The findings of this study are discussed under two headings in this section: first, through a theoretical lens to highlight the theoretical implications; and second, from a managerial perspective to provide actionable, practical insights.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

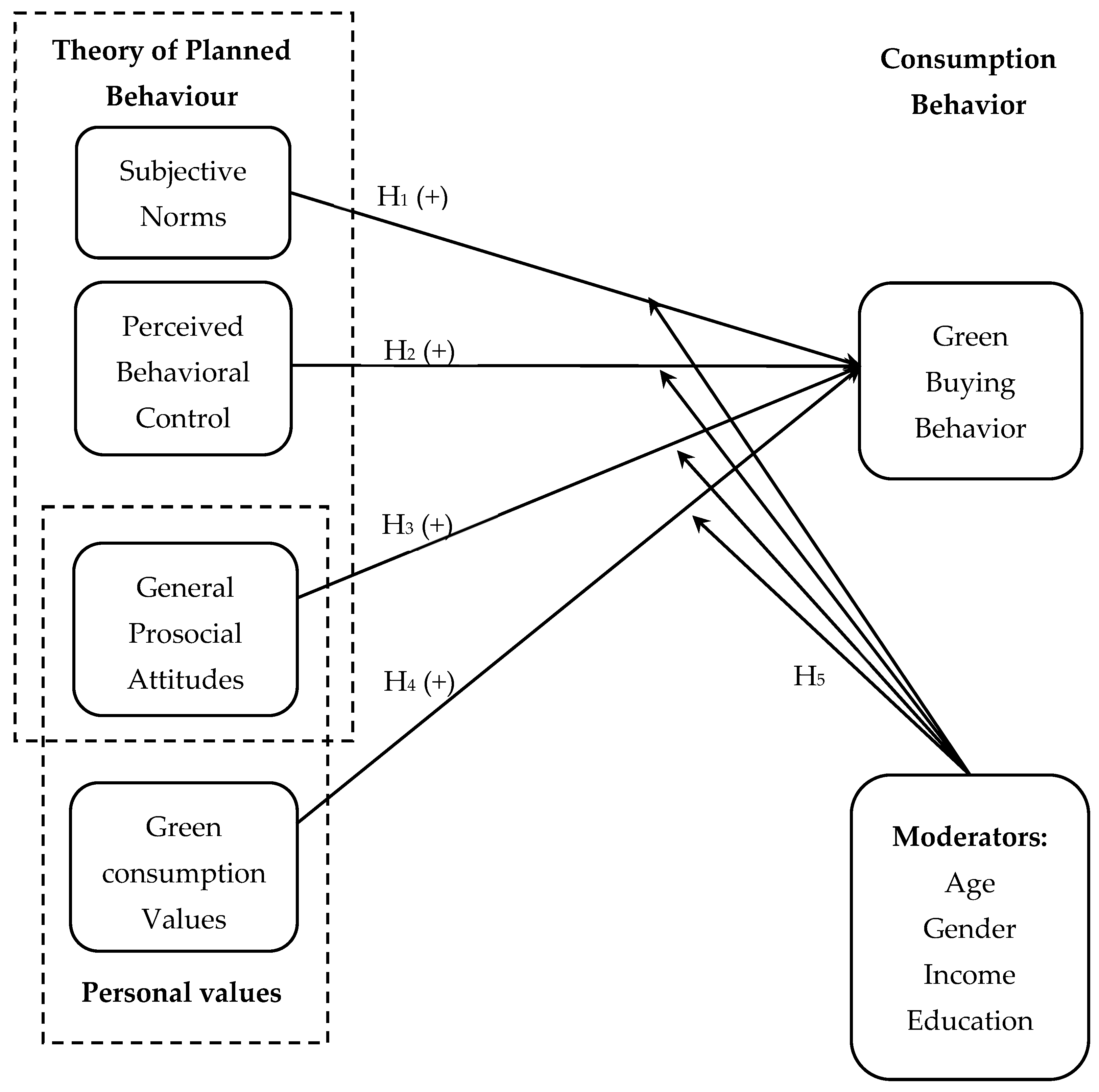

This study offers several theoretical implications that challenge and expand existing consumer behavior frameworks, particularly the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), in sustainability contexts. This study extends the TPB framework by integrating Green Consumption Values (GRCV) as a value-based antecedent. GRCV functions as a moral and identity-related driver that can influence behavioral intention, complementing the attitudinal and normative pathways already established within TPB. While this study focuses on the UK, its findings may have broader relevance to other countries with similar socioeconomic and cultural characteristics. As a developed economy, the UK shares key attributes with other Western nations, such as high levels of environmental awareness, widespread access to sustainable products, and a growing emphasis on ethical consumption.

