Towards Inclusive Waste Management in Marginalized Urban Areas: An Expert-Guided Framework and Its Pilot in Reșița, Romania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Expert Consultation and Data Collection

2.2. Qualitative Analysis and Framework Synthesis

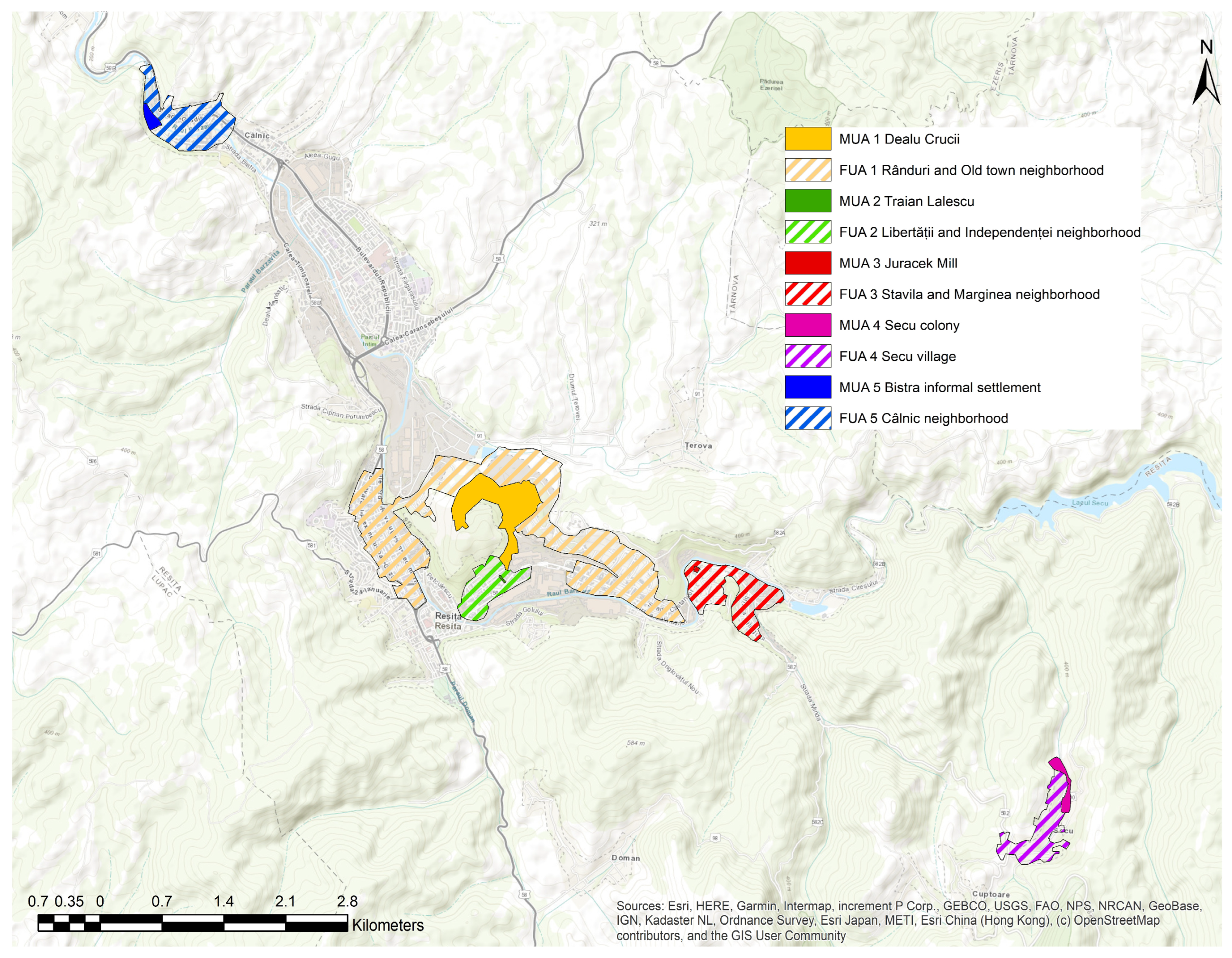

2.3. Selection of the Pilot Community, Reșița’s Marginalized Urban Areas

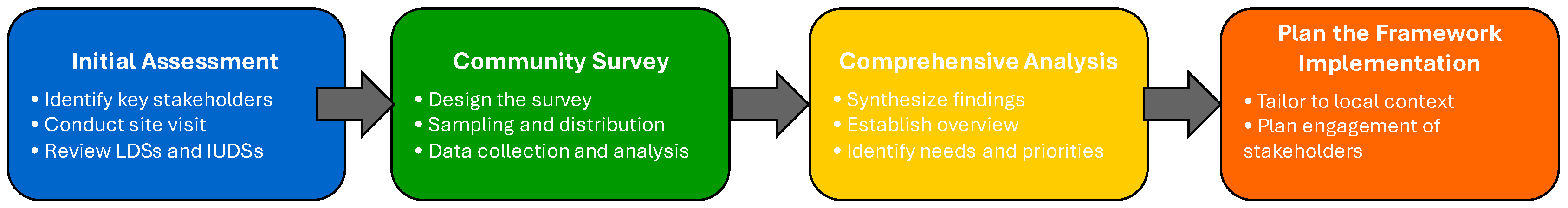

2.4. Framework Deployment Plan

2.5. Community Survey Design and Administration

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Challenges in Waste Management for Marginalized Urban Areas (Expert Perspectives)

