Climate Change Management and Firm Value: Insights from Southeast Asia Markets (A Survey of Public Companies in Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand for the 2022–2023 Period)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Stakeholder Theory

2.2. Agency Theory

2.3. Legitimacy Theory

2.4. Climate Change and Company Policy

2.5. Firm Value

2.6. Hypothesis Development

3. Methods

- For descriptive analysis of the data, statistical measures, such as means, standard deviations, and maximum and minimum values, were computed. Additional descriptive examinations were conducted by comparing averages across three categories: (a) yearly, to observe annual fluctuations in variable components; (b) by country, to assess potentially significant disparities in climate change management policy between nations; and (c) by industry, to evaluate potentially significant variations in the same climate change management policy aspects across different sectors. The industry categorization employed follows the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS), a system that groups companies based on their primary business activities. The GICS comprises 11 sectors: (i) energy, (ii) materials, (iii) industrial, (iv) consumer discretionary, (v) consumer staples, (vi) health care, (vii) financials, (viii) information technology (IT), (ix) communication services, (x) utilities, and (xi) real estate. More detailed data can be found in Appendix A below.

- To determine whether the observed differences between years were statistically significant, this study utilized the paired sample t-test for year-on-year comparisons, while the ANOVA test was applied to examine differences among countries and industries.

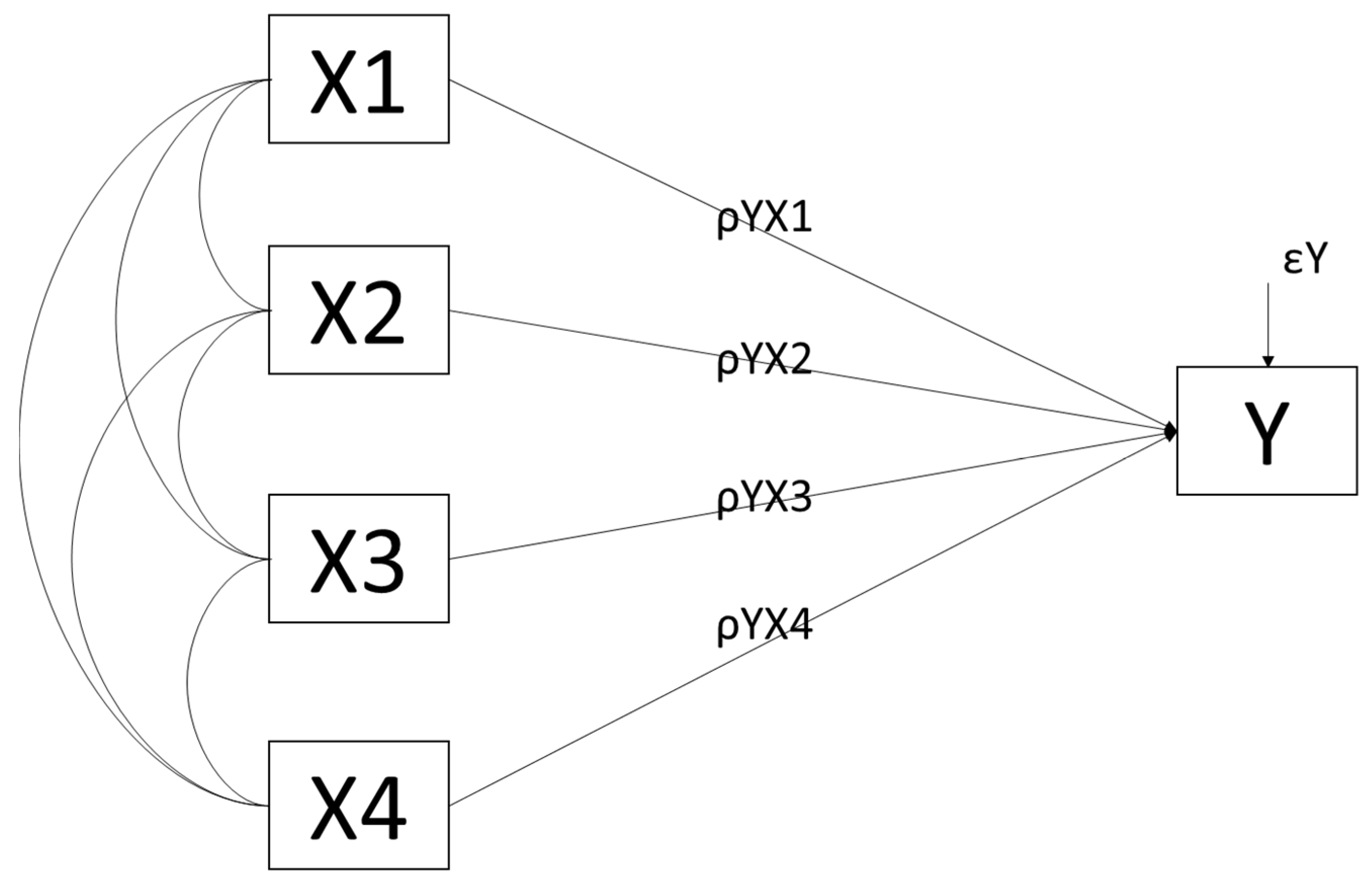

- A path analysis tool was used to test this hypothesis. Path analysis was used because the control variables in the model were theoretically related to each other. To test this hypothesis, path analysis was conducted to assess the direct effect of climate policy management (X1) on firm value (Y) while controlling for firm size (X2), profitability (X3), and cost of debt (X4). Firm size is related to profitability because it may result from the use of firm assets. Large company assets can generate high profits. Company assets are also a significant guarantee of debt; therefore, company size is related to the cost of debt. Company profitability can also reduce the cost of debt because of the high level of investor confidence in companies with high profitability, which indicates low financial risk. Path analysis was performed using the ordinary least squares (OLS) approach, so classical assumption testing was required in the form of normality, multicollinearity, heteroscedasticity, and autocorrelation tests to ensure that the model would be sufficiently good for testing. The path diagram for this study is presented in Figure 1. The path equation is as follows:

