Abstract

In Cuba, coastal zone management is a matter of environmental priority. The Cuban State has legislated its protection mechanisms, actions, and instruments according to a high-hierarchical-rank legal norm. This article revealed the institutional frameworks and implementation strategies that support the socio-ecosystemic approach in coastal marine governance in the southeastern region of Santiago de Cuba, focusing on the management practices of integrated coastal zone management (ICZM) programs. Under the logic of ICZM principles, a scientometric, exegetical–legal study was carried out, with thematic content analysis, using the Driving Forces–Pressures–State–Impacts–Respond (DPSIR) framework. The methodology to meet the objectives was based on three analytical stages that generated scientific proposals for implementing the socio-ecosystemic approach in adaptive coastal governance practices. As a result, it is demonstrated that this approach has a scientific and legal proposal in Cuba, and its dynamics in coastal management programs are revealed. This study indicates that the logic of the DPSIR framework provides a propositional platform that helps structure the fundamentals of the proposed approach with reference to objectives and responses of coastal marine governance in Cuba.

1. Introduction

The socio-ecosystemic approach revolves around an integrated land, water, and living resources approach. It facilitates the sustainable provision of ecological services equitably and where ecological and social dimensions interact on a continuum and at different scales [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. This approach offers opportunities for sustainability and is positively addressed by several Sustainable Development Goals. Consequently, governance foundations are required to ensure ecological objectives and multi-sectoral integration, especially when coastal zones are the focus of analysis [8,9,10,11,12].

In general terms, governance [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22], as recognized by the UN Commission, “(…) is the sum of the many ways in which individuals and institutions, public and private, manage their communal affairs. It is a continuous process through which conflicting or diverse interests can be accommodated, and cooperative action can be taken. It includes formal institutions and regimes empowered to enforce the law and informal arrangements that individuals and institutions have agreed to or perceive to be in their interest” [23].

Governance has two fundamental functions for coastal zone management that directly affect the socio-ecosystemic approach. First, it plays a protective role, so explicit measures must be designed to ensure the ecosystem’s ecological, social, and economic sustainability through appropriate governance approaches [24,25]. Secondly, it improves coordination mechanisms between the different levels of administration and social interests [26,27].

Several studies emphasize the importance of approaching coastal zone management from a socio-ecosystemic perspective [4,7,21,28,29,30,31]. Experts increasingly call for developing a governance framework for these coastal ecosystems with this approach as the backbone [30,32,33,34,35]. As a result, it has become a central paradigm of coastal marine resource management policy [6,36,37,38,39,40,41,42].

This approach from its conception [2,6,7,43,44,45] has been implemented at the international level for several years; however, in Cuba, it is legally implemented in Law No. 15 May 2022 [46]. However, its regulation is circumscribed to the ecosystemic aspect as a strategy for the integrated management of natural resources.

The determination of this legal perspective opens a significant epistemic gap. It raises several questions: How can we find ways to match the dynamics of institutions with the dynamics of ecosystems to achieve mutual social–ecological resilience and better performance? How can we synergize complex and dynamic ecosystems, adaptive governance practices, and institutions? [47].

This marks a relevant path for environmental management in Cuba, from a recently approved norm that defines an ecosystemic approach to a challenge of socio-ecosystemic integration [48]. Coastal marine ecosystems, which are the object of analysis in this research, do not escape from this scenario.

The issue has been so relevant in Cuba that the 2022 Decree Law No. 77 on Coasts [49] was approved, repealing Decree Law No. 212 of 2000. At the same time, the set of mechanisms, actions, and instruments to be applied in the coastal and protection zones were improved from an ecosystemic approach, as recognized in the legal norm. With this legislative action, the Cuban State reaffirms its legislative harmony with Latin America and the Caribbean countries with some legal coastal management standards [50].

However, implementing the new Cuban coastal standard requires advancing toward higher levels of adaptive marine–coastal governance. This will require improving the frameworks and strategies that involve communities, institutions, and state and private enterprises in coastal socio-ecosystems [51].

There are few recognized studies in the literature of international relevance on this approach in Cuban ecosystems [29,48,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. There are few analyses in this geographic setting on how to organize and help support management decisions from a socio-ecological perspective. In addition, new challenges are imposed by new legal regulations.

Since the enactment of Law No. 150 of 2022 and Decree Law 77 of 2022 and their regulations, essential questions have been raised about their implementation. This study aims to reveal the current status of frameworks and strategies in integrated coastal management, identifying critical nodes. It is based on management studies in the southeast of Cuba to advance national coastal marine governance. This research answers the following scientific questions: How will the socio-ecosystemic approach be implemented in the adaptive coastal management practices in Cuba; and what interpretative and application challenges will the coastal zone manager face when approaching the dimensions of the socio-ecosystem from the structural, organizational, and process points of view, and in the temporal and spatial scales? These are the initial premises that set a scientific debate in Cuba and that it is pertinent to address in this material.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methods

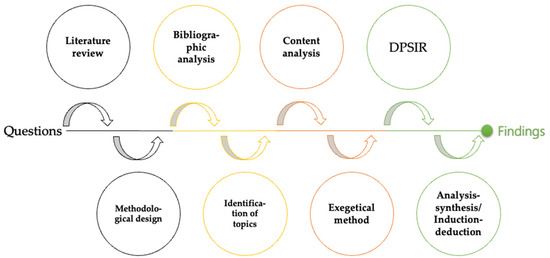

A descriptive type of research was carried out. Mixed methods of scientific research were used. Qualitative techniques allowed a deeper understanding of the object of study. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Dynamics of the research process.

Our scientific pathway follows the central paradigm of integrated coastal zone management and is consistent with the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment [59].

This research was configured in three stages, which are described below:

Stage I: Study the ontological and legal conceptions of the socio-ecosystemic approach in Cuba and its translation into coastal management practices. This stage includes:

- Scientometric study [60,61]: The bibliometric analysis method was used to identify the number of scientific articles on ecosystem-based management. The Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) databases were reviewed, considering articles published between 2000 and 2024. The keywords used were: “socio-ecological system” and “ecosystem-based management”. A total of 28,493 publications were identified within the selected years. Subsequently, the search was refined to the publications published in these databases on the reference approach in Cuba and organized by type of socio-ecosystem addressed. Ten publications associated with the defined search engines were identified.

Finally, the selected publications were analyzed according to the following criteria: (1) define the type of ecosystem and/or socio-ecosystem management addressed; (2) adopt a multifaceted or complex perspective of the approach, integrating ecological, social and governance systems; and (3) the articles must be widely accepted and referenced as leading publications in the field of socio-ecosystem management. This last criterion was evaluated based on factors such as the number of articles published by the authors on the topic and the citation frequency of the article.

The review of the definitions offered in the articles assessed produced three general frameworks that ontologize the approach and three fundamental indicators for a clear vision of the frameworks that support it in Cuba. The criteria of García, S.M. [62] and Rees, H.L. [63] were taken as a reference for the grouping.

- Exegetical–legal method: It evaluated the technical–legal quality of the current Cuban legislation regulating the ecosystem approach and its impact on governance management in the coastal zone. The analyses were focused on the formal and substantive points of view. The exegetical diagnosis focused on the conception of this approach in the legislation, its fundamental elements, its form of implementation, and scales of application, with special incidence in coastal zone management and the manifestations of legal gaps, antinomies, and legal ambiguities. In addition, an illustrative table was drawn up with all the current legislation consulted. Their objectives, sectors, and application scale were presented. The technical analysis of the bill was carried out based on Manuel Atienza’s scientific foundations [64].

- Thematic content analysis [65]: was used to determine coastal management programs, specifically in their management dynamics and the specific criteria of socio-ecosystem-based management, as proposed by the Cuban scientific doctrine and current legislation. Sixteen ICZM programs in the southeastern region of Santiago de Cuba were reviewed [66]. The Center for Multidisciplinary Studies of Coastal Zones (CEMZOC) of the University of Oriente, Cuba, designed and proposed these programs. They have different scopes and levels of implementation. In this study, their conception and design were analyzed; their implementation in the area was not evaluated because it was not the subject of this study. The programs analyzed were selected based on a purposive sample, for which an observation guide was prepared, which took into account (a) the characterization of the ecosystem, (b) assessment of ecosystem connections and their dynamic nature, (c) integrated and adaptive management dynamics, (d) identification of temporal and spatial scales, (e) use of scientific knowledge, (f) participation of key stakeholders, (g) sustainability criteria, (h) consideration of ecological integrity and biodiversity, (i) appropriate monitoring, (j) consideration of cumulative impacts, (k) presence of the precautionary approach, (l) the role of humans in the ecosystem, and m) incidence of the ecosystem approach in management planning. (See Appendix A: Content analysis guide).

