A Transition Intervention Point System: A Taoist-Inspired Multidimensional Framework for Sustainability Transitions

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Framing the Challenge of Sustainability Transitions

1.2. Addressing the Gaps: Towards an Integrated Framework

1.3. Research Question, Hypothesis, and Proposed Framework

2. Theoretical Synthesis

2.1. Multidimensional Sustainability Study

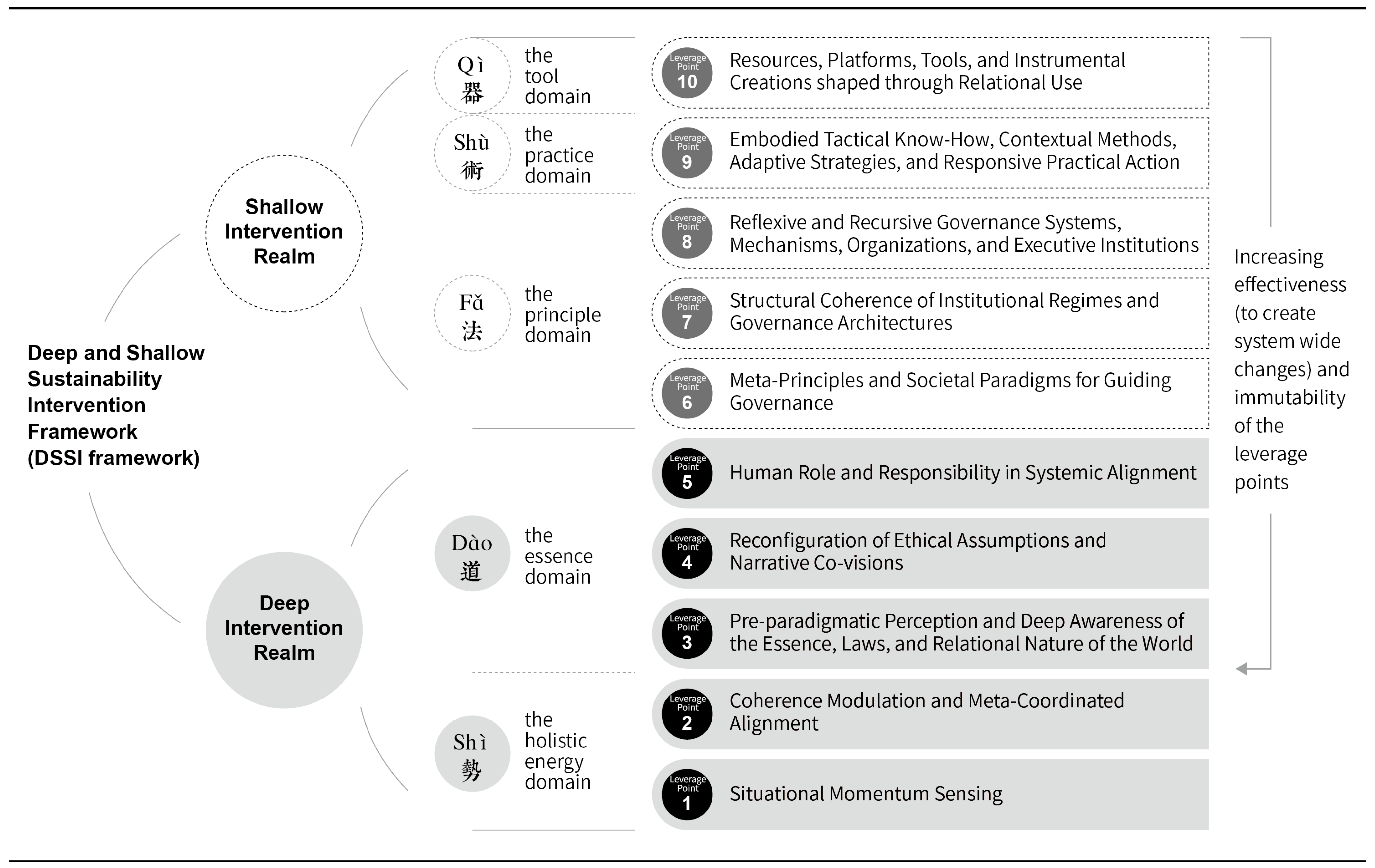

2.2. Core Theoretical Progression: Evolution and Integration of Leverage Points Perspective Research

2.3. Existing Research Gaps and Theoretical Entry Point

3. Methodology

3.1. Step-by-Step Development of the TIP-System

3.2. Case-Based Validation

