Building Sustainable Teaching Careers: The Impact of Diversity Practices on Middle School Teachers’ Job Satisfaction in China and the United States

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Global Focus on Diversity Practices in Education

1.2. Female Middle School Teachers in Diverse Environments

1.3. Varying Impacts of Diversity Practices on Job Satisfaction

1.4. The Need for Cross-Cultural Comparison Between the United States and China

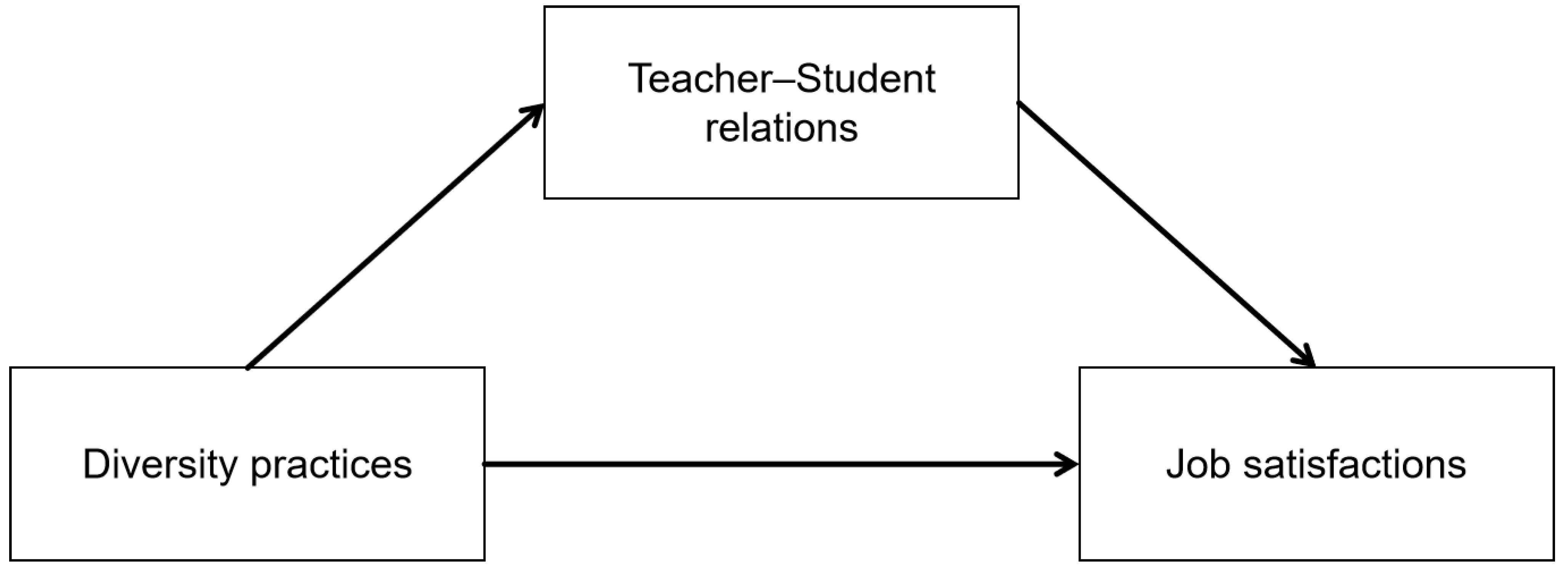

1.5. The Mediating Role of Teacher–Student Relationships in the Link Between School Diversity Practices and Teacher Job Satisfaction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Diversity in Teaching Practices in the United States and China

2.2. Job Satisfaction, Teachers’ Job Satisfaction, and Its Importance

2.3. Factors Influencing Teachers’ Job Satisfaction

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Job Demands–Resources Model and Job Satisfaction in Teachers’ Workplace Experiences

