Social Factors and Policies Promoting Good Health and Well-Being as a Sustainable Development Goal: Current Achievements and Future Pathways

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Role of Socioeconomic Factors in Public Health and Connection with SDG 3

3. Current Achievements in Promoting SDG 3

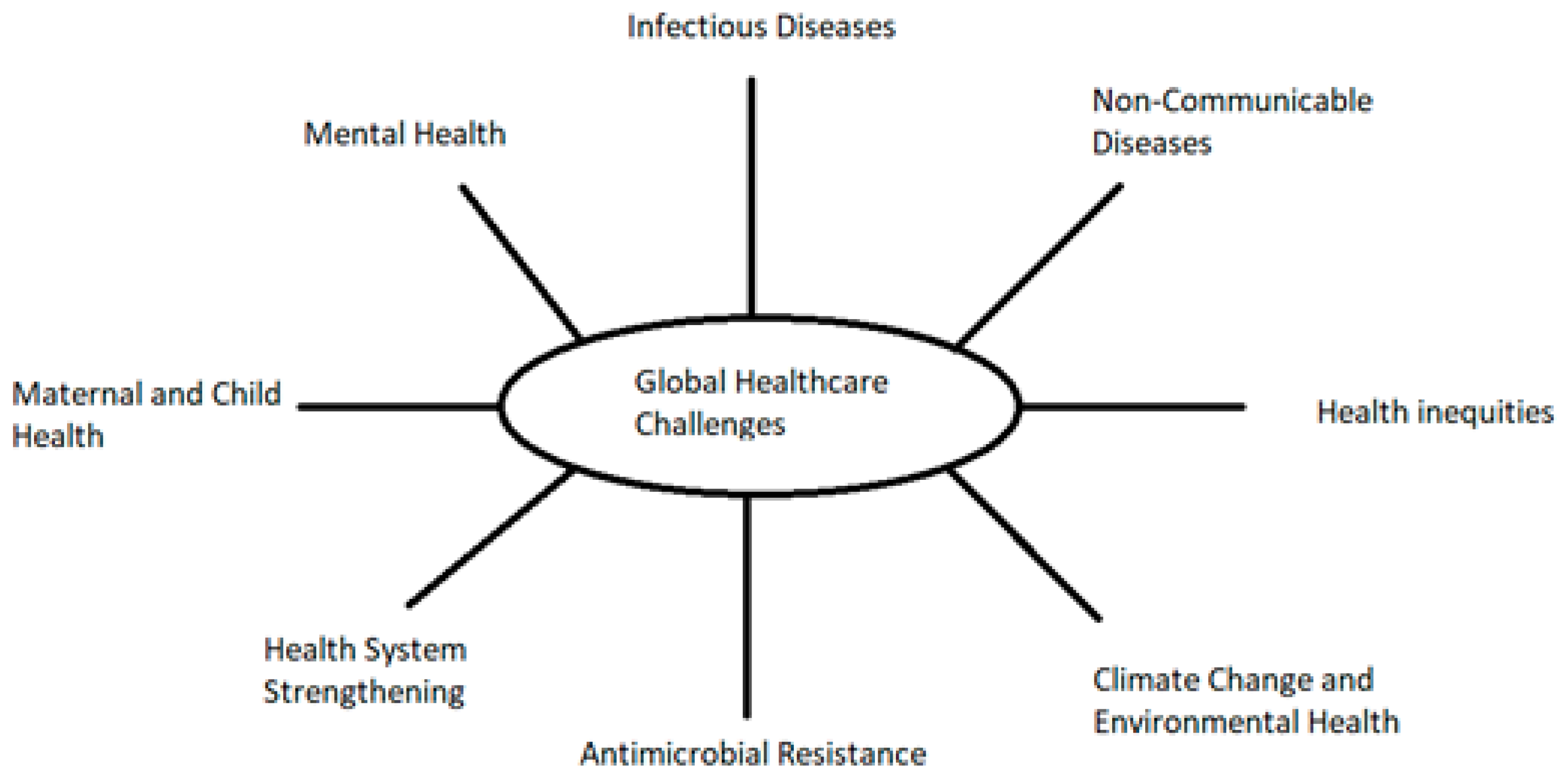

4. Challenges and Gaps in Achieving SDG 3

5. Future Pathways and Social Policy Recommendations

5.1. Strategies for Strengthening Social Policies in Health

5.2. Role of Technology and Innovation

5.3. Collaboration Between Sectors for Sustainable Health Improvements

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| NCDs | Non-Communicable Diseases |

| CVDs | Cardiovascular Diseases |

| AMI | Any Mental Illness |

| SMI | Serious Mental Illness |

| LMICs | Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| GHGs | Greenhouse Gases |

