Does Financial Inclusion Have an Impact on Chinese Farmers’ Incomes? A Perspective Based on Total Factor Productivity in Agriculture

Abstract

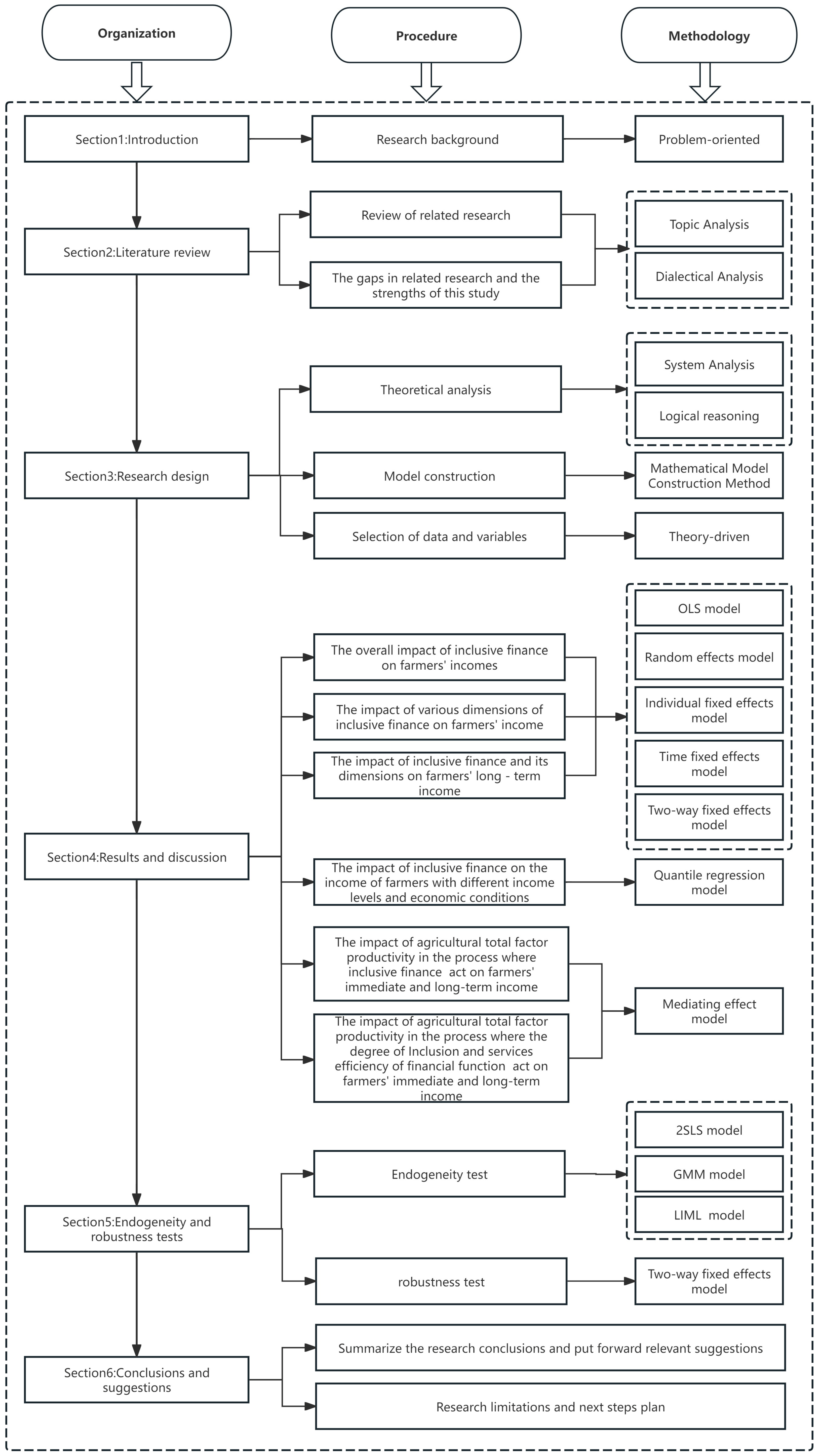

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Research Design

3.1. Theoretical Analysis

3.2. Model Construction

3.3. Data and Variables

- Explained variables

- Core explanatory variables

- Mediating variables

- Control variables

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. The Total Effect of Financial Inclusion Affecting Farmers’ Income

4.2. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.3. Transmission Mechanisms of the Impact of Financial Inclusion on Farmers’ Incomes

5. Endogeneity and Robustness Tests

6. Conclusions and Suggestions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Capital Development Fund. Building Inclusive Financial Sectors for Development; United Nations Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rafique, S. Implications of informal credit for policy development in India for building inclusive financial sectors. Asia Pac. Dev. J. 2006, 13, 101–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, D.; Mellor, M.; Dodds, L.; Affleck, A. Consulting the community: Advancing financial inclusion in Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2006, 26, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S. Structural change, growth and poverty reduction in Asia: Pathways to inclusive development. Dev. Policy Rev. 2006, 24, 51–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, J. Credit constraints and determinants of the cost of capital in Vietnamese manufacturing. Small Bus. Econ. 2007, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, C.N.; Jenkins, B. The Role of the Financial Services Sector in Expanding Economic Opportunity; Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative Report No. 19; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sriram, M.S. Productivity of rural credit: A review of issues and some recent literature. Int. J. Rural Manag. 2007, 3, 245–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, P. Improving Access to Finance for India’s Rural Poor; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dev, S.M. Financial inclusion: Issues and challenges. Econ. Political Wkly. 2006, 41, 4310–4313. [Google Scholar]

- Shetty, N.K. The microfinance promise in financial inclusion and welfare of the poor: Evidence from India. IUP J. Appl. Econ. 2008, 8, 174. [Google Scholar]

