1. Introduction

The importance of sustainability has steadily grown, both in terms of corporate strategies [

1] and individual behaviors [

2]. With the rise of various social issues and environmental crises worldwide, philanthropic giving has gained significant attention. A clear manifestation of this growing interest among businesses is the rising number of foundations (e.g., Microsoft Philanthropies, IKEA Foundation) dedicated to philanthropic activities [

3]. These entities are not only advancing corporate social responsibility but are also actively involved in volunteerism and charitable initiatives [

4]. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs), in turn, serve as a vital channel for individuals to participate in volunteer work and charitable activities, thus empowering personal engagement in social change [

5]. With the development of various digital tools—most notably digital platforms—NGOs are leveraging these technologies to support and expand their socially driven missions.

The emergence of international multisided digital platforms resulted in the development of various forms of crowdsourcing (e.g., crowdfunding, crowd design, knowledge sharing). Renard and Davis [

6] (p. 186) define crowdsourcing as “an organizational strategy that outsource a function once performed by employees to an undefined, generally large network of people by inviting ideas and contributions, typically from volunteers over the Internet”. Bakici [

7] considers it a form of open innovation that serves to gather creative ideas or solutions from external sources. In the literature, there are also very narrow definitions of crowdsourcing, e.g., those referring to it as consumers’ input in a new product’s development through idea generation [

8]. Another type of crowdsourcing that has been increasingly discussed is crowdfunding [

9]. Choy and Schlagwein [

10] (p. 221) say that crowdfunding is “an IT-enabled process of collecting relatively small contributions or donations from a large number of people online”. Belleflamme et al. [

11] define crowdfunding as an open invitation, generally via the Internet, to provide financial resources in the form of donations or in exchange for monetary or non-monetary rewards to support initiatives for specific purposes. Crowdfunding campaigns are typically hosted on digital crowdfunding platforms and take different forms, such as reward-based, equity-based, lending-based, and donation-based (charity-based) [

12].

Crowdfunding platforms have emerged as popular tools for fundraising, frequently utilized by charities to mobilize resources for causes driving social sustainability [

13], allowing individuals to contribute easily and collectively make a meaningful impact. Examples of popular crowdfunding platforms used for charity fundraising include GoFundMe, Crowdrise, Fundly, and DonorsChoose. Moreover, crowdfunding platforms inherently support social inclusion by allowing people from diverse regions and backgrounds to contribute to projects that align with their values and social identities. This promotes sustainable community development by creating a platform for collective participation in addressing social issues and directly supports social sustainability by fostering shared responsibilities for societal welfare [

10]. Researchers focus mostly on commercial crowdfunding and its motivations. For instance, Rossi [

14] writes about funding new products and business ventures, while much less literature can be found on charitable crowdfunding and donors’ motivations [

10]. In this study, we concentrate on the pure donation model of crowdfunding (charitable crowdfunding), which is defined as contributing money without the possibility of receiving material benefits, as opposed to other forms of donation crowdfunding, in which donors can receive material compensation, for example [

15]. Knowledge of the motivations behind charitable giving is critical to the success of the marketing strategies of nonprofit organizations (NGOs) aimed at attracting charitable donations.

Furthermore, culture and tradition play a pivotal role in shaping the patterns of volunteerism and charitable behavior, which differ significantly across various regions of the world. In many societies, the acts of giving and community service are deeply rooted in religious beliefs, moral values, and long-standing social norms. For instance, in Islamic cultures, the concept of zakat (obligatory almsgiving) and sadaqah (voluntary charity) are central to philanthropic engagement, while in Western contexts, charitable donations are often institutionalized and linked to organized civil society [

16]. Similarly, in East Asian countries, collective responsibility and community cohesion—often influenced by Confucian values—drive voluntary action [

3]. These culturally embedded practices influence not only the motivation to give but also the mechanisms through which people contribute, such as informal support networks, formal foundations, or digital platforms. Understanding these cultural dimensions is essential for developing effective global strategies for civic engagement and philanthropic outreach.

In summary, charitable crowdfunding is an emerging and dynamic ontological phenomenon. Because of the full dependence of crowdfunding platforms on the voluntary action of their users, it is crucial to understand what motivates users to take part in such activities [

17]. Despite evidence that national and individual culture can influence consumers’ behaviors, including their social involvement, few studies explore this phenomenon [

18].

By addressing this research gap and referring to Self-Determination Theory (SDT), this study aims to determine if consumers’ individual culture profiles, i.e., one’s cultural orientation based on values, attitudes, and behaviors declared by individuals in the survey, differentiate their motivations and engagement in charitable giving in digital crowdfunding platforms. Considering that individual cultural values tend to be associated with the dominant national culture, we compare residents of different world regions. The differentiation between motivations, along with regional variations, highlights the complexity of charitable giving as a sustainable behavior. Connecting this to the broader concept of sustainability, particularly social sustainability, reveals how fostering collective action can align with sustainable development goals and address global challenges.

This paper offers three key contributions to the literature on charitable giving. First, it adopts a novel perspective by examining how consumers’ individual cultural profiles influence their donation motivations and engagement levels on digital charitable platforms. Second, moving beyond the predominantly Western-centric or single-country focus of the existing research, this study employs a cross-cultural, cross-regional approach, enabling a more granular understanding of regional variations in motivational drivers and painting a more globally relevant picture of charitable behavior. Third, this paper positions charitable crowdfunding not just as a fundraising mechanism but as a facilitator of social sustainability and collective action aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

This paper is structured as follows: it starts with a critical literature review concerning cultural values and motivations behind charitable giving on crowdfunding platforms, and their connection with charitable crowdfunding. Then, we present the conceptual model, research methods, and findings. We conclude with a discussion of the theoretical contributions, practical implications, limitations, and suggestions for further research.

2. The Interplay Between Charitable Giving, Social Sustainability, and Personal Well-Being

One of the most urgent challenges confronting societies today is the pursuit of ecological, economic, and social sustainability [

19]. The UN’s World Commission on Environment and Development [

20] called for balancing environmental, economic, and social equity to ensure long-term fairness across generations and defined sustainable development as meeting present needs without compromising future generations, emphasizing it as a core principle for governments, institutions, and businesses. In response to this need, 193 UN member states adopted 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in September 2015, aiming to end poverty, safeguard the planet, and promote prosperity for all within a global sustainable development framework [

21].

Social sustainability encompasses three key processes: assessing environmental impacts, managing stakeholders, and addressing social issues [

22,

23]. Furthermore, social sustainability refers to the creation of inclusive and equitable social systems that support human well-being and resilience across generations [

24]. Charity, particularly in regions with low government social support, acts as an alternative mechanism to support vulnerable communities. As sustainability requires social systems that prevent exclusion and promote equity, donation-based crowdfunding can complement state welfare programs and enhance the resilience of marginalized groups [

25]. The beneficiaries of charitable giving can be individuals, communities, or institutions, promoting sustainable social outcomes. Donations to non-governmental organizations, like UNICEF, promote sustainable human development by addressing critical issues, such as child welfare, education, and poverty reduction [

26].