These ICZM programs have emerged from the Master’s Program in Integrated Coastal Zone Management, taught at the Universidad de Oriente by CEMZOC. This Master’s Program has played an essential role in coastal management in the country’s southeastern part. It works in the training of coastal managers with a holistic, interdisciplinary, and multisectoral vision aimed at the elaboration and execution of plans, programs, and integrated projects for coastal zone management. Endorsements of introducing results in the southeast of Cuba accredit its scientific proposals. It has held the status of Master of Excellence by the National Accreditation Board of the Ministry of Higher Education of the Republic of Cuba since 2022.

In addition, the perspective of the Master’s work and its contribution to the territory’s government with its proposals are based on institutional agreements between the Universidad de Oriente and the government. This was expressed in the Agreement signed on 27 January 2023, which approves the Territorial Council for coordinating Science and Postgraduate actions to confront climate change in the eastern region of Cuba (COTECC). One of its main objectives is the coordinated, systemic, and comprehensive design of science and postgraduate actions to address climate change in the country’s eastern region in accordance with the current policy of the Cuban State and taking into account the particularities of this territory. In addition, there are more than 11 institutional agreements and science and innovation projects between CEMZOC and the government, which guaranteed the introduction of the results achieved.

Stage II: Evaluation of the application of management based on the socio-ecosystemic approach in coastal management programs in the southeastern region of Santiago de Cuba. This second stage includes:

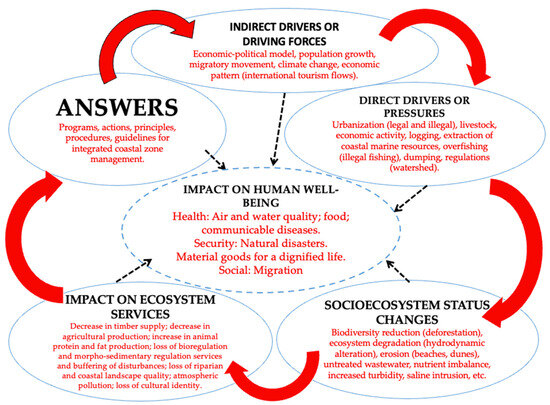

- DPSIR Framework: This framework was used to structure and facilitate the interpretation and analysis of environmental information. Socio-ecosystemic management in coastal zones has a marked holistic approach. Analyzing an ecosystem in terms of the stresses to which it is subjected indicates us to identify the driving or driving forces (D) that directly or indirectly affect the ecosystem, that is, an established social need that represents a factor and a social force that can induce changes in the state of the environment. Pressures (Ps) are how the driving forces interfere with and disrupt the system. The State (S) configures the combination of physical, chemical, and biological conditions of the environment in a given area. It is affected by the pressures and eventually modified in its environmental conditions. Impact (I) corresponds to the effects resulting from the change in the state of the ecosystem. Response (R) is a social action related to an environmental problem or a perceived risk [67].

The quantification of the pressures was based on a review of the reports available in the database of the National Office of Statistics and Information of the Republic of Cuba, in its bulletins Environmental, Economic, Social, and Territorial Panoramas, from 2015 to 2024 (accessible at: https://www.onei.gob.cu/, 3 December 2024). The databases of the National Institute of Hydraulic Resources (accessible at: https://www.hidro.gob.cu/, 3 December 2024), of the Ministry of Science, Technology and Environment (accessible at: https://www.citma.gob.cu/medio-ambiente-3/, 2 December 2024), and the cartographic database of the Centre for Multidisciplinary Studies of Coastal Zones of the University of Oriente (accessible at: https://www.cent.uo.edu.cu/cemzoc-uo/, 30 November 2024) were also accessed. The proposed analysis was carried out from 2020 to 2024.

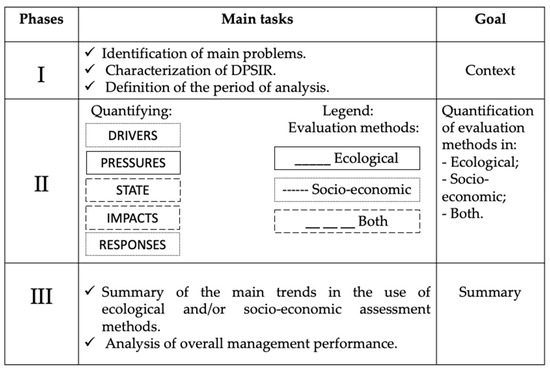

The methodological configuration of the structured framework for the DPSIR proposed by Nobre A.M. [11] was assumed and adapted for this analysis in Cuba, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Phases of the DPSIR study.

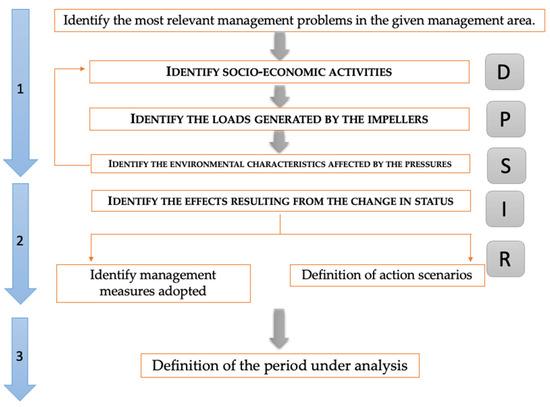

The objective of phase 1 was to define the scope and objective of this scientific study. As shown in Figure 3, this included: (a) the identification of the most relevant management problems in the given management area; (b) identification of management measures and action scenarios; and (c) definition of the period of analysis.

Figure 3.

Delimitation of the scope and objective of phase I.

Phase 2 focused on the configuration and synthesis of the DPSIR framework.

Phase 3 quantified the net values of the coastal management program analysis, building on the quantification of the phase 1 objectives. The inferential and analytical foundations were adapted to coastal marine spaces in all phases. They provided a holistic analysis, referencing the reports on the state of the coast offered by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessments (MEAs) [68].

Stage III: Recommendations for implementing the adaptive governance of the coastal socio-ecosystem in Cuba. In this stage, a set of recommendations was designed, based on induction–deduction and analysis–synthesis, to improve the socio-ecosystemic approach to coastal adaptive governance in Cuba. This enabled the establishment of a framework that organized the relevant variables identified in the theories and empirical research.

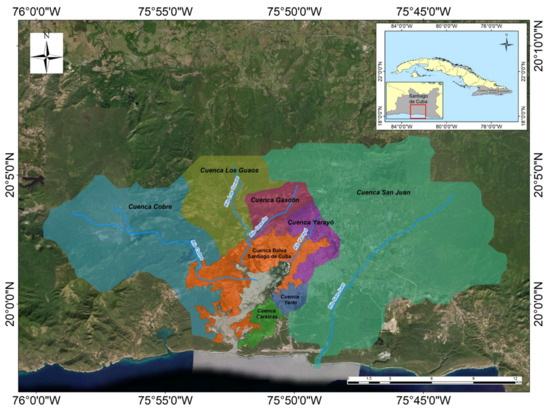

2.2. Study Area

Cuba is an island nation located in the Caribbean Sea. Cuba’s geographical location is 19°49′ and 23°16′ (north latitude) and 74°08′ and 84° 57′ (west longitude) of the Greenwich meridian, which places it north of the Caribbean Sea and south of the Tropic of Cancer. It has a surface area of 109,884.01 km2. Of this, 3126.41 km2 make up adjacent keys and 106,757.60 km2 make up the mainland area [69]. The island of Cuba is considered the largest of the Antilles because of its surface area.

This research focused on the southeastern region of Cuba (Figure 4). According to the administrative political division of the territory, this region is made up of three provinces. Table 1 below lists some of its characteristics as of December 2024.

Figure 4.

Localization of the study area.

Table 1.

Characterization of the study area.

