Abstract

This research aims to investigate, using the C-A-B theory, the buying decision-making processes of Gen Z consumers in the United States when exposed to fast fashion brand advertising messages including greenwashing elements. Responses of 345 valid participants from the Amazon Mturk platform were analyzed through Mplus 8.11 and SPSS 29. Two-step, structural equation modeling was implemented to test the hypothesis. Additionally, 5000 bootstrapping iterations were used to examine the indirect effects. Study findings indicated that Gen Z consumers responded positively and negatively to fast fashion brands’ product promotional messages. Despite feeling skeptical and betrayed over the greenwashing assertion, they intend to purchase the goods. A contributing factor to this unforeseen purchasing intention may be their indifference towards environmental concerns. Moreover, when greenwashing assertions are infused with product advantages through strategic ingenuity and aligned with the specific demands of certain generations, the perception of positive emotional reaction supersedes the negative, hence facilitating the purchase of the green product. Furthermore, there is evidence of optimism biases, a cognitive bias where they exaggerate their capacity to identify instances of greenwashing, prioritize more on their certain needs, and underestimate the associated environmental risk for others. This clarifies the paradoxical buying patterns of Gen Z consumers. Although Gen Z is the youngest demographic, their tastes for fast fashion apparel may alter as they develop and their lifestyles adapt, influenced by both positive and negative emotional reactions to fast fashion brands. Consequently, the fast fashion business must retain this customer by utilizing sustainability messaging instead of misleading greenwashing assertions in the future.

1. Introduction

The fast fashion industry is considered the second-largest consumer of water and is accountable for approximately 10% of global carbon emissions, which is more than the combined emissions of all international flights and maritime transportation [1]. Specifically, the incineration of textile waste in the fast fashion industry results in the emission of 1.2 billion kilograms of greenhouse gases annually [2]. Additionally, fast fashion consumption’s per capita ecological footprint is 53% higher in developed countries than in developing countries [3]. Although fast fashion poses a substantial environmental threat, it contains inherent characteristics that distinguish it from other business models. For instance, fast fashion is a business model that provides affordable, fashionable apparel through a rapid-response supply chain, which is distinguished by its ability to produce up-to-date merchandise on a bi-weekly basis and its adherence to impermanent trends, as well as its rapid inventory turnovers, mass production, and brief lead times [4]. Upon Zara’s arrival in New York at the commencement of the 1990s, the term “fast fashion” was initially employed. Fast fashion brand service is cost-effective and provides rapid delivery to the consumer with the latest trend, and within a short period [5,6].

Fast fashion brands, known for offering trendy and affordable clothing, remain highly attractive to Generation Z (Gen Z), individuals born between 1997 and 2012 [7], who continue to be a significant consumer base of fast fashion in the United States. These consumers are drawn to garments that are both accessible and cost-effective [8], making them a key target demographic for fast fashion enterprises. As of 2023, Gen Z was the second-largest demographic group in the U.S., with an estimated population of 69.3 million [9]. In response to growing environmental concerns and to appeal to eco-conscious consumers, including Gen Z, many fast fashion brands have adopted promotional strategies labeled as “greenwashing” to divert attention from the industry’s environmental impact [5].

Greenwashing refers to a scenario when there is a discrepancy between what an organization communicates and its performance in fulfilling its environmental responsibilities. The top 10 fast fashion businesses—namely Inditex, Fast Retailing, H&M, Next, C&A, Lojas Renner, Bestseller, Gap, Mango, and ASOS—have engaged in anti-consumerist washing, a form of greenwashing, by failing to adhere to the 2030 agenda of SDG 12 targets as outlined by Garcia-Ortega, Galan-Cubillo, Llorens-Montes, and de-Miguel-Molina [10]. Numerous authors have detailed the practices of “greenwashing” in the context of fast fashion. For instance, H&M, one of the largest fast fashion brands, has been accused of greenwashing because it asserts that it employs organic cotton and recyclable textiles in certain garments. However, its entire business model is predicated on rapid consumption and disposal [11]. The ‘H&M Conscious’ initiative and Zara’s ‘Join Life’ marketing campaign favor a customer pulling strategy rather than remaining sustainable. Both initiatives focus on overconsumption in the name of sustainability [5]. In addition, Zara’s partnership with “Lenzing” (pioneers in the development of Tencel and Modal) to create and utilize sustainable fabrics was perceived as a form of greenwashing, as the environmental consequences of their global operations cannot be alleviated by manufacturing pesticide-free and organic t-shirts [5].

Most current research has focused on the relationships between greenwashing and Gen Z [12], fast fashion and greenwashing [13,14], or fast fashion and Gen Z [15]. One study has investigated the direct and indirect effects of greenwashing on negative green word-of-mouth among Indonesian fast fashion Gen Z customers [16]. Some research also indicated that Gen Z is strongly attached to fast fashion [15]. Nonetheless, they also possess environmental concerns [16,17,18]. However, a significant research gap remains in understanding the paradoxical nature of their consumption behavior. In particular, there is a lack of studies investigating how greenwashing in fast fashion marketing messages influences U.S. Gen Z consumers [19].

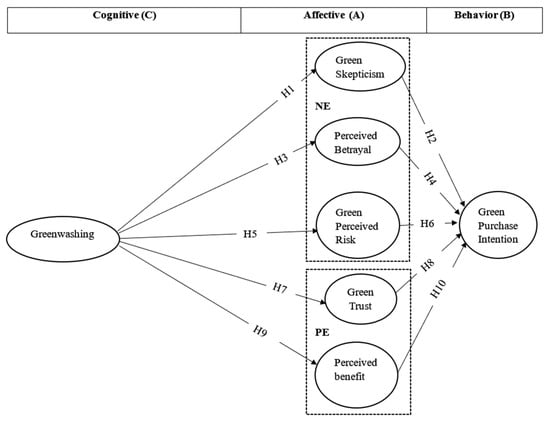

Consequently, this study adopts C-A-B theory to address the identified research gap. Holbrook and Hirschman’s [20] C-A-B paradigm, which incorporates affective elements, encompasses a comprehensive spectrum of relevant emotions, including affection, animosity, apprehension, bliss, ennui, unease, satisfaction, fury, revulsion, sorrow, empathy, desire, euphoria, avarice, remorse, exhilaration, humiliation, and astonishment [19]. The C-A-B paradigm asserts that cognitive (C) is the principal factor influencing emotion (A), which then affects action (B) [21]. This theory has been applied to green consumption studies, as consumers’ emotional reactions to environmental issues and their attitudes significantly influence their willingness to purchase eco-friendly products [22]. However, there has been limited application of the C-A-B framework within the fashion industry. As posited by the theory, emotion serves as the fundamental link in the customer experience [23], and affective components are shaped by emotional responses and individual preferences [24]. Emotional responses to products can be positive (e.g., pleasure) or negative (e.g., anger) and often arise from favorable or unfavorable encounters with the product or service attributes [25]. The psychological dimensional approach classifies human emotions into two fundamental categories: positive and negative. Moreover, products can elicit a wide range of emotions, including both positive and negative reactions [26,27]. In the same context, we assert that fast fashion items provoke both positive and negative emotional responses, depending on the consumer’s behavioral intention and product knowledge [19]. In such a setting, Gen Z consumers may assume that they are less susceptible to the adverse environmental impacts of fast fashion brands, thereby fostering an optimism bias [28].

