Empowering Culture and Education Through Digital Content Creation, Preservation, and Dissemination

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. History of the Digitization of Library Resources

2.1. Evolution—From Microfilms to Digital Libraries

2.2. Technical Aspects—The Evolution of Algorithms, Techniques, and Interoperability

- the presence of a web interface for downloading or directly viewing content; or

- the integration of specialized services providing the access interface and devices and applications for the end-user (such as Libby [17] from OverDrive).

3. Models of Digital Libraries

3.1. Global Level

3.1.1. Google Books

3.1.2. Europeana

3.2. National Level

3.2.1. National Library of Norway

3.2.2. Dutch National Library

3.2.3. Digital Public Library of America (DPLA)

3.3. Shadow Libraries

3.3.1. Sci-Hub

3.3.2. Libgen

3.3.3. Monoskop

4. Case Study: Digitization in Romania

4.1. Normative Aspects and Statistics

4.2. Project Examples

4.2.1. Digital Library of Bucharest (Former Dacoromanica)

4.2.2. Memoria.ro

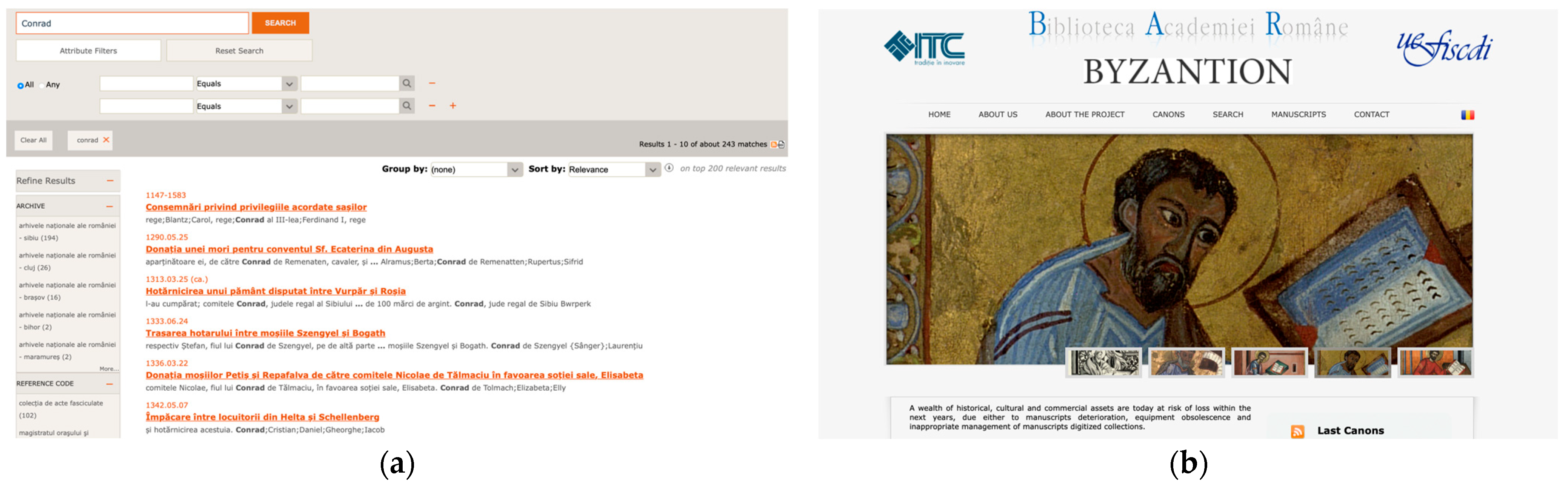

4.2.3. Medievalia

4.2.4. Byzantion Project

4.2.5. Lib2Life

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Devi, T.S.; Murthy, T.A.V. The need for digitization. In Digital Information Resources & Networks on India: Essays in Honor of Professor Jagindar Singh Ramdev on his 75th Birthday; UBS Publishers’ Distributors Pvt. Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Coppi, D.; Grana, C.; Cucchiara, R. Illustrations Segmentation in Digitized Documents Using Local Correlation Features. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2014, 38, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisostomo, C. Digitizing Documents: Why, How, and Where. 2015. Available online: https://blog.kamiapp.com/digitizing-documents-why-how-and-where/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Talbot, D. Impact of Book Publishing on Environment—WordsRated. 2023. Available online: https://wordsrated.com/impact-of-book-publishing-on-environment/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Suhler, R. Printed Books or Digital Books—Which are More Environmentally Friendly? 2023. Available online: https://davidson.weizmann.ac.il/en/online/sciencepanorama/wake-green-books (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Kae, A.; Learned-Miller, E. Learning on the Fly: Font-Free Approaches to Difficult OCR Problems. In Proceedings of the 2009 10th International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Barcelona, Spain, 26–29 July 2009; pp. 571–575. [Google Scholar]

