1. Introduction

The resurgence of global travel underscores the pressing need to prioritize sustainable tourism practices, particularly in light of the increasing economic influence of Generation Z. Experts predict that by 2035 the tourism spending of Chinese Generation Z will reach CNY 16 trillion (approximately USD 2.4 trillion), reflecting their growing impact on the global tourism market. Recent surveys, such as one by HSBC (Q1, 2024), reveal that 62% of travelers in the 18–24 age group are female Gen Z consumers, with 70% making travel bookings less than two weeks in advance [

1].These statistics highlight the significant socioeconomic footprint of Generation Z’s tourism, underscoring the need to guide their behaviors toward sustainability.

Generation Z, born between 1997 and 2012 [

2], is a transformative cohort in both economic and social spheres. While much attention has been placed on their role in China’s digital economy, their influence extends globally. In the U.S., Generation Z is expected to contribute over USD 143 billion to the economy by 2026, with strong preferences for sustainability and digital engagement [

3]. In Europe, the European Commission (2022) reports that Gen Z’s demand for flexible work is reshaping labor markets [

4]. These trends illustrate how this generation’s consumption patterns, including travel, are reshaping economies worldwide. Notably, Generation Z is highly engaged with digital technologies and sustainability. As digital natives, they are not only adept at adopting new technologies but are also increasingly interested in eco-friendly travel options. Studies suggest that this generation is more likely to engage in sustainable tourism [

5] than previous generations, driven by both their values and financial constraints [

6]. Social media and digital platforms play a pivotal role in shaping Gen Z’s travel preferences, as they seek authentic, immersive experiences that align with sustainable practices.

Emotional factors, such as place attachment [

7], satisfaction [

8], and sense experience [

9], have been shown to influence environmentally responsible behavior (ERB) in tourism. Although much research on ERB has focused on physical aspects, such as destination perceptions [

10] and interactions with locals, fewer studies have explored the emotional transformations that occur during travel. With the rise of virtual and augmented reality (VR/AR), tourists can now engage with destinations digitally, fostering deeper connections and promoting sustainable behaviors [

11]. However, most existing studies focus on isolated emotional responses, leaving a gap in understanding how different emotional factors interact to influence ERB [

12]. Theories like the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and the Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) model have explored emotional factors in ERB, highlighting that affective responses such as awe and attachment can drive more sustainable behaviors [

9,

13]. Yet, these models often overlook the role of self-regulation in translating emotions into sustained behavior. The self-regulation of attitude theory, which posits that emotional responses lead to attitude changes and subsequent behaviors, provides a comprehensive framework for understanding ERB over time [

14]. Similarly, the Cognitive-Affective-Conative (CAC) model explains how cognitive, emotional, and conative factors work together to shape behavior [

15]. Despite their promise, these theories have been underexplored in the context of creative tourism [

16].

Creative tourism, which emphasizes participatory cultural experiences, is gaining momentum in China as a strategy to protect intangible cultural heritage and foster sustainable tourism [

17]. This form of tourism, unlike traditional mass tourism, prioritizes authentic, hands-on experiences that engage tourists in the cultural fabric of destinations [

18]. As Generation Z increasingly favors the diversity and authenticity offered by creative tourism, understanding how this form of tourism shapes their ERB is critical for sustainable destination management. Generation Z’s preference for meaningful, off-the-beaten-path destinations reflects their broader values, which prioritize sustainability over material consumption [

19]. Research by Booking.com indicates that Gen Z travelers often choose destinations based on natural beauty and cultural experiences [

19], aligning with their interest in sustainable travel and volunteer tourism [

20]. This makes creative tourism an ideal setting for exploring how emotional engagement with travel experiences can foster ERB. Despite increasing recognition of Generation Z’s influence on tourism, there is a gap in the literature regarding how creative tourism experiences (CTEs) shape their ERB. This study aims to fill this gap by examining the role of emotional engagement in CTE and its potential to drive sustainable behaviors among Gen Z tourists, using the self-regulation of attitude and CAC theories as guiding frameworks.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 provides a comprehensive literature review on creative tourism, tourist engagement, place attachment, and ERB.

Section 3 outlines the methodology, including the research instrument, sampling approach, and data analysis methods.

Section 4 presents the study’s results, including reliability and validity tests, SEM results, and hypothesis testing.

Section 5 discusses the findings, their implications for sustainable tourism management, and the study’s limitations. Finally,

Section 6 concludes with key findings and suggestions for future research.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Theoretical Framework

This study draws on the self-regulation of attitude theory and the cognitive–affective–conative (CAC) framework to develop our theoretical model. Previous research has shown that these theories are effective in explaining the formation of tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior (ERB) [

14,

21]. Specifically, this study examines the role of creative tourism experiences (CTEs) in influencing ERB among Generation Z tourists, with tourist engagement (TE) and place attachment (PAT) serving as mediating factors. The following sections provide a detailed discussion of each component of our theoretical framework.

