Abstract

The purpose of this article is to extend agency theory (AT) by applying it to social enterprises (SEs), which exhibit a dual focus on both corporate social responsibility (CSR) and profit-driven operations. This duality, often referred to as the double-bottom-line attribute, complicates the agency relationship within SEs and has led to conceptual unclear in previous studies. This study also explains why traditional AT and reciprocal theory are not applicable to the analysis of complex agency relationships in SEs. In response, this article builds upon traditional AT to propose a developmental framework that redefines the roles of principal and agent in SE contexts. This research proposes a new theory, Sustainability Agency Theory (SAT), which aims to more clearly define the dynamic agency relationships within SEs. The article further distinguishes SAT from other AT-based extensions, such as the reciprocal theory. By offering a theoretical extension to SEs, this study contributes a novel perspective to the literature on agency relationships in hybrid organizations. Furthermore, this article expands SAT through seven distinct dimensions, laying a strong foundation for future theoretical developments related to SAT.

1. Introduction

Over recent decades, there has been a growing interest in organizations that balance social and financial goals within their business models [1,2]. This dual approach offers significant benefits, as it enables for-profit companies to address social issues while simultaneously expanding their operations [3]. However, the inherent tensions between social and financial objectives often impede the growth and competitiveness of one or both domains [1]. When financial objectives take precedence, organizations risk experiencing “mission drift”, compromising their social goals. If financial growth requires strategies that diverge from a company’s social mission, overall progress can be adversely affected [4,5,6].

Social enterprises (SEs) are increasingly recognized as a viable solution to this tension, as they effectively balance social and financial demands [7,8]. Their capacity to maintain alignment with social missions while achieving financial sustainability has attracted growing scholarly and practical attention [8,9,10,11]. According to Wilburn and Wilburn [12], SEs operate with a dual bottom line, aiming to achieve both financial sustainability and social objectives. This operational model reflects a synergistic integration of financial and social returns, as SEs typically reinvest their earnings into their social missions [13]. By doing so, SEs can ensure that financial success directly supports the advancement of their social goals.

The benefits or profits generated by SEs are typically centered on the social value enhancement or addressing societal challenges [14]. Unlike traditional businesses, these benefits or profits are generally reinvested into the enterprise to further its social mission rather than being distributed as dividends to stakeholders or shareholders [13,15]. The aim of SEs is to address various social issues such as the reduction of environmental pollution, poverty reduction, and so on [16]. This characteristic distinctly differentiates SEs from other types of enterprises [17]. Recognizing the socio-economic value that SEs contribute by addressing community challenges, governments have developed and adapted legal frameworks and institutional support mechanisms to facilitate this business model. These measures have fostered synergies between governments and SEs, contributing to their growing prevalence and popularity [18,19].

Weaver and Blakey [20] posit that SEs represent a more sustainable form of social intervention compared to charitable organizations and embody a more socially conscious business model than conventional for-profit companies. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) plays an important role in SEs, because of the role of CSR in the process of social value development for corporations and non-profits [21]. By aligning their strategies with socially responsible principles, SEs can strengthen their social capital and enhance their competitive advantage [10,22]. Agency Theory (AT) is frequently applied in CSR research [23,24], and socially responsible practices often serve as a core strategic component within SEs [25]. AT focuses on the relationship between principals and agents, wherein the principal delegates tasks to the agent, who is then responsible for executing them [26,27]. This theory highlights the potential for agency costs and conflicts, particularly in cases where managers may exploit company resources for personal gain through corporate philanthropy, potentially leading to losses for shareholders [15,28,29]. However, as SEs are expected to maintain a double bottom line, managerial tensions arise whenever attempts are made to maximize financial performance and social value, creating conflict over financial and social objectives [13,30]. Because agency theory is a powerful tool for describing the conflictual relationships that exist within organizations, the researcher aims to use it to further analyze the internal dynamic conflicts in SEs.

Traditional AT shows that agents are predominantly motivated by financial returns, often at the expense of social responsibilities [24,31]. In the context of SEs, however, the principal–agent relationship is inherently dynamic, giving rise to complexities that traditional AT can hardly explain.

To address this theoretical gap, this study develops a novel theoretical framework tailored to the context of SEs, building on the foundational concepts of traditional AT. By refining and extending the roles traditionally assigned to principals and agents within the company, this new theory provides a clearer explanation of the inherent tension between social objectives and profit-making objectives. The aim of this study is to deepen the understanding of dynamic conflicts within SEs, particularly those arising from the interaction between social and financial objectives. To achieve this, this article develops a novel theoretical framework. In doing so, the new theory extends the application of AT into the field of SEs’ governance and contributes to a deeper theoretical exploration of hybrid organizational dynamics.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Enterprises (SEs)

2.1.1. Definition and Characteristics of SEs

According to Bridgstock et al. [32], SEs are generally characterized as small, focused on serving local communities, and often dealing with complex social issues. SEs simultaneously pursue social and commercial objectives, functioning as institutionally hybrid organizations that integrate both social and corporate logic [2]. Their primary goal is not only to generate profit but also to address social problems by maximizing community benefits, promoting eco-friendly products, and minimizing the exploitation of natural resources [22].

Furthermore, SEs are frequently characterized by their double bottom line, which signifies their dual focus on CSR activities and profit-driven business operations [33]. This distinctive approach challenges conventional organizational classifications, positioning SEs outside the traditional categories of private, public, or not-for-profit entities [13]. Four key dimensions are particularly relevant to SEs: social innovation, social mission, social networking, and financial returns [34]. Social innovation refers to any advancement in products or technologies that addresses societal needs [35], offering innovative and effective solutions to social challenges while creating social value [36]. SEs can help governments or business sectors to solve overlooked social problems by developing a synergistic combination of products, capabilities, processes, and technologies for sustainable business development [34]. The social mission is a defining feature of SEs, with the creation of social value as their core objective [37,38]. Moreover, social networking acts as a critical enabler for SE sustainability, providing access to vital resources and informational opportunities [34,39]. In terms of financial returns, SEs that seek to maximize both social impact and financial viability actively pursue opportunities to generate profits by addressing unmet societal needs [40].

SEs aim to generate social value by fostering collaboration among individuals and civil society groups [41]. The primary objective of social innovation is to develop innovative solutions that enhance economic activities across various fields of community life and the environment [42]. SEs not only address current social issues but also foster social innovations which encompass novel attitudes, thereby achieving more effective solutions to these problems than previously possible [43].

