Sustainable Human Resource Management and Career Quality in Public Utilities: Evidence from Jordan’s Electricity Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

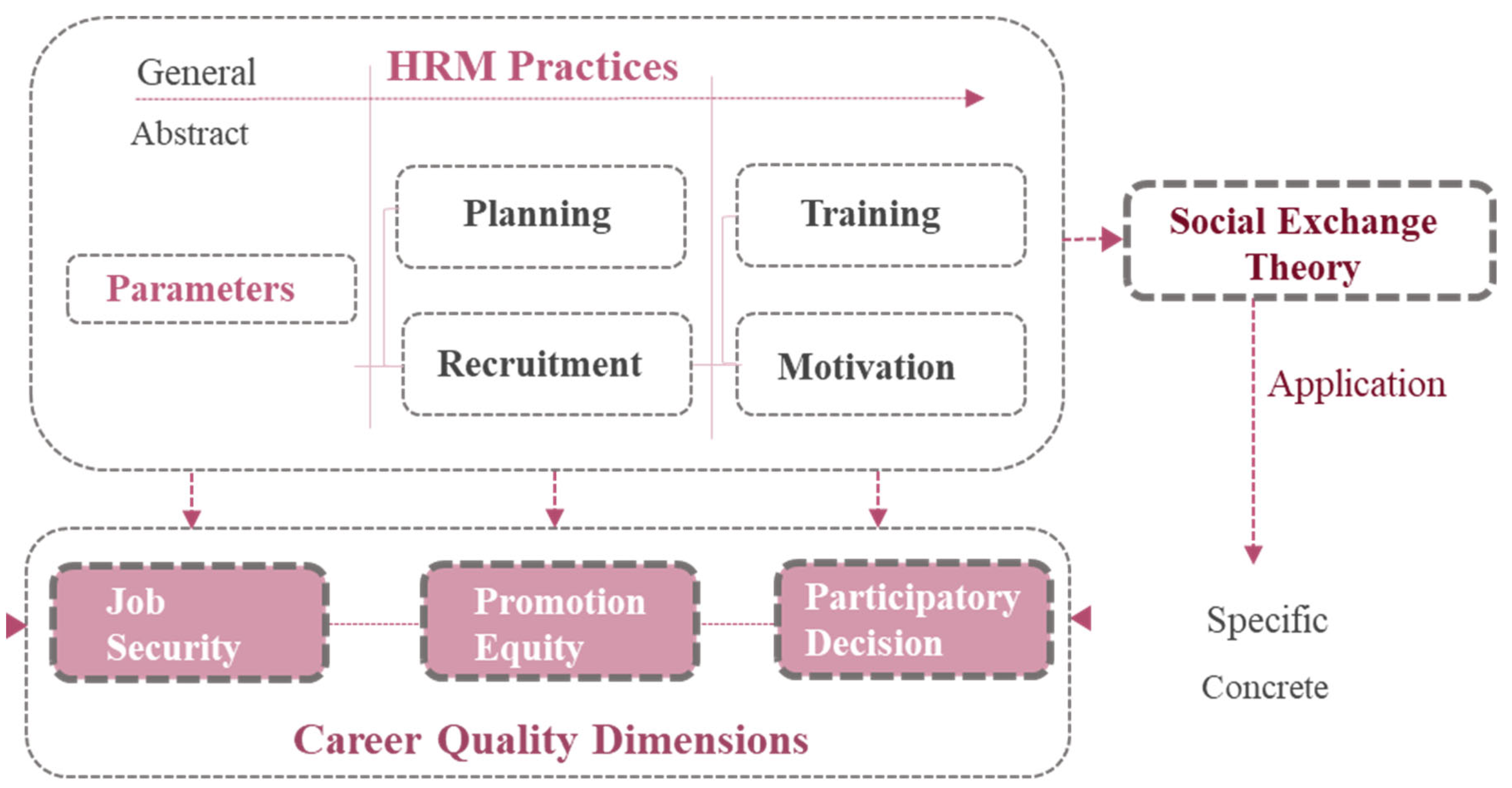

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.1.1. Sustainable Human Resource Management (HRM)

2.1.2. Career Quality

2.1.3. Socio-Cultural Context of HRM in Jordan

2.2. HRM Practices and Career Quality

2.2.1. Strategic Planning

2.2.2. Transparent Recruitment

2.2.3. Targeted Training

2.2.4. Intrinsic Motivation

2.3. Research Gaps and Theoretical Integration

2.4. Conceptual Model

- The general hypothesis of this study asserts a statistically significant effect of HRM practices on career quality at the Jordanian Electricity Distribution Company. This general hypothesis leads to the following sub-hypotheses regarding the specific impacts of HRM practices:

- H1: Strategic workforce planning positively enhances career quality (job security/promotion equity). Justification: SET argues that long-term workforce planning signals organizational commitment, fostering employee trust and reciprocity [18,21]. At JEDCO, proactive planning (e.g., forecasting skill gaps) reduces layoff anxiety, as evidenced by [49] study in Iraqi utilities (18% reduction in layoff fears). However, bureaucratic inertia may weaken this effect compared to Western contexts.