- Bebczuk, R.N. Financial Inclusion in Latin America and the Caribbean: Review and Lessons; Documentos de Trabajo No. 68; CEDLAS: La Plata, Argentina, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hol, S. The influence of the business cycle on bankruptcy probability. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2007, 14, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadanecz, B.; Jayaram, K. Measures of financial stability—A review. Irving Fish. Comm. Bull. 2008, 31, 365–383. [Google Scholar]

- Sarma, M. Index of Financial Inclusion; Working Paper No. 215; Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations: New Delhi, India, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gupte, R.; Venkataramani, B.; Gupta, D. Computation of financial inclusion index for India. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 37, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mialou, A.; Amidzic, G.; Massara, A. Assessing countries’ financial inclusion standing—A new composite index. J. Bank. Financ. Econ. 2017, 2, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Posso, A. Thinking inside the box: A closer look at financial inclusion and household income. J. Dev. Stud. 2019, 55, 1616–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, M. Index of Financial Inclusion—A Measure of Financial Sector Inclusiveness; Centre for International Trade and Development, School of International Studies Working Paper; Jawaharlal Nehru University: New Delhi, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Apparicio, P.; Abdelmajid, M.; Riva, M.; Shearmur, R. Comparing alternative approaches to measuring the geographical accessibility of urban health services: Distance types and aggregation-error issues. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2008, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, R.U. Financial inclusion and human capital in developing Asia: The Australian connection. Third World Q. 2012, 33, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisaiti, G.; Liu, L.; Xie, J.; Yang, J. An empirical analysis of rural farmers’ financing intention of inclusive finance in China: The moderating role of digital finance and social enterprise embeddedness. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2019, 119, 1535–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.A.; Inaba, K. Does financial inclusion reduce poverty and income inequality in developing countries? A panel data analysis. J. Econ. Struct. 2020, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorulmaz, R. An analysis of constructing global financial inclusion indices. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2018, 18, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cámara, N.; Tuesta, D. Measuring financial inclusion: A multidimensional index. BBVA Res. Pap. 2014, 14, 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Dungey, M.; Tchatoka, F.D.; Yanotti, M.B. Using multiple correspondence analysis for finance: A tool for assessing financial inclusion. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2018, 59, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.H.; Chuc, A.T.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Financial inclusion and its impact on financial efficiency and sustainability: Empirical evidence from Asia. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2019, 19, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanzhi, T.; Yunzhong, L.I.; Chengfang, Y. Evaluation of provincial digital inclusive finance and rural revitalization and its coupling synergy analysis. Econ. Geogr. 2021, 41, 187–195. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, Y. The effect of green finance on energy sustainable development: A case study in China. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2021, 57, 3435–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Gong, K.; Luo, S.; Xu, G. Inclusive finance, human capital and regional economic growth in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowowe, B. The effects of financial inclusion on agricultural productivity in Nigeria. J. Econ. Dev. 2020, 22, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, G. Digital financial inclusion and farmers’ vulnerability to poverty: Evidence from rural China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegbite, O.O.; Machethe, C.L. Bridging the financial inclusion gender gap in smallholder agriculture in Nigeria: An untapped potential for sustainable development. World Dev. 2020, 127, 104755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abor, J.Y.; Amidu, M.; Issahaku, H. Mobile telephony, financial inclusion and inclusive growth. J. Afr. Bus. 2018, 19, 430–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Tong, A.; Hu, Z.; Wang, Y. The impact of the inclusive financial development index on farmer entrepreneurship. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlanga, D.; Dunga, S.H.; Moloi, T. Financial inclusion and poverty alleviation among smallholder farmers in Zimbabwe. Eurasian J. Econ. Financ. 2020, 8, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Fang, H.; Gong, X.; Wang, F. Inclusive finance, industrial structure upgrading and farmers’ income: Empirical analysis based on provincial panel data in China. PLoS ONE 2020, 16, e0258860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Liao, G.; Wang, J. Spatial spillover effect and threshold effect of digital financial inclusion on farmers’ income growth—Based on provincial data of China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Tang, L.; Zhou, X.; Tang, D.; Boamah, V. Research on the effect of rural inclusive financial ecological environment on rural household income in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; He, G.; Turvey, C.G. Inclusive finance, farm households entrepreneurship, and inclusive rural transformation in rural poverty-stricken areas in China. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2021, 57, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, R.; Arango, C.; Lomboy, C.G.; Box, S. Financial inclusion to build economic resilience in small-scale fisheries. Mar. Policy 2020, 118, 103982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Guo, L. Financial technology, inclusive finance and bank performance. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 60, 104872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wang, X.; Wu, T.; Deng, W. Reducing farmers’ poverty vulnerability in China: The role of digital financial inclusion. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2023, 27, 1445–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peprah, J.A.; Koomson, I.; Sebu, J.; Bukari, C. Improving productivity among smallholder farmers in Ghana: Does financial inclusion matter? Agric. Financ. Rev. 2021, 81, 481–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ning, Z.; Shu, Y.; Riti, M.K.J.; Riti, J.S. ICT interaction with trade, FDI and financial inclusion on inclusive growth in top African nations ranked by ICT development. Telecommun. Policy 2023, 47, 102490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.U.; Ahmed, Z.; Ramzan, A.; Shabbir, M.N.; Bashir, Z.; Khan, F.N. Financial inclusion and monetary policy effectiveness: A sustainable development approach of developed and under-developed countries. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Financial inclusion and urban–rural income inequality: Long-run and short-run relationships. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2020, 56, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Yajuan, L.; Khan, S. Promoting Chin’s inclusive finance through digital financial services. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2022, 23, 984–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, L.Y.; Tai, H.T.; Tan, G.S. Digital financial inclusion: A gateway to sustainable development. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L. Effect of digital inclusive finance on common prosperity and the underlying mechanisms. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 91, 102940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzahid, E.; Elouaourti, Z. Financial inclusion, mobile banking, informal finance and financial exclusion: Micro-level evidence from Morocco. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2021, 48, 1060–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ning, M.; Yang, C. Evaluation of the mechanism and effectiveness of digital inclusive finance to drive rural industry prosperity. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Huang, H.; Kong, X.; Zhu, K. Can Digital Inclusive Finance Improve the Financial Performance of SMEs? Sustainability 2023, 15, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, J. The impact of digital financial inclusion on the level of agricultural output. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Fan, Z.; Andrianarimanana, M.H.; Yu, S. Impact of Climate Risk on Farmers’ Income: The Moderating Role of Digital Inclusive Finance. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 33, 2799–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H. Digital Inclusive Finance, Digital Availability and the Relative Poverty Vulnerability of Farmers. Front. Econ. Manag. 2022, 3, 165–179. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, R.; Zeng, Y.; Huang, Q. Research on the impact of digital inclusive finance on the performance of rural returnee entrepreneurs in China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H. Digital inclusive finance, multidimensional education, and farmers’ entrepreneurial behavior. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 1, 6541437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Peng, B. The impact of digital financial inclusion on green and low-carbon agricultural development. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qi, Y.; Li, Y. How does digital inclusive finance influence non-agricultural employment among the rural labor force?—Evidence from micro-data in China. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zheng, X.; Yang, L. Does digital inclusive finance narrow the urban-rural income gap through primary distribution and redistribution? Sustainability 2022, 14, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M.; Li, W.; Teo, B.S.X.; Othman, J. Can China’s digital inclusive finance alleviate rural poverty? An empirical analysis from the perspective of regional economic development and an income gap. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutassey, V.A.; Nomlala, B.C.; Sibanda, M. Enhancing Inclusive Finance in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Collaborative Role of Economic Freedom and Innovative Facilities. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2025, 67, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, R. Economic growth, financial deepening and financial inclusion. In Dynamics of Indian Banking: Views and Vistas; Atlantic Books: New Delhi, India, 2008; pp. 92–120. [Google Scholar]