Engaging in prosocial behaviors, such as donating to charity, is closely linked to individual and societal well-being [

27], contributing directly to sustainable development through the promotion of social equity and resilience. Charitable giving can enhance personal happiness, with individuals who allocate a greater portion of their income to prosocial causes experiencing higher levels of life satisfaction than those who prioritize personal expenditures [

28]. This connection between giving and well-being illustrates how sustainable development is not only about environmental and economic stability but also about fostering social well-being and inclusive growth.

However, sustainable charitable giving faces challenges, particularly during periods of economic instability [

29]. During recessions and crises, consumers tend to become more cautious, prioritizing their immediate needs and reducing expenditures on non-essential items, including donations and ethical consumption. One way to maintain prosocial behavior as a driver of sustainable development is to create systemic support for philanthropic activities, even in economically challenging times. Public policies, tax incentives, and awareness campaigns could ensure that charitable giving remains an integral component of sustainable development [

25]. However, perhaps even more important is our understanding of the attitudinal and behavioral antecedents of charitable engagement. By addressing potential systemic barriers and supporting these behaviors with an in-depth understanding of underlying psychological factors and possible cultural differences, societies can create resilient social systems aligned with long-term sustainability objectives. Through this research, we try to assist with this task.

3. Charitable Crowdfunding and Cultural Values

Cultural values are often linked with national culture, understood as “a glue that binds people” [

30] (p. 38) or a set of all beliefs, customs, morals, and other habits and capabilities that one acquires as a member of a given society [

31]. Importantly, they are among the factors influencing consumer behavior [

18]. The boundaries between cultures are gradually blurring as cultures increasingly intermingle in the course of the acculturation process [

32]. The differences in consumer behavior across countries resulting from cultural influences are also identified when consumers are not aware of them [

33].

As culture is a multidimensional and interdisciplinary phenomenon [

34], authors propose various dimensions to be included in research. However, those proposed by Hofstede [

35] are still frequently used in empirical studies, as well as in studies of consumer behavior [

36,

37,

38]. According to the original Hofstede model [

35], cultural dimensions encompass power distance (expectations towards and acceptance of unequal distribution of power), uncertainty avoidance (tolerance for ambiguity, whether one feels comfortable or not in unstructured situations), individualism versus collectivism (the extent to which members of a society are integrated into groups), and masculinity versus femininity (distribution of values between genders). Next, additional dimensions were added, including long-term versus short-term orientation (with long-term orientation focusing on the future, perseverance, and delays in gratification for future benefits) and indulgence versus restraint (with the first allowing for free gratification related to the enjoyment of life and second focused on keeping gratification under control) [

37]. Although Hofstede’s dimensions of culture are frequently employed in consumer behavior studies, the approach faces criticism because such research typically focuses on individual-level evaluations of cultural constructs [

39]. However, other scholars [

40] demonstrated the validity of measuring culture at the individual level. They argued that the approach avoids the ecological fallacy when cultural dimension scores reflect respondents’ personal cultural traits (derived from scale items), rather than being assigned based solely on their country of origin. This distinction is important because consumers from the same country may possess differing cultural values and related characteristics. While significant progress has been made in conceptualizing and measuring culture, a need remains for continued development, particularly regarding methods that assess cultural dimensions at the individual level [

41]. Addressing this need, Yoo et al. [

42] developed the CVSCALE, a 26-item, 5-dimensional scale designed to measure individual cultural values based on Hofstede’s model. This scale assesses five dimensions, including power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism/collectivism, masculinity/femininity, and long-term/short-term orientation, thereby enabling the examination of cultural variations among individuals within a nation. Importantly, the CVSCALE has demonstrated adequate reliability, validity, and generalizability across diverse nations and samples. Subsequently, Ar and Kara [

43] created a similar, albeit shorter, 20-item, 4-dimensional scale. Their instrument retained four core Hofstede dimensions: power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism/collectivism, and masculinity/femininity. Ar and Kara [

43] also provided evidence supporting their scale’s reliability and validity. Thus, findings from such studies indicate that utilizing modified Hofstede-based scales at the individual consumer level is a justified approach [

44].

To date, relatively little research attention has focused on the relationship between cultural differences and engagement in prosocial activities, such as charitable giving. Analyzing secondary data from dozens of countries, Bernardino and Santos [

18] found that national culture shapes crowdfunding activities. Specifically, among Hofstede’s dimensions, individualism and long-term orientation were positively associated with crowdfunding, whereas uncertainty avoidance showed a negative association. Similarly, using secondary data from several countries, Luria et al. [

33] reported that only uncertainty avoidance positively predicted charitable giving, while other Hofstede dimensions predicted different prosocial activities, such as volunteering.

Investigating the influence of social norms, Siemens et al. [

45] found that norms exerted a greater influence on Koreans (representing a collectivist, “tight” society) than on Americans (representing an individualistic, “loose” culture). The authors concluded that the presence of others increased Americans’ inclination to contribute, whereas Koreans’ contributions were unaffected, being driven primarily by an internal motivation to comply with social norms.

Cultural differences may also influence how charitable giving is promoted across countries, for instance, through appeals emphasizing individual versus group accomplishments [

46]. For example, Weiss-Sidi and Riemer [

47] suggested that individualists often associate altruism with self-interest (termed “impure altruism”), helping others partly to enhance their own happiness. Conversely, collectivists tend to focus more on the recipient and an enhancement in the recipient’s well-being. Furthermore, Cai et al. [

48] concluded that individualism can increase charitable donations by encouraging “self-interested giving”. They added that individualistic norms might enhance the personal benefits experienced when contributing to the common good, particularly when such contributions receive public recognition.

Rey-Biel, Sheremeta, and Uler [

49] found no cultural differences in charitable giving between Americans and Spaniards when participants possessed knowledge about factors impacting others’ wealth. However, when participants lacked this information, Spaniards demonstrated a greater willingness to contribute compared to Americans. Furthermore, Nguyen et al. [

50] reported that the intention–behavior gap in charitable giving was similar across Australia, China, and New Zealand.

Much of the research on prosocial acts, including charitable giving and crowdfunding, has predominantly focused on Western countries [

51]. Additionally, studies often consider only a limited set of cultural dimensions, such as collectivism versus individualism [

48]. These limitations may contribute to the sometimes-contradictory conclusions within the literature [

18].

Indeed, as Bernardino and Santos [

18] noted in their literature review, while a considerable body of research discusses crowdfunding, the influence of national culture within this phenomenon is frequently overlooked. Moreover, research examining cultural values as moderating factors in prosocial behavior remains sparse. This gap persists despite suggestions from some researchers [

52] that cultural values can moderate consumer behavior more broadly.

Acknowledging these likely impacts of cultural values on charitable behavior, we hypothesize the following:

H.1: Individual cultural dimensions, including collectivism (H.1.1), power distance (H.1.2), and uncertainty avoidance (H.1.3), are associated with charitable behavior.

4. Motivations Behind Volunteerism and Charitable Giving

Prior research on volunteerism, charitable giving, and participation in crowdsourcing platforms has drawn upon various theoretical frameworks. These include social cognition models like the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [

53] and the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) [

54], as well as value-based theories, such as Value Theory [

55], Expectancy-Value Theory [

56], and Self-Determination Theory (SDT) [

57].