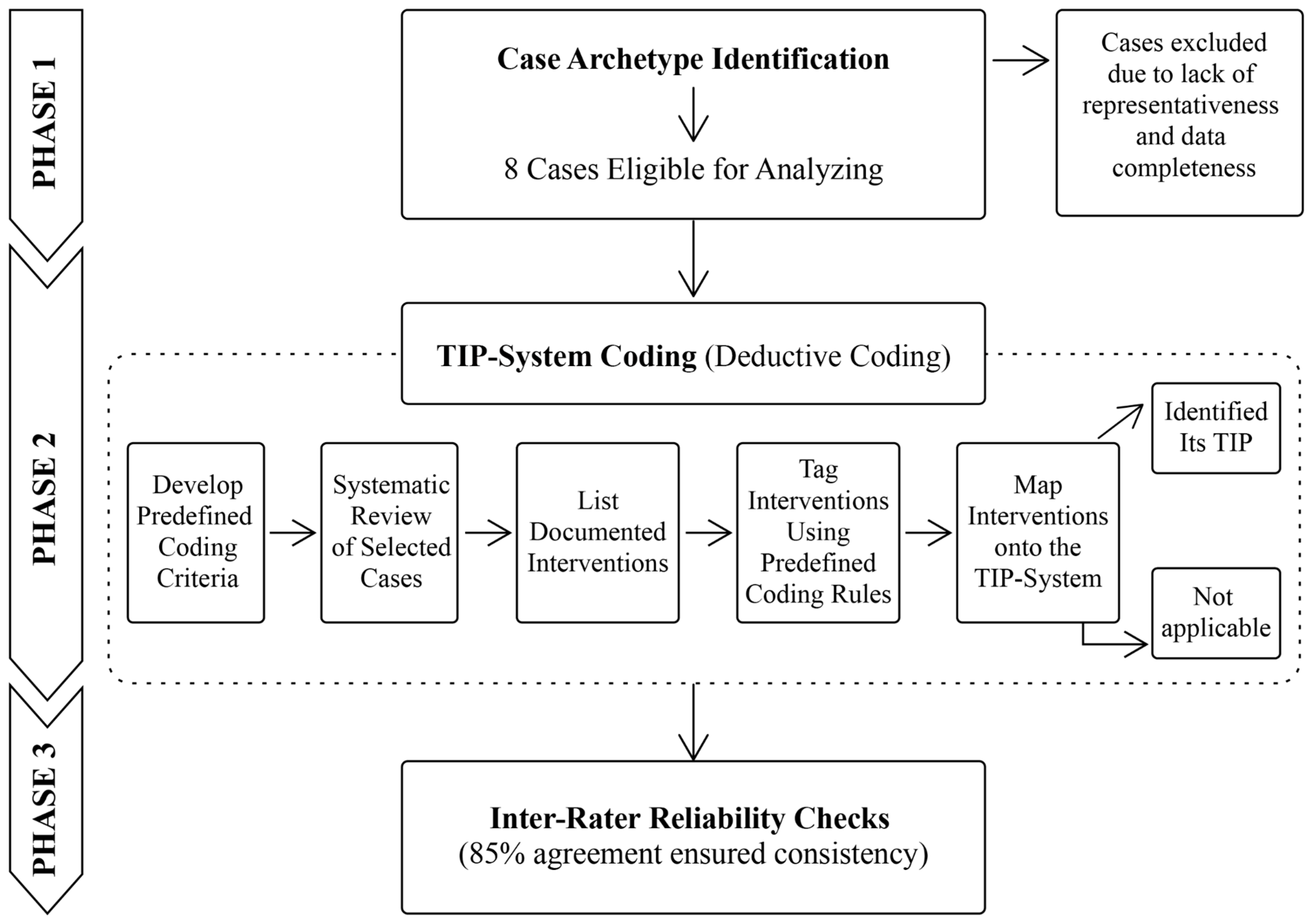

3.2.1. Selection of Case Studies

3.2.2. Three-Phase Validation Protocol

Phase 1. Case Archetype Identification

Phase 2. TIP-System Coding

Phase 3. Pattern Validation

3.3. Limitations of the Methodology

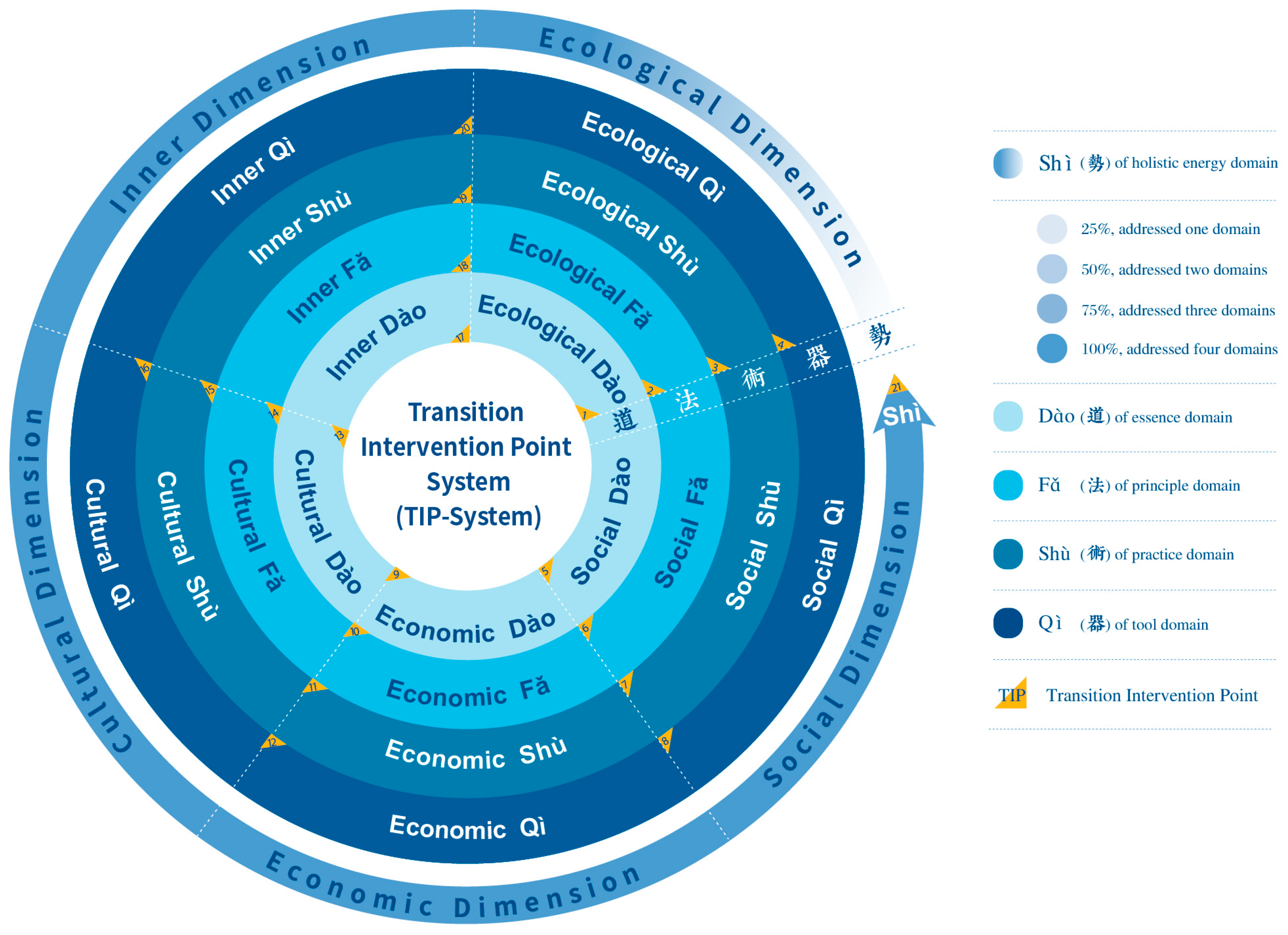

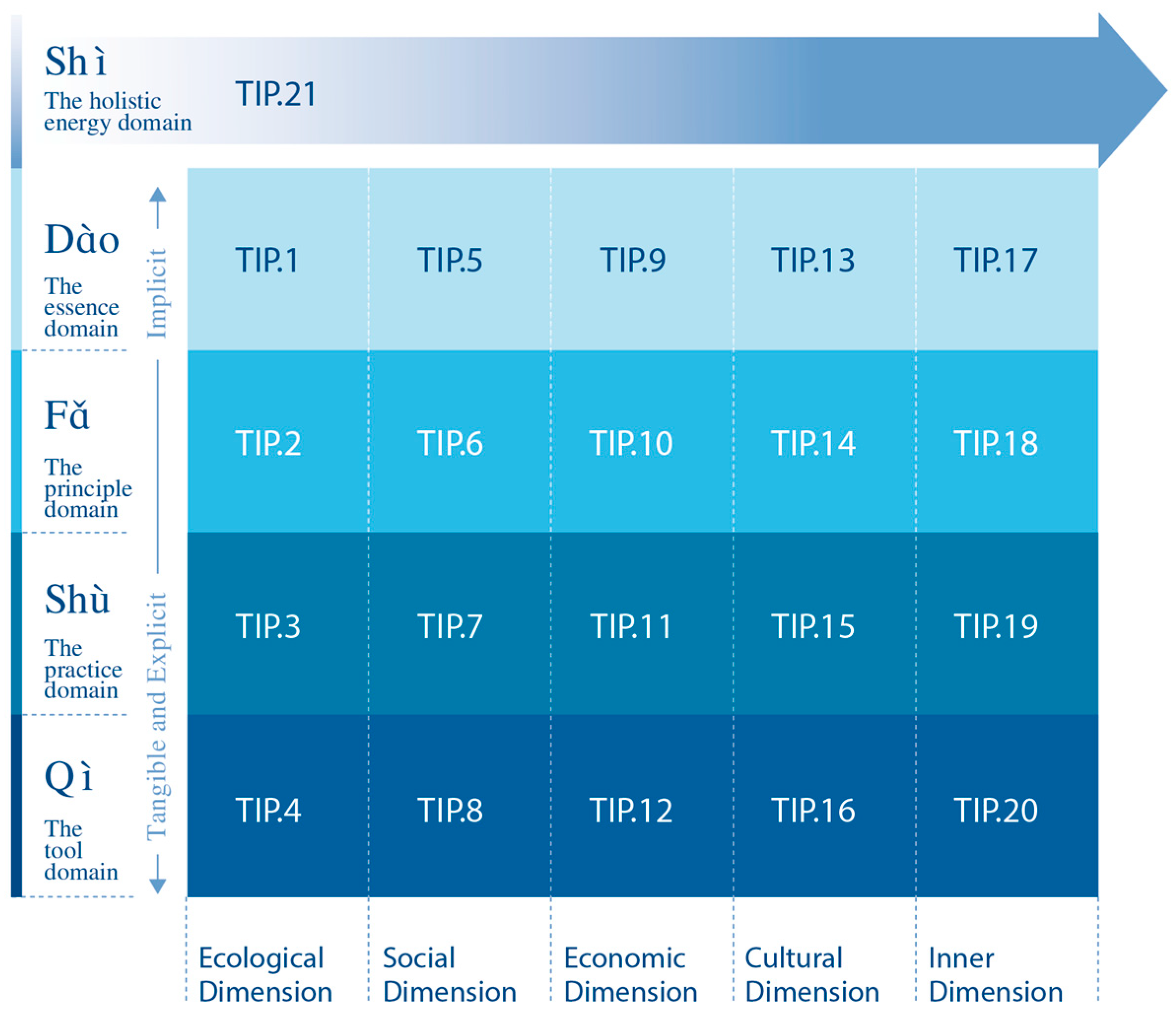

4. Generation of the TIP-System

4.1. Development Formula and Conceptual Foundations

- The essence domain (Dào): The core axioms and paradigmatic foundations of sustainability. It ensures that the transition is grounded in an ethical foundation and shared understanding of humanity’s role and relationship with the Earth, which is critical for fostering collective action and systemic change.