Consequently, the objective of this inquiry is threefold. It is more thorough and further expands the existing literature and academic work [19]. This research aims to explore the purchasing intentions of U.S. Gen Z consumers toward fast fashion clothes when exposed to promotional activities characterized by greenwashing, using the cognitive–affective–behavioral (C-A-B) conceptual framework. Specifically, it investigates how greenwashing as a cognitive factor influences the green purchasing intentions of U.S. fast fashion consumers via green skepticism, perceived betrayal, green perceived risk, green trust, and perceived benefits [19]. Additionally, the study examines the role of emotion as a critical affective link shaping Gen Z consumers’ overall experience and behavioral response in the context of fast fashion consumption. Further, the study explores the characteristics of promotional activities in fast fashion brands influencing consumer purchase intentions. This study represents the first effort to investigate greenwashing practices among fast fashion firms through the lens of the C-A-B theory. It aims to advance the greenwashing literature by examining the contradictory purchase patterns of Gen Z fashion customers. By highlighting the critical roles of cognitive and emotional factors in shaping responses to greenwashing messages, this research provides both theoretical and practical insights into the complexities of Gen Z’s engagement with fast fashion.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Fast Fashion Brand, Greenwashing, and US Gen Z Consumers

Bick et al. [29] characterized fast fashion as ‘easily accessible, affordably produced contemporary apparel’. Munir and Mohan [5] assert that the fast fashion business model relies on the principle of ‘fashion obsolescence’, whereby firms propagate a ‘throwaway’ culture that undermines any pro-environmental efforts. This business model conflicts with an objective established by the European Commission, as outlined in the European Green Pact, which asserts that by 2030, clothing must be ‘more durable, repairable, reusable, and recyclable’ to address fast fashion, textile waste, and the destruction of unsold textile products. Deflecting attention from policymakers and attracting environmentally conscious consumers, in recent years, numerous fast fashion companies have initiated sustainable communication campaigns focused on fundamental assertions such as ‘utilizing organic cotton’, ‘reusing or second-hand’ (e.g., Zara Pre-Owned), and establishing eco-friendly sub-brands (such as Zara’s Join Life or H&M’s Conscious) to demonstrate their commitment to sustainability and environmental stewardship [30]. Notwithstanding these efforts, some customers continue to be skeptical and suspicious of the marketing communications used by fast fashion firms. Between 2019 and 2022, the frequency of greenwashing-related news articles in conventional media and social networks, particularly on Twitter and LinkedIn, has doubled annually, with the fashion sector being one of the most examined by consumers [31].

The fashion consumer’s suspicion is justifiable. For instance, although sustainability issues are increasingly included in the marketing strategies of fast fashion firms, consumers continue to be doubtful and wary of the vague and sometimes deceptive sustainable brand messaging. Research findings indicate that customers recognize greenwashing in the messaging of all fast fashion firms. The notion of greenwashing intensifies when fast fashion businesses engage in advertising campaigns [30]. For instance, Zara’s ‘Join Life’ marketing tagline encourages customers to “bring the clothes you no longer want and deposit them in the containers located in the stores”. Initially, this tactic attracted shoppers to its stores and then highlighted the disposability of clothing [32]. The H&M Conscious project has been seen as a public relations maneuver to attract environmentally conscious shoppers. H&M has promoted the disposal of second-hand clothing in its stores as an environmentally responsible business practice; however, this initiative has faced criticism as a tactic to entice customers to increase their spending through the offer of discount vouchers [33]. According to the Guardian, H&M’s assertion of collecting 1000 tons of worn clothing is only a kind of greenwashing, given they manufacture the same volume in merely two days [34]. Fast fashion companies have implemented green initiative claims by addressing minor aspects of sustainability [35]. For instance, the Norwegian Consumer Authority accused H&M of greenwashing, asserting that promoting information as sustainability supplied by the company was ambiguous, inadequate, and deceptive. It has made the error of ambiguity by promoting its products as sustainable without offering any specific details [36]. H&M claimed that 1000 tons of worn clothes cannot be entirely recycled due to the variations in textile mixes present in each garment. This technology is not available in the market; hence, H&M should have maintained transparency in their marketing communications and avoided misleading consumers [33]. There was also evidence of hidden trade-off in the name of sustainability of fast fashion brands. For instance, the supply chains of fast fashion businesses are dubious as they obtain materials from poor and middle-income countries [6] that lack environmental resources and disregard environmental concerns [29]. To satisfy the specified timeframe for delivering products to consumers, they rely on air transportation, which is accountable for releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. In addition, merchants such as Zara, Gap, and H&M burn their garments due to erroneous assumptions, contributing to environmental pollution [6].

In the United States, fast fashion brands possess a massive market for Gen Z. Forever 21 emerged as the most favored apparel brand among Gen Z, with more than fifty percent of respondents expressing their preference for the brand. H&M secured the second position, closely trailing behind [37]. Another fast fashion brand, Shein’s share of the fast fashion market in the United States more than doubled from March 2020 to 2022, securing the greatest market component [38]. Even though Gen Z in the U.S. intended to purchase ethically, the most favored brands are predominantly ecologically harmful fast fashion corporations [37].

The preceding discussion and research findings indicate that consumers are increasingly aware of greenwashing, and certain attitudes and behaviors may help explain how the fast fashion industry continues to thrive despite its environmental harm [30]. As the youngest consumer segment, Gen Z’s strong affinity for fast fashion businesses, despite the growing environmental concerns, warrants further investigation. If this consumption pattern persists, it will result in significant environmental repercussions. This study focuses on elucidating the paradoxical consuming behavior of U.S. Gen Z from a theoretical standpoint, with particular emphasis on the psychological components that shape their decision-making.

2.2. The Cognition–Affect–Behavior Theory

The cognition–affect–behavior (CAB) paradigm has been extensively utilized in studies on consumer-based emotions [39,40]. The cognitive element pertains to the cultivation of customers’ values, attitudes, and thoughts around an item [41]. The affective element refers to the emotions and attitudes that customers have toward a certain object [41,42]. The behavior element pertains to the formation of one’s purpose and subsequent conduct toward an object [42,43]. Havlena and Holbrook [44] argue that emotion plays a crucial role in the consumption experience. The usage of a product triggers these feelings and has an impact on various phases of the consumption process [23]. Consumers’ favorable consumption feelings lead to increased future service usage and ultimately influence their inclination to promote the product or service [45].

The psychological dimensional method commonly categorizes emotions into two aspects: positive and negative [46]. Products may elicit a diverse array of emotions, including both positive and negative responses [26,27]. In the same context, we contend that fast fashion items elicit both positive and negative affective responses, contingent upon the consumer’s behavioral intention and product knowledge. For instance, greenwashing happens through verbal and nonverbal cues. Verbal cues can involve deceptive claims and strategies, whereas nonverbal cues include nature-evoking elements, also termed as executional greenwashing [47]. Therefore, when a consumer is able to detect greenwashing from a fashion brand, it creates negative emotions such as perceived betrayal [13], green skepticism [16], and green perceived risk [14]. However, the inability to detect greenwashing phenomena may create green trust [48] and the perceived benefit of the product or services [49]. From the previously published research findings, it has been seen that those affective elements impact consumer behavioral intention. Furthermore, Nguyen et al. [50] mentioned that consumers’ cognitive awareness was being altered because of the increasing prevalence of greenwashing practices. The C-A-B theory encapsulates the direct impact of cognition on affective reactions, which in turn influence collective behavior, thereby motivating an individual to engage in specific behaviors [51]. Therefore, this study exposes fast fashion brand promotional activities and focuses on how Gen Z consumers in the U.S. make purchasing decisions.