The Republic of Cuba is an archipelago made up of more than 1600 islands, islets, and keys, the largest of which is the island of Cuba. It is also made up of four island groups: Los Colorados, Sabana—Camagüey (Jardines del Rey), Jardines de la Reina, and Los Canarreos. The latter is considered the most important because it contains the Isle of Youth, second in extension after the island of Cuba [69].

Cuba has a rather complex geography. On the island of Cuba, there are ancient rocks from the Jurassic and Cretaceous, especially in the mountainous areas, and from the Paleogene to the Quaternary in the rest of the territory. The island of Cuba has 5746 km and the Isle of Youth has 327 km of coastline, and very irregular coasts with varied and remarkable accidents. There are more than 280 beaches. The maximum width of the island of Cuba is 191 km, and the minimum is 31 km. The island has a predominantly warm, tropical climate, with a rainy season in the summer. The most notable variations in temperature and precipitation are associated with cold fronts, hurricanes, the altitudinal zone, and the contrasts of the relief [69].

As of 31 December 2023, the resident population was 10,055,968 U [70]. It has 15 provinces and 168 municipalities. Of the latter, 92 are coastal municipalities, representing 54.8% of the total.

As an archipelago, it is vulnerable to the impacts of extreme hydrometeorological phenomena, such as hurricanes, strong winds, rain, droughts, landslides, and coastal flooding, among other threats aggravated by climate change in the region [71,72,73].

3. Results

3.1. Results of Verifying Scientometric and Ontological Elements of the Socio-Ecosystemic Approach for the Cuban Environment

3.1.1. Scientometric Elements

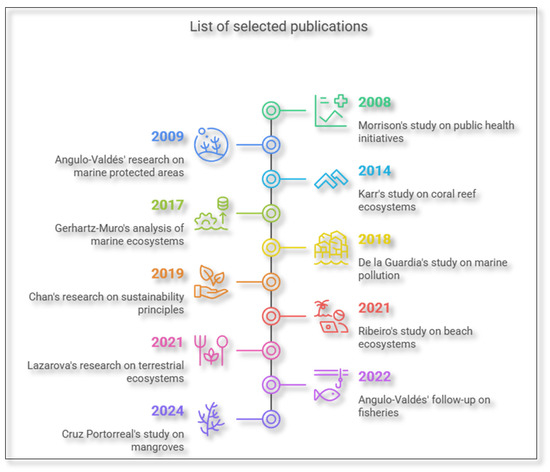

Based on the search criteria in the world’s two most prestigious bibliographic databases, SCOPUS and the Web of Science, ten scientific articles on ecosystem management in Cuba were found. The main areas of study they focus on include marine protected areas, coral reef ecosystems, beach ecosystems, soil ecosystems, mangrove ecosystems, and marine ecosystems (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

List of selected publications.

The analysis of these publications shows that three articles define ecosystem-based management and one the socio-ecological system. Eight scientifically assume the multifaceted or complex perspective of the approach, and other authors cite six at the national and international levels in the two databases. The articles with coastal marine ecosystems as their object of analysis meet the three selection criteria. The article by Angulo-Valdés, 2009 [55], enjoys greater visibility and impact (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Sample analysis of selection criteria.

3.1.2. Ontological Element

Analyzing each of the concepts provided by the authors and following the conceptual methodology offered by García, S.M. [62] and Rees, H.L. [63] revealed that socio-ecosystemic management in Cuba includes the three frames of reference described by the latter authors (see Table 3).

Table 3.

General frameworks that ontologize ecosystem management in Cuba.

Similarly, it was confirmed that the definitions provided emphasize the measurable characteristics of the structure or function of socio-ecological systems, grouping as evidenced in Table 4.

Table 4.

Key indicators supporting socio-ecosystem management in Cuba.

3.2. Legal and Institutional Aspects of Socio-Ecosystem-Based Management for the Cuban Environment

For the first time, a law in Cuba defined the ecosystem approach as a natural resource management strategy in its legal system. This law, called Law No. 150 of 2022, “On the system of natural resources and the environment”, in its Title III, aimed at regulating section 19.2, “The organization and operation of the system of natural resources and the environment”, recognizes this approach.

The legal norm, in an exhaustive manner, states that its application will imply: “(a) recognition of the structure and function of ecosystems and their direct relationship with the goods and services they provide to local communities, society and the ecosystem itself; (b) the use of appropriate scientific methodologies and is oriented on the levels of biological organization, covering the essential processes, functions, and interactions between organisms and their environment, based on critical thinking; and (c) the recognition that human beings, with their cultural and community diversity, are an essential component of ecosystems” [46].

It is novel that this approach will be developed based on recognizing the quantitative value and ecosystemic complexity, as well as cultural, political, economic, ethical, and socio-community interweaving. According to the law, all this is in harmony with the protection of biological diversity and natural heritage. In addition, measures should be implemented according to their quantitative and qualitative durability and renewable character. Consequently, the interdependence between ecosystems, natural resources, and other environmental elements to avoid, whenever possible, unnecessary or harmful reciprocal interference should be considered. And, finally, sustainability in their use should be ensured [46].

The ecosystemic approach in the framework of this law has a scale of application that is not only substantive, but also institutional. This was evidenced in the new conception of how the Cuban State has configured protecting a healthy and balanced environment as a constitutional right regulated in Article 75 of the Constitution. A Natural Resources and Environment System is configured in the law. Understood as the set of institutional, legal, and regulatory subsystems that manage natural, renewable, and non-renewable resources, the internal interaction between them and the environment is understood as the complex relations of the interrelation and interdependence established between natural resources and the elements to guarantee sustainable development [46].

Its management is recognized with a coherent institutional and normative vision. The Ministry of Science, Technology, and Environment of Cuba will act as the governing body, which is why it evaluates and controls the performance of natural resource users in accordance with the instruments of environmental policy and management. One of the law’s guiding principles is the decentralization of national environmental management. In this sense, the decision-making process will consider the territory’s conditions and the approach to local bodies, applying an ecosystemic approach.

This law provides substantive elements for the protection and sustainable use of natural resources, the environment, and natural heritage. It incorporates the environmental dimension into economic and social development plans within the established deadlines. It promotes greater multidisciplinary, intersectoral, and citizen participation in implementing other policies linked to natural resources or environmental management and quality. It is, therefore, the country’s environmental framework law.

For this reason, the promulgation of Decree Law No. 77 of 2023, “On Coasts” and its Regulations, Decree No. 97 of 2023, systematically assume that integrated coastal management is a tool for administration and control, whose purpose is to organize activities and prioritize environmental and socioeconomic interests, in which the particularities of the ecosystems present within a region, a sector or a locality are taken into account to direct the sustainable development of the territories.

The reference legislations and others that have an impact on our object of study, Table 5, revealed the following technical legal problems, which transcend the proper implementation of legal norms:

Table 5.

Main legislations in force in the country that affect coastal management.

- (1)

- It is omitted in the systematic framework law that the coastal marine ecosystem is an area with special regulations, specifically of high environmental significance and historical–cultural importance, as provided by Decree Law No. 331 of 2015. This last norm classifies it as such because it is a delimited territory with high fragility and vulnerability of its natural, ecological, and historical–cultural values, which before present or future actions of economic and social development or with a high degree of alteration and degradation by past actions, compromise sustainable development or lead to the loss of its patrimonial character. This aspect should have been reaffirmed by the hierarchy of Law No. 150 and its role in the current Cuban legal system.

- (2)

- Coastal zone management is fundamentally carried out under the Integrated Coastal Management Plans, but the legal norms do not define the regulatory structure of such a document. A very open formula is used, which is described in the following terms: “It includes action plans to contribute to the sustainable economic and social development of the territory under an ecosystemic, integral, and multi-sectorial approach, taking into account the relationship of the coastal zone with the tributary watersheds, with actions that maintain the environmental flow that guarantees the permanence of the ecosystemic goods and services provided by the watershed”. In addition, from the conceptualization of this instrument, in Article 2 of Decree No. 97/2023, the legislator omitted that it is a management tool and only circumscribed it to the administration and control of the watershed.

- (3)

- The legislation states that the Integrated Coastal Management Plan is integrated into the Local Development Program. However, a review of the legislation that articulates the latter in the country, Decree No. 33/2021, reveals the total omission of this coastal zone management tool.

