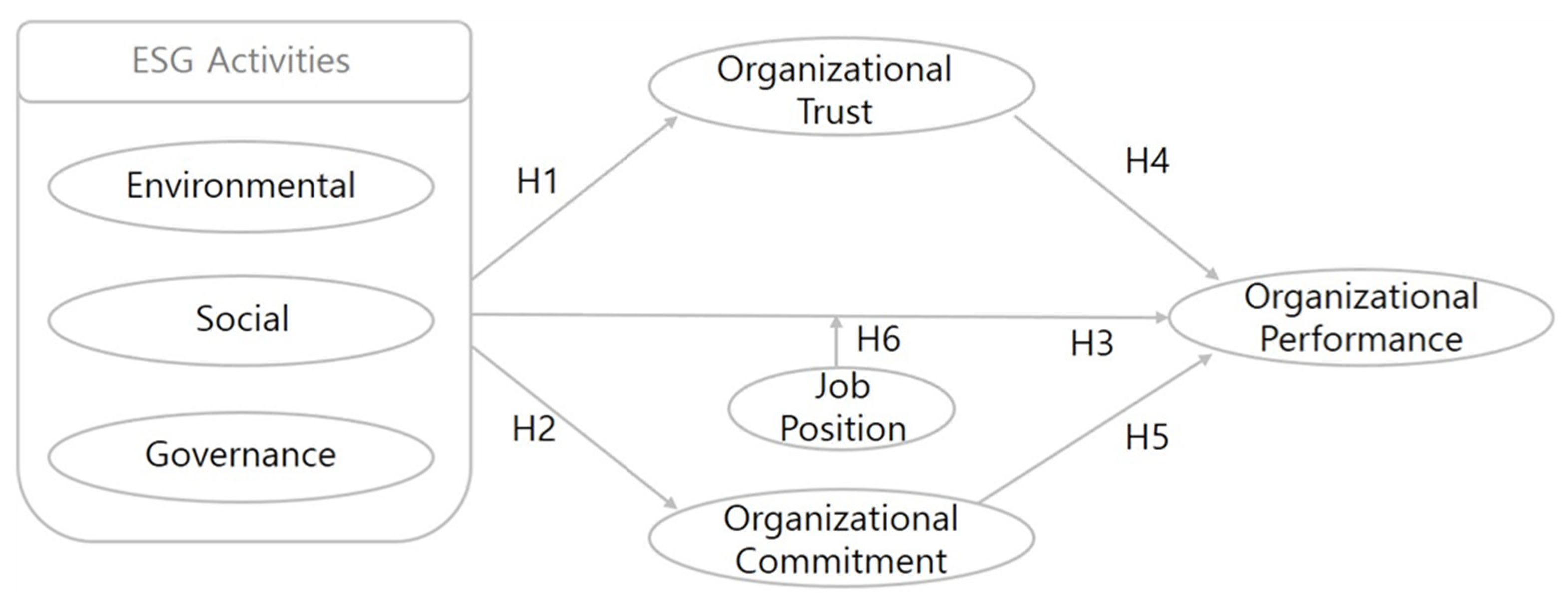

3. Research Model and Hypothesis

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Hypothesis

3.2.1. ESG Management Activities and Organizational Trust

3.2.2. ESG Management Activities and Organizational Commitment

3.2.3. ESG Management Activities and Organizational Performance

3.2.4. Organizational Trust and Organizational Performance

3.2.5. Organizational Commitment and Organizational Performance

3.2.6. Moderating Effect of Job Position Difference

3.3. Operational Definition of Variables

3.4. Data Collection and Research Methods

4. Empirical Analysis Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

4.2. Reliability and Validity Testing

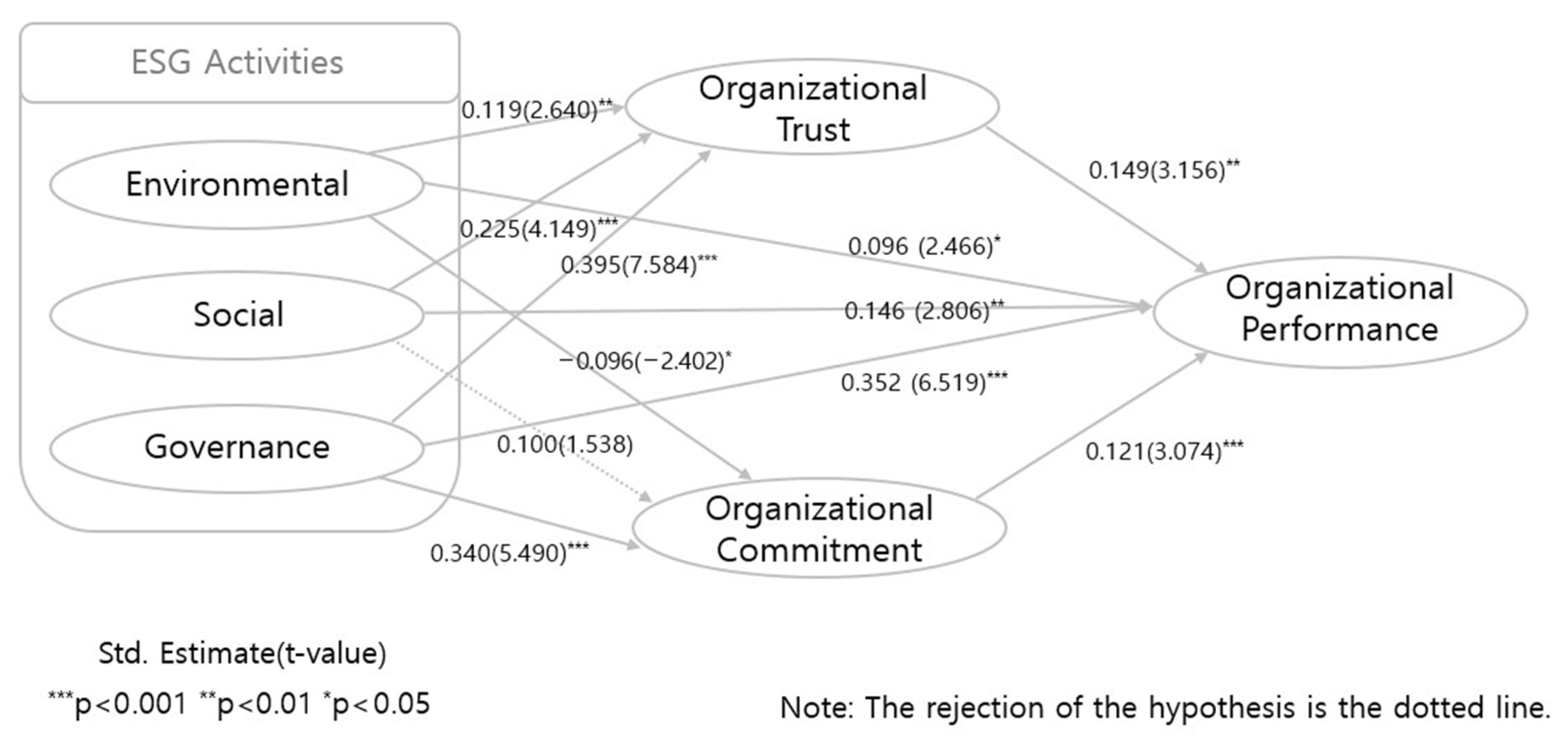

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Conclusions and Future Research

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Measurement Items |

| Environmental from Park et al. [16]. |

| E1 Our company complies with international environmental agreements and domestic regulations. |

| E2 Our company builds and maintains data centers designed with environmental sustainability in mind. |

| E3 Our company actively works to protect the environment. |

| E4 Our company utilizes data centers that contribute to reducing greenhouse gas emissions (carbon dioxide). |

| Social from Piao et al. [59]. |

| S1 Our company protects the job security and rights of its employees. |

| S2 Our company establishes policies to safeguard consumers. |

| S3 Our company strives to achieve mutual growth with our business partners. |

| S4 Our company engages in social contribution activities to support local communities. |

| Governance from Daugaard [60]. |

| G1 Our company works to protect the rights of our shareholders. |

| G2 Our company is committed to practicing ethical management on a continuous basis. |

| G3 Our company makes ongoing efforts to improve corporate governance. |

| G4 Our company is dedicated to preventing bribery and corruption. |

| Organizational trust from Jun [62] and Jung et al. [11]. |

| OT1 I believe our company offers trustworthy products and services. |

| OT2 I believe our company ensures the safety of its products and services. |

| OT3 I believe our company provides products and services that effectively meet customer needs. |