3.2. Potential Strategies for Mitigating the Challenges (Expert Proposed Solutions)

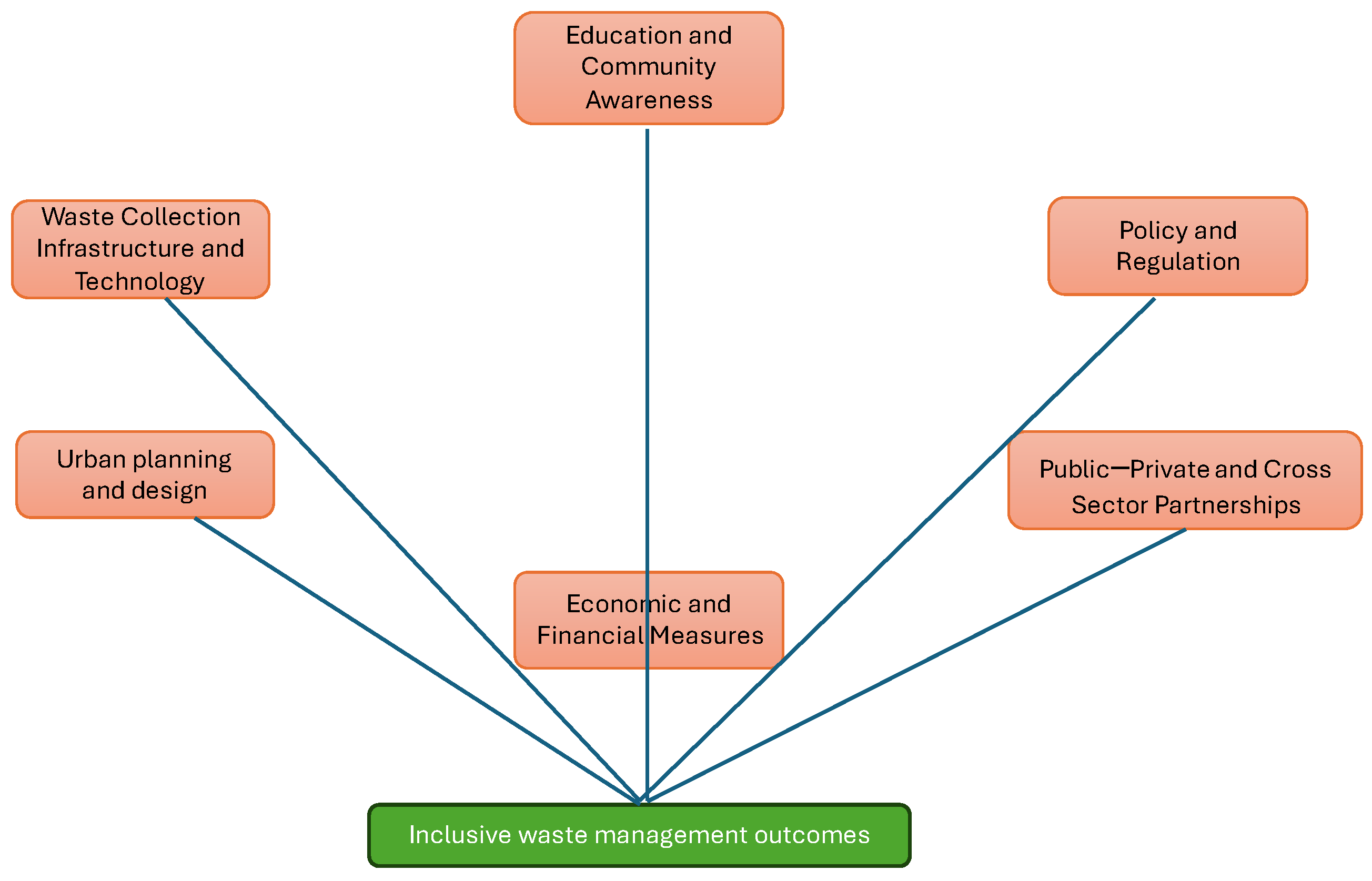

3.3. Development of the Integrated Waste Management Framework

3.4. Case Study in Reșița’s MUAs

3.4.1. Overview of Reșița’s Marginalized Areas

3.4.2. Initial Site Observations

3.4.3. Stakeholder Mapping

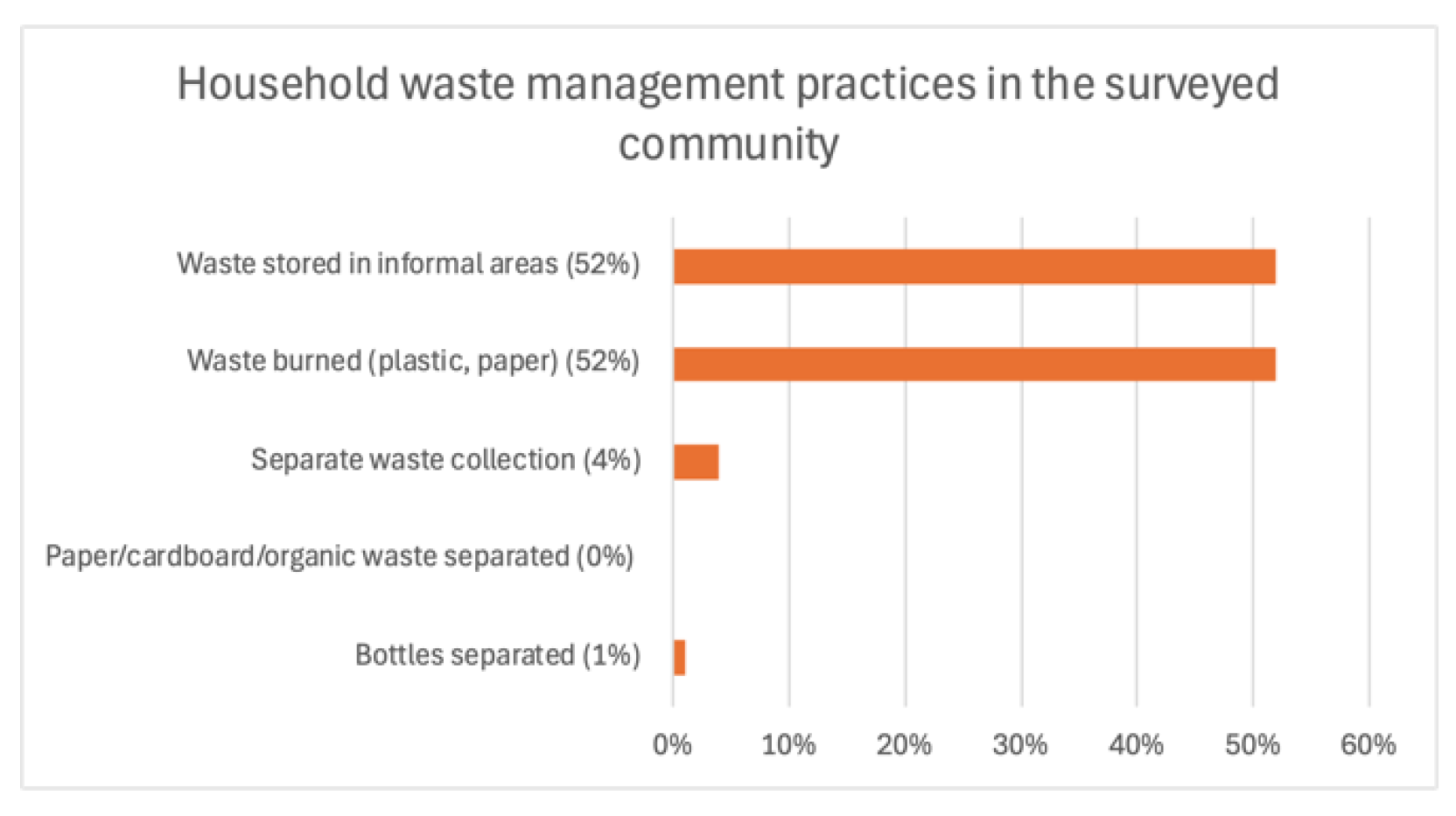

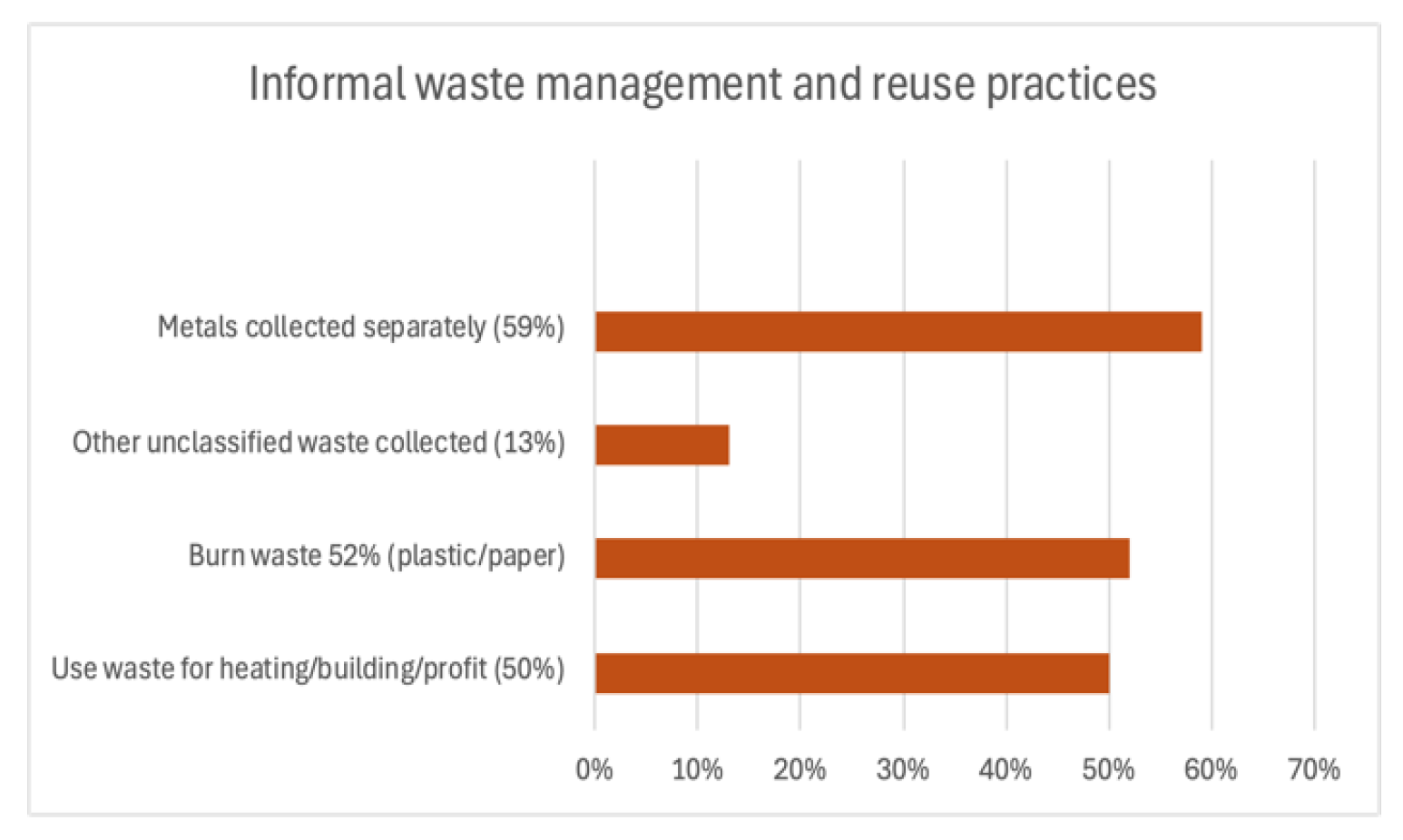

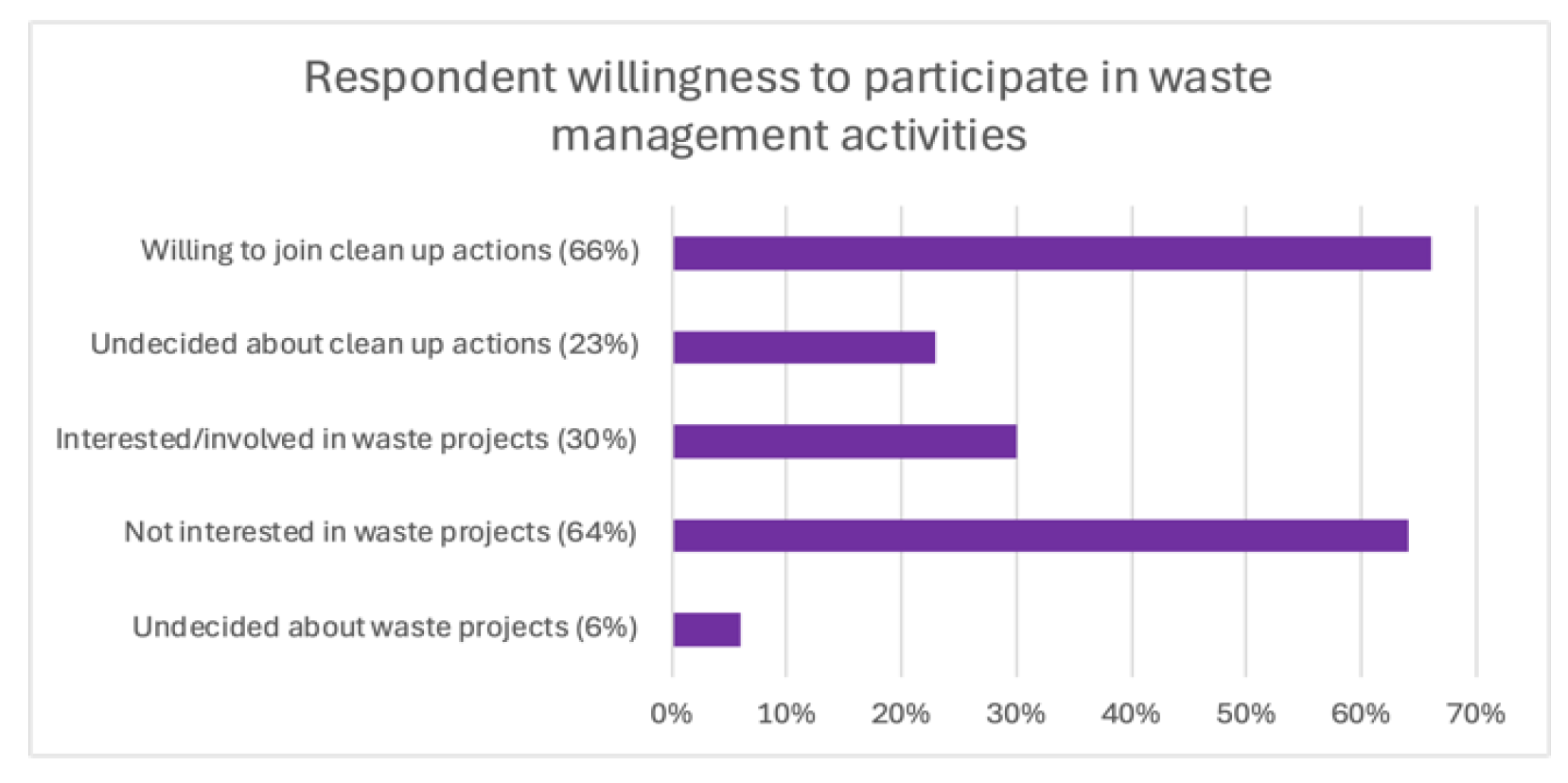

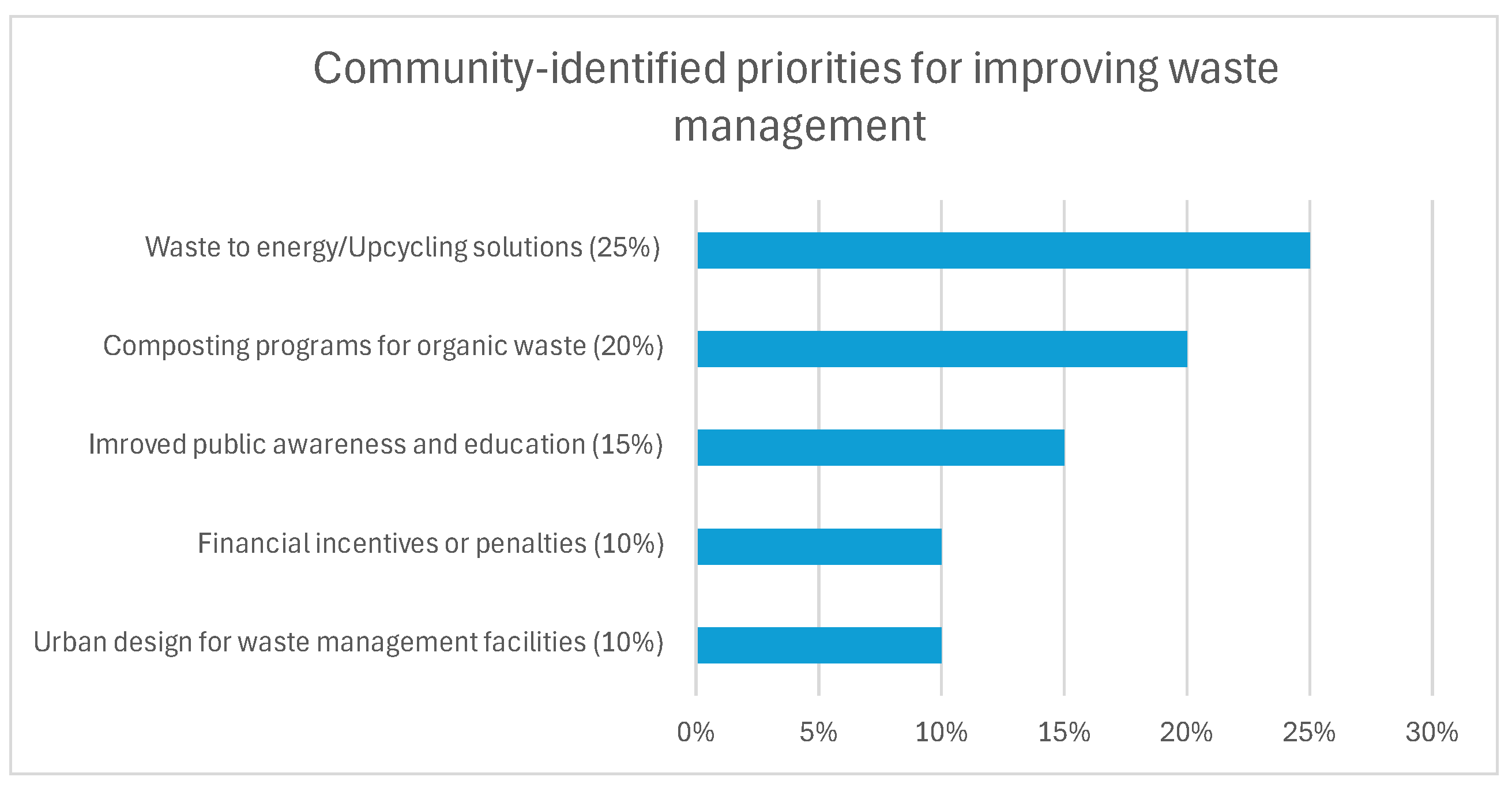

3.4.4. Analysis of Survey Responses in Reșița

3.5. Framework Deployment Matrix

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilson, D.C.; Velis, C.; Cheeseman, C. Role of informal sector recycling in waste management in developing countries. Habitat Int. 2006, 30, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2018. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/2018-revision-of-world-urbanization-prospects.html (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Kaza, S.; Yao, L.C.; Bhada-Tata, P.; Van Woerden, F. What a Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050. Urban Development. World Bank. 2018. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/d3f9d45e-115f-559b-b14f-28552410e90a (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Giusti, L. A review of waste management practices and their impact on human health. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 2227–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P.A., Pirani, S.L., Connors, C., Péan, S., Berger, N., Caud, Y., Chen, L., Goldfarb, M.I., Gomis, M., et al., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lissah, S.Y.; Ayanore, M.A.; Krugu, J.K.; Aberese-Ako, M.; Ruiter, R.A.C. Managing urban solid waste in Ghana: Perspectives and experiences of municipal waste company managers and supervisors in an urban municipality. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omang, D.I.K.; John, G.E.; Inah, S.A.; Bisong, J.O. Public health implication of solid waste generated by households in Bekwarra Local Government area. Afr. Health Sci. 2021, 21, 1467–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.K.; Das, B.; Bhardwaj, P.K.; Tampha, S.; Singh, H.K.; Chanu, L.D.; Sharma, N.; Devi, S.I. Socio-economic sustainability with circular economy—An alternative approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 166630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaman, F.; Iacoboaea, C.; Aldea, M.; Luca, O.; Stănescu, A.A.; Boteanu, C.M. Energy Transition in Marginalized Urban Areas: The Case of Romania. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlamentul României. Legea nr.350/2001 a Amenajării Teritoriului și Urbanismului, Modificată Prin Legea nr.151/2019; Parlamentul României: Bucureşti: Bucureşti, Romania, 2019.

- Ghid de Intervenție Urbanistică Participativă în Așezările Informale din România, Asociația Make Better 2023. Available online: https://locuireinformala.ro/resurse/ (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Guvernul României. Ordonanța de Urgență nr. 183/2022 Privind Stabilirea Unor Măsuri Pentru Finanțarea Unor Proiecte de Regenerare Urbană; Guvernul României: Bucureşti, Romania, 2022.

- Raport Privind Așezările Informale din România, 2022 Ministerul Dezvoltării, Lucrărilor Publice și Administrației. Available online: https://www.mdlpa.ro/pages/habitat (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Pires, A.; Graça, M.; Ni-Bin, C. Solid waste management in European countries: A review of systems analysis techniques. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 1033–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, S.M. Waste pickers and cities. Environ. Urban. 2016, 28, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrescu-Mag, R.M.; Petrescu, D.C.; Oroian, I.G.; Safirescu, O.C.; Bican-Brișan, N. Environmental Equity through Negotiation: A Case Study on Urban Landfills and the Roma Community. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunajeva, J.; Kostka, J. Racialized politics of garbage: Waste management in urban Roma settlements in Eastern Europe. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2021, 45, 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincze, E. Landfill: Space of Advanced and Racialized Urban Marginality in Today’s Romania. SPAREX Working Paper. 