Abstract

This study explores the emerging link between digital marketing and the circular economy, situated within the broader context of sustainability and digital transformation. Through a scientometric analysis of 276 documents indexed in Scopus, the research maps the conceptual, intellectual, and collaborative landscape of this intersection. The dataset was refined using the PRISMA standards, and the analysis was carried out with the R package bibliometrix. The findings reveal a highly fragmented body of literature, with a few prolific authors and limited international cooperation. Most of the influential publications are concentrated in a small number of sources, particularly the journal Sustainability. Thematic mapping identifies growing interest in areas such as consumer perception, sustainable development, and the adoption of digital tools by micro-enterprises, while other topics like recycling or public health remain peripheral. Although the scholarly output has surged in recent years (especially during 2023 and 2024), the field still lacks coherent theoretical frameworks or dominant research schools. Overall, digital marketing appears to be a promising driver for promoting circular practices, but further applied studies and enhanced international collaboration are essential to consolidate this line of inquiry.

1. Introduction

An old Castilian proverb says that it is very difficult “putting gates on the field” [1]. Strictly speaking, this old saying serves as a metaphor for the meaning behind the invention of the W3 by T. Berners-Lee [2,3] and R. Cailliau in 1989 [4] while both were collaborators at CERN. Such was the impact of that first digital experience on all social spheres that some authors, such as Goodman [5], speak of a “digital revolution”, while, simultaneously, during the final years of the previous millennium, terms such as “circular economy” (sometimes nominalized through the simple acronym “CE”) began to be coined. These terms reflected a set of changes in global development that aimed to be as environmentally non-intrusive as possible, promoting all kinds of policies related to raising public awareness [6]. Regarding the term CE, although its origin is still not completely clear, Winans et al. [7] suggest that it may derive from the seminal book by R. Carson, Spring [8], while the Ellen MacArthur Foundation proposes that it was defined over the years by a multidisciplinary group of researchers formed by J. Lyle, W. McDonough, M. Braungart, and W. Stahel [9]. The global awareness boost regarding the gradual reduction in pollutants and environmental protection took place in “The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change” (Earth Summit—1992) [10,11], whose objectives were strengthened by the Kyoto Protocol (1997), a set of measures that provided legal certainty to the decisions made at that summit by establishing more pragmatic, effective, and legally binding actions [12].

Later, at The Millennium Summit of 2000, most world leaders signed the United Nations Millennium Declaration, in which the Millennium Development Goals were defined [13], serving as a prelude to the current 17 global Sustainable Development Goals encompassed within the so-called 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [14]. In the face of all these major milestones, marketing as a scientific discipline has not remained on the sidelines. Its multidisciplinary nature [15] has led to developing a type of marketing entirely focused on sustainable development: sustainable marketing [16,17], in which the digital transformation process has become a cornerstone [18], decisively promoting both creativity and innovation [19]. Consequently, several trends have been followed by contemporary digital marketing [20,21], for example its joint application with AI (Artificial Intelligence) [22,23] and the emergence of Digital Neuromarketing [24], just to mention two current trends. According to the preliminary definition of the World Wide Web, Berners-Lee et al. [4] stated: “The World-Wide Web (W3) initiative is a practical project designed to bring a global information universe into existence using available technology”.

Therefore, we are discussing an initiative that currently commands multiple human activities, whose initial spirit essentially remains the same. What has changed in just 20 years are the technological means through which its processes of interconnection between a myriad of individuals via cyberspace take place [25]. Consequently, detailing how digitalization has evolved is equivalent to establishing a timeline that, grosso modo, begins with the emergence in 1998 of SEO (Search Engine Optimization), an essential tool to enhance the visibility of search engines, which remains one of the main pillars of digital marketing because it helps brands to position themselves in online search results performed by users [26,27].

Search engine advertising followed soon after (2000), especially with the launch of Google AdWords (now Google Ads) [28], enabling the Pay Per Click (PPC) model [29,30], a breakthrough in digital advertising as this model allowed companies to quickly reach their target audience and measure return on investment (ROI) much more effectively [31]. As a result, software programs were developed for “click fraud detection” [32], while, at the same time, graphic applications such as “Mobile 3D Graphics API” (also known as M3G) began to be standardized through the implementation of JSR-184 documents [33].

The period between 2003 and 2010 is considered to be the time of the rise and expansion of social networks. This includes Myspace (2003) [34], Facebook (2004) [34,35], Twitter (2006) (now “X”) [36], WhatsApp (2009) [37], Instagram (2010) [38], and other online platforms that transformed consumer behavior and interaction patterns by becoming key channels for content sharing. This context fueled the popularization of Content Marketing (2008) [39], a previously unknown area where companies, as part of their commercial strategies, began using audiovisual content, blogs, and e-books, improving SEO positioning through greater consumer trust. The rise of Mobile Marketing (2013) [40] is another milestone to highlight since, for the first time, mobile traffic surpassed desktop. Brands started developing “mobile strategies”, launching ad campaigns targeting an audience that was virtually always connected via mobile phone, tablet, or any other mobile device with Internet access.

Meanwhile, Email Marketing automation (2015) [41], “The Internet’s true killer application”, in the words of Dysart [42], was enhanced by tools like Mailchimp [43] and HubSpot [44], enabling an increasingly higher degree of automation capable of creating large-scale, fully personalized email campaigns. It should be noted that, due to automation, email remains one of the most effective marketing channels for increasing sales and customer loyalty. Almost simultaneously, the Video Marketing Era (2015–2017), shaped through platforms like YouTube [45], Facebook Live [46], and TikTok [47], drove content dissemination by leveraging widespread bandwidth growth and the popularity of smartphones [48]. Video content creation helped to foster greater customer engagement, becoming an almost essential element in the design of digital strategies.

With Personalization and Big Data (2018) [49,50], it became possible to efficiently analyze massive datasets in real time, allowing for an unprecedented level of consumer segmentation. Special mention should be made of the so-called Influencer Marketing Era (2016–2020), where platforms like YouTube and Instagram fostered the rise of influencers who, in many cases, ended up becoming spokespeople or brand ambassadors. In this context, it is said that “the artificial revolutionizes the reality” [51], a statement embodied by well-known influencers such as James S. Donaldson or Felix A. U. Kjellberg (also known as MrBeast [52] and PewDiePie [53], respectively), some of whom also use their fame and prestige to support purely charitable causes, completely removed from profit [52]. In the current landscape, AI is playing an essential role in the development of digital marketing by enhancing systematic automation, deepening client personalization through real-time data analysis, personalized content creation, and optimized customer service. Among these cutting-edge technology sets, we find ChatGPT [54,55,56], the Chinese initiative DeepSeek [57], the Spanish project ALIA [58], and Grok [59], owned by the controversial entrepreneur E. R. Musk, current Administrator of the Department of Government Efficiency for the U.S. government.

Despite the growing research on digital marketing [60,61], the specific role that digital marketing currently plays in supporting and consolidating the various circular economy models that have emerged over time has received relatively limited attention from the academic community. While some studies have focused on digitalization as a key enabler of circular strategies [62,63,64], few have explored the main functions of digital marketing in the context of the circular economy, such as in terms of consumer engagement, co-creation of value, or content creation. However, recent works such as Leal et al. [65] and Nobre and Tavares [66] highlight the need to align sustainability goals with marketing communication strategies. In any case, a systematic analysis that jointly examines the existing connections between digital marketing and the circular economy is still lacking.

Therefore, this study seeks to address this gap through an exhaustive bibliometric analysis, which includes, among other elements, thematic trends, the most influential contributors and university centers, as well as a strategic diagram that maps the current structure of research connecting digital marketing and the circular economy. It is also worth noting that bibliometric analyses are particularly well suited for rigorously examining this relationship insofar as, as noted by Põder [67], they are limited to efficiently describing objective processes.

The set of procedures included in the R package “Bibliometrix” (version 5.0.0) [68] has been implemented as the bibliometric toolset in this study. This package provides a substantial number of approaches for the tabulation, processing, and visualization of bibliometric data [69], also enabling content analysis techniques that, among other functions, summarize the current state of a given field of knowledge [70]. To carry out our study, we have structured it as follows. In Section 2, we define the bibliographic database used, which was refined using the PRISMA statement (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) [71]. Then, in Section 3, we present the results obtained, which are duly discussed in Section 4. This work concludes in Section 5, where we list the main findings of the research, its limitations, and, as a final note, a set of practical policy recommendations that may be implemented based on the results of this study.

