Deconstructing Sustainability Challenges in the Transition to a Four-Day Workweek: The Case of Private Companies in Eastern Europe

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Background on the 4DWW Model

2.2. The Three-Level Analytical Framework for Assessing Organizational Outcomes

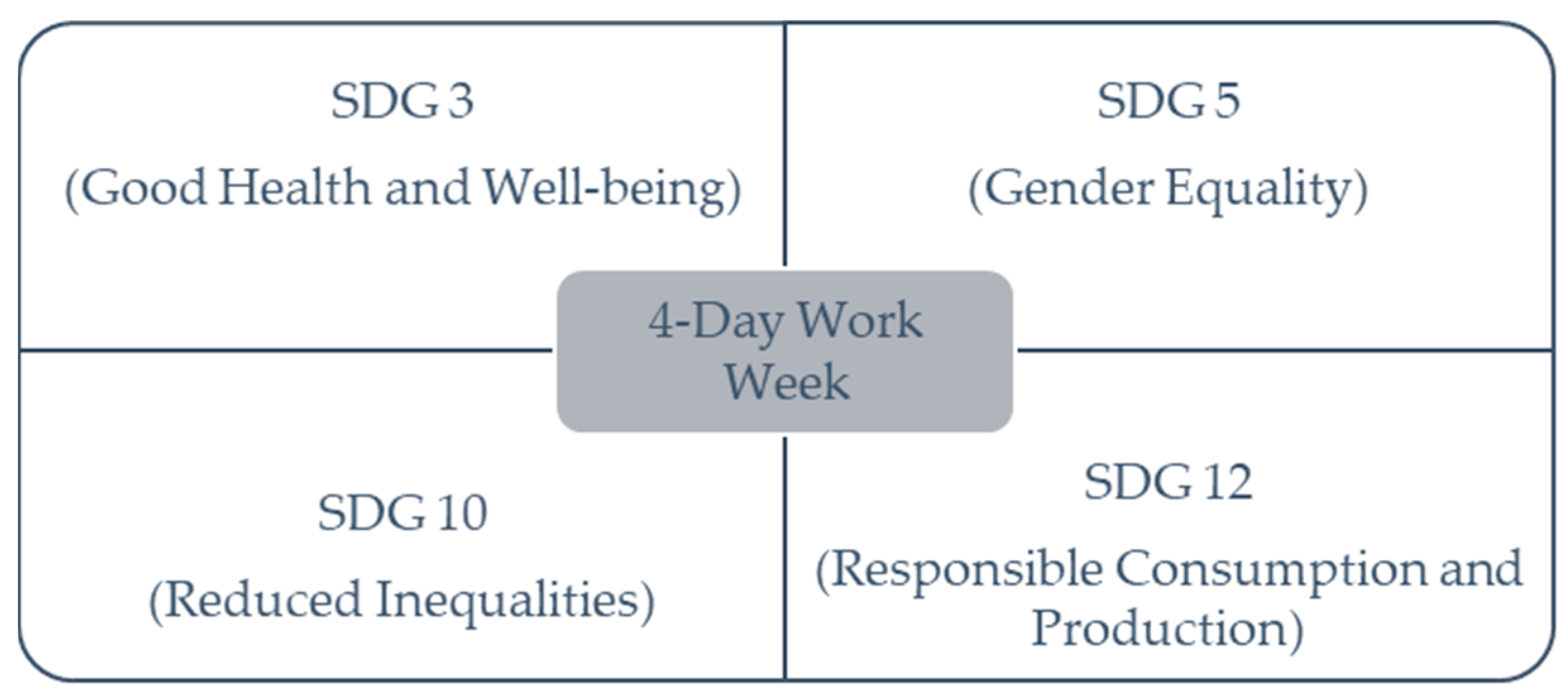

2.3. The 4DWW and SDGs: Opportunities for Sustainability

3. Research Methodology: Empirical Context, Data Collection and Analysis Methods

4. Results

4.1. Main Advantages of Transition to 4DWW Model

4.2. Main Challenges of Transition to 4DWW Model

4.3. Impact of Transition to 4DWW Model

- Sales Volume and Revenue. These indicators are one of the most fundamental KPIs in any business. Sales volume reflects the number of goods sold, while revenue represents the total monetary value generated by these sales over a specific period. In traditional workweek models, these metrics are often maximized by ensuring efficient, continuous operations. Bockerman & Ilmakunnas, argue that increased employee satisfaction leads to higher productivity [42], so in case employees’ satisfaction increases with a transition to a 4DWW it is possible not only to maintain but also to improve these KPIs. Furthermore, reduced workdays may lead to more focused and effective work, as employees concentrate on critical tasks, avoiding procrastination and unnecessary breaks. However, it is possible that businesses adopting a 4DWW may face challenges in maintaining or increasing sales compared to traditional 5-day work schedules. For example, one of the companies that took part in a 4-Day Work Week Pilot Project in the UK quit the project earlier, facing problems maintaining workload, increased fatigue levels among employees as well as scheduling difficulties [43]. A systemic review of 4DWW-related articles demonstrated that while there is a clear positive impact on job satisfaction, cost reductions, and reduced turnover, the impact on productivity was inconclusive [44]. Hence, there are concerns that the reduced work hours could limit the overall productive capacity of the workforce, potentially leading to lower sales volumes despite optimization efforts.

- Order Fulfillment Rate. It measures a company’s ability to deliver products to customers on the first attempt. This KPI is essential in wholesale because it directly impacts customer satisfaction, loyalty, and future sales [45] A high fulfillment rate indicates that the company can efficiently manage inventory, logistics, and communication, ensuring timely delivery. A smooth supply chain allows businesses to meet customer expectations consistently, and interruptions or delays can lead to decreased customer trust [46]. In the context of a 4DWW, the challenge lies in maintaining fulfillment rates with fewer working hours, as the compressed schedule could make it more challenging for employees to complete all necessary tasks, potentially resulting in delays or inefficiencies that could impact customer service. Reduced work time may also limit the ability to handle unexpected events or fluctuations in demand, which could negatively affect order fulfillment.