| OT4 I believe our company delivers products and services of superior quality. |

| Organizational commitment from Kang [67] and Kang [66]. |

| OC1 I feel a sense of belonging and ownership in the company where I work. |

| OC2 I feel affection and attachment to my company. |

| OC3 I feel as though the company’s problems are my own. |

| OC4 I am proud to work for my company. |

| Organizational performance from Kaplan and Norton [69] and Kim [70]. |

| OP1 Our company’s corporate image is improving. |

| OP2 Trust in our company’s products and services is increasing. |

| OP3 Our company’s products and services are positively recommended to potential customers. |

| OP4 The number of people who wish to reuse our products and services is growing. |

References

- Lee, B.Y. The Significance, Issues, and Strategic Responses of ESG Disclosure. Financ. Res. Brief 2024, 33, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Y.S.; Kim, M.K.; Song, J.S.; Lee, P.Y.; Choi, I.K.; Park, J.W. A Study on the Impact of Corporate ESG Activities on Brand Image, Corporate Trust, and Corporate Performance. Korean J. Bus. Adm. 2024, 37, 1451–1482. [Google Scholar]

- Dakhli, A. Does Financial Performance Moderate the Relationship Between Board Attributes Corporate Social Responsibility in French Firms? J. Glob. Responsib. 2021, 12, 373–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate Social and Financial Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J.; Charles, D.; Oczkowski, E. The Drivers of Climate Change Innovations, Evidence from the Australian Wine Industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.J. ESG Management and the Role of Outside Directors in Korean Listed Companies. Yonsei Law J. 2021, 37, 401–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.R. The Role of Finance to Promote ESG Management of SMEs. Glob. Financ. Rev. 2021, 2, 171–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.H.; Kim, B.S.; Ha, S.Y. The Relationship between Firms’ Environmental, Social, Governance Factors and Their Financial Performance: An Empirical Rationale for Creating Shared Value. Korean Manag. Sci. Rev. 2015, 32, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.C.; Yoo, S.W. A Comparative Study on Employee Communication between Two Companies with Different Cultural Background: Shared values, Clarity in Work and Communication Campaign. J. Public Relat. 2004, 8, 125–161. [Google Scholar]

- KPMG Samjong Accounting Corp. What Should Companies Prepare for the Rise of ESG? Samjong Insight 2021, 74, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, J.H.; Park, H.S. A Study on the Effect of Corporate ESG Activities on Business Performance: Focusing on the Moderating Effect of Corporate Values Perception. Ind. Promot. Res. 2022, 7, 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, C.H.; Kim, T.D.; Shin, S.C. The Trend of Studies Using Non-financial Measures in the Field of Accounting and ESG Issue. Korea Account. J. 2021, 30, 235–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.H.; Seo, J.I.; Nam, Y.S. The Relationship between ESG Management Legitimacy and Corporate Giving: The Moderating Role of Family Executives. J. Korea Ind. Syst. Res. 2022, 27, 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Papalexandris, N. Sustainable Development and the Critical Role of HRM. Stud. Univ. Babes-Bolyai Oeconomica 2022, 67, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.M.; Ju, S.W. A Study on the Effects of Entrepreneurship Environment on Entrepreneurial Will of the MZ Generation and the Moderating Effect of ESG Awareness. Asia-Pac. J. Converg. Res. Interchang. 2023, 9, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.S.; Seo, J.H. An Analysis of The Real Estate Value Influenced by The Characteristics of ESG Management. J. Korea Real Estate Manag. Rev. 2021, 24, 245–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameer, R.; Othman, R. Sustainability Practices and Corporate Financial Performance: A Study Based on the Top Global Corporations. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 108, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Vander, L.C. Green and Competitive: Ending the Stalemate; Harvard Business School Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, D.F. An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, L.T. Trust: The Connecting Link between Organizational Theory and Philosophical Ethics. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 379–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.M.; Lee, M.H. The Impact of Social Responsibility CSR Has on Organizational Trust and Organizational Commitment in Travel Agencies. J. Tour. Manag. Res. 2014, 58, 253–275. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, H.H.; Tan, C.S.F. Toward the Differentiation of Trust in Supervisor and Trust in Organization. Genet. Soc. Gen. Psychol. Monogr. 2000, 126, 241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cook, J.; Wall, T. New Work Attitude Measures of Trust, Organizational Commitment and Personal Need Non-Fulfillment. J. Occup. Psychol. 1980, 53, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G.; Simon, H.A. Organization; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, H.S. Notes on the Concept of Commitment. Am. J. Sociol. 1960, 66, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, T.S.; Organ, D.W. Job Satisfaction and The Good Soldier: The Relationship Between Affect and Employee “Citizenship”. Acad. Manag. J. 1983, 26, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angle, H.L.; Perry, J.L. An Empirical Assessment of Organizational Commitment and Organizational Effectiveness. Adm. Sci. Q. 1981, 27, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. The Measurement and Antecedents of Affective, Continuance, and Normative Commitment to the Organization. J. Occup. Psychol. 1990, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Herscovitch, L. Commitment in the workplace: Toward a general model. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2001, 11, 299–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhu, Y.; Park, C.W. Leader-Member Exchange, Sales Performance, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment Affect Turnover Intention. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2018, 46, 1909–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, A.N.; Lee, H.S. The Effects of Organizational Culture within Airline’s Crew Team on Organizational Commitment the Team and Customer Orientation. Tour. Res. 2017, 42, 193–220. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, C.J.; Smith, K.G. Knowledge Exchange, and Combination: The Role of Human Resource Practices in The Performance of High-Technology Firms. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 544–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, R.E.; McGrath, M.R. The Transformation of Organizational Cultures: A Competing Values Perspective; Frost, P.J., Moore, L.F., Louis, M.R., Lundberg, C.C., Martin, J., Eds.; Organizational culture; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1985; pp. 315–334. [Google Scholar]