- H2: Transparent recruitment practices positively enhance career quality (promotion equity and participation). Justification: SET emphasizes fairness as a cornerstone of trust [22]. Merit-based hiring counters tribal favoritism [8], but JEDCO’s reliance on informal networks disrupts reciprocity. AI-driven anonymized screening [24] could restore equity, as shown in Egypt’s EEHC [27].

- H3: Targeted training programs positively enhance career quality (job security and skill-based promotions). Justification: Training fulfills SET’s mutual gains principle: organizations invest in skills, employees reciprocate with adaptability [29]. JEDCO’s technicians report 30% higher job security after smart grid training [5] but bureaucratic workflows limit skill application (54% vs. 89% in South Korea).

- H4: Intrinsic motivation mechanisms (e.g., recognition) positively enhance career quality (job security and engagement). Justification: Intrinsic motivators (autonomy, purpose) align with SET’s psychological contract [25]. At JEDCO, recognition programs increased participation by 25% [40], but tribal hierarchies suppress merit-based reciprocity.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Sample and Sampling Strategy

3.2.1. Population and Sampling

3.2.2. Sampling Technique

3.3. Data Collection Procedure

3.4. Variables and Operationalization

3.5. Validity and Reliability

3.6. Data Analysis

- Descriptive Statistics: Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis, were calculated to assess the normality of data distribution. These statistics provide insights into the characteristics of the sample and help in understanding the basic patterns within the dataset.

- Inferential Statistics: To evaluate the impact of HRM practices on career quality, hierarchical regression analyses were employed for hypothesis testing with a significance level that was set at p < 0.05 for interpreting results, ensuring robustness in the determination of significant relationships between the variables of interest. Hierarchical regression was selected over SEM due to sample size constraints (n = 173). Ref. [81] recommend regression for small-to-moderate samples to avoid overfitting. The analysis was conducted utilizing: SPSS v28.

- To mitigate common method bias, we employed procedural remedies: (1) ensuring respondent anonymity to reduce social desirability bias, (2) separating scale items for independent/dependent variables in the questionnaire, and (3) conducting Harman’s single-factor test, which revealed no dominant factor (largest variance explained = 28.7%, below the 50% threshold). While self-report data remains a limitation, these steps reduce bias risks [82]. While procedural remedies (e.g., anonymization) reduced social desirability bias, self-report data remain subjective. Future studies should triangulate supervisor ratings (e.g., performance metrics) to validate employee perceptions. Additionally, JEDCO’s refusal to disclose tribal affiliations limited moderation analysis of bias effects critical extension requiring further access.

3.7. Ethical Considerations

4. Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.1.1. Demographic Profile

4.1.2. Variable Distributions

- Career Quality: The mean score for career quality was moderate (M = 3.36), as seen in Table 4. This indicates that, while certain aspects are fulfilling, there is substantial room for enhancement, particularly in the realm of participatory decision-making, a theme emphasized in the existing literature [20]. Participatory decision-making at JEDCO scored moderately (M = 3.36), with employees citing limited avenues for input. This contrasts sharply with [48] study of Peru’s public sector, where telework models increased employee involvement through digital platforms. While JEDCO’s labor-intensive operations limit telework adoption, hybrid forums (e.g., digital suggestion boxes) could replicate [48] “human-centric” approach, fostering inclusivity in hierarchical settings.

- Training: This variable received the lowest average rating at (M = 3.22), as seen in Table 4. This aligns with JEDCO’s recognition that its training programs have become outdated and require immediate rejuvenation to be effective in today’s technological climate [15]. JEDCO’s training programs scored lowest among HRM practices (M = 3.22), reflecting a reactive approach to skill development. This contrasts with [16] systematic review, which advocates for “lifelong learning frameworks” integrating environmental sustainability (e.g., smart grid training). Aligning JEDCO’s programs with renewable energy upskilling, as suggested by [16], would advance SDG 8 (decent work) while preparing employees for Jordan’s energy transition.

