Promoting Sustainable Island Tourism Through Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior: Integrating VIP, VAB, and TPB

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior

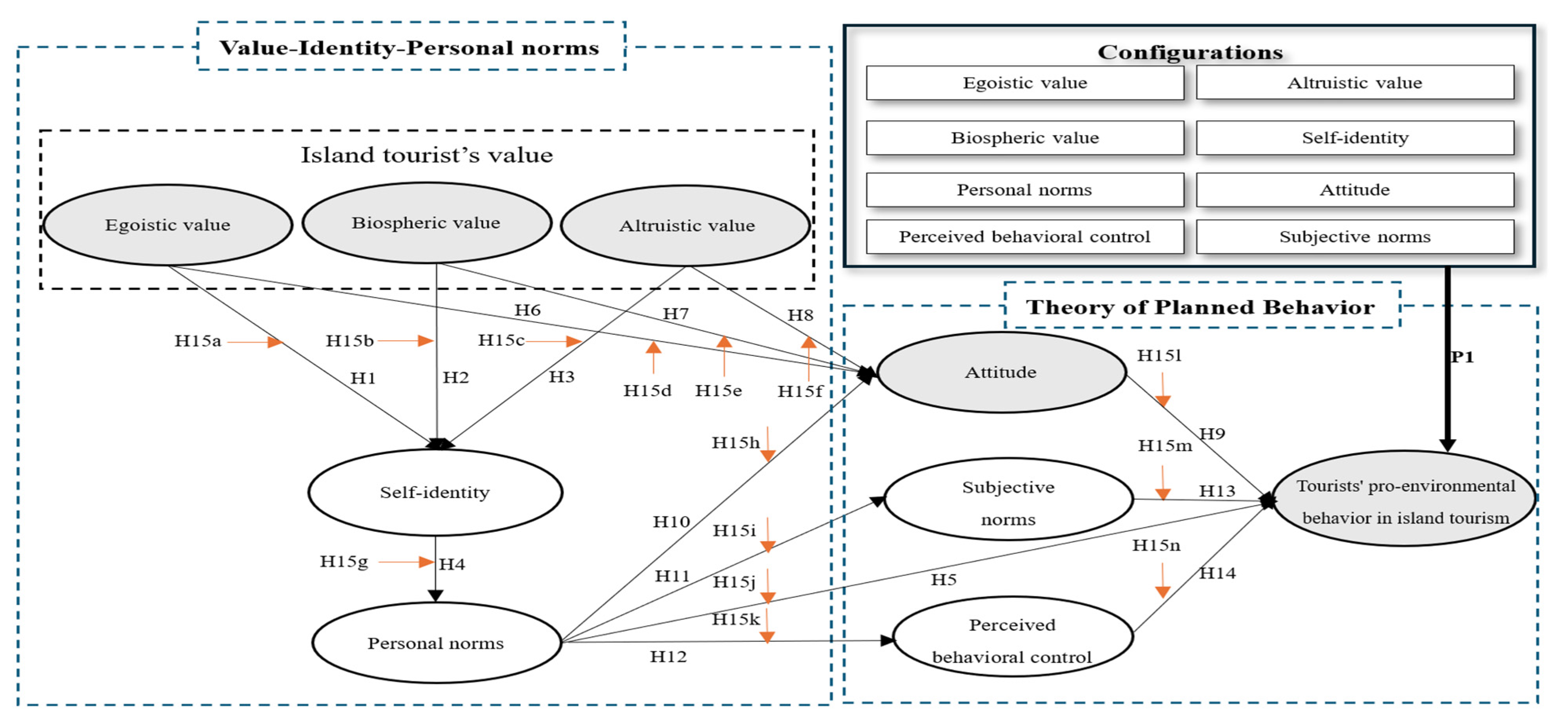

2.2. The Combination of the VIP, VAB, and TPB Models

2.3. The Value–Identity–Personal Norm Model

2.4. Value–Attitude–Behavior Model

2.5. Theory of Planned Behavior

2.6. Moderating Effect: Nationality

2.7. Configurations Leading to TERB

3. Case Study and Methodology

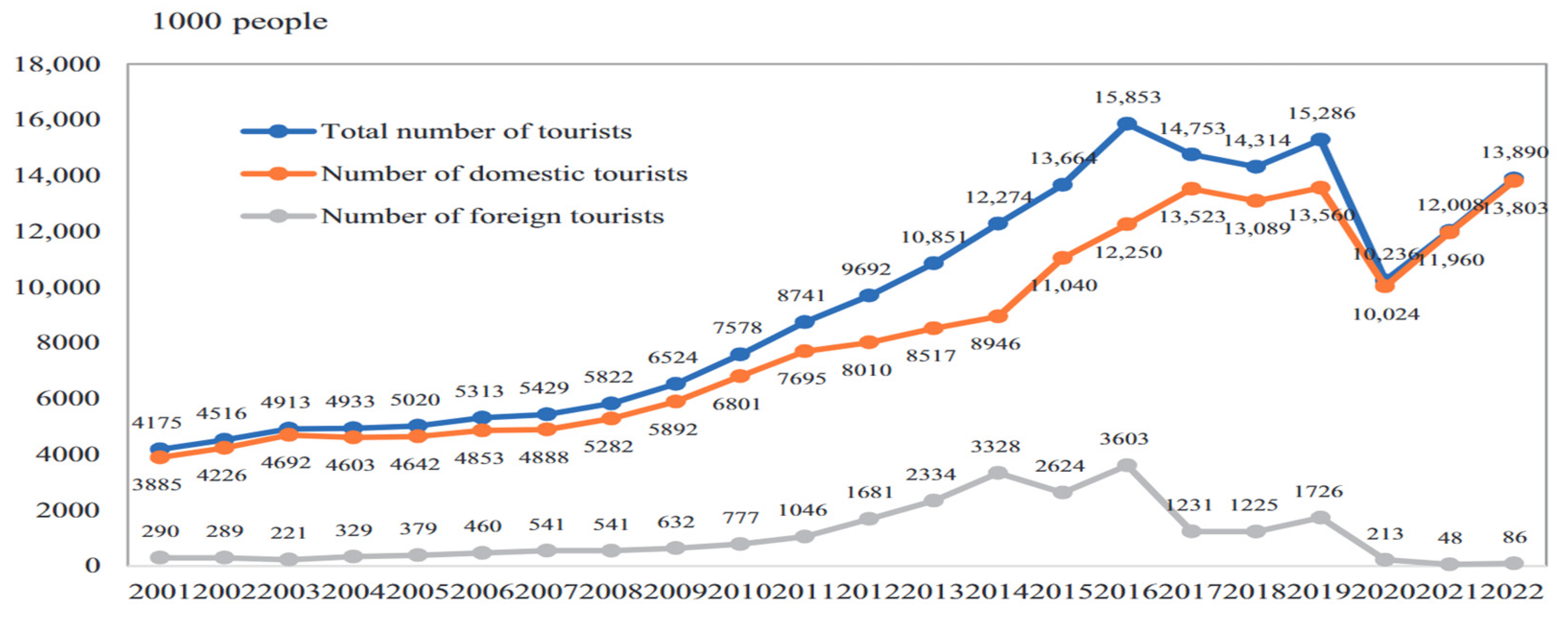

3.1. Research Case: Jeju Island

3.2. Questionnaire Design

3.3. Measures

3.4. Data Collection

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Sample Overview

