1. Introduction

Digital technologies have reshaped public governance by enhancing the efficiency of service delivery and enabling new forms of citizen participation. However, these benefits are not experienced equally. The digital divide—rooted in disparities in infrastructure, access to devices, and digital literacy—limits the ability of certain groups to use information and communication technologies (ICTs) effectively [

1,

2,

3,

4]. These barriers disproportionately affect marginalized communities, constraining their access to essential public services and participation in digital society [

5].

Smart governance initiatives increasingly incorporate e-government applications to improve service delivery, transparency, and citizen engagement [

6]. However, despite their transformative potential, these tools may inadvertently reinforce existing inequalities if underlying access and skills gaps remain unaddressed [

7,

8,

9]. While developed countries often prioritize technological innovation, developing economies frequently face infrastructural constraints, limited digital literacy, and institutional weaknesses that hinder inclusive digital governance [

4]. These challenges highlight the need to evaluate how digital governance tools function in practice, particularly in socially and spatially unequal urban settings.

The concept of the “digital divide” first emerged in policy debates and later gained prominence in academic research during the early 1990s [

10]. Over time, scholars have conceptualized the digital divide across three interrelated levels. The first-level digital divide focuses on access to ICTs, emphasizing disparities shaped by socio-economic status, geography, and infrastructure [

1,

11]. As internet access expanded, attention shifted to the second-level divide, which concerns inequalities in digital literacy and skills that limit effective technology use [

12,

13]. More recently, a third-level digital divide has been identified, referring to the unequal outcomes of digital engagement. Research shows that individuals with higher digital competence tend to gain greater socio-economic, educational, and civic benefits—thereby reinforcing existing inequalities [

1,

13,

14].

Building on this framework, this study investigates how digital inequalities influence citizen participation in urban governance, with a focus on disparities in ICT access, digital literacy, and the use of municipal digital services. Using a three-step quantitative research design, it analyzes how socio-economic factors shape engagement with digital platforms provided by local authorities. Specifically, the study asks the following: How do different dimensions of the digital divide affect citizen engagement in digital public services and participatory urban governance in Istanbul? While the digital divide has been widely explored in national and global contexts, its impact on local-level participation—especially in rapidly urbanizing cities—remains underexamined [

8,

15,

16].

Istanbul presents a compelling case. Despite having advanced digital infrastructure, the city exhibits pronounced socio-economic and spatial disparities that influence digital inclusion and civic engagement. To explore this relationship, the study applies a structured methodology combining logistic regression and thematic analysis using secondary data from the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality. Although Istanbul is Turkey’s most digitally connected city, deep divides persist in who can access and use digital public services. These inequalities make Istanbul a relevant case for examining the dynamics of digital exclusion in urban governance. The 2019 local elections marked a shift in the city’s political landscape, as newly elected opposition-led municipalities began to emphasize transparency, inclusivity, and participatory decision-making—particularly through digital tools.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the literature on the digital divide and its implications for participatory governance.

Section 3 describes the methodological approach, including the three-stage research design, data sources, and analytical methods.

Section 4 presents the main findings, focusing on how digital inequalities influence citizen engagement with public services. Finally,

Section 5 discusses the broader implications of these findings for sustainable urban governance.

2. The Digital Divide and Its Impact on Participatory Governance: A Review of the Literature

Research on the digitalization of urban governance has generally emphasized three interrelated dimensions: disparities in access to technology, the integration of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in public administration, and the exclusionary effects of digital inequality on vulnerable populations. These dimensions are not only technological but deeply socio-political, as limited access to digital infrastructure and low digital literacy constrain individuals’ capacities to engage with digital public services, thereby reinforcing existing socio-economic inequalities and undermining inclusive governance goals. Importantly, the digital divide encompasses not only disparities in internet or device access, but also differences in individuals’ abilities to meaningfully use e-government services [

1,

12,

17,

18]. Empirical studies consistently show that low-income individuals, older adults, migrants, and those with limited educational attainment face the most significant barriers to accessing and using digital platforms for public services [

19,

20]. Although smart governance initiatives aim to foster inclusivity through digital innovation, recent scholarship warns that these tools may inadvertently reproduce or even exacerbate socio-economic exclusion if persistent inequalities in access and skills are not adequately addressed [

21].

The integration of information and communication technologies (ICTs) into governance systems has been a central theme in e-government and smart city research particularly in discussions of data-driven and smart sustainable city frameworks [

22]. These studies commonly conceptualize ICTs as instruments for improving decision-making, enhancing service delivery, increasing transparency, and fostering more participatory and responsive governance [

23,

24,

25]. Research on e-government applications has examined how digital technologies reshape interactions between governments and citizens and transform the efficiency, accessibility, and accountability of public services [

26,

27]. However, despite their transformative potential, significant inequalities persist in digital governance participation—primarily due to structural barriers in physical access and digital literacy [

8,

28]. These disparities present an ongoing challenge for ensuring that smart governance frameworks support equitable and sustainable urban futures.

Digital literacy, in this context, extends beyond mere access to digital tools and Internet connectivity to include the ability to use them effectively and meaningfully. Van Dijk (2005) [

29] defines three core competencies of digital literacy: (i) operational skills (the technical ability to operate digital devices), (ii) information skills (the ability to locate, assess, and interpret online content), and (iii) strategic skills (the capacity to use digital technologies to achieve personal, professional, or civic goals). Of these, operational skills are most frequently measured in empirical research due to their ease of assessment [

30]. However, access to and development of these competencies vary substantially across socio-economic groups, with disadvantaged populations consistently exhibiting lower levels of digital competence and engagement.