- (4)

- Diversity of agencies of the Central Administration of the State that, from the framework law, have competencies in the management of marine and coastal ecosystems. The Ministry of the Food Industry will regulate hydrobiological resources’ sustainable use and management. The Ministry of Food Industry and the National Institute of Hydraulic Resources coordinate and implement actions to mitigate and restore the detrimental effects caused by the functional relationship between freshwater and marine ecosystems. The Ministry of Transportation establishes regulations so that transportation activities, civil navigation in maritime waters, and port activities are carried out, minimizing the damage to marine and coastal ecosystems, and demands the execution of recovery or repair actions when appropriate. In addition, the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Environment is assigned other responsibilities in the coastal zone and its protection zone, regulated in Article 55 of Law No. 15.

In addition, Decree Law No. 77 expanded the number of agencies involved in coastal management to include the following: the Ministry of Agriculture, the Ministry of the Revolutionary Armed Forces, the Ministry of the Interior, the Ministry of Tourism, the Ministry of Public Health, the National Institute of Hydraulic Resources, the National Institute of Territorial Planning and Urbanism, the Provincial Government of People’s Power, and the Council of Municipal Administration.

This leads to an overlapping of competences in the implementation of coastal legislation, with implications for regulatory complexity and institutional articulation.

3.3. Configurative Elements of the Socio-Ecosystemic Approach in ICZM Programs in the Southeastern Region of Cuba

The configurative elements of the socio-ecosystemic approach in ICZM programs were revealed. First, a summary table of relevant aspects was made for the general understanding of the analysis carried out. It is essential to know which programs were identified, their validity over time, and the bodies, agencies, or entities involved in the management of the program in general. The above is plotted in Table 6 below.

Table 6.

List of coastal management programs in the southeastern region of Santiago de Cuba.

The analysis showed that 100% of the coastal management programs define key issues, general objectives, specific objectives, key actors, goals, actions, and responsible parties for their implementation and development.

In their management dynamics, all the programs followed the logic of characterizing the ecosystem in three components: physical–natural, socioeconomic, and legal–administrative. This is due to the emphasis on the training of coastal managers in Cuba of Barragán’s scientific proposal [80], already extended throughout the country [81]. This has been possible thanks to the role played by the Ibermar Network in establishing a platform for interaction/coordination in the Ibero-American space for the exchange of knowledge and experiences oriented toward integrated coastal management [82].

A total of 56.2% of the analyzed programs valued ecological connectivity in management. This was evidenced, for example, in actions such as the reforestation of the coastal strip with vegetation that act as a barrier against floods (Seagrape, mangroves); planning strategies for plant and animal repopulation to facilitate the rapid recovery of biodiversity after a flood; establishing grazing areas without displacing native vegetation; classifying maturity stages according to the time of year and shell size [83]; determining the male-to-female ratio for each season; and coastal line reforestation [84].

Regarding integrated and adaptive management dynamics, one-hundred percent recognized multisectoriality in their actions, and only 68.7% defined actions to assess the effectiveness of socio-ecosystemic management practices. The latter was revealed in actions such as evaluating the changes produced by ICZM program actions in the selected key issues, determining deficiencies in the selected actions, the municipal watershed council monitoring compliance with the actions and assessing their relevance [85], and accountability of central-state administration agencies on coastal protection measures.

All the programs studied identified temporal and spatial scales in management. It is relevant that the study of the spatial scale was evidenced with new scientific GIS techniques, such as QGIS and satellite images using remote sensing [84,85]. The temporal scale for developing management actions was between 3 and 5 years.

Similarly, 100% used scientific knowledge with appropriate methodologies for the approach, as revealed in the equation used by the State Forest Service for the calculation of the viscosity index (IB) (SEF, 2022) [85]; command Simulate water Level Rise/Flooding [85]; Environmental Standard for Surface and Coastal Water Quality; execution of a geological engineer profile; studies conducted during two years in 104 stations of the Sabana-Camagüey Archipelago established a relationship between environmental variables and Cuban seagrasses; Environmental Quality Index in Tourist Beaches—ICAPTU; guidelines of the Normative Impact Analysis Memory (NIAM) [86]; and Tide Tables issued by the Nautical Cartography Agency, among others.

It was also noted that all the programs recognized the participatory role of key stakeholders in management. The observation made was predominant that this parameter was a transversal axis of the socio-ecosystemic management process.

Illustrative was that 81.2% of the programs designed indicators to measure ecological sustainability under the logic of being measurable characteristics of the structure, composition, or function of coastal ecological systems [25]. This was evidenced in the water footprint, foresightedness index [85], environmental health, water stress, sustainable waste management, coastal impact minimization [87], coastal erosion index, air quality [86], and ecosystem health [88], among others.

Similarly, 81.2%, as a logical consequence of the above, identified ecological attributes in the management programs studied, such as community structure, energy flow, interspecific relationships, vegetation structure, and dynamic ecosystem.

Seventy-five percent recognized the socio-ecosystemic services; based on this, they configured management actions, such as informing authorities, residents, community leaders, and other key actors of what the minimum catch size would be; designing projects to monitor sediment and nutrient variation about seagrass development; locating signs indicating the rules for beach use, existing zones, restrictions, prohibitions, and bathing schedules; making visible the areas and conditions that represent a risk for the user; locating buoys that delimit the swimming area; and providing the location of flags that announce or indicate the prohibition or restriction of entry when the dangerous conditions of waves, structures on the beach, or other risks exist.

It is remarkable how all programs recognized monitoring as a management action. This was evidenced in actions such as monitoring will be carried out at random points in the middle and lower parts of the San Juan watershed, evaluating abrupt changes in the decline in forest species, monitoring population density in different localities, monitoring the spatial and temporal variations in the size structure; expanding actions to monitor the volume of sediment impacting coastal ecosystems in the Guaos-Gascón watershed in the city of Santiago de Cuba; tours for the environmental monitoring of ICAR; and the location of ecological problems on Chivirico beach.

A total of 68.7% of the programs designed actions to evaluate the cumulative impacts on the ecosystems under management. They highlighted actions such as updating management models based on the analysis of potential climate impacts expected for the area; establishing long-term strategies for watershed management considering the effects of climate change (sea level rise, intensification and recurrence of drought periods, etc.); and strengthening surveillance in the council’s territories to prevent the reoccurrence of vulnerabilities.

All programs revealed a precautionary approach; however, only 25% shifted the burden of scientific proof to the activity’s proponents, and 68.7% designed preventive actions in the face of uncertainty. All programs recognized humans’ role in the coastal ecosystem under analysis.

It was revealed that 43.7% designed actions to identify financial and/or economic resources for management. However, more than 80% defined procedural actions for decision-making with this approach, and actions to identify institutional resources for decision-making were observed.

3.4. Dynamics of the Socio-Ecosystemic Approach in Coastal Management Programs in the Southeastern Region of Santiago de Cuba

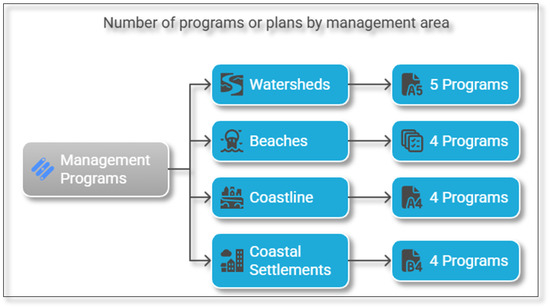

The application of phase 1 of this study allowed us to identify that all the management programs analyzed concretize their management problems. Their correspondence with the operational dimensions proposed by Barragán [89], which are more useful for the analysis of a coastal management problem, namely intensity, scope, novelty, urgency, complexity, and concreteness, is noteworthy. This study identifies four fundamental management areas: watersheds, beaches, coasts, and human settlements. Figure 6 quantifies the number of programs that address these areas.

Figure 6.

Number of programs or plans by management area.

The dynamics of the programs were specified in management measures and the definition of action scenarios; this is summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Management measures and definition of action scenarios.

Applying phase two reveals each of the elements that energize the DPSIR framework, Figure 7.

Figure 7.

DPSIR synthesized with the Millennium Assessment model.

As part of the quantification of the evaluation methods, part of phase 2, it was revealed that 56. 25% contemplate ecological evaluation methods, such as habitat evaluation, habitat classification, ecological systems classification, predictive systems, physical-chemical evaluation methods, Recreational Environmental Quality Index (REQI), Environmental Quality Index for Tourist Beaches (EQITB), ecosystem health, forest cover index, water analysis, bay morphology, homogeneous statistic zone method (ZEH), total dissolved solids (TDSs) behavior, Sentinel Water Index, and erosion–accretion rate.