2. Materials and Methods

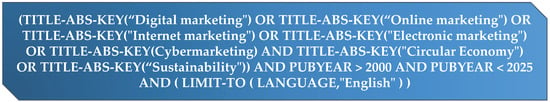

When conducting the bibliometric analysis, the first step was to decide which scientific database to use. While it is true that the number of specialized scientific databases has increased in recent years, there are essentially two that receive the most attention from the scientific community: Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus [72,73]. In fact, most bibliometric analyses originate from these two databases [74]. In this regard, we opted to implement the Scopus database as it is the most comprehensive scientific database, with records dating back to 1788, before the French Revolution (specifically, “Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh” [75]). Moreover, Scopus covers 20% more citations than WoS [76] and, likewise, includes a wider range of scientific disciplines [74], which is essential for our research when examining the multidisciplinarity of digital marketing [15] in the current context of the circular economy. Subsequently, a Boolean search was conducted within that database. However, the term digital marketing [77,78,79] is a neologism [80], that is, a very recently created word that lacks a univocal meaning for all researchers. Hence, there are several analogous terms, such as “online marketing” [81,82,83], understood as the set of marketing strategies implemented through the Internet; “Internet marketing” [84,85,86], focused on tactics and strategies using the web as the main communication channel; “electronic marketing” [87,88], which broadly covers the use of electronic media for marketing activities; and “cybermarketing” [33,89], also used to describe marketing within the digital sphere. The Boolean search conducted is outlined in Figure 1. As shown, using the Boolean operators AND–OR, a search was performed covering the 2000–2024 period for the aforementioned terms in relation to circular economy and digital marketing, within the Title, Abstract, and Keywords fields. It should be emphasized that the selection of keywords was by no means random but rather based on a consolidation of terms synonymous with digital marketing following a procedure very similar to that of Munteanu et al. [90], in this case focused on a bibliometric perspective that combines sustainable financial strategies with the circular economy. In any case, it can be observed that the keywords chosen made it possible to carry out the bibliometric analysis in a robust manner, such that removing any of these keywords would have resulted in a significantly lower number of records than obtained in this study (276), which would have made any coherent bibliometric analysis unfeasible. As with any bibliometric analysis, it is assumed that no records prior to the year 2000 satisfy the keywords derived from the Boolean search applied (see Figure 1). The upper boundary was set at 2024 given that 2025 had not yet concluded at the time of this study and its partial inclusion would have lacked analytical significance. In order to homogenize the results, the search was limited to bibliographic records in English. First of all, it is obvious to determine that most of the academic literature is written in English, a fact even more evident if we limit ourselves to the pre-existing relationship between digital marketing and the circular economy. If this search had not been restricted to English, only 7 items would have been included in the database to be implemented in Bibliometrix, six in Spanish, and one in Indonesian. Regardless of the fact that these contributions would have been residual if added to the database (around 2.54% of the records), carrying out any type of analysis between English and Spanish or Indonesian would have been entirely unproductive, by mixing, for example, co-words from different languages. That is why we established that English was used in order to homogenize the analysis of this research.

Figure 1.

Boolean search implemented in this research.

Data and Methodology

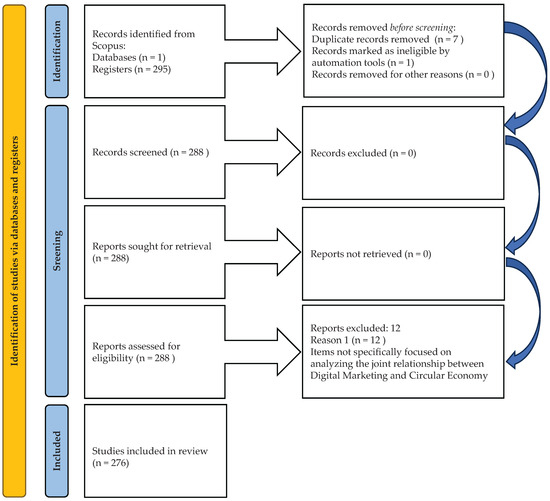

From the previous search, a bibtex bibliographic file was obtained [91], suitable for bibliometric analysis, which subsequently had to be refined according to the PRISMA 2020 statement, as shown in the flowchart inserted in Figure 2, allowing for the elimination of incomplete, incorrect, duplicate items [92], or those not directly related to the object of study.

Figure 2.

PRISMA 2020 flowchart implemented in this research.

Regarding the choice in bibliometric tool, we start from the premise that the proliferation of bibliometric applications has been enormous in recent times [93], paralleling the growing interest of the scientific community in this field of knowledge. We could have chosen from among the many available, such as Bibexcel [94], CiteSpace [95,96], Gephi [97], HistCite [98,99], Pajek [100], SCIMAT [101], SCI2 [97,102], UCINET [103], or VOSviewer [98,104,105]. However, in our case, the goal was not to determine which bibliometric application is better or worse for analyzing a given dataset derived from a scientific database but rather which one provides a simultaneous overview or “helicopter view” of the greatest number of dimensions. This expression is widely extended in the scientific literature (see, i.e., [106,107]), which serves as an epitome intended to describe a generalist overview [108] of a given phenomenon.

Therefore, we chose to implement the set of bibliometric procedures contained in Bibliometrix (version 5.0.0) [68], which has become a standard in scientometric research as it jointly analyzes eight dimensions that can a priori be considered essential: (1) overview, (2) sources, (3) authors, (4) documents, (5) clustering by coupling (i.e., per author), (6) conceptual structure, (7) intellectual structure, and (8) social structure. It is worth noting that this tool has been reliably used in many other fields of knowledge, such as Cooperative Economy Research [96], Green Finance [109], Image Recognition [95], Business Organization [110], and Post-Disaster Reconstruction [111], to name just a few examples. The core of the research is presented in Table 1, covering the analysis period from 2001 to 2024 across a total of 185 different sources.

Table 1.

Bibliographic database analyzed: main information and characteristics.

The 276 items ultimately selected after applying the PRISMA flowchart (see Figure 2) represent, at first glance, an adequate sample size for the dataset analyzed as Seglen [112] establishes a minimum range of 50–100 items, while Glänzel and Moed [113] estimate that the minimum threshold should be around 50 for the results to be considered minimally consistent. In the absence of a previous benchmarking study to contrast the resulting bibliographic database, it is striking that single authorship predominates. There is still a very low level of transnational cooperation in multi-authored works (just over one-sixth), and, although articles are the primary type of document, they account for just over 50% of the dataset. From this, we infer that the joint analysis of digital marketing and the circular economy is still in its early stages, an entirely reasonable conclusion given the novelty implicit in both terms.

This is supported by the average age per document, which is just over three years, and the relatively low average number of citations per document (for a total of 2501), which stands at around 9 citations. Another noteworthy fact derived from Table 1 is that not a developed country but rather a developing one, Indonesia, holds the highest scientific production during the analyzed period. Clearly, this demonstrates that applications and variants of digital marketing within the context of the circular economy represent a global phenomenon that today attracts, or is beginning to attract, the attention of practically all countries worldwide.

3. Results

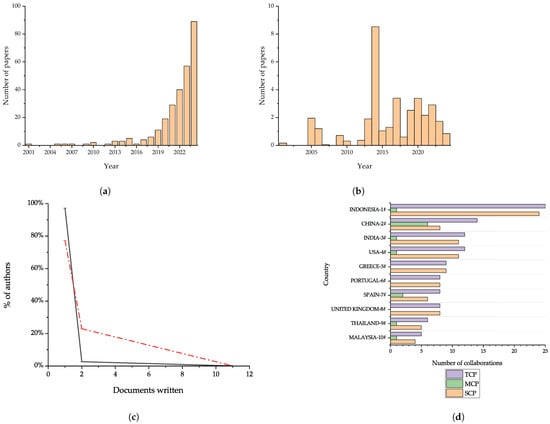

First, Figure 3 details the main characteristics of the dataset analyzed. Regarding the evolution of total scientific production—Figure 3a—it is noted that, between 2001 and 2012, the number of works was merely anecdotal or sporadic, while, between 2013 and 2014, practically exponential growth began, observable until the end of the time horizon studied.

Figure 3.

Total scientific production, evolution of the number of citations, Lotka’s law, and the top ten countries in scientific production by type of authorship (single or multiple). All graphs refer to the period under review. Source: own elaboration.