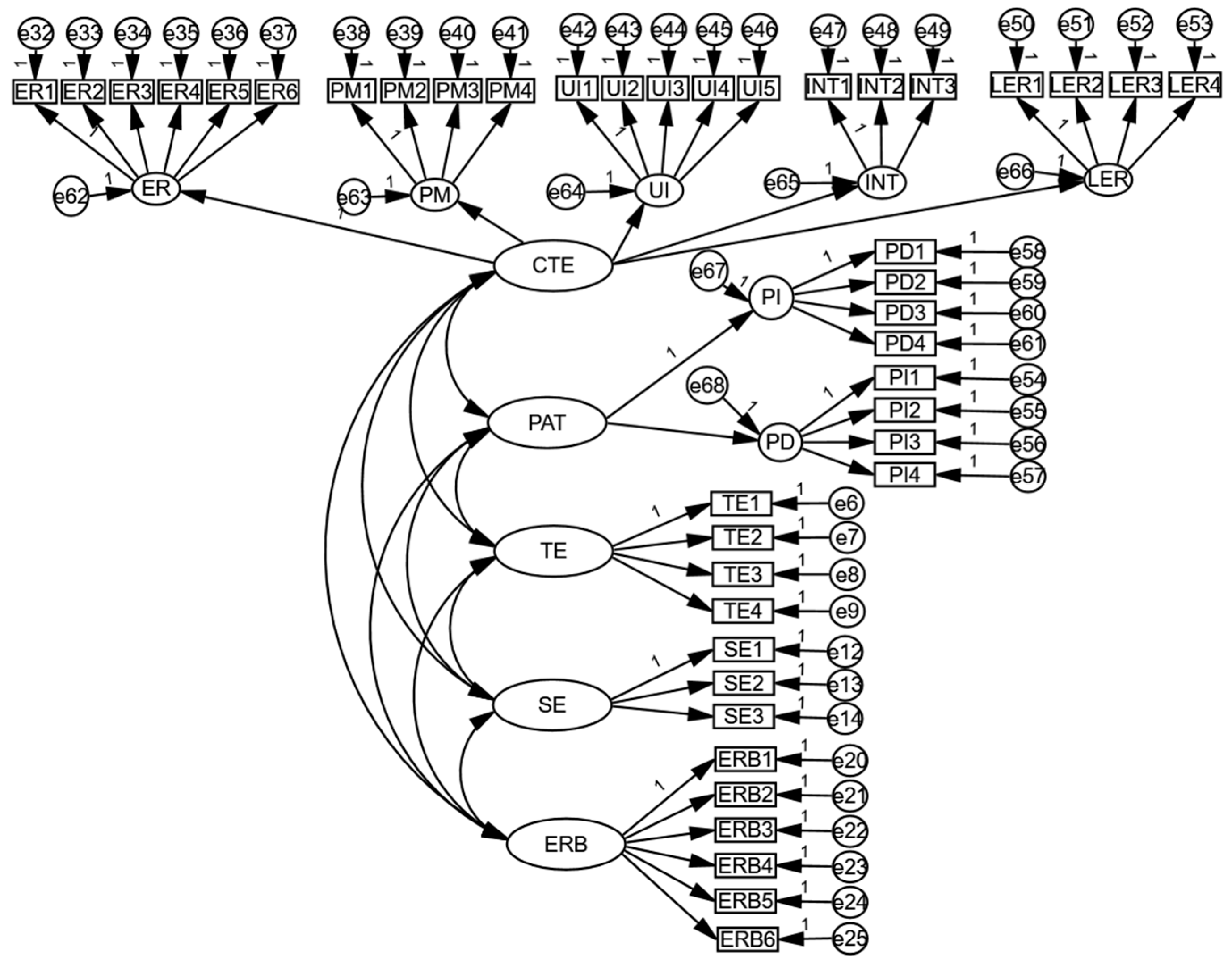

Figure 1 presents the theoretical framework of this study, illustrating the hypothesized relationships between creative tourism experiences (CTEs), tourist engagement (TE), place attachment (PAT), and environmentally responsible behavior (ERB). The framework is based on integration of the self-regulation of attitude theory and the CAC framework, highlighting the mediating roles of TE and PAT in the relationship between CTEs and ERB.

3.1.1. Appraisal Processes: Creative Tourist Experience (CTE)

Creative tourism experiences (CTEs) transcend traditional sightseeing and entertainment by offering participatory, interactive, and personalized activities that immerse tourists in local cultures and creative industries, thus creating unique and memorable experiences [

36]. These experiences are second-order factors encompassing five dimensions, namely, escapism and cognition, inner peace, unique engagement, interaction, and learning [

37], reflecting tourists’ perceptual evaluations of the process of experiencing creative tourism activities.

Generation Z has become a major consumer of China’s recovering tourism industry [

27]. However, there is still ambiguity in the literature regarding the examination of environmentally responsible behavior (ERB) actions within the framework of creative tourism. For instance, Haddouche and Salomone [

38] found that while Gen Z is highly engaged in tourism activities, sustainable tourism is not a key concept for this generation, indicating a gap in understanding their ERB.

This confirms that a positive tourism experience activates tourists’ environmental awareness, stimulates their emotions toward the destination, and encourages them to adopt pro-environmental behaviors [

39]. Similarly, the current CTEs integrated into intangible cultural heritage positively influence tourists’ decision-making, revisiting intentions, and emotions [

40]. Thus, CTEs evoke emotions in individuals and are further considered a strong predictor of tourists’ ERB. Based on these insights, this study suggests the following hypothesis:

H1. CTE contributes positively to ERB.

According to place attachment theory, individuals form emotional bonds with places through positive experiences and interactions [

41]. Creative tourism experiences (CTEs), which are immersive and culturally rich, provide tourists with unique and memorable interactions with a place, thereby enhancing their emotional connection to it [

42]. Studies have shown that engaging in creative and interactive tourism activities leads to stronger place attachment. For instance, research on the impact of creative tourism on place attachment has found that tourists who participate in creative activities report higher levels of emotional bonding with the destination [

43]. As a result, this study developed the following study hypothesis:

H2. CTE contributes positively to PAT.

Engagement theory suggests that interactive and experiential activities increase tourists’ cognitive and emotional involvement [

44]. CTEs, by their nature, provide such interactive experiences, thereby enhancing tourist engagement. Research has demonstrated that creative tourism activities, which often involve learning and social interaction, significantly increase tourists’ engagement levels [

45]. Based on these insights, this study suggests the following hypothesis:

H3. CTE contributes positively to TE.

3.1.2. Emotional Responses: Place Attachment (PAT)

Place attachment (PAT) is an individual’s cognitive or emotional bond with a specific setting or environment [

41]. The person–process–place framework of place attachment highlights that repeated interactions and positive experiences with a place enhance emotional bonds [

46]. Tourist engagement (TE), characterized by active involvement in destination activities, aligns with this framework and is expected to promote PAT. Studies have found that higher levels of tourist engagement lead to stronger place attachment [

47]. For example, research on the impact of tourist engagement on place attachment showed that active involvement in destination activities significantly enhances emotional connections with the place [

48].

H4. TE has a positive influence on PAT.

3.1.3. Activate Affective: Tourist Engagement (TE)

Tourist engagement (TE), derived from customer engagement, is a multidimensional construct encompassing cognitive, emotional, and interactive behavioral activities [

49]. The theory of embodied cognition highlights the importance of aligning contextual and bodily experiences with an individual’s sense of experience. Tourism is an ongoing process, and increased participation in tourism activities can deepen an individual’s exposure and emotional connection to the destination environment, thereby promoting environmentally responsible behavior. Participation theory states that, through active participation in activities, individuals establish a deep connection with the environment and others, thus enhancing their sense of identity with the activity and the environment. In tourism contexts, an increased participation of tourists leads to a deeper understanding of and emotional engagement with the destination environment and increases the quality of relationships, thus translating into ERB [

50]. The results align with the social exchange theory of ERB, which states that tourists interact with destination residents in an exchange that allows for connections to be established through participation in tourism activities and for trust and emotional bonds to be built through the exchange of resources and information. Furthermore, as the exchange deepens, the emotional ties grow, translating into responsible behavior toward the environment [

11]. Therefore, tourist participation can be regarded as an important antecedent of ERB:

H5. TE contributes positively to ERB.