- Employee productivity (Sales per Employee). This KPI measures the average revenue generated by each employee over a given period. For a wholesale company, maintaining or improving sales per employee is critical for demonstrating that the reduced workweek does not negatively impact overall output. The “Law of Diminishing Returns” indicates that beyond a certain point, additional working hours can reduce efficiency [47], so reducing the number of working days may mitigate this by allowing employees to rest and recharge, leading to higher productivity levels within the remaining work hours. The concept of “work intensification” posits that employees tend to focus more when working hours are compressed, driving higher per-hour productivity [48].

- Employee Turnover Rate. It measures the rate at which employees leave the company relative to the average number of employees. High turnover rates can indicate dissatisfaction, burnout, or better opportunities elsewhere, while low turnover often suggests a stable and satisfied workforce [49]. Employee retention is closely tied to job satisfaction, work-life balance, and organizational commitment [50,51]. The Job-Demands Resources Model emphasizes that reducing excessive job demands (like long workweeks) while providing adequate resources (e.g., flexibility, and support) can lead to higher employee engagement and retention [52]. A 4DWW may provide a better work-life balance, which could reduce burnout and enhance loyalty, thereby lowering turnover rates.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Empirical Data: Companies and Interviewees

| Code | Organization | Activity | Size by Employees | Company’s Age | Interviewer Position | Source |

| C1 (LT) | Lithuanian Employers’ Confederation | Association | Not relevant | 25 | Director-General | URL (accessed on 2 February 2025). https://www.delfi.lt/verslas/verslas/4-darbo-dienu-savaite-isbande-lietuviai-minusu-nemato-taciau-darbdaviai-sako-zmones-nori-dirbti-120036828 |

| C2 (LT) | OBDeleven | Service (Computer software development) | 84 | 11 | Chief Marketing Officer | URL (accessed on 2 February 2025). https://www.vz.lt/verslo-valdymas/2024/04/13/trumpesne-darbo-savaite-tenkina-ne-visus-bet-isbandyti-verta |

| C3 (LT) | Oxylabs | Computers and software | 233 | 16 | Executive Director | URL (accessed on 2 February 2025). https://www.vz.lt/verslo-valdymas/2024/05/14/vos-valanda-trumpesne-darbo-diena-ir-darbuotojai-kur-kas-laimingesni |

| C4 (LT) | Leinonen | Service (accounting, consulting) | 95 | 28 | Specialist | |

| C5 (LT) | Manpower Lit | Service (innovative HR and workforce solutions) | 254 | 19 | Business Operations Manager | |

| C6 (LT) | Vilniaus šilumos tinklai | Energy | 593 | 27 | Director | URL (accessed on 2 February 2025). https://www.vz.lt/verslo-valdymas/2023/08/13/mokslininkai-rekomenduoja-penktadieniais-nedirbti |