Motivation can be defined as “a process to release, control, and maintain physical and mental activities” [

58] (p. 310). Based on Self-Determination Theory (SDT), Ryan and Deci [

59] distinguish between two primary types:

Intrinsic motivation: Initiating an activity for its inherent interest and satisfaction.

Extrinsic motivation: Engaging in an activity to achieve a separate, external goal.

Building on this, von Krogh, Haefliger, Spaeth, and Wallin [

60] proposed a related classification identifying three groups:

Intrinsic motivations (e.g., ideology, altruism, kinship, fun).

Extrinsic motivations (e.g., career advancement, payment).

Internalized extrinsic motivations: Motivations that are external in origin but become internally valued by the individual (e.g., reputation, reciprocity, learning, own-use value).

Specifically focusing on crowdsourcing participation, Alam et al. [

61] developed a more detailed taxonomy of motivations, categorized as follows:

Intrinsic personal motivations: Including (a) affective components (e.g., fun, enjoyment, curiosity, task autonomy, task identity, pastime, rituals, habit) and (b) personal self-oriented drivers (e.g., interest, learning, personal growth/self-fulfillment, personal taste/preference, own-use).

Intrinsic social motivations: Community-based drivers, such as altruism, kinship, external self-concept (meeting group expectations), reciprocity, and ideology.

Extrinsic personal motivations: Including (a) human capital advancement (e.g., internal self-concept, signaling, career benefits, learning), (b) payment, and (c) rewards (e.g., recognition, reputation, self-expression).

Extrinsic social motivations: Social contact drivers, including (a) indirect benefits (e.g., feedback, diversion, social integration) and (b) direct social opportunities (e.g., socializing, collaboration, advocacy).

Various questionnaires and scales have been employed in research examining the motivations behind volunteerism, charitable giving, and participation in crowdsourcing platforms. Among the most frequently utilized is the Volunteer Functions Inventory (VFI), developed by Clary et al. [

62]. The VFI is widely regarded as a comprehensive and psychometrically sound instrument for assessing volunteer motives [

63] and is noted for its ease of use [

64].

The VFI model posits six core psychological functions that volunteerism (and potentially other prosocial behaviors like charitable giving) can serve, driving an individual’s motivation. These functions include the following:

Values: Expressing altruistic or humanitarian beliefs and values by serving others.

Understanding: Gaining knowledge, skills, or experiences through the activity.

Social: Conforming to the social norms of significant others or enhancing social connections.

Career: Gaining career-related experience or skills.

Protective: Reducing negative feelings or addressing personal problems through distraction or helping others.

Enhancement: Improving self-esteem, self-worth, or personal development.

The standard VFI questionnaire comprises 30 items (5 for each function), typically rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale (e.g., from 1—“not at all important/accurate” to 7—“extremely important/accurate”). It has been widely applied in volunteerism research, for example, [

65].

Several researchers have proposed extensions to the VFI. Drawing on role theory, Penner [

66] added a “Role Identity” scale. Chacón et al. [

65] suggested including “Organizational Commitment”, particularly for predicting long-term volunteerism. Focusing on charitable giving, Esmond and Dunlop [

67] identified additional motivations like “reciprocity”, “reactivity”, and “recognition”, while Katz and Sasson [

68] incorporated “adolescent-specific motivations”.

Reciprocity, in particular, is often highlighted as a critical driver. Khadjavi [

69] linked it to the belief that current receipts are related to past generosity. Zhang et al. [

9] distinguished two types relevant to charitable giving: (1) upstream reciprocity, driven by past positive emotional experiences and the impact of showing kindness, and (2) downward reciprocity, motivated by the expectation of future rewards for good deeds. Supporting its importance, Dawson’s [

70] survey found reciprocity, alongside income, assets, and age, to be a significant predictor of monetary donations to medical research.

Other research explores socially oriented motivations. Charitable giving and crowdfunding donations may stem from a desire to avoid others’ contempt, gain social approval, or stimulate social interactions [

71]. This aligns with the construct of “performance expectancy”, defined by Li et al. [

72] (p. 407) as the belief that donating via a platform will yield personal satisfaction, social interaction, approval, or accomplishment. However, Chen et al. [

73] found that while social influence, altruism, and self-worth affected donation intentions on crowdfunding platforms, performance expectancy did not show a significant effect in their study.

Motivations related to internal feelings and self-perception are also prominent. Gleasure and Feller [

74] confirmed the roles of both “warm glow” (emotional reward from giving) and “pure altruism” in online charitable crowdfunding. Using a lab experiment, Tonin and Vlassopoulos [

75] demonstrated that “self-image” concerns can incentivize charitable giving. Furthermore, Gorczyca and Hartman [

76] found a positive relationship between intrinsic motivation and millennials’ attitudes toward charitable organizations, suggesting approaches like crowdfunding could appeal to this demographic.

Finally, the interplay between intrinsic and extrinsic factors is crucial. Haruvy and Popkowski-Leszczyc [

77] (p. 311) investigated how self-driven (intrinsic) versus monetary (extrinsic) incentives, mediated by effort, affect fundraising outcomes. Their field experiment revealed that high monetary incentives yielded the largest immediate fundraising increase but potentially dampened future volunteering intentions after removal.

Based on the above discussion on the role of motivations in charitable giving, we propose the following:

H.2: Intrinsic (H.2.1) and extrinsic (H.2.1) motivations are associated with charitable behavior.

H.3: Intrinsic (H.3.1) and extrinsic (H.3.2) motivations are moderators in the relationship between national culture and charitable behavior.

Considering that cultural values and motives can manifest differently across demographic groups, and based on the prior literature suggesting the influences of personal factors on charitable giving, we also included several personal characteristics as control variables in our model to isolate the effects of culture and motivation more clearly. In particular, individuals from higher social classes tend to perceive charitable giving as a viable means to address societal challenges, influencing not only their personal giving behaviors but also shaping public discourse and policy regarding philanthropy. Those with more resources often advocate for charity in ways that individuals from lower social classes might not [

78]. Furthermore, factors like income level, age, education, and family structure significantly impact charitable contributions, as revealed by research linking these demographic variables to giving behaviors as statistically significant predictors of charitable donations [

79,

80]. We therefore hypothesized the following:

H.4: Personal characteristics, included as control variables, such as (H.4.1), age (H.4.2), education (H.4.3), region of residence (H.4.4), and income (H.4.5), are associated with charitable behavior.

5. Conceptual Model of This Study

While several cultural dimensions have been proposed and measured at the individual level [

42,

43], this study focuses specifically on collectivism (the counterpart to Individualism), power distance, and uncertainty avoidance for inclusion in the conceptual model. This selection was guided by several factors. Firstly, the prior research on charitable giving and crowdfunding, as reviewed above, has frequently highlighted the relevance of these particular dimensions, suggesting their potential significance in shaping donor behavior in this context, for example, [

18,

33,

45,

81]. Secondly, focusing on these three dimensions allows for a more parsimonious model while still capturing substantial cultural variation relevant to social interactions and risk perception inherent in online donation platforms. While the scale adapted from Ar and Kara [

43] also measures masculinity/femininity, it was excluded from the final model as its direct theoretical link to charitable crowdfunding motivations and behaviors appeared less pronounced in the existing literature compared to the selected dimensions.