- Won, H.S.; Hong, J.H.; Cha, J.H. An Effect on Business Performance of S&M Business CEOs’ Enterpreneurship. J. Bus. Educ. 2015, 29, 309–340. [Google Scholar]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and Financial Performance: Aggregated Evidence from more than 2000 Empirical Studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliwa, Y.; Ahmed, A.; Ahmed, S. ESG Practices and The Cost of Debt: Evidence from EU Countries. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2021, 79, 102097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Ding, J.; Lee, E.S. The Impact of ESG Investments on Corporate Value and Performance-A Comparative Study of Clothing Manufacturing and Service Industries in China. J. Ind. Innov. 2023, 39, 50–66. [Google Scholar]

- Barrymore, N.; Sampson, R.C. ESG Performance and Labor Productivity: Exploring Whether and When ESG Affects Firm Performance. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2021, 1, 13997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. Measuring Corporate Social Responsibility: A Scale Development Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, H.; Park, J.C. The Effect of Corporate Environmental Responsibility Activities on Corporate Performance: Focusing on the Mediating Effect of Trust Types. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 40, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.I. The Effect of ESG Management Activities of Organizational Members of SMEs on Organizational Effectiveness through Organizational Trust and Corporate Entrepreneurship: Focusing on the Electrical and Electronic Industries in Chungnam and Sejong. Innov. Enterp. Res. 2023, 8, 329–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Kim, Y.O. The Effect of ESG Management Activities of Food Service Companies on Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment. J. Ind. Innov. 2023, 39, 132–142. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.R.; Kim, H.D. The Effect of Service Orientation Effort on Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment, and Turnover Intention in Logistics Firms. J. Korea Port Econ. Assoc. 2017, 33, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, T.; Nuttall, R.; Henisz, W. Five Ways that ESG Creates Value. McKinsey Q. 2019, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.S.; Lee, Y.M. The Influence of Employees’ Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility Motives on their Organizational Commitment. Korea Bus. Rev. 2020, 24, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakil, M.H. Environmental, Social and Governance Performance and Financial Risk: Moderating Role of ESG Controversies and Board Gender Diversity. Resour. Policy 2021, 72, 102144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.N.; Han, S.L. The Effect of ESG Activities on Corporate Image, Perceived Price Fairness, and Consumer Responses. Korean Manag. Rev. 2021, 50, 643–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouthier, M.H.; Rhein, M. Organizational Pride and Its Positive Effects on Employee Behavior. J. Serv. Manag. 2011, 22, 633–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, J.S.; Choi, Y.J. A Study on the Organizational Citizenship Behavior of Court Security Officials. Korean J. Ind. Secur. 2020, 10, 175–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bong, J.H.; Lee, S.H. The Effects of Trust on Customer Orientation and Job Performance in Foodservice Industry: Focused on Contingent Workers. Korean J. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 26, 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, S.L.; Rush, M.C. Altruistic Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Context, Disposition, and Age. J. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 140, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Deshpande, S.P. The Impact of Caring Climate, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment on Job Performance of Employees in a China’s Insurance Company. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.S. A Study on the Impact of Organizational Commitment on Workers’ Turnover Intention and Organizational Performance: Based on Analysis of Welfare Organizations in Busan, Korea. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Ventur. Entrep. 2016, 11, 215–225. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, M.Y. The Effects of Fun Management on the Organizational Commitment and Service Innovation Performance in Food Service Industry. Reg. Ind. Rev. 2017, 40, 149–168. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.A.; Eom, W.Y. Perceptual Difference in the Competences and Performance of Roles of HRD Practitioner at Small and Medium Business by Position, Work experience and Educational level. J. Corp. Educ. Talent Res. 2013, 15, 51–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Oh, S.Y.; Park, S.M. A Study on the Relationship between Transformational Leadership in Public Sector and Active Administration of Public Officials: Focused on Behavioral Mediating Effects, Moderating Effects of Recruitment System and Grade. Korean Soc. Public Adm. 2020, 31, 163–197. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, D.A.; Ridgeway, C.L. Decision Making Groups and Teams: An Information Perspective. Bus. Econ. 2006, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I.K.; Kang, S.K. A Study on the Factors Affecting Organizational Innovation Behavior of SMEs: Focused on the Moderate Effect of Work Experience and Rank. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Ventur. Entrep. 2019, 14, 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Piao, X.; Xie, J.; Managi, S. Environmental, Social, And Corporate Governance Activities with Employee Psychological Well-Being Improvement. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugaard, D. Emerging New Themes in Environmental, Social and Governance Investing: A Systematic Literature Review. Account. Financ. 2020, 60, 1501–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.G. The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Organizational Trust and Commitment to Customer Service in Service Corporate. Korea J. Bus. Adm. 2006, 19, 1867–1893. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, S.H. An Empirical Study on the Effects of SMEs Competition, ESG Management Activities and Organizational Justice on Job Satisfaction: Focusing on Mediating Effects of Self-efficacy. J. Ventur. Innov. 2023, 6, 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa, A.M.S.; Bottomley, P.; Gould-Williams, J.; Abouarghoub, W.; Lythreatis, S. High-Commitment Human Resource Practices and Employee Outcomes: The Contingent Role of Organizational Identification. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2019, 29, 620–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T.; Porter, L.W.; Steers, R.M. Employee-Organizational Linkages: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism, and Turnover; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, R.D.; Lapierre, L.M.; Hausdorf, P.A. Understanding the Links between Work Commitment Constructs. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 58, 392–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, N.Y. The Dual Mediating Effect of Lmx and SNS Information Sharing in The Relationship between E-Leadership and Organizational Commitment. Ph.D. Thesis, Dankook University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, I.T. A Study on the Effect of ESG Management on Financial Performance in Hotel Companies: Focused on Mediating Effects of Authentic Leadership and Affective Organizational Commitment. Ph.D. Thesis, Kyonggi University, Suwon City, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.Y. A Study on The Mediating Effect of Intrapreneurship Between CEO Entrepreneurship and Performance of Manufacturing Enterprise. Ph.D. Thesis, Soongsil University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Norton, D. The Balanced Scorecard—Measures That Drive Performance. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1992, 70, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.H. Effect of Digital Transformation and ESG Management on Corporate Performance. Ph.D. Thesis, Dankook University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.M.; Jeong, H.I. A Study on ESG Management Strategy Case and Promotion Policy—Focusing on the Construction Industry. Logos Manag. Rev. 2023, 21, 169–190. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, P.; Ferris, S.P. Agency Conflict and Corporate Strategy: The effect of Divestment on Corporate value. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.M.; Yang, D.H. Does Firm’s ESG Performance Mitigate the Negative Impact of Agency Costs on Firm Value? Korea Int. Account. Rev. 2022, 104, 135–167. [Google Scholar]

