1. Introduction

Geographical indication (GI) law has emerged as a powerful tool for the promotion of economic development, preserving cultural heritage, and enhancing market competitiveness for GIs unique products. The concept of GI is rooted in the connection between a product’s qualities and its place of origin; GIs ensure that communities benefit from their traditional knowledge, skills, and natural resources [

1]. GIs also serve as a pathway for sustainable economic growth by enabling small-scale producers to access niche markets and secure premium prices [

2]. The objective of GI as a law is not limited to protecting the unique quality and identity of products but also aims to uplift the economic conditions of contributing individuals [

3]. There is a strong connection between the products and their place of origin that significantly influences international trade [

4]. A product’s reputation extends beyond its geographical origin, as seen by the fact that there has always been a strong demand for products originating from a specific location with a well-established reputation [

5]. The superior quality of a product can be associated with a specific geographical region and is believed to be distinct due to factors such as water, climate, soil, craftsmanship, or specific skills [

6]. These unique geographical conditions drive consumer demand for such products. For example ‘Champagne’ belongs to Champagne, a wine region of France and it is known worldwide as per its GI. Similarly, “Cheddar Cheese” historically derives from the village of Cheddar in the south of England, indicating its geographical origin.

In Pakistan, “Peshawari Chappal”, a handmade shoe, originates from the city of Peshawar and reflects the country’s unique geographical and cultural heritage [

7]. Similarly, “Sindhri Mangoes” are associated with the province of Sindh, representing the origin and cultivation of this mango variety [

8]. Other notable GI products include Basmati rice and the citrus fruit known as Kinnow. However, to date, Pakistan has 10 registered GIs (see

Table 1) and 65 notified GIs, indicating that many notified GIs remain unclaimed by local stakeholders and are only listed in government registers. This situation largely stems from ineffective legislation governing GIs in Pakistan. Until recently, the absence of a dedicated legal framework resulted in the loss of GI protections as intellectual property rights. The enactment of the Geographical Indications (Registration and Protection) Act 2020 (GI Act) marked significant progress; however, the Act still lacks sufficient provisions to protect GIs as community-owned assets.

While the GI Act provides a legal foundation to protect and promote GIs, unauthorized use of product entitlements continues to negatively affect the economy. Gaps in the existing legal framework, implementation challenges, weak enforcement, and limited stakeholder awareness continue to hinder the realization of GIs’ full potential. As a developing country rich in agriculture and handicrafts, Pakistan is uniquely positioned to leverage its GIs for socio-economic development. As per a report by the Pakistan Stock Exchange, agriculture is the backbone of the country’s economy, which contributes 24% to GDP and employs 37.4% of the workforce [

9]. Similarly, the handicraft sector employs approximately 13.7% (PSE 2024) of the country’s workforce, which is an essential component of livelihoods, particularly in rural areas [

10].

Given Pakistan’s strategic position along key international trade routes, including the historic Silk Road, and its rich portfolio of GI-worthy products, the development of a robust legal framework for GIs is crucial. A comprehensive approach to GI protection could protect local products and serve as a model for other developing states facing similar challenges. Before the enactment of the GI Act 2020, GI protection in Pakistan primarily focused on alignment with Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) implementation [

11]. The economic significance of GIs highlights institutional challenges and progress toward establishing a “sui generis” legal framework [

12].

The current study employs a doctrinal and comparative methodology to examine the alignment of Pakistan’s GI framework with the more developed system of the European Union (EU). This approach is led by the primary goals of international GI protection frameworks as set by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), particularly the Lisbon Agreement for the Protection of Appellations of Origin and their International Registration and TRIPS [

13].

This study focuses on three core parameters to assess the effectiveness and limitations of Pakistan’s GI framework in comparison to the international standards.

- (i)

Applicability: This parameter evaluates the scope and relevance of the GI Act 2020 in addressing the legal needs of Pakistan’s agricultural and handicraft sectors. It examines whether the provisions in the Act adequately cover the diverse range of GI products and whether the framework can be applied consistently across different sectors and geographical regions. By comparing the applicability of Pakistan’s GI framework with the EU, the study identifies the extent to which the current legal provisions can cater to the needs of local producers while ensuring the protection of their products in both domestic and international markets.

- (ii)

Enforceability: This parameter examines the practical aspects of enforcing GI protections under Pakistan’s legal system. It scrutinizes the existing enforcement mechanisms and compares them to the more robust systems in place within the EU, focusing on aspects such as administrative processes, legal remedies, and the role of regulatory bodies. By analyzing the enforceability of GI rights in Pakistan, this study highlights key barriers, such as weak coordination between IP tribunals and businesses and delays in registration processes, which hinder the effective protection of GIs. A key aim is to propose enhancements that would align enforcement practices with international standards.

- (iii)

Compatibility: This parameter assesses the degree to which Pakistan’s GI Act 2020 aligns with international frameworks, particularly WIPO guidelines and EU regulations. Compatibility is crucial for ensuring that Pakistan’s GI system can be recognized and integrated into the international system, providing local producers with access to global markets. This study critically analyzes the legal gaps and deficiencies in the GI Act, particularly in terms of international registration mechanisms, as exemplified by the Lisbon Agreement. The focus is on identifying the legal inconsistencies that prevent Pakistan from fully benefiting from the international recognition of its GI products.

This study further aims to provide comprehensive insights into the legal reforms necessary for Pakistan to establish a more effective GIs protection system. By aligning the national framework with international best practices, this study seeks to promote the economic, cultural, and social benefits of GIs, while enhancing Pakistan’s ability to compete in international markets, ultimately contributing to sustainable development in the country.

2. Geographical Indications Act 2020 of Pakistan and Its Implications on the Economic System

GIs in Pakistan serve as a significant public policy tool for economic advancement and sustaining the livelihoods of skilled workers and farmers, especially as Pakistan’s economy is primarily based on agriculture, traditional knowledge, and the handicrafts sector [

14]. GIs hold significant potential to enhance rural incomes and stimulate wider-based rural advancement, as seen by EU policies results [

15]. As an emerging economy, Pakistan’s growth is largely driven by agriculture sector, contributing 6.25% growth in the fiscal year 2024. More than 42% of the country’s merchandise exports are earned via the agriculture sector. The GDP reached PKR 106,045 billion (approximately USD 375 billion), marking a 26.4% increase over the previous year’s GDP [

16].