In this study, we primarily operationalized motivations for charitable giving based on the framework of the Volunteer Functions Inventory (VFI) developed by Clary et al. [

62].

While the act of volunteering time and effort may differ from donating monetary resources, both represent significant forms of prosocial behavior. The decision to engage in either activity—volunteering or charitable giving—often stems from a common wellspring of human motivations, both intrinsic and extrinsic. Individuals may seek to express core values (e.g., altruism, humanitarianism), enhance their self-esteem or address personal problems (protective and enhancement functions), or conform to social norms and connect with others (social functions) through various helping behaviors. This underlying commonality in motivational drivers means that well-established frameworks for understanding volunteer motivation can also offer valuable insights into the reasons people choose to donate money to charitable causes. The VFI model itself acknowledges that the psychological functions it outlines can drive volunteerism (and potentially other prosocial behaviors like charitable giving). Consequently, models such as the Volunteer Functions Inventory, though originally designed to assess motivations for volunteering, are considered highly relevant for exploring the motivations behind charitable giving, as both involve the allocation of personal resources for the benefit of others or a specific cause.

Following common interpretations linking VFI to Self-Determination Theory, we categorized these motivations as either intrinsic or extrinsic.

For intrinsic motivations relevant to charitable giving via crowdfunding platforms, we included the VFI functions of “values”, “enhancement”, and “protective” (i.e., escaping negative feelings). We excluded the “understanding” function because its focus on gaining knowledge and skills is arguably more applicable to traditional volunteerism than to monetary donations via crowdfunding.

For extrinsic motivations, drawing from the VFI (“social” function) and related extensions in the literature, we included “social” (conforming to the norms of significant others), “reputation” (specifically, perceived reputation within the online community), and “reciprocity” (related to anticipated benefits).

Based on the theoretical framework and the literature discussed in the preceding sections, we developed Hypotheses H1 through H4.

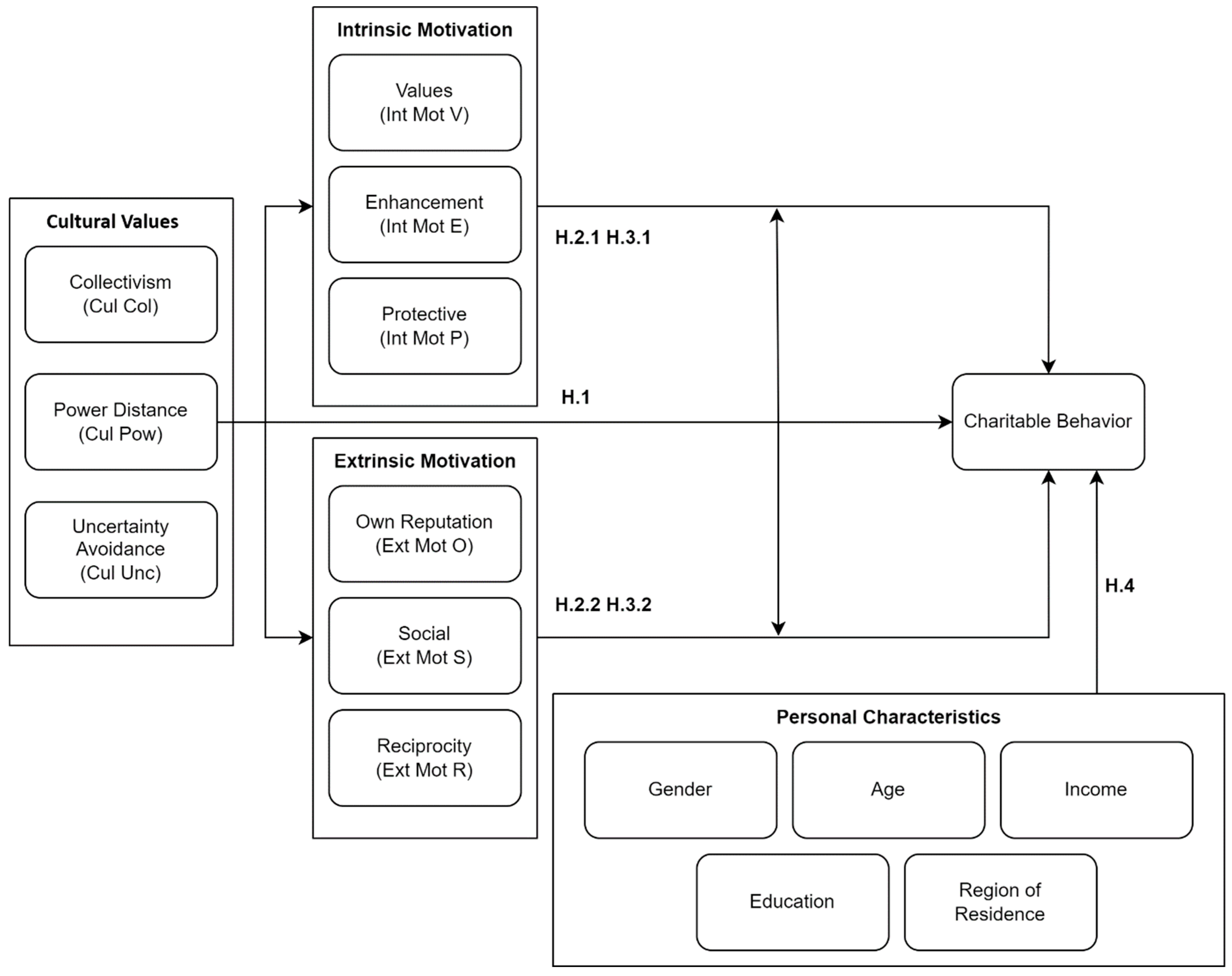

Figure 1 integrates these hypotheses into a conceptual model depicting the proposed relationships between individual cultural values (collectivism, power distance, uncertainty avoidance), intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, charitable behavior, and key personal characteristics included as control variables.

The conceptual model guiding this research (

Figure 1) is substantially informed by Self-Determination Theory (SDT). SDT is a broad framework for the study of human motivation and personality, differentiating motivations along a continuum from autonomous (intrinsic) to controlled (extrinsic) [

59]. A core tenet of SDT is that social–contextual factors, including cultural influences, can enhance or undermine intrinsic motivation and promote different types of extrinsic motivation, partly by influencing the satisfaction of basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

In the context of the current study, the individual cultural values (collectivism, power distance, uncertainty avoidance) included in our model are posited as significant individual-level manifestations shaped by broader socio-cultural contexts. Within an SDT framework, these cultural orientations are conceptualized as influencing an individual’s motivational orientations towards charitable actions, as the broader social environment shapes the internalization and expression of needs and motives.

Our model’s explicit focus on intrinsic motivations (such as acting from one’s values, seeking personal enhancement, or protective reasons) and extrinsic motivations (such as concerns for reputation, social conformity, or reciprocity) directly aligns with the motivational constructs central to SDT. This classification, as detailed in our operationalization of motivations, connects the Volunteer Functions Inventory to these foundational SDT concepts.

