1. Introduction

Changes in Europe and around the world affect Polish forestry in terms of social expectations concerning various non-productive functions of a forest. Due to market conditions, it is necessary to take a broad perspective in business activity. It is important to manage employees so as to use their skills and potential for the organization in the most effective manner. The organization can function better if the right people are employed, and personnel decisions will affect the company’s activity. Therefore, the appropriate selection of personnel is of strategic significance for the organization [

1]. It is not only the recruitment and selection of employees that matter but also the right distribution of the personnel according to their qualifications and the needs of the organization. Employees can make and implement innovations as well as design long-term changes, thus influencing the development strategy of the company. In consequence, this may result in a competitive advantage [

2].

In recent years, the mission of forest managers has expanded significantly because the forest land area has increased in Europe, especially in highly developed countries [

3]. Currently, forest managers are responsible for improving people’s well-being, guaranteeing local security, and providing economic benefits in many areas of the economy [

4]. However, as some analysts point out, despite the emphasis on people’s well-being, including combating climate change, the increase in the share of forest area causes social costs due to limited local access to land and resources [

5,

6]. Other analysts are concerned about the fact that as forest management institutions need to pursue broader and broader goals they may not be able to ensure forest biodiversity [

7]. Therefore, it seems interesting and desirable to find out what employees of a selected unit of ‘State Forests’ (SF) Holding think of the implementation of the goals set by this organization so as to indicate the influence of SF Holding on the way it is perceived and positioned.

Overview of Reference Publications

The generally accepted theory of human capital assumes that education determines labour productivity. This theory is linked to assumptions about economic policies and the relationship between education, labour, and wages. It is commonly assumed that intellectual development constitutes a form of economic capital for a worker. Education prepares individuals for work, particularly for suitable positions. However, the human capital theory does not stand up to realistic assumptions about specialized occupational groups due to weaknesses in the method for such groups. The use of a single theoretical method to model the human resource management system is due to a failure to identify the work environment and the impact of the work environment on employee behaviour variables. Human capital theory imposes a single linear path on the complex transition between education and work. It does not explain how job position, gender preference, or age and tenure can increase productivity. Wages cannot be the sole indicator of job evaluation or worker status. These limitations have been discussed in numerous studies on social stratification, work, earnings, and education [

8,

9]. Some human capital models attempt to explain the gender pay gap and address its limitations. Human capital theorists are aware of the limitations of these models and are addressing the gender pay gap. There is a small body of research attempting to understand gender differences in employment in certain occupations [

10,

11]. Human capital and advanced technologies can help to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Research findings indicate that green human capital has a positive effect on sustainability. Environmental regulations have a positive impact on the environment. The impact of human capital should be one of the primary goals of sustainability decision-makers and organizations. At the same time, organizations should be aware of the factors that shape human resources and their relative importance. At the same time, organizations should be aware of the factors that influence human resources and their relative importance [

12,

13,

14]. Human capital is an important determinant of environmental performance at company and organizational levels [

15].

The creation of values in an organization begins with leadership. It is leaders who present the goals of an organization, inspire employees, and make a lot of effort to create a friendly work environment [

16]. As a result of these actions, the value is generated not only for the environment, but also for the employees themselves [

17]. The human factor is of key importance to the functioning of every organization. It is people who provide work through their talents, energy, ambition, and creativity. Managers in an enterprise need to select the right tools for the HR policy to effectively make use of the aforementioned elements provided by the staff so as to achieve the goals and successes of the company.

Over the years, the importance of the role of employees has changed a lot. They had a different role during the industrial revolution, when they mostly did hard but technically and conceptually uncomplicated work. Currently, the comprehensive potential of employees is used. This shows that the goals of an organization are not always consistent with the personal goals of employees [

18]. This is an interesting observation due to the fact that the method and degree of implementation of the goals set by the employer translates into the creation of the organization’s value [

12,

19]. Therefore, it is very important to take all actions increasing the commitment of employees. An employee who is committed and aware of the business environment is more willing to cooperate with others and achieves better results. In consequence, work efficiency increases, which translates into better financial results for the entire organization [

20,

21,

22,

23]. Then, employees are passionate about their work and ready to make sacrifices. Thanks to the commitment of the staff, the organization can achieve its goals [

24,

25]. Some researchers stress the fact that the commitment of employees is the effect of their motivation, whereas motivation results in reciprocation of positive actions. Motivated employees, who are treated well by their employer, are more loyal [

26]. As a result of being motivated by managers with external stimuli or being self-motivated with internal stimuli, employees will do the assigned tasks to benefit from their work or to avoid punishment [