In turn, the number of citations—Figure 3b—was also rather low until the aforementioned period (2013–2014), improving somewhat from then on. According to Lotka’s law [114]—Figure 3c—a significant fact in the dataset can be illustrated: scientific production is mainly concentrated in a relatively small group of very prolific authors, while the vast majority of authors contribute a rather limited number of bibliographic items. The ranking of scientific production by country, based on the origin of the respective corresponding authors—Figure 3d—confirms some stylized facts previously indicated in Table 1. Indeed, if we break down the scientific production carried out in each country based on this criterion (TCP = Total Country Production by corresponding author) into two parts, SCP and MCP (Single Country Production vs. Multiple Country Production), it can be seen that publications carried out among authors from more than one country (that is, the degree of intra-country collaboration) are still quite limited. Likewise, in this top ten, we can observe that, alongside Indonesia in first place and the developed countries, there are also several emerging or developing countries interested in analyzing the degree and nature of the relationship between digital marketing and the circular economy (i.e., India, Thailand, and Malaysia).

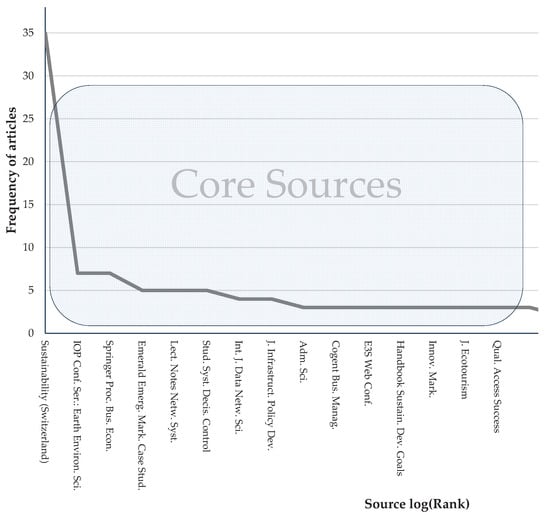

Figure 4 outlines Bradford’s law [115], a prototypical bibliometric procedure based on subdividing bibliographic datasets into groups or clusters of equal size so that the number of records increases geometrically, resulting in three clearly differentiated zones: (1) the peripheral zone, composed of contributions on the subject that appear completely sporadically, (2) the intermediate zone, composed of a much broader group of records that publish more specialized works but in much lower quantity, and, finally, (3) core sources, represented by a relatively small number of highly specialized contributions on the object of study, identifying the most relevant sources for the research. In our specific case, Figure 4 summarizes this core, highlighting sources such as Sustainability (mainly), IOP Conference Series, Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics, Emerald Emerging Markets Case Studies, and Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems.

Figure 4.

Bradford’s law of the most representative publications during the period analyzed. Source: own elaboration.

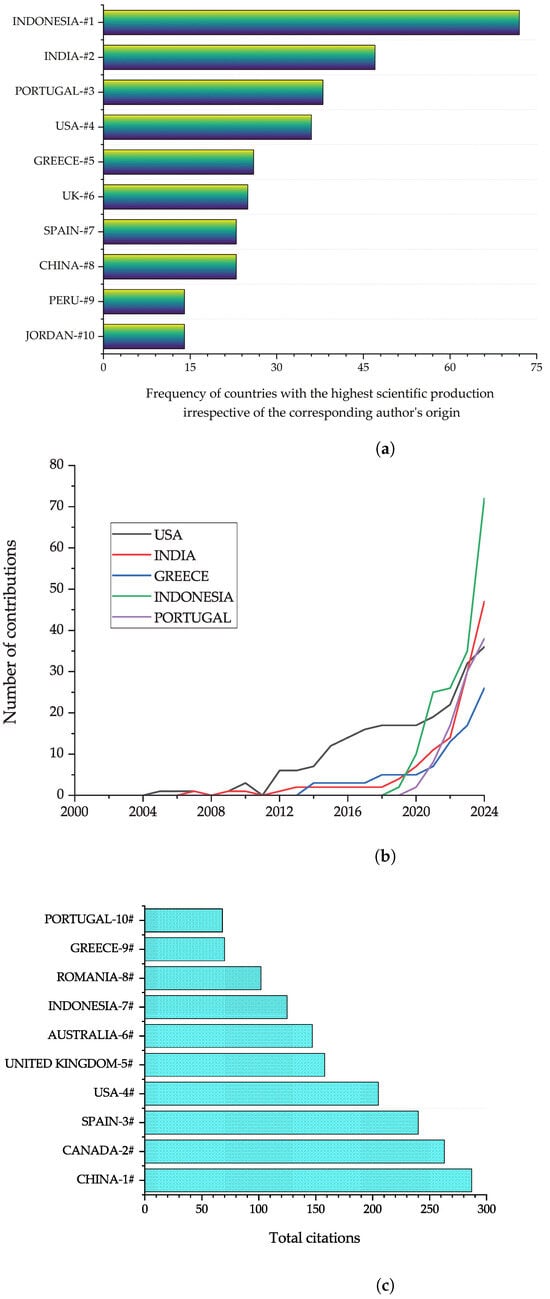

Next, Figure 5 deepens the analysis of the countries that contributed most. For example, Figure 5a outlines the top ten ranking of countries with the highest scientific production regardless of the origin of the corresponding author, while Figure 5b shows the temporal evolution of the scientific production of the top five countries in this ranking: Indonesia, China, India, United States, and Greece.

Figure 5.

The ten most productive countries in this field of knowledge, the evolution of the five countries with the highest scientific production, and the ten countries with the highest number of citations over the period considered. Source: own elaboration.

Again, we can verify that, at the beginning of the period, the contributions were quite sporadic (limited to the USA and India), with the rest of the countries joining soon after: Greece in 2014, Indonesia in 2019, and Portugal in 2020. In this sense, two circumstances should be noted: the great surge in scientific production occurred during the last two years of the study period (2023–2024) to the extent that more than 50% of the total production is concentrated in that biennium. On the other hand, as indicated previously, the 2013–2014 subperiod marks the beginning of the acceleration in the growth of scientific production. This turning point may likely be due to the emergence of seminal works in this area, such as Van Mierlo [116], Andreopoulou et al. [117], and Li et al. [118], focused, respectively, on digital health, the duality between sustainable development and rural tourism, and paid search marketing. This diversity, of course, serves to emphasize the multidisciplinary nature of digital marketing, even more so when confronted with the circular economy. Finally, Figure 5c presents a ranking of countries based not on the origin of the corresponding author (as in Figure 5b) but on the number of citations received by each country. Here, the panorama is entirely different from that of Figure 5b as the ranking is led by developed countries renowned for digitalization, such as China, Canada, Spain, the USA, and the United Kingdom, all of which show very high average citation numbers (20.5, 131.5, 30, 17.1, and 19.8, respectively).

For its part, Table 2 lists the 10 most cited contributions in the dataset, disaggregated by total citations, total citations per year, and normalized total citations, that is, total citations divided by the average number of citations per year and field. Considering that this top ten accumulates over half the citations in the dataset and that one source, Sustainability (Switzerland), overwhelmingly dominates the rest, this confirms what was previously stated in the core sources of Bradford’s law (see Figure 4) as a very limited number of publications end up becoming the most important sources in the field. Consequently, Table 3 displays a triple ranking of authors (Panel A), sources (Panel B), and affiliations (Panel C), using six key indicators: H index, G index, M index, TC (total citations), NP (number of publications), and PY Start (publication year start). The H index [119] is defined as a hypothetical maximum number h for a given entity (researcher, institution, etc.) that has published h bibliographic items that have been cited at least h times.

The G [120] and M [121] indexes are derived from the former: while the first represents the maximum number g such that the most cited works together received at least g2 citations, the latter is calculated by dividing a given H index by the total number of years since the first publication. Regarding the author ranking (Panel A), apart from the exceptions represented by Z. Andreopoulou [117], D. Chhabra [122,123], and C. Koliouska [117], whose initial contributions date from 2014 to 2015, the rest of the works were carried out quite recently, or even contemporaneously (2020–2023). Clearly, the authors in this ranking present very similar metrics (i.e., H index, G index, and NP all equal to 2). Although very small, these figures confirm Lotka’s law (see Figure 3c) inasmuch as the scientific output is concentrated in a relatively small number of authors on this topic. Likewise, as shown in the source ranking (Panel B), we once again confirm the pattern established by Bradford’s law [115] as only one source, Sustainability (Switzerland), accumulates the highest number of publications in the dataset, far ahead of the rest. Indeed, this journal leads in the number of academic items published in this field (35 in total), with H index and G index values of 15 and 23, respectively.

Table 2.

Top ten of the ten most relevant contributions in this specific field of knowledge.

Table 2.

