Abstract

This study examines the impact of cooperative development levels and collaboration models on social network relations in İzmir, Türkiye. The research aims to uncover how the developmental stages of cooperatives affect their relational positions and the structural configurations within the network. Empirical data were collected through semi-structured, in-depth interviews with key stakeholders. A mixed-methods design, integrating thematic content analysis with social network analysis (SNA), was employed. Development levels were evaluated based on entrepreneurial orientation and innovativeness. Sociometric data validity was enhanced through cross-validation of actor-reported ties. The SNA identified actor clusters, relationship intensities, and positional configurations within the network. Results indicate that cooperatives at advanced development stages are significantly more active in entrepreneurial and innovative initiatives and exhibit a greater degree of centrality, form denser clusters, and occupy structurally prominent positions. Finally, the results reveal that the adopted model of collaboration directly influences both the structure and quality of network relationships and that there is a significant correlation between cooperation strategies and network centrality. Although the study is limited to a focused sample of 15 local actors, including six cooperatives, and thus restricts generalizability, it provides valuable insights into the micro-dynamics of cooperative networks within localized agricultural contexts.

1. Introduction

Since the final quarter of the 20th century, regional policy approaches have increasingly focused on enhancing the competitive potential of settlements by promoting entrepreneurship, innovation, localized knowledge flows, and network structures. These policies have evolved to promote not only cooperation among firms but also collaboration between firms, local governments, civil society organizations, and other regional actors—forming complex networks centered on innovation and inter-institutional relationships [1] (pp. 14–17). Cooperatives, once key tools of regional development in the 1960s, have regained their role as important institutional actors in recent regional policy frameworks. By facilitating local participation in economic activities, promoting sustainable business models, and strengthening social capital, cooperatives present a solidarity-based alternative to conventional market structures [2,3,4]. Their effectiveness and sustainability are shaped not only by their internal governance but also by external networks and relational configurations [5,6,7]. The relationships between actors and the structural configuration of networks have become increasingly important both for the evolution of cooperatives as proactive agents and for the achievement of locally driven regional development [8,9,10]. Recent work on signed social networks with dynamic opinion updates [11,12] emphasizes that the structural configuration of relational ties significantly influences system-wide outcomes, whether related to consensus formation or organizational dynamics. Building on this network-based understanding, this study examines how the structure of cooperative networks relates to organizational development and innovation capacity. While much of the existing research has focused on opinion dynamics within signed networks, this study extends the network-based perspective to the analysis of real-world cooperative networks, emphasizing their role in shaping organizational development trajectories and innovation potential. By focusing on empirical cooperative networks operating within regional development frameworks, this research addresses an important gap by exploring how structural features, such as actor centrality and collaboration models, influence cooperatives’ organizational growth and integration into broader governance networks.

A network is generally defined as a set of nodes (e.g., organizations) and the ties that signify the existence or absence of relationships among them [13]. Networks are dynamic in nature, shaped through connections formed out of necessity or mutual agreement among actors [14]. Inter-organizational linkages facilitate access to key resources embedded in the network, such as information, technological innovation, financial capital, and social capital. Accordingly, networks provide strategic advantages by improving organizations’ access to critical resources [15,16]. For cooperatives operating as economic entities, network relations offer numerous benefits: lowering production costs, enabling collective purchasing and bargaining power, sharing the financial burden of innovation, fostering financial intermediation, mitigating risks through insurance mechanisms, and facilitating the coordination and development of marketing strategies. These benefits significantly contribute to achieving sustainable development and strengthening the economic resilience of cooperatives [17].

In order to provide these benefits, actors adopt various strategies to establish connections and integrate themselves into the network structure [18]. One such strategy involves the use of cooperation mechanisms. Cooperation encourages innovation by enhancing trust-building, facilitating negotiation processes, and promoting the exchange of resources among actors [19,20]. Due to this bonding-oriented structure, cooperation-based relationships are more likely to evolve into resilient and sustainable systems [21]. Within regional development policies, cooperation remains a key implementation tool. The primary supporters of regional development initiatives are funding institutions that channel economic resources into the region and central and local government units that promote local–regional cooperation [22,23]. Particularly, local governments are critical in structuring regional cooperation networks.

In Türkiye, the development of agricultural cooperatives has historically been shaped by efforts to support small-scale farmers, modernize agriculture, and promote rural development. Initially, the state prioritized establishing Agricultural Credit Cooperatives to facilitate farmers’ financial access [24]. Later, Agricultural Sales Cooperatives were promoted to support the marketing of agricultural products [25]. During the planned economy period (1960–1980), cooperatives were actively promoted as instruments for agricultural development [26,27]. The adoption of neoliberal economic policies in the 1980s reduced agricultural subsidies, creating financial challenges for cooperatives [28]. With the transition to the “Last Period” of the Turkey–European Union Partnership Relations in the late 1990s, cooperatives once again received support through the EU harmonization process and participated in rural development projects. This support has continued under various development projects. The support available to cooperatives has come through centrally administered agricultural support and rural development projects. In 2012, municipalities were granted the authority to implement all forms of activities and services supporting agriculture and animal husbandry [29]. This legal change enabled cooperatives to benefit from local government support and strengthen their role in local development. At this juncture, İzmir Metropolitan Municipality (IMM) became the first local authority in Türkiye to establish a specialized agricultural services department and to implement pioneering projects in local development [30] (p. 160). IMM supports producers through two channels: direct income-generating and educational support to small-scale farmers and support through producer organizations such as cooperatives [31]. IMM’s cooperative-centered agricultural support initiatives began in 2004. Developed through product-based guaranteed contracts, IMM’s collaboration model has emerged as a flagship example in Türkiye. Besides aligning with IMM’s local development agenda, this model has offered several advantages to cooperatives, including increased producer visibility, the reinforcement of cultural identity, stronger trust-based relationships with consumers, and improved knowledge and experience in commercial and bureaucratic fields [32] (p. 43). Moreover, this model has enabled cooperatives to integrate into the public food procurement chain and become embedded in the local network structure. Given the diversity of local characteristics, no single network structure or development model is applicable across all regions in Türkiye. However, successful local policies aligned with national goals offer adaptable cooperation models for diverse local contexts.