References

- Byskov, J.; Maluka, S. A Systems perspective on the importance of global health strategy developments for accomplishing today’s Sustainable Development Goals. Health Policy Plan. 2019, 34, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.J.; Farber, M.K.; Taha, B.W. Epidemiology, trends, and disparities in maternal mortality: A framework for obstetric anesthesiologists. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2024, 38, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhutta, Z.A.; Das, J.K.; Bahl, R.; Lawn, J.E.; Salam, R.A.; Paul, V.K.; Sankar, M.J.; Blencowe, H.; Rizvi, A.; Chou, V.B.; et al. Newborn Interventions Review Group; Lancet Every Newborn Study Group. Can available interventions end preventable deaths in mothers, newborn babies, and stillbirths, and at what cost? Lancet 2014, 384, 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raina, N.; Khanna, R.; Gupta, S. Progress in achieving SDG targets for mortality reduction among mothers, newborns, and children in the WHO South-East Asia Region. Lancet Reg. Health Southeast Asia 2023, 18, 100307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Kim, R.; Subramanian, S.V. Economic-related inequalities in child health interventions: An analysis of 65 low- and middle-income countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 277, 113816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath, S.; Khedr, A. Pandemics throughout the history. Cureus 2021, 13, 18136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljeldah, M. Antimicrobial resistance and its spread is a global threat. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, A.; Al-Amin, Y. Antimicrobial resistance: A growing serious threat for global public health. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toner, E.; Adalja, A. Antimicrobial resistance is a global health emergency. Heal Secur. 2015, 13, 153–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Oxford. Antibiotic Resistance. Available online: https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2024-09-17-antibiotic-resistance-has-claimed-least-one-million-lives-each-year-1990 (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Berche, P. The Spanish Flu. Presse Med. 2022, 51, 104127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, D.; Cadarette, D. Infectious disease threats in the twenty first century: Strengthening the Global response. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/deaths (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Islam, S.; Purnat, T. Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in developing countries: A symposium report. Glob. Health 2014, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panamerican Health Organization (PAHO). Noncommunicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/topics/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Vaduganathan, M.; Mensah, G. The global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk: A compass for future health. JACC 2022, 80, 2361–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Noncommunicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- National Institute Mental Health (NIMH), USA, Mental Health Information, Statistics, Mental Illness. Available online: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Compton, M.T.; Shim, R.S. The Social Determinants of Mental Health. Focus 2015, 13, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC (European Commission). Public Health, Mental Health, EU Comprehensive Approach to Mental Health. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/non-communicable-diseases/mental-health_en (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Vigo, D.V.; Patel, V.; Becker, A.; Bloom, D.; Yip, W.; Raviola, G.; Saxena, S.; Kleinman, A. A partnership for transforming mental health globally. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.; Andersen, J. Outdoor air pollution and cancer: An overview of the current evidence and public health recommendations. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 10, 3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, V.; Feng, Y. Air pollution, greenhouse gases and climate change: Global and regional perspectives. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoro, K.; Daramola, M. Chapter 1—CO2 emission sources, greenhouse gases, and the global warming effect. Adv. Carbon Capture 2020, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeder, D. Chapter 9: Fossil fuels and climate change. In Fracking and the Environment; Springer: Rapid City, SD, USA, 2021; pp. 155–185. [Google Scholar]

- Manisalidis, I.; Stavropoulou, E. Environmental and Health Impacts of air pollution: A review. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 505570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drakaki, E.; Dessinioti, C.; Antoniou, C.V. Air pollution and the skin. Front. Environ. Sci. 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaezi, A.; Shahbazi, R.; Sheikh, M.; Lak, R.; Ahmadi, N.; Kaskaoutis, D.G.; Behrooz, R.D.; Sotiropoulou, R.-E.P.; Tagaris, E. Environmental pollution and human health risks associated with atmospheric dust in Zabol City, Iran. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2024, 17, 2491–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzavella, F.; Vgenopoulou, I.; Fradelos, E.C. Climate change as a social determinant of the quality of public health. Arch. Hell. Med. 2021, 38, 401–409. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (World Health Organisation). Everybody business: Strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO’s framework for action, 2007. In WHO Library Cataloguing-In-Publication Data; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; ISBN 978 92 4 159607 7. [Google Scholar]