3.2. Experiences Hypothesized Effects Based on the JD–R Model

4. The Present Study

4.1. Research Gaps

4.2. Hypotheses

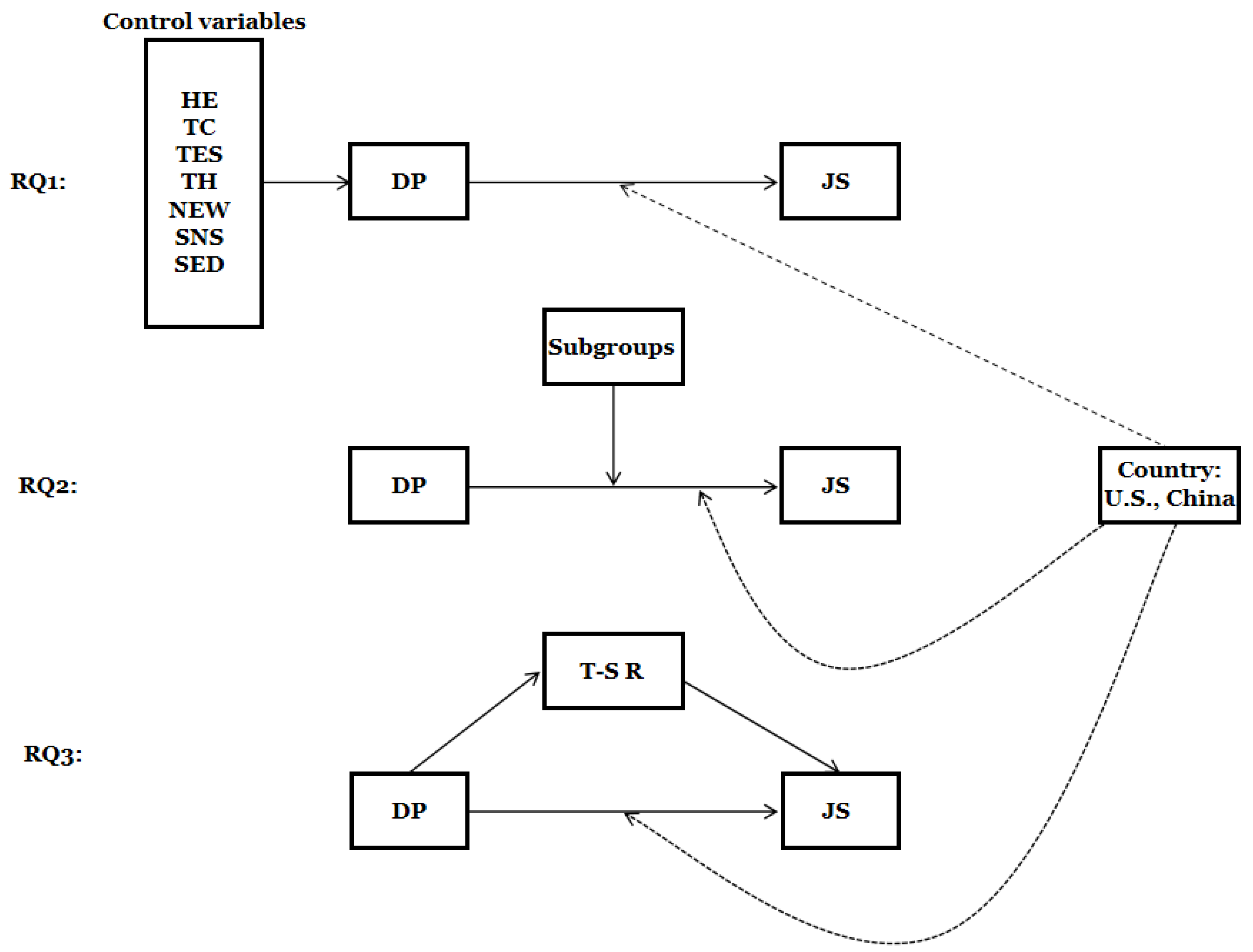

4.3. Research Question

5. Methods

5.1. Data

5.2. Variables

5.2.1. Dependent Variable: Teachers’ Job Satisfaction

5.2.2. Independent Variable: Diversity Practices

5.2.3. Control Variables

5.2.4. Mediating Variable: Teaching–Student Relations

5.3. Analytical Strategy

5.3.1. Regression Analysis

5.3.2. Shapley Value Decomposition

5.3.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.3.4. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