3.1.4. Coping Responses: Mediating Roles of PAT and TE

The TPB suggests that implementing ERB requires the translation of personal intentions into action, a process activated during tourism [

51]. Academics have demonstrated that, while a constant connection between people and their environment enhances the emotional connection to tourism, an increased sense of experience and interactive communication will translate to ERB [

7]. This suggests that the deepening of tourists’ emotions occurs synergistically with continued engagement in tourism activities. Consistent with research examining attitudinal behavioral theory, with regard to individual behavioral transformation, this theory suggests that individuals’ affective attitudes change and that their emotional connection to the destination increases as they engage in destination activities. Thus, the sense of local identification with the destination is further activated and eventually converted into ERB [

52].

The cognitive-affective-conative (CAC) theory posits that cognitive factors (such as CTE) influence affective responses (such as PAT), which, in turn, influence conative behaviors (such as ERB). This suggests that PAT can act as a mediator in the relationship between CTE and ERB [

53]. Studies have shown that place attachment can enhance tourists’ environmentally responsible behaviors by fostering a deeper emotional connection to the destination. For example, research on the mediating role of place attachment found that it significantly influences the relationship between tourism experiences and ERB [

54]. Based on these insights, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H6. PAT plays a mediating role in the connection between CTE and ERB.

The engagement theory suggests that interactive and experiential activities increase tourists’ cognitive and emotional involvement, which can lead to more sustainable behaviors [

55]. This implies that TE can mediate the relationship between CTE and ERB. Research has demonstrated that tourist engagement mediates the relationship between creative tourism experiences and ERB. For instance, a study on the mediating role of tourist engagement found that it significantly influences the relationship between CTE and ERB [

27].

H7. TE plays a mediating role in the connection between CTE and ERB.

The PPP framework of place attachment suggests that active involvement in destination activities (TE) enhances emotional bonds with the place (PAT), which, in turn, promotes ERB [

56]. This implies that PAT can mediate the relationship between TE and ERB. Studies have found that place attachment mediates the relationship between tourist engagement and ERB. For example, Ref. [

57] examining the mediating role of place attachment showed that it significantly influences the relationship between TE and ERB. Thus, this study puts forth the following hypotheses:

H8. PAT mediates the relationship between TE and ERB.

3.1.5. Cognitive Moderation: Self-Efficacy (SE)

Self-efficacy (SE), as defined by social cognitive theory, is a critical determinant of motivation, emotion, and action, referring to a person’s confidence in their abilities to carry out particular behaviors [

58]. Research has confirmed that tourists with a higher SE have more confidence in their abilities, which boosts the interactive experience [

59]. Regarding creative tourism, SE reflects a person’s judgment and confidence in their ability to interact effectively with others [

60]. Current studies have demonstrated the moderating effect of SE, with tourists with a higher SE being better able to integrate themselves into tourism activities, show higher levels of engagement, and overcome obstacles more confidently [

61]. Combined with the current research, an assumption could be made that, in creative tourism, tourists with a higher SE will be more actively involved in the tourism process, and the emotional connection with the destination will increase when the sense of activity experience is enhanced.

Social cognitive theory suggests that individuals with higher self-efficacy (SE) are more likely to engage in activities that lead to positive outcomes, such as forming stronger emotional bonds with a place [

62]. This implies that SE can moderate the relationship between CTE and PAT. Empirical studies have shown that self-efficacy can enhance the impact of tourism experiences on place attachment [

63]. For instance, research on the moderating role of self-efficacy found that it significantly influences the relationship between CTE and PAT. Thus, this study puts forth the following hypotheses:

H9. SE acts as a moderator in the connection between CTE and PAT.

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) posits that self-efficacy influences the likelihood of engaging in specific behaviors [

64]. This implies that SE can moderate the relationship between CTE and TE. Research has demonstrated that higher self-efficacy can enhance tourists’ engagement in creative tourism activities [

65]. For instance, a study on the moderating role of self-efficacy found that it significantly influences the relationship between CTE and TE. Thus, this study puts forth the following hypotheses:

H10. SE acts as a moderator in the connection between CTE and TE.

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) suggests that self-efficacy can influence the likelihood of engaging in pro-environmental behaviors. This implies that SE can moderate the relationship between CTE and ERB [

65]. Empirical studies have shown that higher self-efficacy can enhance the impact of tourism experiences on ERB [

66]. For instance, research on the moderating role of self-efficacy found that it significantly influences the relationship between CTE and ERB. Based on these insights, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H11. SE acts as a moderator in the connection between CTE and ERB.

3.2. Instrument Development and Measures

This research examines the impact of CTE on the ERB of Generation Z tourists, with TE and PAT as mediators, and SE as a moderator. The variables were measured using established scales and a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). CTEs were assessed with a 22-item scale across five sub-dimensions (escapism and cognition, inner peace, unique engagement, interaction, learning) adapted from Ali et al. (2016) [

37]. TE was measured with a 4-item unidimensional scale capturing cognitive, emotional, and behavioral aspects based on Brown et al. (2018) [

67]. PAT was evaluated with an 8-item scale covering emotional and cognitive attachment adapted from Davis et al. (2020) [

68]. ERB was assessed with a 6-item scale focusing on sustainable behaviors. Based on [

69], SE was assessed with a 3-item scale evaluating confidence in sustainable practices, created by White et al. (2021) [

70].

3.3. SEM Causality Analysis Method and Software

In this study, covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) was employed to examine the causal relationships between creative tourism experiences (CTEs), tourist engagement (TE), place attachment (PAT), and environmentally responsible behavior (ERB). CB-SEM is a robust method widely used in tourism research for testing theoretical models and evaluating the relationships between latent variables [

71]. The analysis was conducted using AMOS software (version 24.0), a leading tool for SEM, which allows for the estimation of model parameters, evaluation of model fit, and testing of hypotheses.

SEM was selected for its ability to model complex relationships, including both direct and indirect effects. It is particularly suitable for this study as it can simultaneously test multiple pathways, such as the mediation effects of place attachment and tourist engagement, and the moderation effect of self-efficacy. Unlike simpler methods, such as regression analysis, SEM enables the inclusion of latent variables—such as place attachment and self-efficacy—which are central to this study’s theoretical framework. This capability provides a more comprehensive and accurate model of the relationships between these variables.

To ensure the robustness of the findings, we followed a rigorous process for model specification, estimation, and validation. This process included the assessment of measurement model validity, structural model fit, and hypothesis testing. By utilizing AMOS, we were able to generate detailed output for model diagnostics, which facilitated the interpretation of the direct, indirect, and total effects within the proposed model. This methodological approach provided a clear and reliable examination of how creative tourism experiences influence ERB through tourist engagement and place attachment.