- Mosnaim, G.; Carrasquel, M. Social Determinants of Health and COVID-19. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2023, 11, 3347–3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unicef, Strengthening Health Systems. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/health/strengthening-health-systems (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Kruk, M.E.; Gage, A.D.; Arsenault, C.; Jordan, K.; Leslie, H.H.; DeWan, S.R.; Adeyi, O.; Barker, P.; Daelmans, B.; Doubova, S.V.; et al. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: Time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health 2018, 6, e1196–e1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Health Inequities and Their Causes. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/facts-in-pictures/detail/health-inequities-and-their-causes (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Bailey, Z.; Krieger, N. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet 2017, 389, 1453–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, S.; Taaffe, J. The Sustainable Development Goals and the Global Health Security Agenda: Exploring synergies for a sustainable and resilient world. J. Public Health Policy 2017, 38, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowou, R.K.; Amu, H.; Saah, F.I. Increased investment in Universal Health Coverage in Sub-Saharan Africa is crucial to attain the Sustainable Development Goal 3 targets on maternal and child health. Arch. Public Health 2023, 81, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G. The SDGs and the UN Summit of the Future. In Sustainable Development Report 2024; Dublin University Press: Dublin, Ireland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Odoch, W.D.; Senkubuge, F.; Hongoro, C. How has sustainable development goals declaration influenced health financing reforms for universal health coverage at the country level? A scoping review of literature. J. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangcharoensathien, V.; Mills, A.; Palu, T. Accelerating health equity: The key role of universal health coverage in the Sustainable Development Goals. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou, C.; Kaitelidou, D.; Karanikolos, M.; Maresso, A. Greece: Health System Review. Health Syst. Transit. 2017, 19, 1–166. [Google Scholar]

- Emmanouilidou, M. The 2017 Primary Health Care (PHC) reform in Greece: Improving access despite economic and professional constraints? Health Policy 2021, 125, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greer, S.; Jarman, H. What is EU Public Health and why? Explaining the Scope and Organization of Public Health in the European Union. J. Health Politics Policy Law 2021, 46, 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenk, J.; Moon, S. Governance challenges in global health. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN (United Nations) II. Sounding the Alarm: SDG Progress at the Midpoint. 2023. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/progress-midpoint/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Boulos, D.; Hassan, A. Using the Health Belief Model to assess COVID-19 perceptions and behaviours among a group of Egyptian adults: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pub. Health 2023, 23, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanberry, L.R.; Thomson, M.C.; James, W. Prioritizing the Needs of Children in a changing climate. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, M.S.D.; Medeiros, K.S.D.; Seixas, C.T.; Nobre, T.T.X. Evaluation instruments for public health policies for elderly care: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e091477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, K.; Thierry, A.D.; Taylor, H.O. Institutional, neighborhood, and life stressors on loneliness among older adults. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picchio, M.; Ubaldi, M. Unemployment and health: A meta-analysis. J. Econ. Surv. 2024, 38, 1437–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sage, D. Do Active Labour Market Policies Promote the Well-Being, Health and Social Capital of the Unemployed? Evidence from the UK. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 124, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, C.P.; Parr, H. Climate change and rural mental health: A social geographic perspective. Rural. Remote Health 2020, 20, 6337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenharo, M. How to recover when a climate disaster destroys your city. Nature 2024, 634, 1032–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apap, J.; Harju, S.J. The Concept of ‘Climate Refugee’ Towards a Possible Definition; PE 698.753; European Parliamentary Research Service: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Berchin, I.I.; Valduga, I.B.; Garcia, J.; Guerra, J.B.S.O.d.A. Climate change and forced migrations: An effort towards recognizing climate refugees. Geoforum 2017, 84, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diem, G.; Brownson, R.C.; Grabauskas, V.; Shatchkute, A.; Stachenko, S. Prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases through evidence-based public health: Implementing the NCD 2020 action plan. Glob. Health Promot. 2015, 23, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.J.; Ahn, M. Boomers’ intention to choose healthy housing materials: An application of the Health Belief Model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamer, A.S. Behavior Change Theories and Models Within Health Belief Model Research: A Five-Decade Holistic Bibliometric Analysis. Cureus 2024, 16, e63143. [Google Scholar]

- Iluno, A.C.; Oshiname, F.O.; Adekunle, A.O.; Dansou, J. Cervical cancer screening adoption behaviors among Nigerian women in academics: Using a health belief model. BMC Women’s Health 2024, 24, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes-Lara, C.; Zeler, I.; Moreno, Á.; De Troya-Martín, M. Sun behavior: Exploring the health belief model on skin cancer prevention in Spain. J. Public Health 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.C. Foundations of health promotion and the socio-ecological model. In Health Promotion Moving Forward: A Population Health Approach; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Caperon, L.; Saville, F. Developing a socio-ecological model for community engagement in a health programme in an uderserved urban area. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275092. [Google Scholar]

- Manyani, A.; Biggs, R.; Hill, L.; Preiser, R. The evolution of social-ecological systems (SES) research: A co-authorship and co-citation network analysis. Ecol. Soc. 2024, 29, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, A.I.; Peters, R.M.H.; De Sabbata, K.; Mengistu, B.S.; Agusni, R.I.; Alinda, M.D.; Darlong, J.; Listiawan, M.Y.; Prakoeswa, C.R.S.; Walker, S.L.; et al. A socio-ecological model of the management of leprosy reactions in Indonesia and India using the experiences of affected individuals, family members and healthcare providers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zou, Y.; Zhao, L.; Chen, Y.; Qiu, Y. Facilitators and barriers in managing older chronic heart failure patients in community health care centers: A qualitative study of medical personnel’s perspectives using the socio-ecological model. Front. Health Serv. 2025, 5, 1483758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarkang, E.E.; Amu, H. Application of the socio-ecological model in the efforts to end COVID-19 in Sub-Saharan Africa: The challenges and success stories. Malawi Med. J. 2023, 35, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slivsek, G.; Vitale, K.; Loncarek, K. How Do Changes in the Family Structure and Dynamics Reflect on Health: The Socio-Ecological Model of Health in the Family. Med. Flum. 2024, 60, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hasdell, P.; Gao, C.; Pan, Y.; Wang, B.; Jian, I.Y. Connection, deviation, patterns, and trends: Visualizing the interplay of sustainability science and social–ecological system research. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 504, 145431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordova-Pozo, K.L. Digitalization in Healthcare and Health Data Reporting: Opportunities to Reduce Error and Inequality of Healthcare Delivery. Int. J. Community Based Nurs. Midwifery 2025, 13, 161–163. [Google Scholar]