27]. Internally motivated employees are determined and ready to make sacrifices to achieve the right effect. They do not need much supervision because they identify with their company. On the other hand, externally motivated employees, i.e., those motivated by the employer, achieve the final effect thanks to rewards, praise, or promotion. These employees achieve effects by pursuing financial benefits or by avoiding negative consequences, such as being reprimanded, deprived of a bonus, or dismissed from work [

28]. Employees can also, to some extent, protect their organization from the negative effects of changes and external turmoil [

29]. Their commitment can be an important predictor of their effectiveness at work and an indicator of their well-being. It is important for employee satisfaction with their job. The commitment of employees can also be perceived as a positive attitude to the company they work for. Committed employees usually appreciate the values promoted by the organization, identify with their work, and have a sense of personal efficacy. The state of commitment can also be understood as the opposite of burnout and the accompanying states of cynicism, emotional exhaustion, and a sense of a lack of achievement. Researchers have noticed that when employers treat their employees better, innovation in the organization increases, which results in its higher rating on the market [

22,

30,

31]. The knowledge, skills, and competences of employees, especially managers, are crucial to finding the causes of errors and problems in the organization. They make it easier to identify and remedy them [

32]. Organizations need appropriate human resources and the right approach to them in order to function properly and compete with each other. The management needs to take care and make appropriate decisions to show a positive attitude towards employees, primarily by the right selection, training, and development of employees, interpersonal relations, and remuneration. These actions should be closely related and consistent [

33].

In view of the role of employees in an organization, the growing position of managers should be emphasized. A manager is supposed to skilfully motivate employees. This directly affects the technical skills of employees, resources related to social relations (including bonds with the environment), and intellectual resources (useful information in the decision-making process, e.g., knowledge, know-how, patents, copyrights, developed and implemented standards of quality, environmental protection, and the policy of corporate social responsibility) [

34]. Skilful motivation of employees affects the manager’s attitude to the tasks entrusted to them [

35]. Employees are willing to make an effort and achieve the appropriate level of their performance [

36]. Therefore, in order to increase work efficiency in an organization it is important to create a fair and transparent employee evaluation system [

37].

By observing the market, it is possible to see how much the approach of company managers to the problems of human resources management has changed. If companies want to be successful on the market, they must treat the human factor from the point of view of the potential resource rather than as a quantitative resource, as has been so far. According to Ulrich [

38], this shift in the perception of human capital has occurred in recent years. Traditionally, in the context of labour and business functions, human resources were viewed within an organization as a cost to be minimized. Today, however, they are seen as an asset that adds value to the organization. Entrepreneurs invest in human capital because they recognize its potential to add value to the company [

39]. Wuttaphan [

40] argues that further research into human capital is required to show how it affects the performance of different sectors of the economy and its potential to promote employee engagement. Therefore, the aim of our study was to analyse and assess the degree of employees’ commitment to work. Now, it is known that the manager must have not only technical but also social skills as they significantly facilitate cooperation and influence interpersonal relations. These skills shape the team and influence the atmosphere at work [

41]. In consequence, employees are satisfied with their jobs, committed to work hard, and loyal to the company.

2. Materials and Methods

Our study was based on the preliminary analysis of available reference publications and a diagnostic survey. Respondents employed in forestry were surveyed with an original questionnaire with the Likert scale, which enabled the presentation of their diverse attitudes towards work. Thanks to the categorized statements, it was possible to determine the respondents’ predilections (special preferences) and to indicate their tendency to select areas specified in the survey. This enabled a more comprehensive evaluation of the population under analysis. The data obtained from the analysis of the survey questionnaire are measured according to the Likert scale. As indicated in the methodology, it takes values from 1 to 5. Since it is an ordinal variable, non-parametric tests were used to analyze it. Intentionally, the transformation of the original data was not applied in order to fully reflect its importance in the process of evaluating employee involvement in the studied forestry organization.

The Regional Directorate of the ‘State Forests’ National Forest Holding in Piła consented to sharing the survey among the employees. The aim of the survey was to obtain information about the degree of the employees’ satisfaction with their jobs and their commitment. The survey indirectly indicated the state of compliance with and protection of employee rights. It also showed how effectively human resources in the supervised units were managed. The questionnaires were sent to all the staff of the units supervised by the Regional Directorate in Piła, as well as the staff of the Directorate itself. Participation in the survey was voluntary. The questionnaire consisted of two parts, i.e., the degree of the employees’ satisfaction with their jobs and their commitment.