Regression models, while capable of examining direct relationships, would not have been suitable for testing mediated and moderated effects simultaneously. SEM, in contrast, allows for the simultaneous modeling of these effects within a unified framework, capturing the interactions between the processes. Additionally, regression models are not designed to handle latent variables like place attachment or self-efficacy, making SEM a more appropriate choice for this study’s objectives.

3.4. Sample and Data Collection

This study specifically targeted Generation Z tourists by having participants self-select their age group to complete the survey. This approach allowed for a focused analysis of Generation Z’s behaviors, although it limits the ability to compare these behaviors directly with those of other generational cohorts, such as Millennials or Generation X. Future research could address this by incorporating multiple generational groups, providing a broader understanding of generational traits in tourism behavior. Despite this limitation, focusing on Generation Z is valuable, as this cohort, which has grown up in the digital era, is expected to play a significant role in shaping future tourism trends. Understanding their behaviors, particularly in relation to digital engagement, sustainability preferences, and ERB, is increasingly relevant to the tourism industry.

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the survey sample, which includes 639 valid responses. The sample is nearly evenly split by gender (50.55% male, 49.45% female), with the majority of respondents (51.80%) aged between 23 and 27 years. Students represent the largest occupation group (62.74%), which is consistent with the typical participation patterns of Generation Z, particularly among college students and young professionals who have the time and disposable income to engage in tourism activities. The demographic composition of the sample reflects the natural tourism patterns of Generation Z. This age group, especially college students and young professionals, is more likely to participate in tourism activities due to their greater availability of time and income. The sample, therefore, provides a realistic representation of the Generation Z cohort’s tourism participation, and the higher proportion of young adults is an expected outcome of field research in tourist destinations.

The study was conducted from January to March 2024 in Chongqing and Guizhou, two distinct regions in China. Chongqing, a major metropolitan area, offers urban tourism experiences, while Guizhou focuses on eco-tourism and rural development. These regions were selected to capture a diverse range of tourist behaviors across both urban and rural tourism settings. Convenience sampling, a non-probability method, was employed for its practicality and cost-effectiveness, allowing for rapid data collection. However, while this method is common in preliminary research, it may introduce selection bias, limiting the generalizability of the findings to the broader population of Generation Z tourists in China.

Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable insights into Generation Z’s tourism behavior in China. The focus on two regions with distinct tourism offerings allows for an understanding of both urban and eco-tourism behaviors, which reflect broader global trends, including digital engagement and a growing emphasis on sustainable tourism [

72]. Although the study is geographically and temporally limited, the behaviors observed offer useful insights into Generation Z’s tourism preferences and may inform broader trends within this cohort.

Previous studies [

73,

74] have demonstrated that Generation Z exhibits higher levels of digital engagement and a stronger commitment to sustainability compared to older generations. These traits are largely attributed to their upbringing in a digital era where environmental concerns are increasingly prominent. The findings of this study align with these broader generational trends, further highlighting Generation Z’s unique behaviors in tourism contexts.

While the demographic distribution in

Table 1. may appear skewed, it accurately reflects Generation Z’s typical tourism participation patterns, which are strongly influenced by factors such as income and time availability. The sample is therefore not biased, but rather representative of the natural composition of this group. Future research could expand on this by examining how sociodemographic factors like income and education level impact tourism behaviors across a wider range of age groups and populations.

3.5. Methods of Analysis

To ensure the reliability and validity of the data, both exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were conducted. Following this, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test the hypothesized relationships, including direct, mediating, and moderating effects [

75]. Model fit was assessed using indices such as χ

2/df, RMSEA, and SRMR. Structural models were constructed to examine the effects of creative tourism experience (CTE) on tourist satisfaction (TS), place attachment (PAT), and environmentally responsible behavior (ERB), as well as the impact of TS. The mediating roles of TE and PAT were assessed, and the moderating effect of SE on both independent and mediating variables was tested, including the moderated mediation of TE and PAT.

To account for potential confounding influences, sociodemographic variables—such as age, education level, and gender—were included as control variables in the analysis. These factors are known to affect tourism behaviors and environmental responsibility. By incorporating these variables, we were able to isolate the effects of SE and PAT on ERB, ensuring that the observed relationships reflect true associations, independent of demographic differences.

Self-efficacy was treated as a moderating variable in this study. The moderating effect was assessed by incorporating an interaction term (e.g., the product of self-efficacy and creative tourism experience) into the SEM framework. This term allowed us to evaluate how self-efficacy moderates the relationship between CTE and place attachment, specifically examining how the strength of this relationship changes with varying levels of self-efficacy. The SEM model was specified to include this interaction term, and the moderating effect was tested for statistical significance.

It is important to note that this study is based on cross-sectional data, which only allows for the examination of associative relationships between variables at a single point in time. Although we hypothesize that constructs like CTE influence ERB and that engagement leads to attachment, causal claims cannot be made due to the data structure. Future research using longitudinal designs would be needed to establish causal relationships between these variables.

4. Results

4.1. Common Methodological Biases

A factor analysis conducted using SPSS 27.0 identified four factors with eigenvalues above 1, with the first factor explaining 29.19% of the variance—below the 40% threshold—thus meeting Harman’s test criteria. A one-way validated factor analysis further confirmed these results (see

Table 2). The results were as follows: χ

2/df = 2.436 < 3, RMSEA = 0.044 < 0.08, and SRMR = 0.030 < 0.08. All of these results were within their judgment criteria. In addition, most of the other model fit indicators, such as GFI and CFI, reached the criterion of >0.9; thus, the model in this study was found to have a good fit.

4.2. Reliability and Validity Tests

4.2.1. Reliability and KMO Test

Cronbach’s alpha in SPSS 27.0 was used to assess scale reliability, and all coefficients were above 0.7 (

Table 2), thus confirming the questionnaire’s acceptable reliability.

Sample data were analyzed in SPSS 27.0 using the KMO measure and Bartlett’s test.

Table 2 shows that the KMO values exceeded 0.7, and Bartlett’s test yielded

p-values below 0.05, confirming suitability for a factor analysis [

76].

4.2.2. Validity Tests

Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess the internal consistency of the scales, with all coefficients exceeding 0.7, indicating acceptable reliability. Convergent and discriminant validity were assessed using factor loadings, composite reliability, and average variance extracted (AVE). The results confirmed that the scales were both convergently and discriminantly valid.

The study items were adapted from established scales [

77] to ensure content validity. CFA was conducted based on [

78] to assess structural validity, and the model fit indices are shown in

Table 3. The modeling fit was 1 <

= 1.24 < 3, RMSEA = 0.017 < 0.08, and SRMR = 0.024 < 0.08. All remaining fit indices exceeded 0.9, confirming a robust model fit and excellent structural validity of the scales.