| C7 (LV) | Latvian Employers’ Confederation | Association | Not relevant | 25 | Director-General | URL (accessed on 5 February 2025). https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=918287397060527 https://nra.lv/ekonomika/latvija/476952-lddk-prezidents-sobrid-vajadzetu-stradat-pat-sesas-dienas-nedela.htm |

| C8 (LV) | SmartHR | Service (HR consulting) | 5 | 13 | Director | URL (accessed on 5 February 2025). https://smarthr.lv/4-darba-dienu-nedela-smarthr-pieredze |

| C9 (LV) | DeskTime | Service (programming) | 29 | 7 | Director | URL (accessed on 5 February 2025). https://labsoflatvia.com/en/news/does-latvia-need-a-four-day-workweek |

| C10 (LV) | Scoro Software | Service (programming) | 11 | Talent acquisition specialist | URL (accessed on 5 February 2025). https://www.lsm.lv/raksts/zinas/ekonomika/vai-cetru-dienu-darba-nedela-latvija-ir-iespejama-un-nepieciesama.a494413/ | |

| C11 (EE) | Scoro Software OÜ (Scoro) | Business Management Software for Service Firms | 90 | 2 | Human resources manager | URL (accessed on 10 February 2025). https://talenthub.ee/kaks-aastat-hiljem-scoro-ja-talenthub-toestavad-et-neljapaevane-toonadal-suurendab-tootajate-produktiivsust-ja-rahulolu/ |

| C12 (EE) | TalentHub | Recruitment Agency | 8 | 6 | Co-founder | URL (accessed on 3 February 2025). https://talenthub.ee/kaks-aastat-hiljem-scoro-ja-talenthub-toestavad-et-neljapaevane-toonadal-suurendab-tootajate-produktiivsust-ja-rahulolu/ |

| C13 (EE) | Elisa Eesti AS | Telecommunication | 894 | 30 | Technology unit manager | URL (accessed on 7 February 2025). https://www.aripaev.ee/saated/2024/05/16/elisa-neljapaevane-toonadal-on-firmakultuuri-kusimus |

| C14 (EE) | SMARTFUL Growth OÜ | Recruitment agency | 6 | 5 | Founder, CEO | URL (accessed on 2 February 2025). https://dspace.ut.ee/server/api/core/bitstreams/d29b33ea-e728-4372-92ac-a01c3322c9e3/content |

| C15 (EE) | Solutional OÜ | Software development | 12 | 5 | Assistant | |

| C16 (EE) | Postimees Grupp AS | Publishing of newspapers | 487 | 28 | Human resources manager | URL (accessed on 3 February 2025). https://dspace.ut.ee/server/api/core/bitstreams/d29b33ea-e728-4372-92ac-a01c3322c9e3/content |

| C17 (EE) | Tele2 Eesti AS | IT and mobile provider | 378 | 26 | Human resources manager | URL (accessed on 5 February 2025). https://digi.geenius.ee/blogi/tehnikast-ja-trendidest-blogi/eestis-on-ettevote-kus-saab-piiramatult-puhata-aga-kes-siis-tood-teeb/ |

Appendix B. List of Questions Used in the Structured Interviews for the Case Company

- What is your name; surname, position in the company and working experience

- 2.

- What challenges did the company face during the transition to a 4DWW?

- 3.

- How has the 4DWW affected your productivity?

- 4.

- Do you feel that your workload is manageable within the 4DWW structure?

- 5.

- Have you observed any changes in health and well-being?

- 6.

- How has your overall work experience changed since the implementation of the 4DWW?

- 7.

- What are the biggest advantages and disadvantages of the 4DWW for you personally?

- 8.

- How has the reduction in workdays affected your commuting patterns and transportation costs?

- 9.

- Are there any environmental benefits the company has experienced due to the 4DWW? (This question is for managers only)