Human capital theory spans a number of industries and disciplines, particularly economics and sociology. Although the theory has been criticized, it continues to influence research disciplines. Specialized industries play a particular role in the application of human capital theory in this area. One such group of specific sociological areas is the field of forestry labour. To address this gap and organize the impact factors of selected sociological areas on forestry employment in a systematic way, this article assesses human capital from four comprehensive perspectives, focusing on the theory’s methodological, empirical, and practical aspects. To ensure a clear and factual analysis, this paper uses an impact assessment of selected sociological factors based on a real-world study. This allows the specific theories of capital to be illustrated and compared with the results presented in the general literature, including new studies. This study assesses the key elements of local development goals, risks, and barriers, and the basic capital necessary for forest management. The analysis presented here is original in its consideration of state organizational conditions and provides new data on the management principles of the human resources responsible for forest management. However, divergent groups of forest workers in Europe and around the world may be a factor. This will facilitate mutual understanding and prepare the ground for economists to discuss forest management. Conflicting views highlight the need to evaluate existing theories on resource management [

42,

43].

The Department of Organisation and Personnel of the Regional Directorate of ‘State Forests’ National Forest Holding supervised the implementation of tasks related to the staff survey. In 2022, 774 respondents were surveyed—514 men and 260 women. At the end of 2022, the State Forests employed 25,877 people. In 2023, there was an increase of 138 people compared to 2022. In 2021, the average monthly employment was 25,520 people. The research is on a representative group for the State Forests in Poland [

44]. Human capital has been defined as a human resource that allows for the fulfilment of the basic tasks of an organization such as the State Forests in the example of a selected Regional Directorate in Poland. This provides a case study element for the assessment of employee involvement in the realization of tasks adopted by an organization implementing the European Forest Policy.

The survey used ten questions, which were analyzed using the Likert scale. Each of the areas listed above was assigned statements which the respondents replied to. The answers were ranked as follows: 0—I totally disagree; 1—I partly disagree; 2—It’s hard to say/It depends; 3—I partly agree; 4—I totally agree.

They were recorded for the following categories of questions:

AD1. Bond with the company,

AD2. Identification with the company,

AD3. Sense of responsibility for work,

AD4. Readiness to make sacrifices,

AD5. Interest in work,

AD6. Commitment to work,

AD7. Sense of effectiveness,

AD8. Focus on company development,

AD9. Pride in working for the company,

AD10. Focus on results.

The analysis of the research results was used to verify the research hypotheses. The following four separate hypotheses were proposed regarding the factors influencing employee commitment to the state forest:

H1. The gender factor affects the ‘State Forests’ employees’ commitment to work,

H2. The age factor significantly affects the ‘State Forests’ employees’ commitment to work,

H3. The length-of-service factor affects the ‘State Forests’ employees’ commitment to work,

H4. The place-of-work factor affects the ‘State Forests’ employees’ commitment to work.

Sustainability of an organization is achieved through the involvement of its employees. An indication of how such commitment changes and whether it is influenced by age, length of service, gender, or position held indicates whether the organization is able to meet its objectives within the European Union.

The results of the survey were analyzed statistically for two groups with the Mann–Whitney U test. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used for a larger number of factors. The level of statistical significance was assumed as α = 0.05. The Statistica 13 software (StatSoft, Kraków, Poland) was used for all calculations.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the results of the questionnaire surveys conducted in the selected organizational structure of the ‘State Forests’ Holding (Regional Directorate of the ‘State Forests’ Holding) in Piła. The responses ranked 0–5 showed a definite tendency to partial agreement with the following questions included in tests, AD2, AD3, AD4, AD5, AD9, and AD10. The respondents totally agreed with the questions in test AD6. There was a weak dominance in test AD1 and a supplementation of the results in test AD10. The respondents’ choices in test AD8 (35%) were inconclusive.

Table 2 shows the testing of hypothesis H1, which says that the gender factor affects the ‘State Forests’ employees’ commitment to work. This hypothesis was verified by assessing the significance of men’s and women’s responses.

There were significant gender-dependent differences in the respondents’ answers to questions AD3 and AD6. In both cases, men gave higher scores.

Figure 1 shows the testing of the statistical hypotheses for the cases where a particular gender characteristic significantly affected the responses provided to individual questions. Both the men and the women declared that they were significantly focused on the tasks assigned by their superiors. They also pointed to the influence of the effectiveness of these tasks on the organization.

The indicator of the influence of work on the results, efficiency, and development of the company proved to be significant. The female respondents rated the importance of their commitment to work lower than the male respondents. Both the men and women declared a similarly high level of concentration on tasks assigned to them. The results were significant.