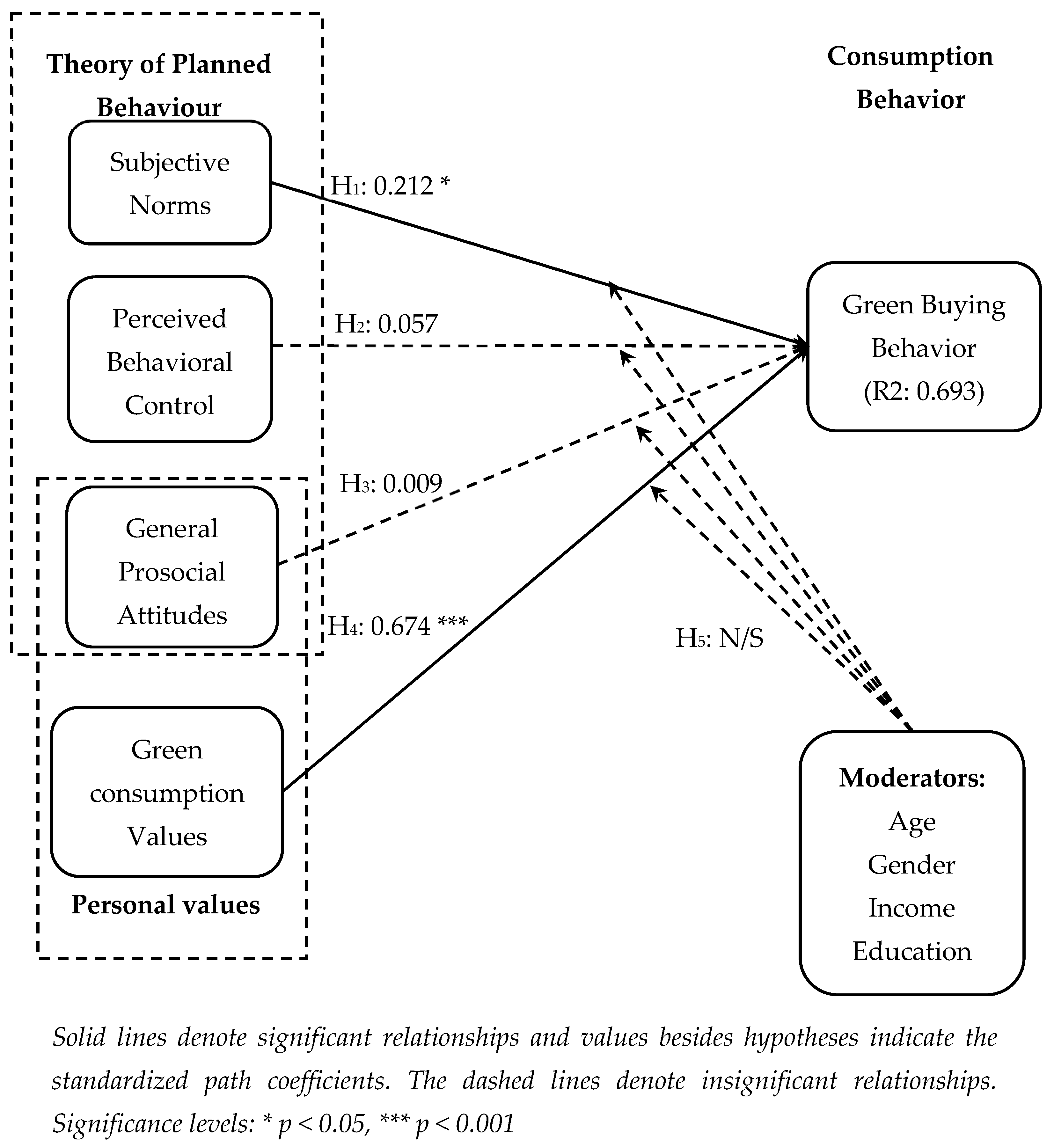

First, the lack of a significant relationship between perceived behavioral control and green buying behavior questions the universal applicability of TPB in explaining eco-friendly consumption. While PBEC is typically considered a key driver in TPB, its non-significance here echoes findings of certain studies [

36,

85] and suggests that consumers’ perceptions of control may be less relevant when strong intrinsic motivations, such as green consumption values, are present. Alternatively, PBEC may be more relevant in high-cost or effort-intensive consumption contexts.