In this section, the results are presented of the convergent validity assessment, measuring the correlation between different indicators of the same construct [

79]. Convergent validity was assessed using key indicators, starting with standardized factor loadings (SFLs), which were required to be ≥0.5 [

75]. Composite reliability (CR) was calculated following [

80], with values above 0.6 deemed acceptable. Lastly, the average variance extracted (AVE) was assessed with a minimum threshold of 0.5 [

80].

Table 4 shows the findings.

Table 4 shows that all SFLs exceeded 0.50, with a minimum of 0.729. The lowest CR was 0.8923, well above the 0.7 threshold, and the minimum AVE was 0.6484, surpassing the 0.5 criterion. These findings confirm the scale’s strong convergent validity.

Discriminant validity measures the distinction between constructs. Hair [

75] stated that discriminant validity is present when the square root of a construct’s AVE exceeds its correlations with other constructs. Additionally, Henseler et al. [

81] suggested that Pearson correlation coefficients below 0.9 indicate an adequate discriminant validity.

Table 5 confirms that these criteria are met, thus ensuring good discriminant validity.

4.3. SEM Results

The structural equation modeling (SEM) results, as presented in

Figure 2 and

Table 6, offer valuable insights into the relationships between CTE, TE, PAT, and ERB. The overall model fit indices were excellent:

= 1.28, RMSEA = 0.023, CFI = 1.000, TLI = 1.000, and SRMR= 0.026, indicating that the model explains the relationships between the variables effectively. The model fit was good.

The SEM results, presented in

Figure 2 and

Table 6, provide key insights into the relationships between the variables. Creative tourism experiences (CTE) significantly influence environmentally responsible behavior (ERB) (β = 0.418,

p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1. This finding indicates that participatory cultural activities and immersive environmental education positively encourage sustainable behaviors. The moderate effect size suggests that while the relationship is meaningful, other factors may also contribute to the adoption of sustainable practices among tourists.

To account for potential confounding variables, sociodemographic controls (age, education level, gender) were included in the analysis. The results show that SE and PAT remain significant predictors of ERB, even when these sociodemographic factors are controlled for. This reinforces the robustness of the relationships between CTE and ERB, suggesting that these effects are not driven by demographic differences.

Further supporting Hypothesis 2, CTE also significantly positively affects PAT (β = 0.426, p < 0.001). This result suggests that creative tourism activities strengthen tourists’ emotional connection to the destination. While CTEs are an important factor in fostering place attachment, other influences, such as destination familiarity and past experiences, may also contribute to building this emotional bond.

The positive relationship between CTE and TE (β = 0.389, p < 0.001) confirms Hypothesis 3, highlighting that creative tourism activities enhance tourists’ active participation and involvement. This suggests that CTEs not only increase emotional engagement but also motivate tourists to engage in sustainable behaviors during their visit.

Finally, the significant effects of TE on PAT (β = 0.178, p < 0.001) and ERB (β = 0.301, p < 0.001) support Hypotheses 4 and 5, respectively. These results demonstrate that increased tourist engagement in creative activities fosters stronger place attachment and promotes environmentally responsible behavior. This underscores the crucial mediating role of tourist engagement in the relationship between creative tourism experiences and ERB.

4.4. Mediating and Moderating Effects

4.4.1. Mediating Effects of Place Attachment (PAT) and Tourist Engagement (TE)

Theoretical frameworks in tourism research suggest that CTE can influence ERB through various psychological pathways, including engagement and place attachment. TE reflects active participation in the tourism experience, while place attachment (PAT) represents a deeper emotional connection to the destination. We propose that CTE influences ERB through both these independent mediators, with each playing a unique role in promoting sustainable behavior. Our model tests these separate mediating effects without assuming a strict causal sequence between them. To assess the mediating roles of PAT and TE, we employed structural equation modeling (SEM). Mediating effects were evaluated using the bias-corrected non-parametric percentile bootstrap method, with 5000 resamples, to ensure robust estimations [

82] (see

Table 7).

Table 7 presents the mediation analysis results. The path from CTE→PAT→ERB showed a significant partial mediation effect (β = 0.063,

p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.028, 0.108]), confirming Hypothesis 6. This finding highlights the indirect role of place attachment in promoting environmentally responsible behavior (ERB). Tourists who form stronger emotional bonds with the destination through CTEs are more likely to adopt sustainable behaviors, underscoring the importance of fostering emotional attachment for long-term sustainability.

The CTE→TE→ERB path also demonstrated a significant partial mediation effect (β = 0.117, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.080, 0.163]), supporting Hypothesis 7. Engaged tourists are more likely to exhibit ERB, as their stronger connection to the destination and its sustain-ability goals motivates them to take responsible actions.

Similarly, the TE→PAT→ERB path showed partial mediation (β = 0.010, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.004, 0.022]), confirming Hypothesis 8. This result indicates that active engagement with a destination fosters stronger emotional attachment, which, in turn, promotes ERB. This highlights the crucial role of tourist engagement (TE) in driving environmentally responsible behavior through enhanced place attachment.

In summary, creative tourist experiences (CTEs) are linked to ERB through two dis-tinct mediators: TE and PAT. These findings suggest that both active involvement and emotional bonds contribute to sustainable tourism behaviors. However, it is important to note that the relationships between CTE, TE, PAT, and ERB are associative rather than causal, due to the cross-sectional nature of the data. Further research with longitudinal designs is needed to establish causal pathways.

4.4.2. Moderating Effects of Self-Efficacy (SE)

The results show that the interaction term CTE × SE significantly influenced PAT (β = 0.234, p < 0.001), indicating that SE positively moderates the relationship between CTE and PAT, thus supporting H9. The moderation effect of SE suggests that tourists with higher confidence in their ability to engage in CTEs are more likely to form stronger emotional bonds with the destination. This finding highlights the important role of SE in fostering place attachment and underscores the need to design tourism experiences that empower tourists to feel capable and confident in their participation.