- Eum, S.B.; Kim, H.D.; Kim, D.S. The Relations between Korean KOSDAQ-listed Firm’s ESG Activities, Corporate Performance, and Firm Value. Korean Manag. Consult. Rev. 2023, 23, 219–232. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.H. Legal Issues on the Operation System of Electronic Administrative in Germany. Distrib. Law Rev. 2021, 8, 203–236. [Google Scholar]

- Huh, J.H.; Hong, J.W. The Impact of ESG Management on Customer’s Trust and Satisfaction: Focusing on the Moderating Effect of ESG Concern. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 38, 125–138. [Google Scholar]

- Noh, J.H. The Impact of ESG Management on Job Satisfaction in Transportation Logistics Companies: The Mediating Effects of Organizational Commitment and Self-Efficacy. Korea Trade Rev. 2024, 49, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werther, W.B.; Chandler, D. Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility: Stakeholders in a Global Environment, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, J.S.; Chung, S.H.; Lee, S.R.; Park, J.W. The Effect of ESG Activities on the Business Performance. J. Korean Soc. Aviat. Aeronaut. 2022, 30, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.G.; Lim, S.H. A Study on the Impact of ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) Management Activities of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises on the Organization’s Non-financial Performance. Ind. Promot. Res. 2024, 9, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad, W.M.W.; Wasiuzzaman, S. Environmental, Social and Governance(ESG) Disclosure, Competitive Advantage and Performance of Firms in Malaysia. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2021, 2, 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, Q.A.; Haider, S.; Ali, F.; Jamshed, S.; Ryu, K.; Gill, S.S. Green Human Resource Management Practices and Environ-Mental Performance in Malaysian Green Hotels; The Role of Green Intellectual Capital and Pro-Environmental Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 311, 127504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Olshfski, D. Employee Commitment and Firefighters: It’s My Job. Public Adm. Rev. 2002, 62, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Cho, J.Y. The Study on Receptiveness to Performance Appraisal System Based on BSC Among Public Employees at The Local Level Governments. Korean Soc. Public Adm. 2010, 20, 269–291. [Google Scholar]

| Categories | n(%) | Categories | n(%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 359(64.0) | Department | Planning Team | 40(7.1) |

| Female | 202(36.0) | Sales(Marketing) Team | 154(27.5) | ||

| Age | Twenties | 90(16.0) | Production Control Team | 148(26.4) | |

| Thirties | 82(14.6) | R&D Team | 50(8.9) | ||

| Forties | 164(29.2) | HR Team | 24(4.3) | ||

| Fifties | 176(31.4) | Finance and Accounting Dept. | 61(10.9) | ||

| Above Fifties | 49(8.7) | Others | 84(15.0) | ||

| Academic background | High School Graduate | 118(21.0) | Years of Service | less than 5 years | 109(19.4) |

| College Graduate | 380(67.7) | 5 years or more~ less than 10 years | 158(28.2) | ||

| Above Graduate school | 63(11.2) | ||||

| Job position | Staff | 133(23.7) | 10 years or more~ less than 15 years | 79(14.1) | |

| (rank) | Assistant Manager | 168(29.9) | |||

| Manager | 112(20.0) | 15 years or more | 215(38.3) | ||

| Senior Manager | 72(12.8) | Authenticity of ESG Activity | Y | 381(67.9) | |

| General Manager and above | 76(13.5) | N | 180(32.1) | ||

| Total | 561(100) |

| Construct | Estimate | t-Value | Cronbach‘s ɑ | C.R. | AVE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Std. Estimate | S.E. | ||||||