- Deegan, M.; Tanner, S. Digital Futures: Strategies for the Information Age; Neal-Schuman Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt, R.; Otlet, P. Sur une Forme Nouvelle du Livre: Le Livre Microphotographique; Bruxelles Institut International de Bibliographie: Mons, Belgium, 1906. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, A. Cataloging the World: Paul Otlet and the Birth of the Information Age; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 200–225. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, V. As We May Think. Atl. Mon. 1945, 176, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Licklider, J.C.R. Libraries of the Future; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Cornell University. ArXiv, Archives. Available online: https://arxiv.org/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- NDLTD. Theses and Dissertations. Available online: http://www.ndltd.org/ (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Minerva; European Commission. Minerva Europe Knowledge Base—MInisterial NEtwoRk for Valorising Activities in digitisation, eContent-plus—Supporting the European Digital Library. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/IST-2001-35461 (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- IFLA. Library Associations and International Council on Archives, Guidelines for Digitization Projects for Collections and Holdings in the Public Domain, Particularly Those Held by Libraries and Archives; IFLA Preservation and Conservation Section: Washington, WA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Content Conversion Specialists (CCS). docWorks. Available online: https://content-conversion.com/ (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Overdrive Inc. Libby App. Available online: https://www.overdrive.com/apps/libby/ (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Brown, A. Archives Outside. Available online: https://archivesoutside.records.nsw.gov.au/author/anthea/page/3/ (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Peak, G. Methods of Digitisation. Available online: https://glampeak.org.au/toolkit/digitise/methods/ (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- University of Notre Dame, Center for Digital Scholarship. Available online: https://cds.library.nd.edu/ (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- National Transportation Library. Digitization: Metadata Standards. Available online: https://transportation.libguides.com/ (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Boock, M. Organizing for Digitization at Oregon State University: A Case Study and Comparison with ARL Libraries. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2008, 34, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Content Conversion Specialists (CCS). METAe. Available online: https://old.diglib.org/forums/spring2005/presentations/CCS-2005-04.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Barbero, B.R.; Ureta, E.S. Comparative Study of Different Digitization Techniques and Their Accuracy. Comput. Des. 2011, 43, 188–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bountouri, L. Archives in the Digital Age: Standards, Policies and Tools; Chandos Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.Q.; Li, L. Emerging Technologies for Librarians: A Practical Approach to Innovation; Chandos Publishing: Waltham, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Greenstone. About Greenstone. Greenstone Digital Library Software. Available online: http://www.greenstone.org/ (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- University of Salfor Manchester. Aletheia Document Analysis System; PRImA—Pattern Recognition & Image Analysis Research Lab. Available online: https://www.primaresearch.org/ (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Github Repositor. Ocropus/Ocropy. 2016. Available online: https://github.com/tmbarchive/ocropy (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Github Repository. CLSTM Neural Network. 2016. Available online: https://github.com/tmbdev/clstm (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. Guidelines for Planning the Digitization of Rare Book and Manuscript Collections. 2014. Available online: http://www.ifla.org/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Lefevere, F.-M.; Saric, M. Detection of Grooves in Scanned Images. United States Patent US7508978B1, 24 March 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Somers, J. Torching the Modern-Day Library of Alexandria. The Atlantic, 20 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Heyman, S. Google Books: A Complex and Controversial Experiment. The New York Times, 28 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, K. The Artful Accidents of Google Books. The New Yorker, 4 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, M.; Price, G. Update: Association of American Publishers and Google Announce Settlement Agreement. Infodocket, 4 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- BBC News. Authors Sue Google over Book Plan. BBC News, 21 September 2005.

- The Guardian. Google Books Wins Case Against Authors over Putting Works Online. The Guardian News, 14 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Europeana. Europeana Official Website. Available online: https://www.europeana.eu/en (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Europeana. Europeana Process. Available online: https://pro.europeana.eu/share-your-data/process (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Europeana. Europeana Mission. Available online: https://pro.europeana.eu/about-us/mission (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Official Github. Europeana. Available online: https://github.com/europeana/ (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Europeana Newspapers. Europeana Newspapers Is Making Historic Newspaper Pages Searchable. 2018. Available online: http://www.europeana-newspapers.eu/ (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Stiller, J.; Petras, V. Learning from Digital Library Evaluations: The Europeana Case. ABI Tech. 2018, 38, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suciu, M.-C.; Fanea-Ivanovici, M. The European digital library (Europeana). Concerns related to intellectual property rights. Jurid. Trib. Buchar. Acad. Econ. Stud. Law Dep. 2018, 8, 244–259. [Google Scholar]

- Tallova, L. Copyright Aspects of Disclosure of Works within the Europeana Digital Library. In Proceedings of the SGEM 2014 Scientific SubConference on Political Sciences, Lawn Finance, Economics and Tourism, Albena, Bulgaria, 1–10 September 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanian Digital Library (Romanian Biblioteca Digitală Națională), Collections. 2007. Available online: http://digitool.bibnat.ro/R (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- National Library of Norway. Digitizing at the National Library. Available online: https://www.nb.no/en/digitizing-at-the-national-library/ (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- National Library of Norway. The Collection. Available online: https://www.nb.no/en/the-collection/ (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- National Library of Norway. CENL—Norway Annual Report 2013. Available online: https://www.cenl.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/CENL_2013_Report_Norway.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Janssen, O.D. Digitizing All Dutch Books, Newspapers and Magazines—730 Million Pages in 20 Years—Storing It, and Getting It Out There. In Research and Advanced Technology for Digital Libraries; National Library of the Netherlands, Berlin, Part of Lecture Notes in Computer Science Book Series—LNCS 6966; Koninklijke Bibliotheek, K.B., Ed.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 473–476. [Google Scholar]