6. Results

6.1. Results of the Regression Model

6.2. Results of the Shapley Value Decomposition

6.3. Results of Heterogeneity Analysis

6.3.1. Gender

6.3.2. Age

6.4. Results of the Robustness Test

6.5. Results of the SEM

7. Discussion

8. Implication

8.1. Theoretical Implications

8.2. Practical Implications

8.2.1. Adapting Diversity Practices

8.2.2. Differentiated Support by Teacher Demographics

8.2.3. Enhancing Teacher–Student Relationships

9. Limitations and Future Directions

9.1. Lack of a Ground-Level Implementation Context

9.2. Exclusion of Sexual Identity Variables

9.3. Theoretical Scope and Unmeasured Mediating Variables

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Messiou, K.; Ainscow, M.; Echeita, G.; Goldrick, S.; Hope, M.; Paes, I.; Sandoval, M.; Simon, C.; Vitorino, T. Learning from differences: A strategy for teacher development in respect to student diversity. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2016, 27, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markey, K.; O’Brien, B.; Kouta, C.; Okantey, C.; O’Donnell, C. Embracing classroom cultural diversity: Innovations for nurturing inclusive intercultural learning and culturally responsive teaching. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2021, 16, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheared, V. Creating inclusive learning spaces for a diverse world. In Inclusive Education in Bilingual and Plurilingual Programs; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, C.A.; Chisom, O.N.; Adeniyi, I.S. Cultural competence in education: Strategies for fostering inclusivity and diversity awareness. Int. J. Appl. Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 6, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Educating Teachers for Diversity: Meeting the Challenge, Educational Research and Innovation; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, S. What is diversity? Am. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 47, 292–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M. Diversity and equity: A global education challenge. N. Z. J. Educ. Stud. 2016, 51, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Welcoming Diversity in the Learning Environment: Teachers’ Handbook for Inclusive Education; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Equity and Inclusion in Education: Finding Strength Through Diversity; OECD: Pari, France, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funds for NGOs. Promoting Inclusive Education for Marginalized Communities Worldwide. 2024. Available online: https://www.fundsforngos.org/proposals/promoting-inclusive-education-for-marginalized-communities-worldwide/ (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Hue, M.T.; Kennedy, K.J. Creating culturally responsive environments: Ethnic minority teachers’ constructs of cultural diversity in Hong Kong secondary schools. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2014, 34, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourdavood, R.G.; Yan, M. Becoming critical: In-service teachers’ perspectives on multicultural education. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2020, 19, 112–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnet, M. Cultural diversity and curriculum. Panauti J. 2024, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, A.H. Exploring organisational perspectives on implementing educational inclusion in mainstream schools. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2012, 16, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombardelli, O. Inclusive education and its implementation: International practices. Educ. Self Dev. 2020, 15, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerna, L.; Mezzanotte, C.; Rutigliano, A.; Brussino, O.; Santiago, P.; Borgonovi, F.; Guthrie, C. Promoting Inclusive Education for Diverse Societies: A Conceptual Framework; OECD Education Working Papers; OECD: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redding, C.; Nguyen, T.D. The effects of Race to the Top on teacher qualifications, work environments, and job attitudes. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 2023, 46, 237–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, M.P.; Sartain, L. What explains the race gap in teacher performance ratings? Evidence from Chicago Public Schools. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 2020, 43, 60–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, A.S.; Ngwenya, K. Challenges in the implementation of inclusive education at Elulakeni cluster primary schools in Shiselweni district of Swaziland. Eur. Sci. J. 2015, 11, 246–261. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, U.; Armstrong, A.C.; Merumeru, L.; Simi, J.; Yared, H. Addressing barriers to implementing inclusive education in the Pacific. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 23, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpu, Y.; Adu, E.O. The challenges of inclusive education and its implementation in schools: The South African perspective. Perspect. Educ. 2021, 39, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, H.; Farinde-Wu, A. Navigating the journey to culturally responsive teaching: Lessons from the success and struggles of one first-year, Black female teacher of Black students in an urban school. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 60, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boring Shoff, B.D. Let’s Talk About It: Bridging the Gap Between Diverse Students and Their White Teachers. Ph.D. Thesis, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chancellor, J. Urban Teacher’s Perspectives on Teaching Diverse Students. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Berryman, M. Teacher-student relationships. In Oxford Bibliographies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conderman, G. Middle school co-teaching: Effective practices and student reflections. Middle Sch. J. 2011, 42, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaty-O’Ferrall, M.E.; Green, A.; Hanna, F. Classroom management strategies for difficult students: Promoting change through relationships. Middle Sch. J. 2010, 41, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, E.D.; Bennett, K.D. Implementing culturally responsive positive behavior interventions and supports in middle school classrooms. Middle Sch. J. 2015, 46, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordu, A. The effects of diversity management on job satisfaction and individual performance of teachers. Educ. Res. Rev. 2016, 11, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D.; Brookhart, S.; Loadman, W.E. Realities of teaching in racially/ethnically diverse schools. Urban Educ. 1999, 34, 114–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardif-Grenier, K.; Goulet, M.; Archambault, I.; McAndrew, M. Elementary school teachers’ openness to cultural diversity and professional satisfaction. J. Educ. 2022, 204, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postiglione, G. Education and cultural diversity in multiethnic China. In Minority Education in China: Balancing Unity and Diversity in an Era of Critical Pluralism; Hong Kong University Press: Hong Kong, China, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölscher, S.I.; Gharaei, N.; Schachner, M.K.; Ott, P.K.; Umlauft, S. Do my students think I am racist? Effects on teacher self-efficacy, stress, job satisfaction and supporting students in culturally diverse classrooms. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2024, 138, 104425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peverly, S.T. Moving past cultural homogeneity: Suggestions for comparisons of students’ educational outcomes in the United States and China. Psychol. Sch. 2005, 42, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Feng, D. How culture matters in educational borrowing? Chinese teachers’ dilemmas in a global era. Cogent Educ. 2015, 2, 1046410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Muñoz, M. Teachers’ perceptions of effective teaching: A comparative study of elementary school teachers from China and the USA. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 2016, 28, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Onwuegbuzie, A. Teachers’ motivation for entering the teaching profession and their job satisfaction: A cross-cultural comparison of China and other countries. Learn. Environ. Res. 2014, 17, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cousineau, C.; Wang, B.; Zeng, L.; Sun, A.; Kohrman, E.; Li, N.; Tok, E.; Boswell, M.; Rozelle, S. Exploring teacher job satisfaction in rural China: Prevalence and correlates. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roffey, S. Developing positive relationships in schools. In Positive Relationships: Evidence Based Practice Across the World; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamre, B.K.; Pianta, R.C.; Downer, J.T.; DeCoster, J.; Mashburn, A.J.; Jones, S.M.; Brown, J.L.; Cappella, E.; Atkins, M.; Rivers, S.E.; et al. Teaching through interactions: Testing a developmental framework of teacher effectiveness in over 4,000 classrooms. Elem. Sch. J. 2013, 113, 461–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, C. How relationships impact teacher job satisfaction. Int. J. Mod. Educ. Stud. 2021, 5, 280–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateş, A.; Ünal, A. The relationship between diversity management, job satisfaction and organizational commitment in teachers: A mediating role of perceived organizational support. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2021, 21, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.N.; Wu, J.Y.; Kwok, O.M.; Villarreal, V.; Johnson, A.Y. Indirect effects of child reports of teacher-student relationship on achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 104, 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Zhang, L. Longitudinal associations between teacher-student relationships and prosocial behavior in adolescence: The mediating role of basic need satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Qi, C. The relationship between teacher-student relationship and academic achievement: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2019, 15, em1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd ed.; Sag: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, T.; Haiyan, Q. Leadership and culture in Chinese education. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2000, 20, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, G.; Yang, C.; Glutting, J.; Huang, X.; He, X.; Zhang, W.; Chen, D. Understanding teacher-student relationships, student-student relationships, and conduct problems in China and the United States. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 2, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, H.M. Meeting the needs of all students through differentiated instruction: Helping every child reach and exceed standards. Clear. House J. Educ. Strateg. Issues Ideas 2008, 81, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, R.; Sallie, A.P.; Sanders, C.A. Differentiated instructional strategies to accommodate students with varying needs and learning styles. In Proceedings of the Urban Education Conference, Jackson, MS, USA, 18–20 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Markey, K.; Graham, M.M.; Tuohy, D.; McCarthy, J.; O’Donnell, C.; Hennessy, T.; Fahy, A.; O’Brien, B. Navigating learning and teaching in expanding culturally diverse higher education settings. High. Educ. Pedagog. 2023, 8, 2165527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.L. Multicultural education as a framework for educating English language learners in the United States. Int. J. Multidiscip. Perspect. High. Educ. 2019, 4, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.H. Multicultural education and culturally and linguistically diverse field placements: Influence on pre-service teacher perceptions. J. Spec. Educ. Apprenticesh. 2020, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernest, J.M.; Heckaman, K.A.; Thompson, S.E.; Hull, K.M.; Carter, S.W. Increasing the teaching efficacy of a beginning special education teacher using differentiated instruction: A case study. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 2011, 26, 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- McCarty, W.; Crow, S.R.; Mims, G.A.; Potthoff, D.E.; Harvey, J.S. Renewing teaching practices: Differentiated instruction in the college classroom. J. Curric. Teach. Learn. Leadersh. Educ. 2016, 1, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Cherng, H.Y.S.; Davis, L.A. Multicultural matters: An investigation of key assumptions of multicultural education reform in teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 2019, 70, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, S. Ethnic diversity, national unity and multicultural education in China. US-China Educ. Rev. 2011, 5, 726–739. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.J. Culturally responsive teaching in China: Instructional strategy and teachers’ attitudes. Intercult. Educ. 2016, 27, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. Translanguaging as a social justice strategy: The case of teaching Chinese to ethnic minority students in Hong Kong. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2023, 24, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsen, J.J.; Ewing, D.L.; Kwoka, M. Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion, perceived adequacy of support and classroom learning environment. Learn. Environ. Res. 2014, 17, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, C.; Anderson, J.; Allen, K.A. The importance of teacher attitudes to inclusive education. In Inclusive Education: Global Issues and Controversies; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, M.; Siddiqui, S.; Adil, M.S. Breaking barriers: The influence of teachers’ attitudes on inclusive education for students with mild learning disabilities (MLDs). Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, W.S.E. Examining factors influencing teachers’ intentions in implementing inclusive practices in Hong Kong classrooms. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2024, 24, 376–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaja, K.; Springer, J.T.; Bigatti, S.; Gibau, G.S.; Whitehead, D.; Grove, K. Multicultural teaching: Barriers and recommendations. J. Excell. Coll. Teach. 2010, 21, 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, S.R.; Yough, M.; Finney-Miller, E.A.; Mathew, S.; Haken-Hughes, A.; Ariati, J. Faculty perceptions of teaching diversity: Definitions, benefits, drawbacks, and barriers. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Porter, L.; Harrison, B.J.; Wohlstetter, P. Barriers to increasing teacher diversity: The need to move beyond aspirational legislation. Educ. Urban Soc. 2023, 55, 395–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulsky, J. Barriers to teacher diversity in a predominantly white district. J. Educ. Hum. Resour. 2023, 41, 662–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.A. The emergence of job satisfaction in organizational behavior. J. Manag. Hist. 2006, 12, 262–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietjen, M.A.; Myers, R.M. Motivation and job satisfaction. Manag. Decis. 1998, 36, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Q.; Luo, L. Early childhood teachers’ job satisfaction and turnover intention in China and Singapore: A latent profile analysis. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2023, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, K.E.; Wang, X.; Qi, Y.; Norzan, N. The factors associated with teachers’ job satisfaction and their impacts on students’ achievement: A review (2010–2021). Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, J.; Antoun, S. Impact of job satisfaction on teacher well-being and education quality. Pedagog. Res. 2024, 9, em0204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jiang, H.; Jin, W.; Jiang, J.; Liu, J.; Guan, J.; Liu, Y.; Bin, E. Examining the antecedents of novice STEM teachers’ job satisfaction: The roles of personality traits, perceived social support, and work engagement. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, N.; Stearns, E.; Moller, S.; Mickelson, R.A. Teacher job satisfaction and student achievement: The roles of teacher professional community and teacher collaboration in schools. Am. J. Educ. 2017, 123, 203–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J.D. Teacher Job Satisfaction as Related to Student Performance on State-Mandated Testing. Ph.D. Thesis, Lindenwood University, St Charles, MO, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arifin, H.M. The influence of competence, motivation, and organisational culture to high school teacher job satisfaction and performance. Int. Educ. Stud. 2015, 8, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.M.; Muñoz, M.A. Predictors of new teacher satisfaction in urban schools: Effects of personal characteristics, general job facets, and teacher-specific job facets. J. Sch. Leadersh. 2016, 26, 92–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Zhou, S. The influence of teacher’s job satisfaction on students’ performance: An empirical analysis based on large-scale survey data of Jiangsu province. Sci. Insights Educ. Front. 2020, 6, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fütterer, T.; van Waveren, L.; Hübner, N.; Fischer, C.; Sälzer, C. I can’t get no (job) satisfaction? Differences in teachers’ job satisfaction from a career pathways perspective. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2023, 121, 103942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peršēvica, A. The significance of the teachers’ job satisfaction in the process of assuring quality education. Probl. Educ. 21st Century 2011, 34, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treputtharat, S.; Tayiam, S. School climate affecting job satisfaction of teachers in primary education, Khon Kaen, Thailand. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 116, 996–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Qi, Z. The influence of school climate on teachers’ job satisfaction: The mediating role of teachers’ self-efficacy. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obineli, A.S. Teachers’ perception of the factors affecting job satisfaction in Ekwusigo local government of Anambra State, Nigeria. Afr. Res. Rev. 2013, 7, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohide, A.D.F.; Mbogo, R.W.; Alyaha, D.O.; Mbogo, R.W. Demographic factors affecting teachers’ job satisfaction and performance in private primary schools in Yei Town, South Sudan. IRA-Int. J. Educ. Multidiscip. Stud. 2017, 8, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, S.; Xu, X.; Stronge, J. The influences of teachers’ perceptions of using student achievement data in evaluation and their self-efficacy on job satisfaction: Evidence from China. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2018, 19, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, S.; Kalim, U. Factors influencing teachers’ job satisfaction in the Pakistan’s public school. Int. J. Humanit. Innov. 2021, 4, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhyeli, H.E.; Ewijk, A.V. Prioritisation of factors influencing teachers’ job satisfaction in the UAE. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2018, 12, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, K.; Chen, Z.; Pan, Z. Exploring the contributions of job resources, job demands, and job self-efficacy to STEM teachers’ job satisfaction: A commonality analysis. Psychol. Sch. 2023, 60, 122–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.; Oliveira, C. Teacher and school determinants of teacher job satisfaction: A multilevel analysis. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2020, 31, 641–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melaku, S.M.; Hundii, T.S. Factors Affecting Teachers Job Satisfaction in Case of Wachemo University. Int. J. Psychol. Stud. 2020, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbonea, T.J.; Eric, A.; Ounga, O.; Nyarusanda, C. Factors affecting secondary school teachers’ job satisfaction in Lushoto District, Tanga Region in Tanzania. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2021, 9, 474–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroudi, S.; Tamim, R.; Hojeij, Z. A quantitative investigation of intrinsic and extrinsic factors influencing teachers’ job satisfaction in Lebanon. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2022, 21, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guoba, A.; Žygaitienė, B.; Kepalienė, I. Factors influencing teachers’ job satisfaction. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2022, 4, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Qi, J.; Zhen, R. Impacting factors of middle school teachers’ satisfaction with online training for sustainable professional development under the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ololube, N.P. Professionalism, demographics, and motivation: Predictors of job satisfaction among Nigerian teachers. Int. J. Educ. Policy Leadersh. 2007, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Akomolafe, M.J.; Ogunmakin, A.O. Job satisfaction among secondary school teachers: Emotional intelligence, occupational stress and self-efficacy as predictors. J. Educ. Soc. Res. 2014, 4, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahoor, Z. A comparative study of psychological well-being and job satisfaction among teachers. Indian J. Health Wellbeing 2015, 6, 181–184. [Google Scholar]