2.1.2. CSR Plays an Important Role for SEs

SEs are organizations that place a high value on CSR and implement it as a survival strategy, making a positive contribution to society by leveraging their social influence [44]. SEs also use their social influence to fulfil their social responsibility of providing sustainable growth [10]. Both CSR and social entrepreneurship extend beyond the mere provision of financial value, placing significant emphasis on social responsibility as a core element of their missions [25].

Apparently, SEs and CSR initiatives share a common goal of fostering a “better” society by encouraging businesses to prioritize stakeholders’ concerns and contribute meaningfully to addressing emerging social and environmental challenges [45]. In response to societal expectations, socially responsible practices within SEs contribute to value creation that enhances quality of life, highlighting their central role in SEs [46].

Furthermore, SEs need to take more time and effort to establish their presence in the marketplace and secure funding to support their CSR actions [32]. Hence, SEs frequently rely on external sources of funding such as grants, donations, and philanthropic contributions to sustain their operations and advance their social objectives [47]. To secure such funding, SEs must develop and maintain a strong reputation, as their credibility plays a crucial role in gaining the trust and confidence of key stakeholders, including donors, investors, and community partners [48]. A solid reputation not only helps SEs attract funding but also fosters the acquisition of social capital, which strengthens their ability to fulfil their social missions [47]. Moreover, this reputation, in turn, can enhance the motivation of frontline employees, leading to improved customer interactions and service outcomes [49].

2.2. Agency Theory (AT)

Agency theory, which can be traced back to Ross’s research in 1973, focuses on the agency problem and its potential solutions [50]. Meckling and Jensen [27] further developed the concept by defining the agency relationship as a contract under which one or more persons (the principal) engage another person (the agent) to perform services on their behalf, delegating some decision-making authority to the agent. On the one hand, the principal is typically the shareholder or the owner who invests capital with the aim of maximizing economic returns, in the corporate context. Conversely, the agent is the individual or group responsible for managing the company and may pursue personal utility or private gains [51]. The separation of ownership and control in large corporations creates inevitable conflicts between these two parties [23]. Agency conflict arises when the interests of the agent and the principal diverge.

Some researchers argue that corporate social responsibility (CSR) often reflects managerial agency problems within firms and can therefore be interpreted through the lens of AT [52,53]. According to AT, the involvement of businesses in CSR activities is driven by the self-interested actions of managers, which result from agency problems and reduce the company’s maximum profit value [54,55]. Managers engage in CSR activities instead of focusing solely on maximizing shareholder wealth because such initiatives can provide them with private benefits [56,57]. Bénabou and Tirole [53] found that corporations often donate to non-profit organizations or charities favored by their upper management. Similarly, Cespa and Cestone [58] observed that business leaders often gain popularity through such charitable efforts, leading to overinvestment in social programs for reputational advantage [59]. In addition, a number of studies have shown that firms facing strong internal or external accountability mechanisms often demonstrate weak performance in CSR. This underperformance reflects agency-related challenges within the organization [60,61]. When corporate spending on social programs exceeds optimal levels, stakeholders may question whether resources are being misallocated. This, in turn, can diminish trust, constrain stakeholder support, and increase both operational and agency costs [34,57]. Agency costs need to take into account the residual losses resulting from managerial behavior [26]. Engaging in CSR activities can impose financial burdens on companies, negatively impacting the allocation of limited resources while increasing management access to these resources [34,62]. Therefore, these factors cause principal–agent problems and position CSR as a tool that can serve managerial self-interest [63].

2.2.1. The Tension Within SEs

However, unlike traditional business models, CSR is one of the main objectives of SEs. SEs operate under a hybrid model, navigating a complex web of conflicting institutional demands that arise from their dual mission of achieving financial sustainability while creating social value [2,13]. In contrast to traditional businesses, which primarily focus on profit maximization, SEs are tasked with balancing the competing priorities of social impact and economic viability [13]. This balancing act often results in managerial tensions, as managers are required to allocate resources, make strategic decisions, and address the diverse expectations of stakeholders, including investors, employees, and beneficiaries [13]. The pursuit of profit and social value does not always align, leading to frequent tensions as SEs attempt to navigate these dual objectives [64]. SEs may seek to minimize costs and increase revenue through a mix of charitable donations, income from labor, and for-profit activities that support their social mission [65,66,67]. This approach often leans towards a utilitarian identity, where financial objectives are prioritized [68]. The utilitarian identity is presented as market-oriented and seeks to maximize benefits and minimize costs [68,69]. Conversely, their social mission, which emphasizes public welfare and aims to address social issues such as poverty alleviation and elderly care, and so on, is aligned more with a normative identity [68]. The normative identity is presented as socially oriented and focuses on social reputation [68,69]. The coexistence of these differing identities and priorities creates tensions within SEs as shown in prior studies [68,70].

While some literature suggests that social entrepreneurs skillfully balance social and financial goals through ingenuity [71,72,73], this perspective often overlooks the underlying tensions involved [74]. But empirical evidence from several studies confirms that these tensions persist, highlighting the paradox of pursuing a social mission through business means, which inherently involves competing demands related to social and financial objectives [14,75,76].

Based on Doherty et al. [13], founders of SEs are social entrepreneurs focused on pursuing social value creation within the corporate structure. Social entrepreneurs establish SEs with the primary goal of addressing social problems [77]. However, they are often characterized by a mindset that prioritizes individual social value creation over collective team efforts [78]. Investors are increasingly drawn to the dual promise of social impact and business value offered by SEs, which are seen as effective tools for addressing societal challenges while providing opportunities for financial returns [79]. Social entrepreneurs and investors have the aim of bringing a return on their investment in addition to the desire to bring a positive effect on society to enhance their image [64]. This dual mission places significant responsibilities on SE managers [14], who must navigate the complexities of pursuing both economic and social objectives [80]. Achieving this dual mission requires managers to possess a deep understanding of both business operations and the nuances of the social sector, and effectively balance the needs of employees while integrating knowledge from these diverse areas [81]. SE managers face challenges in managing the identity of hybrid organizations, responding to market pressures from customers and competitors, and integrating the typical mix of employees and volunteers [13]. Thus, internal conflicts in SEs arise mainly from the paradox of pursuing a social mission through commercial means. Internal conflicts within SEs can be effectively explored using agency theory. AT provides a framework for understanding how these conflicts manifest within SEs.

2.2.2. The Limitations of AT

AT pays attention to business relationships within a principal–agent framework, wherein one party, such as the principal, delegates decision-making authority to another party, such as the agent, who subsequently undertakes delegated tasks on their behalf [26]. Traditional AT focuses on a dyadic relationship between a principal and an agent, effectively capturing scenarios where a single stakeholder (the principal) delegates tasks to a single agent. However, this theoretical framework exhibits limitations when applied to examine multiple agents and principals involved. SEs typically strive to balance social impact with financial objectives, creating a double bottom line [82] that illustrates its complexity. This blend of mission-driven and market-oriented imperatives introduces a diverse array of interests and motivations among founders, investors, beneficiaries, and the broader community [83,84]. Consequently, agency relationships within SEs are inherently more intricate and are not sufficiently addressed by traditional principal–agent frameworks.