2012. Available online: http://sparex-ro.eu/wp-content/uploads/landfill-Clujadvanced-marginality2012.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Iacoboaea, C.; Luca, O.; Șercăianu, M.; Aldea, M.; Păunescu, M.; Popescu, A.L. Towards Sustainable Modes for Remote Monitoring in Waste Management: A Study of Marginalized Urban Areas in Romania. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F. Strategies to perform a mixed methods study. Eur. J. Educ. Stud. 2018, 5, 137–151. [Google Scholar]

- Akbarpour, N.; Salehi-Amiri, A.; Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M.; Oliva, D. An innovative waste management system in a smart city under stochastic optimization using vehicle routing problem. Soft Comput. 2021, 25, 6707–6727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, X.; Bloemhof, J.M.; Ramos, T.R.P.; Barbosa-Povoa, A.P.; Wong, C.Y.; van der Vorst, J.G. Research challenges in municipal solid waste logistics management. Waste Manag. 2016, 48, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, M.; Talib, M.A.; Feroz, S.; Nasir, Q.; Abdalla, H.; Mahfood, B. Artificial intelligence applications in solid waste management: A systematic research review. Waste Manag. 2020, 109, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, A.T.; Varbanov, P.S.; Nižetić, S.; Sirohi, R.; Pandey, A.; Luque, R.; Ng, K.H.; Pham, V.V. Perspective review on Municipal Solid Waste-to-energy route: Characteristics, management strategy, and role in circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 359, 131897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, S.J.; Lewlyn, L.R.R. Behavioral aspects of solid waste management: A systematic review. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2020, 70, 1268–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concari, A.l.; Gerjo, K.; Martens, P. A systematic literature review of concepts and factors related to pro-environmental consumer behaviour in relation to waste management through an interdisciplinary approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsini, F.; Gusmerotti, N.M.; Testa, F.; Iraldo, F. Exploring waste prevention behaviour through empirical research. Waste Manag. 