- Mehboob, F.; Sarwar, M.A.; Bhutto, N.A. Factors affecting job satisfaction among faculty member. Asian J. Bus. Manag. Sci. 2012, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Nyagaya, P.A. Factors Influencing Teachers’ Level of Job Satisfaction in Public Primary Schools in Kayole Division, Embakasi Sub County, Kenya. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Crisci, A.; Sepe, E.; Malafronte, P. What influences teachers’ job satisfaction and how to improve, develop and reorganize the school activities associated with them. Qual. Quant. 2019, 53, 2403–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hee, O.C.; Shukor, M.F.A.; Ping, L.L.; Kowang, T.O.; Fei, G.C. Factors influencing teacher job satisfaction in Malaysia. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2019, 9, 1166–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toropova, A.; Myrberg, E.; Johansson, S. Teacher job satisfaction: The importance of school working conditions and teacher characteristics. Educ. Rev. 2021, 73, 71–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouëdard, P.; Kools, M.; George, B. The impact of schools as learning organisations on teachers’ self-efficacy and job satisfaction: A cross-country analysis. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2023, 34, 331–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Wang, M.; Zhang, S. School culture and teacher job satisfaction in early childhood education in China: The mediating role of teaching autonomy. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2023, 24, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.S.K.; Heng, T.N. Case study of factors influencing job satisfaction in two Malaysian universities. Int. Bus. Res. 2009, 2, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crehan, L. Exploring the Impact of Career Models on Teacher Motivation; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dinham, S.; Scott, C. A three domain model of teacher and school executive career satisfaction. J. Educ. Adm. 1998, 36, 362–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korb, K.A.; Akintunde, O.O. Exploring factors influencing teacher job satisfaction in Nigerian schools. Niger. J. Teach. Educ. Train. 2013, 11, 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Yuh, J.; Choi, S. Sources of social support, job satisfaction, and quality of life among childcare teachers. Soc. Sci. J. 2017, 54, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholze, A.; Hecker, A. The job demands-resources model as a theoretical lens for the bright and dark side of digitization. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 155, 108177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N.; Wang, H.P. The influence of students’ sense of social connectedness on prosocial behavior in higher education institutions in Guangxi, China: A perspective of perceived teachers’ character teaching behavior and social support. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1029315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.A.; Slaten, C.D.; Arslan, G.; Roffey, S.; Craig, H.; Vella-Brodrick, D.A. School belonging: The importance of student and teacher relationships. In The Palgrave Handbook of Positive Education; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesonen, H.V.; Rytivaara, A.; Palmu, I.; Wallin, A. Teachers’ stories on sense of belonging in co-teaching relationship. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 65, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Winkel, D.; Selvarajan, T.T. Managing diversity at work: Does psychological safety hold the key to racial differences in employee performance? J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2013, 86, 242–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongrey, R.; Rokade, V. Assessing the effect of perceived diversity practices and psychological safety on contextual performance for sustainable workplace. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertürk, R. The effect of teacher autonomy on teachers’ professional dedication. Int. J. Psychol. Educ. Stud. 2023, 10, 494–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, E.E.; Sandilos, L.E.; Ellis, E.; Neugebauer, S.R. Teachers survive together: Teacher collegial relationships and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sch. Psychol. 2023, 39, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. TALIS 2018 Technical Report: Preliminary Version; OECD: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F.; Rice, J. Little Jiffy, mark IV. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1974, 34, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapley, L.S. A value for n-person games. In Contribution to the Theory of Games; The Rand Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Spilt, J.L.; Koomen, H.M.; Thijs, J.T. Teacher wellbeing: The importance of teacher-student relationships. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 23, 457–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrup, K.; Klusmann, U.; Lüdtke, O.; Göllner, R.; Trautwein, U. Student misbehavior and teacher well-being: Testing the mediating role of the teacher-student relationship. Learn. Instr. 2018, 58, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, D.; Shephard, D.; Mendenhall, M. “I always take their problem as mine”–understanding the relationship between teacher-student relationships and teacher well-being in crisis contexts. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2022, 95, 102670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaVergne, D.D.; Larke, A., Jr.; Elbert, C.D.; Jones, W.A. The benefits and barriers toward diversity inclusion regarding agricultural science teachers in Texas secondary agricultural education programs. J. Agric. Educ. 2011, 52, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevarez, C.; Jouganatos, S.; Wood, J.L. Benefits of teacher diversity: Leading for transformative change. J. Sch. Adm. Res. Dev. 2019, 4, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Lee, S.W. Enhancing teacher self-efficacy in multicultural classrooms and school climate: The role of professional development in multicultural education in the United States and South Korea. Aera Open 2020, 6, 2332858420973574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorski, P.C.; Davis, S.N.; Reiter, A. Self-efficacy and multicultural teacher education in the United States: The factors that influence who feels qualified to be a multicultural teacher educator. Multicult. Perspect. 2012, 14, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H. Educating culturally responsive Han teachers: Case study of a teacher education program in China. Int. J. Multicult. Educ. 2018, 20, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demszky, D.; Liu, J.; Hill, H.C.; Jurafsky, D.; Piech, C. Can automated feedback improve teachers’ uptake of student ideas? Evidence from a randomized controlled trial in a large-scale online course. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 2023, 46, 483–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, K.D.G. Diversity in the Digital Age: Integrating Pedagogy and Technology for Equity and Inclusion. Doctoral Dissertation, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.J.; Johnson, L. Building supportive and friendly school environments: Voices from beginning teachers. Child. Educ. 2010, 86, 302–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Rao, N. Teacher professional development among preschool teachers in rural China. J. Early Child. Teach. Educ. 2021, 42, 219–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparisi, D.; Granados, L.; Sanmartin, R.; Martínez-Monteagudo, M.C.; García-Fernández, J.M. Relationship between emotional intelligence, generativity and self-efficacy in secondary school teachers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zhang, N.; Yang, D.; Lin, W.; Maulana, R. From awareness to action: Multicultural attitudes and differentiated instruction of teachers in Chinese teacher education programmes. Learn. Environ. Res. 2024, 28, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Bergin, C.; Olsen, A.A. Positive teacher-student relationships may lead to better teaching. Learn. Instr. 2022, 80, 101581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guijarro-Ojeda, J.R.; Ruiz-Cecilia, R.; Cardoso-Pulido, M.J.; Medina-Sánchez, L. Examining the interplay between queerness and teacher wellbeing: A qualitative study based on foreign language teacher trainers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Declaration | The United States | China | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Percentage | N | Percentage | ||