- The principle domain (Fǎ): governance principles, systems, and institutional architectures.

- The practice domain (Shù): adaptive implementation strategies and operational methods.

- The tool domain (Qì): material-technological enablers and physical tools, and resources.

- The holistic energy domain (Shì): System synergy momentum and transformative potential, expressed as “Ψ”, emerges from the dynamic equilibrium of the first four intervention hierarchies, multidimensional feedback loops, and critical thresholds, and the nonlinear interactions among all TIPs. “Ψ” addresses cross-scale coordination, referring to a meta-coordination layer transcending individual TIPs, embodying the Taoist wisdom of ‘generating dynamic equilibrium through holistic synergy’, ensuring that efforts at different levels work together cohesively. Ignoring this domain risks creating fragmented or misaligned actions that fail to address systemic challenges. Interventions in this level refer to “Shì-domain momentum governance”, which is about understanding, identifying, and leveraging the existing dynamics or momentum and potential, “Ψ”, within a system, designing interventions that align with and reinforce the system’s natural flow in a context-aware and adaptive manner. It offers a subtle, flexible perspective, focusing on modulating change, and complements Western transition theories like adaptive governance and systems thinking by emphasizing feedback, emergent change, and multi-level governance.

4.2. TIP-System’s 21 TIPs and Their Functions

4.3. Theoretical Contributions

4.4. Operational Logic Examples and Implementation Suggestions

4.4.1. Operational Logic Examples

4.4.2. A Three-Phase Implementation Approach

Pre-Intervention Phase: Identifying Gaps and Mapping the Current Landscape

Intervention Design: Balancing Deep and Shallow Interventions

Post-Intervention Evaluation: Assessing Outcomes Across Dimensions

5. TIP-System Validation in Case Studies

5.1. The TIP-System for Each of the Eight Social Innovation and Sustainability Initiatives Cases

5.2. Validation Finding

5.2.1. Comprehensive Understanding and Systemic Integration

5.2.2. Identifying Strengths and Gaps for Targeted Support

5.2.3. Fostering Collaboration and Synergy

5.2.4. Evaluating Long-Term Impact

5.3. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Markard, J.; Raven, R.; Truffer, B. Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bergh, J.C.J.M.; Truffer, B.; Kallis, G. Environmental innovation and societal transitions: Introduction and overview. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2011, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.; Geels, F.W.; Kern, F.; Markard, J.; Onsongo, E.; Wieczorek, A.; Alkemade, F.; Avelino, A.; Bergek, A.; Boons, F. An agenda for sustainability transitions research: State of the art and future directions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2019, 31, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. The multi-level perspective on sustainability transitions: Responses to seven criticisms. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2011, 1, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markard, J.; Truffer, B. Technological innovation systems and the multi-level perspective: Towards an integrated framework. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 596–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farla, J.; Markard, J.; Raven, R.; Coenen, L. Sustainability transitions in the making: A closer look at actors, strategies and resources. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2012, 79, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, M.; Schraven, D.; Bocken, N.; Frenken, K.; Hekkert, M.; Kirchherr, J. The battle of the buzzwords: A comparative review of the circular economy and the sharing economy concepts. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2021, 38, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölscher, K.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Loorbach, D. Transition versus transformation: What’s the difference? Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 27, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaa, P.; Laakso, S.; Lonkila, A.; Kaljonen, M. Moving beyond disruptive innovation: A review of disruption in sustainability transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2021, 38, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J.; Schulz, K.; Vervoort, J.; van der Hel, S.; Widerberg, O.; Adler, C.; Hurlbert, M.; Anderton, K.; Sethi, M.; Barau, A.S. Exploring the governance and politics of transformations towards sustainability. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diercks, G.; Larsen, H.; Steward, F. Transformative innovation policy: Addressing variety in an emerging policy paradigm. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 880–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, C.R.; Nakić, V.; Bergek, A.; Hellsmark, H. Transformative innovation policy: A systematic review. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2022, 43, 14–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horcea-Milcu, A.-I.; Abson, D.J.; Apetrei, C.I.; Duse, I.A.; Freeth, R.; Riechers, M.; Lam, D.P.M.; Dorninger, C.; Lang, D.J. Values in transformational sustainability science: Four perspectives for change. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 1425–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J.; Blythe, J.; Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M.; Singh, G.G.; Sumaila, U.R. Just transformations to sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, K.; Sovacool, B.K.; McCauley, D. Humanizing sociotechnical transitions through energy justice: An ethical framework for global transformative change. Energy Policy 2018, 117, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raworth, K. A Safe and Just Space for Humanity: Can We Live Within the Doughnut? Oxfam: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, L.B.; Newig, J. Importance of actors and agency in sustainability transitions: A systematic exploration of the literature. Sustainability 2016, 8, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnheim, B.; Sovacool, B.K. Forever stuck in old ways? Pluralising incumbencies in sustainability transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2020, 35, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sareen, S.; Haarstad, H. Digitalization as a driver of transformative environmental innovation. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2021, 41, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukht, R.; Heeks, R. Defining, conceptualising and measuring the digital economy. Int. Organ. Res. J. 2017, 13, 143–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, O.; Laubichler, M.; Lucas, K.; Kröger, W.; Schanze, J.; Scholz, R.W.; Schweizer, P.J. Systemic risks from different perspectives. Risk Anal. 2022, 42, 1902–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfram, M.; Borgström, S.; Farrelly, M. Urban transformative capacity: From concept to practice. Ambio 2019, 48, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abson, D.J.; Fischer, J.; Leventon, J.; Newig, J.; Schomerus, T.; Vilsmaier, U.; von Wehrden, H.; Abernethy, P.; Ives, C.D.; Jager, N.W.; et al. Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio 2017, 46, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzini, E. Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenfeld, J.R. Searching for sustainability: No quick fix. Reflections 2004, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Markard, J.; Truffer, B. Innovation processes in large technical systems: Market liberalization as a driver for radical change? Res. Policy 2006, 35, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markard, J.; Hekkert, M.; Jacobsson, S. The technological innovation systems framework: Response to six criticisms. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2015, 16, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.; Manning, A.D.; Steffen, W.; Rose, D.B.; Daniell, K.; Felton, A.; Garnett, S.; Gilna, B.; Heinsohn, R.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; et al. Mind the sustainability gap. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 621–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruh, G.C. Understanding carbon lock-in. Energy Policy 2000, 28, 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Loorbach, D. Towards governing infrasystem transitions: Reinforcing lock-in or facilitating change? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2010, 77, 1292–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, R.T. Putting Te Back into Taoism. In Nature in Asian Traditions of Thought: Essays in Environmental Philosophy; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Benyus, J.M. Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature; Morrow: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M. Environmentalism: Spiritual, ethical, political. Environ. Values 2006, 15, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, N.K.A.; Mohd Mustamil, N. Ways to maximize the triple bottom line of the telecommunication industry in Malaysia: The potentials of spiritual well-being through spiritual leadership. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2017, 30, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidingsfelder, J.; Beckmann, M. A governance puzzle to be solved? A systematic literature review of fragmented sustainability governance. Manag. Rev. Q. 2020, 70, 355–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, M.; Marvin, S. Intensifying or transforming sustainable cities? Fragmented logics of urban environmentalism. Local Environ. 2017, 22 (Suppl. S1), 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterman, J.D. Sustaining sustainability: Creating a systems science in a fragmented academy and polarized world. In Sustainability Science: The Emerging Paradigm and the Urban Environment; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 21–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, T.; Radcliffe, N. Sustainability: A Systems Approach; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Humrich, C. Fragmented international governance of Arctic offshore oil: Governance challenges and institutional improvement. Glob. Environ. Politics 2013, 13, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, J.A.; Bertiller, R.; Schwick, C.; Müller, K.; Steinmeier, C.; Ewald, K.C.; Ghazoul, J. Implementing landscape fragmentation as an indicator in the Swiss Monitoring System of Sustainable Development (MONET). J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 88, 737–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Avelino, F. Sustainability transitions research: Transforming science and practice for societal change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2017, 42, 599–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W.; Schot, J. The dynamics of socio-technical transitions: A sociotechnical perspective in grin’. In Transitions to Sustainable Development: New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change; Rotmans, J., Schot, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hebinck, A.; Klerkx, L.; Elzen, B.; Kok, K.P.; König, B.; Schiller, K.; Tschersich, J.; van Mierlo, B.; von Wirth, T. Beyond food for thought–Directing sustainability transitions research to address fundamental change in agri-food systems. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2021, 41, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macy, J.; Brown, M.Y. Coming Back to Life: Practices to Reconnect Our Lives, Our World; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 1998; p. 190. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl, D.C. Design for human and planetary health: A transdisciplinary approach to sustainability. Manag. Nat. Resour. Sustain. Dev. Ecol. Hazards 2006, 99, 285. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, W. Foundations of Futures Studies: Human Science for a New Era: Values, Objectivity, and the Good Society; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Mooney, H.; Hull, V.; Davis, S.J.; Gaskell, J.; Hertel, T.; Lubchenco, J.; Seto, K.C.; Gleick, P.; Kremen, C.; et al. Systems integration for global sustainability. Science 2015, 347, 1258832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H. Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System; The Sustainability Institute: Stellenbosch, South Africa, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H. Dancing with systems. Whole Earth 2001, 106, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in Systems: A Primer; Chelsea Green Publishing: Chelsea, VT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, N.; Segalas, J. Taoist-inspired principles for sustainability transitions: Beyond anthropocentric fixes and rethinking our relationship with nature. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D. Embodying Tao in the ‘restorative university’. Sustain. Sci. 2015, 10, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, M.E. Ecological themes in Taoism and Confucianism. Bucknell Rev. 1993, 37, 150. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, N.; Segalas, J. A Deep and Shallow Sustainability Intervention Framework: A Taoist-Inspired Approach to Systemic Sustainability Transitions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A.L. Strengths and weaknesses of common sustainability indices for multidimensional systems. Environ. Int. 2008, 34, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naegler, T.; Becker, L.; Buchgeister, J.; Hauser, W.; Hottenroth, H.; Junne, T.; Lehr, U.; Scheel, O.; Schmidt-Scheele, R.; Simon, S.; et al. Integrated multidimensional sustainability assessment of energy system transformation pathways. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Darren, R. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvamsdal, S.F.; Eide, A.; Ekerhovd, N.-A.; Enberg, K.; Gudmundsdottir, A.; Hoel, A.H.; Mills, K.E.; Mueter, F.J.; Ravn-Jonsen, L.; Sandal, L.K.; et al. Harvest control rules in modern fisheries management. Elementa 2016, 4, 000114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalampira, E.S.; Nastis, S.A. Back to the future: Simplifying Sustainable Development Goals based on three pillars of sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. Agric. Manag. Inform. 2020, 6, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.J.; Hanson, M.E.; Liverman, D.M., Jr. Global sustainability: Toward definition. Environ. Manag. 1987, 11, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, G. The concept of environmental sustainability. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1995, 26, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Basiago, D.A. Economic, social, and environmental sustainability in development theory and urban planning practice. Environmentalist 1999, 19, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, L. Envisioning sustainability three-dimensionally. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1838–1846. [Google Scholar]