The importance of agriculture in Pakistan’s growth is reflected in its foreign exchange earnings, nutritional contributions, and its role in providing of raw materials to the local industries. For instance, in 2024, Pakistan exported a record 900,000 metric tons of Basmati, which contribute significantly to the country’s economy [

17]. Similarly, the mango sector plays a pivotal role in the country’s horticulture; mango exports generated USD 46.7 million since mid-July 2024, exporting 13,681 metric tons to 42 countries.

Sindhri mango is one of best well-known GI products from Pakistan, which made approx. USD 13.2 million revenue from the United Kingdom alone; the UK is followed by significant contributions from the UAE at USD 9.2 million and Kazakhstan at USD 8.95 million, among other countries. With an annual production of approximately 1.8 million tons, mostly from Sindh and Punjab, mangoes are among Pakistan’s tops agriculture exports. Additionally, Pakistan’s textile exports reached USD 15.97 billion, marking an increase of USD 1.3 billion from previous year (PSE, 2024).

There has been a notable increase in the international demand for agriculture, textile, and handicrafts from Pakistan. Therefore, it is crucial for the government to protect the skills, specialized craftsmanship, and economic contributions of artisans and skilled individuals associated with specific geographical products. Pakistan has registered products in the following six categories: agriculture, manufactured goods, handicrafts, food stuff, textiles, and minerals [

18].

Figure 1 illustrates the percentage contribution of each GI category to the total registered in Pakistan.

Figure 1 highlights sector-wise contribution of several industries, Agriculture leads with 39%, followed by handicrafts at 25%, food stuff at 15%, and minerals and mines at 12%, while textiles and manufactured goods contribute 6% and 3%, respectively. The dominance of agriculture and handicrafts reflects their economic and cultural significance. However, the lower shares of textiles and manufactured goods indicate the potential growth opportunities. This breakdown provides insights for the policymakers to enrich underrepresented sectors through targeted interventions like GI protections.

The GI Act of 2020 marks a significant step towards the protection of commercial integrity. The GI Act ensures the maintenance of the high quality of such goods by introducing a label system for authentic products made by the original producer. Whether it involves protecting local artisan’s craftsmanship, venerable traditional practices passed down from generation to generation, or any other form of indigenous knowledge, these initiatives aim to promote and protect the region’s economic and cultural heritage. However, from enactment until now, only 10 [

19] GIs have been registered with the GI Registry of Pakistan since 2021, and the GI Registry has notified only 65 GIs [

20], a relatively small number in comparison with its neighbor country, India, which has a total of 643 registered GIs to date [

21].

Registered and Notified GIs in Pakistan Under the GI Act 2020 and Its Legal Implications

The difference between registered and notified GIs is significant in the prospect of legal protection granted to such products. Registered GIs are products that have gone through a proper application procedure and have been granted legal protection by the Intellectual Property Organization of Pakistan. Registered GIs enjoy full legal status, ensuring that only authorized users with a GI registry can use GI products, thus preventing unauthorized use or misrepresentation by non-local producers. Notified GIs, on the other hand, are such products publicly announced by the government which indicates their intent to seek protection based on their unique geographical origin. However, the notified GIs have not gone through the formal process of registration, meaning they lack the full legal protection associated with registered GIs.

The notified GIs serve as a preliminary step, where the stakeholders can verify and review the product’s claims before the products move toward the complete registration stage. The key difference between the two lies in the legal status, with the registered GIs gaining complete protection under the law while the notified GIs are at an early stage and may not have a legal restriction on use. These provisions represent Pakistan’s efforts to protect regional products from misappropriation, ensuring their recognition in local and international markets.

Table 2 highlights the registered and notified GIs from each province [

22].

It can be clearly observed from the table that the northeastern region of Pakistan, particularly Punjab, demonstrates significant potential for GIs compared to other provinces. Punjab leads with 4 registered GIs and 27 notified GIs, the highest among all provinces, reflecting strong engagement in the GI registration and notification process. Sindh also shows commendable progress, with an active approach toward GI registration and notification. In contrast, the northern and western regions of the country, such as Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Baluchistan, exhibit minimal activity in GI registration and notification. The limited number of GIs originating from such areas can be attributed to a lack of awareness and inadequate mechanisms for protecting region-specific goods and products. This highlights the need for targeted initiatives to raise awareness and support GI protection in such underrepresented provinces. Pakistan’s economy relies on agriculture and products with GI potential. Raising awareness about GIs is crucial to unlock the full potential of these products.

3. Challenges to the Sustainable Economy of Pakistan Due to GI Issues

The first GI of Pakistan was “Basmati Rice”, registered in 2021. It is famous globally for its long, slender grains, aromatic fragrance, and delicate taste [

23]. As a result, the Trade Development Authority of Pakistan applied for its registration and logo, which were officially registered under class 30 of the GI Act 2020 [

24]. As already discussed, Pakistan is an agricultural-based economy, and since its independence the country has been striving toward development [

25]. This milestone marked a significant step in the protection of Pakistan’s indigenous products in the international markets, which can potentially enhance exports and foster rural development. However, such achievement also reveals several underlying challenges which threaten the sustainable economic benefits of GIs in Pakistan. According to a report, numerous GIs exist in every province of the country. Pakistan’s diverse cultural heritage and strong regional identities further enrich its potential for GI protection [

26]. However, the GI Act 2020 suffers from significant gaps in its legal framework, implementation, enforcement, and stakeholder awareness which hinder the realization of its full potential.

3.1. Ineffective Implementation of the GI Legal Framework in Pakistan

One of most prominent legal challenges is the lack of ownership clarity and benefit-sharing mechanisms. In various cases, GI products are produced across multiple regions but the law does not adequately address how economic benefits are distributed among stakeholders, creating confusion and discouraging producers from seeking registration. From an implementation perspective, the registration process is perceived as lengthy, complex, and burdensome. A significant number of participants in a study acknowledged that obtaining GI registration involves numerous formalities, such as form filling, signatures, verification procedures, and additional authorization time, all of which are time-consuming [

27]. This bureaucratic complexity creates obstacles for small-scale producers and artisans, who often lack the resources or expertise to navigate the process. The absence of streamlined registration mechanisms further delays GI recognition and limits its economic benefits.