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Results

4.1.1. General Descriptives

4.1.2. Climate Change Management Policy Descriptives

4.1.3. ANOVA

4.1.4. Path Analysis

4.1.5. Robustness Test

4.2. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Term |

| CSR | Corporate social responsibility |

| GSCM | Green supply chain management |

| OLS | Ordinary least squares |

| PBV | Price-to-book value |

Appendix A. Country and Industry Distribution of Sample Companies

| Country/Sector | Number of Companies | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Per Country | ||

| Indonesia | 61 | 11.5% |

| Malaysia | 304 | 57.3% |

| Thailand | 166 | 31.3% |

| Per Industry Sector | ||

| Financials | 59 | 11.1% |

| Industrials | 100 | 18.8% |

| Real Estate | 50 | 9.4% |

| Communication Services | 32 | 6.0% |

| Consumer Staples | 69 | 13.0% |

| Information Technology | 39 | 7.3% |

| Consumer Discretionary | 55 | 10.4% |

| Utilities | 28 | 5.3% |

| Materials | 51 | 9.6% |

| Energy | 29 | 5.5% |

| Health Care | 19 | 3.6% |

References

- Hsueh, L. Opening up the firm: What explains participation and effort in voluntary carbon disclosure by global businesses? An analysis of internal firm factors and dynamics. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1302–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpuokwe, C.; Eneh, N.; Bakare, S.; Adeniyi, A. Legislative Responses to Climate Change: A Global Review of Policies and Their Effectiveness. Int. J. Appl. Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 6, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digitemie, W.; Ekemezie, I. Assessing the role of carbon pricing in global climate change mitigation strategies. Magna Sci. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 10, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, A.; Wong, C.Y.; Hashim, F.; Ooi, S.K. Business Strategy for Climate Change: An ASEAN Perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 23, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todaro, N.M.; Testa, F.; Daddi, T.; Iraldo, F. The influence of managers’ awareness of climate change, perceived climate risk exposure and risk tolerance on the adoption of corporate responses to climate change. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 30, 1232–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damert, M.; Feng, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Baumgartner, R.J. Motivating low-carbon initiatives among suppliers: The role of risk and opportunity perception. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 136, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosma, S.; Principale, S.; Venturelli, A. Sustainable governance and climate-change disclosure in European banking: The role of the corporate social responsibility committee. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2022, 22, 1345–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, A.; Gladstone, J.; Turner, W.R.; Hole, D.G. The private sector’s climate change risk and adaptation blind spots. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 9, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, S.; Fruitiere, C.; Irwin, W.; Rauis, B.; Sullivan, R.; Garcia-Manas, C. An assessment of climate action by high-carbon global corporations. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olekanma, O.; Rodrigo, L.S.; Gahir, B.; Adu, D.A. Small- and medium-sized enterprises’ carbon footprint reduction initiatives as a catalyst for green jobs: A systematic review and comprehensive business strategy agenda. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 6911–6939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Amar, W.; Mcilkenny, P.; Chang, M. Board Gender Diversity and Corporate Response to Sustainability Initiatives: Evidence from the Carbon Disclosure Project. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 142, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pricopoaia, O.; Mihai, I.O.; Lupașc, A. Implications of Innovative Strategies for Sustainable Entrepreneurship—Solutions to Combat Climate Change. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhayawansa, S.; Adams, C. Towards a conceptual framework for non-financial reporting inclusive of pandemic and climate risk reporting. Meditari Account. Res. 2021, 30, 710–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubaker, N. The Role of Environmental Accounting in Mitigating Environmental Pollution Risk and its Disclosure. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. IJISRT 2024, 9, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, B.; Unerman, J. Shifting the focus of sustainability accounting from impacts to risks and dependencies: Researching the transformative potential of TCFD reporting. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2020, 33, 1113–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Jahanshahi, A.A.; Chakraborty, S. Unlocking the link between low emission supply chains, blockchain adoption, and financial success: The payoff of socially responsible practices in supply chains. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2024, 7, e341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albitar, K.; Al-Shaer, H.; Liu, Y.S. Corporate commitment to climate change: The effect of eco-innovation and climate governance. Res. Policy 2022, 52, 104697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.H.; Wang, C.; Kerstein, J.; Wu, F. Firm climate risk, risk management, and bank loan financing. Strateg. Manag. J. 2022, 43, 2849–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Perera, L.; Abhayawansa, S.; Jubb, C. Regulatory impact on voluntary climate change–related reporting by Australian government-owned corporations. Financ. Account. Manag. 2017, 33, 264–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahramanova, G.; Kutlu Furtuna, Ö. Corporate climate change disclosures and capital structure strategies: Evidence from Türkiye. J. Cap. Mark. Stud. 2023, 7, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.; Holt, D. Do green supply chains lead to competitiveness and economic performance? Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2005, 25, 898–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P. Greening the supply chain: A new initiative in South East Asia. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2002, 22, 632–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, J.; Najah, M.M. Institutional investor influence on global climate change disclosure practices. Aust. J. Manag. 2012, 37, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, D.M. Demystifying the link between institutional theory and stakeholder theory in sustainability reporting. Econ. Manag. Sustain. 2018, 3, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brulhart, F.; Gherra, S.; Quelin, B.V. Do Stakeholder Orientation and Environmental Proactivity Impact Firm Profitability? J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 158, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprengel, D.C.; Busch, T. Stakeholder engagement and environmental strategy—The case of climate change. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 20, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A.; Pinkse, J. Towards strategic stakeholder management? Integrating perspectives on sustainability challenges such as corporate responses to climate change. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2007, 7, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Dow, S. Corporate governance and business strategies for climate change and environmental mitigation. Eur. J. Financ. 2012, 18, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, A.; Zulkafli, A.H.; Periasamy, V. Determinants of Climate Change Disclosure by Developed and Emerging Countries in Asia Pacific. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 22, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, F.; Guo, J.; Srivastava, M.; Sun, J. Green corporate image: Assessing the effects of climate change management practices on corporate reputation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 31, 1786–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyglidopoulos, S.C. The Issue Life-Cycle: Implications for Reputation for Social Performance and Organizational Legitimacy. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2003, 6, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana-García, C.; Benavides-Chicón, C.G.; Marchante-Lara, M. Towards sustainable development: Environmental innovation, cleaner production performance, and reputation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1330–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Srivastava, J. CSR, monitoring cost and firm performance during COVID-19: Balancing organizational legitimacy and agency cost. Account. Res. J. 2023, 36, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagh, T.; Khan, M.A.; Bouri, E. Climate change sentiment, ESG practices and firm value: International insights. China Financ. Rev. Int. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendtorff, J.D. The Concept of Business Legitimacy: Corporate Social Responsibility. In Corporate Citizenship, Corporate Governance as Essential Elements of Ethical Business Legitimacy; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannarakis, G.; Zafeiriou, E.; Sariannidis, N. The Impact of Carbon Performance on Climate Change Disclosure. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 1078–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daradkeh, H.; Bose, S.; Shams, S.; Gunasekarage, A. Does managerial ability matter for corporate climate change disclosures? Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2022, 31, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C.; Toffel, M.W.; Viswanathan, K. Shareholder activism and firms’ voluntary disclosure of climate change risks. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 42, 1850–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzato, F.; Fiandrino, S.; Devalle, A.; Tonelli, A. Analysing SDG disclosure and its impact on integrated thinking and reporting. Meditari Account. Res. 2023, 32, 803–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principale, S.; Pizzi, S. The Determinants of TCFD Reporting: A Focus on the Italian Context. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yan, F.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y. Evaluating provincial carbon emission characteristics under China’s carbon peaking and carbon neutrality goals. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 156, 111146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Majid, J.; Che Adam, N.; Ab Rahim, N.; Razak, R. CEO power, regulatory pressures, and carbon emissions: An emerging market perspective. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2276555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliana, Y.; Wedari, L.K. Carbon Performance, Green Strategy, Financial Performance Effect on Carbon Emissions Disclosure: Evidence from High Polluting Industry in Indonesia. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2023, 18, 1581–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohar, R.; Uche, E.; Kalra, A.; Chang, B.H.; Uddin, M.A. Nexus between energy consumption, climate risk development finance and GHG emissions. Int. J. Financ. Eng. 2023, 10, 2350025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Sánchez, M.; Martín-Ortega, J.L. Greenhouse Gas Emissions Growth in Europe: A Comparative Analysis of Determinants. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minhas, A.S.; Maqsood, N.; Rehman, A.U.; Shahid, T.A. Investment Performance in Green Finance: Assessing the Impact of Environmental Social and Governance Integration. IRASD J. Econ. 2024, 6, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbano, V.C.; Delmas, M.A.; Cobo, M.J. The Past and Future of Corporate Sustainability Research. Organ. Environ. 2023, 37, 133–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, N.A.; Pratama, A. Quality of financial disclosures related to environmental, social, and governance matters, and firm characteristics and firm value: A comparative study across four ASEAN countries. Int. J. Manag. Sustain. 2023, 12, 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohy-Ud-Din, K.; Du, A.M.; Shahbaz, M. Corporate social responsibility and climate change mitigation: Discovering the interaction role of green audit and sustainability committee. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 32, 1198–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida Barbosa Franco, J.; Bezerra, B.S.; Franco, A., Jr.; Battistelle, R.A.G. Dynamic Capabilities: Unveiling Key Resources for Environmental Sustainability and Economic Sustainability, and Corporate Social Responsibility towards Sustainable Development Goals. Resources 2024, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbannan, M.A. Accounting and stock market effects of international accounting standards adoption in an emerging economy. Rev. Quant. Financ. Account. 2010, 36, 207–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; Maffett, M.; Lins, K.V. Transparency, Liquidity, and Valuation: International Evidence on When Transparency Matters Most. J. Account. Res. 2012, 50, 729–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestrelli, R.; Fronzetti Colladon, A.; Pisello, A.L. When attention to climate change matters: The impact of climate risk disclosure on firm market value. Energy Policy 2023, 185, 113938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.; Nadeem, M.; Bhabra, G.S.; Pandey, R. Do capital markets reward corporate climate change actions? Evidence from the cost of debt. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 32, 3417–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, C.; Fraas, J.W. Coming Clean: The Impact of Environmental Performance and Visibility on Corporate Climate Change Disclosure. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 100, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Tian, J. The Mediating Role of Responsible Innovation in the Relationship between Stakeholder Pressure and Corporate Sustainability Performance in Times of Crisis: Evidence from Selected Regions in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Jiang, P.; Elamer, A.A.; Owusu, A. Environmental performance and corporate innovation in China: The moderating impact of firm ownership. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 184, 121990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Zamora, E.; González-Benito, Ó.; Muñoz-Gallego, P.A. Organizational and environmental factors as moderators of the relationship between multidimensional innovation and performance. Innovation 2013, 15, 224–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asni, N.; Agustia, D. The mediating role of financial performance in the relationship between green innovation and firm value: Evidence from ASEAN countries. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 25, 1328–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hiyari, A.; Ismail, A.I.; Kolsi, M.C.; Kehinde, O.H. Environmental, social and governance performance (ESG) and firm investment efficiency in emerging markets: The interaction effect of board cultural diversity. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2022, 23, 650–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadori, N.; Kaymak, T.; Seraj, M. Environmental, social, and governance factors in emerging markets: The impact on firm performance. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2021, 4, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treepongkaruna, S.; Suttipun, M. The impact of environmental, social and governance (ESG) reporting on corporate profitability: Evidence from Thailand. J. Financ. Report. Account. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, A.S.; Elmarzouky, M. Beyond Compliance: How ESG Reporting Influences the Cost of Capital in UK Firms. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2024, 17, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Gao, Y.; Hong, D. Sustainable Innovation and Economic Resilience: Deciphering ESG Ratings’ Role in Lowering Debt Financing Costs. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 16, 4309–4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, I.; Chaudhuri, T.D. FEB-Stacking and FEB-DNN Models for Stock Trend Prediction: A Performance Analysis for Pre and Post COVID-19 Periods. Decis. Mak. Appl. Manag. Eng. 2021, 4, 51–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defung, F.; Yudaruddin, R.; Hadjaat, M. COVID-19 pandemic and firm performance in leisure, arts, and hospitality industries: International evidence. Invest. Manag. Financ. Innov. 2023, 20, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Pei, J. Do green financial and non-financial policies achieve the carbon neutrality target? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 97965–97976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Manoharan, S. Effects of Corporate Greenwashing on Society; Corporate Greenwashing and Sustainability. Shanlax Int. J. Arts Sci. Humanit. 2024, 11, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratama, A.; Yusoff, H.; Yadiati, W.; Jaenudin, E. Sustainability-related corporate governance and greenwashing practices: Preliminary evidence from southeast Asian companies. Meditari Account. Res. 2025. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huiskamp, U.; Ten Brinke, B.; Kramer, G.J. The climate resilience cycle: Using scenario analysis to inform climate-resilient business strategies. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 1763–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, N.I.; Yang, B.; Lv, Y.; Enamul, M.M.; Huq, E.; Kamruzzaman, M.M. Climate Change Adaptation and Resilience through Big Data. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2020, 11, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, S.; Gradwell, P.; Bowen, A.; Dixon, C. ‘Climate value at risk’ of global financial assets. Nat. Clim. Change 2016, 6, 676–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Ren, X. The Response of Corporate Innovation to Climate Policy Uncertainty: Evidence from China. J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manag. 