Finally, charitable behavior is the key outcome influenced by these differing motivational pathways. SDT helps to explain how these pathways are, in turn, shaped by the cultural backdrop.

Therefore, SDT provides a robust theoretical foundation for our model by explaining how individual cultural values can foster or impede specific intrinsic and extrinsic motivations and how these motivations subsequently predict engagement in charitable behavior.

Research Method

The data for this study were gathered in September–October 2022 through Amazon Mechanical Turk, a global crowdsourcing platform where individuals sign up to perform small jobs, including taking surveys. An online questionnaire was self-administered by the participants, who received payment upon its completion. The participants were prescreened to ensure that only those who donated at least once to a charity through an online platform were eligible. In addition, regional filters were applied to ensure that replies came from a variety of geographical areas. Overall, 680 complete questionnaires were returned.

The sample’s characteristics, encompassing demographics and other relevant attributes, are presented in

Table 1.

The measurement model employed in this study encompassed the following:

- -

Three first-order reflective constructs representing individual culture dimensions;

- -

Two second-order reflective constructs for intrinsic (Int Mot) and extrinsic (Ext Mot) charity motivations.

The scaling of the reflective constructs followed a Likert format, where all composite statements were graded on a 1 to 7 scale, with response possibilities ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”.

Table 2 contains a list of all Likert-scale statements used to measure the reflective constructs.

The conceptual framework of this study also included one formative construct of

charitable behavior (Cha Beh). The interval-scale items for charitable behavior, derived from Knowles et al. [

82], were obtained by asking the following questions:

What is the total amount that you donated in the past year?

What is the % of your income that you are able to give to charity?

What is the number of times that you donated in the past year?

How likely do you think it is that you will donate money to a charitable crowdfunding platform in the next 4 weeks?

The four items used by Knowles et al. [

82] captured both the scale of past donations (amount, frequency) and the intention for near-future giving. While distinct, these facets were aggregated, following standardization, to represent a comprehensive measure of an individual’s tendency towards charitable engagement via online platforms, encompassing both demonstrated commitment and forward-looking propensity.

To assess the research hypotheses, partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS SEM) was performed, using SmartPLS software (version 4.1). SEM analyses were carried out for the entire sample and then separately for regional subsamples of North America, Europe, and South America. The estimated models were evaluated in terms of reliability and validity.

To assess the statistical significance of the path coefficients in the structural model, we employed a non-parametric bootstrapping procedure using 5000 subsamples. Bootstrapping is a non-parametric procedure that randomly draws observations with replacement from the original dataset to create “bootstrapped” samples of equal size. This process was repeated many times (here, 5000), enabling us to estimate robust standard errors and confidence intervals for path coefficients. Such an approach is recommended in PLS-SEM to mitigate potential issues of non-normality and to yield more reliable significance testing [

83].

Overall, employing bootstrapping for significance testing is a robust and widely endorsed statistical technique in the context of PLS-SEM, as recommended by the methodological literature [

83]. Its application is particularly relevant because PLS-SEM, unlike covariance-based SEM, makes minimal distributional assumptions about the data. When data are not normally distributed, as is common in social science research and a condition that PLS-SEM is designed to handle, traditional parametric tests for significance may yield unreliable results. Bootstrapping, as a non-parametric method, empirically derives the sampling distribution by repeatedly drawing observations with replacement from the original dataset to create numerous subsamples. This process allows for the robust estimation of standard errors and confidence intervals for parameters like path coefficients, offering a more trustworthy approach to assess their stability and statistical significance. This ultimately leads to more reliable research conclusions when working with the PLS-SEM framework [

83].

6. Research Findings and Hypothesis Test Results

Reflective latent variables in structural models must be examined for reliability and validity before being used in regression analysis. A measurement model with insufficient reliability and validity is likely to produce difficult-to-interpret constructs and may indicate spurious correlations.

Table 3 shows a set of common metrics used in the evaluation of PLS SEM measurement models.

The reliability of a reflective factor solution can be assessed with average variance extracted (AVE), Cronbach’s alpha, and composite reliability coefficients. An AVE informs of the average amount of variance explained by a latent variable in its indicators, which should be greater than 0.50 [

83] (p. 605). Cronbach alphas provide a measure of the correlations among the indicators of a construct and should exceed 0.7 [

84] (p. 287). Composite reliability offers a metric of internal consistency that, unlike Cronbach’s alpha, is not affected by the number of indicators. For narrowly defined models with five to eight indicators, a recommended minimum value of composite reliability is 0.80 [

85]. Given that these three metrics exceed the recommended thresholds for each latent variable in the measurement model, sufficient reliability is demonstrated.

The Fornell–Larcker criterion [

86] is frequently used to investigate discriminant validity, which posits that latent variables have distinct meanings if their average extracted variance is greater than the maximum shared variance. In other words, a construct should be more strongly correlated with its own indicators than with other latent variables in the model. In the off-diagonal cells,

Table 1 gives bivariate correlation coefficients between pairs of the constructs and average correlations of the constructs with their indicators on the diagonal (i.e., square roots of AVEs). Considering that the diagonal values are greater than the off-diagonal terms, discriminant validity can be claimed.