A total of 18.75% used economic evaluation methods, the main method being the economic valuation of ecosystem goods and services (VEBSE). On the other hand, 25% used variants of both evaluation methods.

4. Discussion

Cuba has set an important challenge for adaptive management in its coastal zones by expressly recognizing the ecosystem approach in its legislation.

Although there is no international consensus on its definition, the socio-ecosystemic approach is accepted in the scientific community in recognition of the complexity and the relationship between species within ecological systems. In addition, human activities that impact ecosystems are also managed, and these effects are taken into account when making management decisions [1,24,25,26,27,90,91].

This is why it has been said to be an interdisciplinary approach. It is capable of balancing social, ecological, and governance principles under the synergies of temporal and spatial scales in each geographical area, all this with the aim of the sustainable use of natural resources. This type of management is more realistic and promising for addressing the complexity of ecosystems [27,92,93,94].

The first conclusion that can be drawn is the scarce scientific production in journals indexed in the WoS and SCOPUS on the subject of research, despite the fact that it is an incredibly fruitful and scientifically very-productive line of research worldwide. It is a field of research of very recent legal recognition in the country, which has experienced exponential international growth in the number of contributions in recent years.

The Cuban publications reveal a plurality of authors. The principal author is not always Cuban. It is worth mentioning the collaboration or joint work with international institutions to achieve the results revealed in the publications. Scientific institutions from Belgium, the United States of America, Brazil, Colombia, and Canada stand out.

In analyzing the foundations that shape this approach, the reviewed studies emphasize operational frameworks, such as participatory governance or adaptive management [62]; others are anchored in the normative framework, weighing the objectives of the approach [95]; and others emphasize more the procedural decision-making process [96]. However, the results of several of the studies suggest [5,39,61] that the social-ecological approach is often presented as more realistic and promising to address ecosystem complexity [3]. It emphasizes the ability to observe and interpret the essential processes and variables of ecosystem dynamics to develop the social capacity to respond to environmental feedback and change. This approach can integrate four subsystems: (i) resource systems, (ii) resource units, (iii) governance systems, and (iv) users [6].

The bibliographic mapping of the Cuban doctrine marks the ontology of the approach analyzed in three well-delineated theoretical frameworks. The cognitive one is determined by considering that this type of management combines ecological, social, and economic considerations to achieve the sustainable use of natural resources. On this basis, principals are defended in this type of management. In other words, the science-based approach, long-term objectives, monitoring, human beings in nature, and values should be observed. In only two publications [48,51], the need to observe the principles of partnership and citizen participation in management is revealed.

The standard is circumscribed to defining short-, medium-, and long-term objectives. This ensures the preservation of future conditions.

Our operation, based on the definition of management actions, ensures the levels of ecological organization, temporal and spatial scales, the precautionary and adaptive management approach, and a scientific basis for management.

Based on this approach, it is revealed that Cuba’s ontology and legal configuration are more attached to the ecological aspect or process. We found that few of the identified studies develop methods to fully integrate social and ecological systems [29,48,51]. Further studies are needed to understand social–ecological systems, especially coastal marine systems, comprehensively. However, our findings are confined to studies within the literature on eco-systemic management and socio-ecosystemic management. Other results analyzed, such as work on integrated ecosystem assessment or adaptive governance models, can contribute to strengthening this approach in Cuba.

More than ten countries in the American context have provided a conceptual approximation to the approach analyzed in the legislation of different levels [50,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104]. Cuba legally legitimized this approach in 2022 in Law No. 150 of 2022, in Article 19, thus entering the range of nations that have established it as a norm. This undoubtedly leads to compliance with the defined legal rules and regulates the mechanisms for compliance.

The legal definition not only guarantees the above, but has also made possible the legal transposition into domestic law of the elements referred to in this issue in the international documents to which Cuba is a signatory, such as the Convention on Biological Diversity of 1993.

In the conceptual ontology proposed by the Cuban authors and the legal definition, three measurable characteristics of the socio-ecosystemic management structure or function are weighted. This is undoubtedly in line with the most prominent conceptual positions at the international level [1,63,91,105,106]. However, this makes it possible to structure and align, in the Cuban context, the framework of parameters that indicate the current and/or desired socio-ecological or natural quality of a given area, thus fulfilling one of the requirements of Law No. 150 of 2022, Article 19.1.b, “to implement measures according to its quantitative and qualitative durability and its renewable character”. This is in total harmony with the provisions of Article 3 of Decree Law No. 77 on Coasts: “organize activities and prioritize environmental and socioeconomic interests, considering the particularities of the ecosystems present within a region, a sector or a locality of the areas regulated in this provision, to direct the sustainable development of the territories”.

This will be possible if adaptive coastal marine governance is conceived as an approach based on the principles of integrated coastal zone management, which fosters the integrated management of ecosystem partners at the land–sea–air interface for resilience to the impacts of climate change. It aims to resolve trade-offs and provide a vision and direction for sustainability. Consequently, management is set up to operationalize this vision. And a follow-up is designed to provide feedback and synthesize the observations into a narrative of how the situation has arisen and how it might develop in the future [107].

These concepts are directly applicable to the management of coastal ecosystems in Cuba. Three reasons determine this: first, the conservation and sustainable use of the coastal zone and its protection zone, integration of the framework of the System of Natural Resources and the Environment that has been protected in Cuba since the Constitution of 2019, and the new framework law of the environment. Secondly, the specific norm, which establishes the set of mechanisms, actions, and instruments to be applied in the coastal and protection zone, Decree Law No. 77 of 2023, responds systematically to a normative coherence and hierarchy with the framework Law No. 150 of 2022. Coastal ecosystems are the object of legal protection and management by law. Thirdly, Decree Law No. 77 of 2023 itself makes an external, dynamic, and bloc referral [108,109] to the framework environmental norm when it provides: “The economic and social actions for Integrated Coastal Management respond to the general principles of environmental legislation”. This last legal expression, for legal purposes, is interpreted as meaning that the content of the referred norm is part of the referral norm [110]. Therefore, everything regulated in the framework legislation directly applies to Cuba’s coastal management.

There are several international strategic instruments for coastal zone management [10,38,89,108,111]; however, in Cuba, the integrated management program approach predominates. This was understood as an instrument that details and supports the activities to be carried out in the management area, regulating the management of its resources and the actions necessary for its conservation and sustainable use [112]. With the approval of Decree Law No. 77/2023 and its Regulation Decree No. 97 of 2023, two interesting aspects followed:

- The first is that the Program’s name is changed to Integrated Coastal Management Plan.

- Secondly, it is conceived as an administration and control tool of the provincial governments of the People’s Power to prioritize the socioeconomic interests of the institutions, social organizations, and the community to direct the sustainable development of the territories and the participation of all local actors, including civil society. This is the legal document that defines, specifies, and instrumentalizes the management in the coastal areas of Cuba currently. When carrying out a semantic analysis of the definition offered, it is observed that the legislator headed toward a conception of “precision of the details to do something”, alienating himself from what the RAE defines as a plan [113].

Assuming such a conception distances us from the conception that predominates in the world as a way of strategically implementing socio-ecological management in integrated coastal zone management. Subirat suggested that all public policies should contain concrete and individualized decisions (decisions related to the program and its implementation), which should be translated into formal acts [114]. After analyzing 30 countries, in 66% of them, the formal presentation of the document containing the policy is predominantly called “Public policies…” [115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123]. The rest, 34%, refer to it indistinctly as strategies, plans, programs, or pacts [121,124,125,126,127,128].

Secondly, the program’s concept has predominated in Cuba since 2001, from the first research on coastal management to the present. As a result of the Master’s Program in Integrated Coastal Zone Management, it is now being offered in three universities in the country: Oriente, Cienfuegos, and Havana [66,129,130].