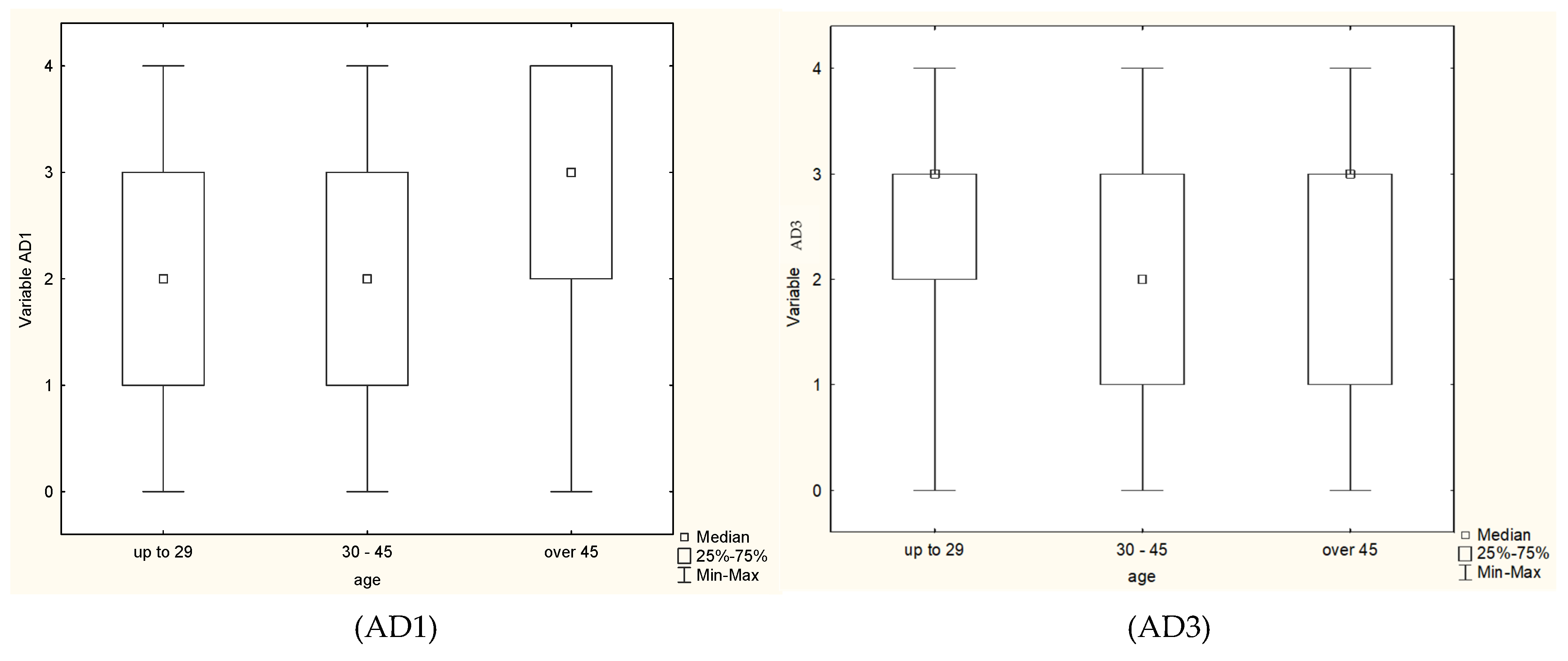

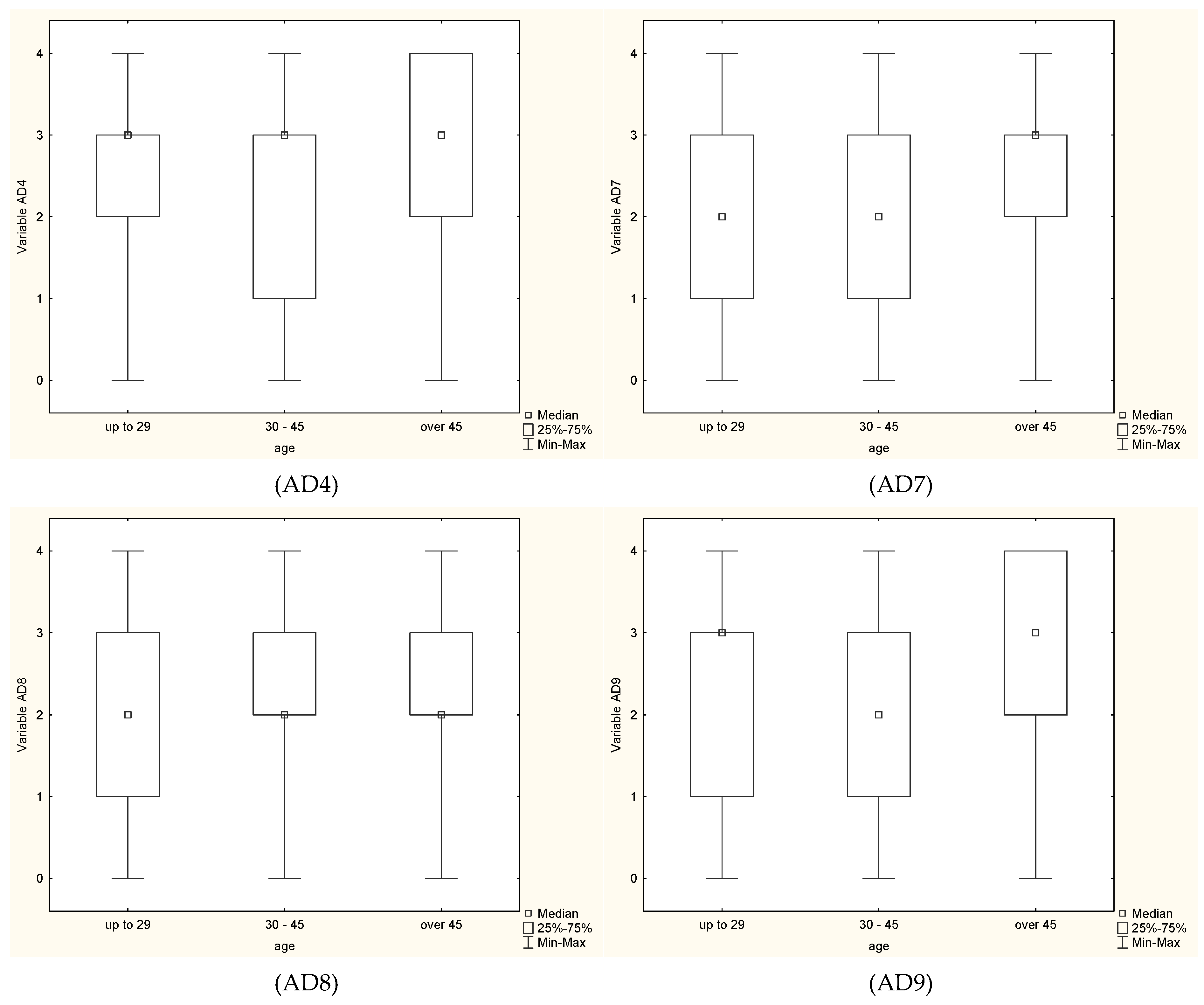

Table 3 shows the significance levels for the responses obtained in the Kruskal–Wallis test vs. the respondents’ age. In the A1-H2 test, the respondents aged 30–45 differed in the values of their responses from those aged over 45. Similarly, there were statistically significant differences between the same age groups of respondents in the AD3 and AD4 tests. In the AD7 test, there were no differences in the responses provided only by the respondents aged under 45. In the AD8 test, the responses provided by people aged under 30 were different from those given by the other age groups. In the AD9 test, the 30–45 age group had a different opinion from the younger and older respondents.

The test of hypothesis H2 concerning the influence of age on employees’ commitment revealed significant differences in the assessment of employees’ commitment and their willingness to devote free time. There were also significant differences in their sense of influence on the course of work as a result of participation in the activities of the company and in their perception of distinction due to the work performed.

All significant analyses are shown in the graphs in

Figure 2. They are an illustration of the respondents’ opinions. The vertical axis shows the values of the responses to questions AD1–AD10.

The next group of questions (

Table 4) subjected to the Kruskal–Wallis test was the influence of employees’ length of service on their commitment to work for the ‘State Forests’ Holding—H3. The results of test A1 revealed significant differences between the employees whose length of service was 8–15 years and those employed for more than 15 years. There were similar significant differences in the responses given in test A4. In test A9, there were significant differences in the responses provided by the employees with a length of service 8–15 years, those employed for over 15 years, as well as younger employees working for less than 2 years. The other responses did not differ significantly from each other.

The assessment of the length of service showed significant differences in the employees’ sense of willingness to stay with the company, their sense of distinction at work, and their devotion of private time to work (

Figure 3).