Nonetheless, agency models have continued to evolve to analyze multiple relationships, with reciprocal agency being a typical example. Building on Jeon’s [85] study, reciprocal agency posits a dynamic framework where the roles of agent and principal can interchange among multiple individuals engaged in various relationships, thereby challenging the static dyad of traditional models. A typical case involves the chairperson of a department or committee, who initially acts as an agent on behalf of other members, subsequently transitioning into a principal role upon the conclusion of his or her term [85]. This conceptualization of reciprocal agency underscores the heightened importance of incentive structures within such relationships, which aligns with Ross’s foundational argument [50]. According to Englmaier and Leider [86], reciprocal dynamics within principal–agent relationships can generate mutually beneficial outcomes when principals extend non-contractual incentives to agents. For instance, when a firm provides a generous benefit, such as additional compensation, to an agent, the agent is inclined to reciprocate by expending greater effort on behalf of the organization. This reciprocal dynamic enables firms to capitalize on agents’ reciprocal attitudes by aligning agents’ preferences with those of the firm, thereby fostering enhanced intrinsic motivation.

While reciprocal agency theory extends traditional agency frameworks by incorporating dynamic role interchangeability, its application to SEs remains comparatively limited. Firstly, a limitation is that the reciprocal dynamics described are often stage-specific, whereby changes in roles and identities occur only at the conclusion of one phase and the commencement of another. In contrast, roles in SEs do not follow specific stages, as they are dynamic and continuously evolving. For instance, social entrepreneurs may act as agents when procuring funding and grants from corporations or other organizations, and they may simultaneously function as principals when distributing resources to beneficiaries in need [83]. Consequently, the definitions of ‘agent’ and ‘principal’ within SEs differ from those in commercial firms. In the next section, this study therefore redefines principal–agent roles within the context of SEs.

Moreover, because SEs are inherently driven by a desire to contribute to society, both agents and principals ostensibly share the aim of generating social value. Nevertheless, in practice, they often seek to balance dual objectives (social impact and financial sustainability). It causes conflicting interests, thereby resulting in agency problems. These twin imperatives necessitate complex governance mechanisms, which, in turn, engender equally complex agency relationships [51]. This complexity aligns with Mitnick’s [87] institutional perspective, which posits that agency relationships are mediated by the normative and cognitive frameworks of their organizational ecosystems. This highlights the need for a new theoretical model to better analyze SEs.

3. Theory Building Approach

This study adopts a conceptual research methodology, grounded in a comprehensive literature review, to examine the limitations of traditional AT when applied to SEs. Through critical analysis of existing literature, the study develops a new theoretical framework called Sustainability Agency Theory (SAT). This framework aims to more accurately capture the complex and dynamic agency relationships within SEs.

The development of the SAT involved a three-step conceptual process. The first step involved exploring the distinct characteristics of SEs that create agency tensions, particularly their pursuit of both financial and social objectives. In contrast to traditional business models, SEs have a “double bottom line”, resulting in a more complex principal–agent relationship within them. Such conflicts occur when SEs try to balance the dual objectives of maximizing profit and achieving social performance [13,88]. For example, while principals prioritize CSR activities to enhance social value and fulfil the organization’s mission, agents may prefer focusing on securing profit to ensure the sustainable development of SEs, stable work performed by employees, stable employment for staff, and improvements in the services or goods provided over CSR activities.

The second step is reviewing relevant theoretical literature and identifying its limitations. In particular, this study examined the shortcomings of how traditional AT is applied within SEs. Agency conflict in SEs primarily arises from their inherently hybrid nature, which requires balancing multiple stakeholders’ demands that may sometimes conflict. For instance, when the principal’s primary focus is on the social mission, such as social entrepreneurs’ commitment to societal goals [14,89], agents may adopt a more commercially oriented approach to prevent excessive social expenditure that could lead to financial instability [14]. This tension is exemplified by Aspire, an organization in the UK that prioritized its social mission but ultimately faced financial bankruptcy [90]. The inherently commercial and social orientation of SEs further complicates this dynamic. Therefore, the agent in SEs must navigate two competing priorities: fulfilling the social mission set by the principal while simultaneously ensuring financial viability. This duality makes the principal–agent relationship in SEs uniquely complex and dynamic.

In the last step, the researchers synthesized the findings into a new conceptual framework. Drawing on the literature review concerning the nature of SEs and the identification of inherent tensions within SEs, this study developed the SAT model. The framework is structured around seven analytical dimensions, each reflecting a potential source of agency conflict in SEs.

A review of the existing literature illustrates that traditional agency theory, and its related theoretical frameworks are difficult to explain the dynamic and conflictual nature of principal and agent relationships within SEs. According to Mswaka and Aluko [91], defining the principal and the agent in SEs presents significant challenges. Unlike traditional AT, the aim of SEs is to improve social well-being and address social issues, and SEs need to balance profit-making objectives and social objectives [33,92]. In response to these complexities, the present study is guided by the following research questions, which aim to inform the adaptation and theoretical development of agency theory in the SE context:

- What are the key dimensions that cause dynamic agency relationships in social enterprises?

- How does SAT respond to the conflictual relationship between agents and principals in SEs?

4. Defining the Novel Theoretical Model—Sustainability Agency Theory (SAT)

To fully understand the internal conflicts within SEs, the researcher must redefine the concepts of principal and agent in this context.

SE members who instinctively want to achieve long-term social value are named as principals. On the other hand, SE members who are required to take actions to balance short-term profit-making objectives and social objectives are named as agents. Such members include all individuals involved in both the development and the execution of the SE’s strategic plans, encompassing key stakeholders (e.g., founders of SEs) and strategic implementers (e.g., employees). Since both CSR and profitability are essential to the sustainability of SEs, conflicts inevitably arise when one objective is prioritized over the other. For example, the founder of the SEs is the principal when he wants the company to realize long-term social value. However, SEs are not charitable organizations, and the founder of an SE is an agent when they take action to balance short-term profitability and social objectives. Hence, membership in SEs is a dynamic relationship because the priority tendency of agents and principals towards CSR and profit-making is constantly changing due to the influence of the external environment.