At the international level, the structural logic of these policies is revealed [118,119,123]. They are limited to the introduction; objectives; scope; vision; physical–natural diagnosis; institutional, legal, and governance framework; socioeconomic framework; socio-ecological coastal management actions; promotion and financing actions; implementation and follow-up actions; and recommendations. In Cuba, despite observing progress in their definition and integration with socio-ecosystemic management, the aspects that will standardize these plans are lacking from the normative point of view. Therefore, it is recommended that the coastal management plans mandated by the legislation contain the name, date of approval, and validity. Coastal management problem: This should be congruent with the characteristics of intensity, scope, novelty, urgency, complexity, and concreteness; management area; key issues; general objective; specific objectives; characteristics of the ecosystem: physical–natural elements; legal–administrative elements; socioeconomic aspect; key actors; goals; actions, responsible parties; and date of compliance.

In addition to the above, Article 3 of Decree No. 97 shows that the plan must include other actions related to (a) sustainable fishing, (b) environmental sanitation of the coastal zone, (c) inter-institutional coordination, (d) environmental education, and (e) urban and tourism development.

One of the most significant challenges facing coastal zone management in Cuba with this new regulation is that the legislation states that the Integrated Coastal Management Plan is integrated into the Local Development Program. Here, we are faced with an axis and philosophy for integration, coordination, and cooperation [89]. The existence of three models that are often repeated in the reality of the public management of coastal areas is recognized: horizontal or sectoral coordination, vertical or scalar coordination, and instrumental coordination [80,89].

In this case, we are dealing with the second model of coordination, the vertical or scalar model. In other words, it is a matter of harmonizing the actions of different territorial scales of the public administration. This is not the result of chance, but it derives from the legal dynamics in the structuring of the Cuban State and the relations between its organs and agencies, which are defined firstly in the Constitution of the Republic of 2019. Also, Decree Law No. 77/2022 mandates such coordination. The above will create a legal synergy with Decree No. 33/2021, “For the Strategic Management of Territorial Development”. It will be enrolled under the fact that the latter Decree states in Article 6.2: “The municipal development strategy is an integrating instrument to guide municipal management, which has among its purposes, to achieve the satisfaction of local needs, contribute to the economic and social development of its territory and other purposes of the State”.

The coastal zone in Cuba, as manifested at the international level, is undoubtedly a complex space with highly interrelated processes among its components [50,61,131]. Addressing its governance dynamics from the conceptual framework of the DPSIR has had the objective of covering all the key components and interactions of an ecosystemic management problem. It has made it easier to identify that logic is followed by identifying the issues in the management of management programs, which is circumscribed by intensity, scope, novelty, urgency, complexity, and concreteness.

Applying the DPSIR framework, it was found that a coastal management scheme that covers the following categories is essential: description of the origin, nature, and effects of the coastal problem; specifications of the time and space and the coastal marine resources affected; key actors and institutions involved; and a set of actions, based on defined objectives, to manage the identified problem.

While the DPSIR framework has gained much recognition worldwide [67,132,133,134,135,136], there are still very few studies published in international impact journals that have adopted this approach in Cuba [48]. With this vision, a unifying platform is provided by describing and quantifying the drivers as the first step in understanding coastal and marine resource issues and their governance. Moreover, it is a framework, given the complexity of the marine system in Cuba, its uses, and its users, which provides coastal governance with the capacity to respond to unmanaged exogenous pressures as well as managed endogenous pressures [137] in a scenario relevant to climate change for Cuba. Therefore, management not only has to respond to the causes and consequences of change due to internal pressures on the system, but also responds to the consequences of external pressures [138].

5. Conclusions

This research integrates the foundations of the socio-ecosystemic approach in the dynamics of adaptive governance for coastal zones in Cuba. The proposed analysis is inspired by the principles of integrated coastal zone management, and based on this, three stages of scientific work are designed to address the object of study. The results indicate that the ecosystemic approach has a defined framework for Cuba in its research and the legislation in force, being incipient to the socio-ecosystemic approach in marine coastal governance. This is emphasized by the coastal management programs in Cuba, which defines a dynamic for marine–coastal governance. Under the logic of the DPSIR framework, it provides a platform that helps structure and facilitate the interpretation and analysis of environmental information. This last result helps us to make informed decisions in the marine coastal governance process.

This study is generally novel in its approach, and its results are essential in the Cuban context. The scientific dynamics provided can incorporate the differentiated evaluation of different management dynamics that affect reference ecosystems or others not declared in this research.

The interdisciplinary nature of this article reveals new nodes of scientific research on the role of the legal–administrative and physical–natural subsystems in the coastal zone management process and its more congruent integration challenges, for example, the evaluation of the flexibility and adaptability of legal and governance systems in projecting long-term coastal zone management, assessing how different modes of governance support different ecosystem services, and designing legal innovation strategies for the ecological sustainability of coastal zone management processes.

Coastal marine governance with an ecosystemic approach in Cuba is a dynamic process. From now on, it will face the challenge of observing the integration and normative coherence of Decree Law No. 77/2023 and its regulation with the framework legislation of the Natural Resources and Environment System, Law No. 150 of 2022, regarding the ecosystem approach as a natural resource management strategy in Cuba. Likewise, it should strengthen the integration of key actors in the coastal zone and work with the socio-ecosystemic approach to manage the principal risks and challenges that may arise. A major research challenge is the lack of mechanisms to explain why some management measures succeed or fail. Finally, in the not-too-distant future, an analysis of the regulatory impact of Decree Law No. 77/2022 and its regulations in the area under study should be carried out to offer recommendations for improvement, if any, to the relevant authorities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.Y.A.B., O.P.M., J.M.B.M. and C.B.M.; methodology, R.Y.A.B., O.P.M., J.M.B.M. and C.B.M.; software, R.Y.A.B.; validation, R.Y.A.B., O.P.M. and J.M.B.M.; formal analysis, R.Y.A.B., O.P.M., J.M.B.M. and C.B.M.; investigation, R.Y.A.B.; resources, R.Y.A.B.; data curation, R.Y.A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Y.A.B.; writing—review and editing, R.Y.A.B., O.P.M., J.M.B.M. and C.B.M.; visualization, R.Y.A.B. and C.B.M.; supervision, O.P.M. and J.M.B.M.; funding acquisition, R.Y.A.B., O.P.M., J.M.B.M. and C.B.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Partial financial support for this research was provided to Universidad del Magdalena. In addition to the Office of Management of International Funds and Projects (OGFPI) through Project PN.212.LH.012.018, named “Adaptive governance to climate change in Cuba’s coastal municipalities”, coordinated by Universidad de Oriente in Santiago de Cuba. At the same time, we are grateful to the scholarship Asociación Universitaria Iberoamericana de Postgrado (AUIP), within the framework of the Ibero-American Doctoral Training Program in Maritime and International Law, awarded since 19 October 2021.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because they are part of an ongoing PhD research at the PhD Programme in Marine Management and Conservation at the University of Cadiz, Spain. Requests for access to the datasets should be addressed to R.Y.A.B. (ralar-con@uo.edu.cu).

Acknowledgments

The excellent collaboration provided by the students of the VII Edition of the Master’s Program in Integrated Management of Coastal Zones is appreciated. This is a Program of Excellence coordinated by CEMZOC at the Universidad de Oriente. Likewise, we thank the Institute of Ecology, Fisheries and Oceanography of the Gulf of Mexico (EPOMEX), attached to the Autonomous University of Campeche, Mexico, especially to Evelia Rivera Arriaga, the academic tutor of the research carried out to obtain the International Doctorate (UCA’s own Plan 2022–2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Thematic content analysis of ICZM programs in the southeastern region of Cuba and their main results.

Objective: To identify, through thematic content analysis, the presence and development in their management dynamics of the specific criteria of the ecosystem approach proposed by the Cuban scientific doctrine and current legislation.

- Selection criteria:

- ✓

- Cognitive framework.

- ✓

- Normative framework.

- ✓

- Operational framework.

- ✓

- Recognition of the structure and function of ecosystems and their direct relationship with the goods and services they provide to local communities, society, and the ecosystem itself.

- ✓

- The contribution of appropriate scientific methodologies is oriented on the levels of biological organization, covering the essential processes, functions, and interactions between organisms and their environment, based on critical thinking.

- ✓

- Recognition that human beings, with their cultural and community diversity, are an essential component of ecosystems.

- Criteria for analysis:

Characterization of the ecosystem; valuation of ecosystem connections and its dynamic nature; the dynamics of integrated and adaptive management; identification of temporal and spatial scales; use of scientific knowledge; participation of key stakeholders; sustainability criteria; consideration of ecological integrity and biodiversity; appropriate monitoring; consideration of cumulative impacts; the presence of the precautionary approach; the role of humans in the ecosystem; and incidence of the ecosystem approach in management planning.