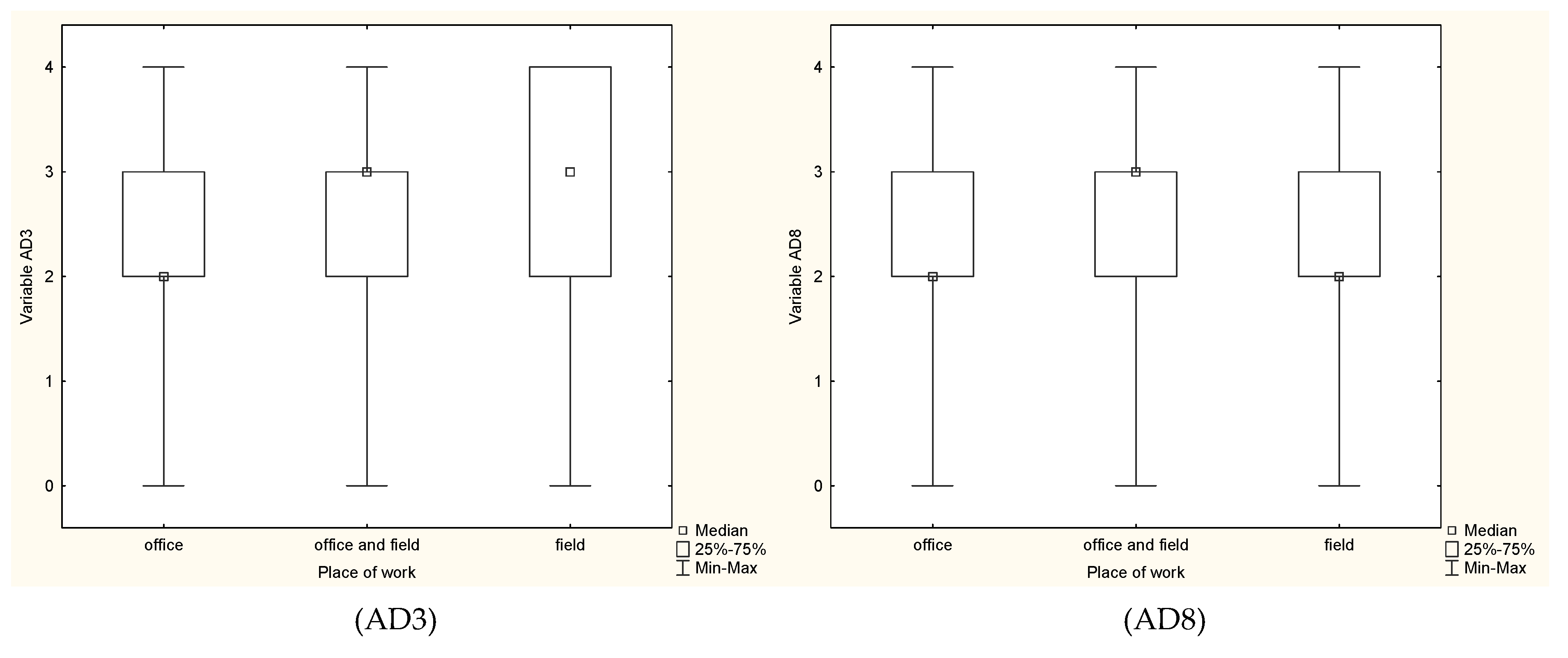

Table 5 shows the testing of hypothesis H4, according to which the place-of-work factor significantly affects the ‘State Forests’ employees’ commitment to work. The significance value of the responses for multiple comparisons described with the Kruskal–Wallis test revealed a convergent level of ratings in most test questions. The exceptions were AD3, where the responses given by the office staff differed from those provided by the field workers, and AD8, where the staff working both in offices and in the field gave different responses than the field workers.

The assessment of the indicators of the influence of the place of work showed that there was a significant difference only in the assessment of the influence of work on the company’s business activity and in the confirmation of questions AD3 and AD8 (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

The questionnaire survey showed that in the context of the ten-component scale, the most common responses were I totally agree, I partly agree, and It’s hard to say/It depends. The share of the negative and neutral responses was comparable in most of the areas under analysis, except for the interest in work and absorption in work (questions AD5 and AD6), where it was the smallest.

The respondents who chose the options I partly agree and I totally agree when referring to their bond with the company (AD1) declared strong attachment to their employer. They thought it would be difficult for them to leave the company. They have no intention of changing their jobs and they see their future in their current company. By contrast, the respondents who gave negative answers showed that they did not feel particularly attached to the company. They are thinking of changing their jobs and if they had the opportunity, they would gladly consider it. Various studies have indicated that the overall functional state of the body, stress, and work capacity, are linked to psychosocial factors at work. The overall state of engagement of forestry workers is influenced by factors related to work content, intensity, and the organization [

45].

The respondents who identified with the company and felt part of it (AD2) gave positive answers. They respect the standards applied by the company and believe that both the goals pursued by the company and the tasks they do are important. Negative answers showed the respondents’ lack of identification with the company. These employees do not respect the current rules in the company, nor do they consider their work and the company’s goals to be important. Forests are of great importance to sustainable development because of their ongoing contribution to biodiversity conservation. The involvement of employees in the organization’s activities determines the level to which the forest bioeconomy contributes to the country’s social and economic development. The organization influences people’s livelihoods and contributes to the country’s economic development. However, the role of the forester’s work is affected by the challenges of organizational policy and the reduction in man-made changes. Employee involvement can increase the benefits of forests through the sustainable exploitation of forest wealth [

46].