References

- Jahal, T.; Bardoel, A.; Hopkins, J.L. Could the 4-day Week work? A Scoping Review. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2023, 62, e12395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamermesh, D.; Biddle, J.E. Days of Work over a Half Century: The Rise of the Four-Day Week. SSRN Electron. J. 2022, 15325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komlosy, A.; Watson, J.K.; Balhorn, L. Work: The Last 1000 Years; Verso: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pullinger, M. Working time reduction policy in a sustainable economy: Criteria and options for its design. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 103, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Q.; Rodríguez-Labajos, B. Does decreasing working time reduce environmental pressures? New evidence based on dynamic panel approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 125, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, A.S.-K. Creating more sustainable careers and businesses through shorter work weeks. Lead. Lead. 2020, 2020, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppanner, L.; Maume, D.J. Shorter Work Hours and Work-to-Family Interference: Surprising Findings from 32 Countries. Soc. Forces 2016, 95, 693–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Q.; Shen, S. When reduced working time harms the environment: A panel threshold analysis for EU-15, 1970–2010. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, R.L.; Weaver, K.M. Four factors influencing conversion to a four-day work week. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1977, 16, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Josh Bersin Company. The Four-Day Work Week: Learnings from Companies at the Forefront of Work-Time Reduction (p. 2). 2023. Available online: https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/cmte_testimony/2024/fin/1Z7cJqwZB-VALczY9QJ8VbrhD_VYDlf_z.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Abrams, Z. Rise of the 4-Day Workweek. 2025. Available online: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2025/01/rise-of-4-day-workweek (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- 4 Day Work Week Global. 2023 Long Term Pilot Report (p. 4). Autonomy Research. 2024. Available online: https://www.4dayweek.com/long-term-2023-pilot-results (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Sng, M.; Khor, W.; Oide, T.; Suchar, S.C.; Tan, B.C. Effectiveness of a Four-days/Eight Hour Work a Week. 2021. Available online: https://commons.erau.edu/ww-research-methods-rsch202/21 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Laker, B. How Far-Reaching Could the Four-Day Workweek Become? MIT Sloan Management Review. 2023. Available online: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/how-far-reaching-could-the-four-day-workweek-become/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Li, X.; Guan, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wu, M. Future work self and employee workplace well-being: A self-determination perspective. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 124, 103522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. Employee well-being and organizational performance: A strategic HR perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 2024, 109, 412–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Ros, L.; Pennucci, F.; De Rosis, S. Unlocking organizational change: A deep dive through a data triangulation in healthcare. Manag. Decis. 2023, 61, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundari, S.; Kusmiati, M. Training needs analysis of operational. Perwira Int. J. Econ. Bus. 2022, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanger, F.; Watson-Manheim, M.B.; Swan, B.R. A multi-level socio-technical systems telecommuting framework. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2013, 32, 1257–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gren, L. Agile practices and team performance: The role of interpersonal conflict. J. Syst. Softw. 2019, 147, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanova, V.; Stoyanov, S. From operational capability to dynamic sustainability: A three-level process model in banking. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 1892–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Sustainable Competitiveness: Policies for Long-Term Growth. Publications Office of the European Union. 2016. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52016DC0739 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Moallemi, E.A.; Malekpour, S.; Hadjikakou, M.; Raven, R.; Szetey, K.; Bryan, B.A. Early systems change necessary for catalyzing long-term sustainability in a post-2030 agenda. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Torres, M.J.; Fernández-Izquierdo, M.Á.; Rivera-Lirio, J.M. Green supply chain management and corporate sustainability: Strategic alignment and long-term competitiveness. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 384, 135618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbya, H.; McKelvey, B. Toward a complexity theory of information systems development. Inf. Technol. People 2006, 19, 12–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czernek-Marszałek, K.; Klimas, P. Levels of cooperation strategy: Individual, operational, and strategic dynamics. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2024, 20, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Mazzucato, M.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockström, J. Six Transformations to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda-Parr, S. From the Millennium Development Goals to the Sustainable Development Goals: Shifts in purpose, concept, and politics of global goal setting for development. Gend. Dev. 2016, 24, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, P.; Costa, L.; Rybski, D.; Lucht, W.; Kropp, J.P. A Systematic Study of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Interactions. Earth’s Future 2017, 5, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekins, P.; Zenghelis, D. The costs and benefits of environmental sustainability. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 949–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariappanadar, S. Improving Quality of Work for Positive Health: Interaction of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8 and SDG 3 from the Sustainable HRM Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 4 Day Work Week Global. The Results Are in: The UK’s Four-Day Week Pilot; Autonomy Research: Hampshire, UK, 2023; p. 6. Available online: https://autonomy.work/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/The-results-are-in-The-UKs-four-day-week-pilot.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Eicker, J.; Keil, K. Who cares? Towards a convergence of feminist economics and degrowth in the (re)valuation of unpaid care work. In Exploring Economics; 2018. Available online: https://www.exploring-economics.org/en/discover/who-cares/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Henley Business School. Four Better or Four Worse? A White Paper on the 4-day Work Week; Henley Business School: Henley-on-Thames, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Malone, D.; EY Ireland. What Impact Would a Reduced Working Week Have on Sustainability. 2023. Available online: https://www.ey.com/en_ie/sustainability/what-impact-would-a-reduced-working-week-have-on-sustainability (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Rosnick, D.; Weisbrot, M. Are Shorter Work Hours Good for the Environment? A Comparison of U.S. and European Energy Consumption. Int. J. Health Serv. 2007, 37, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildizhan, H.; Hosouli, S.; Yılmaz, S.E.; Gomes, J.; Pandey, C.; Alkharusi, T. Alternative work arrangements: Individual, organizational and environmental outcomes. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallis, G.; Kalush, M.; O’Flynn, H.; Rossiter, J.; Ashford, N. “Friday off”: Reducing Working Hours in Europe. Sustainability 2013, 5, 1545–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, A.; Court, V.; Sovacool, B.; Sorrell, S. A systematic review of the energy and climate impacts of teleworking. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 093003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubert, S.; Bader, C.; Hanbury, H.; Moser, S. Free days for future? Longitudinal effects of working time reductions on individual well-being and environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 82, 101849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, I.; Purba, H.H. A systematic literature review of key performance indicators (KPIs) implementation. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. Res. 2020, 1, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockerman, P.; Ilmakunnas, P. The Job Satisfaction-Productivity Nexus: A Study Using Matched Survey and Register Data. SSRN Electron. J. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 4 Day Work Week Global. The 4 Day Week UK Results. 2023. Available online: https://www.4dayweek.com/uk-pilot-results (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Campbell, T.T. The four-day work week: A chronological, systematic review of the academic literature. Manag. Rev. Q. 2023, 74, 1791–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumalai, S.; Sinha, K.K. Customer satisfaction with order fulfillment in retail supply chains: Implications of product type in electronic B2C transactions. J. Oper. Manag. 2004, 23, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, E.; Karikari, D.; Agbanu, C.; Martey, M.; Poku, M. Impact of supply chain management practices on customer satisfaction: An exploratory study of medium to large enterprises in Ghana. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2022, 1, 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Milgram, L. Law of Diminishing Returns. In Managing Smart; Elsevier EBooks: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; p. 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelliher, C.; Anderson, D. Doing more with less? Flexible working practices and the intensification of work. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suraihi, W.A.A.; Samikon, S.A.; Suraihi, A.-H.A.A.; Ibrahim, I. Employee turnover: Causes, importance and retention strategies. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2021, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdirahman, H.I.H.; Najeemdeen, I.S.; Abidemi, B.T.; Ahmad, R. The Relationship between Job Satisfaction, Work-Life Balance and Organizational Commitment on Employee Performance. Adv. Bus. Res. Int. J. 2020, 4, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irabor, I.E.; Okolie, U.C. A Review of Employees’ Job Satisfaction and its affect on their Retention. Ann. Spiru Haret Univ. Econ. Ser. 2019, 19, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W. A Critical Review of the Job Demands-Resources Model: Implications for Improving Work and Health. Bridg. Occup. Organ. Public Health 2014, 1, 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thébaud, S.; Hoppen, C.; David, J.; Boris, E. Understanding Gender Disparities in Caregiving, Stress, and Perceptions of Institutional Support among Faculty during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Chakrabarti, S.; Grover, S. Gender differences in caregiving among family—Caregivers of people with mental illnesses. World J. Psychiatry 2016, 6, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ReferencesBerkery, E.; Peretz, H.; Tiernan, S.; Morley, M.J. The impact of flexi-time uptake on organizational outcomes and the moderating role of formal and informal institutions across 22 countries. Eur. Manag. J. 2024; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.J.; Chouliara, N.; Blake, H. From Five to Four: Examining Employee Perspectives Towards the Four-Day Workweek. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Baggethun, E. Rethinking work for a just and sustainable future. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 200, 107506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Role | Work Experience |