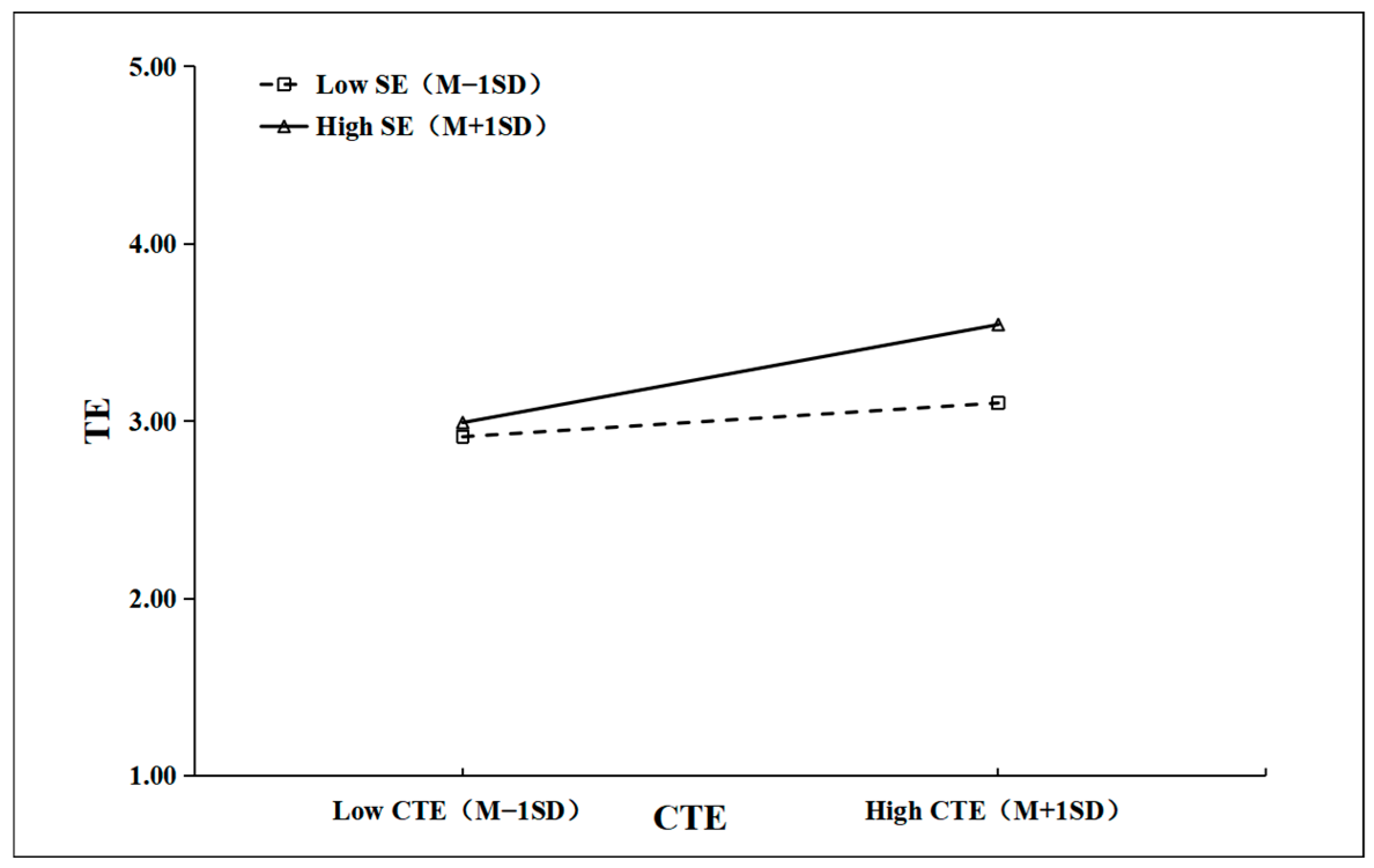

Similarly, CTE × SE significantly affected TE (β = 0.368, p < 0.001), confirming that SE positively moderates the relationship between CTE and TE, thus validating H10. The positive moderation effect of SE on the relationship between CTE and TE suggests that self-confident tourists are more likely to become actively involved in CTEs. This finding emphasizes the role of SE in increasing TE and suggests that tourism managers should focus on enhancing tourists’ confidence to foster deeper participation.