Building on this context, examining the impact of collaboration and network structures across different localities becomes a significant research focus. This article focuses on the effects of the same collaboration model within a shared network structure on different agricultural development cooperatives. Specifically, the study examines the effects of the purchase guarantee collaboration between IMM and cooperatives and the structural characteristics of the local actor-network. The network analysis of the İzmir case contributes to understanding the configuration of cooperation among local actors, identifying the network patterns shaped by regional interactions, and developing strategies to foster coordination among stakeholders. Accordingly, the study analyzes how the development levels of cooperatives and their collaboration models influence their network structures. The research addresses the following key questions:

- What is the relationship between the development levels of cooperatives and their network relations?

- Do the development levels of cooperatives affect their network positions?

- How do collaboration models shape network relations?

The study employs thematic content analysis and social network analysis methodologies to explore fundamental network dynamics, such as collaboration and development levels. In the thematic content analysis, the development levels of cooperatives and regions (basins) were assessed using innovation and entrepreneurship indicators. Sociometric data were cross-validated through actor confirmations during the thematic content analysis process. Social network analysis revealed the relational ties among cooperatives, clustering patterns, and the overall network structure.

Within cooperative studies, this research offers significant insights into the organizational development processes of cooperatives, emphasizing their roles as innovative and entrepreneurial actors. In the social network literature, the research contributes by examining how organizational innovation capacity and collaboration models shape network configurations.

The research examines how actor relations are shaped through cooperatives in the İzmir case and how the collaboration model affects the network structure. The findings aim to stimulate new discussions on cooperative organization within regional development policies and the formation of local stakeholder clusters. Additionally, the study offers practical implications for building successful collaborations among local economic actors. The article is structured as follows: Section 2 offers a comprehensive description of the research sample, methodology, and data sources and elaborates on the study’s limitations and unique contributions; Section 3 presents the social network analysis findings; Section 4 discusses these findings in relation to the existing literature; and Section 5 summarizes the conclusions of the study.

2. Study Area, Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

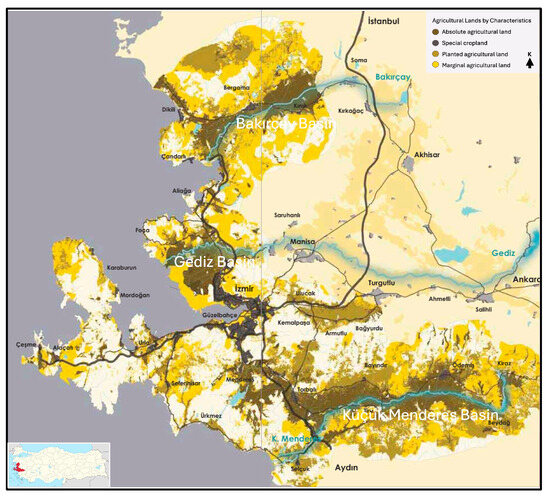

The study’s sample is İzmir Province, located in western Turkey. The primary reasons for selecting İzmir as the sample include fertile agricultural land density, its high agricultural production potential, the advanced level of agricultural organization, and the well-developed cooperation between the İzmir Metropolitan Municipality (IMM) and agricultural cooperatives. The province’s fertile agricultural lands are predominantly concentrated in the Bakırçay, Gediz, and Küçük Menderes River basins (Figure 1). The Bakırçay Basin (BB) and Küçük Menderes Basin (KMB) are located to the north and south of the İzmir metropolitan area, respectively, and form agricultural corridors where prime agricultural lands are concentrated.

Figure 1.

Agricultural lands by characteristics in İzmir [33].

In İzmir, the number of agricultural production and agricultural development cooperatives is concentrated in these basins. A total of 56% of the agricultural development cooperatives in İzmir are located within these regions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of agricultural development cooperatives (ADCs) in İzmir are located within the BB and KMB [34,35].

The total number of producer organizations with which the IMM signed purchase guarantee contracts in 2021 is 28. Of these, 2 are producer unions operating across the Izmir region, 3 are production cooperatives, and 23 are agricultural development cooperatives [36]. Cooperatives in the KMB are more developed compared to those in the BB. The IMM initiated its first collaborations aimed at fostering local development with cooperatives located in the KMB [37] (p. 44). IMM’s approach to establishing direct partnerships with cooperatives varies by basin. The way IMM establishes direct relationships varies by basin. In this context, it should be noted that in the KMB, IMM engages directly with the cooperatives, while in the Bakırçay Basin, it establishes relationships through the cooperatives’ umbrella organization named İzmir KÖYKOOP. This collaboration involves the integration of cooperatives into the public food supply chain through the municipality’s contractual procurement from cooperatives. In this context, the actor sample of the study consists of cooperatives operating in the KMB and BB that have contractual procurement agreements with the municipality. A total of six cooperatives—three from each basin—are analyzed within the scope of this study. The cooperatives included in the sample have implemented pioneering projects in their localities and possess a well-developed entrepreneurial structure.

2.2. Materials and Methods

The data sources used in the study consist of transcriptions of in-depth interview notes and the actor-network sociomatrix recorded at the end of the interviews. The data used in the study was obtained through semi-structured in-depth interviews conducted during field research carried out at two different times: between 29 July–1 August 2019 and 25 June–6 July 2022. In this context, a total of seven local government units, two Cooperative Unions, and six agricultural development cooperatives were interviewed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Details of interviewed actors and duration.