3.2. Enforcement Gaps and Misuse of GIs

The lack of enforcement mechanisms to protect its registered GIs from counterfeiting and misuse in both domestic and international markets is another issue. Inadequate monitoring systems and weak penalties allow unauthorized use of GI-protected names, which diminishes their market competitiveness and value [

28]. For instance, even after the registration of Basmati Rice, disputes over its authenticity and misuse in export markets persist. This weak enforcement diminishes the Pakistani GIs value and undermines consumer confidence in their authenticity and quality [

29].

3.3. Legal Awareness of GIs and Sustainability

Lack of awareness between stakeholders remains a major challenge. Many local producers and artisans remain unaware of the benefits of GI registration or the process involved. The absence of targeted outreach programs to educate stakeholders about the culture and economic importance of GIs has further limited participation in the registration process. Without sufficient awareness, potential GI products remain unregistered, leaving them vulnerable to misappropriation [

30].

4. Eligibility Criteria for Registering GIs

The GI registration process in Pakistan is governed by the GI Act 2020. As per Section 6 of the GI Act, a centralized GI register must be maintained, containing the details of registrants and the authorized users. The register contains two parts, Part A for the registrants and Part B for the authorized users. It is open for public inspection to ensure transparency. Section 7 of the Act mandates that GIs be classified according to the international classification of goods, while Section 8 imposes restrictions on the types of GIs that may cause confusion or be misleading.

The registration procedure begins with an application under Section 12, which requires detailed information including the book of specifications. Section 15 explains the application examination by the Registrar. Section 11 introduces the centralized ownership model, where federal government retains the exclusive ownership over all GIs. Local producers, cooperatives, and artisans can be only registered as authorized users, which limits the ability to protect and control the GIs which they produce. This centralized structure restricts grassroots participation, which undermines the core aim of empowering the local producer and limiting the economic potential of GIs [

31].

These provisions allow the federal government to delegate the application rights for GI registration to public bodies, statutory bodies, provincial administrations, or any other government organization with legal standing and responsible for covering GIs within Pakistan’s territory. However, this practice stands in contrast with the universal goal of GI registration, which aims to empower the grassroots and local producers. This approach deviates from international best practices, such as those established by the EU [

32]. In addition, its neighbor country India also delegates its GI rights to farmers and local associations. By entrusting ownership to such groups, Pakistan will ensure the equitable distribution of benefits and strengthen local economies. Pakistan’s sui generis GI Act not only challenges the TRIPS spirit but also fails to unlock the potential of GIs to contribute to sustainable rural development [

33]. Instead of being the GIs proprietor, the government sector should play a role as a facilitator or mediator in the GI registration process. Notably, Section 6(5) of the GI Act specifies and governs Part B registration.

This study observed that a very small number of applications have been registered in Parts A and B. As per the GI office, only 49 applications have been filed in Part B as of January 2024. Notably, only a single application for Part B has been filed specifically for Basmati rice under class 30 [

33]. This indicates a significant gap in participation by local producers across other registered GIs in Part B. Despite the potential cultural and economic value of such registrations, local producers appear to be unaware or unable to access the associated benefit, which severely limits the overall impact of GI protection. There is no maximum limit on applications in Part B. However, the absence of tangible financial benefits discourages producers from registering as beneficiaries. Neither the GI Act nor other related policies offer a clear mechanism for benefit-sharing among the producer communities. Due to the lack of financial benefits, many producers do not see value in registration under Part B.

The following factors can also contribute to limited participation in Part B registration:

- (i)

Lack of awareness: Producers and artisans are often unaware of Part B registration, or its potential incentives;

- (ii)

Unfamiliarity with the registration process: Many potential beneficiaries are unaware of the registration procedure;

- (iii)

Lack of technical expertise: Small-scale producers often lack the technical knowledge or resources to complete the registration process effectively.

To address such challenges, IPO Pakistan should take the initiative to raise awareness about Part B registration, its benefits, and the administrative setup for sharing benefits, which could encourage more beneficiaries to participate and strengthen the impact of GI protections. Simplifying the registration process and providing a step-by-step guide in local languages would further help to overcome the barrier of unfamiliarity.

5. Potential of GIs for Pakistan’s Sustainable Economy

Despite institutional limitations, GIs hold immense potential for advancing Pakistan’s sustainable development goals. They serve as powerful public policy tools for promoting sustainable rural development, preserving cultural heritage, and increasing market competitiveness. As per the Ministry of Commerce report, the Pakistani GIs sector generates billions of dollars in trade annually. For instance, rice exports alone are valued at USD 3.8 billion [

34]. Pakistan also exports millions of dollars’ worth of Kinnows and mangoes [

35]. Additionally, Pakistan’s industries are rich in medical equipment, sports gadgets, and textiles. The textile industry, in particular, produces denim products for Western markets, thereby increasing the nation’s export earnings [

36].

From an agricultural perspective, rice stands out as the second key commodity after wheat [

37]. Most farmers and their families rely solely on rice as their primary source of income, making it a crucial component that could significantly contribute to the country’s GDP growth. Promoting GI-protected products such as rice and traditional crafts could significantly contribute to economic development [

38].

Despite the potential for hundreds of GIs, only a limited number have been officially registered. Delay in registration and lack of effective institutional support caused Pakistan to forfeit a significant portion of its economic gains [

39]. By simplifying the process of registration, introducing user-friendly mechanisms, and enhancing its enforcement measures, Pakistan can unlock the full potential of its GI assets.

5.1. Aligning the GI Act of Pakistan with International Best Practice: A Comparative Prospect

Pakistan is a common-law country and has adopted many laws from the EU. To unlock the potential of GI development, Pakistan’s GI framework must harmonize with international standards, such as the European Union’s robust GI protection system. The EU GI system enshrined under Regulation No. 1151/2012 is widely regarded as a benchmark for guaranteeing product authenticity, export competitiveness, and producer protection [

40]. Aligning Pakistan’s GI law with EU standards would enhance the international recognition of its indigenous products and strengthen its domestic rural economy [

41].