Top ten of the ten most relevant contributions in this specific field of knowledge.

| Paper | Total Citations | *TCs per Year | Normalized *TCs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Van Mierlo [116] | 257 | 21.417 | 2.511 |

| Bassamzadeh and Ghanem [124] | 89 | 9.889 | 2.918 |

| Kapoor et al. [125] | 85 | 21.250 | 7.296 |

| Low et al. [126] | 84 | 14.000 | 4.145 |

| Shen and Chou [127] | 84 | 21.000 | 7.210 |

| Ivars-Baidal et al. [128] | 81 | 16.200 | 7.505 |

| Harries et al. [129] | 70 | 5.385 | 2.838 |

| Diez-Martin et al. [130] | 61 | 8.714 | 3.459 |

| Dumitriu et al. [131] | 59 | 8.429 | 3.345 |

| León-Quismondo et al. [132] | 51 | 8.500 | 2.517 |

Source: own elaboration. *TC: Total Citations.

It also spans a relatively long period (2018–2024), with the initial work by Jankowski et al. [133] on viral marketing and more recent studies such as Piras [134], which conducts a thorough review of technological innovation in the wine industry.

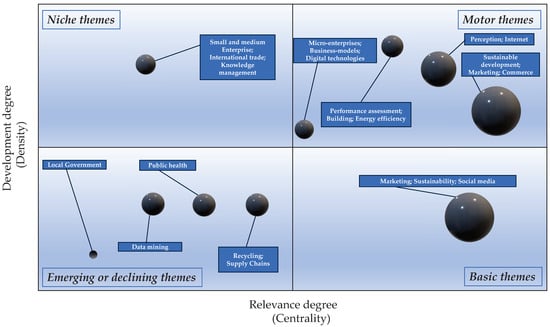

Interestingly, within the ranking of the ten most productive academic institutions in this research field (Panel C), none of the countries represented appear more than once. Moreover, each institution has produced a relatively small number of contributions, ranging from three to six. This can largely be attributed to the fact that this research field is still emerging (barely over 20 years old) and remains highly fragmented both in terms of country distribution and thematic focus when linking digital marketing with the circular economy. Regarding the characterization and evolution of the different topics and research lines analyzed, Figure 6 presents their current taxonomy through a strategic diagram. This method implements Fuzzy Sets Theory (FST) [135,136] in bibliometric analysis using co-word analysis [137,138] to study various themes based on two parameters: “Callon’s density” and “Callon’s centrality” [137,138]. In this sense, centrality measures the degree of interaction of a theme (grouped in a given cluster) with other themes, being an indicator of its importance or external relevance within the scientific field analyzed, while density reflects the degree of internal cohesion of a theme (grouped in a given cluster), determining how developed and specialized that thematic cluster is. It should also be noted that the strategic diagram is oriented toward making inferences and analyzing the evolution of a scientific domain, being much more than a merely descriptive or exploratory analysis [139].

Figure 6.

Strategic diagram of the 4 types of themes or lines of research inherent in this explicit field of knowledge. Source: own elaboration.

Table 3.

Top ten authors, sources, and affiliations in this specific field of knowledge.

Table 3.

Top ten authors, sources, and affiliations in this specific field of knowledge.

| Panel A: Top Ten Authors | ||||||

| Author | Index | index | Index | TC | NP | PY Start |

| ALMANSOUR M | 2 | 2 | 0.500 | 53 | 2 | 2022 |

| ANDREOPOULOU Z | 2 | 2 | 0.167 | 32 | 2 | 2014 |

| BALAJI MS | 2 | 2 | 0.400 | 100 | 2 | 2021 |

| CHHABRA D | 2 | 2 | 0.182 | 7 | 2 | 2015 |

| GIANNAKOPOULOS NT | 2 | 2 | 0.667 | 10 | 2 | 2023 |

| KANELLOS N | 2 | 2 | 0.667 | 10 | 2 | 2023 |

| KOLIOUSKA C | 2 | 2 | 0.167 | 32 | 2 | 2014 |

| MENON S | 2 | 2 | 0.333 | 23 | 2 | 2020 |

| NASIOPOULOS DK | 2 | 2 | 0.500 | 14 | 2 | 2022 |

| SAKAS DP | 2 | 2 | 0.667 | 10 | 2 | 2023 |

| Panel B: Top Ten Sources | ||||||

| Source | Index | Index | Index | TC | NP | PY Start |

| SUSTAINABILITY (SWITZERLAND) | 15 | 23 | 1.875 | 581 | 35 | 2018 |

| INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF DATA AND NETWORK SCIENCE | 3 | 4 | 0.600 | 63 | 4 | 2021 |

| IOP CONFERENCE SERIES: EARTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE | 3 | 4 | 0.600 | 18 | 7 | 2021 |

| JOURNAL OF ECOTOURISM | 3 | 3 | 0.143 | 56 | 3 | 2005 |

| ADMINISTRATIVE SCIENCES | 2 | 2 | 0.667 | 8 | 3 | 2023 |

| COGENT BUSINESS AND MANAGEMENT | 2 | 3 | 1.000 | 24 | 3 | 2024 |

| EMERALD EMERGING MARKETS CASE STUDIES | 2 | 2 | 0.154 | 8 | 5 | 2013 |

| GLOBAL APPLICATIONS OF THE INTERNET OF THINGS IN DIGITAL MARKETING | 2 | 2 | 0.667 | 12 | 2 | 2023 |

| INNOVATIVE MARKETING | 2 | 3 | 0.500 | 19 | 3 | 2022 |

| JOURNAL OF GLOBAL SCHOLARS OF MARKETING SCIENCE: BRIDGING ASIA AND THE WORLD | 2 | 2 | 0.500 | 51 | 2 | 2022 |

| Panel C: Top Ten Affiliations | ||||||

| Affiliation | Papers | |||||

| AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY OF ATHENS (Greece) | 6 | |||||

| SZÉCHENYI ISTVÁN UNIVERSITY (Hungary) | 6 | |||||

| UNIVERSITAS PADJADJARAN (Indonesia) | 5 | |||||

| CHULALONGKORN UNIVERSITY (Thailand) | 4 | |||||

| KRISTU JAYANTI COLLEGE -AUTONOMOUS- (India) | 4 | |||||

| AHLIA UNIVERSITY (Bahrain) | 3 | |||||

| INSTITUTE OF GEOGRAPHY (Romania) | 3 | |||||

| JAMES COOK UNIVERSITY (Australia) | 3 | |||||

| UNIVERSIDAD SEÑOR DE SIPÁN (Peru) | 3 | |||||

| UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA (Portugal) | 3 | |||||

Source: own elaboration.

Thus, by plotting these parameters along coordinate axes (x-axis: Callon’s centrality; y-axis: Callon’s density), we obtain a strategic diagram chart that visually classifies [140] the research into four types of topics depending on their quadrant within the bidimensional space [138,141,142,143,144,145]. This method allows us to distinguish the following types of themes [145]:

(1) Upper-right quadrant (“motor themes”), well-developed and essential for structuring a specific field of research.

(2) Upper-left quadrant (“niche themes”), characterized by strong internal links but weak external ones. These are highly specialized topics and therefore of limited or peripheral importance to the overall field.

(3) Lower-left quadrant (“emerging or declining themes”), poorly developed and thus marginal, either emerging or fading topics.

(4) Lower-right quadrant (“basic themes”), important to the field but still underdeveloped, often transversal, being overly generic or foundational. Accordingly, Figure 6 presents this thematic classification, displaying in each quadrant the clusters grouped using the walktrap algorithm [146] across a total of 250 keywords. Specifically, the following themes have been identified per quadrant. Each cluster’s size is proportional to the number of keywords it contains; the cluster title corresponds to the most relevant keyword; and, for the larger clusters (perception, sustainable development, and marketing), the five most relevant terms are included as follows:

- Quadrant I: Motor Themes

- •

- Cluster #1 (Perception): “perception”, “Internet”, “consumption behavior”, “humans”, and “agriculture”.

- •

- Cluster #2 (Micro-Enterprises): “micro-enterprises”, “business models”, and “digital technologies”.

- •

- Cluster #3 (Sustainable Development): “sustainable development”, “digital marketing”, “commerce”, “electronic commerce”, and “online marketing”.

- •

- Cluster #4 (Performance Assessment): “performance assessment”, “building”, “energy efficiency”, “knowledge-based systems”, “machine learning”, and “Pacific Northwest”.

- Quadrant II: Niche Themes

- •

- Cluster #5 (Small and Medium Enterprises): “small and medium enterprises”, “international trade”, and “knowledge management”.

- Quadrant III: Emerging or Declining Themes

- •

- Cluster #6 (Recycling): “recycling” and “supply chains”.

- •

- Cluster #7 (Data Mining): “data mining” and “research focus”.

- •

- Cluster #8 (Public Health): “public health” and “United States”.