The respondents who gave positive answers to the questions about the sense of responsibility for their work (AD3) considered their jobs important for the functioning and improved effectiveness of the company. They conscientiously do the assigned tasks. On the other hand, the negative answers showed that the employees did not find their work important for the company. They do not think their work affects the company’s results, so they do not always do their duties with due care. Based on the literature, it has been confirmed that good management can increase labour resources. Through labour development, it is possible to support employees’ abilities and commitment in the face of the pressures of change associated with a competitive environment and new forms of work [

47].

As far as commitment and readiness to make sacrifices is concerned (AD4), the respondents who gave positive answers were willing to make more commitments for the company than is formally required. They are ready to devote some of their free time to work. If necessary, they are willing to participate in the costs in order to support the company. Negative answers showed the lack of commitment. Those employees often made less effort at work than their duties required. In the event of difficulties, the company could not count on their support if it involved some sacrifices or the need to devote their free time. Such an example is the Scandinavian countries, considered pioneers in environmental policy, which are among the world leaders in terms of their willingness to make economic sacrifices for environmental attitudes and behaviours. Verified insights provide a deeper understanding of people’s willingness and link to appropriate attitudes and behaviours beneficial to the acceptance of existing forest environmental policies [

48].

The respondents who gave positive answers to question (AD5) showed their high interest in work. These employees like their jobs and enjoy performing their tasks because they find them interesting. They perceive work as a value in itself—greater than the money they earn for performing it. Negative answers meant the respondents were not enthusiastic about performing their duties and not interested in work. They do not enjoy performing their jobs, which they treat only as a source of income. Positive responses to the commitment-to-work component (AD6) showed the employees’ dedication to their work and their concern about the good condition of the company. They think that they are adequately focused when performing their duties. Negative responses were provided by those who do not focus on the instructions given by their superiors and the tasks assigned to them at work. These employees showed that they did not make much effort for the company, nor did they adequately focus on the tasks at work. The problem is job insecurity, which has a negative impact on job satisfaction. The conclusion of the literature research should be taken seriously by organizations creating a productive environment while striving for sustainable development [

49].

The respondents who gave positive answers to the question about effectiveness at work (AD7) believed they were competent professionals who could effectively do their jobs. They feel that their work has a significant influence on the company and believe that they can cope with difficult situations. On the other hand, negative answers were given by the respondents who did not think that their work had a positive influence on the results of the company. They have doubts about their skills and the ability to cope with challenges. They do not believe that their work is a significant value for the company. The results obtained in a study [

50] on economic efficiency indicate long-term sustainability and increased economic efficiency of forestry enterprises can be achieved by improving forest management principles and investing in research and development activities.

The respondents’ positive answers to the question asking for their opinions on ‘focus on company development’ (AD8) showed their engagement in activities aimed at improving the quality of their work. These employees want to improve their qualifications for the development of the company. By contrast, the negative responses showed that the employees did not find it necessary to improve their qualifications nor did they see the need to introduce improvements in the company [

30,

43].

The respondents who gave positive answers to the ‘pride in working for the company’ component (AD9) highly valued the opportunity to work there and considered it prestigious. They treat their work and dedication for the company as a distinction. Their achievements at work are a reason for personal satisfaction. In contrast, the respondents who gave negative answers did not take pride in belonging to the company nor were they satisfied with their jobs. Based on a review of the literature and practice-based knowledge, the important role of commitment and pride in one’s profession in timber production and forest management is indicated. For men, the prestige associated with the job and the economic benefits are much more important than our study suggests [

51].

The respondents who gave positive answers to the ‘focus on the results’ component (AD10) showed that it was very important for them to work effectively and efficiently so as to bring the greatest possible benefits to the company. Both the achievement of the company’s goals and personal achievements are very important for them. On the other hand, the negative responses showed that the employees did not try to be more effective. They are not interested in achieving the goals set by the company [

1,

2]. Forestry and forest management may receive capital for sustainable development due to the importance of the protective function of the forest (protection of biodiversity). However, these processes will come at the expense of production and numerous social functions [

52].

Every organization uses various aspects of human activity. As a result of the influence of environmental factors, it undergoes numerous transformations. Consequently, managers need to constantly supervise it and make decisions. The establishment of the right relationships and building a long-lasting, engaging relationship between the company and employees should be based on mutual trust. The management should strengthen the employees’ feeling that the company is successful because of the positive attitude and commitment of the staff. The role of employees in the company is emphasized both in the relational approach and in the behavioural theory of companies, according to which the assessment of the benefits employees gain by performing their duties influences their motivation to work [

53].

The results of hypotheses H1 and H2 have marginal impact for further analysis. The values are sufficiently weak that the hypotheses require further research. In our case, we believe they would not be sustained. Hypothesis H2 regarding the effect of employee age on job commitment was confirmed. This is indicated by significant differences in respondents’ answers to questions AD1, AD2, AD4, AD7, AD8, and AD9 (p > 0.1). Hypothesis H3 regarding the effect of seniority on work commitment of employees of the National Forest Service was confirmed within the framework of significant differences for the obtained answers of respondents to questions AD1, AD4, and AD9 (p > 0.1).