2.3. Hypotheses Development

2.3.1. Greenwashing and Green Skepticism

Skepticism generally refers to an individual’s inclination to doubt, distrust, and question [52,53]. Consumers are aware of greenwashing, which causes them to doubt the authenticity of companies’ environmentally friendly efforts [48,54]. Greenwashing engenders distrust towards environmentally friendly assertions [48,55]. Furthermore, previous research findings have indicated that greenwashing has a substantial positive impact on green skepticism [16,50,56].

Consumers who are doubtful of a company that exploits environmental trends for their benefit develop unfavorable opinions of the company’s brand and are less likely to buy its items [57,58]. Consumers may become skeptical when they see inconsistent green marketing and company behavior [59]. Due to consumer skepticism regarding green claims, they may choose to discontinue purchasing the green product [50,60]. Therefore, for fast fashion Gen Z consumers in the United States, the following hypothesis is put forth (Figure 1):

H1.

Greenwashing has a positive impact on green skepticism.

H2.

Green skepticism has a negative impact on green purchase intention.

Figure 1.

Research conceptual model (PE = Positive Emotions, NE = Negative Emotions).

2.3.2. Greenwashing and Perceived Betrayal

Perceived betrayal is a metric employed in the marketing industry to gauge the degree to which consumers perceive purposeful violations of interaction rules by a corporation [61]. As the level of consumers’ perception of corporate greenwashing increases, their negative feelings become more intense, ultimately resulting in a stronger feeling of betrayal [13,62].

Consumers’ environmentally friendly beliefs influence their environmentally conscious purchasing behavior [63]. Consumers who have received favorable communications from corporations demonstrate a substantial decline in their behavior when they discover that these companies are engaged in or endorse unfavorable socially responsible actions [64]. Exposed to a greenwashing claim, when consumers feel betrayed, they show a negative tendency to buy the product [13]. This perceived betrayal leads to a decreased propensity to purchase from the company. Consequently, for Gen Z consumers of fast fashion in the United States, we establish the following hypothesis:

H3.

Greenwashing has a positive impact on perceived betrayal.

H4.

Perceived betrayal has a negative impact on green purchase intention.

2.3.3. Greenwashing and Green Perceived Risk

According to Chen and Chang [65], green perceived risk refers to the anticipation of unfavorable environmental repercussions linked to purchasing behavior. They observe that it is an anticipation of adverse consequences linked to environmental results. Deceptive green advertising can encourage consumers to perceive a higher level of danger connected with the items they consume. As a result, greenwashing claims with deceptive strategies are positively linked with green perceived risk [48,56]. Lu et al.’s [14] research on fast fashion consumers showed that greenwashing was positively impacted by green perceived risk. Perceived risk is associated with the potential outcomes of an incorrect decision [66].

Consumers’ assessment and trust in a product’s true worth before making a purchase is influenced by information asymmetry, which in turn impacts their inclination to buy. This scenario enables the vendor to behave opportunistically [67]. Consumers’ likelihood of purchasing a product decreases when they perceive a significant level of risk associated with it [14,68]. Hence, for American Gen Z customers of fast fashion, we put forward the subsequent hypothesis:

H5.

Greenwashing has a positive impact on green perceived risk.

H6.

Green perceived risk has a negative impact on green purchase intention.

2.3.4. Greenwashing and Green Trust

Without confidence in the company’s green claims, consumers are unable to assess their green purchases [48]. Greenwash poses a challenge to green marketing, making it challenging for customers to discern the effectiveness of green activities [54]. Consumers have become aware that several corporations often deceive them and fail to fulfill their environmental obligations and that greenwashing negatively impacts green trust [48].

The characteristics of environmentally conscious consumers, as identified by Akturan [69], include factors such as price, promotion, relevance, perceived quality, trust, and environmental concerns. These factors, as discussed by Hopkins and Roche [70], Kim and Choi [71], Tarabieh [72], Zaidi et al. [73], and Weisstein et al. [74], have a significant impact on consumer intentions to purchase green products. This research assumes that green trust is a significant indicator of green purchase intention. Therefore, we put forward the below hypothesis for fast fashion Gen Z consumers in the United States:

H7.

Greenwashing has a negative impact on green trust.

H8.

Green trust has a positive impact on green purchase intention.

2.3.5. Greenwashing and Perceived Benefit

Consumers not only want contentment with the product’s performance but also desire additional advantageous outcomes [75]. Babin et al. [76] mentioned that when individuals recognize the advantages of green products, their attitudes and opinions tend to become favorable. However, greenwashing, which lacks further benefits, would be seen negatively.

Consumers’ purchasing intention is influenced by their expectations of the consuming experience [77]. When a claim of greenwashing does not offer a prospective advantage of a product, it is then negatively associated with the perceived benefit, which refers to the consumption of the green product [49]. The study conducted by Dong et al. [78] found a favorable correlation between the perceived benefit of the product and the desire to make environmentally friendly purchases. Therefore, for Gen Z consumers of fast fashion in the United States, we have the following hypotheses:

H9.

Greenwashing has a negative impact on perceived benefits.

H10.

Perceived benefits have a positive impact on green purchase intention.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Participants and Study Procedure

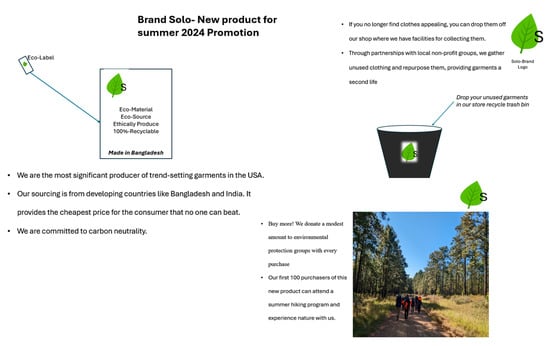

An online survey through Qualtrics was conducted to investigate the predicted hypothesized relationships. The study targeted consumers in the United States between the ages of 18 and 26 and collected data through Amazon Mturk. To give participants a better understanding of the survey topic, an introduction was provided in which they were informed that fast fashion clothing brands are presently advertised as environmentally friendly. To counteract the influence of the halo effect associated with well-known brands, a hypothetical fast fashion brand called “Solo” was employed. Demographic information was first collected. Then, participants were exposed to a group of promotional messages with images from the brand name “Solo”. To offer a visual representation of the fast fashion brand’s promotional procedure, a hypothetical scenario with promotional messages was developed in each image.