|---|---|

| President of the company (founder) (M1 (LV)) | 31 years in the case company, >50 years overall |

| CEO (M2 (LV)) | 31 years in the case company, >35 years overall |

| Accountant (S1 (LV)) | 6 years in the case company, >25 years overall |

| Sales director (S2 (LV)) | 9 years in the case company, >10 years overall |

| Manager (S3 (LV)) | 29 years in the case company, >40 years overall |

| Warehouse employee (S4 (LV)) | 5 years in the case company, >40 years overall |

| Warehouse employee (S5 (LV)) | 7 years in the case company, >30 years overall |

| Warehouse supervisor (S6 (LV)) | 7 years in the case company, >30 years overall |

| Theme | Example of the Answers |

|---|---|

| Improved work-life balance | I started taking yoga classes and I feel much better mentally and physically now (S1 (LV)) I usually spend my weekends doing house chores, and by Monday I was already tired, now I spend Friday and Saturday to do everything I need, and Sunday is my relaxation day, so on Monday I am fully recharged and ready to work (S3 (LV)) |

| Extra time for personal activities and/or time with family | I finally have time to travel. I often travel somewhere around the country at least once a month now, in addition to an annual vacation (S1 (LV)). I can now spend more time with my daughter and my husband (S5 (LV)). |

| Lowered stress-levels | I feel more rested and did not have a burnout in a while (M1 (LV)). I used to be very stressed about not spending enough time with my daughter, feeling guilty all the time, now this guilt is gone (S6 (LV)). |

| Challenge | Example of the Citations and Answers |

|---|---|

| Individual Level | |

| Stress and burnout caused by changes | This can create significant stress and lead employees to burnout (C3 (LT)) Each of us has been pushed out of our comfort zone (C6 (LT)) For employees who had already optimized their workday prior to the experiment, the need to fit their weekly workload into four days began to create a sense of stress (C8 (LV)) Fewer workdays won’t automatically mean less work (C9 (LV)) |

| Increased work intensity | The workday becomes more intense, and not everyone knows how to work in this way (C6 (LT)) We realized that a four-day workweek would require more staff to manage the workload, as some employees felt excessive pressure trying to complete five days’ worth of work in four days during the trial. However, we haven’t observed this issue with unlimited vacation (C17 (EE)) |

| Extra time to adjust to changes Work-life balance adjustments | After six months, we found that around 60–70% of employees had learned to complete everything within four working days (C6 (LT)) The to-do list still had tasks with deadlines, so there were a few workdays when I had to work outside of standard working hours (C8 (LV)) |

| Anger of loved ones over inequality | Dealing with the anger of loved ones over inequality is time for yourself (C10 (LV)) |

| Employee resistance to change | Persuading all specialists to agree to the new schedule was initially difficult (M2 (LV)) |

| Operational level | |

| The complexity of coordinating meetings within the company and with external partners | Due to shorter working hours or varying start times (employees starting their workday at 8 or 9 AM), it may become more challenging to coordinate meeting times (C4 (LT)) |

| Loss of team synergy and working efficiency | It may become more challenging to coordinate and complete all tasks effectively within a shorter timeframe (C3 (LT)) |

| Workflow restructuring | Not all employees are able to plan their tasks effectively. Not all employees manage to finish their work earlier (C5 (LT)) Such a schedule is possible for a team when the work content allows for planning and does not require an operational response. To compensate for one day off, businesses will be forced to hire additional employees to ensure the production of products and provision of services at the previous level (C8 (LV)) |

| Client and customer expectations | Most customers and partners were still working standard business hours and expected us to be reachable on Friday (C8 (LV)) |

| Reorganization of paperwork | The reorganization of paperwork, particularly the need to amend employee contracts, are the most significant obstacle (M1 (LV)) |

| Challenges in onboarding new employees | New employees accustomed to a five-day workweek require clear onboarding guidelines and training materials. “The onboarding program was one of the key topics we thoroughly discussed during the preparation process. As of today, we have various guidelines and video trainings that explain our work arrangements and emphasize that the four-day workweek is not a given but rather the result of our collective effort and commitment. During onboarding, we primarily focus on introducing the work culture, setting expectations, and developing practical skills (C11 (EE)). Best practices and work techniques, such as smart time management—which is crucial for a four-day workweek—are an integral part of the program. It all starts with being aware of how you spend your time daily. Only then can you make the necessary adjustments to your work arrangements (C12(EE)) |

| The needed extra investment, time and preparational works for transition | We have seen that thorough preparation and the restructuring of work processes are essential cornerstones on which our success has been built so far C11(EE) It’s simply about organizing your work more efficiently. This is a process that takes time—it took us over a year to refine habits and optimize work processes. Now, this year, we have achieved all our goals without reducing them or working overtime C12(EE) |

| Strategic level | |

| Risk of productivity maintain and decrease | Not all teams managed to maintain the required pace, which resulted in an overall decrease in productivity (C3 (LT)) The argument that we need to work less and smarter is hardly correct, because to increase productivity we need to work longer and harder, as the experience of developed countries has shown (C7 (LV)) And even if, at first, we might be able to significantly increase our productivity, then in a long-term we’ll have to find ways to further optimize our workload by automating, delegating, or outsourcing some tasks (C9 (LV)) |