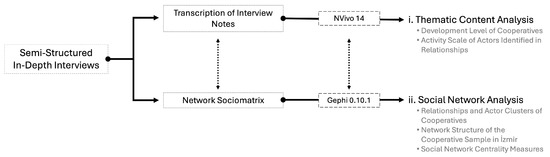

The framework for the semi-structured, in-depth interviews conducted with cooperatives and local governments is included in Appendix A (Table A1 and Table A2). The framework questions generally pertain to the structure of local development, the agricultural sector, cooperative activities, and production organization. Similar framework questions were formulated in interviews with local governments to evaluate the same dynamics. This approach aimed to test the reliability of the information obtained from the cooperatives and to enable cross-verification. The research methodology includes semi-structured in-depth interviews, thematic content analysis, and network analysis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the research methodology.

The data obtained from the in-depth interviews relate to the institutional structure of the cooperatives, their development dynamics, and actor interactions, as well as dimensions such as innovation, entrepreneurship, competitiveness, governance, and institutional and relational path dependency.

A thematic content analysis was conducted using NVivo 14. software, based on the transcription of interview notes. This analysis aimed to identify the development levels of the cooperatives as well as the scale of influence of the actors they interact with. To ensure data consistency, findings related to the actors’ scales of influence were cross-checked against the results of the network analysis.

Network-based research focuses primarily on the structure formed by inter-actor relationships rather than on the individual characteristics of the actors themselves. Accordingly, once an actor is identified, all related actors are included in the network, and the resulting interaction pattern is treated as sociometric data [38]. The actor-network sociomatrix includes the depth and types of relationships among local actors and serves as the primary data set for the social network analysis. The mathematical calculations and visualizations of the network sociomatrix obtained from the interviews were performed using Gephi 0.10.1 software. In the final phase of the interviews, participants were asked to evaluate the actors they engaged with by scoring the type and depth of each relationship. This process produced an actor sociomatrix. To validate the actor-network sociomatrix, each participant was asked additional questions during the interview regarding the actors they relate to, the type of relationship, and the degree of interaction. These details were transcribed into the interview notes. To enhance the reliability of the sociomatrix data, this cross-verification method was employed. Moreover, actors mentioned during the interview—even if not explicitly included in the final relationship patterns—were incorporated into the sociomatrix.

2.2.1. Limitations

The limitations of the study can be categorized into two main groups: the data collection process and the use of mixed-methods analysis and issues related to data structure and data sharing.

Firstly, the completion of the study required an extended research and analysis process due to the complexity of data collection and the employment of multiple analysis methods. At this point, it is necessary to emphasize that time represents a significant constraint in scientific research. In addition to time limitations, the complex structure of actors and relationships within the social network constituted another major factor necessitating the restriction of the actor sample. In line with the primary aim of the research, the actor sample was thus limited based on the following criteria: (1) being agricultural development cooperatives (ADCs) engaged in food production, (2) operating in agricultural basins with high agricultural production capacity, (3) having procurement guarantee contracts with the İzmir Metropolitan Municipality (IMM), and (4) being agricultural development cooperatives distinguished by their strong local organizational capacities. The limitations related to time constraints and the structure of the social network efforts were overcome by narrowing the scope of the study to the effects of the cooperation model and with cooperatives engaged in guaranteed purchase production contracts through collaborations with the IMM. Based on these criteria, it was identified that the cooperatives selected for the basins were also those recommended for examination by IMM and Cooperative Union (KÖYKOOP) representatives during the interviews. Thus, the final cooperative sample for the study was established.

Secondly, the limitations concerning data structure and data sharing emerged due to the necessity of obtaining the structured dataset required for social network analysis through interviews and with reservations of some actors to express their views on certain issues. During the interviews, questions aimed at determining the economic development levels of the cooperatives, such as annual income, turnover, production, and sales quantities, were left unanswered, as this information was considered commercially sensitive. Consequently, detailed qualitative analyses regarding the cooperatives’ levels of economic development could not be performed. To overcome this limitation, economic development levels were inferred through content analysis based on the assumption that these levels are positively correlated with entrepreneurial characteristics and the prominence of innovative practices within the cooperatives.

Another issue on which the actors were reluctant to express their opinions was the evaluation of the depth of their relationships with public actors. It was identified that this hesitation stemmed from concerns that public administrators might personalize or politicize the situation, potentially leading to administrative or legal sanctions using public authority, thereby negatively impacting the cooperatives. To mitigate this limitation in assessing relationship depth, alternative methods were employed, such as asking the participants to compare relationships by responding to “Which of these two actors do you have a stronger relationship with?” or to rank the actors they have relationships with from the strongest to the weakest.

2.2.2. Original Contributions of the Study

This study provides several original contributions to the field of social network analysis and cooperative network research. Due to the limitations outlined earlier, the sample size in this study was limited to six agricultural development cooperatives out of the 23 that have purchase guarantee agreements with the IMM. While this restricted sample size may initially be perceived as a limitation, it simultaneously represents a critical methodological advantage. Focused sampling enabled the collection of rich, detailed, and high-quality relational data, an in-depth analysis of network structures, actor centrality, and tie structures within the cooperative networks.

Unlike studies based on large-scale networks, where subtle relational patterns and localized network effects often become diluted, this study’s approach provided a fine-grained understanding of micro-level network dynamics within sparse networks. Although the restricted sample limits the generalizability of the findings to broader cooperative networks and diverse geographic or sectoral contexts, the study offers an original contribution to the social network analysis literature by demonstrating how localized relational structures and dense interaction patterns can still be observed within sparse and small-scale networks. Accordingly, the findings should be interpreted within the specific structural and relational context of the selected sample, and future research should aim to validate these results across broader and more heterogeneous network configurations.