- Schoolman, E.D.; Guest, S.J.; Bush, F.K.; Bell, R.A. How interdisciplinary is sustainability research? Analyzing the structure of an emerging scientific field. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermunt, D.A.; Negro, S.O.; Van Laerhoven, F.S.J.; Verweij, P.A.; Hekkert, M.P. Sustainability transitions in the agri-food sector: How ecology affects transition dynamics. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2020, 36, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S., III; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherr, S.J.; McNeely, J.A. Biodiversity conservation and agricultural sustainability: Towards a new paradigm of ‘ecoagriculture’ landscapes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 477–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, W.C.; Munn, R.E. Sustainable Development of the Biosphere; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Medvigy, D.; Wofsy, S.C.; Munger, J.W.; Moorcroft, P.R. Responses of terrestrial ecosystems and carbon budgets to current and future environmental variability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 8275–8280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, R.A. Balancing the global carbon budget. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2007, 35, 313–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmayer, D.B.; Margules, C.R.; Botkin, D.B. Indicators of biodiversity for ecologically sustainable forest management. Conserv. Biol. 2000, 14, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, G.J.; McDonald, M.E. Application of ecological indicators. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2004, 35, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.L. From protected spaces to hybrid spaces: Mobilizing A place-centered enabling approach for justice-sensitive grassroots innovation studies. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2023, 47, 100726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Contreras, G.A.T.; Brisbois, M.C.; Lacey-Barnacle, M.; Sovacool, B.K. Inclusive innovation in just transitions: The case of smart local energy systems in the UK. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2023, 47, 100719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, J.; Dujon, V.; King, M.C. (Eds.) Understanding the Social Dimension of Sustainability; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Vallance, S.; Perkins, H.C.; Dixon, J.E. What is social sustainability? A clarification of concepts. Geoforum 2011, 42, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, R.L. 12 Social sustainability, sustainable development and housing development. In Housing and Social Change: East-West Perspectives; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Volume 221. [Google Scholar]

- Benkler, Y. Sharing nicely: On shareable goods and the emergence of sharing as a modality of economic production. Yale Law J. 2004, 114, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D.A.; Huffenreuter, R.L. Exploring the economic crisis from a transition management perspective. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2013, 6, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenken, K.; Schor, J. Putting the sharing economy into perspective. In A Research Agenda for Sustainable Consumption Governance; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, S. A critique on current paradigms of economic ‘growth’ and ‘development’ in the context of environment and sustainability issues. Consilience 2016, 16, 74–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Naredo, J.M. In search of lost time: The rise and fall of limits to growth in international sustainability policy. Sustain. Sci. 2015, 10, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Common, M.S. Sustainability and Policy: Limits to Economics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, B. UNESCO and the ‘right’ kind of culture: Bureaucratic production and articulation. Crit. Anthropol. 2011, 31, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurse, K. Culture as the fourth pillar of sustainable development. Small States Econ. Rev. Basic Stat. 2006, 11, 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Soini, K.; Birkeland, I. Exploring the scientific discourse on cultural sustainability. Geoforum 2014, 51, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cities, U.; Governments, L. Agenda 21 for Culture; Committee on Culture–United Cities and Local Governments: Barcelona, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, I.; Baba, S. Shades of cultural marginalization: Cultural survival and autonomy processes. Organ. Theory 2024, 5, 26317877231221552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruijn, E.; Whiteman, G. That which doesn’t break us: Identity work by local indigenous ‘stakeholders’. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 479–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sou, G. Sustainable resilience? Disaster recovery and the marginalization of sociocultural needs and concerns. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2019, 19, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.N.; Sharifi, A. Who are marginalized in accessing urban ecosystem services? A systematic literature review. Land Use Policy 2024, 144, 107266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiktor-Mach, D. What role for culture in the age of sustainable development? UNESCO’s advocacy in the 2030 Agenda negotiations. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2020, 26, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Culture|2030 Indicators; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2019; ISBN 978-92-3-100355-4. [Google Scholar]