2023, 25, 2350008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingler, J.A.; Kraus, M.; Leippold, M.; Webersinke, N. Cheap talk and cherry-picking: What ClimateBert has to say on corporate climate risk disclosures. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 47, 102776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Kumar, R.; Kumari, R. The state of corporate sustainability reporting in India: Evidence from environmentally sensitive industries. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2021, 126, 513–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, V.; Kaur, A. Does Socially Responsible Investing Pay in Developing Countries? A Comparative Study Across Select Developed and Developing Markets. FIIB Bus. Rev. 2021, 11, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodhanwala, S.; Bodhanwala, R. Relationship between sustainable and responsible investing and returns: A global evidence. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 16, 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renukappa, S.; Akintoye, A.; Goulding, J.; Egbu, C. Carbon emission reduction strategies in the UK industrial sectors: An empirical study. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2013, 5, 304–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenci, S.; Tang, S. Addressing companies’ low-carbon transition challenges requires diversified investments in environmental initiatives. Clim. Change 2024, 177, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyoni, V.; Broberg Piller, W.; Vigren, O. Sustainability action in the real estate sector—An organizational and institutional perspective. Clean. Prod. Lett. 2023, 5, 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nweje, U.; Taiwo, M. Supply chain management: Balancing efficiency and environmental responsibility. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2025, 25, 1547–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhania, M.; Saini, N. Institutional framework of ESG disclosures: Comparative analysis of developed and developing countries. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2021, 13, 516–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ab Aziz, N.H.; Osman, M.N.H.; Azmi, N.A.; Alshdaifat, S.M.; Abdul Latiff, A.R. ESG Disclosure and Firm Performance: Evidence after the Revision of Malaysian Code of Corporate Governance. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2023, 13, 2919–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, I. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Practice and Firm Performance: An International Evidence. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2022, 23, 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaludin, K.; Ibrahim, I.; Faizal, O.; Sundarasen, S. ESG in the boardroom: Evidence from the Malaysian market. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2022, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.C. Impact of green investments, green economic growth and renewable energy consumption on environmental, social, and governance practices to achieve the sustainable development goals: A sectoral analysis in the ASEAN economies. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2024, 16, 18479790241231725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuadah, L.L.; Arisman, A.; Andriana, I.; Mukhtaruddin, M. The Ownership Structure, and the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure, Firm Value and Firm Performance: The Audit Committee as Moderating Variable. Economies 2022, 10, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja Ahmad, R.A.; Azmi, N.A.; Samsuddin, M.E.; Abdullah, N. Is Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Disclosure Value Enhancing? Evidence from Top 100 Companies. Asia-Pac. Manag. Account. J. 2023, 18, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurunnabi, M. Who cares about climate change reporting in developing countries? The market response to, and corporate accountability for, climate change in Bangladesh. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2015, 18, 157–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miras-Rodríguez, M.D.M.; Martínez-Martínez, D.; Escobar-Pérez, B. Which Corporate Governance Mechanisms Drive CSR Disclosure Practices in Emerging Countries? Sustainability 2018, 11, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D. Social Reporting and New Governance Regulation: The Prospects of Achieving Corporate Accountability Through Transparency. Bus. Ethics Q. 2007, 17, 453–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, S.; Sullivan, R. Public policy, institutional investors and climate change: A UK case-study. Clim. Change 2008, 89, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu, D.A.; Roni, N.N. Bank climate change initiatives, ownership structures, and corporate governance mechanisms: Evidence from emerging economies. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 33, 3039–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Tang, Q.; Lan, Y. Corporate Incentives to Disclose Carbon Information: Evidence from the CDP Global 500 Report. J. Int. Financ. Manag. Account. 2012, 23, 93–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Luo, L.; Shamsuddin, A.; Tang, Q. The Value Relevance of Corporate Investment in Carbon Abatement: The Influence of National Climate Policy. Eur. Account. Rev. 2021, 31, 1233–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucel, M.; Yucel, S. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Dynamics in the Energy Sector: Strategic Approaches for Sustainable Development. Energies 2024, 17, 6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paridhi, P.; Ritika, R. Impact of ESG Disclosures on Corporate Financial Performance: An Industry-Specific Analysis of Indian Firms. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2025, 8, e70055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Tsang, A.; Zhu, N.Z.; Wang, K.T. Corporate Governance Reforms and Cross-Listings: International Evidence. Contemp. Account. Res. 2021, 39, 537–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Shams, S.; Lim, E.K.; Minnick, K. Do foreign institutional investors influence corporate climate change disclosure quality? International evidence. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2023, 32, 322–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, S. What comes next: Responding to recommendations from the task force on climate-related financial disclosures (TCFD). APPEA J. 2018, 58, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.K.; Khan, I. Regulatory influence, board characteristics and climate change disclosures: Evidence from environmentally sensitive firms in developing economy context. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2024, 24, 1442–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duparc-Portier, G.; Figus, G. How should governments respond to energy price crises? A horse-race between fiscal policies. Energy Econ. 2024, 130, 107284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempa, K.; Schenker, O.; Moslener, U. The cost of debt of renewable and non-renewable energy firms. Nat. Energy 2021, 6, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendratama, T.D.; Huang, Y.-C. Corporate social responsibility, firm value and life cycle: Evidence from Southeast Asian countries. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2021, 22, 577–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukmadilaga, C.; Lestari, T.U.; Yudianto, I.; Winarningsih, S.; Ghani, E.K. Does Green Accounting Affect Firm Value? Evidence from ASEAN Countries. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2023, 13, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beirne, J.; Renzhi, N.; Volz, U. Bracing for the Typhoon: Climate change and sovereign risk in Southeast Asia. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, B.; Giordano-Spring, S. Climate Reporting Related to the TCFD Framework: An Exploration of the Air Transport Sector. Soc. Environ. Account. J. 2021, 42, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewumi, A.S.; Dangana, Z.; Opoku, A. Sustainability assessment frameworks for delivering Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) targets: A case of Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM) UK New Construction. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 3779–3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, M.A.A.; Issa, A. A roadmap for triggering the convergence of global ESG disclosure standards: Lessons from the IFRS foundation and stakeholder engagement. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2023, 23, 1648–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Climate Change Policy Management (X1) | Calculated based on the presence of 13 elements presented according to the Refinitiv Eikon Database as follows:

|

| Company Size (X2) | Company size was calculated based on the natural logarithm (Ln) of the total asset value. The company size value was taken from the Total Asset—Reported from the Refinitiv Eikon Database. |

| Profitability (X3) | Profitability was calculated from the return-on-asset (ROA) value which is the division between the value of net income divided by the value of total assets. The net income value was taken from Refinitiv Eikon, in the Net Income After Taxes—Reported classification, and the asset value was taken from the Total Asset—Reported classification. |

| Cost of Debt (X4) | The cost of debt was calculated from the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) debt taken from Refinitiv Eikon. Refinitiv determines the cost of debt using the following: Interest expense/average total debt → effective interest rate approach; Yield-to-maturity (YTM) of corporate bonds (if available); Credit spreads and risk-free rate adjustments (based on a company’s credit rating); Industry benchmarks for companies with similar debt structures. The WACC Debt equation used by Refinitiv Eikon is as follows: WACC = weighted average cost of capital; E = market value of equity; D = market value of debt; V = total capital = E + D; Re = cost of equity; Rd = cost of debt; Tc = corporate tax rate. |

| Price-to-Book Value (Y) | The PBV equation used by Refinitiv Eikon is as follows: PBV = price-to-book value ratio; P = market price per share; BVPS = book value per share = total shareholders’ equity/total outstanding shares. |