Furthermore, the small network size may render key network metrics, such as density and centrality measures, highly sensitive to minor fluctuations. As a result, an actor’s influence may appear overstated or understated in small-scale networks. Nonetheless, an Independent Samples T-Test confirmed that the differences in network centrality between cooperatives located in the KMB and BB were statistically significant.

Overall, the ability to collect highly detailed actor-level data significantly enhanced the study’s capacity to examine relational ties, actor embeddedness, connection patterns, and the overall network structure in depth. These methodological and contextual features distinguish the study from existing large-scale network research and contribute to understanding cooperative network structures under conditions of sparse connectivity and localized collaboration.

3. Results

The entrepreneurial capacities of cooperatives, their innovation processes, and their collaborations with actors at the local, regional, or national level also shape their level of development. One of the key factors determining the effectiveness of collaboration within a cluster or network is the systematic development of technological innovation activities. Therefore, cooperatives with broader networks tend to perform better in innovation processes, thereby achieving a sustainable competitive advantage [39]. Within this context, the thematic content analysis evaluated the development level of cooperatives based on criteria related to innovation and entrepreneurial structure (Table 3). The rationale behind selecting these criteria is as follows: being a pioneer in their respective regions through implemented projects is significant for a cooperative’s institutional culture and development level. Actors seeking to benefit from grants and support provided by regional and national institutions are required to cover a certain portion of the project cost. Therefore, both the project writing and implementation phases necessitate that the applying actor possesses a certain level of development. Sub-criteria considered under innovation include holding patents or registrations, engaging in R&D activities, implementing innovations in production technologies, using renewable energy, adopting innovative marketing strategies, and developing pioneering actions by perceiving changes in the sector. Additionally, factors such as receiving awards, participating in fairs, festivals, and congresses, achieving brand recognition, enhancing institutional reputation, and expanding network relations have been included in the analysis as they contribute to the overall development level of the cooperative.

Table 3.

Evaluation of cooperative development levels based on innovation and entrepreneurial structure criteria.

The cooperatives that reported possessing the criteria listed under the sub-theme are indicated in the interviews column of Table 3. The findings revealed that the development levels of cooperatives and the intensity of innovation practices in their regions vary across the basins. Specifically, cooperatives located in the KMB (actors coded 1, 2, and 3) are more developed than those in the Bakırçay Basin (actors coded 60, 61, and 62).

The development level of cooperatives affects both the number of actors they engage with and the local scale at which these relationships are developed (Table 4).

Table 4.

Spatial and relational patterns of cooperatives based on development level.

The cooperatives that defined relationships with the actors listed in the Actor Receiving the Relationship column of Table 4 are indicated in the Interviews column. The scale of influence of the actors identified by the cooperatives varies between the two basins. It was observed that cooperatives in the BB have more district-scale actor relationships, particularly with private sector entities involved in production processes related to crop patterns. These production relationships are often formed out of necessity due to the ownership of production tools required for specific crop types. In contrast, cooperatives in the KMB not only engage with actors at the district level but also have a strong network of basin-scale relationships. The findings indicate that cooperative-actor interactions are predominantly concentrated at the local level. The reason for the more developed relationships at the district scale is that it represents the primary area of operation for cooperatives, and production relationships are established at this level. Cooperatives that have established relationships with actors at the provincial and national levels were found to have a higher level of development compared to others. This indicates that the level of development influences the spatial scale over which relationships extend and that these cooperatives are also part of more advanced network structures.

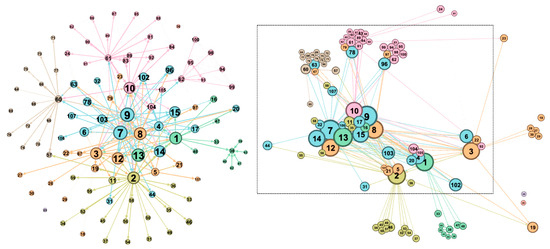

The actor sociomatrix compiled from 15 interviews includes relationship data concerning a total of 107 actors. Network analysis identified 269 ties among these actors. Within the sample, six actor clusters were found to be active (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Actor clusters and network structure in İzmir (color: cluster, line: relationship, circle: actor, circle size: centrality).

Each color in the figure represents a distinct actor cluster and its associated network of relationships. In the schematic representation, larger circles indicate actors with higher centrality values within the network structure. It was observed that each cooperative in the KMB (1, 2, 3) formed its own actor cluster and network of relationships, whereas the cooperatives in the BB (60, 61, 62) are part of the actor cluster centralized around the Cooperative Union (10).

One of the key metrics used in social network analysis is centrality [40]. Centrality refers to the extent to which a node (actor) occupies a central position in the network [41]. The centrality values within the network are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Centrality measures of the actor-network.

Eigenvector centrality indicates the importance of nodes within a network. This metric considers not only the number of ties a node possesses but also the centrality of the nodes to which it is connected [42]. Thus, it plays a crucial role in analyzing the distribution of power within the network. Within this framework, the actors with the highest centrality values are the IMM and the İzmir Provincial Directorate of Agriculture and Forestry. Cooperatives coded 1 and 2, along with IZKA, are second-tier centralized actors at the provincial scale, while the cooperative coded 3 and the Cooperative Union coded 10 are third-tier centralized actors. This pattern suggests that more developed cooperatives establish direct connections with other central actors within the network. Moreover, the findings indicate that the method of relationship formation directly influences eigenvector centrality scores.

Closeness centrality is measured based on the average geodesic distance from a given node to all other nodes in the network. In this context, a node that can reach other nodes through shorter path lengths has higher closeness centrality. This metric yields significant insights in the analysis of social interaction patterns [43]. This measure is essential for assessing how efficiently a node can disseminate information and exert influence throughout the network. In this study, IMM, the Provincial Directorate of Agriculture and Forestry, and the Cooperative Union exhibited the highest closeness centrality values. The findings suggest that these actors are likely to play a more effective role in activities that diffuse rapidly through the network, such as policy implementation and coordination involving cooperatives.