A. Guide for the thematic content analysis of integrated coastal zone management programs in the southeastern region of Cuba.

- I.

- General information:

- (a)

- Date of approval and validity of the program.

- (b)

- Management area.

- (c)

- Entity responsible for managing the program.

- (d)

- Entities involved in the management of the program.

- II.

- Categories and subcategories that guide the content analysis of integrated coastal zone management programs in the southeastern region of Cuba.

- II.1-.

- Data related to management planning.

- 1.

- Identification of:

- ✓

- Key subject: Yes ____ No___

- ✓

- General Objective: Yes ____ No___

- ✓

- Specific objectives: Yes ____ No___

- ✓

- Key Stakeholders: Yes ____ No___

- ✓

- Goals: Yes ____ No___

- ✓

- Actions: Yes ____ No___

- ✓

- Responsible: Yes ____ No___

- II.2-.

- Ecosystem characterization.

- ✓

- Description of the natural physical component: Yes ____ No___

- ✓

- Description of the socio-economic component: Yes ____ No___

- ✓

- Description of the legal-administrative component: Yes ____ No___

- II.3-.

- Valuation of ecosystem connections and their dynamic nature.

- ✓

- Ecological connectivity is appreciable: Yes ____ No___

- II.4-.

- Dynamics of integrated and adaptive management.

- ✓

- Multisectoral integration is appreciable: Yes ____ No___

- ✓

- Assessment of the effectiveness of management practices is appreciable: Yes ____ No___

- II.5-.

- Identification of temporal and spatial scales.

- ✓

- Time scales are clearly defined: Yes ____ No___

- ✓

- Spatial scales are clearly defined: Yes ____ No___

- II.6-.

- Use of scientific knowledge.

- ✓

- Appropriate scientific methodologies are defined for management: Yes ____ No___

- ✓

- Its role in management is appreciable: Yes ____ No___

- II.7-.

- Stakeholder participation.

- ✓

- Key stakeholders are identified: Yes ____ No___

- ✓

- Their role in the management is appreciable: Yes ____ No___

- II.8-.

- Sustainability criteria.

- ✓

- Indicators for measuring ecological sustainability are identified: Yes ____ No___

- ✓

- If yes, please indicate which ones are defined: __________________________________________________.

- II.9-.

- Consideration of ecological integrity and biodiversity.

- ✓

- Key ecological attributes and their indicators are identified: Yes ____ No___

- ✓

- Ecosystem service function is recognized: Yes ____ No___

- II.10-.

- Monitoring.

- ✓

- Monitoring actions are identified: Yes ____ No___

- II.11-.

- Consideration of cumulative impacts.

- ✓

- Actions are designed to evaluate cumulative impacts: Yes ____ No___

- ✓

- If yes, please indicate which actions are taken: __________________________________________________.

- II.12-.

- Presence of the precautionary approach.Actions are evidenced in terms of:

- ✓

- Taking precautionary measures in the face of uncertainty: Yes ____ No___

- ✓

- Shifting the burden of proof to the proponents of an activity: Yes ____ No___

- ✓

- Explore a wide range of alternatives to potentially damaging actions: Yes ____ No___

- ✓

- Increase public participation in decision making: Yes ____ No___

- II.13-.

- Human role in the ecosystem.

- ✓

- The role of human beings in the reference ecosystem is identified: Yes ____ No___

- II.14-.

- Incidence of ecosystem approach in management planning.

- ✓

- Procedural actions for decision making with an ecosystem approach are identified: Yes ____ No___

- ✓

- Institutional resources for decision making with an ecosystem approach are identified: Yes ____ No___

- ✓

- Financial and/or economic resources are identified for decision making with an ecosystem approach: Yes ____ No___.

References

- Engler, C. Beyond Rhetoric: Navigating the Conceptual Tangle Towards Effective Implementation of the Ecosystem Approach to Oceans Management; Canadian Science Publishing: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Folke, C.; Colding, J. Linking social and ecological systems: Management practices and social mechanisms for building resilience. Cambridge University Press, New York. Conserv. Ecol. 2000, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Gunderson, L.H.; Carpenter, S.R.; Ryan, P.; Lebel, L.; Folke, C.; Holling, C.S. Shooting the rapids: Navigating transitions to adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.P.; Bellwood, D.R.; Folke, C.; Steneck, R.S.; Wilson, J. New paradigms for supporting the resilience of marine ecosystems. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005, 20, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanan, A.H.; Giupponi, C. Coastal Socio-Ecological Systems Adapting to Climate Change: A Global Overview. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colding, J.; Barthel, S. Exploring the social-ecological systems discourse 20 years later. Ecol. Soc. 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thia-Eng, C. Essential Elements of Integrated Coastal Zone Management. Ocean Coast. Manag. 1993, 21, 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forst, M.F. The convergence of Integrated Coastal Zone Management and the ecosystems approach. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2009, 52, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caviedes, V.; Arenas-Granados, P.; Barragán-Muñoz, J.M. Regional public policy for Integrated Coastal Zone Management in Central America. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2020, 186, 105114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, A.M. An Ecological and economic assessment methodology for coastal ecosystem management. Environ. Manag. 2009, 44, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofelia, M.; Yunior, L.; Jorge, M.V.; Ramòn, A.B.; Alexis, P.F.; Mayelin, B.; Pedro, C.C. Manejo Integrado de Zonas Costeras y la Agenda 2030: Experiencias desde la Universidad de Oriente, Cuba. 2023. Available online: https://acortar.link/7n8gB6 (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Weiss, T.G. Governance, good governance and global governance: Conceptual and actual challenges. Third World Q. 2000, 21, 795–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyborn, C. Co-productive governance: A relational framework for adaptive governance. Glob. Environ. Change 2015, 30, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijke, J.; Brown, R.; Zevenbergen, C.; Ashley, R.; Farrelly, M.; Morison, P.; van Herk, S. Fit-for-purpose governance: A framework to make adaptive governance operational. Environ. Sci. Policy 2012, 22, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar Villanueva, L.F. The new public governance: A conceptual panorama. Perfiles Latinoam. 2024, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, A. People, oceans and scale: Governance, livelihoods and climate change adaptation in marine social-ecological systems. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 4, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, P.; Huitema, D.; Kellner, E. The Empirical Realities of Polycentric Climate Governance: Introduction to the Special Issue. Glob. Environ. Politics 2024, 24, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoker, G. Governance as theory: Five propositions. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 1998, 50, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krozer, Y.; Coenen, F.; Hanganu, J.; Lordkipanidze, M.; Sbarcea, M. Towards innovative governance of nature areas. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 441–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma-Wallace, L.; Velarde, S.J.; Wreford, A. Adaptive governance good practice: Show me the evidence! J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 222, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Our Global Neighborhood. Report of the Commission on Global Governance. Available online: https://www.gdrc.org/u-gov/global-neighbourhood/chap1.htm (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Grumbine, R.E. What Is Ecosystem Management? Conserv. Biol. 1994, 8, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, G.J.; McDonald, M.E. Application of ecological indicators. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2004, 35, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samhouri, J.F.; Lester, S.E.; Selig, E.R.; Halpern, B.S.; Fogarty, M.J.; Longo, C.; McLeod, K.L. Sea sick? Setting targets to assess ocean health and ecosystem services. Ecosphere 2012, 3, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, R.D.; Charles, A.; Stephenson, R.L. Key principles of marine ecosystem-based management. Mar. Policy 2015, 57, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, K.; Leslie, H. (Eds.) Ecosystem-Based Management for the Oceans; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Available online: https://acortar.link/wjvC4o (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Corrêa, M.R.; Xavier, L.Y.; Gonçalves, L.R.; Andrade, M.M.D.; Oliveira, M.D.; Malinconico, N.; Turra, A. Desafios para promoção da abordagem ecossistêmica à gestão de praias na América Latina e Caribe. Estud. Av. 2021, 35, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Gain, A.K.; Rogers, K.G. Sustainable coastal social-ecological systems: How do we define ‘coastal’? Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020, 27, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouffray, J.B.; Blasiak, R.; Norström, A.V.; Österblom, H.; Nyström, M. The Blue Acceleration: The Trajectory of Human Expansion into the Ocean. One Earth 2020, 2, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. The Sustainable Development Goals Report; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/files/report/2017/thesustainabledevelopmentgoalsreport2017.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Reid, W.V. Ecosystems and human well-being: Synthesis: A report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, M.; Bodin, Ö.; Guerrero, A.; Mcallister, R.; Alexander, S.; Robins, G. Theorizing the Social Structural Foundations of Adaptation and Transformation in Social-Ecological Systems. SSRN Electron. J. 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecosystem Management: Additional Actions Needed to Adequately Test a Promising Approach|U.S. GAO. Available online: https://www.gao.gov/products/rced-94-111 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Harvey, C.J.; Fluharty, D.L.; Fogarty, M.J.; Levin, P.S.; Murawski, S.A.; Schwing, F.B.; Monaco, M.E. The Origin of NOAA’s Integrated Ecosystem Assessment Program: A Retrospective and Prospective. Coast. Manag. 2021, 49, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrés, M.; Barragán, J.M.; Scherer, M. Urban centres and coastal zone definition: Which area should we manage? Land Use Policy 2018, 71, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrés García, M.; Verón, E.M.; Onetti, J.G.; Sanabria, J.G.; Granados, P.A.; Muñoz, J.M.B. Usos y actividades en el litoral andaluz. Presiones sobre los ecosistemas costero- marinos. Geografía: Cambios, retos y adaptación: Libro de actas. In Proceedings of the XVIII Congreso de la Asociación Española de Geografía, Logroño, Spain, 12–14 September 2023; pp. 503–509. [Google Scholar]