The promotional message (Figure 2) was imbued with greenwashing features proven through existing literature. For instance, trend-setting garments draw consumers to consumption and throwaway culture which is against the sustainability concept [6]. Developing countries frequently engage in greenwashing activities, as they contribute to environmental degradation through the production of clothing. There were no rigorous regulations or standards regarding environmental regulations and labor rights [29]. Even though fast fashion brands promote carbon neutrality, to satisfy the specified timeframe for delivering products to consumers, they rely on air transportation, which is accountable for releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere [6,79]. Furthermore, we developed a product label that included the terms “Eco-Material”, Eco-Source”, “Ethically Produce”, and “100%-Recyclable”. “Eco” is one of the most frequently employed lexicons by fashion brands to demonstrate their commitment to environmental sustainability, and it is misleading [80]. The term ethically produce is also one eco-label that fast brands use most often [5]. The term “100% recyclable” was mentioned as a greenwashing term, as it is impossible to transform an entire material into a new product. Figure 2 presents the promotional messages.

Figure 2.

Fast fashion brand “Solo” promotional message.

Furthermore, promotional messages were infused with greenwashing characteristics. For instance, collecting unused clothing was a replication of the H&M conscious initiative, which was referred to as a “greenwashing” phenomenon. It was the process of returning apparel to the manufacturer if consumers no longer found it alluring. In that initiative, fast fashion brands generated substantially more than mere collections [5]. Promotional messages also focus on the collection of unused clothes. For example, each purchase can donate small sums to environmental protection organizations. The sole purpose was to sell more, and it is an example of greenwashing [81]. Then, it was stated that the first one hundred individuals were allowed to go hiking, as Gen Z is the youngest generation, and adventurous activities match their personality. Messages introduced executional greenwashing by capturing images of nature while hiking during the summer [47].

All these promotional messages were characterized by greenwashing phenomena, which involved misleading messages to promote potential products and environmental benefits, which have been used by fast fashion brands most often. Participants must dedicate a minimum of 30 s to those promotional messages. Afterward, the participants filled out a six-point Likert scale questionnaire ranging from strongly disagree (1) to 6 strongly agree (6), which measured their general perception of greenwashing by fast fashion brands. After data cleaning (removing participants having an incomplete response in question and failed attention-checking questions and manipulations), 345 of 371 valid responses were generated for data analysis. Table 1 represents the sample characteristics with frequency and percentage.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (n = 345).

In our sample, the number of male participants exceeds that of female participants. However, previous research suggests that gender imbalance does not pose a threat to internal validity unless it systematically interacts with the study variables [82,83]. In this study, gender is neither a moderator nor the central variable of any proposed hypothesis. Furthermore, the sample reflects a specific timeframe and consists of U.S. Gen Z consumers who expressed interest in greenwashing-related research via the Amazon MTurk platform. We opted not to apply a quota sampling system due to the absence of reliable data on the exact gender distribution of Gen Z consumers in the U.S. In addition, quota sampling can introduce selection biases and non-probability sampling errors, especially when targeting a 50/50 gender split. Furthermore, a high proportion of male participants of Gen Z in the U.S.A. was observed through Wojdyla and Chi’s [15] research on fast fashion. Rather than a limitation, the author mentioned it as a compelling avenue for future research. Our survey’s significant proportion of male participants among Gen Z consumers further substantiates this.

3.2. Measurement

The study employed established and validated measurement scales from prior literature to ensure the reliability and validity of the constructs. Greenwashing was evaluated using a 5-item scale adapted from [65], capturing consumer perceptions of misleading environmental claims made by companies. Green purchase intention was measured using a 4-item scale from [14], which reflects consumers’ willingness to engage in environmentally friendly purchasing behavior. A 4-item scale developed by [50] was used to assess green skepticism, reflecting consumers’ doubt or disbelief regarding the authenticity of green marketing claims. Green trust, indicating the level of consumer confidence in the environmental commitments of companies, was measured using a 5-item scale from [84]. Perceived green risk, referring to the potential negative outcomes associated with green product purchases, was captured using a 4-item scale from [65]. Perceived benefit, encompassing the advantages consumers associate with green products, was measured through a 6-item scale adopted from [49]. Lastly, perceived betrayal—reflecting feelings of being misled or deceived by companies claiming to be environmentally responsible—was assessed using a 4-item scale from [13].

To examine potential multicollinearity and inter-item correlation, SPSS version 29 was utilized. The results showed that all Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values were below the commonly accepted threshold of 5, and tolerance values exceeded 0.10, confirming the absence of multicollinearity issues among the constructs [85]. A comprehensive list of the measurement items is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Items description and factor loading.

4. Results

The findings of the one-sample t-test performed in SPSS indicate that our manipulation of greenwashing [65], as an independent variable, was effective. The test result was deemed 3, since it signified the midway point on the six-point Likert scale. Scores over 3 showed that respondents saw the brand name “Solo” as engaging in greenwashing business practices at a significance level of p < 0.01. However, effective manipulations inflate bias as participants give their response based on certain phenomena in the overall survey [86]. Such a scenario occurs in our survey. Harman’s one-factor test was performed to evaluate the existence of common method bias. This statistical study seeks to ascertain if a single underlying factor may explain a substantial amount of the variation in the observed variables. The findings reveal that the one-factor solution accounted for just 53.65% of the total variation, a little bit above the widely recognized criterion of 50% [87]. However, Harman’s single factor test has some limitations, including false negatives and low sensitivity in the complex model [88]. So, we have done common latent factor (CLF) in CFA through Mplus software. Comparing the CLF model with the baseline model (without CLF), the difference in CFI value is 0.014, which is below the threshold for common method bias concern >0.02, as the model fit did not significantly improve [82,89,90]. In addition, theory should not be compromised to address research inquiries, and a complicated model under constrained experimental conditions may need less stringent criteria [85,91].

The analysis of data was performed using a two-step structural equation modeling (SEM) methodology with Mplus 8.11. A confirmatory factor analysis was first used to evaluate the measurement model. Cronbach’s alpha exceeded 0.70 for all variables (Table 2), so satisfying the acceptable threshold. Table 3 demonstrates reasonable relationships among all constructs. In terms of convergent validity, the average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR) for each variable exceeded 0.5 and 0.7, respectively, thereby satisfying the acceptance criteria [84]. χ2(df = 443) = 1016.808, p < 0.0001, χ2/df = 2.29, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.03, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93 are the fit indices that indicate a satisfactory fit of the measurement model. The fit indices demonstrated values that complied with the rigorous conventional standards and were frequently recommended as effective cutoff values [85,91].

Table 3.

Correlations of all constructs.

Next, the results of the SEM analysis indicated that the model fit was nearly acceptable (χ2(df = 454) = 1403.280, p < 0.0001, χ2/df = 3.0; RMSEA = 0.08; CFI = 0.90; TLI = 0.89; SRMR = 0.06). The SEM analysis for the indirect path effect was conducted through 5000 bootstrapping. Hair et al. [91] asserted that the theory being tested should never be compromised by the desire to attain an excellent fit. As a result, CFI and TLI values are a little bit less than the traditional accepted cut-off criteria. Hair et al. [91] also mentioned that “more complex models with smaller samples may require somewhat less strict criteria for evaluation with the multiple fit indices” (p. 642). Furthermore, goodness-of-fit assessments are significantly influenced by model complexity, and general rules of thumb being more significant than 0.9 may be misleading due to their lack of consideration for contingencies [92].