- Roseland, M. Toward Sustainable Communities: Solutions for Citizens and Their Governments; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes, J. The Fourth Pillar of Sustainability: Culture’s Essential Role in Public Planning; Common Ground: Champaign, IL, USA; Cultural Development Network: Melbourne, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wilber, K. Sex, Ecology, Spirituality: The Spirit of Evolution; Shambhala Publications: Boulder, CO, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wilber, K. A Theory of Everything: An Integral Vision for Business, Politics, Science and Spirituality; Shambhala Publications: Boulder, CO, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Annick, H.W. Worldviews and their significance for the global sustainable development debate. Environ. Ethics 2013, 35, 133–162. [Google Scholar]

- Annick, H.W.; Joop, B.D.; Boersema, J.J. Exploring inner and outer worlds: A quantitative study of worldviews, environmental attitudes, and sustainable lifestyles. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 37, 40–54. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, J.; Koole, S.L.; Pyszczynski, T. (Eds.) Handbook of Experimental Existential Psychology; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Asoka, M. Social Capital Formation and Institutions for Sustainability; University of British Columbia: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kenter, J.O.; O’Brien, L.; Hockley, N.; Ravenscroft, N.; Fazey, I.; Irvine, K.N.; Reed, M.S.; Christie, M.; Brady, E.; Bryce, R.; et al. What are shared and social values of ecosystems? Ecol. Econ. 2015, 111, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, R.W.; Steiner, G. The real type and ideal type of transdisciplinary processes: Part I—Theoretical foundations. Sustain. Sci. 2015, 10, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.R.; Wiek, A.; Sarewitz, D.; Robinson, J.; Olsson, L.; Kriebel, D.; Loorbach, D. The future of sustainability science: A solutions-oriented research agenda. Sustain. Sci. 2014, 9, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlings, L.G. The inner dimension of sustainability: Personal and cultural values. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedy, C. Terraforming ourselves: A causal layered analysis of interior transformation. In Proceedings of the ‘Transformation in a Changing Climate’: International Conference, Oslo, Norway, 19–21 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Riedy, C. Interior transformation on the pathway to a viable future. J. Futures Stud. 2016, 20, 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Horlings, I.; Frans, P. Leadership for sustainable regional development in rural areas: Bridging personal and institutional aspects. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 21, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, C.D.; Freeth, R.; Fischer, J. Inside-out sustainability: The neglect of inner worlds. Ambio 2020, 49, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K. Global environmental change III: Closing the gap between knowledge and action. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2013, 37, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, P.D. The mindset and posture required to engender life-affirming transitions. In Proceedings of the Transition Design Symposium: Provocation and Position Papers, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 17–19 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.L.; Maris, V.; Simberloff, D.S. The need to respect nature and its limits challenges society and conservation science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 6105–6112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C.; Brossmann, J.; Hendersson, H.; Kristjansdottir, R.; McDonald, C.; Scarampi, P. Mindfulness in sustainability science, practice, and teaching. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C. Education for sustainability: Fostering a more conscious society and transformation towards sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 112–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenni, S.; Soini, K.; Horlings, L.G. The inner dimension of sustainability transformation: How sense of place and values can support sustainable place-shaping. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieckmann, M. Learning to transform the world: Key competencies in Education for Sustainable Development. Issues Trends Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 39, 39–59. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives. UNESCO Digital Library. 2017. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Manning, L.; Ferris, M.; Narvaez Rosario, C.; Prues, M.; Bouchard, L. Spiritual resilience: Understanding the protection and promotion of well-being in the later life. J. Relig. Spiritual. Aging 2019, 31, 168–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmayer, L.J.; Sehdev, M.; Whitley, R.; Dandeneau, S.F.; Isaac, C. Community resilience: Models, metaphors and measures. Int. J. Indig. Health 2009, 5, 62–117. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, J.; Ledogar, R.J. Resilience and indigenous spirituality: A literature review. Pimatisiwin 2008, 6, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Laing, R.D. The Politics of Experience; Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Westley, F.R.; Tjornbo, O.; Schultz, L.; Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Crona, B.; Bodin, Ö. A theory of transformative agency in linked social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naess, A. Ecology, Community and Lifestyle: Outline of an Ecosophy; Rothenberg, D., Ed.; Rothenberg, D., Translator; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, W.J. The historical roots of our ecologic crisis. Science 1967, 155, 1203–1207. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley, M.J. Leadership and the New Science, 1st ed.; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lama, D. Ethics for the New Millennium; Penguin: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, D.W. Four challenges of sustainability. Conserv. Biol. 2002, 16, 1457–1460. [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer, J. The effect of empathy in proenvironmental attitudes and behaviours. Environ. Behav. 2003, 39, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J. Ecovillages: New Frontiers for Sustainability; Schumacher Briefing; Chelsea Green Publishing: Chelsea, VT, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, J. From Islands to Networks—The History and Future of the Ecovillage Movement. In Environmental Anthropology Engaging Ecotopia: Bioregionalism, Permaculture, and Ecovillages; Veteto, J.R., Lockyer, J., Eds.; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 217–235. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, M.A.; Loureiro, C.F.B.; Chevitarese, L.; Souza, C.D.M.E. The meaning and relevance of ecovillages for the construction of sustainable societal alternatives. Ambiente Soc. 2017, 20, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sverdrup, H.; Svensson, M.G. Defining the concept of sustainability-a matter of systems thinking and applied systems analysis. In Systems Approaches and Their Application: Examples from Sweden; Kluwer Academic Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 143–164. [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann, M.; Schaltegger, S.; Landrum, N.E. Sustainability management from a responsible management perspective. In Research Handbook of Responsible Management; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 122–137. [Google Scholar]

- Kaljonen, M.; Kortetmäki, T.; Tribaldos, T.; Huttunen, S.; Karttunen, K.; Maluf, R.S.; Niemi, J.; Saarinen, M.; Salminen, J.; Vaalavuo, M.; et al. Justice in transitions: Widening considerations of justice in dietary transition. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2021, 40, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meireis, T.; Rippl, G. Cultural Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Turcu, C. Re-thinking sustainability indicators: Local perspectives of urban sustainability. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2013, 56, 695–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.C.; Paul, B.A. Sustainable construction: Principles and a framework for attainment. Constr. Manag. Econ. 1997, 15, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorninger, C.; Abson, D.J.; Apetrei, C.I.; Derwort, P.; Ives, C.D.; Klaniecki, K.; Lam, D.P.; Langsenlehner, M.; Riechers, M.; Spittler, N.; et al. Leverage points for sustainability transformation: A review on interventions in food and energy systems. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 171, 106570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, S.; Wang, X. How can technology leverage university teaching & learning innovation? A longitudinal case study of diffusion of technology innovation from the knowledge creation perspective. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 15543–15569. [Google Scholar]

- Leventon, J.; Abson, D.J.; Lang, D.J. Leverage points for sustainability transformations: Nine guiding questions for sustainability science and practice. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.A.; Boyd, D.R.; Gould, R.K.; Jetzkowitz, J.; Liu, J.; Muraca, B.; Naidoo, R.; Olmsted, P.; Satterfield, T.; Selomane, O.; et al. Levers and Leverage Points for pathways to sustainability. People Nat. 2020, 2, 693–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPBES. Global Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-947851-20-1. [Google Scholar]