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

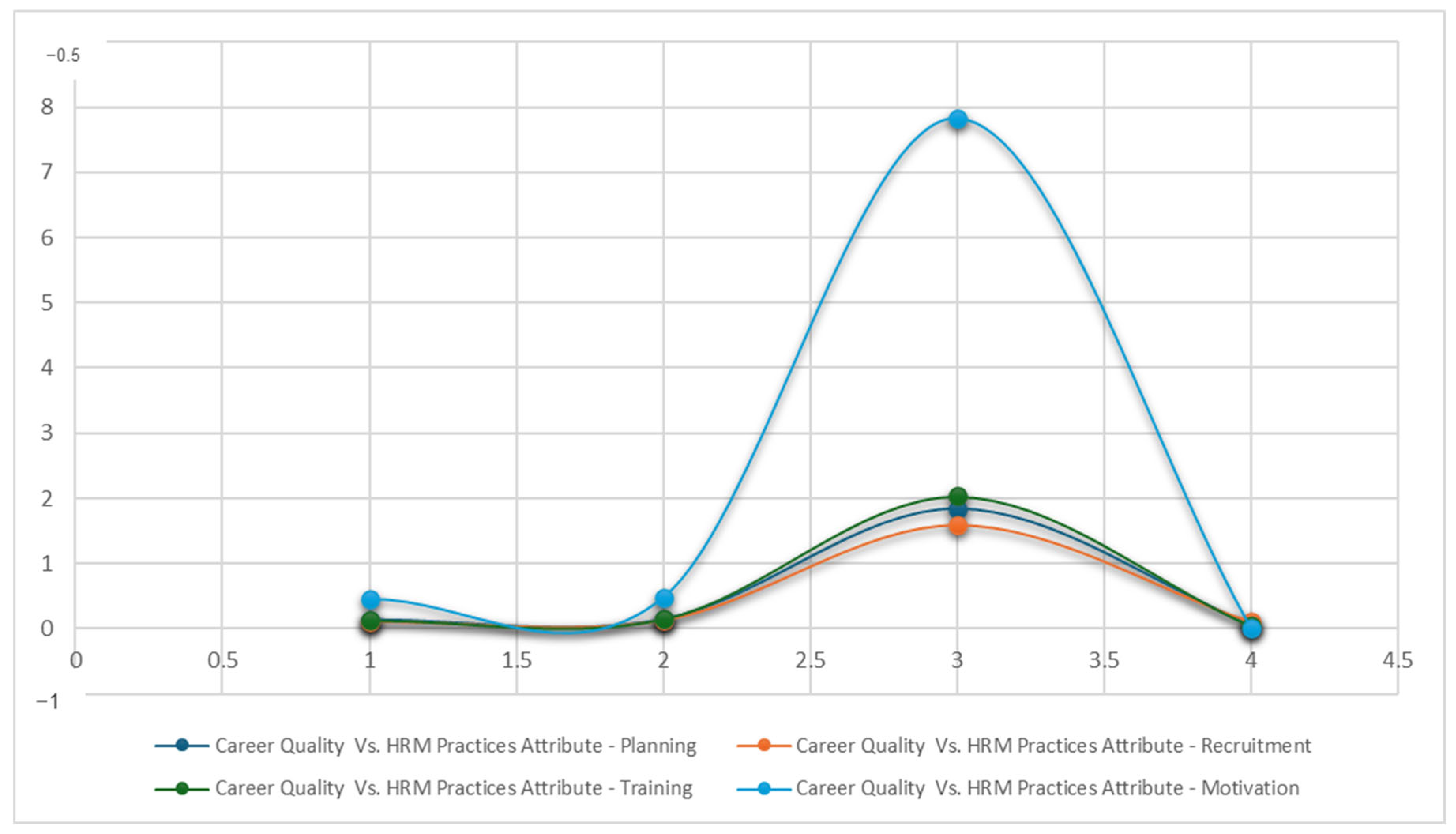

- Significant Impact of Training: The analysis indicates a statistically significant positive impact of training on career quality (β = 0.15, p = 0.044). The importance of training lies in its ability to enhance the skills and competencies of employees, positioning them for better career advancement and job satisfaction, thereby aligning with [29], who reported that upskilling significantly reduced turnover rates in their analysis.

- Strong Influence of Motivation: The results underscore that motivation is a critical determinant of career quality (β = 0.48, p < 0.001). This suggests that recognition and opportunities for professional development resonate profoundly with employees, promoting higher levels of engagement and loyalty—supporting the theories outlined in [25] self-determination theory. Employees who perceive their organization as supportive tend to exhibit stronger commitment, inspiring a collaborative atmosphere conducive to innovative decision-making.