4.2. Tests of Normality and Common Method Bias and Normality Test

4.3. Measurement Model Evaluation

4.4. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

4.5. Moderating Effect Analysis

4.6. Necessary Condition Analysis

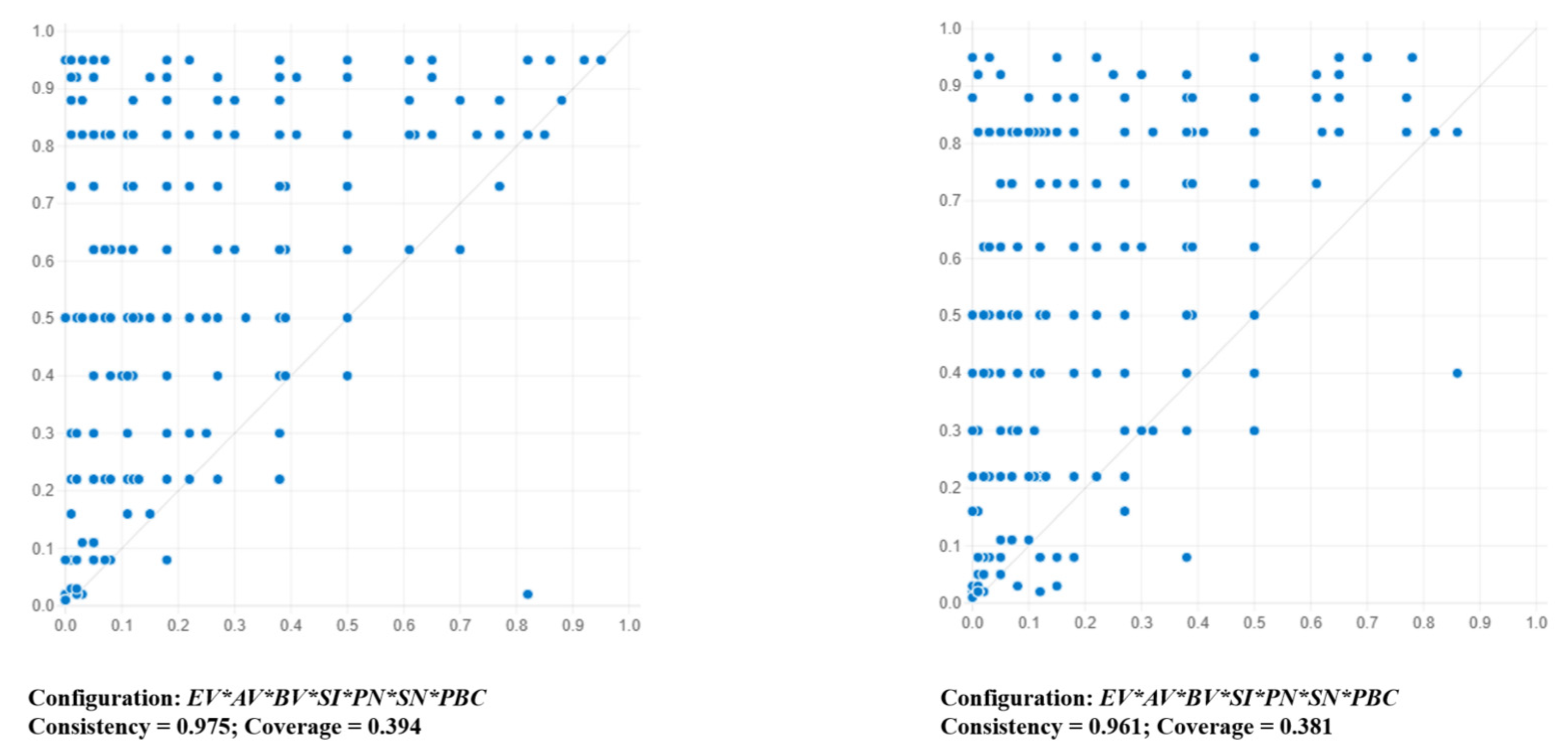

4.7. Sufficient Configurations

4.8. Tests of Predictive Validity and Robustness

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Managerial Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TERB | Tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior |

| VIP | Value–identity–personal norm |

| VAB | Value–attitude–behavior |

| TPB | Theory of planned behavior |

| SEM | Structural equation modeling |

| fsQCA | Fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis |

| UNWTO | United Nations World Tourism Organization |

| SIDSs | Small island developing states |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization |

| SI | Self-identity |

| PN | Personal norms |

| EV | Egoistic value |

| AV | Altruistic value |

| BV | Biospheric value |

| AT | Attitude |

| SN | Subjective norms |

| PBC | Perceived behavioral control |

| Λ | Factor loading |

| M | Mean |

| CR | Composite reliability |

| AVE | Average variance extracted |

| Skew | Skewness |

| Kurt | Kurtosis |

| X2/df | Chi-square/degrees of freedom |

| NFI | Normed fit index |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis index |