The EU has established a decentralized and multi-layered GI system which empowers local associations and producer groups as the managers and legal owners of their GIs. This practice not only ensures strong legal participation but also encourages the creation of consortia responsible for drafting specifications, managing certification, conducting quality control, and its branding. Notably, third-party inspections ensure compliance, while the EU commission coordinates oversight, dispute resolution, and cross-border protection of GIs under Free Trade Agreement (FTAs) and the TRIPS regime. In contrast, Pakistan’s GI regime under the GI Act 2020 is centralized to the federal government, which acts as a sole proprietor. The producer and grassroots producer can only be registered as an “authorize users” in Part B, with no legal claim to GIs, which effectively excludes grassroots producers and cooperatives from benefit-sharing.

Beyond the legal ownership, several operational gaps arise. The EU mandates rigorous quality assurance through designated inspection agencies, while Pakistan lacks a sustained monitoring mechanism. The GI Act 2020 mentions registration inspection, but the Act is silent on post-registration quality checkup or any mechanism which can verify its authenticity at a market level. Additionally, Pakistan’s process pertaining registration remains bureaucratic and inaccessible to most local producers. In the EU, the GI registration process is widely understood and accessible by SMEs and farmers due to institutional training programs and awareness campaigns, while in Pakistan, stakeholder awareness is limited and fragmented [

42].

The EU model also incorporates the benefit-sharing mechanisms through market linkages, cooperatives, and premium prices, which provide direct financial incentives to its producers. Due to lack of any formal benefit-sharing mechanism, exporters, traders, or intermediary agencies often capture the financial gains. This undermines both the economic logic of GI protection as well as its role in rural development.

In addition to the operational capacity and institutional structure, critical distinction lies in the enforcement authority and legal standing which is granted to producers within the two frameworks. In the EU, the GI owner groups are recognized as autonomous right holders which have the legal right to take any legal action against its misuse or any infringement in the EU and internationally, which enable swift and direct enforcement of the GI rights of the affected holders. On the other hand, in Pakistan’s GI Act 2020 the federal government has exclusive right of ownership, which creates a reliance on state institutions which often lack responsiveness. Additionally, while EU GIs benefit from the automatic protections via FTAs and mutual recognition agreements with other jurisdictions, Pakistan’s GI system lacks such global agreements which exposes its producers to a heightened risk of misappropriation and market-exclusion abroad. Such limitations highlight that Pakistan needs to amend its GI law urgently, empower its local producers legally, and pursue GI international agreements to align more closely with international best practices.

5.2. Short-Term and Long-Term Benefits of GIs Protection

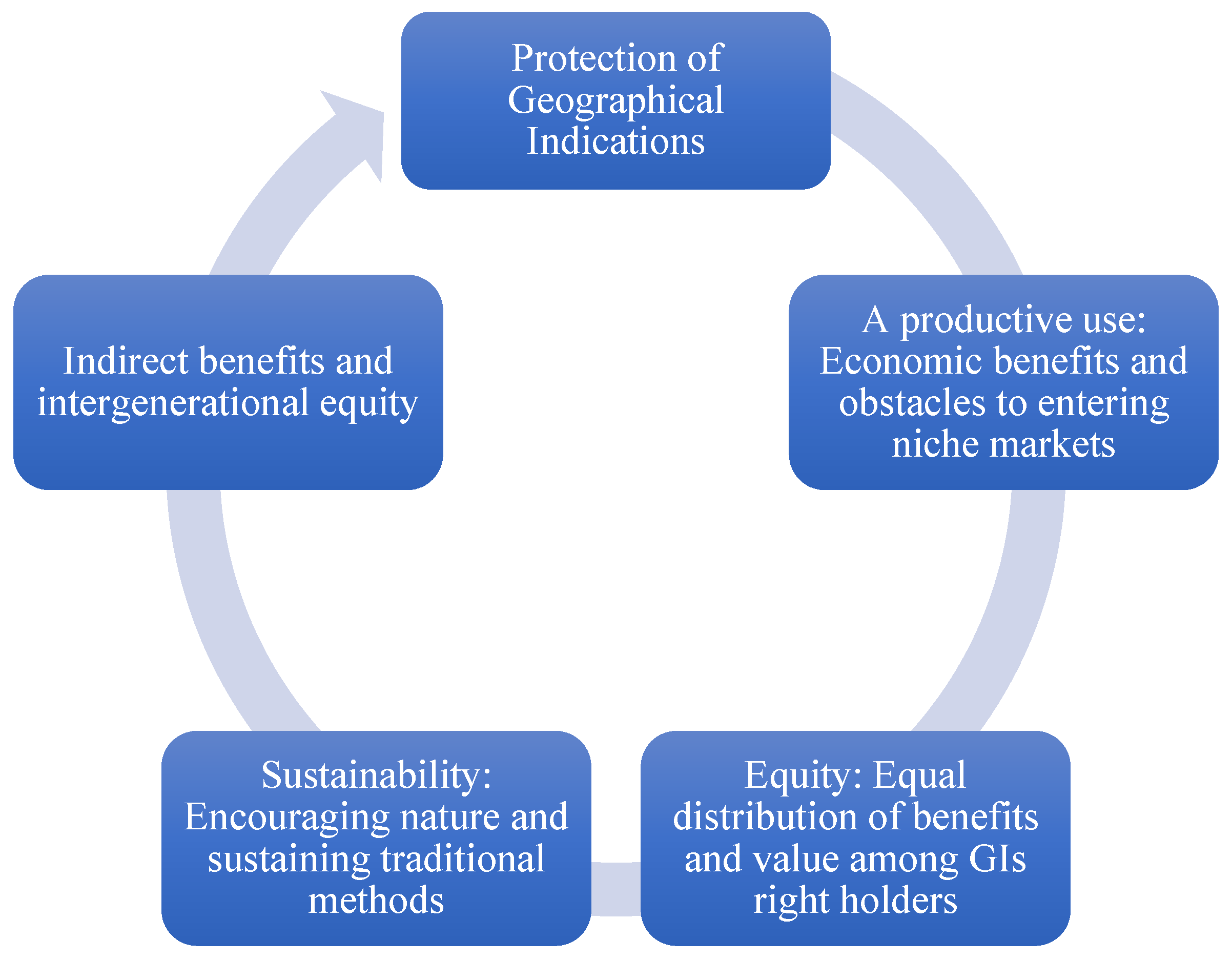

In the short term, addressing such challenges can boost exports and the production of GI-protected products; over the long-term, this would lead to rural sustainable development, poverty reduction, and enhance global competitiveness. This study identifies the need to focus on raising awareness, building institutional capacity, and introducing a transparent, simplified process to ensure the effective implementation of GI protection in Pakistan (See

Figure 2).