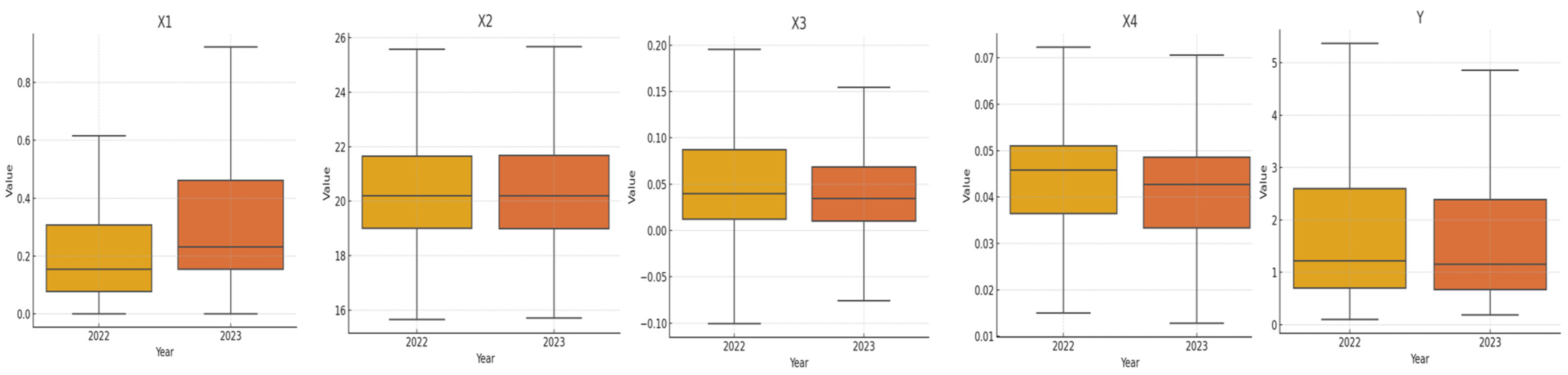

| Variable | X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | Y | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2022 | 2023 | 2022 | 2023 | 2022 | 2023 | 2022 | 2023 | 2022 | 2023 |

| Mean | 0.219 | 0.285 | 20.390 | 20.409 | 0.075 | 0.039 | 0.043 | 0.043 | 2.374 | 2.148 |

| Std. Dev | 0.199 | 0.212 | 1.903 | 1.908 | 0.593 | 0.116 | 0.014 | 0.019 | 4.545 | 4.128 |

| Min | 0.000 | 0.000 | 14.770 | 15.710 | −0.540 | −1.670 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.100 | 0.180 |

| Max | 0.850 | 0.920 | 26.100 | 26.130 | 13.570 | 0.890 | 0.090 | 0.190 | 59.830 | 63.100 |

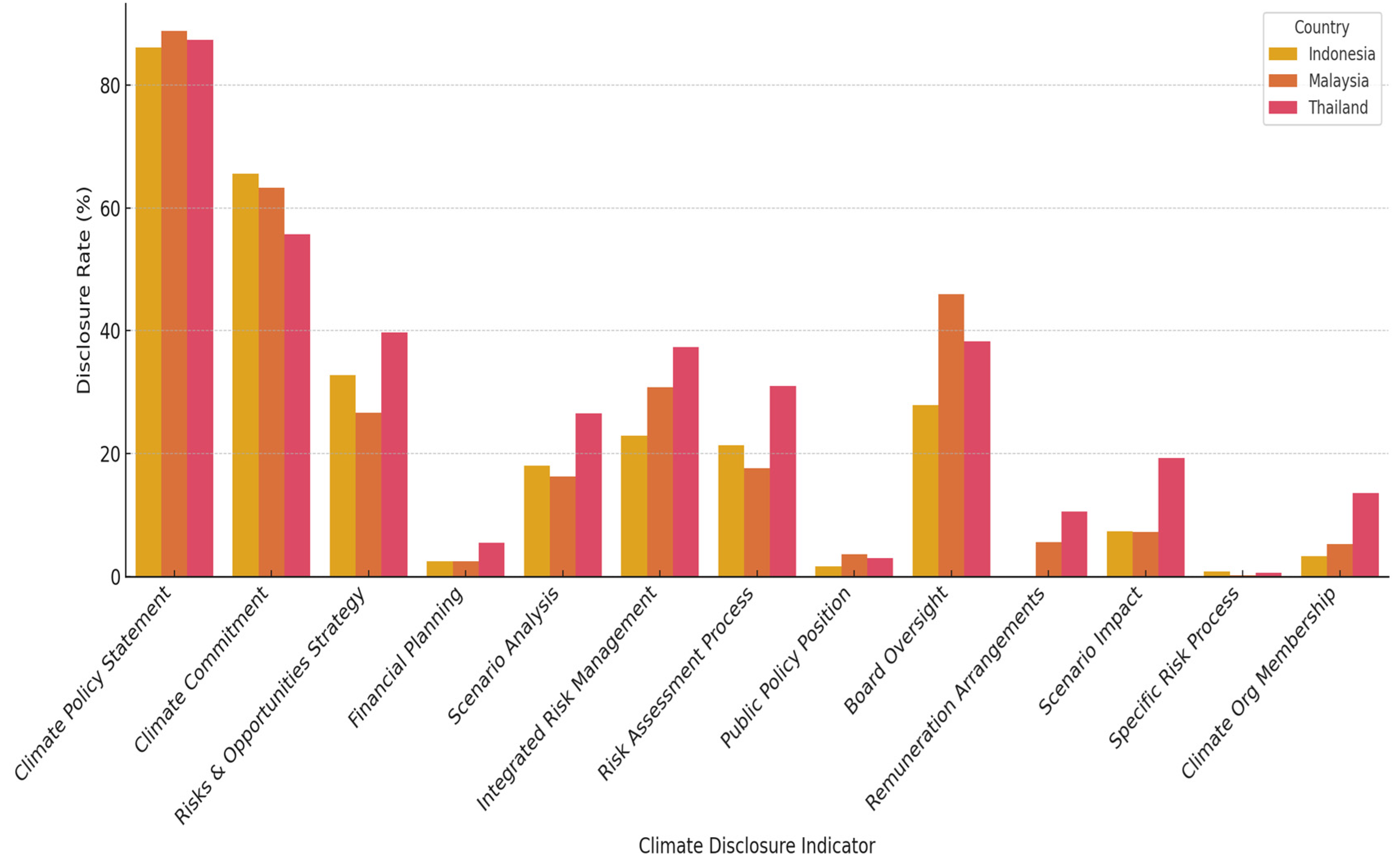

| Variable/Explanation | Year | Indonesia | Malaysia | Thailand | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of Companies That Disclosed | |||||