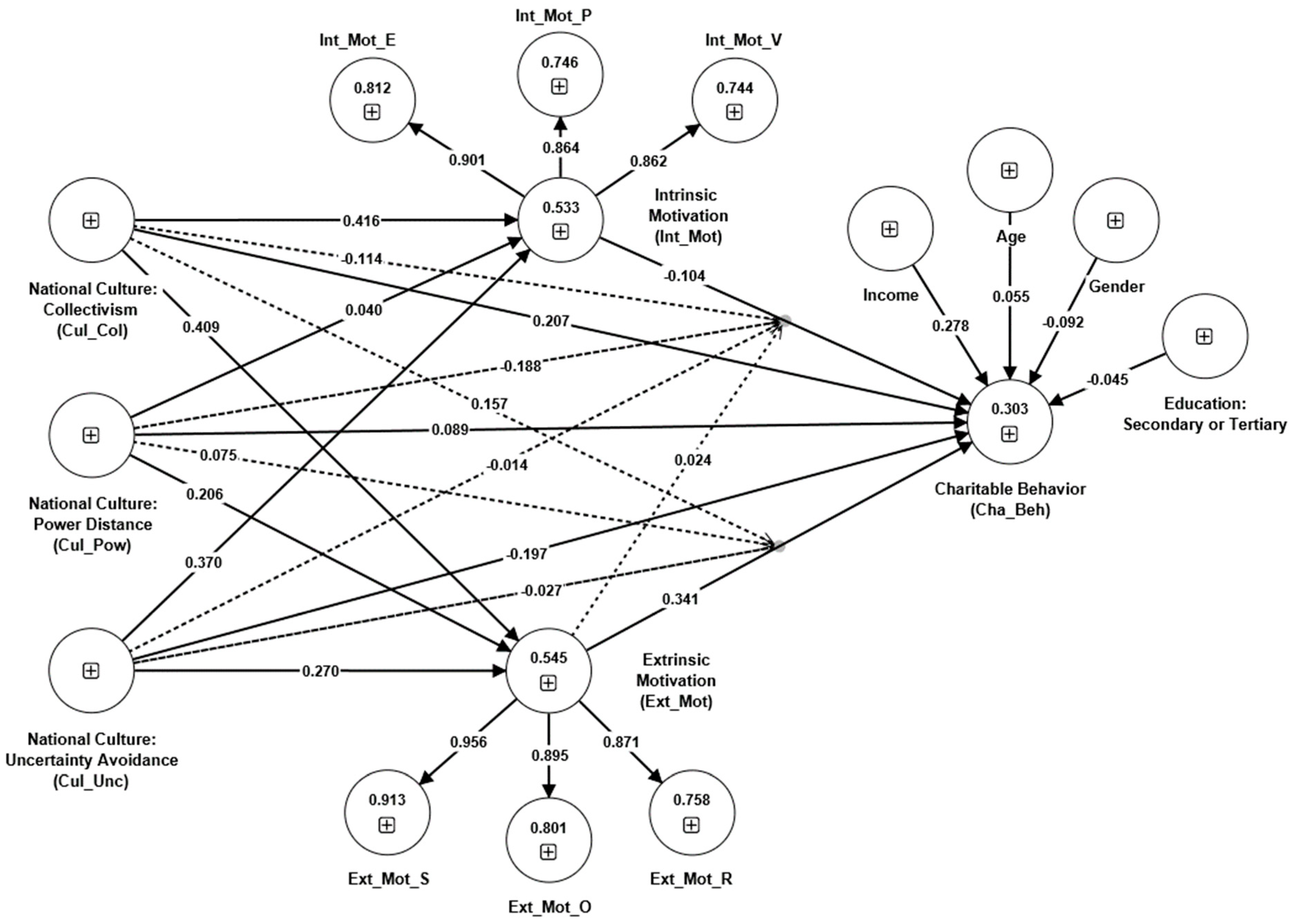

The next step of the analysis focuses on presenting and interpreting the regression weights between the latent and measurable variables in the inner model. The standardized regression weights and coefficients of determination (R-squared) for the entire sample are displayed in

Figure 2.

Table 4 shows the standardized regression weights with bootstrapped

p-values for the complete sample and the three regions of the respondents. Significance was assessed at both the

p < 0.05 and

p < 0.10 levels. While

p < 0.05 indicates strong statistical significance, the results at the

p < 0.10 level are also noted (as shown in

Table 4) to highlight potentially meaningful trends or “marginal significance”, a common practice in social science research, particularly for exploratory analyses or subgroup comparisons with reduced statistical power.

Both

Figure 2 and

Table 4 indicate that individual cultural dimensions are meaningful factors in determining charity behavior. In the entire sample, the direct effect on Cha_Beh is positive for Cul_Col (0.207), negative for Cul_Unc (−0.197), and nonsignificant for Cul_Pow (0.089). Accounting for indirect effects through intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, the positive impact of Cul_Col on Cha_Beh increases to 0.303, while the total effect of Cul_Pow gets stronger and becomes significant (0.155). The total effect of Cul_Unc is slightly weaker than its direct association with Cha_Beh, but it is still significant (−0.143). To have a complete picture of the strength and nature of the relationship between the cultural dimensions and charitable behavior, one must consider their interactions with motives for charitable behavior.

Table 4 suggests that there is only one significant interaction term when analyses are run on the complete sample: Cul_Pow x Int_Mot (−0.188). This interaction can make the total effect of Cul_Pow on Cha_Beh stronger, which occurs when Cul_Pow (a standardized variable with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation equal to 1) takes values below its mean, which are negative, and shifts the sign of the moderation effect from negative to positive. However, for levels of Cul_Pow that are greater than the mean, the contribution to the total effect of the interaction is negative. For example, when Cul_Pow is twice as large as the mean, its value is 2, which turns the total effect from positive to negative (0.155 − 0.376 = −0.221). Overall,

this gives full support to H.1.1 through H.1.3 by demonstrating the significant associations between all three national–culture dimensions and charitable behavior. It seems that the effect of Cul_Col is positive, Cul_Unc negative, and Cul_Pow mixed because of the significant negative interaction with Int_Mot.

Extrinsic motivations have a significant and positive relationship with charitable behavior (0.341), while intrinsic motivations show a nonsignificant and negative direct effect (−0.104). However, through the negative interaction with Cul_Pow (−0.188), this association could become significant and negative if Cul_Pow levels are greater than the average for this variable. In summary, these outcomes give full support to H.2.2 and partially corroborate H.2.1.

The fact that there are significant regression paths leading to Ext_Mot and Int_Mot, and that both Ext_Mot and Int_Mot are significant predictors of Cha_Beh, supports the mediating role of motivation variables in the relationship between cultural dimensions and charitable behavior. Also, the total effects of cultural dimensions on Cha_Beh are different from their direct effects when indirect regression paths leading through Ext_Mot and Int_Mot are considered. However, this mediation effect is only partial because there are still significant direct links between the cultural dimensions and Cha_Beh. Also, a stronger mediation effect is found for Ext_Mot than for Int_Mot because of the stronger regression links both downward and upward of its position in the model. All in all, this supports H.3.2 and partially validates H.3.1.

The respondents’ personal characteristics of income and age have significant relationships with charitable behavior, with more wealthy and older people tending to be more involved in supporting charities on online platforms. On the other hand, gender and education contribute nothing substantial to the model estimated from the complete sample.

To explore potential regional variations in the relationships examined, the PLS-SEM analysis was repeated separately for subsamples based on the respondents’ continent of residence (North America, Europe, South America). This comparative analysis was exploratory, intended to investigate whether the patterns of influence between individual cultural values, motivations, and charitable behavior differed across these broad geographical areas, potentially reflecting different macro-level contexts. It is important to note that this analysis compares respondents residing within these diverse continents, rather than treating the continents themselves as homogenous cultural entities.

By looking at the R-squared values in

Table 4, it is clear that geographically constrained data resulted in more homogeneous response patterns, translating into greater amounts of explained variance in charitable behavior for regional models as compared to the whole sample. The conceptual model describes the South American subsample particularly well, where the coefficient of determination was found to be the greatest (0.476). On the other hand, the number of significant regression weights in the subgroup models is smaller than when the whole sample is used, sometimes despite the values of the regression coefficients being greater. This could be largely explained by the weaker statistical power of the regional models because of a smaller number of observations. The diverse regression patterns in the regional models could be interpreted as follows:

- (1)

The total effect of Cul_Col on Cha_Beh, including the direct effect and mediation, is the strongest in South and North America (0.360 and 0.335, respectively) and the weakest in Europe (0.179).

- (2)

The total effect of Cul_Pow on Cha_Beh is the greatest in Europe and North America (0.257 and 0.223) and the lowest in South America (0.091).

- (3)

The impact of Cul_Unc on Cha_Beh in Europe is almost non-existent (the total effect of Cul_Unc on Cha_Beh is 0.028), while North and South America display similar associative patterns to the complete sample (−0.154 and −0.182).

- (4)

Cul_Pow does not seem to influence external motivations in South America, as compared to the positive impacts observed in Europe and North America.