| Environmental | E4 | 0.766 | 0.875 | 0.977 | 0.731 | ||

| E2 | 1.027 | 0.075 | 16.952 *** | ||||

| Social | S4 | 0.931 | 0.904 | 0.975 | 0.712 | ||

| S3 | 0.903 | 0.040 | 27.299 *** | ||||

| Governance | G4 | 0.742 | 0.920 | 0.977 | 0.731 | ||

| G2 | 0.947 | 0.051 | 23.355 *** | ||||

| G1 | 0.932 | 0.050 | 23.094 *** | ||||

| Organizational Trust | OT4 | 0.802 | 0.917 | 0.977 | 0.727 | ||

| OT2 | 0.906 | 0.048 | 24.505 *** | ||||

| OT1 | 0.893 | 0.049 | 24.187 *** | ||||

| Organizational Commitment | OC4 | 0.553 | 0.824 | 0.976 | 0.720 | ||

| OC3 | 0.815 | 0.120 | 12.199 *** | ||||

| OC2 | 0.838 | 0.125 | 12.158 *** | ||||

| Organizational Performance | OP4 | 0.813 | 0.958 | 0.982 | 0.741 | ||

| OP2 | 0.922 | 0.040 | 26.825 *** | ||||

| OP1 | 0.932 | 0.041 | 27.106 *** | ||||

| Construct | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Environmental | (0.855) | |||||

| (2) Social | 0.662 ** | (0.844) | ||||

| (3) Governance | 0.517 ** | 0.630 ** | (0.855) | |||

| (4) Organizational Trust | 0.475 ** | 0.525 ** | 0.539 ** | (0.853) | ||

| (5) Organizational Commitment | 0.157 ** | 0.262 ** | 0.383 ** | 0.249 ** | (0.849) | |

| (6) Organizational Performance | 0.458 ** | 0.541 ** | 0.611 ** | 0.502 ** | 0.319 ** | (0.861) |

| Hypotheses: Path | Std. Estimate | S.E. | t-Value | p-Value | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1-1: | Environmental | → | Organizational trust | 0.119 | 0.040 | 2.640 ** | 0.005 | Accepted |

| H1-2: | Social | → | 0.225 | 0.057 | 4.149 *** | *** | Accepted | |

| H1-3: | Governance | → | 0.395 | 0.066 | 7.584 *** | *** | Accepted | |

| H2-1: | Environmental | → | Organizational Commitment | −0.096 | 0.041 | −2.402 * | 0.016 | Accepted |

| H2-2: | Social | → | 0.100 | 0.056 | 1.538 | 0.124 | Rejected | |

| H2-3: | Governance | → | 0.340 | 0.066 | 5.490 *** | *** | Accepted | |

| H3-1: | Environmental | → | Organizational Performance | 0.096 | 0.037 | 2.466 * | 0.014 | Accepted |

| H3-2: | Social | → | 0.146 | 0.053 | 2.806 ** | 0.005 | Accepted | |

| H3-3: | Governance | → | 0.352 | 0.066 | 6.519 *** | *** | Accepted | |

| H4: | Organizational Trust | → | Organizational Performance | 0.149 | 0.053 | 3.156 ** | 0.002 | Accepted |

| H5: | Organizational Commitment | → | 0.121 | 0.045 | 3.074 *** | 0.002 | Accepted | |

| Hypotheses: Path | Lower-Job-Position Group (n = 301) | High-Job-Position Group (n = 260) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | t-Value | p-Value | Estimate | t-Value | p-Value | ||||

| H6-1: | Environmental | → | Organizational Performance | 0.105 | 2.071 * | 0.038 | 0.067 | 1.650 | 0.099 |

| H6-2: | Social | → | 0.094 | 1.366 | 0.172 | 0.265 | 3.291 *** | 0.000 | |

| H6-3: | Governance | → | 0.555 | 7.985 *** | 0.000 | 0.176 | 1.530 | 0.126 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, S.-C.; Sung, H.-N.; Shin, J.-I. The Impact of ESG Management Activities on the Organizational Performance of Manufacturing Companies in South Korea: The Moderating Effect of Job Position. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5233. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125233

Jeong S-C, Sung H-N, Shin J-I. The Impact of ESG Management Activities on the Organizational Performance of Manufacturing Companies in South Korea: The Moderating Effect of Job Position. Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5233. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125233

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, Soo-Cheol, Haeng-Nam Sung, and Jae-Ik Shin. 2025. "The Impact of ESG Management Activities on the Organizational Performance of Manufacturing Companies in South Korea: The Moderating Effect of Job Position" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5233. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125233

APA StyleJeong, S.-C., Sung, H.-N., & Shin, J.-I. (2025). The Impact of ESG Management Activities on the Organizational Performance of Manufacturing Companies in South Korea: The Moderating Effect of Job Position. Sustainability, 17(12), 5233. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125233