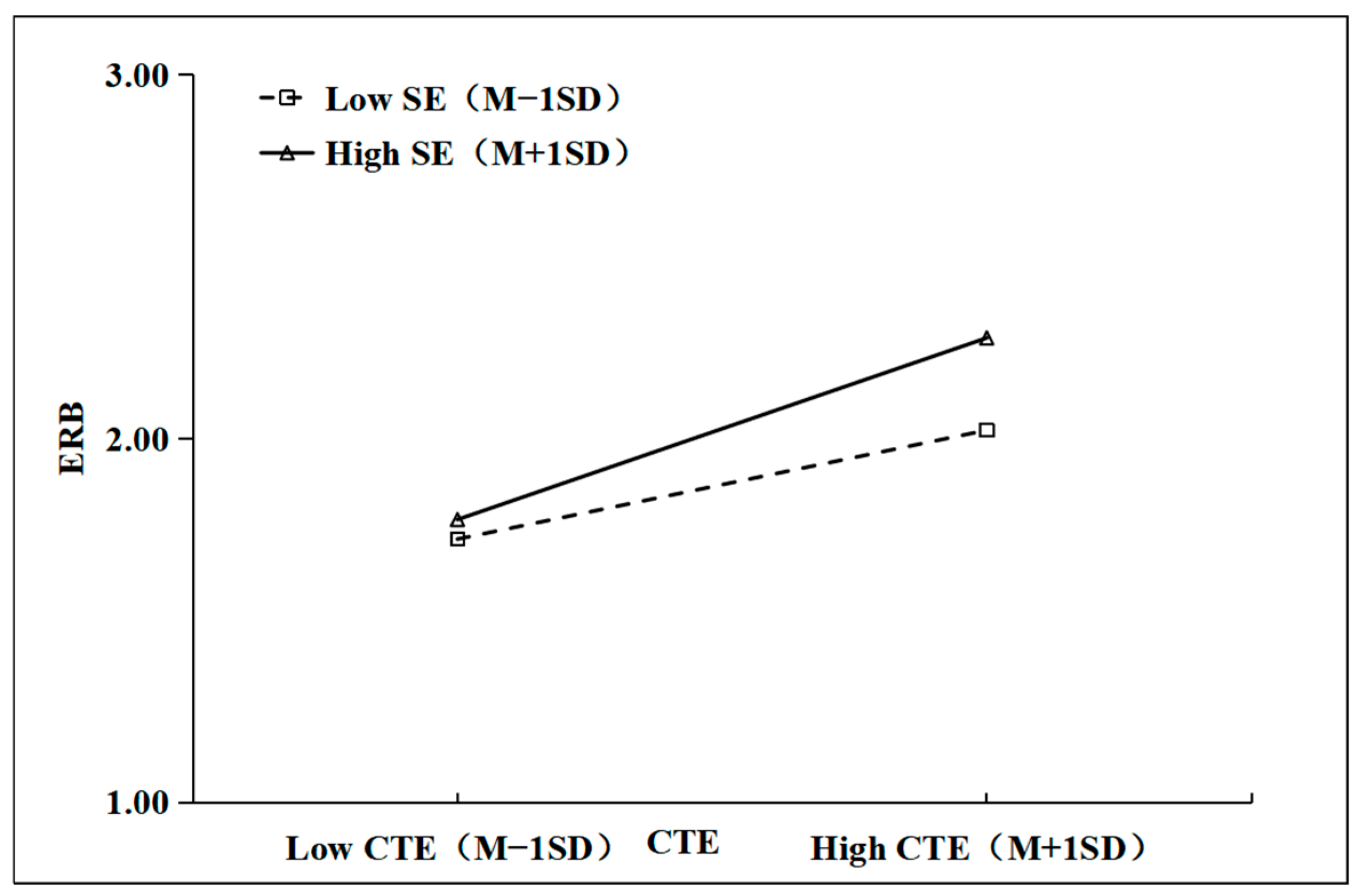

Additionally, CTE × SE significantly influenced ERB (β = 0.208, p < 0.001), demonstrating that SE strengthens the relationship between CTE and ERB, thus supporting H11. The positive moderation effect of SE suggests that tourists who feel confident in their ability to engage with CTEs are more likely to adopt ERB.

To enhance clarity and coherence, in this study, we used the point selection method to categorize SE into three levels: low (M − 1SD), medium (M), and high (M + 1SD). The effects of CTE on PAT, TE, and ERB were analyzed across these SE levels. A simple slope analysis diagram was then generated to illustrate the moderating effects.

Figure 3 shows that the CTE–PAT relationship varies by SE level. The steeper slope indicates that CTE has a stronger effect on PAT when SE is high, while the weaker slope at low SE levels suggests a reduced positive influence.

Figure 4 shows that SE moderates the relationship between CTE and TE. The steeper slope indicates that CTE has a more substantial effect on TE at high SE levels, while the weaker slope at low SE levels suggests a reduced positive influence.

Figure 5 shows that SE moderates the relationship between CTE and ERB. The steeper slope indicates that CTE has a more substantial effect on ERB at high SE levels, while the weaker slope at low SE levels suggests a reduced positive influence

4.4.3. Moderated Mediation Effects

In moderated mediation, one variable acts as a moderator, causing the mediating effect’s strength to fluctuate. This can be tested by integrating the mediation effect into the full model [

83] (see

Table 8). In this study, maximum likelihood estimation with a 95% confidence level was conducted using Mplus 8.0, and the results are shown in the table below.

The CTE→PAT→ERB path remained statistically significant across all SE subgroups, with confidence intervals excluding zero, confirming PAT’s robust mediating role. Additionally, pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences in mediation effects across SE levels, supporting a moderated mediation effect. Specifically, PAT’s mediating effect on the relationship between CTE and ERB increased as SE increased, indicating that SE positively moderates this relationship by amplifying PAT’s role. The moderated mediation effect of TE between CTE and ERB remained statistically significant. The mediating effect of TE increased as SE levels rose, indicating that SE positively moderates the role of TE in the CTE–ERB relationship, and that PAT still had a moderating mediating effect on the relationship between TE and ERB. As SE levels increased, the mediating effect of TE notably rose. In other words, SE moderated the mediating role of TE between PAT and ERB in a positive way.

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of Key Findings

This study explored the relationships between creative tourism experiences (CTEs), tourist engagement (TE), place attachment (PAT), and environmentally responsible behavior (ERB) among Generation Z tourists. The findings provide valuable insights into how immersive and participatory tourism experiences enhance emotional involvement and foster sustainable behaviors. Specifically, CTEs were found to positively influence both PAT and TE, which, in turn, contribute to ERB. Additionally, self-efficacy (SE) was identified as a crucial moderator, suggesting that tourists with higher self-efficacy are more likely to engage in pro-environmental behaviors.

The results also demonstrate that SE and PAT significantly influence ERB, even when controlling for sociodemographic factors such as age, education level, and gender. This underscores the importance of these psychological constructs in shaping environmentally responsible behaviors, independent of demographic influences. Future research should further investigate how sociodemographic characteristics interact with these psychological factors to influence tourism behaviors and sustainability outcomes.

While the study reveals a significant association between CTE and ERB, it is important to note that cross-sectional data cannot establish causality. The findings suggest a relationship between CTE and ERB, but future research should employ longitudinal data to explore the directionality of this relationship. Similarly, an association between TE and PAT was observed, but the study only identifies a correlational link. Future studies should track these constructs over time to establish a clearer understanding of causality between engagement and attachment.

5.2. Discussion of Hypotheses

This study supports Hypothesis 1, demonstrating that creative tourism experiences (CTEs) significantly influence environmentally responsible behavior (ERB) among Generation Z tourists. These findings align with previous research, which suggests that immersive tourism experiences can increase environmental awareness and encourage sustainable practices [

84]. By fostering emotional connections with destinations, CTEs serve as effective tools for promoting ERB, consistent with the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which posits that emotional attachment to places motivates pro-environmental behavior [

85].

Our results also support Hypothesis 2, which posits that CTE positively influences PAT. This aligns with place attachment theory, which asserts that meaningful experiences in a destination can strengthen emotional bonds with that place [

86]. This finding supports place attachment theory, which asserts that meaningful experiences lead to stronger bonds with destinations [

87]. For tourism practitioners, this suggests that incorporating creative tourism can enhance the emotional ties tourists have with a destination, leading to increased loyalty and sustainable behaviors.

In line with Hypothesis 3, the study found that CTE positively affects TE. This supports the engagement theory, which posits that active involvement in tourism experiences fosters stronger connections and more sustainable behaviors [

88]. By encouraging active participation in local culture, CTEs foster a deeper connection between tourists and the destination, increasing their likelihood of engaging in sustainable behaviors. This finding reinforces the importance of engagement in tourism for fostering responsible practices.

Our findings support Hypothesis 4, showing that TE significantly influences PAT. This finding aligns with the person-process-place framework, which emphasizes the importance of repeated interactions and positive experiences in forming emotional connections with a destination [

89]. When tourists are actively involved in destination activities, they are more likely to develop strong emotional ties, which can lead to greater commitment to sustainable tourism practices.

The results support Hypothesis 9, indicating that SE positively moderates the relationship between CTE and PAT. Tourists with higher levels of self-efficacy feel more capable of engaging in meaningful experiences and forming stronger emotional bonds with destinations. This finding aligns with social cognitive theory, which suggests that individuals are more likely to engage in activities that lead to positive outcomes when they feel confident in their abilities [

90].

Hypothesis 10 was supported. This finding highlights the role of self-efficacy in enhancing tourist engagement. Tourists with higher self-efficacy are more likely to actively participate in creative tourism activities, as they feel more confident in their ability to engage in these experiences. This aligns with the TPB, which suggests that self-efficacy influences the likelihood of engaging in specific behaviors.