- Giupponi, C.; Ausseil, A.G.; Balbi, S.; Cian, F.; Fekete, A.; Gain, A.K.; Villa, F. Integrated modelling of social-ecological systems for climate change adaptation. Socio-Environ. Syst. Model. 2022, 3, 18161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Correa, P.C.; Kintz, J.R.C. Ecosystem-based adaptation for improving coastal planning for sea-level rise: A systematic review for mangrove coasts. Mar. Policy 2015, 51, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlüter, A.; Van Assche, K.; Hornidge, A.K.; Văidianu, N. Land-sea interactions and coastal development: An evolutionary governance perspective. Mar. Policy 2020, 112, 103801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Apa, A.; Fullerton, A.; Schwing, F.; Brady, M.M. The status of marine and coastal ecosystem-based management among the network of U.S. federal programs. Mar. Policy 2015, 60, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderies, J.M.; Janssen, M.A.; Ostrom, E. “A Framework to Analyze the Robustness of Social-ecological Systems from an Institutional Perspective”, and Society. 2004. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26267655 (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Epstein, G.; Vogt, J.M.; Mincey, S.K.; Cox, M.; Fischer, B. Missing ecology: Integrating ecological perspectives with the social-ecological system framework. Int. J. Commons 2013, 7, 432–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social-ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Change 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaceta Oficial de la República de Cuba. No. 87 Ordinaria de 13 de Septiembre de 2023, Ley No. 150, Del Sistema de Recursos Naturales y el Medio Ambiente. Available online: https://www.gacetaoficial.gob.cu/es/gaceta-oficial-no-87-ordinaria-de-2023 (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Stelzenmüller, V.; Letschert, J.; Blanz, B.; Blöcker, A.M.; Claudet, J.; Cormier, R.; Möllmann, C. Exploring the adaptive capacity of a fisheries social-ecological system to global change. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 258, 107391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz Portorreal, Y.; Beenaerts, N.; Koedam, N.; Reyes Dominguez, O.J.; Milanes, C.B.; Dahdouh-Guebas, F.; Pérez Montero, O. Perception of Mangrove Social–Ecological System Governance in Southeastern Cuba. Water 2024, 16, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaceta Oficial de la República de Cuba. No. 108 Ordinaria de 6 de Noviembre de 2023, Decreto-ley No. 77, De Costas. Available online: https://www.gacetaoficial.gob.cu/es/gaceta-oficial-no-108-ordinaria-de-2023 (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Muñoz, J.M.B. Progress of coastal management in Latin America and the Caribbean. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2020, 184, 105009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo-Valdes, J.; Pina-Amargos, F.; Figueredo-Martin, T.; Fujita, R.; Haukebo, S.; Miller, V.; Whittle, D. Managing marine recreational fisheries in Cuba for sustainability and economic development with emphasis on the tourism sector. Mar. Policy 2022, 145, 105254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarova, S.; Coyne, D.; Rodríguez, M.G.; Peteira, B.; Ciancio, A. Functional diversity of soil nematodes in relation to the impact of agriculture—A review. Diversity 2021, 13, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhartz-Muro, J.L.; Kritzer, J.P.; Gerhartz-Abraham, A.; Miller, V.; Pina-Amargós, F.; Whittle, D. An evaluation of the framework for national marine environmental policies in Cuba. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2018, 94, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karr, K.A.; Fujita, R.; Halpern, B.S.; Kappel, C.V.; Crowder, L.; Selkoe, K.A.; Rader, D. Thresholds in Caribbean coral reefs: Implications for ecosystem-based fishery management. J. Appl. Ecol. 2015, 52, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo-Valdés, J.A.; Hatcher, B.G. A new typology of benefits derived from marine protected areas. Mar. Policy 2010, 34, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.; Boyd, D.R.; Gould, R.K.; Jetzkowitz, J.; Liu, J.; Muraca, B.; Brondízio, E.S. Levers and leverage points for pathways to sustainability. People Nat. 2020, 2, 693–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, K.; Prieto, P.A.; Domínguez, A.C.; Waltner-Toews, D.; Fitzgibbon, J. Ciguatera fish poisoning in la Habana, Cuba: A study of local social-ecological resilience. Ecohealth 2008, 5, 346–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Guardia, E.; Giménez-Hurtado, E.; Defeo, O.; Angulo-Valdes, J.; Hernández-González, Z.; Espinosa–Pantoja, L.; Arias-González, J.E. Indicators of overfishing of snapper (Lutjanidae) populations on the southwest shelf of Cuba. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2018, 153, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technology Futures Analysis Methods Working Group. Technology futures analysis: Toward integration of the field and new methods. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2004, 71, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albort-Morant, G.; Henseler, J.; Leal-Millán, A.; Cepeda-Carrión, G. Mapping the field: A bibliometric analysis of green innovation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refulio-Coronado, S.; Lacasse, K.; Dalton, T.; Humphries, A.; Basu, S.; Uchida, H.; Uchida, E. Coastal and Marine Socio-Ecological Systems: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 648006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.M. “The Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries. Implementation Framework and Agenda.” FAO Fisheries Resources Division, Presented to the ICP. New York. 2006. Available online: https://www.un.org/depts/los/consultative_process/documents/7_garcia.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Rees, H.L.; Hyland, J.L.; Hylland, K.; Mercer Clarke, C.S.; Roff, J.C.; Ware, S. Environmental Indicators: Utility in Meeting Regulatory Needs. An Overview. 2008. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/icesjms/article/65/8/1381/714382 (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Atienza, M. Las Razones del Derecho: Teorías de la Argumentación Jurídica; Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas, Serie Doctrina Jurídica, Núm. 134, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Ciudad de México, México, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Abela, J.A. Las Técnicas de Análisis de Contenido: Una Revisión Actualizada. Fundación Centro de Estudios Andaluces: Sevilla, Spain, 2002; 34p. [Google Scholar]

- Maestría en Manejo Integrado de Zonas Costeras—Centro de Estudios Multidisciplinarios de Zonas Costeras. Available online: https://blogs.uo.edu.cu/maestriacemzoc/ (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Marcos, M.; Francisco, C. The DPSIR framework applied to the integrated management of coastal areas. In Perspectives on Integrated Coastal Zone Management in South America; IST Press: Lisbon, Portugal, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agardy, T.S. Taking Steps Toward Marine and Coastal Ecosystem-Based Management: An Introductory Guide; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Panorama Ambiental Cuba 2023. Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas e Información. República de Cuba, Dirección de Estadísticas Básicas, Edición Noviembre 2023. Available online: http://onei.gob.cu/ambiental (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Anuario Estadístico de Cuba 2023. Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas e Información. República de Cuba, Dirección de estadísticas básicas, Edición 2024. Available online: http://onei.gob.cu/cuba (accessed on 14 November 2024).