- (5)

External motivations are the strongest drivers of Cha_Beh in Europe (0.506), followed by South America (0.387) and North America (0.210).

- (6)

The only region where internal motivations played a role in charitable behavior was Europe, where this effect was found to be significant and negative (−0.432).

- (7)

Income has the strongest impact on Cha_Beh in South America (0.330) and the weakest in Europe (0.104).

- (8)

Only in the South American model was education significantly related to Cha_Beh (−0.345), with university degree holders more involved in charitable behavior than those with secondary education.

As an additional analysis, the means of charitable behavior were compared across regions with a one-way ANOVA. The strongest involvement in charitable behavior on online platforms was found in North America (the group mean was 0.169), then in South America (0.150), and in Europe (−0.360). Considering that Cha_Beh was a standardized variable, its mean for the complete sample was 0, and the standard deviation was 1.

The overview of regional differences in regression patterns and levels of charitable behavior presented above clearly validates hypothesis H.4.4.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Theoretical Contributions

The findings of this study offer important theoretical insights by weaving together nuanced perspectives on cultural values, motivations, and social sustainability in the context of charitable crowdfunding. First, they refine the existing body of knowledge on how cultural orientation shapes prosocial engagement. Previous research often relied on country-level scores to highlight the effects of factors such as collectivism or uncertainty avoidance on philanthropic behavior [

18]. In contrast, this study applies individual-level measures of culture [

42,

43] to show that personal orientations can vary greatly within the same nation or region, which, in turn, influences one’s propensity to participate in online fundraising. The results demonstrate that the cultural values revealed by the respondents are indeed associated with stronger or weaker charitable behavior, as well as diverse motivations for charitable giving. It seems that the most important factor is the level of collectivism that a person adheres to, with more collectively minded respondents showing stronger support for online charities, both in terms of past involvement and future plans. This is consistent with the results of other studies, according to which collectivism is a good predictor of charitable donations, for example, [

87]. Collectivism was also linked to higher levels of both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations for charity. The second investigated cultural dimension, uncertainty avoidance, was correlated positively with both extrinsic and intrinsic motivations, but its overall effects on charity behavior were negative, except in Europe, where it was neutral. This aligns with previous research, which suggests that lower uncertainty avoidance strengthens crowdfunding activities [

18]. The relationship between power distance and charitable giving was more nuanced because of the way that this construct moderated the correlation between internal motivations and charitable behavior. Our data implied that high levels of power distance made the influence of intrinsic motives on an individual’s support for charities more negative, but low levels of declared power distance could turn internal motivations into a positive driver of charitable action. When this interaction effect was combined with direct and moderated regression pathways, the overall influence of power distance shifted from negative to positive, depending on the context. Furthermore, this interaction effect demonstrated scenarios in which internal motivations, which have no significant relationship in general, could have either a positive or negative impact on charitable behavior. As indicated by Winterich and Zhang [

81], higher power distance tends to be associated with decreased charitable behavior. However, various factors may mediate or moderate this relationship. For example, internal motivation stemming from perceived responsibility may help overcome the negative influence of power distance on charitable actions. Furthermore, Siemens et al. [

45] found that consumers from “tight” cultures (which can be associated, inter alia, with higher power distance), when donating, are influenced by internal motivations related to norm adherence.

Our data further reveal how self-determination and volunteer-function perspectives on motivation [

59,

62] can be usefully applied to charitable crowdfunding. Contrary to the widespread assumption that intrinsic or altruistic motives are always the key drivers of prosocial behavior [

88], extrinsic motives, such as social recognition, reciprocity, and public image, tend to provide more robust support for donation intentions. As it was already mentioned, the intersection of cultural context and these motivations yields surprising outcomes, including scenarios in which high power distance can negate the effect of otherwise strong intrinsic drives. Such patterns align with emerging views that motivational forces are heavily shaped by contextual and cultural variables [

77], rather than being uniformly applicable across diverse populations. This study, therefore, contributes to a more refined understanding of how extrinsic and intrinsic motivations jointly function in digital fundraising while also explaining why certain motivations can be more salient in specific cultural environments.

Our cross-regional comparison showed that among European respondents, strong internal motivations tended to lower a person’s engagement with digital charitable platforms. It seems then that participation in online fundraisers contributing to worthy causes is, for many people, just an image-building opportunity. The impact of external motivations on charitable behavior is consistently positive across regions, but it varies in strength, with North America showing the weakest relationship and Europe the strongest one. The observed regional differences could be attributed to diverse ways of organizing social security systems. For example, the United States is characterized by a well-developed third sector, with NGOs assisting needy people in a manner similar to the government and the public sector in the European Union. Consequently, respondents living in countries with strong NGO sectors performing social services might find it natural and necessary to share some of their incomes with charities. And because, according to our data, charitable behavior is more common in such countries, the external incentives for charitable giving could be less potent, as there is arguably less to gain in terms of personal image improvements if a behavior is commonplace. On the other hand, in Europe, the widespread view may be that it is the government’s responsibility to use some tax money to support those in need. The belief that state-funded programs are an adequate solution to social problems could make people with strong internal motives for charity avoid organized, large-scale initiatives and instead opt for more direct support for those in need, not necessarily through money donations, but also with other, more personalized forms of help. However, those Europeans who decide to donate on online platforms might be driven not so much by the conviction that such a donation is necessary but by the hope that it will be noticed by friends and acquaintances and provide a boost to their personal image.

Our analysis included gender, age, education, and income as control variables to account for potential demographic influences. Notably, income and age showed significant positive associations with charitable behavior in the full sample, aligning with previous research suggesting greater capacity or propensity for giving among wealthier and older individuals [

78,

80]. Gender and education did not show significant effects overall in this study, though regional variations were observed. Controlling for these factors provides greater confidence in the observed relationships between cultural values, motivations, and charitable behavior.

Finally, by situating these cultural and motivational factors within broader sustainability discourse, this research clarifies the theoretical underpinnings of how crowdfunding platforms facilitate socially sustainable outcomes. Social sustainability involves collective actions that promote equity, community well-being, and resilience [

10,

13], but such efforts depend heavily on participants’ cultural mindsets and motivational drivers. The results suggest that collectivist norms amplify readiness to share resources through online means, while strong extrinsic motivations can broaden donor pools and potentially stabilize giving in times of economic or social uncertainty. Designing or regulating digital platforms in ways that resonate with specific cultural orientations, such as highlighting the reputational benefits of donation in more power-distant societies or reducing perceived risks for high uncertainty-avoidant users, can bolster prosocial participation. By showing that social sustainability imperatives—like inclusivity and communal responsibility—are closely intertwined with the cultural and motivational fabrics of individual donors, this study advances a theoretical approach that integrates insights from psychology, marketing, and international business into the field of digital philanthropy.