- Strange, M.; Zdravkovic, S.; Gustafsson, H.; Mangrio, E. Everyday Digitalization of Health Care: The Experiences of Dental Healthcare Workers in a Diverse Swedish Region. Int. J. Health Wellness Soc. 2025, 15, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafferty, K.A. The Digitalization of Customer Contact in Healthcare Management for Professionals; Part F79; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankar, N.J.; Khatib, K.N.; Bandre, G.R.; Kale, S.G. Use of Robotics in Healthcare Digitalization. AIP Conf. Proc. 2024, 3188, 100020. [Google Scholar]

- Pisarra, M.; Marsilio, M. Digitalization and SDGs accounting: Evidence from the public healthcare sector. Public Money Manag. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, L.C.; Lin, Y.; Pang, G.; Sanderson, J.; Duan, K. Digitalization to achieve greener healthcare supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 463, 142802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Hernández, E.J. Challenges of health and well-being in the world according to SDG indicators. Cienc. E Saude Coletiva 2024, 29, e15782022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodali, P. Achieving Universal Health Coverage in Low- and Middle- Income Countries: Challenges for Policy Post-Pandemic and Beyond. Risk Man. Health Policy 2023, 16, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shattock, A.J.; Johnson, H.C.; Sim, S.Y.; Carter, A.; Lambach, P.; Hutubessy, R.C.W.; Thompson, K.M.; Badizadegan, K.; Lambert, B.; Ferrari, M.J.; et al. Contribution of vaccination to improved survival and health: Modelling 50 years of the Expanded Programme on Immunization. Lancet 2024, 403, 2307–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boakye-Agyemang, C. Healthy Life Expectancy in Africa Has Risen by Almost Ten Years. 2022. WHO Regional Office for Africa. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/news/healthy-life-expectancy-africa-rises-almost-ten-years (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Singh Thakur, J.; Nangia, R.; Singh, S. Progress and challenges in achieving noncommunicable diseases targets for the sustainable development goals. FASEB Bioadv. 2021, 3, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN DESA. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2024—June 2024; UN DESA: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2024/ (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Selvaraj, A.K.; Naveen Akash, P.; Venkata Swamy, B. Understanding the Aftermath of COVID-19: A Data-Driven Exploration of Health Effects. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Data Communication Technologies and Internet of Things, IDCIoT 2025, Bengaluru, India, 5–7 February 2025; pp. 172–177. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, G.; Rodriguez, R.; Padin, C. A Lesson for Sustainable Health Policy from the Past with Implications for the Future. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