Betweenness centrality quantifies the extent to which a node lies on the shortest paths connecting other nodes. Actors with high betweenness centrality function as brokers, connecting otherwise unlinked parts of the network. It is crucial for identifying actors that serve as brokers, facilitating information flow and structural control across otherwise disconnected parts of the network [44]. In this analysis, IMM, the Cooperative Union, and cooperatives coded 2 and 60 exhibited the highest betweenness centrality values. The inclusion of other actors, identified by cooperatives as having economic ties, through unidirectional links in the analysis and the high volume of such ties has resulted in these cooperatives exhibiting elevated levels of betweenness centrality. Conversely, actors such as the IMM and the Cooperative Union—characterized by mutual ties—emerged as nodes with higher betweenness centrality within the bounded network of interviewed actors. This finding suggests that including reciprocal ties contributes to more consistent and reliable betweenness centrality measurements.

To assess whether the differences in actor centrality between the KMB and BB cooperatives were statistically significant, an Independent Samples T-Test was conducted using eigenvector centrality values as the test variable. Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances indicates that there is a statistically significant difference in variances between the two groups (KMB and BB) with a low p-value (p = 0.008). The results of the t-test indicate that there is a significant difference between the means of eigenvector centrality values for KMB and BB (p = 0.015, at the p < 0.05 significance level). Since there are significant differences in both variance and mean between the two groups, this suggests that eigenvector centrality, which measures the actor-network, differs significantly across these basins.

Overall, the findings indicate that an actor’s orientation toward innovation and entrepreneurship influences its level of organizational development, which in turn affects the structure and extent of its network ties. Accordingly, more developed, such as those coded 1, 2, and 3 in the KMB, exhibit more extensive and advanced network relationships. Their higher development level is also associated with greater centrality within provincial actor-networks. Thus, it can be inferred that the degree of development indirectly influences the centrality structure within the network. The findings also show that cooperatives in the KMB (1, 2, 3) are more entrepreneurial and capable of building their own network relationships, indicating a higher level of development. In contrast, the BB cooperatives (coded 60, 61, 62) are still developing and mainly operate within district-level networks. However, in terms of embedding within province-scale actor-networks, they remain reliant on more central nodes such as the Cooperative Union. The cooperatives’ direct or intermediary ties with the IMM can be linked to their organizational development level and entrepreneurial orientation. Furthermore, the findings highlight that the mode of tie formation within the cooperation model significantly influences how relational networks are structured and how centrality is distributed among actors.

4. Discussion

The content analysis findings reveal that cooperatives coded as 1, 2, and 3 exhibit higher levels of entrepreneurship and innovation compared to others. These results align with prior research identifying entrepreneurship and innovation as fundamental drivers of economic development [39,45,46,47]. The spatial configuration of actor clusters and structurally central nodes (actors) within İzmir province (Figure 3) further provides valuable insights into regional development dynamics as they relate to cooperative advancement. Specifically, centralized local public actors are located in the metropolitan area, while centralized cooperatives (coded 1, 2, 3) are situated in the KMB. The findings regarding centralized actors align with studies that link an actor’s network centrality with its degree—the number of direct ties it maintains [40,41,43,48]. Moreover, they support the view that in small and sparse networks, one or two actors can dominate the network’s structure disproportionately, controlling critical paths between other nodes [41]. In this context, the present study supports previous research indicating that, in sparse networks, a small number of actors (nodes) can control critical paths between other nodes and that some actors bridge structural holes by connecting disconnected parts of the network [41,49]. This dynamic is clearly observed in the findings from the BB case. Structural holes refer to gaps between disconnected groups or individuals within a social network, and actors who bridge these gaps occupy brokerage positions, enabling them to control information flows and access diverse resources. By linking otherwise unconnected parts of the network, brokers gain strategic advantages in terms of innovation, influence, and opportunity creation [49]. In the BB, the Cooperative Union occupies a brokerage position by bridging structural holes between the cluster of local cooperatives and the municipal actor (IMM). The union’s centrality and its role in mediating inter-organizational ties demonstrate how brokerage can emerge from hierarchical membership structures and economic linkages, ultimately influencing both the structural configuration of the network and the developmental trajectories of the cooperatives. These findings suggest that while brokerage roles can facilitate coordination between disconnected groups, they may also introduce asymmetric dependency dynamics, which could adversely impact cooperative development outcomes.

Another important finding concerns the cooperatives that achieved higher centrality within the network. These cooperatives had initiated collaboration with IMM earlier than others, established economic relationships with various public institutions through grants and support programs, and developed innovative projects through these partnerships. This situation supports studies that argue partnerships facilitate inclusion in social networks and that repeated interactions within social networks enhance cooperation [10,20,50].

However, the study also reveals that the same collaboration model did not yield the same outcomes for cooperative development across different basins. In the BB, cooperatives are clustered under the Cooperative Union’s leadership, with the union holding a central brokerage position. The Cooperative Union’s central position within the network can be attributed to hierarchical ties stemming from cooperative membership and its economic linkages with the IMM. This hierarchical structuring fosters a relational dynamic in which cooperative development is mediated through an intermediary actor rather than emerging from direct relational ties. These findings validate the theoretical proposition that the structural configuration of the network (specifically, the presence of brokers bridging structural holes) directly shapes development trajectories. In this context, the study supports the argument that structural holes in the social network, resulting from the lack of connections between two different groups, are bridged by a network broker [51]. In contexts like the BB, reliance on intermediary brokers for establishing inter-organizational ties may limit cooperatives’ autonomy and innovation potential, underlining the critical importance of direct, horizontally structured relational ties in fostering sustainable cooperative growth.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the development levels, institutional dynamics, and local actor relationships of agricultural development cooperatives vary significantly across different basins. Consistent with its research aim, the findings show that both the development levels of actors and the modes of relationship formation within the cooperation model directly influence the actor’s position within the network structure. The results can be synthesized around three key points aligned with the main research questions:

First, cooperative development levels critically affect network relations. As the development level of cooperatives increases, the number and diversity of their relational ties increase, thereby expanding their spatial and operational interaction areas and enhancing opportunities for collaboration.