- Marginally Significant Role of Planning: Planning was found to have a marginally significant impact on career quality (β = 0.15, p = 0.067), hinting at the importance of proactive workforce strategies that align with organizational needs. This finding reflects the constraints faced by JEDCO, particularly regarding its human resources planning processes, which have lacked robustness in addressing the organization’s long-term skill requirements.

- Non-Significant Effect of Recruitment: Conversely, recruitment showed no statistically significant effect on career quality, with β = 0.14 and a t-value of 1.59. This outcome might reflect biases embedded within recruitment processes at JEDCO, corroborated by previous assertions regarding the reliance on personal networks rather than merit-based evaluations [8].

5. Discussion

5.1. Thematic Discussion

5.1.1. Training as a Driver of Career Quality

5.1.2. Motivation and Social Exchange Dynamics

5.1.3. Recruitment and Planning: Systemic Challenges

5.2. Key Findings for Career Quality

5.2.1. Training and Motivation as Pillars of Career Quality

5.2.2. Recruitment and Planning: Systemic Weaknesses

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Theoretical Implications

5.4.1. Validation of Social Exchange Theory (SET)

5.4.2. Divergence from Western Models

6. Conclusions

6.1. Actionable Recommendations for JEDCO

- Digital HR Analytics Dashboard: JEDCO should implement a digital HR analytics dashboard to facilitate real-time workforce planning and data-driven decision-making. This tool should provide features for skill gap analysis and turnover risk metrics, utilizing predictive analytics to ensure that HR planning aligns with national energy transition targets and that training efforts meet workforce needs effectively.

- Biannual Motivation Index: Establishing a biannual Motivation Index will enable JEDCO to systematically measure employee engagement over time. This index should include key metrics related to intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, such as employee autonomy, salary satisfaction, and transparency in promotion criteria. Quarterly pulse surveys can be used to gather insights into employee perceptions and inform targeted motivation strategies.

- Innovative Recruitment Strategies: JEDCO should revamp its recruitment process by incorporating AI-driven tools to anonymize applications and reduce biases in hiring decisions. Collaborating with platforms like LinkedIn Talent Insights can assist in developing competency frameworks that ensure new hires are well-suited to the organization’s evolving needs. Furthermore, introducing gamified training modules in partnership with educational organizations can enhance engagement and learning effectiveness. Ref. [85] advocate for AI-driven anonymized recruitment in hierarchical public sectors, a strategy piloted successfully in Egypt’s EEHC. JEDCO could replicate this approach to mitigate tribal biases, aligning hiring with SDG 8 equity targets. To operationalize “AI-driven recruitment”, JEDCO’s Aqaba region will pilot anonymized hiring in 2024. Pre- and post-intervention retention rates will be measured quarterly (baseline: 63% retention in 2023), with targets to reduce tribal bias by 25% (p < 0.05 via t-test). Given the non-significance of recruitment practices (β = 0.14, p = 0.11), we propose AI-driven anonymized screening [24] to disrupt tribal favoritism.

- Structured Mentorship Initiatives: Management must emphasize career development through comprehensive mentorship programs that align individual aspirations with organizational goals. By fostering a culture of continuous support and development, JEDCO can enhance employee satisfaction and retention.

- Proactive Training Solutions: The HR department should prioritize the establishment of structured recruitment processes that emphasize merit-based assessments over personal biases. Additionally, proactive training solutions that focus on continuous learning will prepare employees for future challenges and enhance workforce efficacy. Gamified training modules (e.g., renewable energy simulations) will be assessed using pre/post-test scores (target: 20% skill improvement; α = 0.05). Develop VR simulations for smart grid troubleshooting, replicating [29] success in upskilling technicians.

- Employee Involvement in Career Development: Employees are encouraged to take an active role in their career development by providing constructive feedback to management regarding their experiences and aspirations. Participation in online learning platforms for certifications in emerging technologies, such as renewable energy, can further facilitate personal growth and competency enhancement.

- Resource Allocation for HR Development: Senior leadership and the board should advocate for resource allocation towards strengthening HR practices and career development initiatives, recognizing their critical role in JEDCO’s success. Developing comprehensive motivational strategies to effectively acknowledge and reward employee contributions is also essential.

- Engagement with Investors and Stakeholders: Investors and stakeholders should remain vigilant about the ongoing improvements needed in HR practices, encouraging management to adopt effective strategies that enhance career quality and organizational performance. Acknowledging the benefits of investing in employee development can yield sustainable growth and improved operational efficiency, solidifying JEDCO’s position in the market.