The conflict between principals and agents will increase when actions taken by agents are more focused on profit-making objectives. These profit-making actions are contrary to the priorities of principals who prioritize social objectives. It is important to note that prioritizing one objective does not mean that the other objective is abandoned or ignored; it is just a difference in priority. The researcher redefines the agency theory called Sustainability Agency Theory (SAT), which is suitable to study conflict between principals and agents in SEs. Although the agent is primarily profit-making, profit generation is a means to achieve or maintain social objectives. In order to better distinguish the traditional theory of agency, the researcher has designed Table 1 to explain and clarify these distinctions.

Table 1.

New definition of Agency Theory.

As the table describes that SAT is different from traditional AT. According to Panda and Leepsa [51], traditional AT is used to discuss the problems arising from conflicts of interest between principals and agents in firms due to the differing interests of owners and managers. This theory has been widely used in traditional business models. However, based on the research results of Mswaka and Aluko [91] and Low and Chinnock [93], the difficulty in applying traditional AT to SEs lies in the dynamic nature of SEs, which causes uncertainty in defining principals and agents in SEs.

Complex governance mechanisms within SEs lead to equally complex agency relationships, a phenomenon that aligns with Mitnick’s [87] foundational insights into agency theory. Mitnick’s research emphasized an institutional approach designed to capture real-world behaviors, shaping the core logic of agency theory by highlighting how institutions evolve to mediate and reconcile agency relationships [87]. Building upon this perspective, SAT is applied to SEs, thereby extending and refining traditional agency theory to more comprehensively account for the intricate agency relationships that characterize SEs.

Theoretical Model of Sustainability Agency

Under normal circumstances, principals prioritize CSR over profits, while agents focus on profit generation to sustain and enhance CSR activities. In this context, normal circumstances refer to a stable internal and external environment in which the survival and operations of SEs remain unaffected. However, during critical situations, these conflicts can become more pronounced and intensify. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, a crisis that threatened the survival of all industries, agents of SEs became more concerned with the survival of their organizations. To avoid bankruptcy, SE agents prioritized profitability, thereby further intensifying conflicts during such crises.

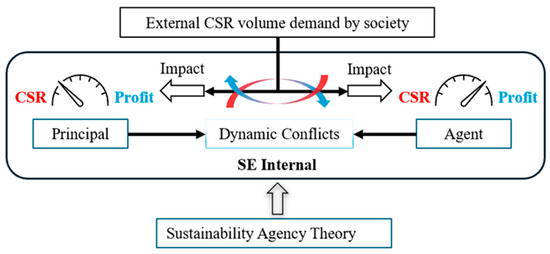

The conflict between agents and principals is also different in traditional enterprises and SEs. As for traditional enterprises, the conflict of interest between agents and principals can be understood as the conflict between activities directly and indirectly oriented towards profit. As for SEs, the conflict centers on the differing levels of importance that principals and agents place on the company’s profits and CSR. According to SAT, agents primarily focus on short-term profit-making to ensure the financial sustainability of SEs, whereas principals prioritize long-term social objectives. As the objective of roles in SEs is dynamic, this makes the conflict analysis more complex. Under normal circumstances, conflict exists between principals and agents. However, conflict may intensify during a crisis due to the worsening external environment. By applying SEs’ agency theory, this study aims to delve into these internal conflicts, offering a detailed analysis of the dynamics within SEs. The main contribution of this study is the investigation of agency conflict within SEs as an extension of traditional agency theory, providing a new definition of agency theory application within the context of SEs. The researcher has designed the SEs’ agency theory model in Figure 1 to reflect the internal conflict and its operation.

Figure 1.

Sustainability Agency Theory Model.

Building on the insights from the literature review, traditional AT cannot be applied to offer a comprehensive analysis of the relationship between principal and agent dynamics specific to SEs. Eisenhardt [94] identifies seven core assumptions underpinning agency theory: self-interest, goal conflict, bounded rationality, information asymmetry, pre-eminence of efficiency, risk aversion, and information as a commodity. These assumptions overlap, extending many new theories and articles [83]. Based on Muldoon et al. [95], traditional AT is difficult to apply in the context of SEs, or even social entrepreneurship more broadly, and they argue that a new framework is needed for more effective analysis. This study specifically foregrounds the issue of goal conflict and proposes a SAT that builds on traditional agency theory by emphasizing the dynamic goal conflict that exists in principals and agents in SEs.

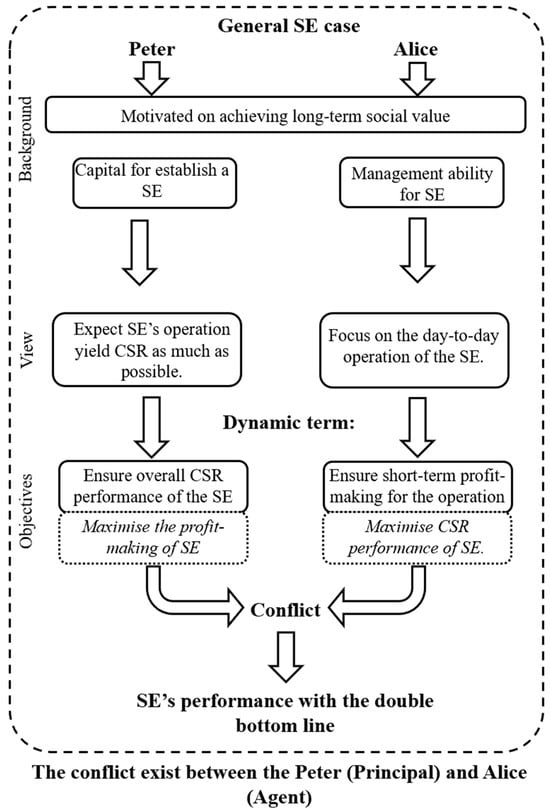

Based on SAT, SE members who instinctively want to achieve long-term social value are named as principals. On the other hand, SE members who are required to take actions to balance short-term profit-making objectives and social objectives are named as agents. Agents in SEs are more concerned about the survival and development of the company than principals. During crisis situations such as COVID-19, given the unpredictable nature of the pandemic, the imperative for managers to prioritize the interests of owners has become both more critical and more challenging [96]. This complexity is further exacerbated by resource constraints and the existential risks threatening organizational continuity. A clear explanation of this conflicting tendency in SEs requires extending traditional agency theory. In the context of SEs, all stakeholders share the common goal of achieving long-term social value. However, principals and agents exhibit different tendencies when it comes to prioritizing CSR or profit-making, particularly when agents consider engaging in business activities. This internal conflict stems from the challenge of balancing the pursuit of short-term profit maximization with the long-term goal of maximizing social value, as SEs must navigate the tension between financial sustainability and their broader social mission. Under normal circumstances, agents prefer to engage in more CSR activities after achieving profit, whereas principals tend to prioritize CSR initiatives from the outset. In times of crisis, this conflict increases as financial pressures force agents of SEs to do more profitable activities to ensure the organization’s normal operation. To better explain the SEs’ agent theory, the researcher gives an example of a usual situation and draws it in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Example of SAT conflict relationship between principals and agents.