2018, 79, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agamuthu, P.; Hansen, J.A. Universities in capacity building in sustainable development: Focus on solid waste management and technology. Waste Manag. Res. 2007, 25, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.; Scott, S.; Geddes, A. Snowball sampling. In SAGE Research Methods Foundations; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2019; 13p. [Google Scholar]

- Sutrop, M.; Lõuk, K. Informed consent and ethical research. In Handbook of Research Ethics and Scientific Integrity; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 213–232. [Google Scholar]

- Shoozan, A.; Maslawati, M. Application of interview protocol refinement framework in systematically developing and refining a semi-structured interview protocol. In Proceedings of the 5th Annual Conference on Education and Social Sciences (ACcESS 2023), Mataram, Indonesia, 2–3 November 2023; SHS Web of Conferences: Les Ulis Cedex A, France, 2024; Volume 182, p. 04006. [Google Scholar]

- Swinkels, R.; Stanculescu, M.; Anton, S.; Koo, B.; Man, T.; Moldovan, C. Atlasul Zonelor Urbane Marginalizate din Romania; Banca Mondială: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Strategia de Dezvoltare Locală a Grupului de Acțiune Local Reșița. 2023. Available online: https://galresita.ro/strategia-de-dezvoltare-locala/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Grupul de Acțiune Local Reșița. Available online: https://galresita.ro/despre-noi/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Luca, O.; Gaman, F.; Răuță, E. Towards a national harmonized framework for urban plans and strategies in Romania. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, A.K.L. Structured questionnaires. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Manohar, N.; MacMillan, F.; Steiner, G.Z.; Arora, A. Recruitment of research participants. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 71–98. [Google Scholar]