| CFI | Comparative fit index |

| RMSEA | Root mean square error of approximation |

| NCA | Necessary condition analysis |

| SCA | Sufficient condition analysis |

| PRI | Proportional reduction in inconsistency |

References

- Gao, J.; Song, L. A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Island Vacation Experience: Empirical Evidence from the Maldives. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 29, 804–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, F.; Adrianto, L.; Bengen, D.G.; Prasetyo, L.B. The Social-Ecological Status of Small Islands: An Evaluation of Island Tourism Destination Management in Indonesia. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripvivid. World Island Tourism Development Report. 2019. Available online: https://www.tripvivid.com/ (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- UNWTO. Tourism in Small Island Developing States (SIDS); World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, B.T.; Lee, T.J.; Li, X. Sustainable Development for Small Island Tourism: Developing Slow Tourism in the Caribbean. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2021, 38, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakfare, P.; Manosuthi, N.; Lee, J.S.; Promsivapallop, P.; Kang, H.; Han, H. Eliciting Small Island Tourists’ Ecological Protection, Water Conservation, and Waste Reduction Behaviours. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2024, 32, 100900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jin, L.; Pan, X.; Wang, Y. Pro-Environmental Behavior of Tourists in Ecotourism Scenic Spots: The Promoting Role of Tourist Experience Quality in Place Attachment. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Li, Y. Evaluation of Sustainable Tourism Development in Dachen Island, East China Sea: Stakeholders’ Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Lin, Y.; Cheng, X.; Ahn, Y.J.; Chi, X. An Investigation into the Formation of Tourists’ Pro-Environmental Behavior in Geotourism: Balancing Tourism and Ecosystem Preservation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Zhang, Q.; Khan, I.U.; Khan, S.U.; Mehmood, S. Tourists’ Pro-Environmental Behaviour in an Autonomous Vehicle’s Adoption: Aligning the Integration of Value-Belief-Norm Theory and the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Kang, H.; Tan, H.; Hwang, J. Environmental Locus of Control in Island Travelers and Pro-Environmental Behavior. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, H.J.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, C.K. A Moderator of Destination Social Responsibility for Tourists’ Pro-Environmental Behaviors in the VIP Model. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateş, H. Merging Theory of Planned Behavior and Value Identity Personal Norm Model to Explain Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 24, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, K.; Petersen, L.; Hörisch, J.; Battenfeld, D. Green Thinking but Thoughtless Buying? An Empirical Extension of the Value-Attitude-Behaviour Hierarchy in Sustainable Clothing. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 1155–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govaerts, F.; Olsen, S.O. Consumers’ Values, Attitudes and Behaviours Towards Consuming Seaweed Food Products: The Effects of Perceived Naturalness, Uniqueness, and Behavioural Control. Food Res. Int. 2023, 165, 112417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Pan, J. The Investigation of Green Purchasing Behavior in China: A Conceptual Model Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior and Self-Determination Theory. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 77, 103667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakfare, P.; Wattanacharoensil, W. Low-Carbon Tourism for Island Destinations: A Crucial Alternative for Sustainable Development. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, N.M.; Ahmad, S.Z.; Papastathopoulos, A. The Moderating Role of Nationality in Residents’ Perceptions of the Impacts of Tourism Development in the United Arab Emirates. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azali, M.; Kamal Basha, N.; Chang, Y.S.; Lim, X.J.; Cheah, J.H. Why Not Travel to Malaysia? Variations in Inbound Tourists’ Perceptions Toward Halal-Friendly Destination Attributes. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2023, 47, 177–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Xu, D.; Pan, Y. Configurational Paths to Arouse Tourists’ Positive Experiences in Smart Tourism Destinations: A fsQCA Approach. Sage Open 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y. From Inner Needs to External Actions: The Impact of Face Consciousness on Tourists’ Pro-Environmental Behavior. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2025, 30, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Wan, L.; Wang, H. Social Norms and Tourists’ Pro-Environmental Behaviors: Do Ethical Evaluation and Chinese Cultural Values Matter? J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 1413–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.; Pereira, O.; Simões, C. Determinants of Consumers’ Intention to Visit Green Hotels: Combining Psychological and Contextual Factors. J. Vacat. Mark. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alencastro, L.A.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, W. Preferences of Experiential Fishing Tourism in a Marine Protected Area: A Study in the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakfare, P.; Wattanacharoensil, W. Sustainable Consumption in Tourism: Perceptions of Low-Carbon Holidays in Island Destinations–A Cluster Analysis Approach. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 29, 641–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Yoon, Y.; Gan, M.; Hwang, J. Voluntary and Collective Payment Intentions for Sustainable Island Tourism: An Investigation Using an Extended Value-Belief-Norm Theory. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2025, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacout, O.M. Personal Values, Consumer Identities, and Attitudes Toward Electric Cars among Egyptian Consumers. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2023, 32, 1563–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Jang, S. Understanding Beach Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behaviors: An Extended Value-Attitude-Behavior Model. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2021, 38, 696–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, M.; Adil, M.; Paul, J. Eco-Friendly Hotel Stay and Environmental Attitude: A Value-Attitude-Behaviour Perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 100, 103094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Hsu, C.H. Urban Travelers’ Pro-Environmental Behaviors: Composition and Role of Pro-Environmental Contextual Force. Tour. Manag. 2022, 92, 104561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiar, K.; Pearce, J.; Dowling, R.; Goh, E. The Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour Model and National Parks Visitors’ Pro-Environmental Binning Behaviour: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2023, 42, 100602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, E.; Mulgrew, K.; Kannis-Dymand, L.; Schaffer, V.; Hoberg, R. Theory of Planned Behaviour: Predicting Tourists’ Pro-Environmental Intentions after a Humpback Whale Encounter. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah, M.; Forouzani, M. Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Predict Iranian Students’ Intention to Purchase Organic Food. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Wong, P.P.W. Purchase Intention for Green Cars among Chinese Millennials: Merging the Value–Attitude–Behavior Theory and Theory of Planned Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 786292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.J.; Hall, C.M.; Kim, D.K. Predicting Environmentally Friendly Eating Out Behavior by Value-Attitude-Behavior Theory: Does Being Vegetarian Reduce Food Waste? J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 797–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werff, E.; Steg, L. The Psychology of Participation and Interest in Smart Energy Systems: Comparing the Value-Belief-Norm Theory and the Value-Identity-Personal Norm Model. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 22, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floress, K.; Shwom, R.; Caggiano, H.; Slattery, J.; Cuite, C.; Schelly, C.; Lytle, W. Habitual Food, Energy, and Water Consumption Behaviors among Adults in the United States: Comparing Models of Values, Norms, and Identity. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 85, 102396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hwang, J.; Lee, M.J.; Kim, J. Word-of-Mouth, Buying, and Sacrifice Intentions for Eco-Cruises: Exploring the Function of Norm Activation and Value-Attitude-Behavior. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavuri, R.; Roubaud, D.; Grebinevych, O. Sustainable Consumption Behaviour: Mediating Role of Pro-Environment Self-Identity, Attitude, and Moderation Role of Environmental Protection Emotion. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 347, 119106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, P.M.; Kahle, L.R. A Structural Equation Test of the Value-Attitude-Behavior Hierarchy. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.H.; Moon, H.; Jung, S.E.; Severt, K. The Effect of Environmental Values and Attitudes on Consumer Willingness to Pay More for Organic Menus: A Value-Attitude-Behavior Approach. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 33, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Chen, W. Environmental Values, Face, and Ecotourism Intention in China: The Mediating Role of Ecotourism Attitude and the Moderating Role of Emotional Intelligence. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 61, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, W.W. Family Education? Unpacking Parental Factors for Tourism and Hospitality Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2021, 29, 100284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Ma, Y.; Li, Y. A Rational-Affective-Moral Factor Model for Determining Tourists’ Pro-Environmental Behaviour. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 2145–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuhin, M.K.W.; Miraz, M.H.; Habib, M.M.; Alam, M.M. Strengthening Consumers’ Halal Buying Behaviour: Role of Attitude, Religiosity and Personal Norm. J. Islam. Mark. 2022, 13, 671–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, I.; Sharpley, R. Influences of Nationalism on Tourist-Host Relationships. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 2051–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.C.; Jordan, E.; Santos, C. The Effect of Nationality on Visitor Satisfaction and Willingness to Recommend a Destination: A Joint Modeling Approach. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 39, 100850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Jeong, J.Y. The Effects of Health Beliefs upon Nature-Based Tourism During COVID-19: Cases from the United States and South Korea. J. Leis. Res. 2023, 54, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manosuthi, N.; Lee, J.S.; Han, H. Investigating Residents’ Support for Muslim Tourism: The Application of IGSCA-SEM and fsQCA. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2022, 39, 412–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, S.; He, B.; Huang, G. The Role of Motivation in the Subjective Well-Being of Older Adult Sojourners: An Investigation Using a Hybrid Technique of PLS-SEM and fsQCA. J. Vacat. Mark. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Cheng, X.; Zhou, H.; Zheng, X.; Cao, J.; Han, H. Investigation on Driving Mechanism of Heritage Tourism Consumption: A Multi-Method Analytical Approach. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2024, 41, 1141–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Han, S.; Park, J.H. What Drives Long-Stay Tourists to Revisit Destinations? A Case Study of Jeju Island. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 27, 856–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Choi, K.W.; Chang, M.; Lee, C.H. Overtourism in Jeju Island: The Influencing Factors and Mediating Role of Quality of Life. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W. Climate Change and Tourism Sustainability in Jeju Island Landscape. Sustainability 2022, 15, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr, F.; Gabriel, M.L.; Patel, V.K. AMOS Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modeling (CB-SEM): Guidelines on Its Application as a Marketing Research Tool. Remark Rev. Bras. Mark. 2014, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P.J.; West, S.G.; Finch, J.F. The Robustness of Test Statistics to Nonnormality and Specification Error in Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dul, J. Identifying Single Necessary Conditions with NCA and fsQCA. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1516–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Olya, H. The Combined Use of Symmetric and Asymmetric Approaches: Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modeling and Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 1571–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragin, C.C. Redesigning Social Inquiry: Fuzzy Sets and Beyond; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, A.M.; Farhangmehr, M.; Shoham, A. Hofstede’s Dimensions of Culture in International Marketing Studies. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Melech, G.; Lehmann, A.; Burgess, S.; Harris, M.; Owens, V. Extending the Cross-Cultural Validity of the Theory of Basic Human Values with a Different Method of Measurement. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2001, 32, 519–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, R.F.; Zhang, L. The Influence of Trekkers’ Personal and Subjective Norms on Their Pro-Environmental Behaviors. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2024, 48, 100836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radić, I.; Monaco, C.; Cerdan, C.; Peri, I. Establishing Communities of Value for Sustainable Localized Food Products: The Case of Mediterranean Olive Oil. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study/Contexts | Theory | Variables | Results | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al. [12]/ Wetland tourism | VIP | Biospheric value; environmental self-identity; personal norms | There is a significant progressive relationship between tourists’ biospheric value, environmental self-identity, and personal norms. | This model does not enable a thorough exploration of the interaction between egoistic and altruistic values, weakening its explanatory power regarding value-driven environmental decision-making. Additionally, its neglect of social norms limits the ability to capture group behavioral dynamics, hindering a comprehensive understanding of the synergy between individual rationality and collective constraint. |