| Gender | Male | 837 | 32.77% | 1035 | 26.03% |

| Female | 1717 | 67.23% | 2941 | 73.97% | |

| Age | Under 25 | 88 | 3.49% | 119 | 2.99% |

| 25–29 | 281 | 11.13% | 534 | 13.43% | |

| 30–39 | 699 | 27.69% | 1316 | 33.11% | |

| 40–49 | 790 | 31.30% | 1418 | 35.67% | |

| 50–59 | 493 | 19.53% | 566 | 16.29% | |

| 60 and above | 173 | 6.85% | 22 | 3.00% | |

| Highest level of formal education completed | ISCED 2011 Level 3 | 2 | 0.08% | 0 | 0.00% |

| ISCED 2011 Level 5 | 5 | 0.20% | 35 | 0.88% | |

| ISCED 2011 Level 6 | 972 | 38.10% | 3413 | 86.12% | |

| ISCED 2011 Level 7 | 1524 | 59.74% | 514 | 12.97% | |

| ISCED 2011 Level 8 | 48 | 1.88% | 1 | 0.03% | |

| Employment status | Permanent employment (an on-going contract with no fixed end-point before the age of retirement) | 1664 | 65.98% | 1190 | 30.07% |

| Fixed-term contract for a period of more than 1 school year | 272 | 10.79% | 2716 | 68.62% | |

| Fixed-term contract for a period of 1 school year or less | 586 | 23.24% | 52 | 1.31% | |

| Teaching as the first choice as a career | Yes | 1465 | 58.04% | 3417 | 86.48% |

| No | 1059 | 41.96% | 534 | 13.52% | |

| Characteristics | Declaration | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Work experience | Experiences as a teacher at this school | 8.10 | 7.48 | 12.01 | 7.81 |

| Experiences as a teacher in total | 13.99 | 9.41 | 16.80 | 9.65 | |

| Experiences in other education roles, not as a teacher | 3.25 | 6.22 | 0.39 | 2.39 | |

| Experiences in other non-education roles | 6.52 | 7.62 | 0.36 | 1.91 | |

| DPs | T–S Rs | JS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DPs | – | ||

| T–S R | 0.164 *** | – | |

| JS | 0.162 *** | 0.385 *** | – |

| Dependent Variable | Items | Options |

|---|---|---|

| Job satisfaction | * I would like to change to another school if that were possible | 1 = Strongly disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Agree 4 = Strongly agree |

| I enjoy working at this school | ||

| I would recommend this school as a good place to work | ||

| All in all, I am satisfied with my job | ||

| The advantages of being a teacher clearly outweigh the disadvantages | ||

| If I could decide again, I would still choose to work as a teacher | ||

| * I regret that I decided to become a teacher | ||

| * I wonder whether it would have been better to choose another profession | ||

| Determining course content | ||

| Selecting teaching methods | ||

| Assessing students’ learning | ||

| Disciplining students | ||

| Determining the amount of homework to be assigned | ||

| Independent variable | Items | Options |

| Diversity practices | Supporting activities or organisations that encourage students’ expression of diverse ethnic and cultural identities (e.g., artistic groups) | 1 = Yes 2 = No |

| Organising multicultural events (e.g., cultural diversity day) | ||

| Teaching students how to deal with ethnic and cultural discrimination | ||

| Adopting teaching and learning practices that integrate global issues throughout the curriculum | ||

| Control variables | Items | |

| Highest level of formal education | 1 = Below ISCED 2011 Level 3 2 = ISCED 2011 Level 3 3 = ISCED 2011 Level 4 4 = ISCED 2011 Level 5 5 = ISCED 2011 Level 6 6 = ISCED 2011 Level 7 7 = ISCED 2011 Level 8 | |

| Teaching as the first choice as a career | 1 = Yes 2 = No | |

| Employment status | 1 = Permanent employment (an on-going contract with no fixed end-point before the age of retirement) 2 = Fixed-term contract for a period of more than 1 school year 3 = Fixed-term contract for a period of 1 school year or less | |

| Number of enrolled students | 1 = Under 250 2 = 250–499 3 = 500–749 4 = 750–999 5 = 1000 and above | |

| Percentage of students with special needs | 1 = None 2 = 1–10% 3 = 11–30% 4 = 31% to 60% 5 = More than 60% | |

| Percentage of the school’s students from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds | 1 = None 2 = 1–10% 3 = 11–30% 4 = 31% to 60% 5 = More than 60% | |

| Control variables | Mean | SD |

| Total hours spent on tasks related to job at school | 45.90 | 15.41 |

| Mediating variable | Items | Options |

| Teaching–Student relations | Teachers and students usually get on well with each other | 1 = Strongly disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Agree 4 = Strongly agree |

| Most teachers believe that the students’ well-being is important | ||

| Most teachers are interested in what students have to say | ||

| If a student needs extra assistance, the school provides it | ||

| Dependent Variable: Teachers’ Job Satisfaction | The United States | China | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | S.E. | t | p | β | S.E. | t | p | |

| Diversity practices | 0.263 | 0.027 | 9.89 | <0.001 | 0.135 | 0.032 | 4.29 | <0.001 |

| Highest level of formal education | −0.256 | 0.105 | −2.45 | 0.015 | 0.073 | 0.159 | 0.46 | 0.646 |

| Teaching as the first choice as a career | −0.450 | 0.110 | −4.08 | <0.001 | −1.599 | 0.168 | −9.53 | <0.001 |

| Employment status | 0.036 | 0.066 | 0.55 | 0.581 | −0.163 | 0.136 | −1.20 | 0.231 |

| Total hours spent on tasks related to job at school | 0.103 | 0.092 | 1.12 | 0.264 | 0.058 | 0.126 | 0.46 | 0.647 |

| Number of enrolled students at the school | −0.004 | 0.004 | −1.18 | 0.236 | −0.007 | 0.005 | −1.30 | 0.193 |

| Count of special needs students | −0.235 | 0.159 | −1.48 | 0.139 | −0.451 | 0.114 | −3.94 | <0.001 |

| The percentage of students from socio-economically disadvantaged homes | −0.171 | 0.048 | −3.52 | <0.001 | −0.202 | 0.070 | −2.89 | 0.004 |

| Constant | 11.587 | 0.854 | 13.57 | <0.001 | 14.469 | 1.152 | 12.56 | <0.001 |

| N | 1784 | 896 | ||||||

| R2 | 0.080 | 0.173 | ||||||

| Factor | The United States | China | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shapley Value | Percent | Shapley Value | Percent | |