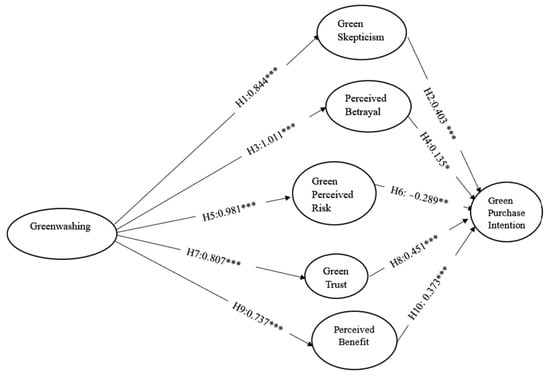

4.1. Direct Path Effect

According to the statistics, greenwashing phenomena have a substantial effect on green skepticism (β = 0.844, p < 0.001), perceived betrayal (β = 1.011, p < 0.001), green perceived risk (β = 0.981, p < 0.001), green trust (β = 0.807, p < 0.001), and perceived benefit (β = 0.737, p < 0.001). The perception of greenwashing is positively correlated with Gen Z’s feelings of green skepticism, perceived betrayal, perceived risk, perceived benefit, and green trust. Therefore, hypotheses H1, H3, and H5 were accepted. Hypotheses H7 and H9 were rejected. The unstandardized regression weight between greenwashing perception and perceived betrayal was the strongest among all latent variables in the full model (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Latent model showing structural unstandardized path coefficient. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

The findings revealed that green purchase intention was significantly and positively associated with green skepticism (β = 0.403, p < 0.001), perceived betrayal (β = 0.135, p < 0.05), green trust (β = 0.451, p < 0.001), and perceived benefit (β = 0.373, p < 0.001), while it was negatively influenced by green perceived risk (β = −0.289, p < 0.01). Therefore, hypotheses H6, H8, and H10 were accepted. Hypotheses H2 and H4 were rejected. The unstandardized regression weight between green trust and green purchase intention was the strongest in that path (Table 4).

Table 4.

Direct path effect hypothesis result.

4.2. Indirect Path Effect

This research investigated the activation of the indirect impact of greenwashing on green purchasing intentions via a mediating variable (green skepticism, felt betrayal, green perceived risk, green trust, perceived advantage). We used the bootstrap confidence interval approach, with 5000 iterations to assess the indirect impact. Table 5 indicates that the bootstrap test showed that all the unstandardized coefficients of the mediating variables satisfied the 95% confidence interval thresholds for both lower and upper limits. Therefore, the indirect effect of greenwashing on the desire to purchase “Solo” brand products was influenced by positive and negative affective elements.

Table 5.

Indirect path effect hypothesis result.

5. Discussion

This study aims to investigate the purchasing behaviors of Gen Z consumers in the United States when they are exposed to fast fashion promotional activities that incorporate greenwashing elements. The study results indicate that greenwashing positively impacts green skepticism. This means that Gen Z consumers doubted, disbelieved, and questioned the environmental promotion of the “The Solo” brand. This discovery aligns with studies indicating that consumers may develop skepticism when observing discrepancies between green marketing and corporate conduct [16,50,56]. The latent variables contain emotions, and the greatest unstandardized regression weight is found between the perception of greenwashing and perceived betrayal. Exposed to the greenwashing promotional message from the “Solo” brand, Gen Z consumers show strong negative feelings, which result in perceived betrayal. Perceived betrayal refers to marketing to assess the extent to which customers recognize intentional breaches of interaction norms by a firm [61]. This also aligns with the findings that as consumers’ awareness of corporate greenwashing escalates, their unfavorable sentiments intensify, culminating in a heightened sense of betrayal [13,62,93]. As expected, greenwashing positively influences green perceived risk. This means that the expectation of adverse ecological consequences is associated with “Solo” brand marketing promotion. This is in line with the previous research findings that the rise of greenwashing practices may induce customer doubt regarding the environmental performance of organizations [14,48,56].

Contrary to the hypothesis and previous research findings [48], study findings indicate that greenwashing has a positive influence on green trust. Gen Z has a favorable attitude toward the deceptive environmental claims of fast fashion businesses. Greenwashing presents a significant obstacle to green marketing, complicating customers’ ability to evaluate the efficacy of environmentally friendly initiatives [54]. In our case, the environmental benefits, claims, and initiatives mentioned in the “Solo” brand promotional activities create a willingness in Gen Z consumers to believe in the brand’s environmental credibility. Part of this phenomenon also originated from optimism biases, a sort of cognitive bias. Weinstein [28] noted that optimism bias, a cognitive distortion, develops when people see their actions as secure due to their ingrained ideals, regardless of the possible negative repercussions for others. Gen Z views “Solo” as a company that contributes to environmental organizations, emphasizes recyclability, and promotes carbon neutrality, while still addressing their requirements for hiking options and affordable, fashionable apparel. They did not rigorously assess the examination of such allegations. They overrate their capacity to identify greenwashing occurrences and undervalue the related risks, opting to accept some aspects of the assertion. Consequently, green trust was established via cognitive biases. Furthermore, the significant association of positive greenwashing perception with product-perceived benefit was contrary to the hypothesis and previous research findings of Braga et al. [49]. Perceived benefit refers to consumers’ wanting not only pleasure from a product’s performance but also further advantageous benefits [75]. Furthermore, when the advantages of green products are recognized, an individual’s attitudes and beliefs will shift positively, but greenwashing will be seen negatively due to its lack of further benefits [49]. In this research, the “Solo” brand products are not limited to environmental benefits but also offer additional perqs such as the cheapest newly trended product and hiking opportunities. Thus, even promotion imbued with greenwashing phenomena has a positive correlation with perceived benefit.

In opposition to the hypothesis and prior study results [50,60], green skepticism positively impacts green purchase intention. Furthermore, perceived betrayal is positively linked with buying intention for the “solo” brand, which was against the research findings of Sun and Shi [13]. The explanation can be given that even though the “Solo” brand promotional messages were imbued with greenwashing phenomena, Gen Z posed a lack of concern regarding the environment and chose to buy the product. In comparison to all other affective element responses to green purchase intention, the positive weighted unstandardized coefficient between green trust and green purchase intention was the highest. A probable explanation is that even though all “Solo” brand messages are imbued with greenwashing phenomena, they found some of the messages to be trustworthy and provided some positive attributes regarding environmental claims and perceived benefits based on their needs, which led them to buy the “Solo” brand product. In addition, this phenomenon can also be further extended through the lens of optimism bias, a sort of cognitive bias mentioned by Weinstein [28] and C-A-B theory [23]. In this research, greenwashing as a cognitive element refers to the development of consumers’ values, attitudes, and perceptions of a product [20,23]. Previous research indicated that consumers’ cognitive awareness was being modified due to the rising frequency of greenwashing tactics [50]. This situation is evident in our research findings. Gen Z evaluates greenwashing charges peripherally for the “Solo” brand, driven by their desire for inexpensive apparel and recreational activities such as hiking. They overestimate their ability to recognize instances of greenwashing and underestimate the associated hazards for others, choosing to accept/trust some elements of the claim. This resulted in optimism biases, where positive emotional responses surpassed negative ones, hence enhancing their inclination to acquire fast fashion items. Furthermore, the significant association of green purchase intention with product-perceived benefit is in line with the hypothesis and previous research findings of Dong et al. [78]. As the “Solo” brand promotion contains product benefits, including trendy products with affordable prices and the first one hundred purchasers receiving hiking opportunities, they observe and believe product benefits aside from environmentally friendly claims. They find it opportunistic to buy the product. As expected, a significant negative correlation existed between green perceived risk and green purchase intention. The result of the study matches the findings of Lu et al. [14]. This means that when Gen Z perceived the possibility of concern about the product’s green performance and image, they tended to avoid purchasing the product. This aligns with the finding that the likelihood of purchasing a product decreases when consumers perceive a substantial level of risk associated with it [68]. U.S. Gen Z consumers demonstrated a combination of positive and negative affective responses to the “Solo” promotion and claims of rapid fashion in the overall research findings.