- Swamy, V. Financial inclusion, gender dimension, and economic impact on poor households. World Dev. 2014, 56, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Gupta, H. Financial inclusion and farmers: Association between status and demographic variables. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2019, 8, 5868–5879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrin, S.; Haider, M.Z.; Islam, M.S. Impact of financial inclusion on technical efficiency of paddy farmers in Bangladesh. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2017, 77, 484–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, A.; Mutandwa, L.; Le Roux, P. A review of determinants of financial inclusion. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2018, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, S.; Gul, R.; Ullah, S.; Waheed, A.; Naeem, M. Empirical nexus between financial inclusion and carbon emissions: Evidence from heterogeneous financial economies and regions. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Gao, T.; Shi, X.; Chen, X.; Mu, K. The impact and heterogeneity analysis of digital financial inclusion on non-farm employment of rural labor. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2023, 21, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cnaan, R.A.; Moodithaya, M.S.; Handy, F. Financial inclusion: Lessons from rural South India. J. Soc. Policy 2012, 41, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Xu, G. Can Digital Financial Inclusion Promote the Sustainable Growth of Farmers’ Income?—An Empirical Analysis Based on Panel Data from 30 Provinces in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirir, S.A. Performing a quantile regression to explore the financial inclusion in emerging countries and lessons african countries can learn from them. Eur. J. Dev. Stud. 2022, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, G.; He, C.; Zhang, P. Rural banking in China: Geographically accessible but still financially excluded? Reg. Stud. 2017, 51, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satpathy, I.; Patnaik, B.C.M.; Das, P.K. Transformation from class banking to mass banking through inclusive finance: A paradigm shift. Asian Soc. Sci. 2014, 10, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi, F.; Kong, Y.; Gyimah, K.N. Financial inclusion, competition and financial stability: New evidence from developing economies. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, A.G.; Schwabe, R. Bank competition and financial inclusion: Evidence from Mexico. Rev. Ind. Organ. 2019, 55, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koomson, I.; Villano, R.A.; Hadley, D. Effect of financial inclusion on poverty and vulnerability to poverty: Evidence using a multidimensional measure of financial inclusion. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 149, 613–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatun, T.; Afroze, S. Relationship between real GDP and labour & capital by applying the Cobb-Douglas production function: A comparative analysis among selected Asian countries. J. Bus. Stud. 2016, 37, 113–129. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, A.N.; Demsetz, R.S.; Strahan, P.E. The consolidation of the financial services industry: Causes, consequences, and implications for the future. J. Bank. Financ. 1999, 23, 135–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duy, V.Q.; D’Haese, M.; Lemba, J.; Hau, L.L.; D’Haese, L. Determinants of household access to formal credit in the rural areas of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Afr. Asian Stud. 2012, 11, 261–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nin-Pratt, A.; Yu, B. Getting implicit shadow prices right for the estimation of the Malmquist index: The case of agricultural total factor productivity in developing countries. Agric. Econ. 2010, 41, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipi, T.; Rehber, E. Measuring technical efficiency and total factor productivity in agriculture: The case of the South Marmara region of Turkey. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 2006, 49, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jiang, Q. Rural Inclusive Finance and Agricultural Carbon Reduction: Evidence from China. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, A.D.; Rosenzweig, M.R. Learning by doing and learning from others: Human capital and technical change in agriculture. J. Political Econ. 1995, 103, 1176–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Liu, C.; Souleles, N.S. The reaction of consumer spending and debt to tax rebates—Evidence from consumer credit data. J. Political Econ. 2007, 115, 986–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, G.; Onchan, T.; Raparla, T. Collateral, guaranties and rural credit in Developing countries: Evidence from Asia. Agric. Econ. 1988, 2, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikdar, P.; Kumar, A. Payment bank: A catalyst for financial inclusion. Asia-Pac. J. Manag. Res. Innov. 2016, 12, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.L.; Ruttan, V.W. Why are farms so small? World Dev. 1994, 22, 691–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Qinyang, L.; Jiajia, H. Does digital technology enhance the global value chain position? Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2024, 24, 856–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, X. Digital revolution and rural family income: Evidence from China. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 94, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhou, J. Digital literacy, farmers’ income increase and rural Internal income gap. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Bin, C.; Siting, L.; Gaoke, L. The impact of financial institutions’ cross-shareholdings on risk-taking. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 92, 1526–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqib, S.E.; Ahmad, M.M.; Panezai, S.; Rana, I.A. An empirical assessment of farmers’ risk attitudes in flood-prone areas of Pakistan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 18, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, R.; Shivakoti, G.P.; Zulfiqar, F.; Kamran, M.A. Farm risks and uncertainties: Sources, impacts and management. Outlook Agric. 2016, 45, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Key Points | Comparison |

