The Green Dilemma: The Impact of Inconsistent Green Human Resource Management and Innovation on Employees’ Creative Performance

Abstract

:1. Introduction

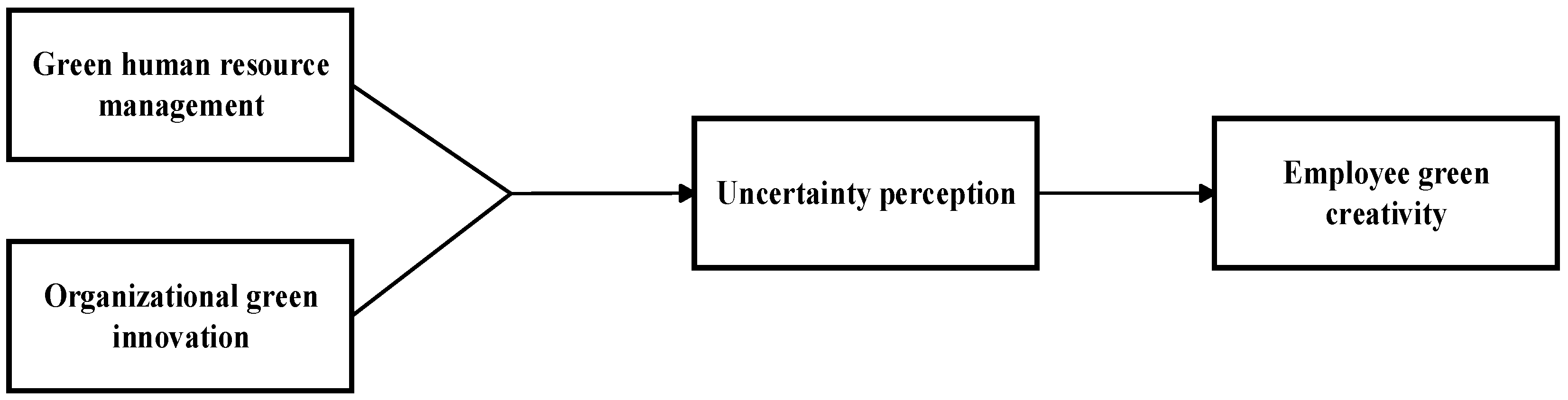

2. Theoretical Foundation

2.1. Cue Consistency Theory

2.2. Social Information Processing Theory

3. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

3.1. GHRM, OGI, and EGC

3.2. GHRM and OGI

3.3. The Mediating Role of Uncertainty Perception

4. Methodology

4.1. Participants

4.2. Measurement Instruments

4.2.1. GHRM

4.2.2. OGI

4.2.3. EGC

4.2.4. UP

4.3. Variable Data Processing Technology

5. Results

5.1. Common Method Deviation Test

5.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

| Model | χ2 | df | RMSEA | CFI | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-factor model: (GHRM, OGI, UP, EGC) | 861.986 | 224.00 | 0.083 | 0.883 | 0.047 |

| Three-factor model: (GHRM, OGI + UP, EGC) | 1057.765 | 227.000 | 0.094 | 0.847 | 0.053 |

| Two-factor model: (GHRM + OGI + UP, EGC) | 1065.648 | 229.000 | 0.094 | 0.846 | 0.054 |

| Single-factor model: (GHRM + OGI + UP + EGC) | 1091.633 | 230.000 | 0.054 | 0.841 | 0.054 |