- •

- Cluster #9 (Local Government): “local government”.

- Quadrant IV: Basic Themes

- •

- Cluster #10 (Marketing): “marketing”, “sustainability”, “social media”, “strategic approach”, and “business development”.

4. Discussion

The results of this research define it as a field of knowledge still in its early stages, highly atomized in terms of the various topics it addresses, given that it is just over 20 years old. Indeed, it is a multidisciplinary (if not multifaceted) field that encompasses a wide range of themes. However, the approach of digital marketing associated with the circular economy represents an emerging area that has not yet been fully explored. In other words, the potential of digital marketing strategies to advance circular business models is truly promising, but, in light of our results, it would require more practical studies and direct applications to ensure its consolidation. Likewise, regarding scientific output, there has been a substantial increase in research on digital marketing vs. the circular economy, especially in the 2023–2024 biennium. This degree of growth highlights the rising global interest in this field of knowledge, considering that, while most contributions come from developed countries, nations like Indonesia are leading the research, indicating a potential global expansion of the topic under study.

Despite the steady growth in the number of publications, cross-border collaboration remains relatively scarce, with only a limited number of works involving co-authorship between institutions from different nations. This indicates that, although the research activity is expanding, the field has yet to attain a truly global scope, which could initially limit both its influence and evolution. Likewise, as this area of study is still in its early stages, distinct “Schools of Thought” (understood as well-established academic groups or research institutions focusing on particular theoretical or methodological lines) have not yet formed, in contrast to more mature disciplines (see, for instance, Parrales Choez et al. [147] in the scientometric study of Credit Unions). In terms of academic dissemination, journals such as Sustainability have become key venues for publishing relevant research, serving as focal points for scholarly exchange regarding the intersection of digital marketing and the circular economy.

If we evaluate the findings of the strategic diagram (Figure 6) in light of the academic literature, we observe that the results are conclusive. Indeed, Quadrant I (high centrality and high density, motor themes) represents key areas with the greatest potential for impact and therefore indicates future research directions. This is the case of “consumer perception” regarding sustainable products and services, which is crucial for the strengthening of the circular economy, with digital marketing playing a fundamental role in facilitating such perception [148]. A similar case is that of “micro-enterprises”, which tend to integrate circular business models linked with digital marketing [149], or “sustainable development”, which is reinforced by the educational potential that digital marketing can have on consumers, encouraging fully sustainable purchasing decisions [150]. As for “performance assessment”, this term is essential for measuring the effectiveness of digital marketing strategies on the circular economy while also optimizing resources and improving their effectiveness [151]. In contrast to Quadrant I, Quadrant III (low centrality and low density, emerging or declining themes) includes those topics that may either disappear or become future opportunities over time. These are themes such as “recycling” [152] or “data mining”, which help to identify sustainable consumption patterns in order to personalize digital marketing strategies [153]. Within this quadrant of marginal topics, we can also find themes like “public health”, considering that digital marketing can influence the perception of sustainable products as beneficial for the health of broader society [154], or “local government”, bearing in mind that these governmental entities may implement digital tools aimed at adopting a circular economy within the public sector [152].

Meanwhile, Quadrant II (low centrality and high density, niche themes) is based on highly specialized topics that still have limited impacts in academia. This is the case, for example, for “small and medium enterprises”, which apply circular economy practices in a fragmented way depending on the sector and access to digital resources [155]. Lastly, Quadrant IV (high centrality and low density, basic themes) identifies works that are fundamental to the field but still underdeveloped, such as the term “marketing”, understanding that its digital implementation is essential for the development and consolidation of the circular economy, although it currently requires greater specialization and a higher degree of practical implementation.

On the other hand, it should be noted that research in the field of digital marketing and the circular economy remains limited, indicating the need to explore this emerging area. The results show that the core sources for publication are less diverse. Marketing and digital marketing journals appear to have shown limited interest thus far in publishing research related to the circular economy. On the flip side, increased interdisciplinarity will enhance the importance of the field, attracting marketing scholars to study the relationship with sustainability and the circular economy. This can broaden the discourse about sustainability marketing to contribute to a circular economy.

Furthermore, the results revealed the most active nations and institutions publishing on digital marketing and the circular economy. These findings encourage future researchers to find opportunities for collaboration while filling the research gap by investigating the topic in different countries and organizational contexts. Moreover, the cluster analysis revealed that the most relevant keyword was ‘perception’, followed by ‘sustainable development’ and ‘marketing’. Perception in terms of consumer behavior is related to digital marketing and the circular economy. Consumer decision-making is shaped by marketing activities and plays a crucial role in the transition to a circular economy. Consumers’ sustainable lifestyle, environmentally conscious behavior, and sustainable consumption patterns support the circular economy.

Consumers’ perception of sustainable products and sustainable brands reinforces sustainable corporate behavior. Consumer attitudes and demand for products and services produced using circular economy principles influence companies’ decisions regarding sustainable production processes. In this respect, sustainable consumption and production contribute to the circular economy. Designing products that are repairable and recyclable but also promoting sustainability practices and encouraging product reuse and recycling will reduce waste, prevent the depletion of natural resources, and protect the environment. In this sense, digital marketing impacts consumption patterns and shapes consumer sustainability behavior. Augmented digitalization ensures public outreach through digital channels to raise awareness of circular economy principles and sustainability issues. Thus, digital marketing can be used to foster the circular economy’s aims of eliminating waste and pollution, extending product lifespans, and regenerating natural resources.

5. Conclusions

This research has analyzed the growing relationship between digital marketing and the circular economy, a field of knowledge that is still in its early stages and has begun to attract the interest of the scientific community over the past 20–25 years. Interestingly, both the rise of sustainability awareness in the business environment [156] and the emergence of bibliometric analysis procedures [93] have occurred almost simultaneously. In other words, this research has focused on a novel field of study, applying equally novel analytical tools, which, at first glance, reveal a domain characterized by high thematic dispersion, accompanied by a low concentration of cited works that also exhibit very limited international collaboration. In this sense, it has been verified that, although there is certain interest among researchers in exploring how digital marketing can give rise to strategies and sustainable models within the scope of the circular economy, the body of knowledge generated through scientific production lacks sufficient robustness to assert that a cohesive theoretical framework truly exists. Hence, the link between digital marketing and the circular economy has not yet been sufficiently explored despite its remarkable potential [157].

In any case, throughout this article, thematic areas have been identified that, both due to their conceptual depth and practical projection, have begun to consolidate as strategic cores within the conceptual framework of the digital marketing vs. circular economy relationship. Relevant topics have been detected, such as consumer perception regarding the emergence of sustainable products, or the gradual incorporation of micro-enterprises into circular production and consumption models. These themes indicate that digital marketing is more than just a communication channel; it can also become a key element in creating and promoting responsible consumption environments.

With regard to the geographical distribution of the field of knowledge analyzed, the results show a plural, and somewhat unexpected, scenario in which, although developed economies lead the research, several emerging countries are beginning to stand out by contributing an increasing number of publications.

In summary, this article has helped to clarify the academic debate on the role that digital marketing can play in the transition towards circular economic models based on the premise that, although interest in this synergy has grown significantly in recent years, a higher level of theoretical integration is still necessary, as well as the adoption of more homogeneous methodological approaches—although such issues may stem from the multidisciplinary nature of this specific field of knowledge.

As with any other research, this study also presents certain limitations. Primarily, as previously noted, the absence of a universally accepted definition of digital marketing—coupled with the fact that, according to Kirchherr et al. [155], there are 114 different definitions—poses a challenge that a priori may constrain the establishment of a one-to-one relationship between the two key elements of this study.

Another plausible limitation lies in the fact that we did not employ an ad hoc procedure for selecting keywords, such as a systematic literature review, prior frequency analysis, or consultation with experts. While these strategies could potentially have enhanced the rigor of our research, they would also have considerably delayed the process. Moreover, none of them guarantee a “perfect” keyword selection. In this regard, the argument of Chen and Xiao [158] is reinforced: to date, no method exists that can automatically identify keywords optimally. Nevertheless, the development of a standardized keyword selection procedure represents a valuable line of future research.

A further limitation concerns the use of a single database (Scopus) without incorporating others, such as Web of Science. Although using multiple databases could indeed have enriched our study, this represents one of the most significant challenges in bibliometric research. Beyond the need to deal with different metadata structures across platforms, there are also substantial operational difficulties given the persistent differences in journal coverage across scientific domains and the variations in citation indexes due to the differing indexing policies [159].