Numerous studies have examined the relationship between socio-demographic factors and the digital divide, showing that variables such as gender, age, education, and geographic location significantly shape both access to digital technologies and participation in e-government services. Women and older adults, in particular, face greater structural barriers to using digital platforms compared with men and younger individuals [

19,

31]. Individuals with higher educational attainment and income levels tend to possess stronger digital skills, enabling more effective engagement with digital services, while lower-income and less-educated groups often lack the necessary digital resources or competencies [

16,

30]. Geographic location further exacerbates these disparities, as rural areas and disadvantaged urban districts typically experience more limited digital access and reduced participation rates [

32,

33,

34,

35].

Despite a growing body of research on the digital divide and governance, studies focusing specifically on local-level engagement with digital public services remain limited. Much of the literature continues to emphasize national policy frameworks, large-scale smart governance initiatives, or broad patterns of digital inequality [

15,

16]. While existing research has highlighted how the digital divide affects different socio-economic groups, fewer studies have investigated its implications for municipal-level governance—particularly in rapidly urbanizing contexts, where intra-urban disparities in access and participation tend to be most pronounced [

36].

In Turkey, the majority of existing research has focused on digital disparities across regions, gender, and the rural–urban divide. Studies consistently highlight uneven access to internet infrastructure, ICT tools, and digital literacy—particularly in rural and eastern provinces [

37,

38]. Women, low-income individuals, and those with limited education are especially disadvantaged in terms of both access and digital skills [

39,

40]. The COVID-19 pandemic further exposed these inequalities [

36], particularly in the education sector, where remote learning intensified existing structural barriers for under-resourced communities [

38]. Although these studies have advanced our understanding of digital exclusion, relatively little research has explored its impact on civic engagement and participation—particularly in relation to municipal-level governance.

Although Istanbul is Turkey’s most digitally connected city, recent studies reveal ongoing intra-urban disparities in digital skills and civic engagement [

37,

41]. While some scholarship has addressed e-participation tools and practices [

42,

43], few studies have systematically examined how digital inequalities influence local-level citizen participation in governance. Moreover, the sustainability implications of digital inequality—particularly in rapidly urbanizing cities—remain underexplored. Ensuring inclusive digital participation is essential not only for democratic engagement but also for achieving the long-term goals of sustainable urban governance. This study seeks to address that gap by analyzing how socio-economic and spatial dimensions of the digital divide shape citizen engagement with digital public services in Istanbul. In doing so, it contributes a localized perspective to broader debates on digital exclusion and participatory urban governance, while also highlighting the importance of equitable digital access as a foundation for sustainable development. Istanbul’s ongoing municipal reforms since 2019—centered on transparency, accountability, and citizen involvement—present an important opportunity to evaluate how local digital governance can align with global sustainable development principles. Thus, the case of Istanbul offers valuable insights into the challenges and possibilities of advancing sustainability-oriented digital inclusion in complex urban environments.

3. Materials and Methods

This study employs a structured, three-step quantitative research design to examine how digital inequalities shape citizen engagement with digital public services in Istanbul—a city that presents a unique setting for analyzing intra-urban disparities and their implications for sustainable urban governance. The central research question guiding this analysis is as follows: To what extent do different dimensions of the digital divide influence citizen participation in digital public services and participatory urban governance? To answer this, the methodology is organized into three analytical steps:

- (1)

Identifying key determinants of digital engagement: This first step uses correlation and logistic regression analyses to examine how socio-demographic characteristics, levels of digital literacy, and access to digital tools influence the likelihood of engaging with digital public services. These determinants are interpreted not only as individual-level factors but also as indicators of broader systemic inequalities that hinder inclusive and sustainable governance.

- (2)

Examining patterns of engagement with local digital services: The second step involves the thematic coding of open-ended survey responses to distinguish between different forms of digital interaction. These are classified into two categories: passive engagement (e.g., using digital platforms for information access) and active engagement (e.g., submitting feedback, participating in local decision-making processes). This typology helps evaluate how effectively municipal platforms support participatory urban governance.

- (3)

Analyzing the spatial distribution of digital and civic participation: The third step overlays usage and awareness indicators with socio-economic data at the district level, allowing for spatial analysis of digital inclusion. This enables a geographic assessment of digital inequalities and their impact on equitable participation.

To investigate these relationships, the study utilizes secondary data from the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality (IMM) Open Data Portal, specifically the Digital Divide Map Dataset. The dataset is based on a 2021 survey that included 6224 respondents aged between 18 and 91, covering 806 neighborhoods—approximately 90% of all neighborhoods in Istanbul. Data were collected through a combination of face-to-face interviews and telephone surveys. The dataset provides comprehensive information on digital infrastructure, levels of digital literacy, and patterns of e-government service usage across the city. The data are aggregated at the district level, enabling spatial comparisons across socio-economic contexts. A stratified random sampling method was employed, using neighborhood-level socio-economic status (SES) and population size to determine proportional representation across Istanbul’s 39 districts. Respondents were randomly selected according to district population, gender, and age group. This approach aimed to reflect intra-urban disparities while maintaining statistical validity. The overall sample provides a 95% confidence level for representativeness. Although some responses contain missing values, these were retained in the dataset and excluded only from specific statistical calculations. By integrating both individual-level and spatial analyses, the study aims to provide a more nuanced understanding of how digital inequalities shape participatory governance in Istanbul.