5.3. Descriptive Statistical Results and Correlation Analysis

5.4. Path Analysis and Hypothesis Testing

5.5. Mediation Effect Test

6. Discussion and Conclusion

7. Implications

7.1. Theoretical Implications

7.2. Practical Implications

8. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kulkarni, S. Editorial: Global Sustainability: Trends, Challenges, and Case Studies. In Global Sustainability: Trends, Challenges & Case Studies; Kulkarni, S., Haghi, A.K., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, D.R.; Ribeiro, N.; Gomes, G.; Ortega, E.; Semedo, A. Green HRM’s Effect on Employees’ Eco-Friendly Behavior and Green Performance: A Study in the Portuguese Tourism Sector. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, A.H.; Umer, M.; Nauman, S.; Abbass, K.; Song, H. Sustainable development goals and green human resource management: A comprehensive review of environmental performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabokro, M.; Masud, M.M.; Kayedian, A. The effect of green human resources management on corporate social responsibility, green psychological climate and employees’ green behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Tang, G.; Jackson, S.E. Green human resource management research in emergence: A review and future directions. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2018, 35, 769–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Juan, H. Trends and trajectories in employee green behavior research. Front. Sociol. 2024, 9, 1486377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur, T.; Topaloglu, E.E.; Yilmaz-Ozekenci, S.; Koycu, E. The Impact of Energy Intensity, Renewable Energy, and Financial Development on Green Growth in OECD Countries: Fresh Evidence Under Environmental Policy Stringency. Energies 2025, 18, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafaei, A.; Nejati, M.; Yusoff, Y.M. Green human resource management. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 1041–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R. Green Human Resource Management and Employee Green Behavior: An Empirical Analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Ullah, K.; Khan, A. The impact of green HRM on green creativity: Mediating role of pro-environmental behaviors and moderating role of ethical leadership style. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 33, 3789–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualigah, A.; Koburtay, T.; Bourini, I.; Badar, K.; Gerged, A.M. Towards sustainable development in the hospitality sector: Does green human resource management stimulate green creativity? A moderated mediation model. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 3217–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muisyo, P.K.; Su, Q.; Hashmi, H.b.A.; Ho, T.H.; Julius, M.M. The role of green HRM in driving hotels’ green creativity. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 1331–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z.; Khosa, M.; Rehman, S.U.; Faqera, A.F.O. Towards sustainable development in the manufacturing industry: Does green human resource management facilitate green creative behaviour? A serial mediation model. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2023, 34, 1425–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, R.; Zhang, Z.; Talwar, S.; Dhir, A. Do green human resource management and self-efficacy facilitate green creativity? A study of luxury hotels and resorts. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 824–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheswaran, D.; Chaiken, S. Promoting systematic processing in low-motivation settings: Effect of incongruent information on processing and judgment. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. Cue-Consistency and Cue-Utilization in Judgment. Am. J. Psychol. 1966, 79, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V. Consistency Matters! How and When Does Corporate Social Responsibility Affect Employees’ Organizational Identification? J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 1141–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.H. Foundations of Information Integration Theory. Am. J. Psychol. 1982, 95, 708–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crucke, S.; Servaes, M.; Kluijtmans, T.; Mertens, S.; Schollaert, E. Linking environmentally-specific transformational leadership and employees’ green advocacy: The influence of leadership integrity. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, A.D.; Grewal, D.; Goodstein, R.C. The Effect of Multiple Extrinsic Cues on Quality Perceptions: A Matter of Consistency. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salancik, G.R.; Pfeffer, J. A Social Information Processing Approach to Job Attitudes and Task Design. Adm. Sci. Q. 1978, 23, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Paillé, P.; Jia, J. Green human resource management practices: Scale development and validity. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2018, 56, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, C.L.Z.; Dubois, D.A. Strategic HRM as social design for environmental sustainability in organization. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 51, 799–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, Z.; Naeem, R.M.; Hassan, M.; Naeem, M.; Nazim, M.; Maqbool, A. How GHRM is related to green creativity? A moderated mediation model of green transformational leadership and green perceived organizational support. Int. J. Manpow. 2022, 43, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, B.-K.; Hahn, H.-J.; Peterson, S.L. Turnover intention: The effects of core self-evaluations, proactive personality, perceived organizational support, developmental feedback, and job complexity. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2015, 18, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, M.; Rahman, S.M.M.; Biswas, S.; Szabó-Szentgróti, G.; Walter, V. Effects of green human resource management practices on employee green behavior: The role of employee’s environmental knowledge management and green self-efficacy for greening workplace. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Bhutto, T.A.; Xuhui, W.; Maitlo, Q.; Zafar, A.U.; Bhutto, N.A. Unlocking employees’ green creativity: The effects of green transformational leadership, green intrinsic, and extrinsic motivation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, A.; Farrukh, M.; Lee, J.-K.; Jahan, S. Stimulation of Employees’ Green Creativity through Green Transformational Leadership and Management Initiatives. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L.T. Fostering green product innovation through green entrepreneurial orientation: The roles of employee green creativity, green role identity, and organizational transactive memory system. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meir, E.I. Integrative elaboration of the congruence theory. J. Vocat. Behav. 1989, 35, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, Q.; Nadeem, M.S.; Raziq, M.M.; Sajjad, A. Linking individuals’ resources with (perceived) sustainable employability: Perspectives from conservation of resources and social information processing theory. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2022, 24, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischel, W.; Shoda, Y. A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: Reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychol. Rev. 1995, 102, 246–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyler, T.R.; Blader, S.L. Can Businesses Effectively Regulate Employee Conduct? The Antecedents of Rule Following in Work Settings. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 1143–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhao, S. Does HRM facilitate employee creativity and organizational innovation? A study of Chinese firms. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 4025–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamassian, P. Uncertain perceptual confidence. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2022, 6, 179–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weary, G.; Edwards, J.A. Individual Differences in Causal Uncertainty. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 67, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriksen, D.; Mishra, P.; the Deep-Play Research Group. Creativity, Uncertainty, and Beautiful Risks: A Conversation with Dr. Ronald Beghetto. TechTrends 2018, 62, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. Effects of Green HRM Practices on Employee Workplace Green Behavior: The Role of Psychological Green Climate and Employee Green Values. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H. The Influence of Corporate Environmental Ethics on Competitive Advantage: The Mediation Role of Green Innovation. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-H. The Determinants of Green Product Development Performance: Green Dynamic Capabilities, Green Transformational Leadership, and Green Creativity. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Fostering green service innovation perceptions through green entrepreneurial orientation: The roles of employee green creativity and customer involvement. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 2640–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zuo, W. Arousing employee pro-environmental behavior: A synergy effect of environmentally specific transformational leadership and green human resource management. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 62, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurksiene, L.; Pundziene, A. The relationship between dynamic capabilities and firm competitive advantage. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2016, 28, 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Wu, W.; Liu, C.; Ji, J.; Gao, X. Empathetic leadership and employees’ innovative behavior: Examining the roles of career adaptability and uncertainty avoidance. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1371936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GHRM | 4.20 | 0.66 | 1 | |||