Furthermore, greenwashing indirectly affected green purchase intention through all the affective elements in the model. As Frijda et al. [27] have mentioned, products can generate positive and negative emotions. The clever marketing strategy of the fast fashion brand Solo created positive and negative affective responses. When greenwashing assertions are skillfully combined with product advantages, the perception of a favorable emotional reaction overshadows the negative, leading to an increased likelihood of acquiring the fast fashion brand’s goods. Furthermore, they overrate their capacity to identify instances of greenwashing and undervalue the potential risks to others, opting to accept or believe some aspects of the assertion. This led to optimism biases, as positive emotional reactions outweighed negative ones, hence increasing their propensity to purchase fast fashion goods.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

No previous research has examined Gen Z’s reactions to the promotional greenwashing practices of fast fashion brands through the lens of the C-A-B hypothesis. In opposition to established beliefs and research on greenwashing [13,14,16,48,50,56,69], our study offers three significant theoretical advances to the current greenwashing literature. Our first theoretical contribution to greenwashing research indicated that Gen Z consumers exhibited both positive and negative emotional reactions to fast fashion company greenwashing assertions. Despite feeling dubious and deceived by the greenwashing assertion, they proceeded with the purchase of the goods. A contributing factor to this unforeseen purchasing intention may be their indifference towards the environment. Moreover, when greenwashing assertions are infused with product advantages via astute strategy and aligned with the attributes of certain generational demands, the perception of positive emotional reaction surpasses the negative, hence influencing the purchase of the green product. This also creates optimism biases in Gen Z consumers. As Weinstein [28] has mentioned, optimism bias, a sort of cognitive bias, occurs when individuals see their decisions as secure based on their inherited values, irrespective of the potential adverse consequences for others. Gen Z sees “Solo” as a brand offering choices such as hiking opportunities and having the latest trendy products at affordable prices. They find value for money based on their core needs. This explains the paradoxical consumption behavior [94] of Gen Z consumers.

Furthermore, Gen Z consumers exhibit a limited ability to critically assess and evaluate greenwashing claims. The strong positive relationship between green trust and green purchase intention was further confirmed, as green trust demonstrated the highest unstandardized coefficient among all emotional factors influencing green buying behavior. A key theoretical contribution of this study to the greenwashing literature is that, despite Gen Z’s inclination to buy fast fashion clothing, they also express concerns about their personal image and the long-term environmental consequences of their consumption choices. These insights support the positive association between greenwashing and perceived environmental risk. Additionally, perceived risk related to green products was found to have a negative relationship with the desire to acquire green items across all emotional variables. Overall, the study explains why fast fashion brands remain a major market [2,38] despite being imbued with greenwashing phenomena 5, and why Gen Z remains a major consumer [2,15,18].

5.2. Managerial Implications

When the clever marketing strategy of fast fashion involves deceptive claims with product benefits, Gen Z U.S. consumers prefer to buy the product and are unable to detect greenwashing phenomena properly. According to the C-A-B theory, a positive response between the affective element and the behavior of personnel will lead to a predilection for the product and services of that brand, thus encouraging these brands to persist in making inflated environmental claims and facilitating the widespread propagation of greenwashing. One such scenario has been evident in fast fashion becoming the greatest turnover business around the world. It does not mean that consumers did not recognize greenwashing phenomena. Rather, when product benefits and deceptive claims are included, it creates attention deflection, and through C-A-B theory, we can explain this phenomenon. Policymakers impose stringent regulations on the advertising of fast fashion brands’ products with deceptive claims to curb the proliferation of greenwashing among Gen Z effectively. When Gen Z anticipated the potential environmental shortcomings of a product that might tarnish their eco-friendly reputation, they were reluctant to make a purchase. Gen Z was future-oriented regarding clothing and had image concerns. Policymakers should encourage fashion brands to be more future-oriented regarding product environmental performance and become goal-oriented toward long-term sustainability.

Given that the positive emotive reaction surpasses the negative affective response and motivates Gen Z consumers to purchase fast fashion apparel, fast fashion manufacturers need to emphasize product advantages integrated with sustainability attributes. Instead of misleading sustainability claims, reasonable pricing and a clear sustainable message approach will foster a long-term customer base for fast fashion brands. Despite the fact that Gen Z is the latest generation, their inclination toward fast fashion garments may evolve in accordance with their evolving lifestyle and age. Therefore, in the future, the fast fashion brand must maintain its consumer base by emphasizing sustainability messages rather than deceptive greenwashing claims. Moreover, there is evidence of optimism biases, a cognitive distortion whereby individuals overstate their ability to detect instances of greenwashing, prioritize their demands, and minimize the potential risks to others. Consequently, it is imperative to educate Gen Z consumers about sustainability to foster a sense of responsibility for the environment and associated risks for others, in addition to their requirements.

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

This research intends to elucidate, using the C-A-B theory, the buying decision-making processes of Gen Z customers in the United States when confronted with the promotional assertions of fast fashion businesses. The study’s results indicated that Gen Z consumers exhibited both favorable and unfavorable emotional reactions to the greenwashing assertions of fast fashion businesses. The impression of a favorable emotional reaction surpasses the negative when greenwashing assertions are integrated with product advantages via a creative approach, hence promoting the purchase of the green product. This elucidates the contradictory purchasing patterns of Gen Z and articulates the rationale for the sustained prominence of fast fashion firms in the market, despite their association with greenwashing. Despite Gen Z’s propensity to acquire fast fashion apparel, they express apprehensions over the environmental sustainability of these products and their impact on personal image. Policymakers may gain fresh insights to understand the greenwashing tactics used by fast fashion manufacturers. Through the application of the C-A-B theory, we were able to elucidate the reasons why fast fashion is a thriving industry and why Gen Z continues to be a significant consumer despite the allegations of greenwashing that persist in the fast fashion industry.

Considering that the positive emotional response outweighs the negative affective reaction and drives Gen Z consumers to acquire fast fashion garments, fast fashion producers must highlight product benefits combined with sustainability features. Despite being the youngest generation, Gen Z’s preferences for fast fashion apparel may evolve as they mature and their lifestyles change. Consequently, the fast fashion business must retain this customer by advocating sustainability messaging instead of misleading greenwashing assertions in the future. Because of the evident optimism biases, it is essential to educate Gen Z customers about sustainability to cultivate a feeling of environmental responsibility and awareness of the risks posed to others, alongside their own needs.