- Communication with Customers and the Public: Finally, it is important to educate customers and the public about how enhancements in HRM practices can lead to improved service reliability. Informing the community about the connections between effective HRM and customer satisfaction reinforces JEDCO’s commitment to serving both its customers and the wider community.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

6.3. Sustainability and SDG Alignment

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guest, D.E. Human Resource Management and Employee Well-Being: Towards a New Analytic Framework. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2017, 27, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfawaire, F.; Atan, T. The Effect of Strategic Human Resource and Knowledge Management on Sustainable Competitive Advantages at Jordanian Universities: The Mediating Role of Organizational Innovation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qudah, M.K.M.; Osma, A.; Halim, M.S.A.H.; Al-Shatnawi, O.M. The Effect of Human Resources Planning and Training and Development on Organizational Performance in the Government Sector in Jordan. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2014, 4, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najdat, M. The Impact of Human Resources Planning in Achieving the Effectiveness of the Recruitment Process Used at The King Abdullah University Hospital, M.A.; Jedara University: Irbid, Jordan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Jordan Economic Monitor: Strengthening Human Capital for a Competitive Economy; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Tracking SDG 7: The Energy Progress Report. A Joint Report of the Custodian Agencies: IEA, IRENA, UN, World Bank, and WHO, 2024; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dessler, G. A Framework for Human Resource Management; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Samarin, I.A.; Al-Asfour, A.A. National Human Resource Development in Transitioning Societies: The Case of Saudi Arabia. New Horiz. Adult Educ. Hum. Resour. Dev. 2023, 35, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhwar, P.; Pereira, V.; Mellahi, K.; Singh, S.K. The state of HRM in the Middle East: Challenges and future research agenda. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2019, 36, 905–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsardi, B. Jordan Energy Demand Forecast Using ARIMA Model Until 2030. Jordan J. Mech. Ind. Eng. 2024, 18, 471–483. Available online: https://jjmie.hu.edu.jo/vol18/vol18-3/03-JJMIE-228-24.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Emidy, M.B.; Lewis, G.B.; Pizarro-Bore, X.U.S. Federal Employees with Disabilities: How Perceptions of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility Affect Differences in Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment, and Job Involvement. Public Pers. Manag. 2024, 53, 649–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. Living and Working in Europe 2022; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Panjaitan, E.H.H.; Rupianti, R.; Sukomardojo, T.; Astuti, A.R.T.; Sutardjo, A. The Role of Human Resource Management, in Improving Employee Performance in Private Companies. Panjaitan 2023, 4, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koman, G.; Boršoš, P.; Kubina, M. The Possibilities of Using Artificial Intelligence as a Key Technology in the Current Employee Recruitment Process. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mzary, M.M.; Al-rifai, A.D.A.; Al-Momany, M.O.E. Training and its Impact on the Performance of Employees at Jordanian Universities from the Perspective of Employees: The Case of Yarmouk University. J. Educ. Pract. 2015, 6, 128–140. Available online: https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JEP/article/view/27295 (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Madero-Gómez, S.M.; Rubio Leal, Y.L.; Olivas-Luján, M.; Yusliza, M.Y. Companies Could Benefit When They Focus on Employee Wellbeing and the Environment: A Systematic Review of Sustainable Human Resource Management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Workforce Transitions in Arab Energy Sectors: Aligning HRM with SDG 8; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Aust, I.; Matthews, B.; Muller-Camen, M. Common Good HRM: A Paradigm Shift in Sustainable HRM? Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normala, D. Investigating the Relationship between Quality of Work Life and Organizational Commitment Amongst Employees in Malysian firm. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 5, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gulan, X.-Z.M.; Aguiling, H. Examining the Role of Organizational Climate on Career Adaptability and Government Employees’ Career Intention. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. (2147–4478) 2022, 10, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Anthony, E.L.; Daniels, S.R.; Hall, A.V. Social Exchange Theory: A critical Review with Theoretical Remedies. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2023, 11, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, F.; Wei, L.; Bányai, T.; Nurunnabi, M.; Subhan, Q.A. An Examination of Sustainable HRM Practices on Job Performance: An Application of Training as a Moderator. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horodyski, P. Applicants’ Perception of Artificial Intelligence in the Recruitment Process. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2023, 11, 100303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination Theory: A Macrotheory of Human Motivation, Development, and Health. Can. Psychol./Psychol. Can. 2008, 49, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Jordan. Jordan Energy Strategy Action Plan 2020–2030, 2nd ed.; Ministry of Planning: Amman, Jordan, 2022. Available online: https://www.memr.gov.jo/EBV4.0/Root_Storage/EN/EB_Info_Page/Second_edition_-_JES_action_plan.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Iles, P.; Almhedie, A.; Baruch, Y. Managing HR in the Middle East: Challenges in the Public Sector. Public Pers. Manag. 2012, 41, 465–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, D.L.; Deadrick, D.L.; Lukaszewski, K.M. The influence of Technology on the Future of Human Resources Management. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2023, 25, 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hečko, Š.; Řihák, R.; Malátek, V. Lifelong Learning as Form of Human Resources Development. Eduk. Ekon. I Menedżerów 2014, 33, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesário, F.; Sabino, A.; Palma-Moreira, A.; Pinto-Coelho, M. Exploring Links Between Green HRM, Greenwashing, and Sustainability: The Role of Individual and Professional Traits. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabino, A.; Moreira, A.; Cesário, F.; Pinto Coelho, M. Measuring Sustainability: A Validation Study of a Triple Bottom Line (TBL) Scale in Portugal. Emerg. Sci. J. 2024, 8, 899–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Sheikha, N. Human Resources Management—Theoretical Framework and Practical Cases; Dar Safaa for Publishing and Distribution: Amman, Jordan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shawish, M.N. Human Resources Department; Al Shorouk Publishing and Distribution House: Amman, Jordan, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Salih, A.A. Strategic Human Resources Management: Strategies in Iraq and Jordan. In Strategic Thinking, Planning, and Management Practice in the Arab World; Albadri, F., Nasereddin, Y., Eds.; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 112–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Work-Related Flow in Career Sustainability. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemat, M.M. Personnel Management; Innovation Publishing and Distribution House: Amman, Jordan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Omer, F.A.Y.; Arumugam, T.A.L. Role of Human Resource Planning in Improving the Quality of Health Care Centers’ Services (An Analytical Study of Health Care Centers in the Eastern Province of Kingdom of Saudi Arabia). Int. J. Res. Stud. Publ. 2025, 6, 348–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santinha, G.; Carvalho, T.; Forte, T.; Fernandes, A.; Tavares, J. Profiling Public Sector Choice: Perceptions and Motivational Determinants at the Pre-Entry Level. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmuti, D.; Grunewald, J.; Abebe, D. Consequences of Outsourcing Strategies on Employee Quality of Work Life, Attitudes, and Performance. J. Bus. Strateg. 2010, 27, 177–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrayyan, M.T.; Al-Faouri, I. Predictors of Career Commitment and Job Performance of Jordanian Nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2008, 16, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, M. Armstrong’s Handbook of Human Resource Management Practice, 12th ed.; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hanafi, A.G. Organizational Behavior and Human Resources Management; New University Publishing House: Alexandria, Egypt, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S.E.; Schuler, R.S. Understanding Human Resource Management in the Context of Organizations and their Environments. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1995, 46, 237–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilalli Abduraimi, P.; Mustafi, M.; Islami, X. The role of Organizational Culture on Employee Engagement. Bus. Theory Pract. 2023, 24, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.L.; Tashakkori, A. Decision Participation and School Climate as Predictors of Job Satisfaction and Teachers’ Sense of Efficacy. J. Exp. Educ. 1995, 63, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diop, A. Empowering Employees as an Entry Point for Improving the Quality of Career in the Syrian Telecommunications Sector (Field Study), Damascus University. J. Econ. Leg. Sci. 2014, 30, 195–224. [Google Scholar]