3.1. Determinants of Digital Engagement: Correlation and Logistic Regression Analysis

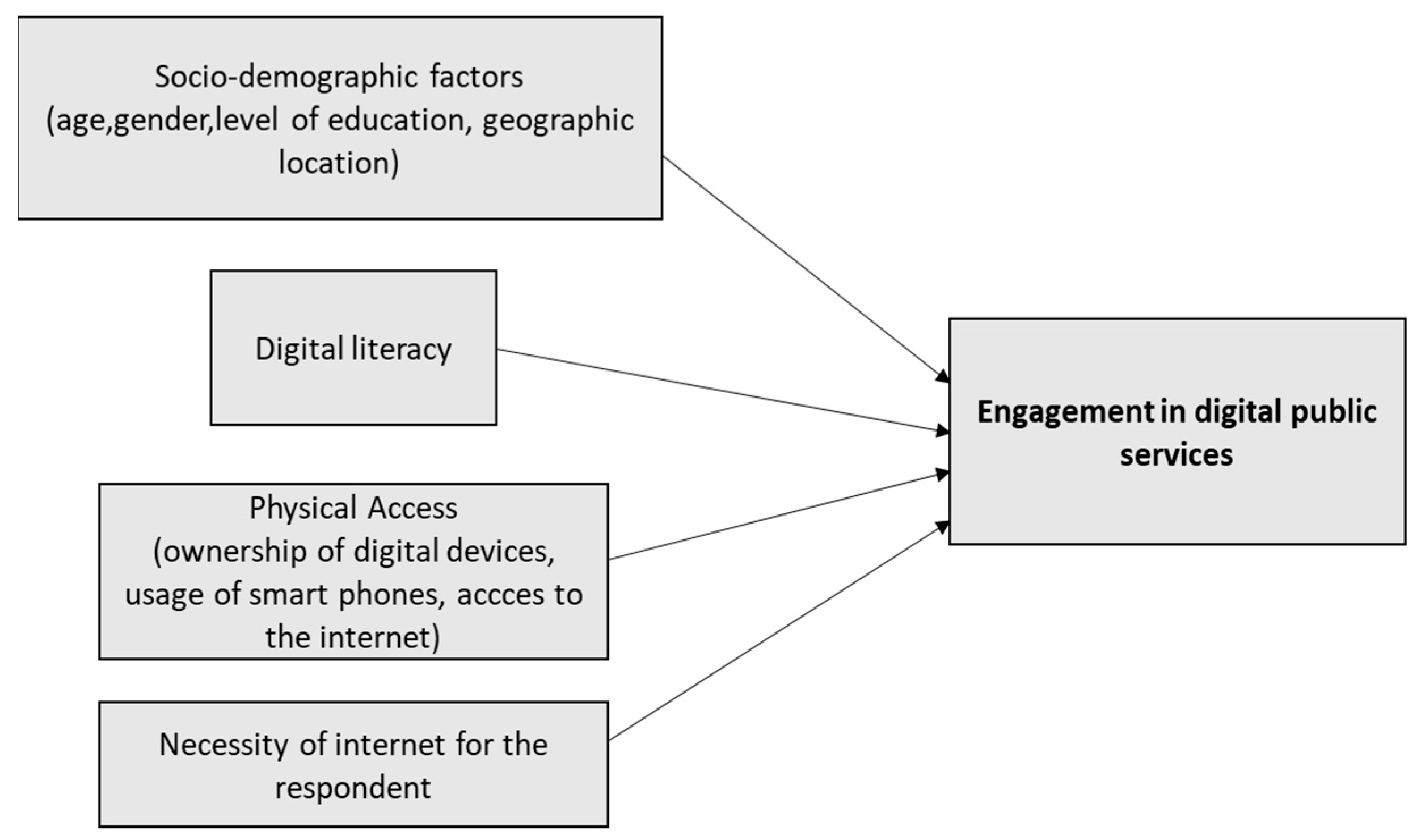

Digital participation is influenced not only by access to the internet but also by an individual’s skills, available resources, and motivation to engage with digital public services. To assess these dimensions, the study focuses on four key factors: socio-demographic characteristics, digital literacy, physical access to digital technologies, and the perceived necessity of the internet. Although these relationships are well established in prior studies, this section emphasizes how they are operationalized and tested through the chosen analytical methods.

To systematically evaluate these relationships, binary logistic regression analysis was selected as the appropriate statistical approach. This method estimates the probability of digital public service engagement based on multiple independent variables. It is particularly suitable for binary outcome variables and large samples, such as the 6224 observations in this study.

The independent variables (

Table 1) encompass four dimensions of the digital divide: (i) Socio-demographic characteristics, including age, gender, education level, and geographic location (measured by district-level socio-economic status); (ii) digital literacy, assessed through indicators of operational, informational, and strategic competencies following Van Dijk’s (2005) framework [

29]; (iii) physical access to digital tools, based on ownership of devices such as computers and smartphones and household Internet connectivity; and (iv) the perceived necessity of the internet, reflecting respondents’ views on its importance in daily life.

Responses to relevant items were measured using a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Composite scores for digital literacy and perceived necessity were computed and categorized into five levels: Very low (1.00–1.799), low (1.80–2.599), acceptable (2.60–3.399), high (3.40–4.199), and very high (4.20–5.00). Categorical variables were converted into dummy variables to facilitate regression analysis.

The study evaluates four dimensions of digital public service engagement, each represented as a binary variable (0 = no, 1 = yes): (1) Use of e-government services, (2) awareness of IMM mobile applications, (3) use of IMM mobile applications, and (4) following IMM activities on social media. Each dependent variable (

Table 1) is analyzed separately to identify distinct factors influencing specific engagement types. Given the binary nature of the outcomes, logistic regression is the appropriate analytical method.

Building on this framework, the following hypotheses are tested:

H1: Gender significantly influences digital public service engagement, with women expected to face greater barriers than men.

H2: Higher educational attainment is positively associated with increased engagement.

H3: Younger individuals are more likely to engage in digital public services.