Second, development levels significantly determine cooperatives’ positions within the social network. More developed cooperatives tend to be more centralized due to a greater number and diversity of relational ties. In addition, innovation and entrepreneurship activities serve as crucial mechanisms through which cooperatives establish ties with other central actors, further reinforcing their network influence.

Third, the cooperation model itself plays a decisive role in shaping both the inter-organizational tie configurations and the positional centrality of actors within the network. The study highlights that the Cooperative Union emerged as a central brokerage node when the IMM engaged with BB cooperatives through this intermediary. This finding indicates that variations in relationship formation within the same cooperation framework can significantly reshape network topology and alter connectivity patterns.

Beyond these general findings, the analysis of the cooperation model based on annual product procurement contracts between IMM and cooperatives offers further insights. This collaboration has enabled producer organizations to integrate into the public food supply chain and provided cooperatives with benefits such as stable income, enhanced credibility, greater visibility, and opportunities to establish new relationships. Leveraging these advantages, cooperatives in the KMB strengthened their innovation and entrepreneurial capacities, emerging as localized hubs with high centrality within the network. However, the same collaboration model did not yield similar outcomes for cooperatives in the BB, instead reinforcing the influence of the Cooperative Union. Despite being administratively considered part of the same province, the two basins exhibit substantial differences in social relations and power dynamics. To further substantiate these observed structural differences, an Independent Samples T-Test was conducted specifically on eigenvector centrality measures. In small-scale networks, fluctuations in key structural metrics such as density and centrality can disproportionately affect the perceived influence and positional advantages of actors. Recognizing this sensitivity, the present study systematically validated the observed differences between the two cooperative networks (KMB and BB) through inferential statistical testing. The statistical confirmation of significant differences in eigenvector centrality strengthens the robustness of the findings by moving beyond descriptive network visualization toward empirical validation. This methodological addition not only enhances the scientific rigor of the analysis but also aligns the study with best practices in empirical social network research, where validating relational patterns statistically is increasingly recognized as essential.

Accordingly, the study’s findings can be consolidated into four major conclusions:

- Cooperatives with higher development focus more on innovation and entrepreneurship-oriented practices. These activities serve as significant indicators for evaluating and understanding the development level of organizations;

- As cooperatives develop, the extent of their relationships expands, and their centrality within the network structure increases. This suggests that enhanced innovation capacity is accompanied by more evolved and robust network relations;

- More developed cooperatives tend to form distinct clusters and emerge as central nodes within the network;

- The collaboration model decisively shapes relationship types and tie structures within the network. There is a clear correlation between the mechanisms of collaboration and network centralization in the network positioning of organizations.

Ultimately, the findings underscore that the structure of collaboration models directly influences network characteristics. Collaborations established through intermediary organizations can create dependencies that may hinder the autonomy and long-term development of cooperatives. Therefore, cooperation models must be designed with sensitivity to local dynamics and the structure of social relationships.

Considering these findings, several policy implications emerge. First, development initiatives aiming to strengthen agricultural cooperatives should prioritize enhancing their innovation and entrepreneurship capacities, as higher development levels are associated with expanded relational networks and stronger centrality within social structures. Targeted interventions—such as innovation support programs, entrepreneurship training, and technical assistance—could foster these capacities. Second, collaboration models should be carefully designed to avoid overreliance on intermediary actors, which can create structural dependencies and limit cooperative autonomy. Instead, policies should promote direct linkages between cooperatives and public institutions to enhance network resilience. Third, regional development strategies must recognize the heterogeneity of local social dynamics, tailoring cooperation models to the specific needs and structures of each locality rather than applying uniform frameworks. Finally, enhancing cooperatives’ visibility and credibility through preferential procurement programs, certification schemes, and public awareness initiatives could further strengthen their roles within local economic networks. By adopting these approaches, policymakers and local stakeholders can more effectively leverage cooperatives as pivotal actors in building inclusive, sustainable, and resilient regional economies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.Y. and T.Ö.E.; methodology, F.Y.; software, F.Y.; formal analysis, F.Y.; data curation, F.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, F.Y.; writing—review and editing, F.Y. and T.Ö.E.; visualization, F.Y.; supervision, T.Ö.E.; project administration, F.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by TÜBİTAK (Türkiye Bilimsel ve Teknolojik Araştırma Kurumu), grant number 117K818.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the procedures approved by the Ethics Committee and approved by the T.C. Gazi University Ethics Committee of the Institute of Science (protocol code E.35942 and 23.02.2021).

Informed Consent Statement

The study is a qualitative research study conducted through semi-structured in-depth interviews. No personal data of the participants was collected, and detailed information regarding the purpose and scope of the study was provided prior to the interviews. Appointments were arranged with participants beforehand, and the in-depth interviews were conducted accordingly. In addition, in studies where official institutions and organizations are considered actors, participants are often reluctant to sign formal consent forms on behalf of the entities they represent. For this reason, before each interview, participants were once again informed about the purpose and methodology of the study, as well as potential risks and benefits. It was emphasized that participation was entirely voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time. Verbal informed consent was obtained and documented in the interview notes.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This article was produced as part of the doctoral dissertation currently being conducted by the corresponding author, Fahriye Yavaşoğlu, supported by the TÜBİTAK project (code: 117K818).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADC | agricultural development cooperative |

| BB | Bakırçay Basin |

| e.g., | exempli gratia |

| IMM | İzmir Metropolitan Municipality |

| ITOM | İl Tarım ve Orman Müdürlüğü |

| IZKA | İzmir Development Agency |

| KMB | Küçük Menderes Basin |

| R&D | research and development |

| KÖYKOOP | S.S. İzmir Tarımsal Kalkınma ve Diğer Tarımsal Amaçlı Kooperatifler Birliği |

| TARİŞ | S.S. Tariş Pamuk ve Yağlı Tohumlar Tarım Satış Kooperatifleri Birliği |

Appendix A

The framework questions in Table A1 were developed to evaluate the changing dimensions of local development within the context of cooperatives, which are considered local economic initiatives.