In the example illustrated in Figure 2, Peter acts as the principal and Alice serves as the agent within an SE framework. Both aim to generate long-term social value and promote the sustainability of the SE. While Peter provides the capital and prioritizes reinvesting resources to maximize social impact, Alice, responsible for daily operations, focuses on maintaining profitability to ensure the organization’s short-term survival and continued operation. Although Peter recognizes the importance of financial viability, he emphasizes using surplus for broader social outcomes, whereas Alice concentrates on immediate financial stability. This divergence in objectives reflects an agency conflict, as defined by Sustainability Agency Theory (SAT). Peter values social impact over profit-making, while Alice views profit generation as instrumental to sustaining operations. The resulting misalignment leads to agency costs when the agent’s actions do not fully align with the principal’s expectations. This example clearly illustrates the principles of SAT. Of course, Peter’s role is not always that of a principal, as roles within SEs are inherently dynamic and can shift depending on the context. Peter and Alice are simply used as illustrative examples to demonstrate how SAT operates over a given period.

5. Dimensions of Sustainability Agency Theory

As for SAT, SEs have dual objectives and need to balance them, which creates a conflict between principals and agents in SEs. Moreover, the aim of SEs is to address various social issues, so the principals of SEs want to achieve long-term social value. In contrast, the agents of SEs pursue a balance between CSR activities and profit generation. The dynamics in SEs are mainly due to the changing objectives of profit-oriented activities and CSR activities. When agents engage in profit-making actions, these may conflict with the interests of their principals, resulting in tension. Therefore, this study examines seven different dimensions to explain the conflict dynamics within SAT.

5.1. Time Horizon Differences

Conflicts of interest arise between principals of SEs and managers of SEs with respect to the timing of the profitability of companies. Principals of SEs will focus on the use of the company’s profitability for long-term social value creation. However, agents may be more concerned with company profitability to ensure the normal operation of the company, leading to a bias in favor of short-term profit-making projects at the expense of long-term social value projects. In terms of SAT, the main reason for the conflict is the different perspectives of principals and agents. From the principals’ perspective, SEs should invest in activities that produce significant social benefits over time. This corresponds to the long-term social impact. In contrast, agents emphasize generating sufficient income or profit in the short term to ensure the organization’s financial sustainability. Tensions arise when short-term profitability exceeds the sustained investment needed to expand social impact.

Moreover, the external circumstances may also force members of SEs to switch between short-term interests and long-term social missions. As an example, an economic depression may force agents to prioritize short-term income as they ensure that the company survives successfully. Even though the CSR may require a longer-term focus, the profit-making often creates short-term pressures. These differing priorities can cause tensions, as decision-makers in SEs balance immediate viability with sustained social impact.

5.2. Resources Competition Conflicts

When SEs run several separate projects or provide multiple services, this is when conflicts can occur between principals and principals, or principals and agents. As for principals and principals, although all principals aim to maximize the overall social value of SE, the irrational allocation of resources may prompt individual project principals to prioritize securing resources for their own initiatives. These project principals may seek to protect or expand their share of resources, even when reallocating some of those resources to another project could generate a greater overall impact on the SE. In the principal–agent context, tensions emerge when limited financial resources cannot sustain all projects adequately. Given that SEs are driven by a social mission [97], decisions regarding resource distribution (e.g., funding allocation, staff allocation) are crucial [98].

As a result, the needs of individual projects may not always align fully with the organization’s broader objectives or resource constraints, potentially fostering competition and tension. Combining individual projects with total services, SAT can provide a deeper understanding of the dynamics within the organization and how this shapes social impact and financial sustainability.

5.3. Strategic and Operational Dimension

This dimension explores the conflict within SEs from two different perspectives, which are strategic and operational, combined with the SAT. From a strategic perspective, members are those who possess the authority to establish and guide the SE’s overarching goals, mission, and vision. For instance, strategic leaders decide to develop a new community project, thus directing the SE’s long-term social value. While many of these individuals can be deemed principals because given their emphasis on achieving sustained social objectives. By contrast, others adopt an agent role if they prioritize short-term profitability to satisfy financial requirements or balance social and financial objectives.

In terms of operational perspective, it focuses on those who are concerned with day-to-day activities and current tasks, often implementing strategic plans at a practical level. It is important to note that being an implementer of a strategy does not necessarily mean that all individuals are agents. In certain circumstances, such as when executing CSR initiatives without strict regard for profitability, implementers may also take on the role of principals by emphasizing social impact over short-term gains.

In terms of strategic-level conflict analysis, conflict can arise when some of the strategic leaders want to pursue aggressive growth strategies such as expansion of SEs through profit (Agents), while others prefer a more conservative approach that emphasizes the quality of the existing community (Principals). At the operational level, tensions surface in critical situations that threaten the SE’s survival. Even if strategic leaders adopt a new CSR strategy, frontline staff or managers may still prioritize short-term revenue generation to ensure the SE’s survival. These differing priorities often lead to conflicts between the strategic and operational levels.

5.4. Localistic and Societal Dimension

The localistic and societal dimension differentiates whether SEs concentrate on serving a particular local community or addressing broader social issues. A localistic SE addresses the specific needs of a small-scale, community-based organization, which usually has an in-depth understanding of local issues and resources. In contrast, a societal SE seeks to tackle wide-ranging societal or global challenges that extend beyond a single community. Therefore, localistic SEs tend to emphasize the depth of impact within the local area, whereas societal SEs aim to generate greater breadth of social value across multiple regions or populations.

Based on the SAT analysis, conflicts between localistic and societal SEs arise due to differing perspectives on the scale of social impact. The conflict can arise when deciding whether to prioritize activities that consolidate the SE’s existing local mission or to pursue broader expansion, similar to the strategic-level conflict described in the previous dimension. However, conflict can occur in more than one situation in this dimension. Tensions can arise when one group of principals wants to expand the scope of social values, while another group of principals may feel that the current community still needs more resources and is not fully compliant with the strategic plan. In addition, if agents also perceive local issues as more pressing and in need of more financial support in the short term, they may deviate from the intended broader social objectives, potentially giving rise to principal–agent conflicts.