H4: Residents of higher-income districts are more likely to engage than those in lower-income districts.

H5: Higher digital literacy levels predict greater engagement with digital public services.

H6: Individuals with greater physical access to digital devices and Internet connectivity are more likely to engage.

H7: A stronger perception of the internet’s necessity is positively associated with engagement.

A binary logistic regression model was applied to estimate the probability of citizen engagement with digital public services, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The model predicts the likelihood of engagement (

π) based on a set of independent variables representing socio-demographic characteristics, digital literacy, access to digital technologies, and perceived necessity of the Internet. The general form of the logistic regression equation is as follows:

where π represents the probability of engaging in digital public services.

3.2. Patterns of Engagement: Thematic and Spatial Analysis

The Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality (IMM) provides a centralized platform through both the Google Play Store and Apple App Store, offering access to a wide range of applications related to municipal services. These apps range from real-time public transport updates and cultural event listings to citizen feedback tools and participatory governance platforms.

In the second phase of the study, citizen interaction with these digital platforms was examined by analyzing usage patterns and types of engagement, particularly in relation to applications designed to support public participation. A thematic analysis was conducted using responses to open-ended survey questions from the IMM Digital Divide Mapping Research Survey. Based on this analysis, responses were categorized into two engagement modes: passive and active.

Passive engagement refers to information-seeking behavior, where users access digital platforms to receive municipal service information without direct interaction. Examples include apps such as İBB Şehir Tiyatroları (for theater schedules), İBB Wi-Fi (for accessing free public internet), MobİETT (for real-time bus schedules), and İBB CepTrafik (for traffic updates). These applications primarily support information delivery rather than participatory interaction.

Active engagement, by contrast, involves direct citizen participation in municipal processes, such as submitting feedback, filing service requests, or contributing to decision-making. Applications that support this mode of engagement include Beyaz Masa (for complaints and inquiries), İmar Sorgulama (for zoning-related queries), and İstanbul Senin, which allows users to vote on local planning initiatives and participate in surveys.

Distinguishing between passive and active engagement provides a more nuanced understanding of the role that digital tools play in supporting not just service access but also participatory governance. While passive tools expand access to information, active platforms demonstrate the transformative potential of digital technologies in fostering inclusive civic participation. This distinction is particularly important in the context of sustainable urban governance, where meaningful public involvement is critical to equitable and accountable decision-making.

To complement this thematic analysis, a spatial analysis was conducted to explore geographic variations in digital public service engagement across Istanbul’s districts. Due to the limitations of neighborhood-level data in the IMM dataset, district-level aggregation was used to examine spatial patterns.

District-level averages were calculated for four indicators: (i) usage of e-government services, (ii) awareness of IMM mobile applications, (iii) use of IMM mobile applications, and (iv) following IMM’s social media activities. Additionally, app usage was mapped across districts, distinguishing between those that support passive engagement (e.g., transport or facility services) and those designed for active participation (e.g., citizen feedback and decision-making tools).

Finally, to contextualize these patterns, spatial engagement data were overlaid with the 2022 Socio-Economic Development Index (SEDI), developed by the Turkish Ministry of Industry and Technology. The SEDI offers district-level scores based on indicators such as education, employment, health, infrastructure, innovation, and overall quality of life, enabling a comparative analysis of digital participation in relation to socio-economic development.

4. Findings of the Analysis

The survey results offer key insights into respondents’ demographic characteristics, levels of digital literacy, and access to digital technologies (

Table 2).

The average age of respondents is 44, reflecting broad representation across age groups, with 50% falling between the ages of 25 and 44. In terms of education, the largest share (32.3%) had completed high school, followed by those holding higher education degrees. When evaluated by district-level socio-economic status, 95.5% of respondents lived in areas classified as above average, while only 4.5% resided in districts with below-average socio-economic conditions.

The data show that 61.4% of respondents exhibit high or very high levels of digital literacy, based on their responses to key indicators used to calculate the digital literacy index. Regarding digital access, 91.9% reported having ICT tools in their household, and 93.6% owned a smartphone. Furthermore, 68% indicated that they had internet access and made regular use of it at home.

4.1. Key Determinants of Digital Engagement in Public Services

To identify the key determinants of digital engagement in public services, a Pearson correlation analysis was conducted (

Table 3). The analysis revealed that all bivariate relationships among the core variables were statistically significant at the

p < 0.001 level, with the exception of the correlation between age and geographic location (as measured by the socio-economic status of the respondent’s neighborhood), which was not statistically significant.

The strongest positive correlation was found between digital literacy and the perceived necessity of the internet (coef. = 0.77, p < 0.001). This indicates a strong association between individuals’ digital competence and their perception of the internet as an essential component of daily life.

Age was negatively correlated with digital literacy (coef. = −0.65, p < 0.001), level of education (coef. = −0.51, p < 0.001), and perceived necessity of the internet (coef. = −0.56, p < 0.001). These results suggest that older individuals are generally less digitally literate, have lower educational attainment, and perceive the internet as less essential. In contrast, education was positively correlated with both digital literacy (coef. = 0.65, p < 0.001) and the perceived necessity of the internet (coef. = 0.64, p < 0.001).

These findings support the hypothesis that higher educational attainment is strongly linked to greater digital proficiency and a stronger perception of the internet’s necessity. Taken together, the results underscore the interconnectedness of education, age, and digital engagement capacity, emphasizing the need to address socio-demographic inequalities in the pursuit of inclusive and sustainable digital governance.

Following the correlation analysis, binary logistic regression was used to examine how key independent variables—including socio-demographic characteristics, geographical location, digital literacy, physical access to digital technologies, and perceived internet necessity—affect digital public service engagement (

Table 4). Separate regression models were developed for each of the four dependent variables: usage of e-government services, awareness of Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality (IMM) mobile applications, use of IMM mobile applications, and following the municipality’s activities on social media.