Figure 2 illustrates the long-term benefits of GIs, explaining how GIs contribute to sustaining social, economic, and cultural growth over time. The benefits include increased market competitiveness for GI-protected products, which enhances income for local producers and preserves the cultural heritage. Moreover, GIs promote environmentally sustainable practices and rural development by supporting region-specific goods. The data in the figure, derived from the author’s work, highlights that GIs not only support the short-term gains, such as improved exports, but also provide enduring value by developing communal empowerment, ensuring equitable economic benefits, and protecting traditional knowledge. This emphasizes the transformative potential of a well-implemented GI system for the socio-economic and cultural advancement of Pakistan.

5.3. Enhancing the GI Registration Process and Accessibility for Applicants: Moving Towards Sustainable Economic Growth

Pakistan is taking significant steps to protect its commercial products and uphold their high quality by implementing a labeling system that authenticates goods from their original producers. The government started the initiative in 2021 to protect the people’s interests by obtaining GI tags. Under the current framework, any public body, statutory body, provincial administration, government organization, or government enterprise in Pakistan can register a GI. The IPO is fully responsible for managing the application and protecting the collective interest of producers.

However, a significant flaw in Pakistan’s GI law is that it restricts GI ownership rights to government bodies, thereby limiting the role of local producer associations and farmer’s groups. This restriction diminishes the economic and decision-making power of the actual artisans and producers who create and maintain the GI product’s uniqueness. Studies on GI economics demonstrate that when GIs are owned and managed by a local producer association or farmer group they generate greater incomes, increase market access, and strengthen local economies. For Pakistan’s GI framework to become more effective, it should align with international best practices, such as the EU [

43]. The EU empowers local producers and allows them to own and control GIs to enable them to reap direct economic benefits from their registration. Currently, under Pakistan’s GI Act 2020, the general public can access GIs as an authorized user after registering with the GI Registry. Shifting GIs ownership and control to local producer associations would ensure greater inclusivity, economic empowerment, and transparency.

Section 12 of the GI Act 2020 outlines the procedural requirement of GIs in Pakistan. The application should consist of comprehensive details which clearly define the product’s unique character, the applicant’s details, the class of goods, a book of specifications that contains the standard and specification of the product, and a payment receipt for the prescribed fee. A certified map delineating the area associated with the GIs must accompany it.

Once submitted, the GI Registrar reviews the application to certify compliance with these requirements. If any deficiencies are identified then the Registrar may request the additional information or clarification from the applicant. In cases where the review process needs specialized expertise, the Registrar has discretion to seek assistance from experts in the relevant field. If the GI Registrar approves the application, the product is officially registered, a GI logo is issued, and the decision is communicated to the applicant, who is recognized as an authorized user for the GI. However, if the application is rejected, the decision can be challenged via appeal to the relevant IP tribunal [

44].

5.4. GI Products Marketing and Sustainable Economic Growth

The rise in GI products has led to quality issues due to the presence of counterfeit products in the market, limiting consumer accessibility to genuine products [

45]. Pakistan has established a regulatory framework for registered GIs under Section 24 of the GI Act 2020, which mandates support for product producers in marketing and promotion. However, practical implementation remains absent. Every GI product has sales potential, which immensely benefits its original producer [

46]. Proper marketing and branding strategies are essential to reduce the risk of product failure and to generate handsome revenue for all stakeholders in the value chain [

47]. The most suitable and recent example of GIs in Pakistan is the “Basmati Rice logo”, which represents a significant step; however, most of the other products registered as GIs lack logos or visible branding efforts. Developing countries with similar economic profiles are far more actively promoting their products in the global market. A market survey reveals that although several rice brands are available in the market, none effectively utilize the GIs logos to authenticate their products [

48,

49]. Furthermore, there is no robust mechanism in place to verify whether these brands are selling the original products or misleading the public about their origins. Effective GI product marketing must integrate social, cultural, and economic aspects. Quality control and authenticity are crucial to maintaining consumer trust and ensuring market competitiveness. The absence of a centralized verification and monitoring mechanism represents a significant shortcoming in Pakistan’s GI system.

Pakistan comes with policy guidelines for the implementation of such an act, but the state is losing an opportunity in the international market to show Pakistan’s GIs. The current Act requires amendments to better align the GI system’s global standards with the sustainable, social, and economic richness of each GI in the country. Pakistan has a number of GIs, but Basmati Rice is an important GI that was first registered in the country and has huge potential in the global market [

50]. Who is the proprietor of Basmati? A case between India and Pakistan has been pending before the EU since 2020 [

51]. In July 2018, India filed a PGI for basmati rice under the Quality Schemes for Agriculture and Food Stuffs, claiming exclusive rights over the commodity in the EU. The official journal of the EU published the case in September 2020 following a preliminary examination. The EU Parliament’s regulation No. 1151/2012 allows countries to object within three months of the official publication in the EU journal. Pakistan, the largest Basmati exporter, opposed India’s claim over the GI in late 2020 [