Future studies can focus on the digital marketing channels that are best for promoting circular economy principles. Moreover, studies can address how digital marketing affects consumer perceptions of sustainability and the circular economy, which further influence business decisions. It is noteworthy that societal expectations regarding sustainability can exceed companies’ abilities to adapt to the circular economy. Consequently, innovative solutions should be found through future research. Companies using digital marketing can create realistic expectations and communicate with stakeholders, disclosing information about their achievements towards a sustainable future. Therefore, future studies should analyze digital marketing strategies for companies to implement sustainability goals and communicate their achievements. Furthermore, international cooperation in research on the relationship between the circular economy and digital marketing will enrich the relevant literature by adding insights from different perspectives.

To effectively promote international research in digital marketing and the circular economy, collaborative research projects that bridge geographical and disciplinary boundaries should be encouraged. Providing funding and resources for international research teams and creating platforms to share findings will connect researchers across different geographical locations and academic disciplines. Thus, future studies should delve deeper into examining strategies to promote international cooperation in the field of digital marketing and the circular economy.

Finally, it is worth emphasizing that, based on the strategic diagram developed, it has been possible to draw a series of inferences regarding the categorization of the pre-existing research lines between digital marketing and the circular economy. However, the results should be interpreted with caution within a short-term context as any type of prediction (especially those based on the long term) will always be rather uncertain and, in any case, not sufficiently meaningful [160].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.G., P.Z., P.d.F.M., and P.A.M.-C.; methodology, I.G., P.Z., P.d.F.M., and P.A.M.-C.; software, I.G., P.Z., P.d.F.M., and P.A.M.-C.; validation, I.G., P.Z., P.d.F.M., and P.A.M.-C.; formal analysis, I.G., P.Z., P.d.F.M., and P.A.M.-C.; investigation, I.G., P.Z., P.d.F.M., and P.A.M.-C.; resources, I.G., P.Z., P.d.F.M., and P.A.M.-C.; data curation, I.G., P.Z., P.d.F.M., and P.A.M.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, I.G., P.Z., P.d.F.M., and P.A.M.-C.; writing—review and editing, I.G., P.Z., P.d.F.M., and P.A.M.-C.; visualization, I.G., P.Z., P.d.F.M., and P.A.M.-C.; supervision, I.G., P.Z., P.d.F.M., and P.A.M.-C.; project administration, I.G., P.Z., P.d.F.M., and P.A.M.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data underlying this research are fully available to the scientific community on request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| CE | Circular Economy |

| CERN | Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire |

| M3G | Mobile 3D Graphics API |

| PPC | Pay Per Click |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| SEO | Search Engine Optimization |

| SJR | Java Specification Request |

| ROI | Return on Investment |

| WoS | Web of Science |

| WWW (W3) | World Wide Web |

References

- D.R.A.E. “Poner Puertas al Campo”: Para dar a Entender la Imposibilidad de Poner líMites a lo Que no los Admite. [“Putting Gates on the Field”: To Imply the Impossibility of Setting Limits to What Does Not Admit Them.]. 2025. Available online: https://dle.rae.es/puerta (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Kilbane, D. Tim Berners-Lee: The Internet’s creator looks to the next evolution. Electron. Des. 2004, 52, 90. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, A.M. Tim Berners-Lee. Kybernetes 1998, 27, 86–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berners-Lee, T.; Cailliau, R.; Groff, J.; Pollermann, B. World-Wide Web: The Information Universe. Internet Res. 1992, 2, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, C. The Digital Revolution: Art in the ComputerAge. Art J. 1990, 49, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Cervantes, P.A.; Valls Martínez, M.d.C. The plastification of minds. In Socially Responsible Plastic—Is It Possible? Crowther, D., Quoquab Habib, F., Eds.; Emerald: Bradford, UK, 2023; Volume 19, Chapter 11; pp. 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winans, K.; Kendall, A.; Deng, H. The history and current applications of the circular economy concept. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 68, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, R. Silent Spring; Fawcett Publications: Greenwich, UK, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation Research Team. Towards the Circular Economy: Opportunities for the Consumer Goods Sector; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2013; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Bigg, G. After Rio: The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Weather 1993, 48, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, P. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Rev. Eur. Community Int. Environ. Law 1992, 1, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor, S.; Aneja, R.; Madan, S.; Ghimire, M. Kyoto Protocol and Paris Agreement: Transition from Bindings to Pledges – A Review. Millenn. Asia 2024, 15, 690–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, E.; Vijge, M.J. From Millennium to Sustainable Development Goals: Evolving discourses and their reflection in policy coherence for development. Earth Syst. Gov. 2021, 7, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, D. Systematic Review: Opportunities and Barriers to Online Marketing Caused by the Development of the Internet of Things. Bus. Theory Pract. 2024, 25, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konyalıoğl, F.I.; Esen, F.S. (Eds.) Multidisciplinary Approaches to Contemporary Marketing: Digital Trends, Social Issues and Economics, 1st ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gündüzyeli, B. Artificial Intelligence in Digital Marketing Within the Framework of Sustainable Management. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Cervantes, P.A.; Valls Martínez, M.d.C.; Gigauri, I. Sustainable Marketing. In Encyclopedia of Creativity, Invention, Innovation and Entrepreneurship; Carayannis, E.G., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigauri, I.; Apostu, S.A.; Popescu, C. Digital Transformation: Threats and Opportunities for Social Entrepreneurship. In Two Faces of Digital Transformation; Akkaya, B., Tabak, A., Eds.; Emerald Publishing: Leeds, UK, 2023; Chapter 1; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigauri, I.; Martín-Cervantes, P.A. Global trends of digitization in the face of creativity and innovation. Rom. J. Econ. Română De Econ. 2023, 56, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Torres, B.V.; Toro-Espinoza, M.F.; Calderón-Argoti, D.J. El marketing digital: Herramientas y tendencias actuales [Digital marketing: Current tools and trends Marketing digital: Ferramentas e tendências atuais]. Dominio De Las Cienc. 2021, 7, 907–921. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, E.; Shurong, Z.; Ying, D.; Yaqi, M.; Amoah, J.; Egala, S.B. The Effect of Digital Marketing Adoption on SMEs Sustainable Growth: Empirical Evidence from Ghana. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziakis, C.; Vlachopoulou, M. Artificial Intelligence in Digital Marketing: Insights from a Comprehensive Review. Information 2023, 14, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilagavathy, N.; Praveen Kumar, E. Artificial Intelligence on digital Marketing-An overview. Nat. Volatiles Essent. Oils-NVEO 2021, 8, 9895–9908. [Google Scholar]

- Page, S. Digital Neuromarketing: The Psychology of Persuasion in the Digital Age; Neurotriggers: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge, M.; Kitchin, R. Mapping Cyberspace; Routledge: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Erdmann, A.; Arilla, R.; Ponzoa, J.M. Search engine optimization: The long-term strategy of keyword choice. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 144, 650–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, M.; Petersen, J.A. Keyword Selection Strategies in Search Engine Optimization: How Relevant is Relevance? J. Retail. 2021, 97, 746–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. Google ads and the blindspot debate. Media Cult. Soc. 2011, 33, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anupam, V.; Mayer, A.; Nissim, K.; Pinkas, B.; Reiter, M.K. On the security of pay-per-click and other Web advertising schemes. Comput. Netw. 1999, 31, 1091–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinev, T.; Hu, Q.; Yayla, A. Is there an on-line advertisers’ dilemma? A study of click fraud in the pay-per-click model. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2008, 13, 29–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriram, K.V.; Poojary, A.A.; Jawa, V.; Kamath, G.B. Return on investment and return on ad spend at the action level of AIDA using last touch attribution method on digital advertising platforms. Int. J. Internet Mark. Advert. 2022, 17, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Liu, D.; Koehl, A.; Wang, H.; Stavrou, A. Click Fraud Detection on the Advertiser Side. In Proceedings of the Computer Security—ESORICS 2014, Wroclaw, Poland, 7–11 September 2014; Kutyłowski, M., Vaidya, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Jun-Feng, Y.; Xian-Yong, Y. A virtual Cybermarketing System using Web3D and JSR-184. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Artificial Reality and Telexistence—Workshops, ICAT 2006, Hangzhou, China, 29 November–1 December 2006; pp. 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raacke, J.; Bonds-Raacke, J. MySpace and facebook: Applying the uses and gratifications theory to exploring friend-networking sites. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2008, 11, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Salinas, D. Mark Zuckerberg, founder of facebook, at the universidad de Navarra; [Mark Zuckerberg, fundador de facebook, en la universidad de Navarra]. Prof. De La Inf. 2008, 17, 681–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, B.S. Twitter and the library: Thoughts on the syndicated lifestyle. J. Web Librariansh. 2008, 2, 589–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rungta, S. WhatsApp usage differences amongst genders: An exploratory study. Indian J. Mark. 2015, 45, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, D. Moving on from Facebook: Using Instagram to connect with undergraduates and engage in teaching and learning. Coll. Res. Libr. News 2013, 74, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.M.; Nguyen, N.T.; Pham, T.T.X.; Tran, N.H.M.; Cap, N.C.B.; Nguyen, V.K. How ephemeral content marketing fosters brand love and customer engagement. Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2025, ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kerckhove, A. Building brand dialogue with mobile marketing. Young Consum. 2002, 3, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dysart, J. E-mail marketing grows up: A primer for the managed care industry. Manag. Care Interface 2000, 13, 76–78. [Google Scholar]