Our study has limitations. The quantity of male participation surpassed that of female participants. In addition, only American Gen Z individuals and rapid fashion were considered. Greenwashing may induce a “spillover effect” among customers. Research is required to examine whether the phenomenon of greenwashing by fast fashion firms deters customers from purchasing luxury or slow fashion goods. Furthermore, developing countries are known as manufacturing hubs, and developed countries as consumption hubs. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct cross-cultural studies across these two hubs to measure the greenwashing perception of fast fashion brands among consumers. Furthermore, greenwashing is a complex phenomenon, and it has evolved diverse and creative tactics over time; therefore, a mixed-method study is needed for a deeper understanding of the greenwashing phenomena in fast fashion brands.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N.H. and C.L.; methodology, M.N.H.; software, M.N.H.; validation, M.N.H. and C.L.; formal analysis, M.N.H.; investigation, M.N.H.; resources, M.N.H.; data curation, M.N.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N.H.; writing—review and editing, C.L.; visualization, M.N.H.; supervision, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Louisiana State University (protocol code IRBAM-24-0179 and date of approval 4 March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Earth.org. Fast Fashion and Its Environmental Impact. 2024. Available online: https://earth.org/fast-fashions-detrimental-effect-on-the-environment/ (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Estrada, M. Meet the Gen Z-ers Slowing Down Fast Fashion by Promoting Sustainable Clothing. NBC 7 San Diego. 2024. Available online: https://www.nbcsandiego.com/news/national-international/gen-z-ers-fast-fashion-sustainable-clothing/3495333/#:~:text=24/7%20San%20Diego%20news,end%20up%20in%20a%20landfill (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Li, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, M.; Guan, D.; Yang, Z. The carbon footprint of fast fashion consumption and mitigation strategies—A case study of jeans. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cachon, G.P.; Swinney, R. The value of fast fashion: Quick response, enhanced design, and strategic consumer behavior. Manag. Sci. 2011, 57, 778–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, S.; Mohan, V. Consumer perceptions of greenwashing: Lessons learned from the fashion sector in the UAE. Asian J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 11, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, T.Z.; Stagner, J. Fast fashion-wearing out the planet. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 80, 856–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimock, M. Defining generations: Where Millennials end and Generation Z begins. Pew Res. Cent. 2019, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, P. Consumer attitude towards sustainability of fast fashion products in the UK. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, V. Resident Population in the United States in 2023, by Generation. Statista. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/797321/us-population-by-generation/ (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Garcia-Ortega, B.; Galan-Cubillo, J.; Llorens-Montes, F.J.; de-Miguel-Molina, B. Sufficient consumption as a missing link toward sustainability: The case of fast fashion. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 399, 136678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majláth, M. The effect of greenwashing information on ad evaluation. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linckens, S.; Horn, C.; Perret, J.K. Greenwashing in the Fashion Industry—The Flipside of the Sustainability Trend from the Perspective of Generation Z; BoD–Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Shi, B. Impact of Greenwashing Perception on Consumers’ Green Purchasing Intentions: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Sheng, T.; Zhou, X.; Shen, C.; Fang, B. How does young consumers’ greenwashing perception impact their green purchase intention in the fast fashion industry? An analysis from the perspective of perceived risk theory. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojdyla, W.; Chi, T. Decoding the Fashion Quotient: An Empirical Study of Key Factors Influencing US Generation Z’s Purchase Intention toward Fast Fashion. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promalessy, R.; Handriana, T. How does greenwashing affect green word of mouth through green skepticism? Empirical research for fast fashion Business. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2389467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, B.; Santos, C.; Abdirahman, S.; Power, A.; Uddin, Z. EcoFashion Scanner: Bridging the Gen Z and Millennial ‘Green Gap’ by Facilitating Sustainable Fashion Consumption Behaviours. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 11–16 May 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zimand-Sheiner, D.; Lissitsa, S. Generation Z-factors predicting decline in purchase intentions after receiving negative environmental information: Fast fashion brand SHEIN as a case study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 81, 103999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.N.; Lang, C. Generation Z perception regarding fast fashion brand greenwashing phenomena. In Proceedings of the 81st International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference Proceedings, Long Beach, CA, USA, 19–23 November 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicosia, F.M. Consumer Decision Processes; Marketing and Advertising Implications; Prentice Hall: Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, R.Y.; Lau, L.B. Antecedents of green purchases: A survey in China. J. Consum. Mark. 2000, 17, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Batra, R. Assessing the role of emotions as mediators of consumer responses to advertising. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 14, 404–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbaix, C.; Pham, M.T. Affective reactions to consumption situations: A pilot investigation. J. Econ. Psychol. 1991, 12, 325–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, R.A. Product/consumption-based affective responses and postpurchase processes. J. Mark. Res. 1987, 24, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmet, P.M. Faces of product pleasure: 25 positive emotions in human-product interactions. Int. J. Des. 2012, 6, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Frijda, N.H.; Kuipers, P.; Ter Schure, E. Relations among emotion, appraisal, and emotional action readiness. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.D. Unrealistic optimism about future life events. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bick, R.; Halsey, E.; Ekenga, C.C. The global environmental injustice of fast fashion. Environ. Health 2018, 17, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Bustamante-Ventisca, M.; Carcelén-García, S.; Díaz-Soloaga, P.; Kolotouchkina, O. Greenwashing perception in Spanish fast-fashion brands’ communication: Modelling sustainable behaviours and attitudes. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2024, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onclusive. Construir la Reputación de Marca Evitando el Riesgo de Greenwashing. 2023. Available online: https://onclusive.com/es/recursos/informes/construir-la-reputacion-de-marca-evitando-el-riesgo-de-greenwashing/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- The Ultimate Guide to Greenwashing. 2019. Available online: https://gogreenproject.com.au/the-ultimate-guide-to-greenwashing/ (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Feria, M. Is H&M Sustainable and Ethical? 2023. Available online: https://sustainly.com/hm-sustainable-ethical/ (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Seigle, L. Am I a Fool to Expect More Than Corporate Greenwashing? 2016. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/apr/03/rana-plaza-campaign-handm-recycling (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- Park, H.; Kim, Y.-K. Proactive versus reactive apparel brands in sustainability: Influences on brand loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brain, E. H&M Norway Called out for “Greenwashing” Conscious Collection Marketing. 2019. Available online: https://hypebeast.com/2019/8/h-m-conscious-collection-greenwashing-sustainability-norwegian-consumer-authority (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Smith, P. Generation Z Fashion in the United States—Statistics & Facts. Statista. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/9997/generation-z-fashion-in-the-united-states/#topicOverview/ (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Smith, P. Fast Fashion Market Value Forecast Worldwide from 2022 to 2027. Statista. 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1008241/fast-fashion-market-valueforecast-worldwide2023/ (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Ribeiro, M.A.; Prayag, G. Perceived quality and service experience: Mediating effects of positive and negative emotions. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.-C. Understanding content sharing on the internet: Test of a cognitive-affective-conative model. Online Inf. Rev. 2020, 44, 1289–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Kim, D.J.; Wachter, K. A study of mobile user engagement (MoEN): Engagement motivations, perceived value, satisfaction, and continued engagement intention. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 56, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence consumer loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwahk, K.-Y.; Ahn, H.; Ryu, Y.U. Understanding mandatory IS use behavior: How outcome expectations affect conative IS use. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 38, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlena, W.J.; Holbrook, M.B. The varieties of consumption experience: Comparing two typologies of emotion in consumer behavior. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaofei, Z.; Guo, X.; Ho, S.Y.; Lai, K.-h.; Vogel, D. Effects of emotional attachment on mobile health-monitoring service usage: An affect transfer perspective. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Freitas Netto, S.V.; Sobral, M.F.F.; Ribeiro, A.R.B.; Soares, G.R.d.L. Concepts and forms of greenwashing: A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-H. Greenwash and green trust: The mediation effects of green consumer confusion and green perceived risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, S.; Martínez, M.P.; Correa, C.M.; Moura-Leite, R.C.; Da Silva, D. Greenwashing effect, attitudes, and beliefs in green consumption. RAUSP Manag. J. 2019, 54, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.H.; Yang, Z.; Nguyen, N.; Johnson, L.W.; Cao, T.K. Greenwash and green purchase intention: The mediating role of green skepticism. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussin, H.; Wahid, N.A. Conceptualizing Customer Experience in Organic Food Purchase Using Cognitive-Affective-Behavior Model. J. Gov. Integr. 2023, 6, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boush, D.M.; Friestad, M.; Rose, G.M. Adolescent skepticism toward TV advertising and knowledge of advertiser tactics. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreh, M.R.; Grier, S. When is honesty the best policy? The effect of stated company intent on consumer skepticism. J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 349–356. [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi, R.; Schuchard, R.; Shea, L.; Townsend, S. Understanding and Preventing Greenwash: A Business Guide; Futerra Sustainability Communications: London, UK, 2009; pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Self, R.M.; Self, D.R.; Bell-Haynes, J. Marketing tourism in the Galapagos Islands: Ecotourism or greenwashing? Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. (IBER) 2010, 9, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aji, H.M.; Sutikno, B. The extended consequence of greenwashing: Perceived consumer skepticism. Int. J. Bus. Inf. 2015, 10, 433–468. [Google Scholar]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Skarmeas, D. Gray shades of green: Causes and consequences of green skepticism. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 144, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomering, A.; Johnson, L.W. Advertising corporate social responsibility initiatives to communicate corporate image: Inhibiting scepticism to enhance persuasion. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2009, 14, 420–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyilasy, G.; Gangadharbatla, H.; Paladino, A. Perceived greenwashing: The interactive effects of green advertising and corporate environmental performance on consumer reactions. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermiller, C.; Spangenberg, E.; MacLachlan, D.L. Ad skepticism: The consequences of disbelief. J. Advert. 2005, 34, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, J.J.; Gershoff, A.D. Betrayal aversion: When agents of protection become agents of harm. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2003, 90, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalin, L.; Fengjie, J. The influence of enterprise negative events on brand extension evaluation: The mediating effect of perceived sense of betrayal. Manag. Rev. 2016, 28, 129. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Li, J.; Liao, S.; Wen, L. Study of the relationship between environmental values and green purchasing behavior: The mediating effect of environmental attitude. J. Dalian Univ. Technol 2010, 31, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Peasley, M.C.; Woodroof, P.J.; Coleman, J.T. Processing contradictory CSR information: The influence of primacy and recency effects on the consumer-firm relationship. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 172, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Enhance green purchase intentions: The roles of green perceived value, green perceived risk, and green trust. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, J.P.; Ryan, M.J. An investigation of perceived risk at the brand level. J. Mark. Res. 1976, 13, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.P.; Heide, J.B.; Cort, S.G. Information asymmetry and levels of agency relationships. J. Mark. Res. 1998, 35, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, V.W. Consumer perceived risk: Conceptualisations and models. Eur. J. Mark. 1999, 33, 163–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akturan, U. How does greenwashing affect green branding equity and purchase intention? An empirical research. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2018, 36, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, M.S.; Roche, C. What the’Green’consumer wants. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2009, 50, 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, S.M. Antecedents of green purchase behavior: An examination of collectivism, environmental concern, and PCE. ACR N. Am. Adv. 2005, 32, 592. [Google Scholar]