The results indicate that digital literacy and ownership of ICT tools do not significantly predict the use of e-government services. However, gender (OR = 1.596, p < 0.000), education level (OR = 1.129, p < 0.013), socio-economic status of the district (OR = 1.124, p < 0.003), and the perception of internet necessity (OR = 1.832, p < 0.000) all show a statistically significant positive association with engagement. Notably, internet access at home is negatively associated with e-government use (OR = 0.167, p < 0.000). Additionally, older individuals are more likely to use e-government platforms (OR = 1.015, p < 0.01), and men engage more frequently than women.

Regarding awareness of IMM mobile applications, several variables were found to be significant predictors. These include male gender (OR = 1.196, p < 0.005), higher educational attainment (OR = 1.255, p < 0.000), higher digital literacy (OR = 1.823, p < 0.000), internet usage at home (OR = 1.555, p < 0.000), and the perception of the internet as a necessity (OR = 1.285, p < 0.000). In contrast, neither age nor the socio-economic status of the respondent’s district had a statistically significant effect in this model.

In the third model, which assesses the use of IMM mobile applications, all independent variables were statistically significant predictors except for the socio-economic status of the district and the perceived necessity of the internet. Notably, the likelihood of application use decreases with age (OR = 0.989, p < 0.000). In contrast, educational attainment, digital literacy, and access to ICT tools emerged as strong predictors, underscoring the enduring importance of digital capital in facilitating meaningful engagement with municipal platforms.

The final model, which examined the following of IMM’s social media activities, showed that all independent variables significantly contributed to predicting this behavior. Contrary to common assumptions, older respondents were more likely to follow municipal updates via social media, echoing the findings from the e-government usage model. This trend may reflect an increased reliance on social media as a source of civic information among older individuals. Overall, the findings highlight the continued importance of education, gender, digital literacy, and access to digital tools in shaping engagement with digital public services.

4.2. Patterns of Engagement in Local Digital Public Services

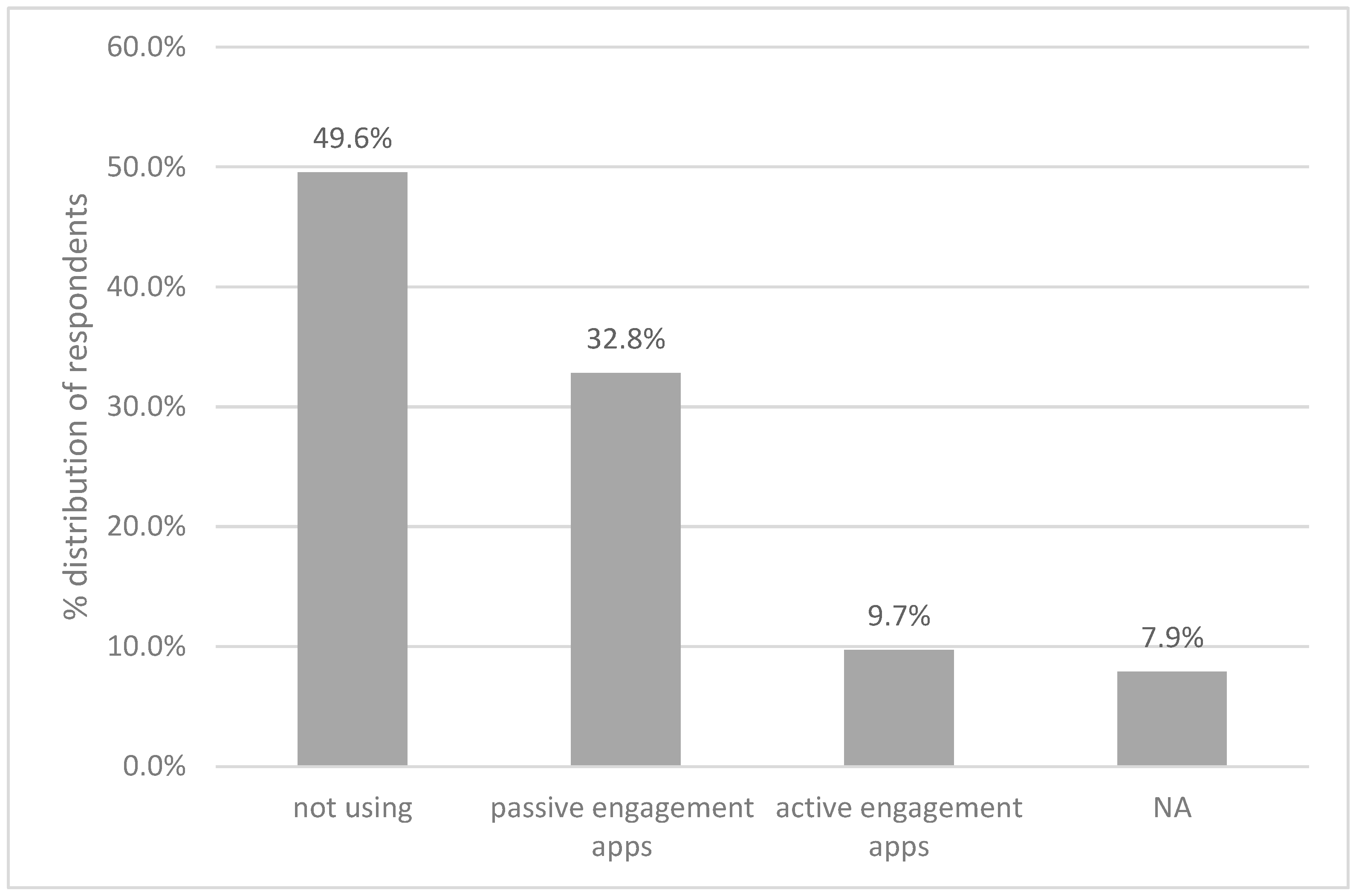

In addition to the logistic regression results, further insights were derived from an open-ended survey question in the IMM Digital Divide Mapping dataset, which asked respondents to identify which IMM applications they use. Responses were thematically coded into two engagement categories: passive and active. Passive engagement refers to the use of applications designed primarily for accessing information—such as those offering public transportation updates, cultural event listings, and other service-related content. These applications, which emphasize information-seeking over interaction, had a usage rate of 32.8% (

Figure 2).