- National Library of the Netherlands. Digital Resources. Available online: https://www.kb.nl/en/digital-resources (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Carr, N. The Library of Utopia. MIT Technology Review. 25 April 2012. Available online: https://www.technologyreview.com/2012/04/25/116142/the-library-of-utopia/ (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Digital Public Library of America. Digital Library Digest: Friday the 13th Edition. Available online: https://dp.la/news/digital-library-digest-friday-the-13th-edition (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Karaganis, J. Shadow Libraries. Access to Knowledge in Global Higher Education; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield, B. What Is a Shadow Library? BuiltIn. 9 October 2024. Available online: https://builtin.com/articles/shadow-library (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Bohannon, J. The Frustrated Science Student Behind Sci-Hub. Science 2016, 352, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engineuring. Sci-Hub and Alexandra Basic Information. 2019. Available online: https://engineuring.wordpress.com/2019/03/31/sci-hub-and-alexandra-basic-information/ (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Cabanac, G. Bibliogifts in LibGen? A study of a text-sharing platform driven by biblioleaks and crowdsourcing. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 874–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monoskop, About Monoskop. Available online: https://monoskop.org/About_Monoskop (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Thylstrup, N.B. The Politics of Mass Digitization; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; p. 216. [Google Scholar]

- Romanian Ministry of Culture (RO, Ministerul Culturii și Cultelor). Order No. 2244/15.04.2008 Related to the Creation of Specialised Commissions for the Digitisation of the National Cultural Resources and the Creation of the Digital Library of Romania; Romanian Ministry of Culture: Bucharest, Romania, 2008.

- Romanian Government. Decision 1676 from 10/12/2008 for the Approval of the National Program for the Digitisation of the National Cultural Resources and the Creation of the Digital Library of Romania; Romanian Government: Bucharest, Romania, 2008.

- Official Journal of the European Union. Commission Recommendation of 24 August 2006 on the Digitisation and Online Accessibility of Cultural Material and Digital Preservation; Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Official Journal of the European Union. Information and Notices; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2006; Volume 49. [Google Scholar]

- Official Journal of the European Union. Commission Recommendation of 27 October 2011 on the Digitisation and Online Accessibility of Cultural Material and Digital Preservation; Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Birla, D. Romania Still Has a Long Way to Go Before Libraries Are Digitized. “It’s a Fairly Extensive Process”. ProTV News. 23 October 2023. Available online: https://stirileprotv.ro/stiri/actualitate/romania-mai-are-de-asteptat-pana-la-digitalizarea-bibliotecilor-zeste-un-proces-destul-de-amplu.html (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Neagoe, O. The Digital Book Market Will Reach 50 Million Lei in the Next Three Years. Revista Biz. 4 April 2023. Available online: https://www.revistabiz.ro/piata-de-carte-digitala-va-ajunge-la-50-de-milioane-de-lei-in-urmatorii-trei-ani/ (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Șerbănescu, I. Dacoromanica Digital Library of Romania. Slideplayer Presentation. 2010. Available online: https://www.slideserve.com/shika/dacoromanica (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Cristian, M.F. Bucharest Digital Library. DC News. 2018. Available online: https://www.dcnews.ro/biblioteca-digitala-a-bucurestilor-din-nou-online_575919.html (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- The Aspera Foundation. Memoria.ro—About the Website. Available online: http://www.memoria.ro/despre_noi/despre_site/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Romanian Academy. Workshop Heritage Collections in the Digital Age, 2nd Edition—Byzantion Project Realized by the Library of the Romanian Academy. Online Journal of the Romanian Academy. 2016. Available online: https://academiaromana.wordpress.com/2016/12/04/workshopul-colectiile-de-patrimoniu-in-era-digitala-editia-a-ii-a-proiectul-byzantion-realizat-de-biblioteca-academiei-romane/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Moga, H. Byzantion—About the Project. 2020. Available online: http://byzantion.itc.ro/proiect (accessed on 15 December 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stănică, I.-C.; Boiangiu, C.-A.; Tăut, C. Empowering Culture and Education Through Digital Content Creation, Preservation, and Dissemination. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4842. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114842

Stănică I-C, Boiangiu C-A, Tăut C. Empowering Culture and Education Through Digital Content Creation, Preservation, and Dissemination. Sustainability. 2025; 17(11):4842. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114842

Chicago/Turabian StyleStănică, Iulia-Cristina, Costin-Anton Boiangiu, and Codrin Tăut. 2025. "Empowering Culture and Education Through Digital Content Creation, Preservation, and Dissemination" Sustainability 17, no. 11: 4842. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114842

APA StyleStănică, I.-C., Boiangiu, C.-A., & Tăut, C. (2025). Empowering Culture and Education Through Digital Content Creation, Preservation, and Dissemination. Sustainability, 17(11), 4842. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114842