5.5. Physical and Virtual Dimensions

The conflict concerning the physical and virtual dimensions revolves around the method of social service delivery and can be interpreted as occurring among principals. While some principals favor physical, face-to-face actions as a means of fostering stronger community ties, others advocate for an online delivery model to broaden the scope and reach of services. This divergence in preferred social service delivery methods inevitably generates internal tensions within principals and principals.

Another source of conflict arises between principals and agents when deciding how much investment should go into developing digital infrastructure versus maintaining physical service delivery. Because operating physical service delivery methods need physical space, staff presence, and additional logistical considerations, it typically requires more human and financial resources than an online model. Tensions emerge when allocating resources between developing digital platforms and sustaining physical service delivery.

5.6. Innovation Dimension

Within the innovation approach dimension, SEs address social challenges through novel methods, such as advanced technologies or innovative business models, and so on. In contrast to the relative stability commonly associated with traditional approaches, innovative solutions are often characterized by unpredictability and risk. Moreover, pursuing innovation requires considerable upfront investment, including research and development, staff training, and so on. This financial burden can intensify pressures on agents because they need to gain more profits in the short term. As a result, tensions between principals and agents may increase.

5.7. Moral-Hazard Agency Conflicts

A final dimension worth considering is the potential for moral-hazard agency conflicts within the framework of SAT. In the traditional view of AT, moral-hazard conflicts frequently arise, particularly in large firms or those with substantial cash flows [99]. In terms of SAT, agents are likely to sell products that cut corners in order to make short-term profitable revenues. For example, an agent may focus on increasing operational expenses or accelerating company expansion at the expense of maintaining the enterprise’s social mission. Such behavior can lead to mission drift, where products or services deviate from the organization’s intended social objectives.

Furthermore, SEs are often heavily reliant on external funding, such as support from investors. These external investors are interested in achieving long-term social value, which is equivalent to principals. However, geographical distances or inadequate access to operational data can impede the effective monitoring of these investments. As a result, agents may misrepresent or even exaggerate CSR achievements to secure additional support, thereby increasing the risk of moral hazard. Thus, even though SEs have a dual mission that focuses on social impact and financial sustainability, moral-hazard agency conflicts exist within SAT.

6. Limitations and Practical Implications

This study represents an exploratory extension of traditional AT into the context of SEs through SAT. While the framework offers theoretical insight, several limitations must be acknowledged.

Firstly, as a conceptual framework proposed for the first time, SAT has not yet been tested with samples. Future research is needed to assess its validity and applicability across different types of SEs, using diverse samples and methodological approaches. Designing empirical studies to evaluate the extent to which SAT captures principal–agent dynamics in varied organizational settings will be essential in strengthening the theoretical robustness and credibility of the framework.

Secondly, SAT proposes that conflictual relationships are conditional. There must be a principal and an agent within SEs. If SEs do not have distinct principals and agents, such as in the case of self-employed individuals, the applicability of SAT requires further exploration in future research.

In addition, SAT offers several important implications for the governance and management of SEs. It provides stakeholders in SEs with a conceptual tool for clarifying organizational tensions and can help them to better understand inherent tensions in hybrid organizational models. SAT can be applied to analyze inherent tensions arising from conflicting objectives within SEs across a variety of organizational contexts. Moreover, SAT illustrates the need to design governance mechanisms that ensure agents are incentivized to uphold the organization’s social mission alongside its financial sustainability. By clarifying the agency conflicts that arise between social and financial objectives, SAT equips SE stakeholders (e.g., managers, investors) with a clearer understanding of how divergent priorities may lead to mission drift or operational misalignment.

7. Conclusions

This article builds on traditional AT and extends its application to SEs. This research proposes SAT. The researcher defines the roles of agents and principals in line with the characteristics of SEs, addressing ambiguous definitions that exist in SEs. SAT provides a more detailed explanation of the inherent tensions that arise from balancing social objectives with financial sustainability.

In the context of SEs, the researcher defines that SE members who instinctively want to achieve long-term social value are named as principals. On the other hand, SE members who are required to take actions to balance short-term profit-making objectives and social objectives are named as agents. The conflict increases between principals and agents when actions taken by agents are more focused on profit-making objectives.

These short-term profit-making actions are contrary to principals that prioritize the social objective. Although the agent primarily seeks profit generation, this pursuit of profit serves as a means to achieve or maintain the overarching social objectives.

SAT contributes to the literature by offering a new theoretical perspective to examine agency conflicts within SEs. The novel framework is illustrated through conceptual modelling (Figure 1), supported by an applied example (Figure 2), and further developed through seven analytical dimensions that capture the multifaceted nature of principal–agent tensions in SEs.

As a purely theoretical study, this article necessarily faces certain limitations in scope and application. Future research is needed to assess its applicability across different types of SEs using diverse samples. Moreover, SAT is premised on the existence of distinguishable principals and agents within SEs. In cases where SEs operate without clearly defined principal–agent structures, such as self-employed individuals, the theoretical assumptions of SAT may not fully apply. In sum, this study contributes to both agency theory and SEs’ research by offering a context-sensitive approach to understanding dynamic conflicts within hybrid organizations. It provides a foundation for further theoretical refinement and practical application in SEs’ governance and strategy.

Author Contributions

The authors contributed equally to the development of this manuscript. Y.Y.: Conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation and editing; S.G.: methodology, supervision, writing—review; H.Z.H.: project administration, supervision, writing—review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research underwent rigorous examination by the DMP (Data Management Plan) and PIA (Privacy Impact Assessment) at Edinburgh Napier University, resulting in authorization for this research. Protocol No.: ENBS-2022-23-049. 31 August 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AT | Agency Theory |

| SE | Social Enterprise |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| SAT | Sustainability Agency Theory |

References

- Tykkyläinen, S.; Ritala, P. Business Model Innovation in Social Enterprises: An Activity System Perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 684–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, A.-C.; Santos, F. Inside the Hybrid Organization: Selective Coupling as a Response to Competing Institutional Logics. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 56, 972–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter Michael, E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating Shared Value: How to Reinvent Capitalism—And Unleash a Wave of Innovation and Growth. In Managing Sustainable Business: An Executive Education Case and Textbook; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 323–346. [Google Scholar]