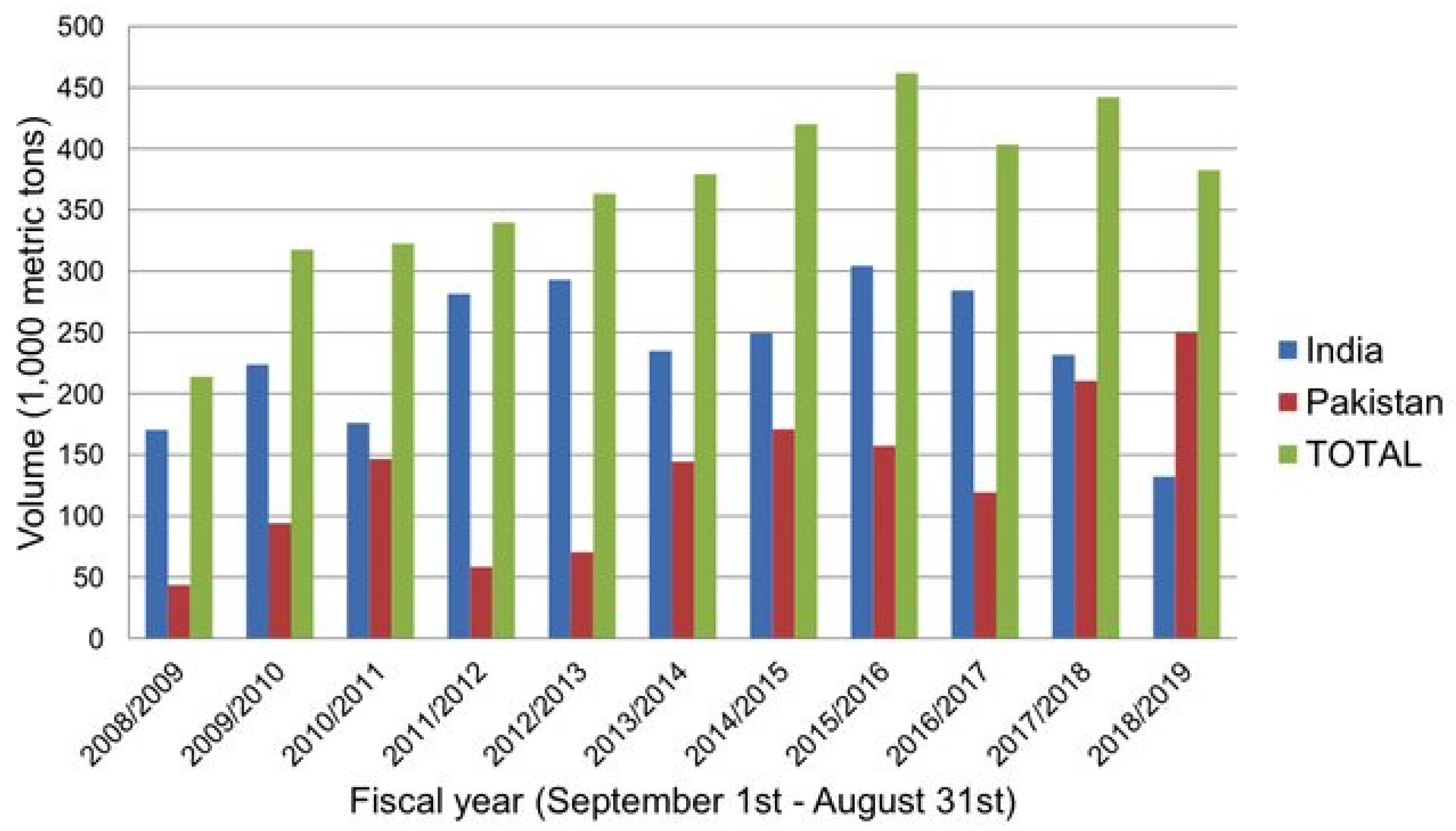

52]. Pakistan’s opposition stemmed from a transactional GI, asserting that both countries, Pakistan and India, produce basmati. The report revealed that over the past two decades, Pakistan has significantly increased its export of basmati rice to Europe, valued at USD 551.8 million in 2020. The project aims to reach US 866.5 million dollars by 2031 (Allied Market Research, 2022) [

53]. In 2021, rice imported from Pakistan will be valued at USD 329 million, compared to USD 166 million from India (European Commission, 2022a) [

54].

Figure 3 elaborates that Pakistan surpassed India in terms of imports. With 37,000 tons of organic rice exported to the EU market in 2021, it emerged as the largest exporter, surpassing India, Argentina, Cambodia, and Thailand, with a combined market share of 42.8%.

5.5. Quality Assurance: Approaches and Solutions

The uniqueness and quality of GI products make them distinctive, with the reputation of a product heavily reliant on its quality [

54]. It is essential to maintain the market quality of a product as per the requirements of consumers. In GI products, the quality of the output depends heavily on the product’s producer. A comprehensive policy for quality would benefit GI producers from the same region by establishing uniform standards. Such policy should link the product’s geographical origin to its production, processes, and methods. A specific quality associated with a particular GI region determines the main differences between products of the same class. The quality of such a product must exclusively originate from a specific geographical location, which comprises natural or human factors like soil quality, climate, craftsmanship, and local people’s skills which pass from generation to generation [

53].

The manufacturing or production process must originate from a specific, demarcated region. For instance, Hyderabadi bangles must be manufactured in Hyderabad and Multani mangoes must be produced and processed from that demarcated area on a map [

55]. Similar varieties of bangles and mangoes cannot be named after their registration in any other part of the world. This implies that the reputation of a product depends on its geographical conditions as these conditions cannot be replicated in a lab. The specific geographical conditions mark the authenticity of the product as they cannot be easily counterfeited.

Section 24 of the GI Act provides a basic regulatory framework for maintaining the quality of GIs. It requires authorized users to adhere to the book of specifications and mandates that the product must exhibit a specific quality or reputation. While this section outlines an inspection mechanism during GI registration, it does not guarantee the consistent quality of GI registered products. Furthermore, it calls for the amendment of existing mechanisms and the implementation of further efforts to certify quality, integrity, standards, or any other characteristics that the producers and authorized users should maintain. While the Act mentions an inspection process during GI registration, it does not fully guarantee the quality of each registered GI product. Despite this, the authors have observed inefficiency in the process. If the number of producers or authorized users is large, maintaining the quality of a GI product becomes an arduous task.

It is crucial that GI applications explicitly include traditional elements, which, combined with distinctive characteristics and geographical specificity, form the basis of a GIs registration. The product’s quality is intrinsically linked to its unique characteristics and geographical name, ensuring that the GI product is of high quality. To protect the reputation of GI products, the Pakistani government could implement several crucial practical measures to fortify Pakistan’s GI.

Firstly, a specific code of practice should be developed for every GI product, and an autonomous monitoring authority should be recruited or handed over to the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) under the federal government. The autonomous body may be responsible for ensuring the quality of GI products and conducting audits.

Secondly, the development and implementation of an active strategy is necessary to enhance the performance and value of GI products in the market.