- Dysart, J. The Internet’s true killer application: E-mail marketing. Instant Small Commer. Print. 2000, 19, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, G.; Wolfram-Hvass, L. Research Methodologies, Data Collection, and Analysis at Mailchimp: A Case Study; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2015; Chapter 10; pp. 170–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, S.; Khatri, S.; Aryal, I.; Devkota, S.; Shrestha, S.; Mahato, S.; Mohammad, M. E-portal design implementation. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Business Information Management Association Conference, IBIMA 2018—Vision 2020: Sustainable Economic Development and Application of Innovation Management from Regional expansion to Global Growth, Seville, Spain, 15–16 November 2018; pp. 4467–4478. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.E.; Malaga, R.A. Exploring the relationship between YouTube video optimisation practices and video rankings for online marketing: A machine learning approach. J. Bus. Anal. 2024, 7, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, V.K. Factors affecting attachment behaviours, cognitive and emotional evaluations on Facebook live streams. Int. J. Web Based Communities 2024, 20, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.E.; Zhang, L. Digital Age Challenge: University Students’ Excessive Use of TikTok. Stud. Media Commun. 2025, 13, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamanna, T. Roles of Brand Image and Effectiveness on Smartphone usage over Digital Marketing. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Information and Communication Technology for Sustainable Development, ICICT4SD 2021—Proceedings, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 27–28 February 2021; pp. 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, J.R. Algorithms in Digital Marketing: Does Smart Personalization Promote a Privacy Paradox? FIIB Bus. Rev. 2024, 13, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghizzawi, M.; Ezmigna, I.; Ezmigna, A.A.R.; Alhawamdeh, Z.M.; Hammouri, M.A.; Alawneh, E.; Al-Gasawneh, J.A. The Big Data Analysis and Digital Marketing. In Opportunities and Risks in AI for Business Development; Alareeni, B., Elgedawy, I., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 2, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghzaiel, K.; Bouzaabia, R.; Hassairi, M. When the Artificial Revolutionizes the Reality: Focus on This New Trend of Virtual Influencers. In Proceedings of the Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing, LNBIP, Milan, Italy, 1–3 July 2025; Volume 531, pp. 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffreys, E.; Xu, J. Celebrity and influencer philanthropy: Debating MrBeast and China. J. Philanthr. Mark. 2024, 29, e1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beers Fägersten, K. The role of swearing in creating an online persona: The case of YouTuber PewDiePie. Discourse Context Media 2017, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkader, O.A. ChatGPT’s influence on customer experience in digital marketing: Investigating the moderating roles. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, Z.K.; Abdelwahed, N.A.A. Developing Consumers’ Experience with Chatgpt Towards Customer Digital Marketing Satisfaction Strategy. Corp. Bus. Strategy Rev. 2024, 5, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlović, N.; Savić, M. The Impact of the ChatGPT Platform on Consumer Experience in Digital Marketing and User Satisfaction. Theor. Pract. Res. Econ. Fields 2024, 15, 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, G.; Mallapaty, S. How China Created AI Model DeepSeek and Shocked the World. 2025. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-00259-0 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- ALIA. The Public AI Infrastructure in Spanish and Co-Official Languages. 2025. Available online: https://alia.gob.es/eng/. (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Wangsa, K.; Karim, S.; Gide, E.; Elkhodr, M. A Systematic Review and Comprehensive Analysis of Pioneering AI Chatbot Models from Education to Healthcare: ChatGPT, Bard, Llama, Ernie and Grok. Future Internet 2024, 16, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, N.; Alén, E.; Losada, N.; Melo, M. Breaking barriers: Unveiling challenges in virtual reality adoption for tourism business managers. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 30, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, N.; Alén, E.; Losada, N.; Melo, M. The adoption of Virtual Reality technologies in the tourism sector: Influences and post-pandemic perspectives. J. Tour. Herit. Serv. Mark. 2024, 10, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Gold, S.; Bocken, N.M.P. A Review and Typology of Circular Economy Business Model Patterns. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 36–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, P.; Sassanelli, C.; Terzi, S. Towards Circular Business Models: A systematic literature review on classification frameworks and archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 236, 117696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano-Pinar, I.; Díaz-Garrido, E.; Bermejo-Olivas, S. Digital transformation for a circular economy: Insights from co-word analysis. J. Technol. Transf. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, G.; de Castro Vila, R.; Dorado, A.; Jäger, A. Circular Economy Adoption in Manufacturing Firms: Evidence From Germany. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 1574–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, G.C.; Tavares, E. Scientific literature analysis on big data and internet of things applications on circular economy: A bibliometric study. Scientometrics 2017, 111, 463–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Põder, E. What Is Wrong With the Current Evaluative Bibliometrics? Front. Res. Metrics Anal. 2022, 6, 824518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Inf. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajovic, I.; Boh Podgornik, B. Bibliometric Analysis of Visualizations in Computer Graphics: A Study. Sage Open 2022, 12, 21582440211071105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, A. Design Thinking: From Bibliometric Analysis to Content Analysis, Current Research Trends, and Future Research Directions. J. Knowl. Econ. 2023, 14, 3097–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadegani, A.A.; Salehi, H.; Yunus, M.M.; Farhadi, H.; Fooladi, M.; Farhadi, M.; Ebrahim, N.A. A Comparison between Two Main Academic Literature Collections: Web of Science and Scopus Databases. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranckutė, R. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The Titans of Bibliographic Information in Today’s Academic World. Publications 2021, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongeon, P.; Paul-Hus, A. The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, J. (Ed.) Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh; Royal Society of Edinburgh: Edinburgh, UK, 1788; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Falagas, M.E.; Pitsouni, E.I.; Malietzis, G.A.; Pappas, G. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: Strengths and weaknesses. FASEB J. 2007, 22, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramko, K.; Jarosch, M. Digital marketing redux: Pharmaceuticals take a second look at e-detailing. J. Med Mark. Device Diagn. Pharm. Mark. 2005, 5, 134–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S.; Tang, T.I. Assessing customer perceptions of website service quality in digital marketing environments. J. End User Comput. 2003, 15, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merisavo, M. The effects of digital marketing on customer relationships. In Managing Business in a Multi-Channel World: Success Factors for E-Business; Saarinen, T., Tinnilä, M., Tseng, A., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2005; Chapter 6; pp. 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuchlik, J. Contribution to the study of neologism. III. Glossolalia & glossographia; [Prolegomena ke studiu neofasií. III. Glosolalie a glosografie]. Ceskoslovenská Psychiatr. 1958, 54, 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- English-Zemke, P. Using Color in Online Marketing Tools. IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun. 1988, 31, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, G.K. International online marketing of foods to US consumers. Int. Mark. Rev. 1997, 14, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, T. Measuring the effectiveness of online marketing. Int. J. Mark. Res. 1999, 41, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R. An internet marketing framework for the World Wide Web (WWW). J. Mark. Manag. 1996, 12, 757–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcht, K.A. Doing business on the Internet: Marketing and security aspects. Inf. Manag. Comput. Secur. 1996, 4, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinen, J. Internet marketing practices. Inf. Manag. Comput. Secur. 1996, 4, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.L.; Coupey, E. Consumer Behavior and Unresolved Regulatory Issues in Electronic Marketing. J. Bus. Res. 1998, 41, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattinson, H.; Brown, L. Chameleons in marketspace: Industry transformation in the new electronic marketing environment. Internet Res. 1996, 6, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, W.; Liu, K. Cybermarketing of the railway transportation enterprise. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Transportation and Traffic Studies (ICTTS 2000), Beijing, China, 31 July–2 August 2000; Wang, K.C.P., Xiao, G., Ji, J., Eds.; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2000; pp. 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, I.; Ionescu-Feleagă, L.; Ionescu, B.Ș. Financial Strategies for Sustainability: Examining the Circular Economy Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, A. Your BibTeX Resource. 2006. Available online: https://www.bibtex.org/ (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Beall, J. Measuring duplicate metadata records in library databases. Libr. Hi Tech News 2010, 27, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M.; Martínez, M.; Gutiérrez-Salcedo, M.; Fujita, H.; Herrera-Viedma, E. 25years at Knowledge-Based Systems: A bibliometric analysis. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2015, 80, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alí Herrera, A. Using Bibexcel with EndNote data; [Usando Bibexcel con datos en EndNote]. ACIMED 2009, 20, 76–79. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, F. Mapping the Knowledge Structure of Image Recognition in Cultural Heritage: A Scientometric Analysis Using CiteSpace, VOSviewer, and Bibliometrix. J. Imaging 2024, 10, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wu, F.; Chiu, Y.R. Advancements and trends in cooperative economy research—A Knowledge Map analysis based on CiteSpace and Bibliometrix. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Cheng, C.; Shen, S.; Yang, S. Comparison of complex network analysis software: Citespace, SCI2 and Gephi. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Big Data Analysis (ICBDA), Beijing, China, 10–12 March 2017; pp. 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.H.H.; Lei, S.; Ali, M.; Doronin, D.; Hussain, S.T. Prosumption: Bibliometric analysis using HistCite and VOSviewer. Kybernetes 2020, 49, 1020–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leydesdorff, L.; Thor, A.; Bornmann, L. Further steps in integrating the platforms of WoS and Scopus: Historiography with HistCite™ and main-path analysis. Prof. De La Inf. 2017, 26, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batagelj, V.; Mrvar, A. Pajek—Analysis and Visualization of Large Networks. In Graph Drawing Software; Jünger, M., Mutzel, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 77–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M.; Lõpez-Herrera, A.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. SciMAT: A new science mapping analysis software tool. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2012, 63, 1609–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.M.; Alpi, K.M. Bibliometric Network Analysis and Visualization for Serials Librarians: An Introduction to Sci2. Ser. Rev. 2017, 43, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Everett, M.G.; Freeman, L.C.; UCINET. Encyclopedia of Social Network Analysis and Mining; Alhajj, R., Rokne, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. VOS: A New Method for Visualizing Similarities Between Objects. In Proceedings of the Advances in Data Analysis, Berlin, Germany, 8–10 March 2006; Decker, R., Lenz, H.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 299–306. [Google Scholar]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicinanza, D.; Buccino, M. A Helicopter View of the Special Issue on Wave Energy Converters. Sustainability 2017, 9, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiatr Borg, S.; Vagn Freytag, P. Helicopter view: An interpersonal relationship sales process framework. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2012, 27, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambridge Dictionary. “Helicopter View”: A General Description or Opinion of a Situation, Rather Than a Detailed One. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/helicopter-view (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Chauhan, N.; Gupta, N.R.; Stephen, A.; Sony, N. A Bibliometric Analysis on Exploring the Emerging Trends and Influence of Green Finance in India Using Bibliometrix. Stud. Syst. Decis. Control 2025, 555, 1177–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Cervantes, P.A.; Valls Martínez, M.d.C. The ingenious gentleman James Gardner March: A retrospective view of his immense works and contributions. Forum Sci. Oeconomia 2022, 10, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serter, M.; Gumusburun Ayalp, G. A Holistic Analysis on Risks of Post-Disaster Reconstruction Using RStudio Bibliometrix. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seglen, P.O. Causal relationship between article citedness and journal impact. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1994, 45, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glänzel, W.; Moed, H.F. Opinion paper: Thoughts and facts on bibliometric indicators. Scientometrics 2013, 96, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotka, A.J. The frequency distribution of scientific productivity. J. Wash. Acad. Sci. 1926, 16, 317–323. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, S.C. Sources of Information on Specific Subjects. Eng. Illus. Wkly. J. 1934, 137, 85–86. [Google Scholar]