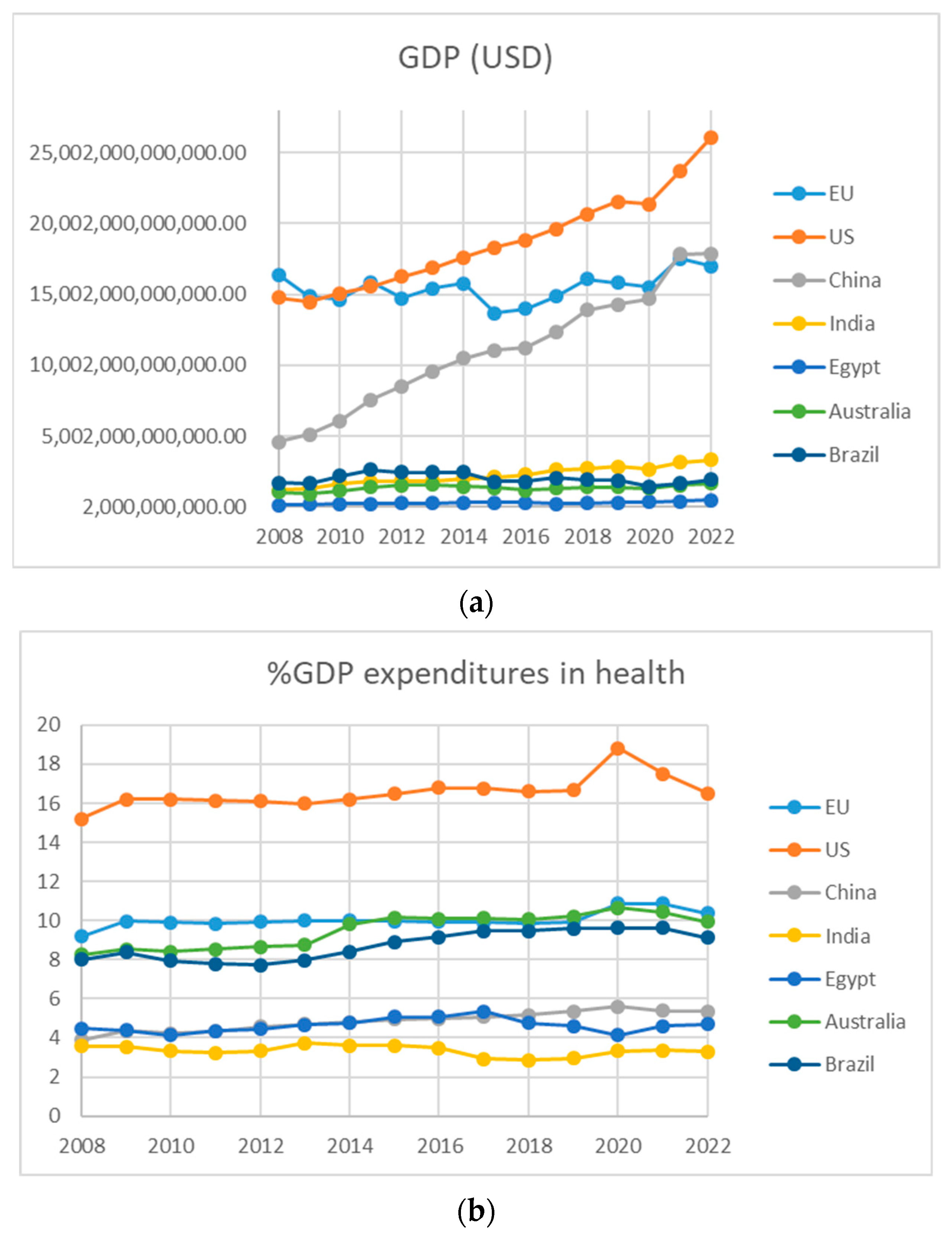

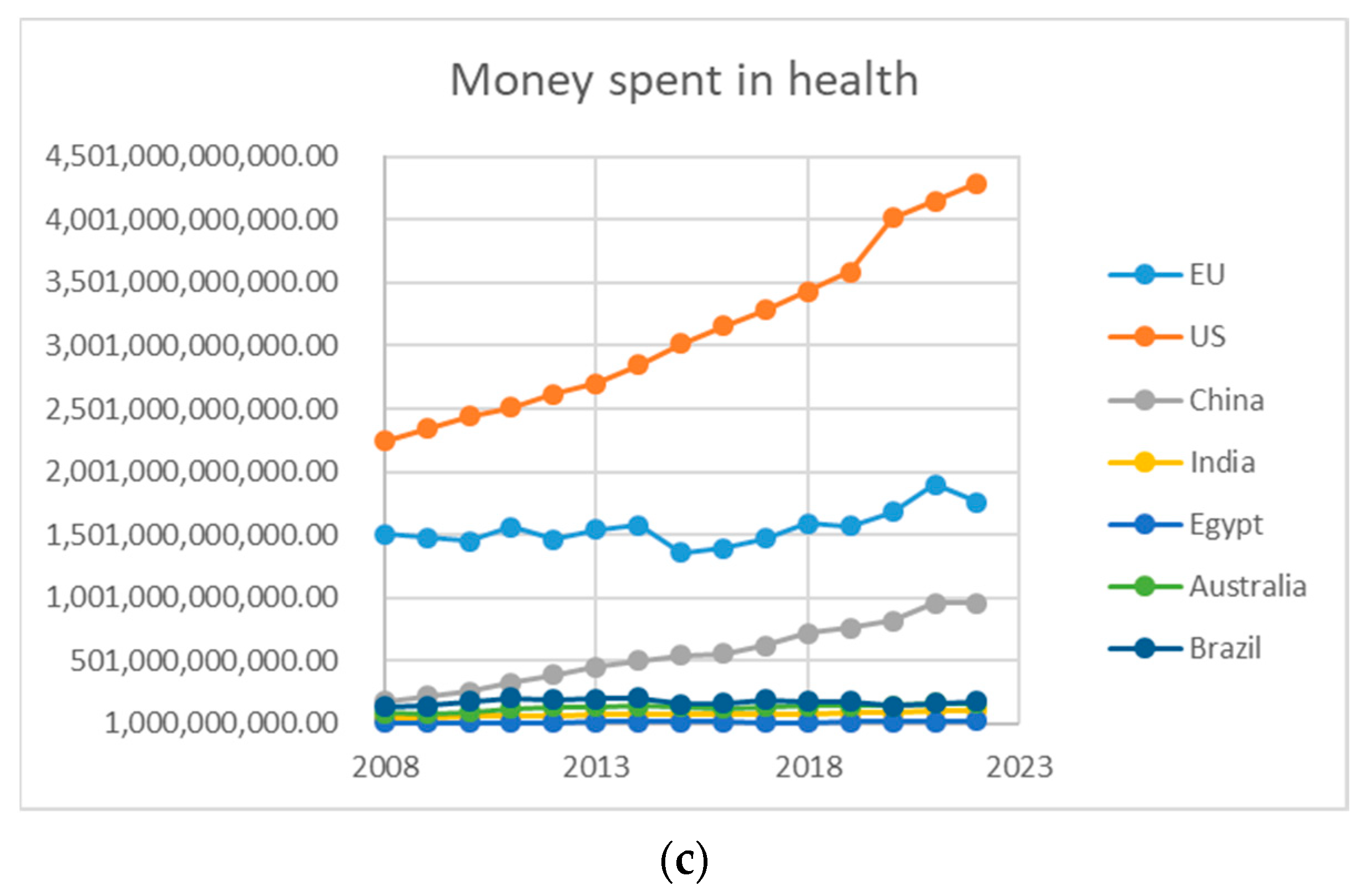

- Onofrei, M.; Vatamanu, A.-F.; Vintilă, G.; Cigu, E. Government Health Expenditure and Public Health Outcomes: A Comparative Study among EU Developing Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banik, B.; Roy, C.K.; Hossain, R. Healthcare Expenditure, Good Governance and Human Development. Economia 2022, 24, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/Health---world-and-EU-health-exp-to-GDP/id/1f6f751e (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- WHO (World Health Organization). Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978 92 4 151113 1. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/250368/9789241511131-eng.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), University of Washington. Available online: https://www.healthdata.org/news-events/newsroom/news-releases/lancet-more-39-million-deaths-antibiotic-resistant-infections (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Alderwick, H.; Briggs, A. The impacts of collaboration between local health care and non-health care organizations and factors shaping how they work: A systematic review of reviews. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penchansky, R.D.B.A.; Thomas, J.W. The Concept of Access: Definition and Relationship to Consumer Satisfaction. Med. Care 1981, 19, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.J.; Vonneilich, N.; Lüdecke, D.; von dem Knesebeck, O. Income, Financial Barriers to Health Care and Public Health Expenditure: A Multilevel Analysis of 28 Countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 176, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.V.; Petruzzi, L.; Jones, C.; Cubbin, C. An Intersectional Approach to Understanding Barriers to Healthcare for Women. J. Community Health 2023, 48, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, S. How Social Policies Can Improve Financial Accessibility of Healthcare: A Multi-Level Analysis of Unmet Medical Need in European Countries. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, M.; D’Agostino, D.; Gregory, P. Addressing Rural Health Challenges Head On. Mo. Med. 2017, 114, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Isaacs, B. Save Rural Health Care: Time for a Significant Paradigm Shift. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2019, 119, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, O.K.; Higashi, R.T.; Makam, A.N.; Mijares, J.C.; Lee, S.C. The Influence of Financial Strain on Health Decision-Making. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2018, 33, 406–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO (World Health Organization). Gender and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/gender#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Roberts, T.K.; Fantz, C.R. Barriers to Quality Health Care for the Transgender Population. Clin. Biochem. 2014, 47, 983–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persaud, A.; Bhugra, D.; Valsraj, K.; Bhavsar, V. Understanding Geopolitical Determinants of Health. Bull. World Health Organ. 2021, 99, 166–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gostin, L.O.; Friedman, E.A. The Sustainable Development Goals: One Health in the World’s Development Agenda. JAMA 2015, 314, 2621–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Kamradt-Scott, A. The Multiple Meanings of Global Health Governance: A Call for Conceptual Clarity. Glob. Health 2014, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persaud, A.; Bhat, P.S.; Ventriglio, A.; Bhugra, D. Geopolitical Determinants of Health. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2018, 27, 308–310. [Google Scholar]

- Huijts, T.; McNamara, C.L. Trade Agreements, Public Policy and Social Inequalities in Health. Glob. Soc. Policy 2017, 18, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamadi, E.; Kraemer, A.; Majdzadeh, R.; Mohamadzade, M.; Mohammadshahi, M.; Kiani, M.M.; Ebrahimi, F.; Mostafavi, H.; Olyaeemanesh, A.; Takian, A. Impacts of Economic Sanctions on Population Health and Health System: A Study at National and Sub-National Levels from 2000 to 2020 in Iran. Glob. Health 2024, 20, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebano, A.; Hamed, S.; Bradby, H.; Gil-Salmerón, A.; Durá-Ferrandis, E.; Garcés-Ferrer, J.; Azzedine, F.; Riza, E.; Karnaki, P.; Zota, D.; et al. Migrants’ and Refugees’ Health Status and Healthcare in Europe: A Scoping Literature Review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariadi, S.; Saud, M.; Ashfaq, A. Exploring the Role of NGOs’ Health Programs in Promoting Sustainable Development in Pakistan. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium of Public Health (ISOPH 2017)—Achieving SDGs in South East Asia: Challenging and Tackling of Tropical Health Problems, Surabaya, Indonesia, 11–12 November 2017; pp. 430–435, ISBN 978-989-758-338-4. [Google Scholar]