- Riechers, M.; Loos, J.; Balázsi, Á.; García-Llorente, M.; Bieling, C.; Burgos-Ayala, A.; Chakroun, L.; Mattijssen, T.J.M.; Muhr, M.M.; Perez-Ramirez, I.; et al. Key advantages of the leverage points perspective to shape human-nature relations. Ecosyst. People 2021, 17, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birney, A. How do we know where there is potential to intervene and leverage impact in a changing system? The practitioners perspective. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 749–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.; Riechers, M. A Leverage Points perspective on sustainability. People Nat. 2019, 1, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, C.D.; Abson, D.J.; Von Wehrden, H.; Dorninger, C.; Klaniecki, K.; Fischer, J. Reconnecting with nature for sustainability. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1389–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiren, T.S.; Riechers, M.; Bergsten, A.; Fischer, J. A leverage points perspective on institutions for food security in a smallholder-dominated landscape in southwestern Ethiopia. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, J.; Thomson, G. Learning as a key leverage point for sustainability transformations: A case study of a local government in Perth, Western Australia. Sustain Sci. 2020, 16, 795–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manlosa, A.O.; Schultner, J.; Dorresteijn, I.; Fischer, J. Leverage points for improving gender equality and human well-being in a smallholder farming context. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proust, K.; Newell, B.; Brown, H.; Capon, A.; Browne, C.; Burton, A.; Dixon, J.; Mu, L.; Zarafu, M. Human health and climate change: Leverage points for adaptation in urban environments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 2134–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davelaar, D. Transformation for sustainability: A deep leverage points approach. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 727–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansoff, H.I. Managing strategic surprise by response to weak signals. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1975, 18, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaziulusoy, I.; Veselova, E.; Hodson, E.; Berglund, E.; Öztekin, E.E.; Houtbeckers, E.; Hernberg, H.; Jalas, M.; Fodor, K.; Litowtschenko, M.F. Design for Sustainability Transformations: A ‘Deep Leverage Points’ Research Agenda for the (Post-)pandemic Context. Strateg. Des. Res. J. 2021, 14, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvan, R.; Bennett, D. Taoism and Deep Ecology. Ecologist 1988, 18, 148–159. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN). Sustainable Development Report 2021: The Decade of Action for the Sustainable Development Goals; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenau, J.N. Globalisation and governance: Sustainability between fragmentation and integration. In Governance and Sustainability; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 20–38. [Google Scholar]

- Derani, C. Ethical Issues Raised by Carbon Taxing Regimes. In The Routledge Handbook of Applied Climate Change Ethics; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 263–275. [Google Scholar]

- Maina-Okori, N.M.; Koushik, J.R.; Wilson, A. Reimagining intersectionality in environmental and sustainability education: A critical literature review. J. Environ. Educ. 2018, 49, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, S. The ethical and ecological limits of sustainability: A decolonial approach to climate change in higher education. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2019, 35, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, A.A.; Burgoine, T.; Stamp, E.; Grieve, R. The foodscape: Classification and field validation of secondary data sources across urban/rural and socio-economic classifications in England. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, P.; Newell, P. Sustainability transitions and the state. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 27, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAfee, K. Selling nature to save it? Biodiversity and green developmentalism. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 1999, 17, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borras, S.M., Jr.; Hall, R.; Scoones, I.; White, B.; Wolford, W. Towards a better understanding of global land grabbing: An editorial introduction. J. Peasant. Stud. 2011, 38, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, B.; Borras, S.M.; Hall, R.; Scoones, I.; Wolford, W. The new enclosures: Critical perspectives on corporate land deals. In The New Enclosures: Critical Perspectives on Corporate Land Deals; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Fairhead, J.; Leach, M.; Scoones, I. Green grabbing: A new appropriation of nature? J. Peasant. Stud. 2012, 39, 237–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranski, M. The Globalization of Wheat: A Critical History of the Green Revolution; University of Pittsburgh Press: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Massai, L. The long way to the Copenhagen accord: Climate change negotiations in 2009. Rev. Eur. Community Int. Environ. Law 2010, 19, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhurst, N.; Pataki, G. WP4 CASE Study Report: The Transition Movement TRANSIT: EU SSH. 2015. Available online: http://www.transitsocialinnovation.eu/resource-hub/transition-towns (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Kunze, I.; Flor, A. Social Innovation and the Global Ecovillage Network [Research Report, TRANSIT: EU SSH.2013.3.2-1 Grant Agreement No. 613169]. 2015. Available online: http://www.transitsocialinnovation.eu/resource-hub/global-ecovillage-network-gen (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Cipolla, C.; Joly, M.P.; Afonso, R. WP4: Case Study Report: [DESIS Network]. 2015. Available online: http://www.transitsocialinnovation.eu/resource-hub/desis-network-design-for-social-innovation-and-sustainability (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Saskia, R.; Adrian, S. WP 4|CASE Study Living Labs [TRANSIT: EU SSH.2013.3.2-1 Grant Agreement No. 613169]. 2016. Available online: http://www.transitsocialinnovation.eu/resource-hub/european-network-of-living-labs (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Hopkins, R. The Power of Just Doing Stuff: How Local Action Can Change the World; Bloomsbury Publishing: Dublin, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| External sustainability dimensions | Ecological interventions | Safeguarding the integrity, vitality, and resilience of natural ecosystems as the basis for all life, including human society, emphasizing harmony and collaboration with nature, environmental justice, and regenerative practices that ensure future generations inherit a thriving planet. |

| Social interventions | Creating the foundations for just, inclusive, and thriving societies by supporting human dignity, social cohesion, collective well-being, and participatory governance, recognizing the interdependence of individuals, communities, and institutions, and fostering systems that promote equity, resilience, and care across generations. | |

| Economic interventions | Designing and maintaining economic systems that are ecologically bounded, socially equitable, and structurally resilient, ensuring activities support long-term well-being, regenerating natural systems, and distributing resources fairly by prioritizing sufficiency, care, and circularity. | |

| Cultural interventions | Ensuring the vitality, continuity, and creative evolution of diverse cultures, worldviews, and knowledge systems, while fostering mutual respect for and dialogue and co-existence with diverse cultures, traditions, values, and knowledge systems. | |

| Internal sustainability dimension | Inner interventions | Fostering inner transformation through self-awareness, mindfulness, compassion, and emotional resilience, empowering individuals in aligning values with action, and cultivating the inner conditions necessary for meaningful, long-term transformation in the self, society, and the planet. |

| Transnational Network | Overview | Approach | Local Initiative Cases | Rationale for Selection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition Movement | A movement of Community-led Transition groups, its network has spread now to over 48 countries, with more than 1100 grassroots communities working on local resilience since 2005. | Transition principles (values) balance between head, heart, and hands, and 8 principles. Participatory methods. | Case 1: Transition Town Totnes (UK) | Pioneer in community-led transition, the longest running (September 2006–present) and exemplary Transition initiative. |

| Case 2: Transition Wekerle (Hungary) | The first grassroots transition initiative in Hungary (launched in 2008, re-named in 2011), demonstrating adaptation to post-socialist contexts. | |||

| DESIS Network (Design for Social Innovation and Sustainability) | A global network of 48 design labs supporting ‘social innovation towards sustainability’, originating from 2006–2008 period, based in design schools and design-oriented universities (DESIS Labs), is actively involved in promoting and supporting sustainable change via design practice. | Use design thinking and design knowledge to trigger, enable, and scale-up social innovation, promoting the design community, and the higher education institutions with a design discipline play a pivotal role as agents of change. | Case 3: DESIS—POLIMI DESIS Lab (Italy) | Urban design-driven innovation in the Global North. Its research activity played a leading role in the historical development of network theory and practice. |

| Case 4: DESIS—NAS DESIGN DESIS Lab (Brazil) | Highlights Global South applicability. Studies issues related to social innovation, responsible design, creative communities, and sustainability. | |||

| Global Ecovillage Network (GEN) | A formal network of the ecovillage movement, founded in 1995, and made up of about 10,000 communities and related projects. It is a network of sustainable communities and initiatives that bridges different cultures, countries, and catalyzes communities for a regenerative world. | A holistic regenerative approach that empowers ecovillages cooperatively design for ecological, economic, social, and cultural vitality, through courses and workshops. | Case 5: Ecovillage Schloss Tempelhof (Germany) | Holistic sustainability model. A young but extremely fast-growing project with 140 members, started in 2007. |