Table A1.

Semi-structured in-depth interview framework for ADC.

Table A1.

Semi-structured in-depth interview framework for ADC.

| Institutional Structure of the Cooperative | Year of establishmentInfluential actors at the time of establishment Conditions for joining the partnership Activity type and dynamics of service area Number of members Number and type of permanent and seasonal employees and their work areas Key transformation processes since establishment and their reasons |

| R&D Activities | Strategy and innovation (innovations made in the last three years—product, production, service; nature of innovation; the importance of internal resources in innovation processes; sources of innovation—other firms, institutions, customers, etc.; future-oriented programs) Government supports (local/regional/national) R&D projects and expenditures Collaborative research (within and outside the region) Branding |

| Actor Relationships | Types of relationships among cooperatives (production technology, institutional structure, innovative and entrepreneurial partnerships, etc.) and interaction hierarchies Types of relationships between cooperatives and local/central government units (economic, technical, and social support structures; inclusion in network relationships; capacity to create participatory decision-making mechanisms) Relationships between cooperatives and other local/regional/national economic actors (production, R&D projects, market and marketing relations) |

| Development Trend | Increase in number of members Increase in production Increase in turnover Increase in collaborations with other actors Growth in movable and immovable assets Production growth forecast for the next three years |

The framework questions in Table A2 were designed to test the reliability of the information received from the cooperatives and to enable a cross-evaluation by other local actors regarding local development, the agricultural sector, cooperative activities, and production organization.

Table A2.

Semi-structured in-depth interview framework for formal government structures and chambers.

Table A2.

Semi-structured in-depth interview framework for formal government structures and chambers.

| Institutional Structure of the Local Actor | Year of establishment Name of specialized units for the sector Total number of employees (engineers, technicians, administrative staff) Core services provided for the sector Main markets Percentage of sales (local/national) Import and export activities R&D supports Services received from the sector |

| Local and Regional Economic Factors | Current structure of the agricultural sector Growth potential Value added Income levels |

| Human Capital and Cooperative Development | Regional and sectoral education services Regional capabilities |

| Governance and Participation | Regulatory impact on agricultural production and rural development Support mechanisms for agricultural development Planning regulations |

| Infrastructure, Rural Environment, and Planning | Infrastructure for agricultural production and marketing Transportation infrastructure and accessibility Infrastructure for production and information and communication technologies |

| Grants and Supports Provided to Agricultural Development Cooperatives | Types and scope of supports applied by cooperatives Budgets of approved projects Implementation and progress status of the projects |

References

- DPT. Dokuzuncu Kalkınma Planı 2007–2013: Bölgesel Gelişme Özel İhtisas Komisyonu Raporu; DPT: Ankara, Türkiye, 2008; pp. 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Geray, C. Kooperatifçilik; Nika Yayınevi: Ankara, Türkiye, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Guadaño, J.; Lopez-Millan, M.; Sarria-Pedroza, J. Cooperative entrepreneurship model for sustainable development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas, W.P.; Pedroso, B.; Vargas, L.M.; Picinin, C.T.; Freitas Júnior, M.A.D. Cooperative organization and its characteristics in economic and social development (1995 to 2020). Sustainability 2022, 14, 8470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchetti, S.; Tortia, E. The internal and external governance of cooperatives: The effective membership and consistency of value. In Euricse Working Paper; University of Bologna: Bologna, Italia, 2012; No. 62/13. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley, T.J. Moving beyond Dyadic Ties: A network theory of stakeholder influences. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 887–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, E. Innovation networks for social impact: An empirical study on multi-actor collaboration in projects for smart cities. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavaşoğlu, F.; Özelçi Eceral, T. Aktör ağ ilişkileri bağlamında sosyal sermaye, yerel kooperatifler, bölgesel kalkınma: İzmir, Ödemiş Bademli Kooperatifi. Bölgesel Kalkınma Derg. 2023, 1, 374–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saz-Gil, I.; Bretos, I.; Díaz-Foncea, M. Cooperatives and social capital: A narrative literature review and directions for future research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, R.; Prokop, D. Network structure and regional innovation: A study of university–industry ties. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 931–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Li, C.; Liu, L.; Li, T. Opinion polarization over signed social networks with quasi-structural balance. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2022, 9, 3447–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Li, T. Reaching opinion consensus on leader-follower signed social networks with communication delays. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2023; ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Brass, D.J.; Galaskiewicz, J.; Greve, H.R.; Tsai, W. Taking stock of networks and organizations: A multilevel perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 795817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisneros-Velarde, P.; Bullo, F. A network formation game for the emergence of hierarchies. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Xi, Y. Exploring dynamic multi-level linkages in ınter-organizational networks. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2006, 23, 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, P.S.; van de Ven, A.H. Developmental processes of cooperative interorganizational relationships. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1994, 19, 90–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okem, A.E.; Lawrence, R. Exploring the opportunities and challenges of network formation for cooperatives in South Africa. KCA J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 5, 16–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.T.; Teng, G.F. Formation and computation of relationship in complex social networks. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 427, 2687–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.J.; Lin, Y.H. The effect of network relationship on the performance of SMEs. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1780–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyytinen, K. Multi-actor collaboration for the development of service innovations. Eur. Rev. Serv. Econ. Manag. 2016, 2016, 143–174. [Google Scholar]