Second, the strong positive relationship between green consumption values and green buying behavior reinforces the significance of personal values in driving eco-friendly choices. This aligns with existing literature suggesting that individuals with high GRCV are more likely to prioritize sustainability in their consumption decisions [

18,

63,

64]. The substantial effect size (f

2 = 0.935) emphasizes that intrinsic values far outweigh other determinants, positioning GRCV as a cornerstone in theoretical models explaining green behavior. These insights stress the need to integrate similar individual factors into existing consumer behavior models (e.g., TPB) for promoting sustainable product adoption.

Third, the weaker yet positive influence of social factors highlights that while peer and societal pressures contribute to green purchasing behavior, their impact is relatively limited compared to intrinsic motivations (i.e., GRCV). This distinction underscores the need for theoretical frameworks to differentiate between internalized value-driven behavior and externally motivated actions, particularly in contexts of sustainable consumption.

Fourth, the non-significant impact of prosocial attitudes on GBB among the total sample deviates from the extant literature, which often links altruistic motivations with green purchasing. This finding suggests that while prosocial attitudes may reflect a general concern for others, they do not necessarily translate into actionable, eco-friendly behavior. However, the moderating role of age in this relationship, with significant effects observed among younger respondents, invites further exploration of contextual and demographic factors. This finding points to the importance of considering how generational differences and other mediators, such as environmental knowledge or lifestyle, might shape the relationship between prosocial attitudes and green buying behavior.