- Rochel, J. Ethics in the GDPR: A blueprint for applied legal theory. Int. Data Priv. Law 2021, 11, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-Fernández, L.; Escobar-Farfán, M. Zero-Waste Management and Sustainable Consumption: A Comprehensive Bibliometric Mapping Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.T.; Nguyen, N.; Phung, P.; Yến-Khanh, N. Residents’ waste management practices in a developing country: A social practice theory analysis. Environ. Chall. 2023, 13, 100770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogiannidis, S.; Kontsas, S.; Syndoukas, D.; Chatzitheodoridis, F. Integrative mechanisms towards zero emissions regional planning: An enabler of regional development $ da case study of Europe. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2024, 14, 450–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, P. Solid waste management-sustainability towards a better future, role of CSR–a review. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 15, 762–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, S.; Islam, S.; Jahan, F.; Khatun, F. Awareness and practice on household solid waste management among the community people. Open J. Nurs. 2021, 11, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotosusilo, A.; Utari, D.; Negoro, H.A.; Firdaus, A.; Velentina, R.A. Community empowerment of waste management in the urban environment: More attention on waste issues through formal and informal educations. Glob. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2022, 8, 209–224. [Google Scholar]

- Sekito, T.; Prayogo, T.; Dote, Y.; Yoshitake, T.; Bagus, I. Influence of a community-based waste management system on people’s behavior and waste reduction. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 72, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filčák, R.; Stager, T. Ghettos in Slovakia. Confronting Roma social and enviromental exclusion. Anal. Krit. 2014, 36, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, F.C.; Gündoğdu, S.; Markley, L.A.; Olivelli, A.; Khan, F.R.; Gwinnett, C.; Gutberlet, J.; Reyna-Bensusan, N.; Llanquileo-Melgarejo, P.; Meidiana, C.; et al. Plastic pollution, waste management issues, and circular economy opportunities in rural communities. Sustainability 2021, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, A.U.; Lehmann, S. Urban growth and waste management optimization towards ‘zero waste city’. City Cult. Soc. 2011, 2, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simatele, D.M.; Dlamini, S.; Kubanza, N.S. From informality to formality: Perspectives on the challenges of integrating solid waste management into the urban development and planning policy in Johannesburg, South Africa. Habitat Int. 2017, 63, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Klundert, A.; Anschütz, J. Integrated Sustainable Waste Management: The Concept—Tools for Decision-makers. In Experiences from the Urban Waste Expertise Programme (1995-2001); WASTE: Gouda, The Netherlands, 2001; 46p. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.primariaresita.ro/portal/cs/resita/portal.nsf/AllByUNID/programe-si-strategii-000043b6?OpenDocument (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Guvernul României. Ordonanța de Urgență nr. 92/2021 Privind Regimul Deșeurilor; Guvernul României: Bucureşti, Romania, 2021.

- Konecčnyý, O. The Leader Approach Across the European Union: One Method of Rural Development, Many Forms of Implementation. Eur. Countrys. 2019, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayilara, M.S.; Olanrewaju, O.S.; Babalola, O.O.; Odeyemi, O. Waste management through composting: Challenges and potentials. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.I.; Khurram, S. Food waste recycling for compost production and its economic and environmental assessment as circular economy indicators of solid waste management. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 317, 128467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Sharma, A.; Bhardwaj, L.; Gupta, P.; Sharma, A.; Bhardwaj, L. Solid Waste Management (SWM) and Its Effect on Environment & Human Health. Preprints 2023, 2023090384. [Google Scholar]

- Vinti, G.; Bauza, V.; Clasen, T.; Medlicott, K.; Tudor, T.; Zurbrügg, C.; Vaccari, M. Municipal Solid Waste Management and Adverse Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Profile | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental scientists and engineers | 8 | 22% |