- Doshmangir, L.; Sanadghol, A.; Kakemam, E.; Majdzadeh, R. The Involvement of Non-Governmental Organisations in Achieving Health System Goals Based on the WHO Six Building Blocks: A Scoping Review on Global Evidence. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0315592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.S.; Blanchard, A.Κ.; Blencowe, H.; Koon, A.D.; Boerma, T.; Sharma, S.; Campbell, O.M.R. Zooming in and out: A holistic framework for research on maternal, late foetal and newborn survival and health. Health Policy Plan. 2022, 37, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasin, N.; Amnuaylojaroen, T.; Saokaew, S. Prenatal PM2.5 Exposure and Its Association with Low Birth Weight: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Toxics 2024, 12, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinia, S.S.; Yang, K.-H.; Lee, E.J.; Lim, M.-N.; Kim, J.; Kim, W.J. Effects of heavy metal exposure during pregnancy on birth outcomes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrigan, P.J.; Fuller, R.; Acosta, N.J.R.; Adeyi, O.; Arnold, R.; Basu, N.; Baldé, A.B.; Bertollini, R.; Bose-O’Reilly, S.; Boufford, J.I.; et al. The Lancet Commission on pollution and health. Lancet 2018, 391, 462–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawn, J.E.; Blencowe, H.; Waiswa, P.; Amouzou, A.; Mathers, C.; Hogan, D.; Flenady, V.; Frøen, J.F.; Qureshi, Z.U.; Calderwood, C. Stillbirths: Rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. Lancet 2016, 387, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, O.M.; Graham, W. J Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: Getting on with what works. Lancet 2006, 368, 1284–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerber, K.J.; de Graft-Johnson, J.E.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Okong, P.; Starrs, A.; Lawn, J.E. Continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health: From slogan to service delivery. Lancet 2007, 370, 1358–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou, C. Chapter 14 Learning from the economic and the pandemic crisis. Health system resilience in Greece: From Skylla to Charibdis. In Handbook of Health System Resilience; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S. Public Health System and Socio-Economic Development Coupling Based on ST. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souliotis, K.; Papadonikolaki, J. Resilient health reforms in times of permacrisis: The Greek citizens’ perspective. Front. Political Sci. 2024, 6, 1470412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, D. Sociology of Exclusion in the Era of Globalization; Motivo Publishing: Athens, Greece, 2012. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, M.; Jessani, N.; Bennett, S. Identifying health policy and systems research priorities for the sustainable development goals: Social protection for health. Int. J. Equity Health 2018, 17, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakioti, E.; Angelopoulos, N.; Tomaras, V. Attitudes and perceptions of staff and resident-patients in residential units in Thessaly. Psychiatriki 2014, 25, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tzavella, F. Society and Health in the 21st Century; Sideris Publishing: Athens, Greece, 2018; (In Greek). ISBN 9789600807998. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, S.; Jessani, N.; Glandon, D.; Qiu, M.; Scott, K.; Meghani, A.; El-Jardali, F.; Maceira, D.; Javadi, D.; Ghaffar, A. Understanding the implications of the Sustainable Development Goals for health policy and systems research. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Umair, M.; Khan, S.; Alonazi, W.B.; Almutairi, S.S.; Malik, A. Exploring sustainable healthcare. Innovations in health economics, social policy, and management. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J.; Lyu, R.; Zhong, L.; Wang, X. Socio-economic inequalities in health service utilization among Chinese rural migrant workers with New Cooperative Medical Scheme: A multilevel regression approach. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkonki, L.L.; Chola, L.L.; Tugendhaft, A.A.; Hofman, K.K. Modelling the cost of community interventions to reduce child mortality in South Africa using the Lives Saved Tool (LiST). BMJ Open 2017, 7, e011425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Human Resources for Health Collaborators. Measuring the availability of human resources for health and its relationship to universal health coverage for 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 2019, 399, 2129. [Google Scholar]