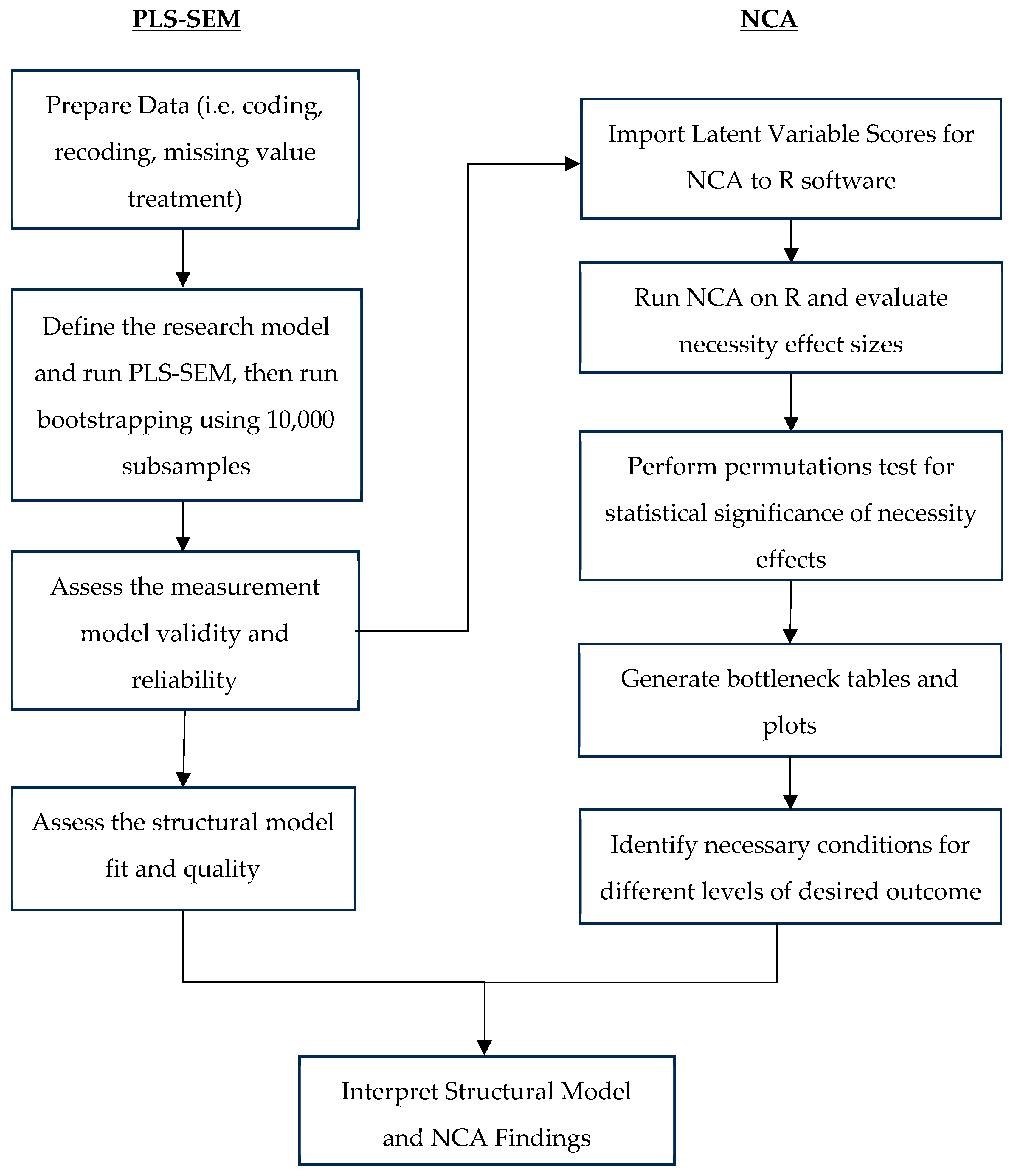

Fifth, Necessary Condition Analysis (NCA) revealed that both GRCV and PBEC are essential for achieving higher levels of green buying behavior, even if PBEC lacks direct predictive power. The weak effect size of PBEC as a necessary condition (d = 0.10) suggests that consumers require a baseline level of perceived capability to act on their green values. This finding aligns with the logic of non-compensatory causality, where certain enablers (like perceived behavioral control) must be present to allow behavior, even if they do not drive it directly. In this case, individuals may need to feel capable of acting (e.g., having access to sustainable products or feeling confident in their ability to assess green claims), but once that threshold is met, further increases in perceived control do not enhance the likelihood of acting green. This supports the interpretation that PBEC functions more as a “gatekeeper” rather than a “motivator” in the green purchasing process. PBEC acts as a boundary condition that constrains action only when absent. This finding highlights the importance of integrating necessity-based analyses into sustainability research, offering a complementary perspective to conventional path models.