- Van Mierlo, T. The 1% rule in four digital health social networks: An observational study. J. Med Internet Res. 2014, 16, e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreopoulou, Z.; Tsekouropoulos, G.; Koliouska, C.; Koutroumanidis, T. Internet marketing for sustainable development and rural tourism. Int. J. Bus. Inf. Syst. 2014, 16, 446–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Lin, M.; Lin, Z.; Xing, B. Running and Chasing—The Competition between Paid Search Marketing and Search Engine Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014; pp. 3110–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J.E. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 16569–16572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egghe, L. Theory and practise of the g-index. Scientometrics 2006, 69, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J.E. Does the h index have predictive power? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19193–19198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhabra, D. Smart Sustainable Marketing of the World Heritage Sites: Teaching New Tricks to Revive Old Brands; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2015; Chapter 13; pp. 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, D. Strategic Marketing in Hospitality and Tourism: Building a ‘SMART’ Online Agenda; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bassamzadeh, N.; Ghanem, R. Multiscale stochastic prediction of electricity demand in smart grids using Bayesian networks. Appl. Energy 2017, 193, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, P.S.; Balaji, M.; Jiang, Y.; Jebarajakirthy, C. Effectiveness of Travel Social Media Influencers: A Case of Eco-Friendly Hotels. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 1138–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S.; Ullah, F.; Shirowzhan, S.; Sepasgozar, S.M.; Lee, C.L. Smart digital marketing capabilities for sustainable property development: A case of Malaysia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Chou, R.J. Rural revitalization of Xiamei: The development experiences of integrating tea tourism with ancient village preservation. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 90, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivars-Baidal, J.A.; Celdrán-Bernabeu, M.A.; Femenia-Serra, F.; Perles-Ribes, J.F.; Giner-Sánchez, D. Measuring the progress of smart destinations: The use of indicators as a management tool. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harries, T.; Rettie, R.; Studley, M.; Burchell, K.; Chambers, S. Is social norms marketing effective?: A case study in domestic electricity consumption. Eur. J. Mark. 2013, 47, 1458–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Martin, F.; Blanco-Gonzalez, A.; Prado-Roman, C. Research challenges in digital marketing: Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitriu, D.; Militaru, G.; Deselnicu, D.C.; Niculescu, A.; Popescu, M.A.M. A perspective over modern SMEs: Managing brand equity, growth and sustainability through digital marketing tools and techniques. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Quismondo, J.; García-Unanue, J.; Burillo, P. Best practices for fitness center business sustainability: A qualitative vision. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, J.; Zioło, M.; Karczmarczyk, A.; Watróbski, J. Towards sustainability in viral marketing with user engaging supporting campaigns. Sustainability 2018, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piras, F. A Systematic Literature Review on Technological Innovation in the Wine Tourism Industry: Insights and Perspectives. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy sets. Inf. Control 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Is there a need for fuzzy logic? Inf. Sci. 2008, 178, 2751–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callon, M.; Courtial, J.P.; Turner, W.A.; Bauin, S. From translations to problematic networks: An introduction to co-word analysis. Soc. Sci. Inf. 1983, 22, 191–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callon, M.; Courtial, J.P.; Laville, F. Co-word analysis as a tool for describing the network of interactions between basic and technological research: The case of polymer chemsitry. Scientometrics 1991, 22, 155–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, H.; Barbosa, B.; Moreira, A.C.; Rodrigues, R. Abandono en servicios-Una revisión bibliométrica. Cuad. De Gestión 2022, 22, 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Searching for intellectual turning points: Progressive knowledge domain visualization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 5303–5310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahlik, T. Comparison of the Maps of Science. Scientometrics 2000, 49, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtial, J.P.; Michelet, B. A coword analysis of scientometrics. Scientometrics 1994, 31, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, N.; Monarch, I.; Konda, S. Software engineering as seen through its research literature: A study in co-word analysis. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1998, 49, 1206–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q. Knowledge Discovery Through Co-Word Analysis. Libr. Trends 1999, 48, 133–159. [Google Scholar]

- Cobo, M.; López-Herrera, A.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. An approach for detecting, quantifying, and visualizing the evolution of a research field: A practical application to the Fuzzy Sets Theory field. J. Inf. 2011, 5, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, P.; Latapy, M. Computing Communities in Large Networks Using Random Walks. In Proceedings of the Computer and Information Sciences—ISCIS 2005, Istanbul, Turkey, 26–28 October 2005; Yolum, P., Güngör, T., Gürgen, F., Özturan, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 284–293. [Google Scholar]

- Parrales Choez, C.G.; Valls Martínez, M.d.C.; Martín-Cervantes, P.A. Longitudinal Study of Credit Union Research: From Credit-Provision to Cooperative Principles, the Urban Economy and Gender Issues. Complexity 2022, 2022, 7593811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]