|---|---|---|

| United Nations Publications (2006) [1] | Inclusive finance can effectively serve all segments of society, especially those with low incomes. | The concept of financial inclusion was explicitly mentioned for the first time, laying a theoretical foundation. |

| Rafique S. (2006) [2]; Fuller D. et al. (2006) [3]; Cook S. (2006) [4]. | Improved financial inclusion infrastructure improves farmers’ incomes. | A Theoretical Framework for Financial Inclusion and Farmers’ Income from the Perspective of Infrastructure Improvement, but with limitations. |

| Basu P. (2006) [8]; Dev S.M. (2006) [9]; Sutton C.N. et al. (2007) [6]; Rand J. (2007) [5]; Sriram M.S. (2007) [7]. | Inclusive finance can smooth out the risks farmers face to realize income gains. Inclusive finance can ease credit constraints to realize farmers’ income growth. | A Theoretical Framework for Financial Inclusion and Farmers’ Income from the perspective of financial products and services expands theoretical perspectives. |

| Author | Key Points | Comparison |

|---|---|---|

| Shetty N.K. (2008) [10]; Bebczuk R.N. (2008) [11]; Hol S. (2007) [12]; Gadanecz B. (2008) [13]. | Measuring inclusive finance using the ratio of financial assets to physical assets, the ratio of money supply to GDP, and the ratio of private sector bank lending to GDP. | A single indicator cannot comprehensively measure financial inclusion. |

| Sarma M. (2008) [14] | For the first time, the Integrated Financial Inclusion Index (IFI) was constructed using three indicators: bank penetration, bank service availability, and service utilization efficiency. | The IFI index lays the foundation for scholars to utilize a variety of indicators to construct financial inclusion. |

| Gupte R. et al. (2012) [15] | Building on Sarma (2008), the transaction costs of banking services are further considered. | Expanded IFI index. However, the relevant data in the IFI constructed indicators are difficult to obtain in some countries, and the measurement is at the national level. |

| Mialou A. et al. (2017) [16]; Zhang Q. et al. (2019) [17]. | Measuring the financial inclusion index using the number of ATMs, the number of branches of ODCs, the total number of residents lending to ODCs, and the number of residents borrowing from ODCs, dummy variable form. | Financial inclusion measures are selected from more accessible indicators, more micro perspectives, and more comprehensive information. |

| Sarma M. (2008) [14]; Apparicio P. (2008) [19]; Sarma M. (2012) [18]. | Measuring financial inclusion using the mean Euclidean distance method. | Capable of capturing the spatial distance characterization of financial inclusion, but may mask complementarities between indicators and be computationally complex. |

| Arora R.U. (2012) [20] | Measuring financial inclusion using simple geometric averages. | Simple to calculate, but poorly interpreted for indices constructed using multiple indicators. |

| Aisaiti G. et al. (2019) [21]; Omar M.A. et al. (2020) [22]. | Measuring financial inclusion using factor analysis. | It can be downscaled and reveal underlying structure, and can handle high correlation between indicators. But the prerequisite assumptions, such as normality and sufficient correlation, have to be satisfied. Meanwhile, factor naming and interpretation rely on subjective judgment. |

| Cámara N. (2014) [24]; Yorulmaz R. (2018) [23]; Dungey M. (2018) [25]; Le T.H. (2019) [26]. | Measuring financial inclusion using principal component analysis. | Completely dependent on the data and without subjective assumptions, it can effectively eliminate the problem of multicollinearity. However, this method is sensitive to data distribution and also suffers from the problem of omitting secondary information. |

| Yanzhi T. (2021) [27]; Zhang B. (2021) [28]. | Measuring financial inclusion using the entropy approach. | Determines weights based entirely on data, avoiding the influence of subjective factors. It is robust to outliers and insensitive to data distribution. At the same time, the entropy value method can maximize the reflection of information and improve the efficiency of the use of information in the indicators. |

| Zhou G. (2020) [29]; Fowowe B. (2020) [30]; Aisaiti G. (2019) [21]; Adegbite O.O. et al. (2020) [32]; Abor J.Y.et al.(2018) [33]. | Exploring the impact of financial inclusion on farmers’ incomes from a capacity to use perspective. | Shifting the study of the impact of financial inclusion on farmers’ incomes from the direct to the indirect level. |