- Tarabieh, S. The impact of greenwash practices over green purchase intention: The mediating effects of green confusion, Green perceived risk, and green trust. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2021, 11, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.M.M.R.; Yifei, L.; Bhutto, M.Y.; Ali, R.; Alam, F. The influence of consumption values on green purchase intention: A moderated mediation of greenwash perceptions and green trust. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2019, 13, 826–848. [Google Scholar]

- Weisstein, L.F.; Asgari, M.; Siew, S.-W. Price presentation effects on green purchase intentions. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2014, 23, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drennan, J.; Sullivan, G.; Previte, J. Privacy, risk perception, and expert online behavior: An exploratory study of household end users. J. Organ. End User Comput. (JOEUC) 2006, 18, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Darden, W.R.; Griffin, M. Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 20, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G.; Bredahl, L.; Brunsø, K. Consumer perception of meat quality and implications for product development in the meat sector—A review. Meat Sci. 2004, 66, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, D.; Malik, H.A.; Liu, Y.; Elashkar, E.E.; Shoukry, A.M.; Khader, J. Battling for consumer’s positive purchase intention: A comparative study between two psychological techniques to achieve success and sustainability for digital entrepreneurships. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 665194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wren, B. Sustainable supply chain management in the fast fashion Industry: A comparative study of current efforts and best practices to address the climate crisis. Clean. Logist. Supply Chain 2022, 4, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S. From “green blur” to ecofashion: Fashioning an eco-lexicon. Fash. Theory 2008, 12, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailer, A.; Wilfing, H.; Straus, E. Greenwashing and bluewashing in black Friday-related sustainable fashion marketing on Instagram. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Breukelen, G.J. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). In Encyclopedia of Research Design; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.B.; Chai, L.T. Attitude towards the environment and green products: Consumers’ perspective. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2010, 4, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, J.M.; Lance, C.E. What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M. Common method bias in marketing: Causes, mechanisms, and procedural remedies. J. Retail. 2012, 88, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, C.M.; Simmering, M.J.; Atinc, G.; Atinc, Y.; Babin, B.J. Common methods variance detection in business research. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Hartman, N.; Cavazotte, F. Method variance and marker variables: A review and comprehensive CFA marker technique. Organ. Res. Methods 2010, 13, 477–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y. Assessing method variance in multitrait-multimethod matrices: The case of self-reported affect and perceptions at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990, 75, 547–560. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R. Multivariate Data Analysis; Cengage Learn: Hampshire, UK, 2019; Volume 633. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, H.; Homburg, C. Applications of structural equation modeling in marketing and consumer research: A review. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1996, 13, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Knight, J.G.; Zhang, H.; Mather, D.; Tan, L.P. Consumer scapegoating during a systemic product-harm crisis. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 1270–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herron, A. The Intention Gap: When Buying and Beliefs Don’t Match. FASHION DIVE. 2023. Available online: https://www.fashiondive.com/news/sustainable-fashion-consumer-demographics-gen-z/650864/ (accessed on 26 August 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).