| Risk of quality decrease | For IT teams, software release cycles had to be adjusted—they were shortened by one day, which required changes to expectations about what could be accomplished in a two-week period. Additionally, IT teams released updates or necessary changes less frequently (C2 (LT)). We can try to increase employee productivity and keep production at the same levels, however, in such a scenario, there is a high risk that this would come at the cost of product quality (C9 (LV)) |

| Industry-specific constraints | For many manufacturing companies, a 20% reduction in working hours will directly translate into a 20% reduction in goods produced (C9 (LV)) |

| Risk of competitiveness decrease | In terms of competitiveness, we would definitely be left behind because not all sectors are truly capable, and not everyone actually needs this (C1 (LT)) |

| KPI | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 * | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sales Volume | 20,615 | 25,543 | 20,464 | 19,952 | 27,120 | 34,572 | 37,104 | 43,568 | 44,072 | 56,112 |

| Revenue | 70,137 | 66,965 | 71,674 | 76,208 | 114,154 | 158,238 | 209,347 | 278,769 | 256,992 | 284,826 |

| Order Fulfillment Rate | 94% | 92% | 96% | 96% | 96% | 97% | 98% | 98% | 98% | 98% |

| Employee productivity | 3435.8 | 4257.1 | 2558 | 2494 | 3390 | 4321.5 | 4638 | 5446 | 5509 | 7014 |

| Employee Turnover Rate | 0 | 0 | 0.13 | 0 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SDG | Example of Answers and Contribution of Company Representative |

|---|---|

| SDG3 (Good Health) | I started taking yoga classes and I feel much better mentally and physically now (S1 (LV)) I can now have doctor appointments on Fridays, instead of requesting day-offs during the work week, it makes it much easier to manage my health (S4 (LV)) |

| SDG5 (Gender Equality) | I can now spend more time with my daughter, and I don’t feel like I am a bad mother (S6 (LV)) |

| SDG10 (Reduced Inequalities) | As I was getting older, it was harder to maintain my productivity at work. The 4DWW gives me more time for recovery, so I don’t feel as overwhelmed as before (S2 (LV)) |

| SDG13 (Climate Action) | I’m saving money on gas, and not having to deal with traffic five days a week is a huge relief (M1 (LV)) We are using less water and electricity now, we could’ve used less heating as well, but we have central heating that we cannot control, unfortunately (M1 (LV)) It is not very noticeable, but the amount of waste we are creating during work has decreased, I think if we consider the yearly amount, it would be quite a lot, actually (M2 (LV)). |

| Challenge Level | Possible Solutions |

|---|---|

| Individual | Providing training on time-management to the employees with the 4DWW schedule can help them tackle the problem of feeling overwhelmed with the number of tasks necessary to be performed within a shorter period of time and avoid burnout. A gradual transition period allowing the workers to adjust to a new schedule may be helpful. Raising awareness among the decision-makers in the company, for example, via consultation with “4 Day Week Global” representatives can help clarify the benefits and fight fears regarding the transition. |

| Operational | On-call at home (employees must be reachable by phone or be ready to work in the event of an unforeseen situation or must arrive at the workplace within two hours or promptly log in to their computer if the task can be completed remotely). Implementation of systems and processes that allow tasks to be delegated to other teams or colleagues. Internal meetings are limited to a maximum of 30 min, and participants are expected to come prepared and leave with agreed-upon next steps. Solutions for the digitization and automation of tasks. |