| Wang X. et al. (2020) [31]; Jiang L. et al. (2019) [34]; Mhlanga D. (2020) [35]. | Digital financial inclusion can effectively contribute to farmers’ income growth. | Focusing on the innovative potential of technology-driven inclusive financial development, it reveals the pathways of inclusive finance to increase farmers’ incomes when augmented by digital technology. |

| Author | Key Points | Comparison |

|---|---|---|

| Fowowe B. (2020) [30]; Pomeroy R. et al. (2020) [40]; Huang Y. (2020) [46]; Peprah J.A. et al. (2021) [43]; Liu G. et al. (2020) [36]; Liu T. et al. (2021) [39]; Arshad M.U. et al. (2021) [45]; Li Y. et al. (2022) [37]; Ge H. et al. (2022) [38]; Yang B. et al. (2023) [42]; Wang W. et al. (2023) [44]; Zhu K. et al. (2024) [41]. | Exploring the impact of inclusive finance on farmers’ incomes in terms of the level of regional economic development, industrial structure, non-farm employment, agricultural productivity, international trade, fiscal and monetary policies, urban–rural factor flows, and resource allocation efficiency. | The research horizon expands from focusing on the supply and demand side of financial inclusion to exploring the impact of financial inclusion on farmers’ incomes from various pathways in the economy. |

| Ezzahid E. et al. (2021) [50]; Liu Z. et al. (2021) [57];Hasan M.M. et al. (2022) [47]; Tay L.Y.et al.(2022) [48]; Qian H. (2022) [55]; Zhang L. et al. (2023) [51]; Yu W. et al. (2023) [52]; Xu S. et al. (2023) [53]; Liu Y. et al. (2023) [58]; Zhang C. et al. (2024) [49]; Qin Z. et al. (2024) [54]; Chen Y. et al. (2024) [56]; Wang Y. et al. (2024) [59]. | Exploring the impact of inclusive finance on farmers’ incomes in terms of digital account penetration, mobile payment frequency, online credit approval efficiency, digital insurance participation rate, bio-digital technology use, and the degree of business digitization. | The indirect impact of financial inclusion on farmers’ incomes extends from the perspective of farmers’ ability to use it (human capital, risk appetite, and social networks) to the state of economic development of a country or a region. |

| Zhao H. et al. (2022) [60]; Xiong M. et al. (2022) [61]; Nutassey V.A. et al. (2025) [62]. | The digital divide and the inadequacy of digital infrastructure have prevented the emergence of inclusive finance from realizing the effects of digital technology on farmers’ incomes. | Provide a digital divide and infrastructure development level explanation for the inability of financial inclusion to enhance farmers’ incomes through the development of digital technologies. |

| Mohan R. (2008) [63]; Swamy V. (2014) [64]. | Income-level differences in the impact of financial inclusion on farmers’ incomes. | A single indicator dimension does not capture the differences in the impact of financial inclusion on farmers’ incomes in other dimensions. |

| Kumar A. et al. (2019) [65]; Afrin S. et al. (2017) [66]; Sanderson A. et al. (2018) [67]; Hussain S. et al. (2023) [68]; Ren J. et al. (2023) [69]. | Examining the Heterogeneity of Financial Inclusion on Farmers’ Income from Environmental and Financial Literacy Dimensions. | Expanded dimensions of heterogeneity analysis of financial inclusion on farmers’ income. |

| Arora R.U. (2012) [20]; Cnaan R.A. (2012) [70]. | Subgroup regression to explore the heterogeneity of financial inclusion on farmers’ income. | The criteria for determining grouping are often subjective and may lead to biased results. Moreover, it is not possible to deal with continuous heterogeneity. |

| Li Y. et al. (2022) [37]; Peprah, J.A. et al. (2021) [43]; Xia Y. et al. (2025) [71]. | Interactivity modeling to explore the heterogeneity of financial inclusion on farmers’ income. | Compensates for the shortcomings of grouped regressions, but does not fully reveal the heterogeneity of the distribution, and there may also be a risk of multicollinearity. |

| Afrin S. et al. (2017) [66]; Peprah J.A. et al. (2021) [43]; Dirir, S.A. et al. (2022) [72]. | Quantile regression modeling to explore the heterogeneity of financial inclusion on farmers’ income. | It can fully reveal distributional heterogeneity, is robust to distributions with extreme values such as income, and can accurately measure differences in the impact of financial inclusion across quartile levels. |

| Stage | Research Topics | Comparison/Marginal Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| The first stage | The concept of inclusive finance introduction and the impact of inclusive finance on farmers’ income theoretical foundation. | Contribution: The research on the impact of financial inclusion on farmers’ income has built up a theoretical framework at this stage. Weaknesses:

|

| The second stage | The rise of measurement and empirical evidence of financial inclusion. | Contributions:

|

| The third stage | A multidimensional perspective on the impact of financial inclusion on farmers’ incomes. | Contribution: Research on financial inclusion and farmers’ income has entered a phase of in-depth studies with multiple dimensions and methodologies, including direct impact, indirect impact, and heterogeneity. Weaknesses:

|

| My study | The relationship between financial inclusion and the two dimensions of financial inclusion (the degree of inclusion and the service efficiency of the financial function) and farmers’ incomes is discussed, and the impact of total factor productivity in agriculture on this relationship is further discussed. | Contribution:

|

| Primary Indicators | Secondary Indicators | Tertiary Indicators | Description of Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusive finance | Degree of inclusion | Population density of banking and financial institutions | Number of outlets/resident population |

| Density of workers in banking and financial institutions | Number of employees/resident population | ||

| Geographic density of banking and financial institutions | Number of outlets/land area | ||

| Geographic density of workers in banking and financial institutions | Number of practitioners/land area | ||

| Population density of insurance-based financial institutions | Number of outlets/ resident population | ||

| Population density of employees of insurance-based financial institutions | Number of employees/resident population | ||