7.2. Practical Implications and Recommendations

The findings of this study have several practical implications for organizations and stakeholders seeking to enhance charitable giving via crowdfunding platforms. One key insight is that fundraising strategies should be culturally sensitive. Because individual cultural values differ even within the same country or region, platform developers and nonprofit managers can benefit from gathering preliminary data on donors’ cultural orientations. This may involve short pre-campaign surveys or simple profile questionnaires that gauge whether participants lean more strongly toward collectivism, how comfortable they are with uncertainty, or the degree to which social hierarchies matter to them. By aligning digital appeals and messaging with these cultural orientations, platform operators can better match donors’ motivations and thus improve donation intentions. For instance, platforms targeting audiences where collectivist values are prevalent (

H1.1,

H.3.1) could enhance engagement by emphasizing community impact metrics, showcasing collective achievements, and facilitating team-based donations. A relevant example is a successful fundraising campaign by the Ocean Cleanup for removing plastics from waters [

89], which emphasized a shared goal by showing how donations contribute to a larger purpose, such as life improvement in a broader community, while highlighting bonding social relationships. Specifically, the narrative in the campaign showcased collective responsibility for the environment and highlighted the broader goal of cleaning oceans to restore marine life for future generations.

Conversely, for users high with uncertainty avoidance (H1.3, H.3.1), which was negatively associated with charitable behavior overall, platforms should prioritize transparency and risk reduction. This includes providing detailed project updates, clear financial reporting on fund usage, visible security badges, and endorsements from trusted institutions to mitigate perceived ambiguity. Furthermore, the complex role of power distance (H1.2, H.3.1), particularly its interaction with intrinsic motivation, suggests that in contexts where power distance values are high, platforms might benefit from offering tiered recognition systems or highlighting endorsements from influential figures, framing donation as a socially recognized and esteemed activity.

The strong link between extrinsic motivations and donation behavior underscores the importance of visibility and social recognition in digital campaigns. Fundraising platforms can design interactive features—such as donor leaderboards, social sharing tools, or digital badges—that validate contributors in ways that visibly honor their generosity. Such public acknowledgement works particularly well in communities where social standing is highlighted and can also attract new donors who perceive it as a rewarding social experience. For instance, the Polish crowdfunding platform Zrzutka.pl offers donors the option to be publicly identified with specific campaigns if they choose. Care should be taken, however, to ensure that these recognition-focused strategies do not inadvertently discourage potential givers with high intrinsic motives, who may prefer quieter, more personal engagements. A careful balance can be achieved by offering optional anonymity settings or thanking donors individually, letting them decide whether to have their contributions displayed publicly.

Another important practical implication is that uncertainty avoidance can reduce donors’ willingness to contribute. Some individuals are hesitant to give if they perceive risks, lack of transparency, or ambiguity in how the funds are used. Thus, risk-averse individuals require greater confidence, for example, in a crowdfunding platform’s security and transparency, before making online donations. Platform operators can assuage such concerns by providing detailed, credible information about project goals, the intended beneficiaries, and the mechanisms for fund distribution. GoFundMe exemplifies this approach by providing detailed descriptions of campaign purposes, allowing real-time donation tracking, posting frequent updates, and offering donor protection (i.e., refunds) in case of fraud. Regular updates and transparent reporting create a sense of security, which is especially critical for high-uncertainty-avoidant donors. In addition, for target populations that place a premium on trust—be they in Europe or elsewhere—partnering with reputable institutions or well-known organizations can help signal reliability. Such collaborations often lead to higher conversion rates since donors see them as a way to mitigate perceived risks of misuse or non-fulfillment.

A further implication concerns the interplay between intrinsic motivation and power distance, which suggests that certain campaigns may flourish in low power-distance communities where altruistic impulses can be nurtured more openly. In contrast, charities operating in societies or social circles characterized by high power distance might need to adapt their content to highlight any prestige or reputational gains that may be accrued to donors. For example, “elite donor” acknowledgements, personalized thank you notes from influential community leaders, or exclusive events for top contributors can bolster the sense that giving is both personally meaningful and socially recognized. Although such approaches may appear to place emphasis on status, they can still advance social welfare goals if they bring much-needed resources to beneficiaries.

Finally, this study’s emphasis on social sustainability situates charitable crowdfunding within a broader movement to address equity and inclusion. Policymakers and NGOs should note that digital fundraising campaigns have the capacity to engage diverse segments of the population, but they will be more effective if they dovetail with donors’ broader cultural perspectives and motivational profiles. Public administrators can assist by creating guidelines or incentives for organizations to incorporate local cultural values into their philanthropic strategies. Such support might include education campaigns that explain how donation-based crowdfunding supports community development goals or matching grants that encourage more hesitant donors to contribute. By giving appropriate attention to both the technological and social dimensions of crowdfunding, and by designing campaigns that resonate with individuals’ cultural mindsets and motives, charitable organizations, platform developers, and government agencies can improve not only the immediate efficacy of their fundraising efforts but also their long-term contributions to social equity and communal resilience.

8. Limitations and Directions for Further Research

It is important to acknowledge the limitations inherent in our study design. Firstly, the use of a cross-sectional survey design prevents the establishment of definitive causal relationships between cultural values, motivations, and charitable behavior. The associations observed indicate correlations, but the direction of causality cannot be confirmed. Longitudinal studies tracking individuals over time, or experimental designs manipulating specific variables, would be necessary to provide stronger causal evidence.

Additionally, the use of MTurk as a data collection platform may introduce limitations related to sample representativeness. Specifically, MTurk samples often overrepresent individuals who are more digitally literate and comfortable with online tasks. Furthermore, MTurk workers often include individuals from lower to middle-income brackets and may not represent the full range of potential donors across different cultural and economic segments. Despite these limitations, MTurk remains a valid data collection platform for accessing diverse and culturally varied participants, especially when coupled with screening measures and attention checks, which we implemented to ensure data quality. Nonetheless, future research should aim to validate these findings through alternative sampling methods, such as nationally representative surveys.

Furthermore, the regional comparisons relied on broad continental groupings (North America, Europe, South America). While revealing some interesting differences, these findings must be interpreted with caution, as significant cultural diversity exists within each continent. Treating these large geographical areas as units of analysis is a simplification. Future research employing larger samples could allow for comparisons across more granular units, such as specific countries or culturally distinct regions within continents (e.g., comparing Western vs. Eastern Europe), potentially yielding more nuanced insights.

In addition, the operationalization of charitable behavior (Cha_Beh) combined measures of past behavior (donation amount/frequency) with future donation intention. While intended to capture overall engagement propensity, this aggregation might mask potential differences between predictors of past actions versus future intentions. Future research could separate actual giving from planned contributions or incorporate real-time metrics, such as donations tracked directly through a crowdfunding platform. This approach would help clarify whether intention consistently translates into action, especially in contexts where uncertainty avoidance and power distance may moderate one’s willingness to follow through on donation plans.

The results also point to promising avenues for deepening theoretical inquiry. While this work focused on individual cultural values, additional factors, such as religiosity, political ideology, or institutional trust, may complement or interact with cultural dimensions in driving philanthropic engagement. Incorporating these variables into a more elaborate model could yield fresh insights into why certain motivations resonate in one context while remaining inconsequential in another. Similarly, the differential roles of extrinsic and intrinsic motivations across regions suggest a need for more granular typologies of motivation. Future studies could explore whether specific sub-facets of intrinsic motivation, such as empathy or moral obligation, are more sensitive to variations in uncertainty avoidance or power distance than others.