Thirdly, it is crucial to enforce strict regulations, dictating stringent quality assessment and certification procedures for GI exports. By adopting these existing and proposed steps, the government can effectively bolster the authenticity and prestige of Pakistani GIs in the international market.

5.6. Enforcement and Compliance Mechanisms:

High-quality products benefit consumers around the world. Agricultural and foodstuffs require the protection of Geographical Indication, Designation of Origin (Dos), and Certificates of Special Character [

56]. The protection of GIs encourages open competition among the producers and helps the customers by providing them with information about the exact characteristics of GI products. Duplication and imitation are serious problems faced by original GI products. Sections 41 and 42 of the GI Act 2020 stipulate that infringements or false indications of GI involved can result in imprisonment for a minimum of six months and a maximum of three years, or fines of up to PKR 1 million (approx. USD 3500).

During a search conducted on the Pakistan Law Site, a judicial judgment database providing access to court rulings across the country, no records were found related to “Geographical Indication”. Pakistan has not reported any case of GI infringement to date due to the absence of GI law until 2020 [

57]. The concept of GIs is relatively new in Pakistan, primarily due to a lack of awareness about legal rights within society. Although there is an ongoing international case (See

Section 5.7) with the neighboring country India, regarding basmati rice, which is pending before the European Union, the understanding and knowledge of GIs remains limited [

58]. While the GI Act 2020 enactment marked a significant advancement, there remains a need for extensive efforts to educate the public and producers about its benefits. Such efforts would promote rural development, cultural heritage, and regional products on national and international levels. Implementing the following suggestions can help producers better influence GIs for cultural and economic benefits. This can mitigate some challenges caused by the newness of the GI Act and the indirect GI registration procedure.

5.7. Case Study of Basmati Rice

Basmati rice is a symbol of Pakistan’s culture heritage and agriculture excellence. It is known for its unique long grain, delicate aroma which is produced by 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline, and its exceptional cooking qualities, Basmati rice has been cultivated for centuries in the plain fertile of Punjab. The etymology “Basmati” is rooted in Punjab, which means “Fragrant soil”, underscoring its deep geographic and cultural connection with this product. As earlier mentioned, Basmati rice was the first GI product which was registered under the GI Act 2020. However, its GI journey has become a prominent issue in international intellectual property law, most remarkably due to a contested claim by the India in EU, which reveals several critical deficiencies in Pakistan’s GI legal infrastructure [

59].

Economically, Basmati rice is among Pakistan’s most valuable agriculture exports. In 2024 Pakistan, exported around 900,000 metric tons of Basmati rice, which earns approximately USD 3.8 billion. The rice commands the premium price globally, an average of USD 1250 per ton, which is significantly higher than the non-Basmati variants. The premium price not only supports Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves but also provides income to thousands of agricultural laborers and farmers in Punjab [

60]. The EU remains a key market for Pakistani Basmati due to its tariff free access granted under the current trade agreement. From 2020 to 2023, Pakistan’s exports to the EU more than doubled, with Basmati forming a cornerstone of this growth.

This economic success is threatened by India’s unilateral application for the protected geographical indication (PGI) status in the EU in 2018, where they claim the exclusive rights to the term “Basmati”. Pakistan delayed its response to India’s GI claims due to the absence of a dedicated GI law until 2020. TRIPS Article 22 (3) explicitly mandates that home country registration is necessary first as it requires a proof of origin, which was impossible without a functional of domestic GI system [

61]. After that, Pakistan responded by raising an official objection in accordance with EU Regulation No. 1151/2012. In a partial success, the EU acknowledges Pakistan’s position and republished the application under Article 49(5), which allows space for its reconsideration. However, such a legal tug-of-war shows Pakistan’s vulnerabilities in the case. While India submitted historical and scientific data to support its claim, Pakistan’s application lacked comparative rigor. Further complication arises from Pakistan’s GI definition extending to its 48 districts, which include non-contiguous and environmental diverse areas such as Azad Kashmir and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Such geographic overreach diluted the environmental determinism necessary to show the unique qualities of Basmati rice which arise from climate condition and specific soil [

62].

The design of Pakistan’s institutional and GI system further weakens its claim. Though the GI Act provides for registration of the producer under Part B of the registry, only the Basmati producer has been listed officially to date. It highlights governance issues in the Trade Development Authority of Pakistan, which acts as both the register and certifier and fails to engage cooperatives and grassroots producers who are the key stakeholders. In addition, Pakistan’s failure to proactively defend its Basmati claims in other jurisdictions, like Australia, reflect a lack of coordination in its international legal strategy. The GI application for Basmati was rejected in Australia, but Pakistan had no official role in its outcome [

63].

It is pertinent to note that the current dispute overshadows the history of Indo–Pak cooperation in Basmati status protection. In 1997, Indo–Pak jointly opposed a US patent on the hybrid rice market named “Texmati”. The campaign was successful because it was based on a collective understanding of Basmati as a joint heritage of the subcontinent [

64]. However, recently Indian unilateralism and Pakistan’s responsive posture deepened the lawful and diplomatic division. Interestingly, India’s application to EU does not explicitly deny the Pakistani linkage to Basmati, but the effect of granting it exclusively to India would undermine Pakistan’s ability to market its rice product under the same name in EU markets [

65].

Pakistan must adopt a multipronged strategy to protect its interest. The establishment of a GI catalog of the country, underpinned by the cultural and scientific data, is jointly essential for domestic governance and international litigation.

It has been assumed that the Basmati rice case reveals both the promise and precariousness of Pakistan’s GI regime. While representing a high-value, culturally rich product which can drive rural development and export growth, protection is compromised by weak institutional implementation, legal ambiguities, and insufficient international advocacy. Addressing such gaps is not only necessary for future GIs but also for the utility and credibility of Pakistan’s broader GI strategy.

6. Findings and Recommendations for the GI Legal Framework for Pakistan’s Sustainable Economic Growth

This study has uncovered several critical insights regarding GIs role in Pakistan’s economic development, particularly in agriculture, handicrafts, and textiles. While GIs possess significant potential to drive sustainable growth, the existing institutional and legal framework is inadequate to fully unlock this potential. In this section, the authors findings from the study are combined with actionable recommendations to address the identified key challenges and maximize the benefits of GIs for Pakistan’s sustainable economic growth.

- (1).