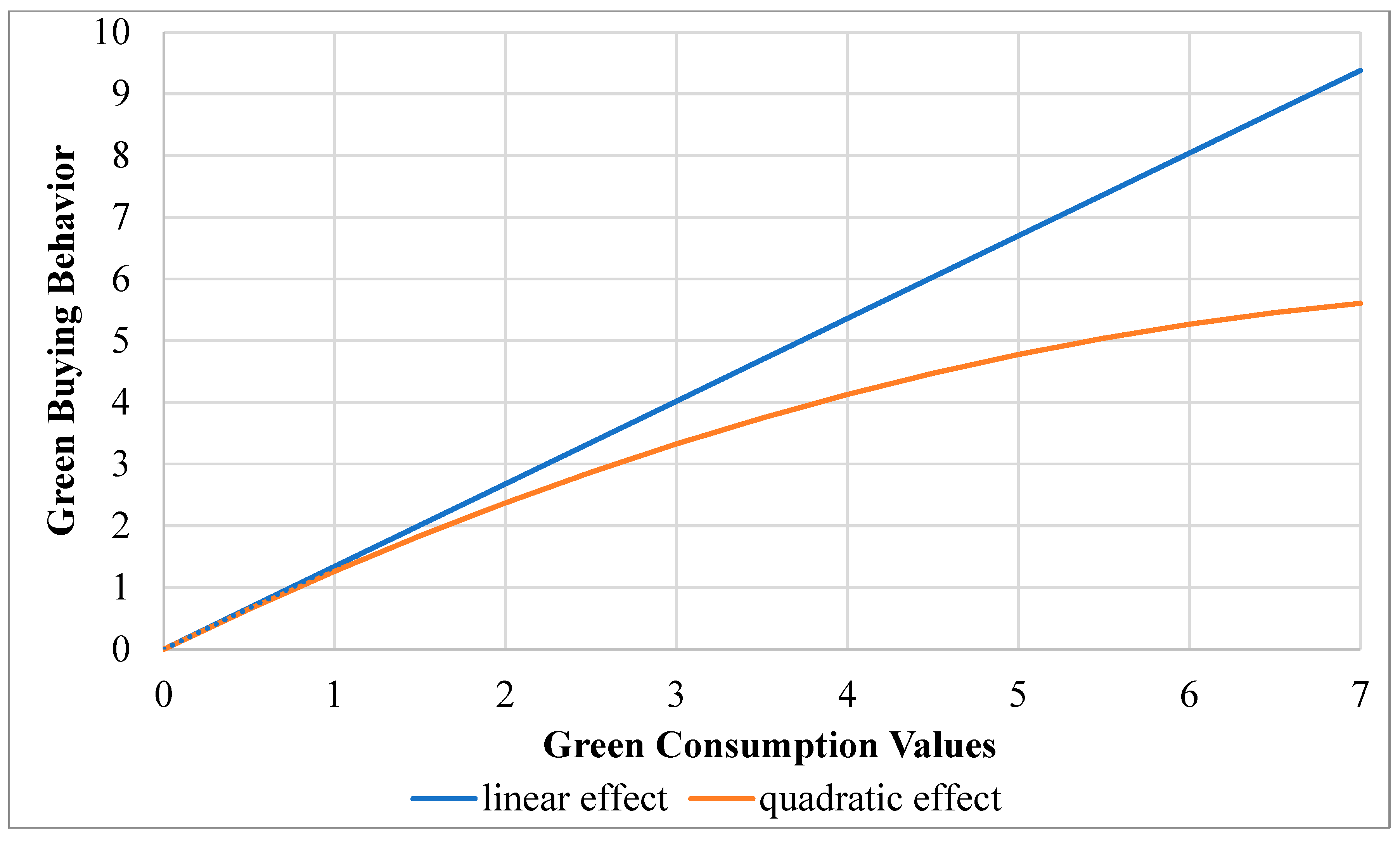

Sixth, the identified logarithmic relationship between GRCV and green buying behavior supports emerging interest in non-linear models within consumer behavior research [

90,

91,

92,

96]. Initially, individuals with low to moderate green values show steep increases in green buying behavior as their values strengthen. However, beyond a certain point, further intensification of GRCV yields diminishing behavioral gains. At high GRCV levels, intrinsic satisfaction from “doing enough” may attenuate the perceived urgency to escalate green purchases, a phenomenon consistent with cognitive dissonance theory triggered by value saturation and motivational plateaus [

91]. Once consumers internalize sustainability as a core personal value and adopt key green behaviors, additional value reinforcement may no longer significantly alter their consumption patterns [

97]. This pattern resembles satisficing behavior in decision theory [

98], wherein individuals feel they have ’done enough’ once a certain level of responsible behavior is achieved. The observed behavioral plateau aligns with the concept of moral saturation, where incremental increases in moral or ethical concern fail to produce proportional behavioral changes [

96]. This finding warrants further exploration of the diminishing returns phenomenon in value-driven behaviors, particularly in sustainability studies.

Finally, the findings highlight the limited moderating role of demographics. The absence of significant moderation effects by gender, education, and income suggests that green buying behavior and its antecedents are consistent across diverse consumer groups but differ between generations. This finding challenges the traditional focus on demographics in segmentation strategies, shifting theoretical attention towards psychographic and behavioral variables as stronger predictors.

5.2. Managerial and Practical Implications

For practitioners, the results underscore the critical role of fostering green consumption values among consumers. Marketing strategies should thus focus on value-driven messaging that resonates with consumers’ existing environmental values while seeking to cultivate such values in broader audiences. Educational campaigns, green certifications, and transparency in sustainable practices can help reinforce GRCV as a driver of green purchasing.

The diminishing return effect of GRCV and the NCA results suggest that efforts to promote green products should prioritize consumers with moderate levels of GRCV, as they are most likely to respond to interventions. Tailored campaigns that resonate with this group (e.g., emphasizing product authenticity, highlighting environmental impact, or leveraging relatable green role models) could maximize behavior change without expending excessive resources on individuals with already high GRCV. Marketing efforts should diversify messaging at higher levels of GRCV. For highly committed green consumers, brands may need to highlight other value-added aspects (e.g., product quality or community impact) that enhance the appeal of eco-friendly products beyond mere green credentials.