| Yacout [27]/ Sustainable transportation | VIP | Altruistic value; egoistic value; biospheric value, pro-environmental identity; personal norms; attitudes | Biospheric value enhances environmental self-identity, while altruistic and egoistic values exhibit no significant effects. In turn, self-identity strengthens personal norms, which promote pro-environmental attitudes. | Despite its emphasis on environmental attitudes, this study fails to extend its analysis to consumers’ actual purchase intentions or behavioral outcomes, thereby falling short in explaining the gap between attitudes and behaviors. This limitation reduces the model’s predictive validity regarding real-world actions and constrains its practical applicability for policy recommendations and behavioral interventions. |

| Liu [28]/ Beach tourism | VAB | Biosphere value; attitude towards taking environmentally responsible behaviors; environmentally responsible behavioral intention | Biospheric value did not directly stimulate tourists’ positive attitudes toward pro-environmental behavior, indicating a limited influence at the attitude-formation stage; however, attitude plays a crucial role in shaping pro-environmental intentions. | An overemphasis on biosphere value in explaining attitude formation can obscure the roles played by individual personality traits and social axioms. Such a value-centric approach risks offering a limited perspective on attitude development, thereby weakening the model’s applicability and explanatory scope across different social settings. |

| Sadiq [29]/ Eco-friendly hotel stay | VAB | Altruistic value; egoistic value; environmental attitude; eco-friendly behavior | Tourists’ altruistic and egoistic values are positively associated with their environmental attitudes, which in turn positively influence their pro-environmental behaviors. | Prioritizing individual psychological factors tends to downplay the significant influence of social pressure and group dynamics on behavioral intentions. This individual-centric perspective may result in a fragmented understanding of what drives pro-environmental behavior, neglecting the impact of external forces like group norms embedded in social contexts. |

| Qin [30]/ Urban tourism | TPB | Attitude; subjective norms; perceived behavioral control; pro-environmental behavior | Attitude and perceived behavioral control significantly influence tourists’ pro-environmental behavior, whereas the association between subjective norms and tourists’ pro-environmental behavior is not significant. | Approaches emphasizing rational and self-interested psychological mechanisms tend to overlook the influence of personal moral norms as intrinsic motivators. This focus may hinder a full understanding of the moral foundations underlying tourists’ pro-environmental behavior, limiting the model’s ability to account for non-rational drivers such as a sense of responsibility and obligation. |

| Esfandiar [31]/ National Parks | TPB | Attitude towards bin use; social norms towards bin use; perceived behavioral control towards bin use; binning behavior | In addition to attitude, both social norms and perceived behavioral control have significant effects on national park visitors’ pro-environmental sorting behavior. | While cultural values were assessed, the absence of self-identity led to a failure to capture its potential influence on environmental attitudes. As an emotional connection to a cultural group, self-identity can play a crucial role in shaping tourists’ attitudes. Its omission may partly explain the weak attitude-related findings and limit a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms driving pro-environmental behavior. |

| Clark [32]/ Whale watching | TPB | Attitude; subjective norms; perceived behavioral control; reducing plastic consumption behaviors | Subjective norms have a significant influence on pro-environmental behavior, whereas attitude and perceived behavioral control exhibit no significant effects. | The explanation of tourists’ intrinsic motivations and value orientations related to pro-environmental behavior remains limited. Key psychological mechanisms such as environmental values, moral responsibility, and identity are insufficiently addressed, restricting a comprehensive understanding of the complexity behind tourists’ psychological and behavioral decision-making processes. |

| Category | Characteristics | N (575) | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 331 | 57.6 |

| Female | 244 | 42.4 | |

| Age | Younger than 20 years old | 23 | 4.0 |

| 20–29 years old | 210 | 36.5 | |

| 30–39 years old | 123 | 21.4 | |

| 40–49 years old | 102 | 17.7 | |

| 50 years old or more | 117 | 20.3 | |

| Education | High school diploma or less | 34 | 5.9 |

| Associate degree | 109 | 19.0 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 304 | 52.9 | |

| Master’s degree or higher | 128 | 22.3 | |

| Occupation | Student | 68 | 11.8 |

| White collar | 216 | 37.6 | |

| Official | 111 | 19.3 | |

| Self-employed | 77 | 13.4 | |

| Professional | 92 | 16.0 | |

| Others | 11 | 1.9 | |

| Nationality | Korean | 272 | 47.3 |

| Foreigner | 303 | 52.7 |

| Constructs and Items | λ | M | Skew | Kurt | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egoistic value (EV) | 0.564 | 0.795 | ||||

| EV1. Engaging in pro-environmental behavior makes me feel prouder about myself. | 0.762 | 4.821 | −0.352 | −0.155 | ||

| EV2. Engaging in pro-environmental behavior makes me have more respect for myself. | 0.755 | 4.812 | −0.351 | 0.450 | ||

| EV3. Engaging in pro-environmental behavior enhances my self-esteem. | 0.735 | 4.850 | −0.399 | 0.008 | ||

| Altruistic value (AV) | 0.528 | 0.770 | ||||

| AV1. Engaging in pro-environmental behavior contributes to the ecological protection of Jeju Island. | 0.726 | 4.788 | −0.446 | −0.278 | ||

| AV2. Engaging in pro-environmental behavior enhances the well-being of Jeju Island residents. | 0.694 | 4.866 | −0.462 | −0.374 | ||

| AV3. Engaging in pro-environmental behavior improves the environmental quality of Jeju Island. | 0.759 | 4.847 | −0.491 | −0.036 | ||