Legal and Institutional Gaps in GI Framework

Findings:

The GI Act 2020 introduced a legal framework for GI protection, but its implementation remains weak. Only 10 GIs have been registered to date, a number which reflects the underutilization of the system. The existing GI Act 2020 maintains a centralized ownership model under the federal government which excludes local producers and cooperatives from direct ownership.

Recommendation:

Pakistan should adopt a decentralized GI governance model, similar to the EU. Local producers should be empowered to manage their GI rights, oversee certification and marketing, and participate in the enforcement process. This approach will promote community-driven development and ensure that GIs contribute meaningfully to sustainable rural economies.

- (2).

Weak Enforcement and Counterfeit Challenges

Findings:

The current enforcement mechanisms are insufficient to prevent counterfeiting and misuse. In cases such as Basmati rice and Sindhri mangoes, fake GI claims have eroded consumer trust and reduced market prices for authentic products. Additionally, there is no post-registration quality monitoring mechanism to ensure that GI products retain their authenticity in domestic and international markets.

Recommendations:

Strengthen enforcement and surveillance: Pakistan should establish dedicated market surveillance units utilizing technologies such as radio frequency identification (RFID) to monitor GI products across the supply chain.

Post-registration inspections: Introduce mandatory post-registration inspections conducted by independent third-party certifying bodies, as practiced in the EU, to ensure compliance with established product specifications and maintain integrity.

- (3).

Lack of Awareness and Capacity Building among Producers

Findings:

A significant number of producers remain unaware of the GI system and its economic potential. This lack of awareness has resulted in low participation, especially among small-scale farmers and artisans. Furthermore, many producers lack the technical knowledge necessary to navigate the registration process or to effectively brand their products.

Recommendations:

Awareness campaigns: The government, in collaboration with NGOs and provincial institutions, should launch targeted national campaigns to educate producers on the benefits of GI registration.

Capacity building: Establish training programs focused on legal literacy, branding, certification, and quality control to build the capacity of producers and cooperatives in managing GI products.

- (4).

Absence of Effective Benefit-Sharing Mechanisms:

Findings:

The absence of a formal benefit-sharing mechanism means that the financial benefits from GI-certified products are often captured by intermediaries, such as traders and exporters, while primary producers receive minimal compensation. This undermines the goal of inclusive development and equitable value distribution.

Recommendations:

Establish a transparent benefit-sharing mechanism: Establish formal mechanisms to ensure equitable distribution of profits among stakeholders, with particular emphasis on grassroots producers.

Local community incentives: Introduce royalty schemes or licensing benefits that provide direct financial returns to artisans and farming communities involved in GI product value chains.

- (5).

Limited International Recognition and Market Access:

Findings:

One of the major challenges faced by Pakistan’s GI products is often the lack international recognition due to the absence of mutual recognition agreements and inadequate global advocacy. This limits their access to foreign markets and increases vulnerability to misappropriation.

Recommendations: International treaties and recognition: Pakistan should pursue mutual recognition agreements and integrate GI protection within Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) to secure legal recognition abroad.

International treaties and recognition: Pakistan should pursue mutual recognition agreements and integrate GI protection within Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) to secure legal recognition abroad.

Global promotion: Facilitate producer participation in international trade fairs and exhibitions to expand market access and build global awareness of Pakistani GIs.

7. Conclusions

Pakistan is an agro-based country with abundant natural resources, a strong agriculture sector, and a vibrant culture heritage, positioning it uniquely to leverage GIs for rural development, protection of traditional knowledge, and economic development. The agriculture sector is considered the backbone of the economy, contributing to 24% of its GDP and employing 37.4% of country’s workforce. Similarly, the handicraft sector is deeply rooted in traditional knowledge, and it supports 13.7% of the country’s employment, with several products which gain significant recognition nationally and internationally.

Despite this, Pakistan has only 10 GIs to date, which reflects a failure in the current legal frameworks, institutional capability, and producer engagement. The GI Act 2020 was a step forward, but its enforcement remains weak due to centralized control, inadequate surveillance, weak enforcement, and limited producer awareness. Critical findings suggest that the GI system undergoes structural reforms. This study proposes actionable recommendations which include decentralization of GI management, stronger enforcement mechanisms, and equitable benefit-sharing arrangements to ensures the fair distribution of profits from the GI products.

GIs offer Pakistan a sustainable development path by making premium revenues while protecting the socio-economic and environmental foundations of traditional production systems. By securing sustainable livelihoods for rural communities through GIs protection, Pakistan can simultaneously protect culture, provide economic development, and support environmental stewardship mainly in climate vulnerable agriculture and artisanal sectors where the traditional methods often represent centuries of ecological adaptation.

Nevertheless, GIs hold immense potential to drive economic development, specifically enhancing exports, promoting rural employment, and protecting cultural heritage. The empirical evidence from GI-registered products such as Basmati rice and Sindhri mangoes demonstrates its capability to generate significant revenue, with Sindhri mangoes alone generating USD 13.2 million revenue from the UK market. However, the full potential of GIs remains untapped, which highlights the need for systematic reforms and strategic investment in key areas.

While the study provides valuable insights into the current GI framework in Pakistan, several area still remain unexplored, necessitating further research for a long-term GI system. Future research should investigate digital governance of GIs, specifically its integration into e-commerce eco-systems. Research could assess consumer trust in online GI labels, the efficacy of digital certification systems, and how a digital platform can improve market access for small-scale producers. Given the rise in international e-commerce, this study is crucial for enhancing the international visibility and competitiveness of certified GI products.

Another promising avenue for future research can be exploring the role of GIs in promoting the tourism sector, particularly in artisan and rural communities. GI-linked products hold great potential, such as handicrafts and Sindhri mangoes farms, which could anchor cultural and eco-tourism initiatives which offer unique experiences for visitors. Comparative studies of successful models (e.g., France, India, Italy) could inform strategies for Pakistan to market GI products beside heritage sites, promoting regional economic growth.

The research areas would enable evidence-based policymaking which ensures that the development of GIs in Pakistan is inclusive, adaptive, and aligned with international trends. By focusing on digital innovation and tourism integration, future study can not only enhance the competitiveness of GI products but also protect traditional knowledge, empower local communities, and further preserve Pakistan’s rich cultural heritage for upcoming generations.