| Climate Policy Statement | 2023 | 54 | 281 | 162 | 497 |

| 88.52% | 92.43% | 97.59% | 93.60% | ||

| 2022 | 51 | 259 | 128 | 438 | |

| 83.61% | 85.20% | 77.11% | 82.49% | ||

| Climate Commitment | 2023 | 44 | 209 | 102 | 355 |

| 72.13% | 68.75% | 61.45% | 66.85% | ||

| 2022 | 36 | 176 | 83 | 295 | |

| 59.02% | 57.89% | 50.00% | 55.56% | ||

| Climate Change Risks and Opportunities Strategy | 2023 | 21 | 91 | 81 | 193 |

| 34.43% | 29.93% | 48.80% | 36.35% | ||

| 2022 | 19 | 71 | 51 | 141 | |

| 31.15% | 23.36% | 30.72% | 26.55% | ||

| Climate Change Risks and Opportunities in Financial Planning | 2023 | 2 | 9 | 11 | 22 |

| 3.28% | 2.96% | 6.63% | 4.14% | ||

| 2022 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 14 | |

| 1.64% | 1.97% | 4.22% | 2.64% | ||

| Climate-Related Scenario Analysis | 2023 | 16 | 57 | 47 | 120 |

| 26.23% | 18.75% | 28.31% | 22.60% | ||

| 2022 | 6 | 42 | 41 | 89 | |

| 9.84% | 13.82% | 24.70% | 16.76% | ||

| Climate-Related Risks Integrated into Risk Management | 2023 | 19 | 108 | 73 | 200 |

| 31.15% | 35.53% | 43.98% | 37.66% | ||

| 2022 | 9 | 79 | 51 | 139 | |

| 14.75% | 25.99% | 30.72% | 26.18% | ||

| Climate-Related Risks Assessment Process | 2023 | 16 | 64 | 61 | 141 |

| 26.23% | 21.05% | 36.75% | 26.55% | ||

| 2022 | 10 | 43 | 42 | 95 | |

| 16.39% | 14.14% | 25.30% | 17.89% | ||

| Company Position Climate-Related Public Policy | 2023 | 1 | 12 | 6 | 19 |

| 1.64% | 3.95% | 3.61% | 3.58% | ||

| 2022 | 1 | 10 | 4 | 15 | |

| 1.64% | 3.29% | 2.41% | 2.82% | ||

| Board Oversight of Climate Change Risks | 2023 | 20 | 155 | 80 | 255 |

| 32.79% | 50.99% | 48.19% | 48.02% | ||

| 2022 | 14 | 124 | 47 | 185 | |

| 22.95% | 40.79% | 28.31% | 34.84% | ||

| Remuneration Arrangements Incorporate Climate Change | 2023 | 0 | 20 | 23 | 43 |

| 0.00% | 6.58% | 13.86% | 8.10% | ||

| 2022 | 0 | 14 | 12 | 26 | |

| 0.00% | 4.61% | 7.23% | 4.90% | ||

| Business Impact of Climate Scenario Analysis | 2023 | 7 | 25 | 35 | 67 |

| 11.48% | 8.22% | 21.08% | 12.62% | ||

| 2022 | 2 | 19 | 29 | 50 | |

| 3.28% | 6.25% | 17.47% | 9.42% | ||

| Specific Climate-Related Risk Management Process | 2023 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 1.64% | 0.33% | 0.60% | 0.56% | ||

| 2022 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.60% | 0.19% | ||

| Membership in any Organizations Dedicated to Climate-Related Issues. | 2023 | 3 | 18 | 32 | 53 |