- Huybrechts, B.; Alex, N.; Edinger, K. Sacred Alliance or Pact with the Devil? How and Why Social Enterprises Collaborate with Mainstream Businesses in the Fair Trade Sector. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2017, 29, 586–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, I.; Lyon, F. Beyond Green Niches? Growth Strategies of Environmentally-Motivated Social Enterprises. Int. Small Bus. J. 2012, 32, 449–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornforth, C. Understanding and Combating Mission Drift in Social Enterprises. Soc. Enterp. J. 2014, 10, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiselein, P.; Dentchev, N.A. Managing Conflicting Objectives of Social Enterprises. Soc. Enterp. J. 2020, 16, 431–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Moss, T.W.; Gras, D.M.; Kato, S.; Amezcua, A.S. Entrepreneurial Processes in Social Contexts: How Are They Different, If at All? Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 40, 761–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver Rasheda, L. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Social Enterprise Sector. J. Soc. Entrep. 2023, 14, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, C.; Jin, S. How Does Corporate Social Responsibility Affect Sustainability of Social Enterprises in Korea? Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 859170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, T.; Vaccaro, A. Stakeholders Matter: How Social Enterprises Address Mission Drift. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 143, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilburn, K.; Wilburn, R. The Double Bottom Line: Profit and Social Benefit. Bus. Horiz. 2013, 57, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, B.; Haugh, H.; Lyon, F. Social Enterprises as Hybrid Organizations: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith Wendy, K.; Gonin, M.; Besharov, M.L. Managing Social-Business Tensions: A Review and Research Agenda for Social Enterprise. Bus. Ethics Q. 2013, 23, 407–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. Equity Finance for Social Enterprises. Soc. Enterp. J. 2006, 2, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, S. Models of Social Enterprise in the Homelessness Field. Soc. Enterp. J. 2010, 6, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J.; Holdsworth, C.; Rasul, S.; Budree, A. The Role of Social Enterprises in Post Covid Recovery in Africa. Stud. Eur. 2022, 73–101. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, D.; Park, J. Local Government as a Catalyst for Promoting Social Enterprise. Public Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 665–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U.; Uhlaner, L.M.; Stride, C. Institutions and Social Entrepreneurship: The Role of Institutional Voids, Institutional Support, and Institutional Configurations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2015, 46, 308–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, R.; Blakey, C. Winter Always Comes: Social Enterprise in Times of Crisis. Soc. Enterp. J. 2022, 18, 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisan-Mitra, C.; Borza, A. Social Entrepreneurship and Corporate Social Responsibilities. Int. Bus. Res. 2012, 5, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariat, S.; Khamseh, Z. ‘Fruits of the Same Tree’? A Systematic Review of Corporate Social Responsibility and Social Enterprise Comparative Literature. In Corporate Responsibility, Sustainability and Markets; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 185–214. [Google Scholar]

- Cherian, J.; Sial, M.S.; Tran, D.K.; Hwang, J.; Khanh, T.H.; Ahmed, M. The Strength of Ceos’influence on Csr in Chinese Listed Companies. New Insights from an Agency Theory Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, T.; Minor, D. Ceo Power, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Firm Value: A Test of Agency Theory. Int. J. Manag. Financ. 2016, 12, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palakshappa, N.; Grant, S. Social Enterprise and Corporate Social Responsibility: Toward a Deeper Understanding of the Links and Overlaps. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 24, 606–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, N.; Calvo-Babío, F. Corporate Social Responsibility and Multiple Agency Theory: A Case Study of Internal Stakeholder Engagement. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1223–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen Michael, C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs, and Ownership Structure. In Economics Social Institutions: Insights from the Conferences on Analysis & Ideology; Brunner, K., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1979; pp. 163–231. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, E.; Yeh, C.-C.; Wang, L.-H. The Relationship between Csr and Performance: Evidence in China. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2018, 51, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Rodríguez, G.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R.; Wiseman, R.M. Has Agency Theory Run Its Course?: Making the Theory More Flexible to Inform the Management of Reward Systems. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2012, 20, 526–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra Shaker, A.; Gedajlovic, E.; Neubaum, D.O.; Shulman, J.M. A Typology of Social Entrepreneurs: Motives, Search Processes and Ethical Challenges. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Harjoto, M.A. Corporate Governance and Firm Value: The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 103, 351–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgstock, R.; Lettice, F.; Özbilgin, M.F.; Tatli, A. Diversity Management for Innovation in Social Enterprises in the UK. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2010, 22, 557–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alter, S. Social Enterprise Models and Their Mission and Money Relationships. In Social Entrepreneurship: New Models of Sustainable Social Change; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 205–232. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, A.; Yasir, M.; Majid, A. Is Social Entrepreneurship a Panacea for Sustainable Enterprise Development? Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2019, 13, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Mulgan, G. The Process of Social Innovation. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2006, 1, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawell, M. Social Entrepreneurship—Innovative Challengers or Adjustable Followers? Soc. Enterp. J. 2013, 9, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chell, E.; Spence, L.; Perrini, F.; Harris, J. Social Entrepreneurship and Business Ethics: Does Social Equal Ethical? J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 133, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, M.; Zeyen, A.; Krzeminska, A. Mission, Finance, and Innovation: The Similarities and Differences between Social Entrepreneurship and Social Business. In Social Business; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Omorede, A. Exploration of Motivational Drivers Towards Social Entrepreneurship. Soc. Enterp. J. 2014, 10, 239–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nga, K.H.; Joyce; Shamuganathan, G. The Influence of Personality Traits and Demographic Factors on Social Entrepreneurship Start up Intentions. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.-L.; Williams, J.; Tan, T.-M. Defining the ‘Social’ in ‘Social Entrepreneurship’: Altruism and Entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2005, 1, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, J.; Nyssens, M. Social Innovation, Social Economy and Social Enterprise: What Can the European Debate Tell Us? In The International Handbook on Social Innovation: Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 40–52. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, R. Rural Social Enterprises as Embedded Intermediaries: The Innovative Power of Connecting Rural Communities with Supra-Regional Networks. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aras, G.; Aybars, A.; Furtuna, O.K. Managing Corporate Performance: Investigating the Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance in Emerging Markets. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2010, 59, 229–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.; Katz, R. Is Social Enterprise the New Corporate Social Responsibility? Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons: Seattle, WA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius, N.; Todres, M.; Janjuha-Jivraj, S.; Woods, A.; Wallace, J. Corporate Social Responsibility and the Social Enterprise. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.; Stevenson, H.; Wei, J. Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Same, Different, or Both? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei-Skillern, J. Entrepreneurship in the Social Sector; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Korschun, D.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Swain, S.D. Corporate Social Responsibility, Customer Orientation, and the Job Performance of Frontline Employees. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S. The Economic Theory of Agency: The Principal’s Problem. Am. Econ. Rev. 1973, 63, 134–139. [Google Scholar]