- Fradelos, E.C.; Alexandropoulou, C.-A.; Kontopoulou, L.; Alikari, V.; Papagiannis, D.; Tsaras, K.; Papathanasiou, I.V. The effect of hospital ethical climate on nurses’ work-related quality of life: A cross-sectional study. Nurs. Forum 2022, 57, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkar, B.; Pacheco, S.; Basu, R.; DeNicola, N. Association of Air Pollution and Heat Exposure With Preterm Birth, Low Birth Weight, and Stillbirth in the US: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020, 3, e208243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandel, N.; Chungong, S.; Omaar, A.; Xing, J. Health security capacities in the context of COVID-19 outbreak: An analysis of International Health Regulations annual report data from 182 countries. Lancet 2020, 395, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cluver, L.D.; Orkin, F.M.; Meinck, F.; Boyes, M.E.; Yakubovich, A.R.; Sherr, L. Can Social Protection Improve Sustainable Development Goals for Adolescent Health. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannouchos, T.V.; Ukert, B.; Vozikis, A.; Steletou, E.; Souliotis, K. Informal out-of-pocket payments experience and individuals’ willingness-to-pay for healthcare services in Greece. Health Policy 2021, 125, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Yan, Z.; Wen, S. Deep Learning and Artificial Intelligence in Sustainability: A Review of SDGs, Renewable Energy, and Environmental Health. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Phang, J.; Park, J.; Shen, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zorin, M.; Jastrzebski, S.; Fevry, T.; Katsnelson, J.; Kim, E.; et al. Deep Neural Networks Improve Radiologists’ Performance in Breast Cancer Screening. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2020, 39, 1184–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, F.; Ding, X.; Zheng, M. AlphaFold accelerates artificial intelligence powered drug discovery: Efficient discovery of a novel CDK20 small molecule inhibitor. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 1443–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenssgen, M.J. Aligning global health policy and research with sustainable development: A strategic market approach. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 32, 1876–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavridoglou, G.; Polyzos, N. Sustainability of Healthcare Financing in Greece: A Relation Between Public and Social Insurance Contributions and Delivery Expenditures. Inquiry 2022, 59, 469580221092829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.M.; Appolloni, A.; Cavallaro, F.; D’Adamo, I.; Di Vaio, A.; Ferella, F.; Gastaldi, M.; Ikram, M.; Kumar, N.M.; Martin, M.A.; et al. Development Goals towards Sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piran, M.; Sharifi, A.; Safari, M.M. Exploring the Roles of Education, Renewable Energy, and Global Warming on Health Expenditures. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharti, R.; Endalamaw, A.; Erku, D.; Wolka, E.; Nigatu, F.; Zewdie, A.; Assefa, Y. Continuity and care coordination of primary health care. A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 750. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Kim, C. Estimation of Association between Healthcare System Efficiency and Policy Factors for Public Health. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2674. [Google Scholar]

- Saruchera, F. Sustainability: A Concept in Flux? The Role of Multidisciplinary Insights in Shaping Sustainable Futures. Sustainability 2025, 17, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Key Policies | Focus Areas |

|---|---|---|

| Greece | National Health Action Plan, Primary Healthcare Reform, eHealth Strategy [41,42] | UHC, mental health, primary care, digital access |

| EU | EU4Health, Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan, Mental Health Strategy [43] | Health equity, NCDs, digitalization, pandemic response |

| Globally | GAP, UHC2030, Health Sector Strategies, HiAP [44] | Global coordination, health systems resilience |

| Healthcare Access Dimension | Description |

|---|---|

| Availability | Providence and the existence of medical resources, such as healthcare centers, staff, and services. |

| Accessibility | Easiness of reaching the healthcare center, taking into account the location of the center, the location of the patient, and the costs of transportation, distance, and duration. |

| Accommodation | How well healthcare services are organized to accept patients serve them, regarding office hours, appointment systems, walk-in facilities, and waiting times. |

| Affordability | Relationship between the healthcare services costs. |

| Acceptability | Relationship between provider and patient, regarding the personal characteristics, such as age, gender, ethnicity and religion, acceptance of these characteristics, and not discouraging the patient. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lakioti, E.; Pagonis, N.; Flegkas, D.; Itziou, A.; Moustakas, K.; Karayannis, V. Social Factors and Policies Promoting Good Health and Well-Being as a Sustainable Development Goal: Current Achievements and Future Pathways. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5063. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115063

Lakioti E, Pagonis N, Flegkas D, Itziou A, Moustakas K, Karayannis V. Social Factors and Policies Promoting Good Health and Well-Being as a Sustainable Development Goal: Current Achievements and Future Pathways. Sustainability. 2025; 17(11):5063. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115063

Chicago/Turabian StyleLakioti, Evangelia, Nikolaos Pagonis, Dimitrios Flegkas, Aikaterini Itziou, Konstantinos Moustakas, and Vayos Karayannis. 2025. "Social Factors and Policies Promoting Good Health and Well-Being as a Sustainable Development Goal: Current Achievements and Future Pathways" Sustainability 17, no. 11: 5063. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115063

APA StyleLakioti, E., Pagonis, N., Flegkas, D., Itziou, A., Moustakas, K., & Karayannis, V. (2025). Social Factors and Policies Promoting Good Health and Well-Being as a Sustainable Development Goal: Current Achievements and Future Pathways. Sustainability, 17(11), 5063. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115063