Hypothesis 11 was supported. This finding underscores the importance of self-efficacy in promoting sustainable behaviors. Tourists with higher self-efficacy are more likely to engage in environmentally responsible behaviors, as they feel more confident in their ability to make a positive impact. This aligns with the TPB, which suggests that self-efficacy influences the likelihood of engaging in pro-environmental behaviors.

The inclusion of sociodemographic control variables (such as age, education, and gender) ensured that the relationships between CTE and ERB were not confounded by demographic factors. The results indicate that self-efficacy and place attachment significantly predict ERB, even when controlling for sociodemographic influences. This reinforces the robustness of the observed relationships.

The use of SEM enabled a nuanced understanding of the relationships between CTE, PAT, TE, and ERB. SEM allowed us to model both direct and indirect pathways, as well as the moderating role of self-efficacy. This provided insights into how self-efficacy influences the mediation between CTE and PAT and ultimately impacts ERB.

While a regression model could have assessed direct effects, it would not have captured the mediated and moderated effects present in the model. Furthermore, SEM allowed us to evaluate the overall model fit, validating the robustness of the hypothesized relationships and ensuring the adequacy of the measurement model.

In summary, Generation Z tourists engage in ERB when emotional involvement and self-efficacy are enhanced through creative tourism activities. These findings underscore the importance of creative tourism in fostering sustainable tourism practices and building resilience among young travelers.

5.3. Theoretical Contributions

This study makes several significant theoretical contributions to the field of sustainable tourism. Firstly, it integrates the self-regulation of attitude theory and the CAC framework to examine the determinants of ERB among Generation Z tourists. This integration provides a comprehensive understanding of the cognitive, affective, and conative processes involved in ERB, filling a gap in the existing literature. Secondly, the study highlights the mediating roles of TE and PAT in the relationship between CTE and ERB. This finding underscores the importance of emotional and cognitive factors in promoting sustainable tourism practices. By demonstrating that TE and PAT mediate the relationship between CTE and ERB, the study provides a nuanced understanding of the mechanisms through which creative tourism can foster sustainable behaviors.

Thirdly, the study investigates the moderating SE on the relationships between CTE, TE, PAT, and ERB. The findings reveal that SE positively moderates these relationships, suggesting that tourists with higher self-efficacy are more likely to engage in sustainable practices. This insight aligns with social cognitive theory and highlights the importance of fostering tourists’ confidence in their ability to make a positive impact on the environment. In summary, this study advances the theoretical understanding of sustainable tourism by integrating multiple frameworks and identifying key factors that influence ERB among Generation Z tourists. The findings provide a foundation for future research and practical interventions aimed at promoting sustainable tourism practices.

In summary, this study shows that Generation Z actively engages in ERB when emotional attachment and self-efficacy are enhanced through creative tourism activities. These findings underscore the potential of creative tourism as an effective tool for promoting sustainable tourism behaviors among young travelers, who are key influencers in shaping the future of global tourism.

6. Conclusions and Limitations

This study explored the role of creative tourism experiences (CTEs) in promoting environmentally responsible behavior (ERB) among Generation Z tourists. The findings reveal the complex relationships between CTE, place attachment (PAT), tourist engagement (TE), and ERB, offering new insights into sustainable tourism. Given Generation Z’s increasing influence as consumers, these findings provide a valuable foundation for destination management strategies aimed at fostering sustainable practices among young travelers.

The use of structural equation modeling (SEM) was essential for examining these complex relationships. SEM allowed for the simultaneous testing of both mediated and moderated effects, providing a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing ERB. Compared to simpler methods like regression analysis, SEM proved more effective in capturing the nuanced dynamics between variables, offering a robust framework for modeling psychological and behavioral interactions in tourism.

The study confirms that creative tourism can be a powerful tool for promoting sustainability, particularly among young travelers shaping the future of global tourism. PAT and TE were identified as key factors influencing ERB, emphasizing the importance of emotional connections and active participation in tourism experiences. Additionally, SE was found to significantly moderate the relationships between CTE, PAT, and TE, highlighting the role of empowerment in increasing engagement and promoting sustainable behaviors. This suggests that tourism management should focus on empowering tourists to foster greater engagement and environmental responsibility.

In summary, creative tourism experiences have significant potential to promote sustainable tourism practices. By enhancing tourist engagement and emotional involvement, and by fostering self-efficacy, tourism destinations can encourage ERB among young travelers. This research provides a framework for destination management to implement strategies that align with the values of Generation Z, offering a roadmap for adapting to the demands of sustainability-conscious travelers.

Future Research

While this study focused on Generation Z tourists in China, future research could extend these findings to global tourism markets. CTEs are adaptable across cultures and geographies and understanding how they influence self-efficacy and ERB in different contexts (e.g., Europe, North America, or Africa) will provide valuable insights for sustainable tourism worldwide. Cross-cultural comparisons could deepen our understanding of how the roles of self-efficacy, tourist engagement, and place attachment vary across different tourism contexts. Longitudinal studies are needed to explore causal relationships and better understand how engagement, attachment, and CTE lead to ERB over time. Data collected at different time points will provide a clearer picture of how these dynamics evolve.

Expanding the geographical scope of future studies by including regions within China and international destinations will help assess Generation Z’s behavior across cultures and seasons. Data collected throughout the year, including during off-peak periods, will offer a more comprehensive view of Generation Z’s tourism preferences. Future research could also include additional activity-related variables, such as entertainment specialization, sense of awe, and tourism support, to broaden the scope of ERB and CTEs. Investigating other moderating factors, like destination responsibility, could provide further insights into the influences on ERB.

Moreover, expanding the generational scope to include cohorts like Millennials and Generation X would help clarify whether the behaviors observed in Generation Z are unique or shared across different generations. This comparison could reveal how sustainability preferences differ or align among various age groups. A significant limitation of this study is the cross-sectional nature of the data, which only allows for associative conclusions. Future research should track participants over time to establish causal pathways, particularly in terms of how engagement and CTE lead to attachment and ERB.

Finally, while self-reported surveys are valuable, they may suffer from social desirability bias, where respondents overstate their commitment to sustainable behaviors. Future studies could include self-consistency measures or self-confidence scores to assess the alignment between attitudes and behaviors. Additionally, dichotomizing key variables, such as sustainability preferences, could help mitigate overreporting and provide clearer insights into Generation Z’s tourism behaviors. By extending this study to other global tourism markets and incorporating longitudinal research, future studies can enhance our understanding of how CTE, self-efficacy, and ERB interact in different contexts, contributing to more effective sustainable tourism strategies worldwide.