| Sanitation operators | 7 | 19% |

| Urban planners and architects | 6 | 16% |

| Waste management practitioners and consultants | 9 | 24% |

| Public policy makers and authorities’ representatives | 4 | 11% |

| Academics and researchers | 3 | 8% |

| Factors | Questions |

|---|---|

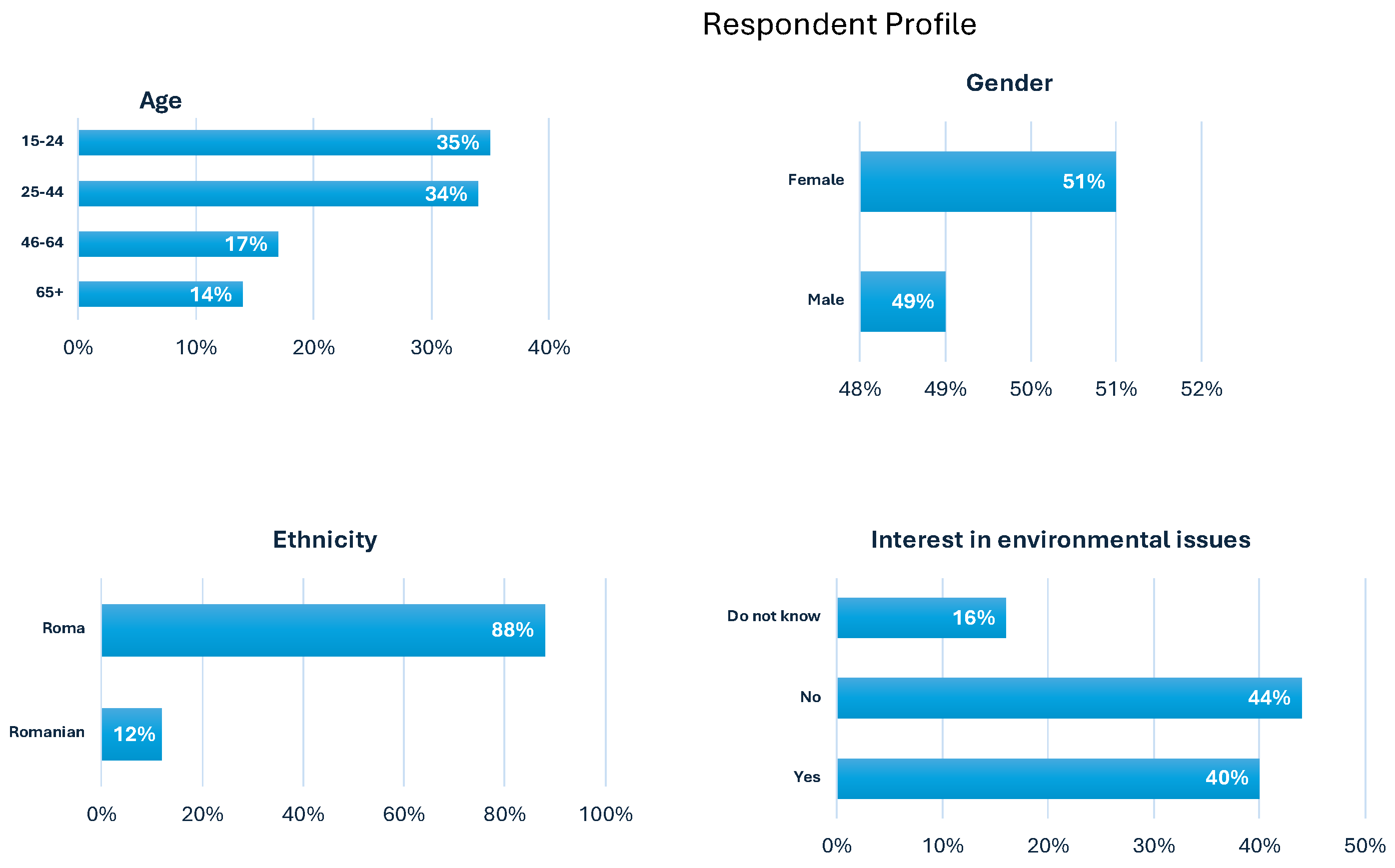

| Socio-demographics | We asked respondents about their age, gender, ethnicity, and housing status (owner, tenant, or informal occupant) to contextualize the data and check representation across community sub-groups. |

| Current waste practices | Questions in this section inquired how households typically dispose of their waste (e.g., use municipal collection, dump it in an open area, burn it, etc.), whether they separate any materials for recycling or reuse, and if they engage in informal waste-related activities (like collecting scrap metal or using waste as fuel). We included specific yes/no and multiple-choice questions, such as “Do you burn household waste (plastic, paper, etc.)?” and “Where do you mostly put your garbage?” |

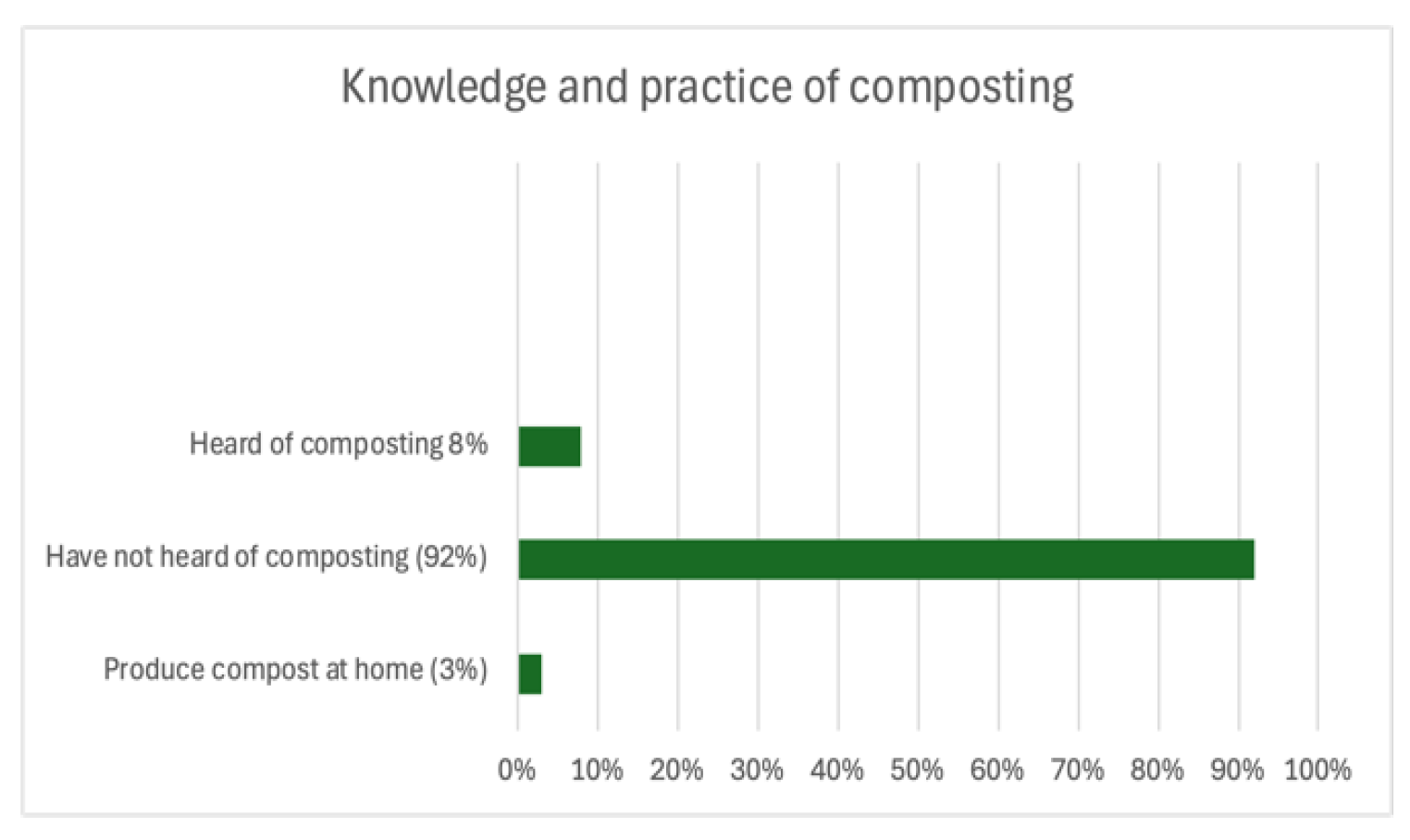

| Knowledge and awareness | To assess residents’ familiarity with waste management concepts, we asked whether they had heard of terms like composting, recycling, or seen any local campaigns about waste. One question was, “Have you heard of composting as a way to manage organic waste? If yes, do you practice it?” to estimate both awareness and adoption. |

| Attitudes and willingness | We presented scenarios to measure willingness to participate in improvement efforts. For instance, “Would you be willing to join community clean-up actions in your area?” (Yes/No/Maybe), and “How interested are you in attending workshops on waste reduction and recycling?” We also asked about willingness to separate waste if provided with the necessary resources, and preferences for incentives (e.g., lower fees) to encourage participation. |