| Biospheric value (BV) | 0.609 | 0.824 | ||||

| BV1. We need to respect the Earth. | 0.789 | 5.023 | −0.629 | 0.071 | ||

| BV2. We need to coexist harmoniously with other species. | 0.752 | 4.958 | −0.584 | 0.212 | ||

| BV3. We need to prevent pollution and protect natural resources. | 0.800 | 5.028 | −0.697 | 0.365 | ||

| Self-identity (SI) | 0.765 | 0.929 | ||||

| SI1. Protecting the environment is an important part of my life. | 0.850 | 5.266 | −0.731 | 0.784 | ||

| SI2. I engage in pro-environmental behavior while participating in tourism. | 0.824 | 5.311 | −0.726 | 0.617 | ||

| SI3. I consider myself a pro-environmental-conscious person. | 0.880 | 5.374 | −0.648 | 0.465 | ||

| SI4. I consider myself a person who is willing to protect the environment. | 0.941 | 5.336 | −0.805 | 0.977 | ||

| Personal norms (PN) | 0.668 | 0.889 | ||||

| PEPN1. I feel morally responsible for reducing my impact on Jeju Island’s environment. | 0.860 | 5.104 | −0.785 | 0.497 | ||

| PEPN2. I feel a moral obligation to reduce my impact on Jeju Island’s environment. | 0.814 | 5.113 | −0.781 | 0.437 | ||

| PEPN3. I would feel guilty if I caused harm to Jeju Island’s environment. | 0.763 | 5.129 | −0.774 | 0.447 | ||

| PEPN4. Minimizing the impact on Jeju Island’s environment is the right thing to do. | 0.829 | 5.141 | −0.740 | 0.431 | ||

| Attitude (AT) | 0.634 | 0.838 | ||||

| AT1. For me, engaging in pro-environmental behavior in Jeju Island is good. | 0.820 | 4.873 | −0.658 | 0.304 | ||

| AT2. For me, engaging in pro-environmental behavior in Jeju Island is a wise choice. | 0.808 | 4.901 | −0.509 | 0.070 | ||

| AT3. For me, engaging in pro-environmental behavior in Jeju Island is enjoyable. | 0.759 | 4.892 | −0.506 | −0.030 | ||

| Subjective norms (SN) | 0.648 | 0.847 | ||||

| SN1. Most people who are important to me believe that I should engage in pro-environmental behavior. | 0.795 | 5.024 | −0.622 | 0.007 | ||

| SN2. Most people who are important to me hope that I will engage in pro-environmental behavior. | 0.824 | 4.998 | −0.679 | 0.146 | ||

| SN3. The people whose opinions I value are more likely to want me to engage in pro-environmental behavior. | 0.797 | 4.934 | −0.627 | 0.154 | ||

| Perceived behavioral control (PBC) | 0.558 | 0.791 | ||||

| PBC1. Whether I engage in pro-environmental behavior is entirely up to me. | 0.750 | 5.082 | −0.539 | −0.366 | ||

| PBC2. I believe that if I want to, I can engage in pro-environmental behavior. | 0.783 | 4.925 | −0.491 | −0.455 | ||

| PBC3. I have the resources, time, and opportunities to engage in pro-environmental behavior. | 0.707 | 5.035 | −0.632 | −0.263 | ||

| Tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior | 0.750 | 0.900 | ||||

| TERB1. I am willing to engage in pro-environmental behavior in Jeju Island. | 0.859 | 5.030 | −0.705 | 0.234 | ||

| TERB2. I would recommend other tourists to engage in pro-environmental behavior in Jeju Island. | 0.854 | 5.064 | −0.781 | 0.417 | ||

| TERB3. I would encourage other tourists to engage in pro-environmental behavior in Jeju Island. | 0.885 | 5.038 | −0.654 | 0.076 | ||

| Constructs | EV | AV | BV | SI | PN | AT | SN | PBC | TERB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EV | 0.751 | ||||||||

| AV | 0.669 | 0.727 | |||||||

| BV | 0.677 | 0.651 | 0.781 | ||||||

| SI | 0.471 | 0.446 | 0.477 | 0.875 | |||||

| PN | 0.430 | 0.427 | 0.577 | 0.485 | 0.818 | ||||

| AT | 0.622 | 0.570 | 0.618 | 0.393 | 0.518 | 0.796 | |||

| SN | 0.421 | 0.276 | 0.351 | 0.344 | 0.404 | 0.429 | 0.805 | ||

| PBC | 0.374 | 0.299 | 0.402 | 0.398 | 0.433 | 0.263 | 0.385 | 0.747 | |

| TERB | 0.411 | 0.358 | 0.509 | 0.361 | 0.546 | 0.455 | 0.510 | 0.415 | 0.866 |

| Hypotheses | Paths | Coefficient | t-Value | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | EV→SI | 0.226 ** | 2.786 | Supported |