| Diversity practices | 0.054 | 67.13% | 0.024 | 13.84% |

| Highest level of formal education | 0.002 | 2.68% | 0.002 | 0.91% |

| Teaching as the first choice as a career | 0.009 | 10.93% | 0.095 | 54.85% |

| Employment status | 0.000 | 0.41% | 0.001 | 0.63% |

| Total hours spent on tasks related to job at school | 0.001 | 0.74% | 0.001 | 0.54% |

| Number of enrolled students at the school | 0.001 | 1.45% | 0.001 | 0.56% |

| Count of special needs students | 0.001 | 1.71% | 0.019 | 10.75% |

| The percentage of students from socio-economically disadvantaged homes | 0.009 | 11.17% | 0.013 | 7.61% |

| Dependent Variable: Teachers’ Job Satisfaction | The United States | China | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male Middle School Teachers | Female Middle School Teachers | Male Middle School Teachers | Female Middle School Teachers | |||||||||||||

| β | S.E. | t | p | β | S.E. | t | p | β | S.E. | t | p | β | S.E. | t | p | |

| Diversity practices | 0.295 | 0.045 | 6.56 | <0.001 | 0.241 | 0.033 | 7.22 | <0.001 | 0.129 | 0.067 | 1.94 | 0.054 | 0.136 | 0.036 | 3.80 | <0.001 |

| Highest level of formal education | −0.352 | 0.183 | −1.92 | 0.055 | −0.206 | 0.128 | −1.61 | 0.107 | −0.091 | 0.417 | −0.22 | 0.828 | 0.166 | 0.170 | 0.97 | 0.330 |

| Teaching as the first choice as a career | −0.273 | 0.184 | −1.49 | 0.137 | −0.560 | 0.139 | −4.02 | <0.001 | −1.496 | 0.323 | −4.62 | <0.001 | −1.683 | 0.196 | −8.58 | <0.001 |

| Employment status | 0.039 | 0.114 | 0.35 | 0.730 | 0.037 | 0.082 | 0.46 | 0.646 | −0.790 | 0.304 | −2.60 | 0.010 | 0.023 | 0.151 | 0.15 | 0.881 |

| Total hours spent on tasks related to job at school | 0.005 | 0.139 | 0.04 | 0.971 | 0.183 | 0.124 | 1.48 | 0.140 | 0.259 | 0.234 | 1.10 | 0.270 | −0.004 | 0.151 | −0.02 | 0.981 |

| Number of enrolled students at the school | −0.008 | 0.006 | −1.25 | 0.213 | −0.002 | 0.005 | −0.50 | 0.620 | −0.007 | 0.013 | −0.54 | 0.591 | −0.007 | 0.006 | −1.22 | 0.224 |

| Count of special needs students | −0.245 | 0.243 | −1.01 | 0.315 | −0.252 | 0.210 | −1.20 | 0.230 | −0.570 | 0.245 | −2.33 | 0.021 | −0.383 | 0.129 | −2.97 | 0.003 |

| The percentage of students from socio-economically disadvantaged homes | −0.142 | 0.083 | −1.71 | 0.088 | −0.186 | 0.060 | −3.11 | 0.002 | −0.310 | 0.152 | −2.04 | 0.043 | −0.167 | 0.078 | −2.14 | 0.032 |

| Constant | 11.880 | 1.433 | 8.29 | <0.001 | 11.410 | 1.075 | 10.61 | <0.001 | 17.161 | 2.508 | 6.84 | <0.001 | 13.469 | 1.309 | 10.29 | <0.001 |

| N | 606 | 1176 | 241 | 655 | ||||||||||||

| R2 | 0.089 | 0.077 | 0.218 | 0.173 | ||||||||||||

| Age | Dependent Variable: Teachers’ Job Satisfaction | The United States | China | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | S.E. | t | p | β | S.E. | t | p | ||

| Under 30 | Diversity practices | 0.255 | 0.025 | 10.34 | <0.001 | 0.187 | 0.029 | 6.39 | <0.001 |

| Highest level of formal education | −0.252 | 0.095 | −2.64 | 0.008 | 0.211 | 0.135 | 1.56 | 0.118 | |

| Teaching as the first choice as a career | −0.488 | 0.103 | −4.74 | <0.001 | −1.204 | 0.146 | −8.27 | <0.001 | |

| Employment status | 0.014 | 0.062 | 0.22 | 0.825 | −0.082 | 0.093 | −0.88 | 0.380 | |

| Total hours spent on tasks related to job at school | 0.082 | 0.087 | 0.94 | 0.348 | 0.243 | 0.116 | 2.09 | 0.037 | |

| Number of enrolled students at the school | −0.199 | 0.106 | −1.87 | 0.061 | −0.209 | 0.139 | −1.50 | 0.133 | |

| Count of special needs students | −0.312 | 0.136 | −2.30 | 0.021 | −0.382 | 0.114 | −3.36 | <0.001 | |

| The percentage of students from socio-economically disadvantaged homes | −0.178 | 0.044 | −4.03 | <0.001 | −0.161 | 0.056 | −2.87 | 0.004 | |

| Constant | 12.903 | 0.837 | 15.41 | <0.001 | 11.457 | 1.024 | 11.19 | <0.001 | |

| N | 1983 | 1146 | |||||||

| R2 | 0.082 | 0.133 | |||||||

| 30–49 | Diversity practices | 0.240 | 0.021 | 11.18 | <0.001 | 0.229 | 0.022 | 10.54 | <0.001 |

| Highest level of formal education | −0.031 | 0.082 | −0.38 | 0.706 | −0.058 | 0.082 | −0.70 | 0.484 | |

| Teaching as the first choice as a career | −0.558 | 0.092 | −6.07 | <0.001 | −0.628 | 0.094 | −6.70 | <0.001 | |

| Employment status | 0.021 | 0.057 | 0.37 | 0.715 | 0.085 | 0.061 | 1.39 | 0.165 | |

| Total hours spent on tasks related to job at school | 0.082 | 0.077 | 1.07 | 0.284 | 0.072 | 0.078 | 0.92 | 0.359 | |

| Number of enrolled students at the school | −0.272 | 0.094 | −2.90 | 0.004 | −0.255 | 0.094 | −2.71 | 0.007 | |

| Count of special needs students | −0.295 | 0.106 | −2.79 | 0.005 | −0.330 | 0.102 | −3.22 | <0.001 | |

| The percentage of students from socio-economically disadvantaged homes | −0.130 | 0.039 | −3.36 | <0.001 | −0.126 | 0.039 | −3.19 | <0.001 | |