| Perceived priorities and issues | An open-ended question and a checklist were used to learn what residents see as the biggest waste problem in their area (options included infrequent collection, insufficient bins, illegal dumping, health problems, etc.) and what improvements they most want to see (e.g., “more frequent trash pickup”, “free dumpsters provided”, “stricter enforcement against littering”, etc.). |

| Engagement with authorities | We asked if residents were aware of any ongoing initiatives by the city or NGOs to improve cleanliness and if they had ever reported a waste issue or contacted authorities about it. |

| Challenge Area | Summary of Experts’ Insights |

|---|---|

| Behavior and environment | Experts emphasized that the absence of regular waste collection and clean public spaces negatively influences resident behavior and community morale. As one expert noted, “visible cleanliness can reinforce positive behaviors and community pride”. This insight aligns with the existing literature demonstrating the correlation between environmental cues and pro-environmental behavior [39,40]. |

| Illegal dumping | Illegal dumping was unanimously identified as a major concern, particularly in areas with absent or irregular waste collection. Experts described how open dumping contributes to soil and water pollution and attracts vermin. These concerns corroborate the findings of [41], which identify service deficits as predictors of illicit disposal practices. |

| Budgetary constraints and technical gaps | Several experts highlighted that financial limitations and insufficient technical capacity hinder municipalities from extending formal services to marginalized zones. An expert observed, “Even when funds exist, there may be insufficient know-how to design inclusive systems”. These insights are echoed in equity-focused urban planning research [42]. |

| Social responsibility and health | A recurring theme was the societal obligation to protect environmental health. Experts advocated for shared responsibility and educational outreach to support behavioral change, consistent with the findings in [43]. |

| Community education and awareness of WM practices | Low levels of environmental awareness were identified as a core barrier. Experts emphasized the role of informal educators (e.g., teachers, community health workers) in increasing waste literacy. This view is supported by empirical studies on localized educational strategies [44,45,46]. |

| Social stigmatization and exclusion | Experts underscored that unmanaged waste exacerbates social stigma and perpetuates exclusion. One planner described this as “garbage becoming part of the identity imposed on these communities”. Such dynamics are explored in depth by the authors of [47]. |

| Poverty and specific local challenges | Economic difficulties and insecure tenure were described as key obstacles to accessing waste services. Informal recycling was noted as both a survival strategy and a gap in policy integration. These observations mirror findings in sustainability studies focused on rural and under-resourced settings [48]. |

| Waste as a resource in the circular economy | Experts linked improved waste practices to reductions in methane emissions and enhanced material recovery, particularly in underserved areas. These views reflect circular economy strategies with climate mitigation co-benefits [48]. |

| WM and urban planning | Urban planners stressed the necessity of embedding waste infrastructure from the outset in spatial design. Retrofitting was described as cost-inefficient and often exclusionary. This is consistent with urban planning research advocating for holistic, design-integrated waste systems [49,50]. |

| Needs | Findings |

|---|---|

| Related to the provisions of the current legal framework |

|

| In the field of housing sanitation |

|

| Regarding sanitation of the areas adjacent to the municipality |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Phase | Focus Area | Timeline | Lead Actors | Objective |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Stakeholder Mobilization and Framework Adaptation | Months 1–2 | Municipal authorities, NGOs, LAGs, CBOs | Establish governance structure; localize framework through consultations and capacity-building. |

| 2 | Education and Community Engagement | Months 2–6 | NGOs, CBOs, schools, municipality | Raise awareness of segregation, recycling, and health through tailored campaigns and events. |

| 3 | Infrastructure Development | Months 3–10 | Municipal departments, private contractors | Install inclusive infrastructure; optimize logistics using GIS, particularly in irregular or high-density urban layouts; support decentralization. |

| 4 | Policy and Regulatory Implementation | Months 6–12 | Local government, legal advisors | Enact enabling policies, incentivize compliance, and control illegal dumping. |

| 5 | Urban Integration and Sustainable Planning | Months 6–18 | Urban planning departments, local authorities | Embed waste goals into city planning; enable access and sustainable neighborhood design. This includes allocating space for waste facilities, ensuring truck access, and applying sustainable neighborhood design principles. |

| 6 | Economic and Institutional Sustainability | Months 8–20 | Economic departments, private sector, NGOs | Develop circular economy models (resource recovery and circular economy opportunities, focusing on compost production, plastic recycling, and upcycled materials); support social enterprises; leverage public–private synergy. Micro-grants or social enterprise models can be used to support local initiatives (e.g., waste pickers’ cooperatives). |

| 7 | Additional Contextual Measures | Ongoing from Month 6 | NGOs, CBOs, municipality | Adjust operations to local needs (e.g., clean-up events, flexible pickups, feedback loops). These interventions should remain flexible and locally tailored. |

| 8 | Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning | Months 6–24+ | Municipality, academic partners, CBOs | Establish indicators and feedback systems to track results, refine, and scale interventions. Regular feedback loops with community members should be maintained to refine and adapt implementation strategies. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iacoboaea, C.; Damian, A.; Nenciu, I.; Aldea, M.; Luca, O.; Șercăianu, M.; Neagu, A.; Răuță, E. Towards Inclusive Waste Management in Marginalized Urban Areas: An Expert-Guided Framework and Its Pilot in Reșița, Romania. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5070. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115070

Iacoboaea C, Damian A, Nenciu I, Aldea M, Luca O, Șercăianu M, Neagu A, Răuță E. Towards Inclusive Waste Management in Marginalized Urban Areas: An Expert-Guided Framework and Its Pilot in Reșița, Romania. Sustainability. 2025; 17(11):5070. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115070

Chicago/Turabian StyleIacoboaea, Cristina, Andrei Damian, Ioana Nenciu, Mihaela Aldea, Oana Luca, Mihai Șercăianu, Ancuța Neagu, and Emanuel Răuță. 2025. "Towards Inclusive Waste Management in Marginalized Urban Areas: An Expert-Guided Framework and Its Pilot in Reșița, Romania" Sustainability 17, no. 11: 5070. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115070

APA StyleIacoboaea, C., Damian, A., Nenciu, I., Aldea, M., Luca, O., Șercăianu, M., Neagu, A., & Răuță, E. (2025). Towards Inclusive Waste Management in Marginalized Urban Areas: An Expert-Guided Framework and Its Pilot in Reșița, Romania. Sustainability, 17(11), 5070. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115070