| Geographic density of insurance-based financial institutions | Number of outlets/land area | ||

| Geographic density of employees of insurance-based financial institutions | Number of practitioners/land area | ||

| Population density of microfinance companies | Number of outlets/resident population | ||

| Geographic density of microfinance companies | Number of outlets/land area | ||

| Insurance claims per capita | Expenditure on insurance claims/ resident population | ||

| Loans per capita | Loan balance/resident population | ||

| Deposits per capita | Savings balance/resident population | ||

| Agricultural loan ratio | Balance of agricultural loans/all loans | ||

| Financial function service efficiency | Various loan balances | Balance of all loans to financial institutions | |

| Various deposit balances | Balance of all deposits in financial institutions | ||

| Loan level | Various loan balances/GDP | ||

| Deposit level | Various deposit balances/GDP | ||

| Non-performing loan ratio | Non-performing loans/all loan balances | ||

| Insurance depth | Insurance premium income/GDP | ||

| insurance density | Insurance premium income/ resident population | ||

| Year-on-year rate of change in premium income | Value of change in insurance income/ previous year’s insurance income |

| VarName | VarSymbol | Obs | Mean | Median | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmers’ Income | IN | 300 | 1.604 | 1.471 | 0.644 | 0.696 | 3.841 |

| Financial Inclusion | FIN | 300 | 0.106 | 0.076 | 0.082 | 0.025 | 0.392 |

| Degree of Inclusion | FPN | 300 | 0.084 | 0.058 | 0.083 | 0.006 | 0.840 |

| Financial Function Service Efficiency | FGN | 300 | 0.114 | 0.071 | 0.105 | 0.021 | 0.457 |

| Agricultural Total Factor Productivity | TFP | 300 | 1.641 | 1.395 | 0.882 | 6.926 | 0.293 |

| Urbanization | UR | 300 | 0.624 | 0.610 | 0.112 | 0.402 | 0.941 |

| Farmers’ Investment | FTZ | 300 | 5.141 | 4.524 | 3.199 | 1.864 | 17.543 |

| Agricultural Machinery Use | NJ | 300 | 0.423 | 0.354 | 0.219 | 0.136 | 1.152 |

| Fertilizer Use | HF | 300 | 1.929 | 0.410 | 4.783 | 0.014 | 31.872 |

| Level of Economic Development | GDP | 300 | 0.116 | 0.056 | 0.204 | 0.002 | 1.643 |

| VAR | OLS | RE | FE | FE | FE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| FIN | 3.242 *** | 3.017 *** | 2.986 *** | 3.534 *** | 1.226 *** |

| (0.401) | (0.546) | (0.583) | (0.335) | (0.348) | |

| UR | 2.269 *** | 6.282 *** | 7.617 *** | 1.373 *** | −1.053 ** |

| (0.272) | (0.372) | (0.394) | (0.237) | (0.432) | |

| FTZ | −0.019 * | −0.034 *** | −0.030 *** | 0.006 | 0.016 *** |

| (0.010) | (0.008) | (0.007) | (0.009) | (0.005) | |

| NJ | −0.070 | −0.458 *** | −0.343 ** | 0.156 | −0.106 |

| (0.124) | (0.140) | (0.139) | (0.105) | (0.078) | |

| HF | −0.003 | −0.002 | −0.011 | −0.009 * | −0.001 |

| (0.006) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.005) | (0.004) | |

| GDP | −0.337 ** | 0.068 | 0.107 | −0.390 *** | 0.043 |

| (0.139) | (0.089) | (0.083) | (0.119) | (0.048) | |

| Cons | 0.017 | −2.269 *** | −3.151 *** | 0.341 ** | 2.093 *** |

| (0.173) | (0.264) | (0.267) | (0.146) | (0.275) | |

| Province fixed effects | yes | no | yes | ||

| Year fixed effects | no | yes | yes | ||

| N | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 |

| 0.474 | 0.909 | 0.651 | 0.974 |

| VAR | T | T + 1 | T + 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| FIN | 1.085 *** | 1.005 *** | ||||||

| (0.349) | (0.335) | |||||||

| FPN | 0.403 *** | 0.329 *** | 0.295 ** | |||||

| (0.131) | (0.123) | (0.114) | ||||||

| FGN | 0.950 ** | 1.018 * | 1.127 * | |||||

| (0.478) | (0.550) | (0.609) | ||||||

| control variable | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Cons | 2.224 *** | 2.160 *** | 1.981 *** | 2.104 *** | 2.007 *** | 1.900 *** | 2.019 *** | 1.919 *** |

| (0.271) | (0.283) | (0.283) | (0.279) | (0.294) | (0.293) | (0.288) | (0.306) | |

| Province fixed effects | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Year fixed effects | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| N | 300 | 300 | 270 | 270 | 270 | 240 | 240 | 240 |

| 0.973 | 0.973 | 0.977 | 0.977 | 0.977 | 0.982 | 0.981 | 0.981 | |

| Area | Variant | Timing | Obs | Q(10) | Q(25) | Q(50) | Q(75) | Q(90) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| full sample | FIN | T | 300 | 1.247 *** | 1.201 *** | 1.676 *** | 3.406 *** | 6.135 *** |