- Panda, B.; Leepsa, N.M. Agency Theory: Review of Theory and Evidence on Problems and Perspectives. Indian J. Corp. Gov. 2017, 10, 74–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masulis Ronald, W.; Reza, S.W. Agency Problems of Corporate Philanthropy. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2015, 28, 592–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabou, R.; Tirole, J. Individual and Corporate Social Responsibility. Economica 2010, 77, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, J.; Fasan, M.; Nanda, D. Is Corporate Social Responsibility an Agency Problem? Evidence from Ceo Turnovers. SSRN Electron. J. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tirole, J. Corporate Governance. Econometrica 2001, 69, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Phan, H.V.; Vo, H. Agency Problems and Corporate Social Responsibility: Evidence from Shareholder-Creditor Mergers. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 90, 102937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, Y. Kindness Is Rewarded! The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Chinese Market Reactions to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Econ. Lett. 2021, 208, 110066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cespa, G.; Cestone, G. Corporate Social Responsibility and Managerial Entrenchment. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2007, 16, 741–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnea, A.; Rubin, A. Corporate Social Responsibility as a Conflict between Shareholders. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-L.; Cheng, H.-Y. Public Family Businesses and Corporate Social Responsibility Assurance: The Role of Mimetic Pressures. J. Account. Public Policy 2020, 39, 106734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B. Causal Effect of Analyst Following on Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Corp. Financ. 2016, 41, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, A.; Javakhadze, D. Corporate Social Responsibility and Capital Allocation Efficiency. J. Corp. Financ. 2017, 43, 354–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Kim, K.A. Corporate Governance in China: A Survey. Rev. Financ. 2020, 24, 733–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiser Brakman, D. Theorizing Forms for Social Enterprise. Emory Law J. 2013, 62, 681. [Google Scholar]

- Luke, B.; Verreynne, M.-L. Social Enterprise in the Public Sector. Metservice: Thinking Beyond the Weather. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2006, 33, 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.; Tang, J. Dilemmas Confronting Social Entrepreneurs: Care Homes for Elderly People in Chinese Cities. Pac. Aff. 2006, 79, 623–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvord Sarah, H.; Brown, L.D.; Letts, C.W. Social Entrepreneurship and Societal Transformation: An Exploratory Study. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2004, 40, 260–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss Todd, W.; Short, J.C.; Payne, G.T.; Lumpkin, G.T. Dual Identities in Social Ventures: An Exploratory Study. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 805–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman, P.; Whetten, D. Members’ Identification with Multiple-Identity Organizations. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 618–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.; Nicholson, G.; Shropshire, C. Directors’ Multiple Role Identities, Identification and Board Monitoring and Resource Provision. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2006, 2006, J1–J6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.; Grimes, M.; McMullen, J.; Vogus, T. Venturing for Others with Heart and Head: How Compassion Encourages Social Entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 616–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A. Institutionalizing Social Entrepreneurship in Regulatory Space: Reporting and Disclosure by Community Interest Companies. Account. Organ. Soc. 2010, 35, 394–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerawardena, J.; Mort, G.S. Investigating Social Entrepreneurship: A Multidimensional Model. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegner, M.; Pinkse, J.; Panwar, R. Managing Tensions in a Social Enterprise: The Complex Balancing Act to Deliver a Multi-Faceted but Coherent Social Mission. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 1314–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Mayer, J.; Lutz, E. Navigating Institutional Plurality: Organizational Governance in Hybrid Organizations. Organ. Stud. 2015, 36, 713–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Pinkse, J.; Preuss, L.; Figge, F. Tensions in Corporate Sustainability: Towards an Integrative Framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Vaseková, V.; Kročil, O. Entrepreneurial Solutions to Social Problems: Philosophy Versus Management as a Guiding Paradigm for Social Enterprise Success. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2023, 31, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, P.D.; Ho, M. How Opportunities Develop in Social Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 635–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Hockerts, K. Impact Investing Strategy: Managing Conflicts between Impact Investor and Investee Social Enterprise. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.M. A Positive Theory of Social Entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Ko, W.-W. Organizational Learning and Marketing Capability Development: A Study of the Charity Retailing Operations of British Social Enterprise. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2011, 41, 580–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridley-Duff, R.; Bull, M. Understanding Social Enterprise: Theory and Practice (Sample Chapter); Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bendickson, J.; Muldoon, J.; Liguori, E.; Davis, P. Agency Theory: The Times, They Are a-Changin’. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 174–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, M.; McMullen, J.; Vogus, T.; Miller, T. Studying the Origins of Social Entrepreneurship: Compassion and the Role of Embedded Agency. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2013, 38, 460–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S. Reciprocal Agency. J. Institutional Theor. Econ. JITE Z. Gesamte Staatswiss. 2001, 157, 246–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englmaier, F.; Kolaska, T.; Leider, S. Reciprocity in Organizations: Evidence from the UK. CESifo Econ. Stud. 2016, 62, 522–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitnick, B.M. The Theory of Agency: The Policing ‘Paradox’ and Regulatory Behavior. Public Choice 1975, 24, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Dorado, S. Building Sustainable Hybrid Organizations: The Case of Commercial Microfinance Organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 1419–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S.E. Review of How to Change the World: Social Entrepreneurs and the Power of New Ideas, Bornstein, David. Child. Youth Environ. 2005, 15, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, P.; Phillips, N.; Jarvis, O. Bridging Institutional Entrepreneurship and the Creation of New Organizational Forms: A Multilevel Model. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mswaka, W.; Aluko, O. Corporate Governance Practices and Outcomes in Social Enterprises in the Uk: A Case Study of South Yorkshire. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2015, 28, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diochon, M.; Anderson, A. Social Enterprise and Effectiveness: A Process Typology. Soc. Enterp. J. 2009, 5, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, C.; Chinnock, C. Governance Failure in Social Enterprise. Educ. Knowl. Econ. 2008, 2, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Agency Theory: An Assessment and Review. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muldoon, J.; Skorodziyevskiy, V.; Gould, A.M.; Joullié, J.-E. Agency Theory and Social Entrepreneurship: An Axe That Needs Sharpening. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M.A.; Arregle, J.; Holmes, R.M., Jr. Strategic Management Theory in a Post-Pandemic and Non-Ergodic World. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 58, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, S.; Sahay, A.; Hisrich, R.D. The Social—Market Convergence in a Renewable Energy Social Enterprise. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 270, 122516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulshrestha, R.; Sahay, A.; Sengupta, S. Constituents and Drivers of Mission Engagement for Social Enterprise Sustainability: A Systematic Review. J. Entrep. 2022, 31, 90–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McColgan, P. Agency Theory and Corporate Governance: A Review of the Literature from a UK Perspective; University of Strathclyde: Glasgow, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).