| OGI | 4.26 | 0.63 | 0.86 ** | 1 | ||

| UP | 1.85 | 0.73 | −0.71 ** | 0.68 ** | 1 | |

| EGC | 4.27 | 0.56 | 0.80 ** | 0.77 ** | −0.68 ** | 1 |

| EGC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | ||||

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| (constant) | 0.464 | 0.228 | 0.220 | 0.179 | 0.251 | 0.192 |

| Gender | 0.049 | 0.04 | 0.044 | 0.031 | 0.056 | 0.033 |

| Age | −0.037 | 0.036 | −0.002 | 0.028 | −0.012 | 0.030 |

| Education | −0.001 | 0.038 | 0.015 | 0.03 | −0.011 | 0.032 |

| Years of working with leaders | 0.113 | 0.029 | 0.028 | 0.023 | 0.053 | 0.025 |

| Job level | 0.016 | 0.022 | −0.002 | 0.017 | −0.001 | 0.019 |

| Enterprise nature | −0.021 | 0.029 | −0.016 | 0.023 | 0.002 | 0.025 |

| Enterprise establishment year | 0.023 | 0.033 | 0.002 | 0.026 | −0.002 | 0.028 |

| Enterprise scale | 0.036 | 0.027 | 0.008 | 0.021 | 0.020 | 0.022 |

| Engaged in industry | −0.032 | 0.009 | −0.011 | 0.007 | −0.012 | 0.008 |

| Environmental awareness | 0.803 | 0.043 | 0.434 | 0.041 | 0.439 | 0.046 |

| GHRM | 0.485 *** | 0.03 | ||||

| OGI | 0.458 *** | 0.035 | ||||

| R2 | 0.546 | 0.725 | 0.682 | |||

| F | 47.951 *** | 95.204 *** | 77.255 *** | |||

| ∆R2 | 0.179 | 0.135 | ||||

| ∆F | 258.048 *** | 168.496 *** | ||||

| Variables | EGC | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mode (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | |

| (constant) | 0.464 | 1.790 | 1.584 |

| Gender | 0.049 | 0.048 | 0.036 |

| Age | −0.037 | −0.001 | −0.014 |

| Education | −0.001 | 0.008 | 0.017 |

| Years of working with leaders | 0.113 | 0.027 | 0.032 |

| Job level | 0.016 | −0.003 | 0.011 |

| Enterprise nature | −0.021 | −0.01 | −0.005 |

| Enterprise establishment year | 0.023 | −0.002 | −0.006 |

| Enterprise scale | 0.036 | 0.009 | 0.000 |

| Engaged in industry | −0.032 | −0.009 | −0.008 |

| Environmental awareness | 0.803 | 0.396 | 0.400 |

| GHRM, b1 | 0.386 *** | 0.348 *** | |

| GHRM b2 | 0.142 ** | 0.429 ** | |

| GHRM2, b3 | 0.111 ** | ||

| GHRM × OGI, b4 | −0.17 ** | ||

| OGI2, b5 | 0.180 *** | ||

| R2 | 0.546 | 0.731 | 0.748 |

| ∆R2 | 0.184 *** | 0.202 *** | |

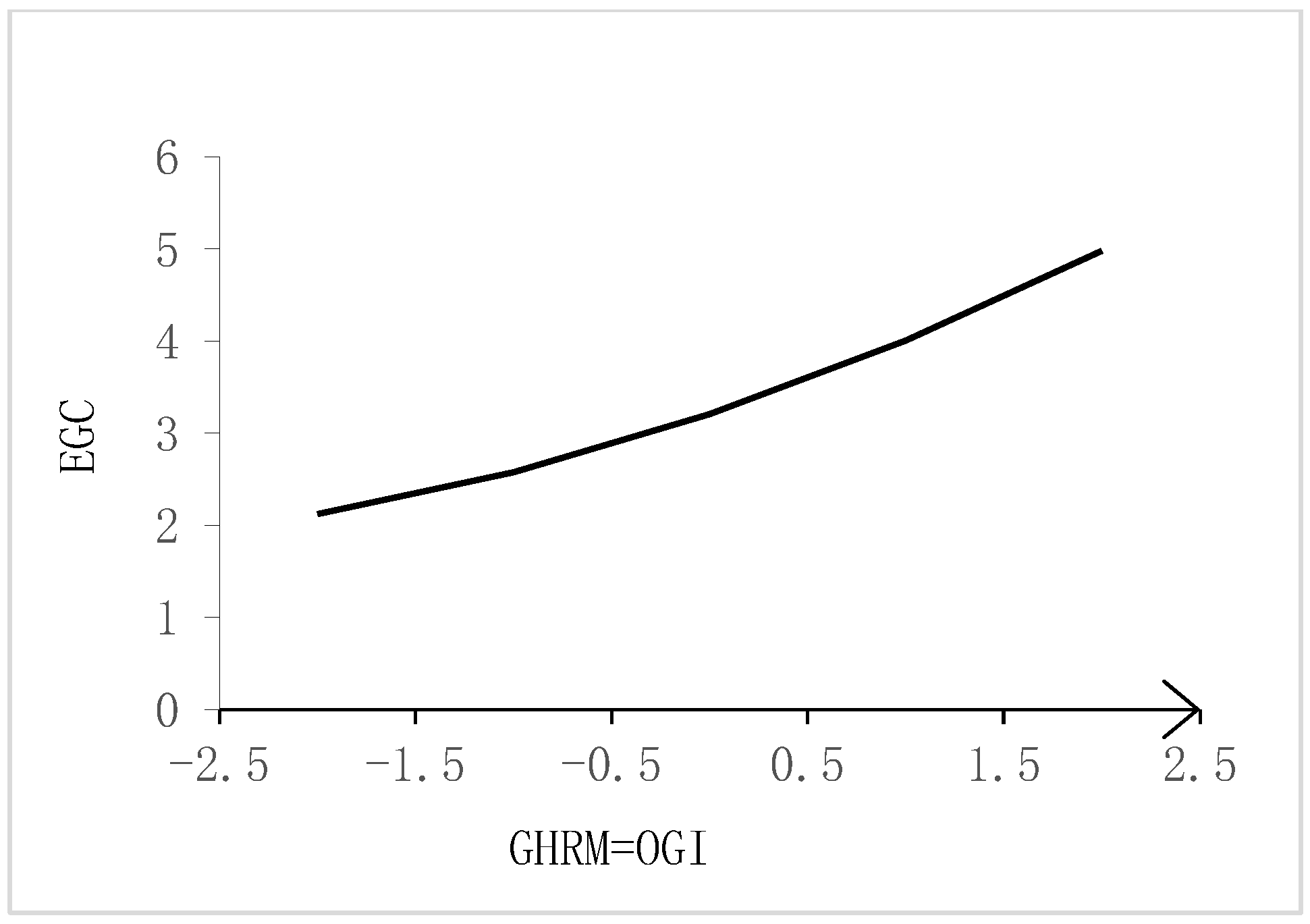

| Consistency line | |||

| slope (b1 + b2) | 0.777 *** | ||

| curvature (b3 + b4 + b5) | 0.121 ** | ||

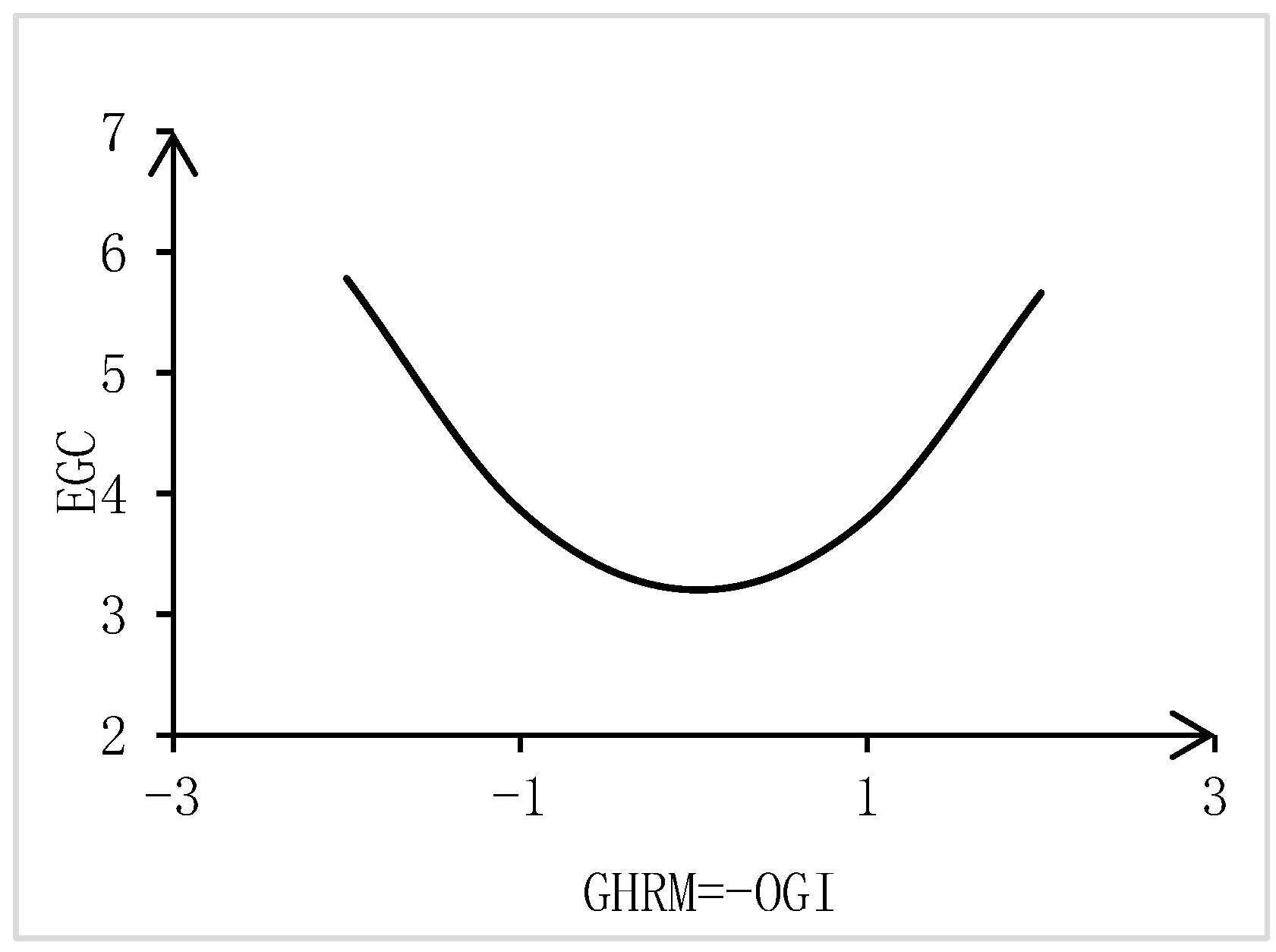

| Inconsistencies Line | |||

| slope (b1 − b2) | −0.081 | ||

| curvature (b3 − b4 + b5) | 0.461 *** | ||