In contrast, active engagement involves the use of applications that support two-way communication and participatory practices, such as submitting complaints, evaluating municipal services, or contributing to spatial planning. These apps facilitate more direct civic interaction but were used by only 9.7% of respondents. Meanwhile, 49.6% of participants reported not using any IMM applications, and 7.9% did not respond to the question. These figures suggest that, while digital tools for service access are widely adopted, platforms that enable active citizen participation remain underutilized.

To better understand these usage patterns, a comparative analysis was conducted based on users’ socio-demographic characteristics. Among those who used any IMM application, 83% had completed high school or higher education. This figure was slightly lower—79.8%—among active engagement app users. In contrast, only 51% of non-users had similar levels of educational attainment. These findings suggest a strong association between higher education and the use of municipal digital platforms.

Gender differences were less pronounced. Males accounted for 56% of those using any IMM application and 54% of non-users. Interestingly, users of active engagement applications were nearly gender-balanced, with women comprising 51%. This suggests that, while overall application usage is slightly higher among men, women are equally likely to engage in participatory digital tools.

Age also played a notable role. The average age of non-users was 49, compared with 38 for users of any IMM application. Among passive engagement app users, the mean age was 37, while for active engagement users, it was slightly higher, at 39. These results indicate that younger individuals are generally more inclined to engage with municipal digital platforms, whereas older adults are significantly underrepresented in both forms of digital engagement.

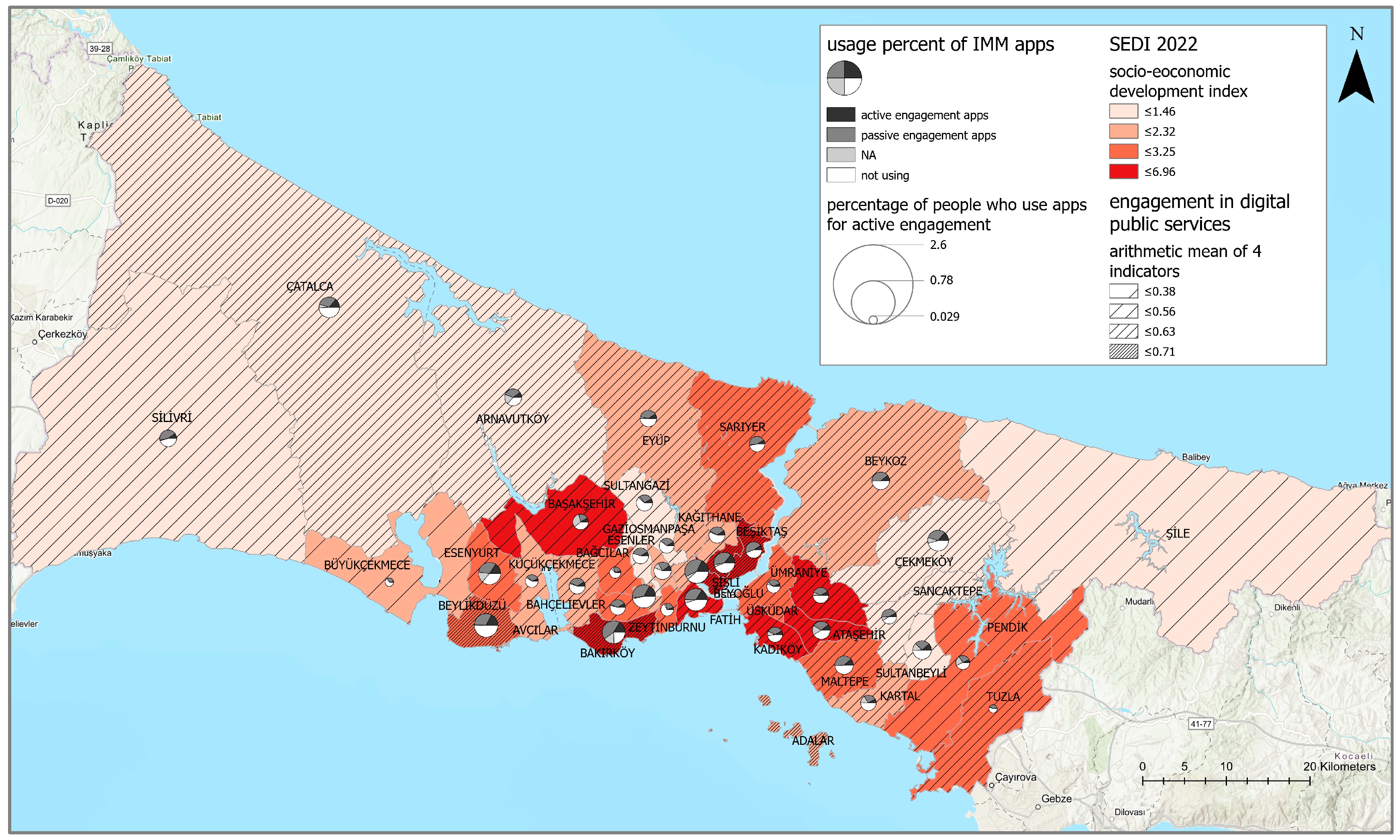

To evaluate spatial patterns of digital engagement, three geographically referenced datasets were overlaid (

Figure 3). The first dataset includes district-level usage rates of IMM applications, classified as enabling either active or passive engagement. The second presents the socio-economic development levels of each district, and the third contains the district-level arithmetic means of four core indicators of digital public service engagement previously analyzed through regression.