- Huremovic, K. Rent Seeking and Power Hierarchies: A Noncooperative Model of Network Formation with Antagonistic Links. Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei Working Papers 2014, Paper 908. Available online: https://services.bepress.com/feem/paper908/ (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Beer, A.; Haughton, G.; Maude, A. International comparisons of local and regional economic development. In Developing Locally; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2003; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Abbey, P.; Tomlinson, P.R.; Branston, J.R. Perceptions of governance and social capital in Ghana’s cocoa ındustry. J. Rural. Stud. 2016, 44, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi. 743 sayılı Zirai Kredi Kooperatifleri Kanunu; Resmi Gazete: Ankara, Türkiye, 1929; No. 1208. Available online: https://www5.tbmm.gov.tr/tutanaklar/KANUNLAR_KARARLAR/kanuntbmmc007/kanuntbmmc007/kanuntbmmc00701470.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi. 2834 Sayılı Tarım Satış Kooperatifleri ve Birlikleri Hakkında Kanun; Resmi Gazete: Ankara, Türkiye, 1935; No. 3146. Available online: https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/arsiv/3146.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi. Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Anayasası; Resmi Gazete: Ankara, Türkiye, 1961; No. 10859. Available online: https://www.tbmm.gov.tr/files/anayasa/docs/1961/1961-ilkhali/1961-ilkhali.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi. 1163 sayılı Kooperatifler Kanunu; Resmi Gazete: Ankara, Türkiye, 1969; No. 13159. Available online: https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/mevzuat?MevzuatNo=1163&MevzuatTur=1&MevzuatTertip=5 (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Şenses, F. Neoliberal Küreselleşme ve Kalkınma; İletişim Yayınları: Ankara, Türkiye, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi. 6360 sayılı On Üç İlde Büyükşehir Belediyesi ve Yirmi Altı İlçe Kurulması ile Bazı Kanun ve Kanun Hükmünde Kararnamelerde Değişiklik Yapılmasına Dair Kanun; Resmi Gazete: Ankara, Türkiye, 2012; No. 28489. Available online: https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2012/12/20121206-1.htm (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Tekeli, İ. İzmir İli/Kenti İçin Bir Tarımsal Gelişme ve Yerleşme Stratejisi; Akdeniz Akademisi: İzmir, Türkiye, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tek, M.; Çelebi, H.İ. Büyükşehir belediye yönetimleri için yerel kalkınma modeli: Kooperatifler. In Kırsal Kalkınma ve Kooperatfiçilik; Mengi, A., İşçioğlu, D., Eds.; Ankara Üniversitesi Basımevi: Ankara, Türkiye, 2019; pp. 645–668. [Google Scholar]

- İzmir Kalkınma Ajansı. İzmir Kooperatif Analizi; İzmir Kalkınma Ajansı: İzmir, Türkiye, 2022; Available online: https://izka.org.tr/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/KOOPERATIF-ANALIZI.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- İzmir Kalkınma Ajansı. 2014–2023 İzmir Bölge Planı; İzmir Kalkınma Ajansı: İzmir, Türkiye, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- İzmir Tarım ve Orman İl Mudurluğu. III. Tarım Şurası Hazırlık Raporu; İzmir Tarım ve Orman İl Mudurluğu: İzmir, Türkiye, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- İzmir Tarım ve Orman İl Mudurlüğü. Kuçuk Menderes Havzası Ana Raporu; İzmir Tarım ve Orman İl Mudurluğu: İzmir, Türkiye, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Aşçı, T. Büyükşehir ile Tarım Kooperatifleri Arasında Büyük Sözleşme: Başkan Soyer’den 338 Milyonluk Ürün Alım Sözü. Ege Postası, 27 Ocak 2021. Available online: https://www.egepostasi.com/haber/Buyuksehir-ile-tarim-kooperafleri-arasinda-buyuk-sozlesme-Baskan-Soyerdem-338-milyonluk-urun-alim-sozu/253919 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Yavaşoğlu, F. Sosyal Ağ Kuramı Çerçevesinde Mekan, Yerel İş Birliği ve Kooperatifçilik: İzmir Örneği. Ph.D. Thesis, Gazi University, Ankara, Türkiye, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hanneman, R.A. Computer-Assisted Theory Building: Modeling Dynamic Social Systems; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Fakhrutdinova, E.; Mokichev, S.; Kolesnikova, J. The influence of cooperative connections on innovation activities of enterprises. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 27, 212–215. [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Mehra, A.; Brass, D.J.; Labianca, G. Network analysis in the social sciences. New Ser. 2009, 323, 892–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, S.; Faust, K. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bonacich, P. Factoring and weighting approaches to status scores and clique identification. J. Math. Sociol. 1972, 2, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.C. Centrality in social networks: Conceptual clarification. Soc. Netw. 1978, 1, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.C. A set of measures of centrality based on betweenness. Sociometry 1977, 40, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.J.; Audretsch, D.B. Entrepreneurship, innovation and technological change. Found. Trends® Entrep. 2005, 1, 149–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Theory Of Economic Development; Harvard Economic Studies: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Sciascia, S.; De Vita, R. The Development Of Entrepreneurship Research; Universita Carlo Cattaneo: Castellanza, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Uzzi, B. Social structure and competition in interfirm networks: The paradox of embeddedness. Adm. Sci. Q. 1997, 42, 35–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Dall’Asta, L.; Marsili, M.; Pin, P. Collaboration in social networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 4395–4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. Structural holes and good ideas. Am. J. Sociol. 2004, 110, 349–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).