- Ba’era, A. Management Principles: Concepts and Applications, I6; Dar Al-Fadhil: Benghazi, Libya, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ríos Villacorta, M.A.; Ramos Farroñán, E.V.; Arbulú Ballesteros, M.A.; Otiniano León, M.Y.; Bravo Jaico, J.L.; Suysuy Chambergo, E.J.; Reyes-Pérez, M.D.; Ganoza-Ubillús, L.M.; Alarcón García, R.E. Human-Centric Telework and Sustainable Well-Being: Evidence from Peru’s Public Sector. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, B.A.H.; Anayyed, H.B. Impact of Comprehensive Quality Management on the Quality of Working Life: An Analytical Study of the vVews of a Sample of Employees of the Maysan Oil Company. J. Sustain. Stud. 2021, 3, 446–474. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Anzi, S.; Al-Saadi, M. Philosophy of Human Resources Strategy. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2007, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Cadin, L. Francis Guérin et Frédérique Pigeyre, Gestion des Ressources Humaines; Pratique et Éléments de Théorie: Dunod, Paris, 1997; 323p. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, O.; Temtime, Z. Recruitment and Selection Practices in SMEs: Empirical Evidence from a Developing Country Perspective. Adv. Manag. 2010, 3, 52–78. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shawabkeh, K.M.; Hijjawi, G.S. Impact of Quality of Work-life (QWL) on Organizational Performance: An empirical Study in the Private Jordanian Universities. Asian Soc. Sci. 2018, 14, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawari, S.; Hawari, S. Impact of Human Resources Management Strategies on Job Satisfaction of the Employees of the Social Security Corporation in Jordan. Glob. J. Manag. Bus. Res. 2017, 17, 37–46. Available online: https://journalofbusiness.org/index.php/GJMBR/article/view/2246 (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Kambur, E.; Yildirim, T. From Traditional to Smart Human Resources Management. Int. J. Manpow. 2023, 44, 422–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abunaila, A.S.H.; Kadhim, S.M. Improve the Competitive Advantage Through Human Resources Management Practices in the Iraqi Banking Sector. Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 2022, 7, e0891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khameeli, F. Changes in the Internal Environment have Affected the Carefully Employed Human Resources of the Farmal Branch Fishing Complex. Kufa Stud. Cent. J. 2014, 1, 143–167. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Zahrani, A. Training Strategy and its Impact on the Behavioral Merits of Employees of Saudi Commercial Banks. Jordanian J. Bus. Adm. 2012, 8, 707–735. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, R.R.; Gardênia Abbad, G. Training Needs Assessment: Where we are and where we should go. BAR Braz. Adm. Rev. 2013, 10, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbancová, H.; Vrabcová, P.; Hudáková, M.; Petrů, G.J. Effective Training Evaluation: The Role of Factors Influencing the Evaluation of Effectiveness of Employee Training and Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, M. Evaluation of Training and Return on Training Investment, Conference Consulting and Training in Arab Institutions; Arab Organization for Administrative Development: Cairo, Egypt, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Taani, H. Contemporary Management Training; Al-Serrah Publishing and Distribution House: Amman, Jordan, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul Bari, D.; Al-Sabbagh, Z. Human Resources Department Menah Nazmi, 1st ed.; Wael Publishing House: Amman, Jordan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Abu Al-Nasr, M. Management of Training Operations: Theory and Application; Dar al-Fajr: Cairo, Egypt, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Akili, O. Strategic Human Resource Management: Strategic Dimension; Dar Wael Publishing and Distribution: Amman, Jordan, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, S.; Bashir, M.; Bureš, V.; Zanker, M.; Ullah, S.; Rizwan, A. Impact of knowledge sharing and innovation on performance of organization: Evidence from the pharmaceutical industry of Pakistan. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2471536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sirfi, M. Personnel Management and Human Relations, 1st ed.; Dar Qandil: Amman, Jordan, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zweilev, M. Managing Individuals in a Quantitative Perspective and Human Relations; Think Tank for Printing and Publishing: Amman, Jordan, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Alkandi, I.G.; Khan, M.A.; Fallatah, M.; Alabdulhadi, A.; Alanizan, S.; Alharbi, J. The Impact of Incentive and Reward Systems on Employee Performance in the Saudi Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Industrial Sectors: A Mediating Influence of Employee Job Satisfaction. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrus, N.I.; Hashim, N.; Rahman, N.L.A.; Pisal, N.A. The Impact of Employees’ Motivation Factors toward Job Satisfaction. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2022, 12, 660–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawad Latif, K. An Integrated Model of Training Effectiveness and Satisfaction with Employee Development Interventions. Ind. Commer. Train. 2012, 44, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A. Human Resources Department Contemporary Vision, I1; University House: Cairo, Egypt, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rabia, Z. The Effectiveness of Guarantees and Incentive Regulations to Encourage Investment in Algerian Legislation. J. Law Sustain. Dev. 2024, 12, e3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, Y. The Impact of Incentives on Job Performance, Business Cycle, and Population Health in Emerging Economies. Front. Public Health 2022, 9, 778101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, Z. Cross-Sectional Studies: Strengths, Weaknesses, and Recommendations. Chest 2020, 158, S65–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2015, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch, Y.; Holtom, B.C. Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Hum. Relat. 2008, 61, 1139–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkin, T.R. A Brief Tutorial on the Development of Measures for Use in Survey Questionnaires. Organ. Res. Methods 1998, 1, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, J. Do Data Characteristics Change According to the Number of Scale Points Used? An Experiment Using 5-Point, 7-Point and 10-Point Scales. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 50, 61–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common MethodBiases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmanesh, P.; Mostepaniuk, A.; Khoshkar, P.G.; Alhamdan, R. Fostering Employees’ Job Performance through Sustainable Human Resources Management and Trust in Leaders—A Mediation Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri, R.; El-Metwally, A.; Sallinen, M.; Pöyry, M.; Härmä, M.; Toppinen-Tanner, S. The Role of Continuing Professional Training or Development in Maintaining Current Employment: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ouabi, Z.; Douayri, K.; Barboucha, F.; Boubker, O. Human Resource Practices and Job Performance: Insights from Public Administration. Societies 2024, 14, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labsis, E.; Khatash, R. The Reality of the Application of Modern Practices of Human Resources Management and its Relationship to the Quality of Working Life in Algerian Institutions, Field Study of the Electricity and Renewable Energies Company—Pairing—Algeria. J. Res. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2018, 34, 135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Hoxha, G.; Simeli, I.; Theocharis, D.; Vasileiou, A.; Tsekouropoulos, G. Sustainable Healthcare Quality and Job Satisfaction through Organizational Culture: Approaches and Outcomes. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Definition | Measurement | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent | Career Quality | Employee perceptions of job security, promotion equity, and participatory decision-making. | 10-item 5-point Likert scale [11] |