| H2 | BV→SI | 0.260 *** | 3.544 | Supported |

| H3 | AV→SI | 0.171 * | 2.105 | Supported |

| H4 | SI→PN | 0.55 *** | 11.819 | Supported |

| H5 | PN→TERB | 0.282 *** | 5.258 | Supported |

| H6 | EV→AT | 0.304 *** | 3.933 | Supported |

| H7 | BV→AT | 0.209 ** | 3.038 | Supported |

| H8 | AV→AT | 0.171 * | 2.241 | Supported |

| H9 | AT→TERB | 0.206 *** | 4.116 | Supported |

| H10 | PN→AT | 0.208 *** | 5.736 | Supported |

| H11 | PN→SN | 0.434 *** | 9.037 | Supported |

| H12 | PN→PBC | 0.413 *** | 8.973 | Supported |

| H13 | SN→TERB | 0.270 *** | 5.982 | Supported |

| H14 | PBC→TERB | 0.164 ** | 3.178 | Supported |

| Control variable | Gender→TERB | −0.154 | −1.835 | Not Supported |

| Age→TERB | 0.006 | 0.165 | Not Supported | |

| Education→TERB | 0.101 * | 1.957 | Supported |

| Hypothesis | Paths | Coefficient | LLCI (95%) | ULCI (95%) | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H15a | EV × NA→SI | −0.15 | −0.310 | 0.010 | Not Supported |

| H15b | BV × NA→SI | 0.12 | −0.272 | 0.030 | Not Supported |

| H15c | AV × NA→SI | −0.01 | −0.169 | 0.143 | Not Supported |

| H15d | EV × NA→AT | −0.09 | −0.249 | 0.067 | Not Supported |

| H15e | BV × NA→AT | −0.16 * | −0.305 | −0.007 | Supported |

| H15f | AV × NA→AT | −0.20 * | −0.356 | −0.044 | Supported |

| H15g | SI × NA→PN | −0.20 ** | −0.350 | −0.051 | Supported |

| H15h | PN × NA→AT | −0.19 * | −0.338 | −0.044 | Supported |

| H15i | PN × NA→SN | 0.03 | −0.145 | 0.200 | Not Supported |

| H15j | PN × NA→TERB | 0.08 | −0.084 | 0.370 | Not Supported |

| H15k | PN × NA→PBC | 0.08 | −0.087 | 0.238 | Not Supported |

| H15l | AT × NA→TERB | −0.18 * | −0.342 | −0.017 | Supported |

| H15m | SN × NA→TERB | 0.02 | −0.129 | 0.160 | Not Supported |

| H15n | PBC × NA→TERB | −0.04 | −0.195 | 0.117 | Not Supported |

| Outcome (TERB) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Conditions | Consistency | Coverage |

| EV | 0.710 | 0.814 |

| ~EV | 0.621 | 0.648 |

| AV | 0.694 | 0.788 |

| ~AV | 0.609 | 0.641 |

| BV | 0.779 | 0.801 |

| ~BV | 0.541 | 0.630 |

| SI | 0.757 | 0.775 |

| ~SI | 0.549 | 0.643 |

| PN | 0.753 | 0.829 |

| ~PN | 0.568 | 0.615 |

| AT | 0.766 | 0.815 |

| ~AT | 0.570 | 0.640 |

| SN | 0.790 | 0.829 |

| ~SN | 0.552 | 0.629 |

| PBC | 0.759 | 0.806 |

| ~PBC | 0.564 | 0.635 |

| Configurations | Raw Coverage | Unique Coverage | Consistency |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1: EV × BV × PN × AT × SN × PBC | 0.432 | 0.008 | 0.966 |

| C2: BV × SI × PN × AT × SN × PBC | 0.444 | 0.012 | 0.963 |

| C3: EV × AV × BV × SI × PN × SN × PBC | 0.387 | 0.017 | 0.969 |

| C4: EV × AV × SI × PN × AT × SN × PBC | 0.382 | 0.012 | 0.969 |

| C5: AV × BV × PN × AT × SN × PBC | 0.419 | 0.003 | 0.967 |

| C6: EV × AV × BV × ~SI × PN × AT × SN | 0.283 | 0.025 | 0.982 |

| Solution coverage: 0.529 | |||

| Solution consistency: 0.954 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, Y.; Yoon, J.-H.; Xiao, G. Promoting Sustainable Island Tourism Through Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior: Integrating VIP, VAB, and TPB. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4792. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114792

Lin Y, Yoon J-H, Xiao G. Promoting Sustainable Island Tourism Through Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior: Integrating VIP, VAB, and TPB. Sustainability. 2025; 17(11):4792. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114792

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Yuhao, Ji-Hwan Yoon, and Guangyu Xiao. 2025. "Promoting Sustainable Island Tourism Through Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior: Integrating VIP, VAB, and TPB" Sustainability 17, no. 11: 4792. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114792

APA StyleLin, Y., Yoon, J.-H., & Xiao, G. (2025). Promoting Sustainable Island Tourism Through Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior: Integrating VIP, VAB, and TPB. Sustainability, 17(11), 4792. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114792