| Case 6: Ecovillage Tamera (Portugal) | Founded in 1994, the largest ecovillage in Portugal with 170 members. | |||

| European Network of Living Labs (ENoLL) | A formal network with a membership structure that started in 2006, the community of Living Labs with a sustainable strategy for enhancing innovation on a systematic basis, supporting co-creative, human-centric and user-driven research, development and innovation. | Public–Private–People Partnerships for user-driven open innovation. A user-centric research methodology for sensing, prototyping, validating, and refining solutions through creative processes. | Case 7: Living Lab Eindhoven (Netherlands) | Urban sustainability experimentation. Since 2010, a collection of initiatives has already applied the spirit and method of the Living Lab. |

| Case 8: Living Lab Manchester (UK) | One of Living Lab MDDA was a founding member of ENoLL, created in 2002. Demonstrates policy-industry collaboration in urban contexts |

| Liang and Segalas’ DSSI Framework [55] | External Sustainability | Internal Sustainability | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention Realms | Leverage domains | Ecological Dimension | Social Dimension | Economic Dimension | Cultural Dimension | Inner Dimension |

| Deep intervention realm | Shì (the holistic energy domain) | TIP 21 The dynamic, emergent, cross-dimensional momentum that emerges when all intervention levels align and work synergistically, creating systemic transformation potential. It is operationalized through the activation of multidimensional interventions (Level 1), their purposeful integration (Level 2), and the emergence of systemic momentum and coherence (Level 3). The presence of Shì suggests that the initiative has moved beyond fragmented approaches toward an integrative, self-organizing transition trajectory. | ||||

| e.g., a regenerative city prototype integrating ecological design (e.g., agroecology, watershed stewardship), economic equity (e.g., circular solidarity economies), community co-governance (e.g., inclusive and deliberative processes), cultural creativity (e.g., Indigenous knowledge, intercultural plural storytelling) and inner development (e.g., mindfulness, compassion-based leadership). Over time, the initiative demonstrated signs of emergent systemic momentum that create a field effect—a whole is greater than the sum of its parts where the system begins to self-regulate, self-amplify, and exhibit resilience, generating holistic transition momentum. | ||||||

| Dào (the essence domain) | TIP 1 Foundational ecological worldviews and cosmologies shaping how nature and ecological balance is understood and valued. | TIP 5 Core worldviews and civilizational axioms about human nature, social relations, and collective well-being. | TIP 9 Ethics basis, foundational worldviews and civilizational axioms about the purpose, operation and nature of the economy. | TIP 13 Core worldviews and cosmologies that define cultural meaning, identity, and humanity’s relationship with nature and each other. | TIP 17 Paradigmatic basis, foundational beliefs and worldviews about consciousness, the self, and the inner-outer connection. | |

| e.g., affirming humanity’s embeddedness within nature’s interconnected web, recognizing ecological balance as the non-negotiable foundation for all life; symbiosis in harmony, holistic ecological thinking. | e.g., affirming human dignity, equity, and interdependence as irreducible axioms for societal well-being and collective stewardship; socially inclusive, trust, shared future for all, equality in essences. | e.g., embracing sufficiency, reciprocity, and equity as economic paradigms, prioritizing well-being over GDP, rejecting infinite growth paradigms, and the economy as a subsystem of ecology. | e.g., affirming epistemic pluralism, preservation of intergenerational wisdom, and cultural sovereignty, and that diverse knowledge systems hold equal validity, such as human responsibility, harmony and love. | e.g., inner transformation as the root of outer change, non-dualistic regenerative paradigms of interbeing, the self as interconnected, not separate from others or the Earth. | ||

| Shallow intervention realm | Fǎ (the principle domain) | TIP 2 Ecological ethics and guiding principles, policies, laws, governance systems that enforce ecological justice, resilience, and alignment with natural laws. | TIP 6 Social values, ethics and normative grounding that govern inclusion, justice, equity, participation, and solidarity. | TIP 10 Economic principles, value commitments and institutional governance to guide sustainable economies, redistribution and circular value creation. | TIP 14 Cultural ethics, value commitments and normative principles guiding inclusion, respect, and coexistence in plural societies. | TIP 18 Inner values, normative logics and ethical commitments that guide personal growth and relational well-being. |

| e.g., Constitutional Rights of Nature clauses, regenerative ethics charters, EU Green Deal, biodiversity offsetting regulations, planetary boundaries treaties | e.g., equity-based social paradigms, participatory governance, respect principles and caring relations, anti-oppression legal frameworks, human rights declarations, anti-discrimination laws. | e.g., redesigning economic structures, regulations, incentives and governance systems, self-reliant local economy system, ethical trade agreements, extended producer responsibility (EPR) laws. | e.g., cultural paradigms and mechanisms, Indigenous land sovereignty declarations, UNESCO intangible heritage protocols, traditional knowledge IP rights, multilingual education policies. | e.g., inner ethical grounding, mindset, personal values and normative logics, interconnectedness and relational accountability, compassion, empathy, and loving-kindness as moral imperatives. | ||

| Shù (the practice domain) | TIP 3 Adaptive approaches, ecological design strategies, and regenerative frameworks for restoring ecosystems and harmonising human activities with biophysical limits. | TIP 7 Sustainable practices, solutions, strategic approaches and methods for building inclusive, empowered, cohesive and resilient communities. | TIP 11 Systemic strategies, practices and institutional design approaches for transforming economic systems and localized and regenerative value chains. | TIP 15 Institutional or community strategies, approaches, practices and processes that apply cultural ethics, values and principles to action. | TIP 19 Practices, methods and plans for cultivating inner awareness and transformation. | |

| e.g., agroecology and permaculture design methods, renewable energy strategies, rewilding, watershed or bioregional planning, agroforestry, coral reef rehabilitation, nature-based solutions. | e.g., co-design and participatory planning in public services, empowerment strategies, cooperative governance model, intergenerational skill-sharing programs, intentional communities and cohousing models. | e.g., doughnut economics frameworks, circular economy strategies, sustainable consumption plan, community-supported agriculture (CSA), industrial symbiosis networks, ethical blockchain supply chains. | e.g., intercultural dialogue frameworks for peacebuilding, community-based cultural revitalization programs, participatory heritage mapping that links culture, place, and identity, transdisciplinary design integrating local art, ritual, and storytelling. | e.g., interventions fostering self-awareness, emotional resilience, or spiritual connection to nature, such as, ecopsychology practices for inner-outer alignment, growth mindset method, values-based training. | ||

| Qì (the tool domain) | TIP 4 Ecological infrastructures, resources, policy instruments, technical tools and monitoring systems for ecological health and regenerative transitions. | TIP 8 Social tools, technologies, platforms, resources and policy instruments that operationalize social sustainability, collaboration and sharing. | TIP 12 Economic policy tools, metrics, infrastructures and technologies for transparent, equitable transactions and resource flow optimization. | TIP 16 Systems, technologies, tools, mechanisms and spaces that enable cultural sustainability practices. | TIP 20 Tools, platforms, and systems that support inner development and transformation at scale. | |

| e.g., air quality sensors, agro ecological equipment, rainwater harvesting systems, biochar production systems, rewilded urban parks and ecological corridors, regenerative farms using closed-loop systems. | e.g., complete infrastructure, community cohesion, social impact measurement tools, open-source mutual aid platforms, community-led disaster response apps, neighborhood resilience hubs, and community centers. | e.g., solidarity economy networks, circular economy platforms, alternative currency, time-banking systems, exchange services, AI-driven circular design platforms, decentralized renewable energy trading systems. | e.g., community museums, open-source cultural toolkits for educators and planners, digital archives and platforms preserving endangered languages and traditions, such as, digital oral history archives, AR/VR platforms for virtual heritage. | e.g., intentional communities that foster collective inner growth and culture of care, rites of passage programs reconnecting people to land, ancestors, and self, retreat centers, self-cultivation techniques, well-being apps. | ||