The age-related differences in green buying behavior offer valuable insights for tailoring marketing campaigns. For older consumers, campaigns emphasize the alignment of eco-friendly products with deeply held personal values, underscoring themes of consistency, responsibility, and legacy. Conversely, campaigns targeting younger audiences should focus on their altruistic tendencies and collective aspirations. Messaging should underscore how their individual choices contribute to global sustainability, appealing to their sense of purpose and shared responsibility for creating a better future.

The findings also indicate a strategic benefit in leveraging social influence as a supporting element. While not as strong as GRCV, social influence can act as a complementary factor, suggesting that companies might benefit from social proof tactics, such as influencer partnerships or community-based initiatives, to reinforce green buying behavior.

Finally, the findings indicate that perceived behavioral control is a necessary but not sufficient condition for green buying behavior, suggesting that consumers must feel empowered to act sustainably, but this alone does not guarantee action. To design effective interventions, it is critical to enhance PBEC in a way that complements rather than undermines intrinsic motivations like green consumption values. Communications may highlight how individual actions contribute to broader environmental goals, reinforcing a sense of agency. Providing diverse options for sustainable products may allow consumers to make eco-friendly decisions aligned with their personal preferences, preserving autonomy so that sustainable consumption feels like an active, value-driven choice rather than an obligation.

5.3. Limitations and Future Scope

While this study offers valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge its limitations, primarily rooted in its methodology. This study employed a convenience sampling method, primarily distributing the survey through social media platforms (i.e., LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter). As a cross-sectional survey reliant on self-reported perceptions, there’s potential for a gap between stated intentions and actual consumer behavior. Inherent to the methodology, biases such as social conformity and acquiescence may influence findings as well. Furthermore, the non-random sampling method employed (i.e., convenience sampling), though common in cross-sectional research, may limit the generalizability of the findings. The use of several social media platforms to collect data facilitated access to a broad audience, yet it may have introduced sampling bias, favoring a younger, more digitally active respondent profile. Future studies employing larger, more diverse samples obtained through stratified sampling and using expanded recruitment channels will reduce such platform-based biases and demographic skewness. Also, this methodology does not account for considering changing perceptions, attitudes, or intentions over time.

The prosocial attitude construct was measured using a general scale rather than one specific to environmental behaviors. While this aligns with previous studies examining broad value orientations, a more domain-specific measure might better capture the environmental intent behind prosocial behavior. This suggests an opportunity for future research to refine construct alignment.

Our study opens up several promising avenues for future research. Incorporating behavioral data, such as tracking actual purchase behavior or using experimental designs, could provide a more objective measure of green buying behavior. Observational or experimental methods would also enable comparison between stated intentions and actual behavior. Future studies could adopt longitudinal or quasi-experimental methods such as difference-in-differences (DID) for causal inference. Moreover, the insignificant effect of PBEC and pro-social attitudes on green buying behavior presents an area to focus on. Future research could consider these non-significant relationships by exploring potential mediators (e.g., trust in green claims) or moderators (e.g., product price, product attributes, perceived effort, cultural factors). Studies that focus on a particular product group will shed light on context-specific influences. Experimental studies could also test under what conditions PBEC or pro-social attitudes become more influential.

Moreover, addressing barriers highlighted in existing literature could provide valuable insights. These include a lack of variety and availability in products, higher price points, and consumer distrust towards brands’ sustainability claims due to greenwashing [

11,

99,

100]. Examining how these factors interact with green buying behavior may offer important insights into effective communication strategies for promoting such behavior.

Finally, future research may also consider what specific cultural or societal factors may amplify or dampen the generational differences detected in this study. Given that sustainability perceptions and green purchase behavior may differ by cultural context, comparative studies across diverse geographic regions would enhance the external validity of the model. The barriers younger consumers face in acting on GRCV, such as economic constraints or competing priorities, may be explored. Moreover, how these differences might evolve as younger cohorts age and accumulate life experiences could deepen our understanding of how age shapes sustainable consumption over time.