| Independent | Planning | Strategic alignment of workforce needs with organizational goals. | 9-item 5-point Likert scale [49] |

| Recruitment | Fairness and transparency in hiring processes. | 8-item 5-point Likert scale [52] | |

| Training | Effectiveness of skill development programs. | 6-item 5-point Likert scale [58] | |

| Motivation | Intrinsic and extrinsic incentives influencing performance. | 8-item 5-point Likert scale [25] | |

| Construct | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE | HTMT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Career Quality | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.62 | 0.79 |

| Planning | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.60 | 0.80 |

| Recruitment | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.58 | 0.82 |

| Training | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.57 | 0.83 |

| Motivation | 0.88/0.90 | 0.90 | 0.59 | 0.81 |

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 161 | 93.1% |

| Female | 12 | 6.9% | |

| Experience | <5 Years | 17 | 9.8% |

| 5–10 Years | 44 | 25.4% | |

| 10–15 Years | 44 | 25.4% | |

| >15 Years | 68 | 39.3% | |

| Education | Higher Education | 13 | 7.5% |

| Undergraduate | 86 | 49.7% | |

| Diploma | 29 | 16.8% | |

| Secondary School | 45 | 26.0% | |

| Job Role | Manager | 21 | 12.1% |

| Head Department | 34 | 19.7% | |

| Engineer | 21 | 12.1% | |

| Administrative | 37 | 21.4% | |

| Technician | 60 | 34.7% |

| Variable | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Career Quality | 3.36 | 0.73 | −0.39 | −0.07 |

| Planning | 3.39 | 0.80 | −0.59 | 0.66 |

| Recruitment | 3.26 | 0.84 | −0.49 | 0.07 |

| Training | 3.22 | 0.85 | −0.23 | −0.26 |

| Motivation | 3.34 | 0.78 | −0.53 | 0.25 |

| Variable | B | SE | Β | T | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.56 | 0.15 | – | 3.79 | 0.00 |

| Planning | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 1.84 | 0.07 |

| Recruitment | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 1.59 | 0.11 |

| Training | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 2.03 | 0.04 |

| Motivation | 0.45 | 0.06 | 0.48 | 7.83 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Oun, S.; Al-Khasawneh, Z. Sustainable Human Resource Management and Career Quality in Public Utilities: Evidence from Jordan’s Electricity Sector. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4866. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114866

Al-Oun S, Al-Khasawneh Z. Sustainable Human Resource Management and Career Quality in Public Utilities: Evidence from Jordan’s Electricity Sector. Sustainability. 2025; 17(11):4866. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114866

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Oun, Salem, and Ziad (Mohammed Fa’eq) Al-Khasawneh. 2025. "Sustainable Human Resource Management and Career Quality in Public Utilities: Evidence from Jordan’s Electricity Sector" Sustainability 17, no. 11: 4866. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114866

APA StyleAl-Oun, S., & Al-Khasawneh, Z. (2025). Sustainable Human Resource Management and Career Quality in Public Utilities: Evidence from Jordan’s Electricity Sector. Sustainability, 17(11), 4866. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114866