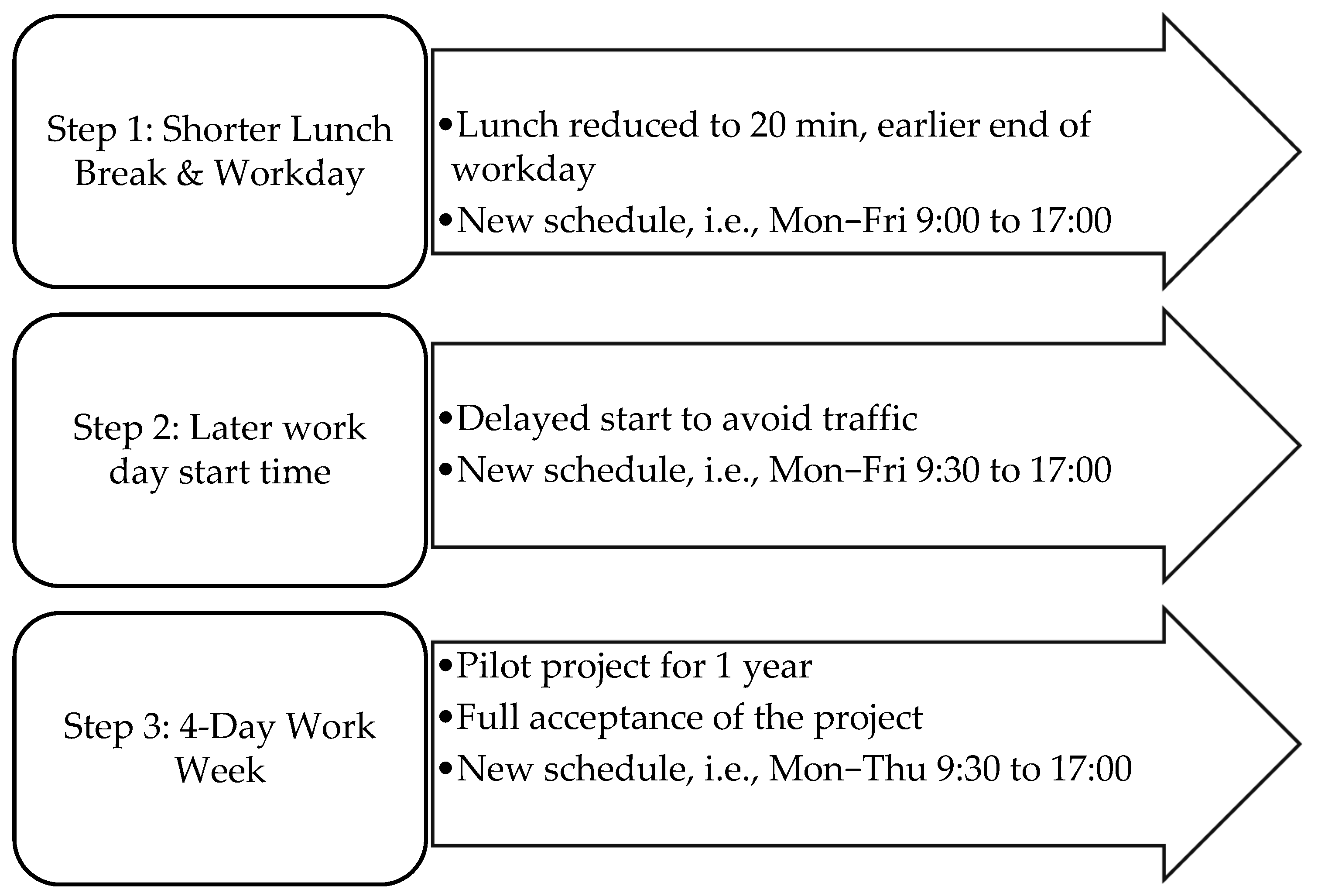

| Strategic | Transition in stages—first, test and adapt the company’s operational processes to the “Shorter Friday” or “Availability Hours” models. Transition in seasons—apply 4DWW model when the season of activities in company is low. Partial transition, where only a part of the company operates under the 4DWW model. Ensuring internal fairness for colleagues who cannot work in the four-day workweek regime. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tambovceva, T.; Veckalne, R.; Järvis, M.; Bruneckienė, J. Deconstructing Sustainability Challenges in the Transition to a Four-Day Workweek: The Case of Private Companies in Eastern Europe. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4904. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114904

Tambovceva T, Veckalne R, Järvis M, Bruneckienė J. Deconstructing Sustainability Challenges in the Transition to a Four-Day Workweek: The Case of Private Companies in Eastern Europe. Sustainability. 2025; 17(11):4904. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114904

Chicago/Turabian StyleTambovceva, Tatjana, Regina Veckalne, Marina Järvis, and Jurgita Bruneckienė. 2025. "Deconstructing Sustainability Challenges in the Transition to a Four-Day Workweek: The Case of Private Companies in Eastern Europe" Sustainability 17, no. 11: 4904. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114904

APA StyleTambovceva, T., Veckalne, R., Järvis, M., & Bruneckienė, J. (2025). Deconstructing Sustainability Challenges in the Transition to a Four-Day Workweek: The Case of Private Companies in Eastern Europe. Sustainability, 17(11), 4904. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114904