| (0.358) | (0.406) | (0.499) | (0.641) | (0.993) | ||||

| T + 1 | 270 | 1.076 ** | 1.448 *** | 1.961 *** | 4.104 *** | 6.719 *** | ||

| (0.473) | (0.437) | (0.502) | (0.742) | (1.100) | ||||

| T + 2 | 240 | 1.213 ** | 1.605 *** | 2.107 *** | 3.942 *** | 5.864 *** | ||

| (0.548) | (0.470) | (0.529) | (0.719) | (1.168) | ||||

| FPN | T | 300 | 0.772 ** | 1.730 *** | 3.045 *** | 5.400 *** | 9.118 *** | |

| (0.350) | (0.372) | (0.452) | (0.429) | (0.760) | ||||

| T + 1 | 270 | 0.996 *** | 1.455 *** | 2.778 *** | 5.867 *** | 9.525 *** | ||

| (0.354) | (0.361) | (0.457) | (0.485) | (0.960) | ||||

| T + 2 | 240 | 1.020 ** | 1.246 *** | 1.916 *** | 7.069 *** | 10.563 *** | ||

| (0.431) | (0.424) | (0.455) | (0.569) | (0.939) | ||||

| FGN | T | 300 | 0.553 * | 0.357 | 0.714 ** | 1.444 *** | 3.549 *** | |

| (0.296) | (0.303) | (0.353) | (0.497) | (0.955) | ||||

| T + 1 | 270 | 0.740 ** | 0.425 | 0.813 ** | 1.958 *** | 3.635 *** | ||

| (0.362) | (0.361) | (0.389) | (0.538) | (0.915) | ||||

| T + 2 | 240 | 0.866 ** | 0.499 | 0.718 * | 2.426 *** | 4.285 *** | ||

| (0.373) | (0.384) | (0.413) | (0.509) | (1.079) |

| Area | Variant | Timing | Obs | Q (10) | Q (25) | Q (50) | Q (75) | Q (90) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| economically developed area | FIN | T | 150 | 3.724 *** | 3.977 *** | 3.998 *** | 5.040 *** | 5.677 *** |

| (0.391) | (0.491) | (0.652) | (0.794) | (1.112) | ||||

| T + 1 | 135 | 4.291 *** | 4.124 *** | 4.558 *** | 6.157 *** | 6.040 *** | ||

| (0.412) | (0.458) | (0.676) | (0.860) | (1.156) | ||||

| T + 2 | 120 | 4.724 *** | 4.604 *** | 5.177 *** | 6.538 *** | 6.359 *** | ||

| (0.450) | (0.547) | (0.749) | (0.704) | (1.172) | ||||

| FPN | T | 150 | 2.738 *** | 3.130 *** | 5.104 *** | 4.975 *** | 8.199 *** | |

| (0.505) | (0.716) | (0.514) | (0.798) | (1.092) | ||||

| T + 1 | 135 | 3.201 *** | 2.609 *** | 5.536 *** | 5.531 *** | 8.265 *** | ||

| (0.427) | (0.772) | (0.526) | (0.901) | (1.182) | ||||

| T + 2 | 120 | 3.057 *** | 2.538 *** | 6.083 *** | 5.950 *** | 8.860 *** | ||

| (0.707) | (0.806) | (0.620) | (1.027) | (1.362) | ||||

| FGN | T | 150 | 2.595 *** | 2.500 *** | 3.225 *** | 3.721 *** | 4.215 *** | |

| (0.399) | (0.384) | (0.564) | (0.720) | (0.824) | ||||

| T + 1 | 135 | 2.960 *** | 3.038 *** | 3.176 *** | 3.857 *** | 3.586 *** | ||

| (0.357) | (0.420) | (0.554) | (0.799) | (1.002) | ||||

| T + 2 | 120 | 3.376 *** | 3.292 *** | 3.338 *** | 4.812 *** | 3.607 *** | ||

| (0.378) | (0.434) | (0.604) | (0.895) | (1.369) | ||||

| economically less developed area | FIN | T | 150 | 0.351 | 0.197 | −0.073 | −0.434 | 0.314 |

| (0.531) | (0.535) | (0.756) | (0.887) | (0.859) | ||||

| T + 1 | 135 | 0.376 | 0.096 | 0.531 | 0.241 | 0.400 | ||

| (0.545) | (0.589) | (0.766) | (0.812) | (0.916) | ||||

| T + 2 | 120 | 0.539 | 0.474 | 0.995 | −0.260 | −0.453 | ||

| (0.503) | (0.558) | (0.761) | (0.907) | (1.237) | ||||

| FPN | T | 150 | 0.709 * | 1.436 *** | 1.989 *** | 3.444 *** | 2.335 *** | |

| (0.365) | (0.433) | (0.624) | (0.718) | (0.521) | ||||

| T + 1 | 135 | 1.016 ** | 1.534 *** | 1.315 ** | 3.916 *** | 2.602 *** | ||

| (0.399) | (0.441) | (0.526) | (0.671) | (0.682) | ||||

| T + 2 | 120 | 0.984 *** | 1.425 *** | 1.962 *** | 0.834 | 3.481 *** | ||

| (0.350) | (0.394) | (0.518) | (0.822) | (0.779) | ||||

| FGN | T | 150 | 0.074 | −0.206 | −0.321 | −0.307 | −0.530 | |

| (0.364) | (0.414) | (0.547) | (0.621) | (0.551) | ||||

| T + 1 | 135 | −0.017 | −0.055 | −0.007 | −0.302 | −0.198 | ||

| (0.426) | (0.400) | (0.557) | (0.551) | (0.679) | ||||

| T + 2 | 120 | −0.148 | −0.138 | 0.095 | −0.316 | −0.683 | ||

| (0.419) | (0.427) | (0.551) | (0.607) | (0.761) |

| T | T + 1 | T + 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAR | TFP | IN | IN | IN |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| TFP | 0.019 * | 0.025 *** | 0.016 | |

| (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.010) | ||

| FIN | 3.781 * | 1.154 *** | 0.954 *** | 0.897 *** |

| (2.239) | (0.348) | (0.348) | (0.340) | |

| control variables | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Cons | −2.549 | 2.141 *** | 2.089 *** | 2.020 *** |