| TIP Coordinate | Intervention Levels | Operational Definition | Sustainability Transition Operationalization |

|---|---|---|---|

| TIP21 {Ψ: System momentum—Shì} | Holistic energy domain, refers to system synergy holistic momentum and potential | Emergent ecological properties from nonlinear system interactions | An emergent, system-level outcome that integrates and amplifies the effects of individual ecological interventions, resulting in a comprehensive enhancement of ecosystem resilience |

| TIP1 {d1—Eco, l1—Dào} | Essence domain, refers to ethical–cognitive schema and meta-paradigm architecture | Deep ecological value paradigms and ontological commitments | Paradigmatic reframing, e.g., reconceptualizing human–nature relationships and restructuring ecological cognition via planetary boundaries theory |

| TIP2 {d1—Eco, l2—Fǎ} | Principle domain, refers to institutional symbiosis and coupling governance system | Complementary institutional architecture ensuring eco-dimensional goal alignment | Institutional design, e.g., complementary design of ecological redlines and market mechanisms |

| TIP3 {d1—Eco, l3—Shù} | Practice domain, refers to fluid adaptive responses, dynamic practical method, and strategies to context | Context-sensitive dynamic ecological intervention strategies | Adaptive management method, e.g., dynamic water allocation based on real-time ecosystem diagnostics |

| TIP4 {d1—Eco, l4—Qì} | Tool domain, refers to value-embedded techniques, instruments, and resources | Eco-technological artifacts | Technological embodiment, e.g., biomimetic urban infrastructure, water monitoring sensors, and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) |

| Intervention Realm | Realm of Leverage | Ecological Dimension | Social Dimension | Economic Dimension | Cultural Dimension | Inner Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep intervention realm | Shì (the holistic energy domain) | TIP 21—the holistic energy Shì e.g., a looser network of projects working around transition based themes (a relaxed approach), which adhere in some way to the overall goals of transition | ||||

| Dào (the essence domain) | TIP1—ecological essence Dào. e.g., towards ‘a more enriching and gentler perspective on the earth than the way most of us live today’ | TIP5—social essence Dào. e.g., well-being, justice, and a collectively produced vision, which argues for the need a societal shift towards a more ecologically sustainable future | TIP9—economic essence Dào. e.g., put ‘new economic’ values at the heart, contributing to enhancing local economic resilience | TIP13—cultural essence Dào. e.g., working collaboratively to build a ‘town that cares’, committed to improve the well-being of people within the locality and caring passionately about the future of the locality | TIP17—inner essence Dào. e.g., Inner transition, the transformation of the values or beliefs of participants | |

| Shallow intervention realm | Fǎ (the principle domain) | TIP2—ecological principle Fǎ. e.g., incorporating permaculture principles into transition approaches, Totnes Renewable Energy Society (TRESOC) | TIP6—social principle Fǎ. e.g., well-being, justice, and a collectively produced vision which argues for the need a societal shift towards a more ecologically sustainable future | TIP10—economic principle Fǎ. e.g., economic blueprint, gift economy model (users pay what they can afford and practically support the day-to-day operations of the center, such as cleaning or contributing in other ways) | TIP14—cultural principle Fǎ. e.g., creating a narrative about how societal change can be facilitated by community mobilization, producing collaborative community based process | TIP18—inner principle Fǎ. e.g., a deeper form of change for broader values and worldviews |

| Shù (the practice domain) | TIP3—ecological practice Shù. e.g., launching the Food-Link project, building good energy partnership, initiating Totnes Energy Descent Action Plan | TIP6—social practice Shù. e.g., offers a set of 21 ‘tools for transition’, using the technique of ‘backcasting’, launch the Caring Town Totnes project to build a different form of social care provision from the bottom up | TIP11—economic practice Shù. e.g., ‘Totnes Pound Local Currency’ system (first paper based local currency in the UK), TRESOC (an Industrial and provident model of community ownership that is specifically focused on being economically self-sustaining) | TIP15—cultural practice Shù. e.g., management “unleashing collective genius”, emphasizes cultural change (public talks and courses at Schumacher College); viewing transition as a cultural process, to nudge the culture and prepare communities for uncertainty and change [175] | TIP19—inner practice Shù. e.g., Transition support and mentoring and well-being of group, an approach that engages with ‘head, heart, and hands’ | |

| Qì (the tool domain) | TIP4—ecological tool Qì. e.g., gardenshare, Follaton Forest Garden, more solar panels are installed on the roofs of the town | TIP8—social tool Qì. e.g., open eco homes fair, free skillshare, traffic and transport forum, publications (e.g., Transition in Action, a powered down, re-localized future for the locality in 2030) | TIP12—economic tool Qì. e.g., Totnes pound, local entrepreneur forum, written guidance such as the published “Transition Companion”, and physical spaces to support new initiatives, such as the REconomy center | TIP16—cultural tool Qì. e.g., transition tours, publications such as ‘Transition Handbook’, websites, transition training, such as ‘Life after Oil Course’; Totnes Arts Network; open public meetings, public talks | TIP20—inner tool Qì. e.g., behavior change intervention, reskilling, individual consumption patterns changing | |

| Intervention Realm | Realm of Leverage | Ecological Dimension | Social Dimension | Economic Dimension | Cultural Dimension | Inner Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep intervention realm | Shì (the holistic energy domain) | TIP 21—the holistic energy Shì As a label for a collection of various collaborative initiatives focusing on social challenges and the use of technology and data in the city | ||||

| Dào (the essence domain) | - | TIP5—social essence Dào. e.g., safety, liveability and attractiveness of the Stratumseind area | - | - | - | |

| Shallow intervention realm | Fǎ (the principle domain) | - | TIP6—social principle Fǎ. e.g., contribute to a dynamic European Innovation System | - | TIP14—cultural principle Fǎ. e.g., innovative institutional arrangement relation with actors/initiatives/networks | - |

| Shù (the practice domain) | TIP3—ecological practice Shù. e.g., suggested urban-gardening and producing one’s own (sustainable) energy, feasible, efficient, and environment friendly solutions, such as the Smart Grid and the future ‘Energy Internet’ | TIP6—social principle Shù. e.g., ICT applications in Doornakkers (see Figure 8, the Intervention Initiation Point indicated by the red arrow in Case 7), as a general neighborhood improvement strategy | TIP11—economic practice Shù. e.g., A triple helix (business, government, and knowledge and educational institutions), business innovation, and new business model | TIP15—cultural practice Shù. e.g., embraces technological change, openness, cooperation, the use of data and social media | - | |

| Qì (the tool domain) | - | TIP8—social tool Qì. e.g., The project Stratumseind 2.0, the Smart Light Grid, urbanization, and a focus on prevention, Slimmer Leven 2020 competition | TIP12—economic tool Qì. e.g., bricks-and-clicks and Public–Private–People Partnerships | TIP16—cultural tool Qì. e.g., The Strijp S, Eckhart-Vaartbroek City Studios, Smart Cities publications, workshops and educational activities | TIP20—inner tool Qì. e.g., attempt to connect people and start dialogues, and interventions of individuals | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liang, N.; Segalas, J. A Transition Intervention Point System: A Taoist-Inspired Multidimensional Framework for Sustainability Transitions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5204. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115204

Liang N, Segalas J. A Transition Intervention Point System: A Taoist-Inspired Multidimensional Framework for Sustainability Transitions. Sustainability. 2025; 17(11):5204. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115204

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Na, and Jordi Segalas. 2025. "A Transition Intervention Point System: A Taoist-Inspired Multidimensional Framework for Sustainability Transitions" Sustainability 17, no. 11: 5204. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115204

APA StyleLiang, N., & Segalas, J. (2025). A Transition Intervention Point System: A Taoist-Inspired Multidimensional Framework for Sustainability Transitions. Sustainability, 17(11), 5204. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115204