| EGC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model (1) | Model (2) | |||

| B | SE | B | SE | |

| (constant) | 1.863 | 0.171 | 2.113 | 0.195 |

| Gender | 0.042 | 0.027 | 0.043 | 0.027 |

| Age | 0.003 | 0.025 | 0.003 | 0.025 |

| Education | 0.005 | 0.026 | 0.009 | 0.026 |

| Years of working with leaders | 0.011 | 0.020 | 0.006 | 0.020 |

| Job level | −0.008 | 0.015 | −0.007 | 0.015 |

| Enterprise nature | −0.001 | 0.020 | −0.002 | 0.020 |

| Enterprise establishment year | −0.004 | 0.023 | −0.005 | 0.023 |

| Enterprise scale | 0.006 | 0.018 | 0.008 | 0.018 |

| Engaged in industry | −0.005 | 0.007 | −0.002 | 0.007 |

| Environmental awareness | 0.253 | 0.040 | 0.245 | 0.039 |

| Block variable | 0.763 *** | 0.036 | 0.705 *** | 0.042 |

| CU | −0.068 | 0.026 | ||

| R2 | 0.786 | 0.789 | ||

| F | 132.259 *** | 123.533 *** | ||

| ∆R2 | 0.003 | |||

| ∆F | 8.726 ** | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jia, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M. The Green Dilemma: The Impact of Inconsistent Green Human Resource Management and Innovation on Employees’ Creative Performance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4831. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114831

Jia Q, Zhang Y, Liu M. The Green Dilemma: The Impact of Inconsistent Green Human Resource Management and Innovation on Employees’ Creative Performance. Sustainability. 2025; 17(11):4831. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114831

Chicago/Turabian StyleJia, Qiong, Yan Zhang, and Mengxin Liu. 2025. "The Green Dilemma: The Impact of Inconsistent Green Human Resource Management and Innovation on Employees’ Creative Performance" Sustainability 17, no. 11: 4831. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114831

APA StyleJia, Q., Zhang, Y., & Liu, M. (2025). The Green Dilemma: The Impact of Inconsistent Green Human Resource Management and Innovation on Employees’ Creative Performance. Sustainability, 17(11), 4831. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114831