| (1.766) | (0.274) | (0.282) | (0.300) | |

| N | 300 | 300 | 270 | 240 |

| 0.420 | 0.974 | 0.978 | 0.982 | |

| VAR | T | T + 1 | T + 2 | T | T + 1 | T + 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFP | IN | IN | IN | TFP | IN | IN | IN | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| TFP | 0.019 ** | 0.026 *** | 0.018 * | 0.022 ** | 0.027 *** | 0.019 * | ||

| (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.010) | |||

| FPN | 1.478 * | 0.375 *** | 0.287 ** | 0.263 ** | ||||

| (0.835) | (0.131) | (0.123) | (0.115) | |||||

| FGN | 1.638 | 0.914 * | 0.889 | 0.947 | ||||

| (3.039) | (0.475) | (0.543) | (0.613) | |||||

| control variables | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Cons | −2.197 | 2.266 *** | 2.201 *** | 2.135 *** | −2.132 | 2.206 *** | 2.121 *** | 2.063 *** |

| (1.729) | (0.270) | (0.277) | (0.294) | (1.797) | (0.281) | (0.292) | (0.313) | |

| N | 300 | 300 | 270 | 240 | 300 | 300 | 270 | 240 |

| 0.421 | 0.974 | 0.978 | 0.982 | 0.414 | 0.973 | 0.977 | 0.981 | |

| VAR | 2SLS | GMM | LIML |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| First-stage regressions | FIN | FIN | FIN |

| IVI_FIN | 0.531 *** | 0.531 *** | 0.531 *** |

| (0.142) | (0.142) | (0.142) | |

| F-value | 13.97 | 13.97 | 13.97 |

| First-order autocorrelation p-value | 0.164 | ||

| Second-order autocorrelation p-value | 0.379 | ||

| Second-stage regressions | IN | IN | IN |

| FIN | 0.457 *** | 0.457 *** | 0.457 *** |

| (0.155) | (0.155) | (0.155) | |

| Control variable | yes | yes | yes |

| Province fixed effects | yes | yes | yes |

| Year fixed effects | yes | yes | yes |

| Endogeneity test | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| First-order autocorrelation p-value | 0.395 | ||

| Second-order autocorrelation p-value | 0.363 | ||

| N | 270 | 270 | 270 |

| −0.648 | −0.648 | −0.648 |

| Primary Indicators | Secondary Indicators | Tertiary Indicators | Description of Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital technology | Digital foundation | Rural delivery line density | Rural delivery routes/area size |

| Long-haul fiber optic cable line density | Fiber optic cable length/area size | ||

| Density of cell phone base stations | Number of cell phone base stations/area size | ||

| Digital network | Rural broadband Internet penetration | Number of rural broadband Internet subscribers/number of resident population | |

| Rural cell phone penetration | Mobile telephones per 100 inhabitants in rural areas | ||

| Rural computer penetration rate | Computers per 100 inhabitants in rural areas | ||

| Risk | Financial risk | Formal loan repayment burden ratio | Loans to farmers from financial institutions/ Gross disposable income of farmers |

| Contingency funding coverage | Available cash/necessary expenditures | ||

| Natural risk | Coefficient of variation of precipitation | Standard deviation of precipitation in the past five years/average precipitation in the past five years | |

| Density of climate disasters | Area of agricultural land affected by severe weather Area of agricultural land | ||

| Density of biological disasters | Area of agricultural land affected by pests and diseases/Area of agricultural land | ||

| Market risk | Price coefficient of variation | Number of rural broadband Internet subscribers/number of resident population | |

| Market concentration index | Standard deviation of wholesale prices of agricultural commodities in the past five years/Average wholesale prices of agricultural commodities in the past five years |

| VAR | Replacement of Explanatory Variables | Replacement Samples | Replacement of Explanatory Variables | Add Control Variables of Digital Technology | Add Control Variables of Risk | Add Control Variables of Digital Technology and Risk | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| FIN | 0.665 ** | 1.068 *** | 0.838 *** | 1.252 *** | 0.914 *** | ||

| (0.267) | (0.372) | (0.285) | (0.334) | (0.282) | |||

| L.FIN | 0.859 ** | ||||||

| (0.339) | |||||||

| L2.FIN | 0.816 *** | ||||||

| (0.310) | |||||||

| Control variable | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Province fixed effects | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Year fixed effects | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Cons | 1.921 *** | 2.035 *** | 2.122 *** | 2.157*** | 1.805 *** | 1.672 *** | 1.651 *** |

| (0.295) | (0.423) | (0.394) | (0.396) | (0.314) | (0.374) | (0.313) | |

| N | 300 | 260 | 270 | 240 | 300 | 300 | 300 |

| 0.975 | 0.973 | 0.978 | 0.984 | 0.979 | 0.971 | 0.979 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, B.; Zhu, S. Does Financial Inclusion Have an Impact on Chinese Farmers’ Incomes? A Perspective Based on Total Factor Productivity in Agriculture. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5034. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115034

Huang B, Zhu S. Does Financial Inclusion Have an Impact on Chinese Farmers’ Incomes? A Perspective Based on Total Factor Productivity in Agriculture. Sustainability. 2025; 17(11):5034. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115034

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Bingrou, and Shubin Zhu. 2025. "Does Financial Inclusion Have an Impact on Chinese Farmers’ Incomes? A Perspective Based on Total Factor Productivity in Agriculture" Sustainability 17, no. 11: 5034. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115034

APA StyleHuang, B., & Zhu, S. (2025). Does Financial Inclusion Have an Impact on Chinese Farmers’ Incomes? A Perspective Based on Total Factor Productivity in Agriculture. Sustainability, 17(11), 5034. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115034