The findings reveal significant spatial disparities. The districts with the highest overall usage rates of IMM applications are Bakırköy, Beyoğlu, Beşiktaş, Silivri, and Şişli. In contrast, Zeytinburnu, Büyükçekmece, Bağcılar, Sultangazi, and Gaziosmanpaşa exhibit the highest non-usage rates. Across all districts, passive engagement applications—particularly those focused on information about city services—were more commonly used than those designed for active participation.

For active engagement, the highest usage rates were observed in Beyoğlu, Beylikdüzü, Güngören, Bakırköy, and Fatih. Regarding passive engagement, Beşiktaş, Silivri, Bakırköy, and Sarıyer emerged as leading districts. Active participation is generally higher in socio-economically developed areas, particularly those in central Istanbul. However, exceptions exist—despite their high socio-economic development, districts like Kadıköy, Ümraniye, and Ataşehir exhibit comparatively lower levels of active app usage (

Figure 3).

5. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate how various dimensions of the digital divide—socio-demographic characteristics, digital literacy, physical access to digital tools, and the perceived necessity of the internet—influence citizen engagement with digital public services in Istanbul. Drawing from established frameworks in the digital divide literature [

13,

29,

30], the research hypothesized that disparities in digital access and competencies would shape participation in both e-government platforms and local digital governance tools.

The study is structured around testing these hypotheses in the case of Istanbul—a city that exemplifies the coexistence of advanced digital infrastructure and stark intra-urban socio-economic inequalities. This dual condition makes Istanbul a particularly relevant urban context for investigating how digital inequality manifests within a single metropolitan setting and how it impacts efforts toward democratic and sustainable governance.

The findings corroborate with existing research highlighting the significance of education, digital literacy, and the perceived necessity of the internet in shaping engagement with digital public services. As observed in prior studies [

12,

30], individuals with higher levels of education and stronger digital literacy skills were more likely to be aware of and use IMM mobile applications and to follow municipal activities on social media. In this study, digital literacy—comprising operational, informational, and strategic competencies—proved especially relevant in enabling engagement with local digital governance tools. These results reinforce the idea that access alone is insufficient; individuals must also possess the necessary digital capabilities to fully participate in civic processes and to contribute to more equitable and sustainable urban futures.

One unexpected finding of the study was that digital literacy was not a statistically significant predictor of e-government service use. This outcome challenges earlier assumptions—often found in the digital divide literature—that digital proficiency is a prerequisite for engaging with online public platforms [

7,

19,

30]. A plausible explanation is that e-government services in Turkey have become default access points for essential public services. In such cases, citizens may be compelled to use these platforms regardless of their digital skill level, especially when no alternative service channels are available. This result supports the argument that some types of digital participation—particularly those related to accessing basic services—are driven less by voluntary engagement or digital competence, and more by institutional necessity. It also raises questions about the inclusivity of mandatory digital service models and their implications for equitable and sustainable public service delivery.

Age was shown to be negatively correlated with both digital literacy and the perceived necessity of the internet, confirming findings from previous research [

10,

35]. However, in contrast to prevailing assumptions that younger individuals are more digitally engaged [

7,

19,

30], the analysis revealed that older adults were more likely to use e-government services and follow municipal activities on social media. This finding highlights the need to distinguish between general digital competence and context-specific motivations to engage with public platforms. It also challenges age-based assumptions commonly embedded in digital inclusion policies and emphasizes the importance of designing targeted support mechanisms that consider both age-related needs and service-specific usage patterns.

With respect to gender, the results confirm earlier findings that women face higher barriers in accessing digital public services [

19], despite more recent claims that gender effects are diminishing [

30]. This continuing gender gap underscores the persistence of structural inequalities in digital inclusion, likely compounded by intersecting factors, such as educational attainment, income level, and care responsibilities.

Interestingly, physical access to digital devices—while long assumed to be a foundational factor in digital engagement [

29]—did not consistently predict the use of e-government services in this study. This finding challenges much of the early digital divide literature but may reflect the increasing normalization of online service channels. In contexts where certain essential public services are accessible only through digital means, access becomes a necessity rather than a choice. As a result, individuals may rely on alternative means of access—such as public Wi-Fi, shared devices, mobile data, or assistance from others—thus decoupling device ownership from actual usage. Furthermore, in the Turkish context, mobile service providers such as Turkcell and Vodafone frequently offer unlimited or high-volume mobile data plans, making it common for individuals to forgo fixed-line broadband connections at home. This suggests that, even without household internet access, many residents still maintain consistent digital connectivity through mobile devices. However, the finding that household internet access is negatively associated with e-government service usage further complicates this relationship. These counterintuitive results warrant further investigation, particularly in relation to the shifting meanings of “access” in digital governance contexts where online platforms are increasingly indispensable.

In the spatial analysis, digital participation was more prevalent in districts with higher socio-economic development, supporting prior literature on intra-urban inequalities [

44,

45]. However, some affluent districts still demonstrated low levels of active engagement, suggesting that infrastructure alone does not guarantee participation. As noted before, perceived necessity and digital attitudes may play a mediating role. These findings emphasize the need to go beyond technical solutions by fostering citizen-centered strategies that promote participatory habits and a local digital culture.