| Constant | 11.866 | 0.700 | 16.95 | <0.001 | 12.182 | 0.707 | 17.24 | <0.001 | |

| N | 2527 | 2430 | |||||||

| R2 | 0.078 | 0.081 | |||||||

| 50 and above | Diversity practices | 0.264 | 0.026 | 10.07 | <0.001 | 0.133 | 0.032 | 4.18 | <0.001 |

| Highest level of formal education | −0.223 | 0.103 | −2.17 | 0.030 | 0.199 | 0.157 | 1.27 | 0.205 | |

| Teaching as the first choice as a career | −0.418 | 0.109 | −3.85 | <0.001 | −1.647 | 0.169 | −9.77 | <0.001 | |

| Employment status | 0.007 | 0.065 | 0.12 | 0.908 | 0.037 | 0.126 | 0.29 | 0.771 | |

| Total hours spent on tasks related to job at school | 0.070 | 0.091 | 0.77 | 0.441 | 0.100 | 0.126 | 0.79 | 0.428 | |

| Number of enrolled students at the school | −0.227 | 0.113 | −2.00 | 0.045 | −0.171 | 0.154 | −1.11 | 0.265 | |

| Count of special needs students | −0.252 | 0.157 | −1.60 | 0.109 | −0.462 | 0.115 | −4.02 | <0.001 | |

| The percentage of students from socio-economically disadvantaged homes | −0.169 | 0.048 | −3.54 | <0.001 | −0.200 | 0.070 | −2.84 | 0.005 | |

| Constant | 12.533 | 0.906 | 13.84 | <0.001 | 12.961 | 1.159 | 11.18 | <0.001 | |

| N | 1807 | 896 | |||||||

| R2 | 0.077 | 0.159 | |||||||

| Dependent Variable: Teachers’ Job Satisfaction | The United States | China | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robustness Test 1: Remove Some Control Variables | β | S.E. | t | p | β | S.E. | t | p |

| Diversity practices | 0.257 | 0.024 | 10.62 | <0.001 | 0.142 | 0.029 | 4.97 | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.099 | 0.043 | 2.32 | 0.020 | −0.259 | 0.059 | −4.41 | <0.001 |

| Highest level of formal education | −0.211 | 0.095 | −2.22 | 0.026 | 0.137 | 0.148 | 0.93 | 0.352 |

| Teaching as the first choice as a career | −0.439 | 0.101 | −4.36 | <0.001 | −1.666 | 0.152 | −10.93 | <0.001 |

| Employment status | 0.059 | 0.060 | 0.97 | 0.331 | −0.137 | 0.124 | −1.10 | 0.269 |

| Total hours spent on tasks related to job at school | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.91 | 0.365 | −0.003 | 0.004 | −0.94 | 0.349 |

| Constant | 10.472 | 0.643 | 16.27 | <0.001 | 13.124 | 0.931 | 14.10 | <0.001 |

| N | 2185 | 1084 | ||||||

| R² | 0.063 | 0.149 | ||||||

| Robustness test 2: Replace the dependent variable | β | S.E. | t | p | β | S.E. | t | p |

| Diversity practices | 0.015 | 0.002 | 9.13 | <0.001 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 3.77 | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.008 | 0.003 | 2.78 | 0.005 | −0.018 | 0.004 | −4.28 | <0.001 |

| Highest level of formal education | −0.007 | 0.007 | −1.05 | 0.295 | −0.000 | 0.011 | −0.02 | 0.986 |

| Teaching as the first choice as a career | −0.027 | 0.007 | −3.84 | <0.001 | −0.087 | 0.011 | −7.84 | <0.001 |

| Employment status | 0.004 | 0.004 | 1.00 | 0.317 | −0.001 | 0.009 | −0.13 | 0.895 |

| Total hours spent on tasks related to job at school | 0.007 | 0.006 | 1.17 | 0.242 | 0.012 | 0.008 | 1.42 | 0.157 |

| Number of enrolled students at the school | −0.009 | 0.007 | −1.27 | 0.203 | −0.002 | 0.010 | −0.17 | 0.865 |

| Count of special needs students | −0.024 | 0.010 | −2.41 | 0.016 | −0.037 | 0.008 | −4.83 | <0.001 |

| The percentage of students from socio-economically disadvantaged homes | −0.014 | 0.003 | −4.53 | <0.001 | −0.013 | 0.005 | −2.79 | 0.005 |

| Constant | 3.701 | 0.059 | 63.17 | <0.001 | 3.826 | 0.083 | 46.19 | <0.001 |

| N | 1756 | 892 | ||||||

| R² | 0.082 | 0.161 | ||||||

| The United States | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Causal Relationship | β | S.E. | C.R. | p | ||

| Job Satisfaction | <--- | Diversity Practices | 0.517 | 0.079 | 6.559 | *** |

| Teacher–Student Relationships | <--- | Diversity Practices | 0.188 | 0.036 | 5.163 | *** |

| Job Satisfaction | <--- | Teacher–Student Relationships | 0.666 | 0.084 | 7.908 | *** |

| China | ||||||

| Causal Relationship | β | S.E. | C.R. | p | ||

| Job Satisfaction | <--- | Diversity Practices | 0.241 | 0.083 | 2.909 | *** |

| Teacher–Student Relationships | <--- | Diversity Practices | 0.385 | 0.056 | 6.821 | *** |

| Job Satisfaction | <--- | Teacher–Student Relationships | 0.711 | 0.052 | 13.612 | *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, Y.; Zheng, L. Building Sustainable Teaching Careers: The Impact of Diversity Practices on Middle School Teachers’ Job Satisfaction in China and the United States. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4923. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114923

Xiao Y, Zheng L. Building Sustainable Teaching Careers: The Impact of Diversity Practices on Middle School Teachers’ Job Satisfaction in China and the United States. Sustainability. 2025; 17(11):4923. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114923

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Yu, and Li Zheng. 2025. "Building Sustainable Teaching Careers: The Impact of Diversity Practices on Middle School Teachers’ Job Satisfaction in China and the United States" Sustainability 17, no. 11: 4923. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114923

APA StyleXiao, Y., & Zheng, L. (2025). Building Sustainable Teaching Careers: The Impact of Diversity Practices on Middle School Teachers’ Job Satisfaction in China and the United States. Sustainability, 17(11), 4923. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114923