Work engagement, defined as a positive and satisfying work-related state, has been confirmed in other studies for pain management and in other professions. High levels of engagement are associated with better organizational performance and a stronger sense of belonging among employees [

54,

55].

Hypothesis H1 regarding the influence of gender on job commitment of National Forestry employees was rejected, with only two significant differences confirmed for sense of responsibility AD3 (

p > 0.02) and job commitment AD6 (

p > 0.03). Hypothesis H4 regarding the influence of workplace on the commitment of “National Forest” employees was rejected, with only two significant differences confirmed in terms of sense of responsibility AD3 (

p > 0.1) and company development AD8 (

p = 0.1). In line with models for other companies besides forestry, work engagement was directly influenced by job position. Office workers showed higher work engagement than production workers. The results of this study underscore the differences in the perceptions of work and the work environment for employees in forestry. However, this requires ensuring sustained job satisfaction [

56]. There is ongoing interest in how important forests are to employment and what measures need to be taken to reduce decent work deficits. This study is a contribution to the existing debate on the scope of employment, with a particular focus on the forestry and logging subsector. Estimates of the lack of significant differences for employment regardless of gender and occupation confirm the shift away from the differentiation of these problems, which has not yet been addressed in official statistics and literature. The results obtained are aggregated with the latest official data to provide a partial overview related to global forestry employment. Gender is considered in most publications to be one of the most important factors determining access to and control over forests. It has been confirmed that when women have equal access to work in forests, better job security results can be achieved [

57,

58,

59,

60,

61].

The human resources used by an organization to carry out tasks related to the sustainable development of forestry are constantly changing. This is influenced by changes in the organization’s tasks and various aspects of human activity. Forestry in Europe and around the world is undergoing numerous transformations. This is due to the impact of environmental factors, resulting in the need for constant supervision and decision-making by managers. The formation of positive relationships and the development of a sustainable team of employees within the company should be based on management reinforcing the idea that the employee, through their attitude and commitment, affects the implementation of social tasks. The danger lies in a mismatch between positions and the employee’s predisposition, as well as a change in the role the employee plays in the company. Generational changes emphasize a relational approach, a behavioural theory of companies, and a change in the evaluation of the role of the employee and the benefits that will be brought to the employee by performing job duties. The variability of expectations and the employee’s role can affect their motivation to work.

5. Conclusions

The analysis of the results of the research on the role of human capital revealed the significance of differences in the research hypotheses. However, significance was found in the excluded elements of the questionnaire survey.

Hypothesis H1 regarding the influence of gender influences on the commitment of “National Forest” employees to work was rejected, where there were only two significant differences confirmed in terms of a sense of responsibility and commitment to work.

Hypothesis H4 indicating how workplaces affect employees’ commitment to the Forest Service was rejected, where there were only two significant differences confirmed in terms of a sense of responsibility and company development.

The proportion of neutral responses was similar in most of the areas analyzed. Most respondents also reported a strong attachment to their employer. Identification with the company and its objectives played an important role. When asked if they felt responsible for their work, the responses were mostly positive. Employees believe that their work is important for the functioning of the company and for improving its efficiency. On the other hand, negative responses to the survey questions indicate that employees are not concerned about the evaluation of their company’s performance. Sustainability in forestry should be understood also in terms of the internal environment and concern for each employee. According to the results, socio-demographic factors influenced forest management [

62].

Hypothesis H2 of the effect of employee age on work engagement was confirmed. Hypothesis H3 of the effect of seniority on work engagement of state forest employees was also confirmed. As an organization, the State Forestry Company uses human resources as a manifestation of human activity. The labour market is ripe for change due to the influence of environmental factors and decisions made by managers. Building relationships with employees and creating a long-term bond between employees and the company should be based on knowledge of the factors that influence these relationships, such as the seniority and age of a group of employees. Indicated efforts to halt deforestation and promote forest conservation require youth involvement in the protection of forest resources. It is important to identify the importance of gender in managing and implementing sustainable forest management and is related to gender and socioeconomic factors, especially education [

63].

The results of hypotheses H1 and H2 have marginal impact for further analysis. The values are sufficiently weak that these hypotheses further research. In our case, we believe that they were not maintained by them. Similar results outside of Europe show that an employee’s role in a company can be differentiated by their gender and location. It is important that employees in the course of their work are able to assess the relational benefits they derive from belonging to an organization and performing their duties regardless of their gender or position. Gender diversity on the job is associated with higher employee well-being.

_Li.png)