Thematic analysis revealed that while, many citizens use IMM apps for information (passive engagement), only a small proportion engage in participatory functions—such as submitting feedback or contributing to planning decisions (active engagement). This gap underscores the need to not only improve access, but also to foster meaningful digital citizenship through civic education and participatory design.

In the broader context of smart governance, these findings highlight the risks of assuming that digital platforms are inherently inclusive. Without targeted efforts to address inequalities in digital skills, perceptions, and socio-economic conditions, smart city initiatives risk reinforcing existing exclusions. Future policy should focus on developing localized digital literacy programs, increasing awareness of participatory tools, and ensuring that platforms are designed with accessibility and inclusion at their core.

E-participation and e-governance offer significant advantages, including accountability, transparency, effective citizen engagement in decision-making processes, and enhanced accessibility to public services [

46]. However, due to digital inequalities, the inclusiveness of these internet-based tools—which also play a central role in smart governance policies—remains an issue that requires further discussion. Indeed, in many urban contexts, significant challenges persist around equitable access to digital services and the skills needed to use them effectively.

Despite claims in some studies that the impact of gender—when assessed in the context of socio-economic factors—has diminished or even disappeared regarding the use of digital technologies [

12,

30], this study reveals that a clear gender gap persists in the use of digital public services, with females showing a greater tendency to engage with these services to a lesser extent. As previously noted in the literature, the relationship between educational attainment, digital literacy, and their influence on the use of digital public services was found to be significant. The correlation analysis of age indicates a strong negative association between age and both digital literacy and the perceived necessity of the internet. Conversely, a positive and statistically significant relationship was observed between age and both the use of e-government services and the following of municipal activities on social media. This trend may be attributed to an increased necessity to access government services and stay informed with age. However, the effect of age on the use of IMM mobile applications is negative, indicating a decline in usage among older individuals. This divergence suggests that age influences different forms of digital engagement in distinct ways—while older adults may engage out of necessity, younger individuals are more inclined toward participatory, non-compulsory digital tools.

The predominant use of municipalities’ mobile applications is for digital access to information regarding a range of municipal services, including complaints about public services, traffic conditions, public transportation, parking spaces, and occupancy rates. Studies examining the digital divide and digital governance with regional conditions have reported findings based on urban–rural disparities [

47,

48,

49]. Additionally, evaluations based on intra-urban and inter-regional socio-economic differences have been conducted [

5,

44,

50]. The findings of this study indicate a strong positive correlation between the socio-economic development of districts and both digital literacy and the perceived necessity of internet access. Even within the same country and city, there are notable differences in access to and effective use of digital technologies. The usage of e-government services and one’s following of the municipality’s activities on social media are still influenced by geographical factors. These spatial patterns of digital engagement reaffirm the role of place-based socio-economic inequalities in shaping not only access but also the depth and quality of participation. This highlights the importance of targeted, district-level strategies in advancing inclusive digital governance and addressing uneven patterns of civic engagement.

In addition, the findings indicate that digital literacy has an insignificant effect on the utilization of e-government services, similar to the variable of age. It is plausible that the impact of this relationship is neutralized because these services have become default and non-optional channels for accessing essential public services, with no viable offline alternatives. Nevertheless, digital literacy emerges as a significant factor in following local services on social media and in increasing awareness and use of municipal mobile applications. Ownership of ICT devices also does not significantly affect e-government usage, suggesting that citizens may find alternative access routes—such as public Wi-Fi or assistance from others—when device ownership is lacking. Conversely, local digital governance tools play a stronger role in enhancing citizen awareness, promoting the use of participatory platforms, and enabling the monitoring of municipal activities via social media.

Another finding that deviates from prior literature is the unexpected negative association between household internet access and the use of e-government services. A likely explanation is that, even in the absence of home internet access, citizens are compelled to engage with e-government platforms due to the essential nature of the services offered. This necessity may lead users to rely on mobile data or shared devices, creating a paradox where lower connectivity does not reduce—and may even correlate with higher—usage of certain platforms.

Perceiving the internet as a necessity remains a key variable that positively influences both awareness and use of digital public services and municipal social media. Together, these results challenge traditional assumptions in digital divide literature, highlighting how access, motivation, and structural necessity interact in complex ways in digitally mandated service environments. They also suggest a shift in the nature of digital inequality—where the issue is no longer only about owning technology, but also about navigating compulsory digital systems under unequal conditions.

6. Conclusions

In the context of smart governance, bridging the digital divide is essential to achieving more efficient, transparent, and participatory public administration, where services and civic participation processes are increasingly mediated through digital platforms. Unaddressed inequalities in access, skills, and attitudes toward digital technologies risk reinforcing existing socio-economic disparities, thereby excluding significant portions of the population from the benefits of digital governance.

This study contributes to the ongoing discourse on sustainable urban governance by offering a localized analysis of digital inequality and citizen engagement in Istanbul. The findings show that multiple dimensions of the digital divide—including socio-demographic factors, digital literacy, and perceptions of necessity—shape patterns of digital public service use. Importantly, the results highlight that access alone does not guarantee meaningful participation; rather, digital inclusion requires targeted interventions that address skills, motivation, and structural accessibility.

Future research and policy should prioritize context-specific and inclusive digital strategies that align with broader sustainability goals, particularly in rapidly urbanizing cities facing high levels of intra-urban inequality. As demonstrated by the Istanbul case, cities that pair technological innovation with equity-oriented digital inclusion efforts are better positioned to foster resilient and sustainable urban futures.