| 4.92% | 5.92% | 19.28% | 9.98% | ||

| 2022 | 1 | 14 | 13 | 28 | |

| 1.64% | 4.61% | 7.83% | 5.27% | ||

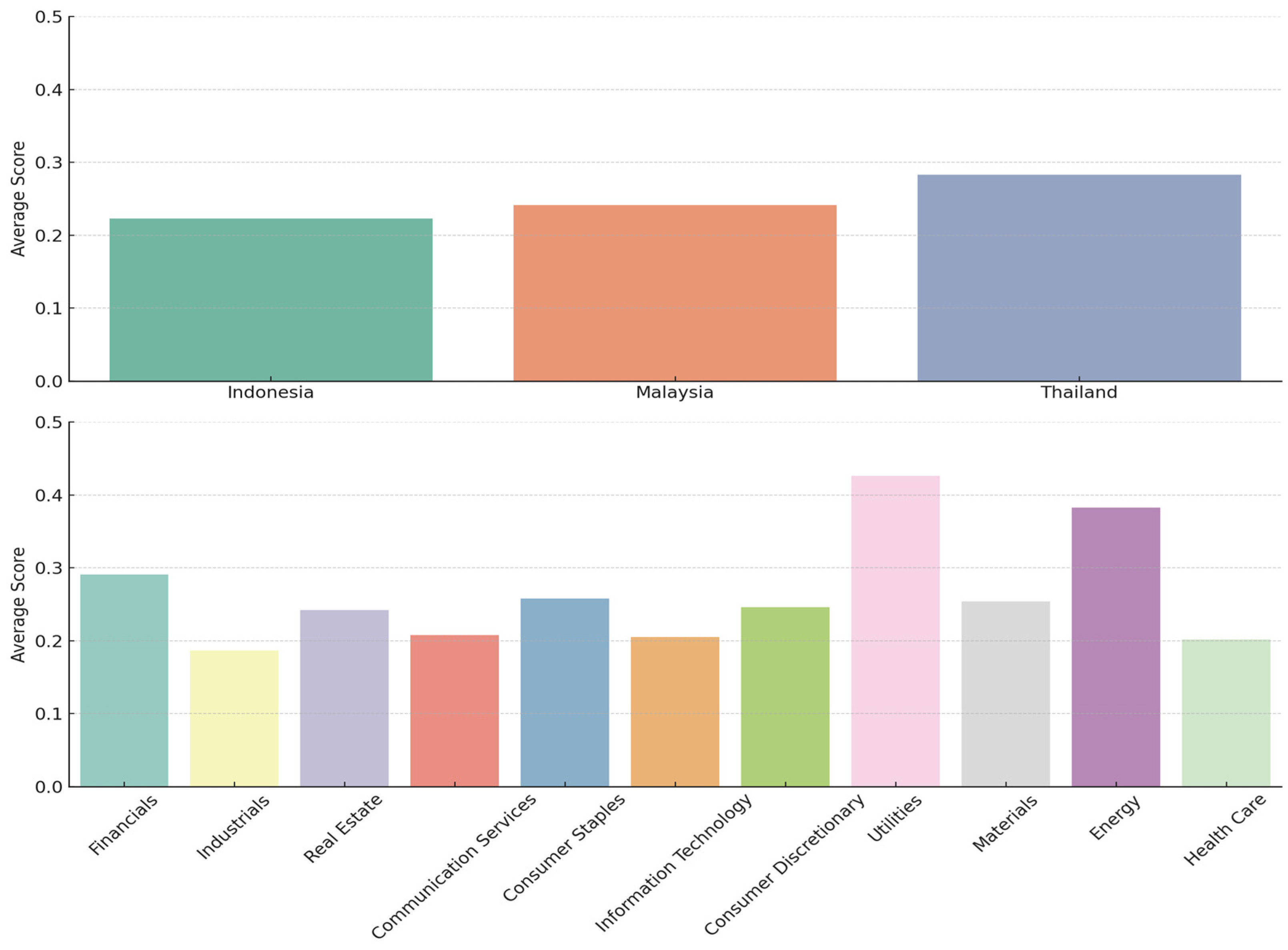

| Variable/Explanation | 2-Year Average Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | Y | |

| Per Country | |||||

| Indonesia | 0.223 | 21.668 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 2.672 |

| Malaysia | 0.241 | 19.812 | 0.062 | 0.062 | 2.223 |

| Thailand | 0.283 | 21.009 | 0.054 | 0.054 | 2.180 |

| Overall | 0.252 | 20.399 | 0.057 | 0.057 | 2.261 |

| ANOVA test-score | 5.850 | 84.519 | 0.198 | 10.836 | 0.626 |

| Sig | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.821 | 0.000 | 0.535 |

| Per Industry | |||||

| Financials | 0.291 | 22.465 | 0.018 | 0.044 | 2.625 |

| Industrials | 0.187 | 19.552 | 0.099 | 0.045 | 2.085 |

| Real Estate | 0.242 | 20.757 | 0.028 | 0.045 | 0.873 |

| Communication Services | 0.208 | 20.981 | 0.052 | 0.049 | 2.720 |

| Consumer Staples | 0.258 | 20.051 | 0.071 | 0.039 | 3.342 |

| Information Technology | 0.205 | 18.986 | 0.054 | 0.042 | 3.016 |

| Consumer Discretionary | 0.246 | 19.875 | 0.043 | 0.041 | 2.411 |

| Utilities | 0.426 | 21.549 | 0.037 | 0.050 | 1.467 |

| Materials | 0.254 | 20.073 | 0.043 | 0.042 | 1.648 |

| Energy | 0.383 | 21.386 | 0.069 | 0.044 | 1.650 |

| Health Care | 0.202 | 19.883 | 0.081 | 0.039 | 2.783 |

| Overall | 0.252 | 20.399 | 0.057 | 0.043 | 2.261 |

| ANOVA Test Score | 10.312 | 38.697 | 0.401 | 3.598 | 2.926 |

| Sig | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.947 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| Classical Assumption Test | Score | Criteria for Good Fit | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normality test (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test) | 0.000 | sig > 0.05 | Not passed |

| Multicollinearity test (variance inflation factor) | 1.016–1.422 | VIF < 10 | Passed |

| Heteroscedasticity test (White test) | 0.691 | sig > 0.05 | Passed |

| Autocorrelation test (serial correlation LM test) | 0.808 | sig > 0.05 | Passed |

| Variable | Path Coefficient | t-Statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | 0.11 | 3.542 | 0.000 |

| X2 | −0.15 | −4.417 | 0.000 |

| X3 | 0.11 | 3.151 | 0.002 |

| X4 | −0.06 | −2.451 | 0.014 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.030 | ||

| F-statistic | 9.329 | ||

| Prob(F-statistic) | 0.000 | ||

| Subsample | X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | Adj R2 | Prob (F-Statistic) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef | Prob. | Coef | Prob. | Coef | Prob. | Coef | Prob. | |||

| Per Country | ||||||||||

| Thailand | 0.226 | 0.001 | −0.171 | 0.013 | 0.2 | 0.000 | −0.082 | 0.136 | 0.073 | 0.000 |

| Malaysia | 0.132 | 0.006 | −0.18 | 0.000 | 0.107 | 0.008 | −0.036 | 0.385 | 0.033 | 0.000 |

| Indonesia | 0.022 | 0.836 | −0.25 | 0.019 | 0.212 | 0.020 | −0.164 | 0.069 | 0.09 | 0.005 |

| Per Year | ||||||||||

| 2023 | 0.09 | 0.084 | −0.158 | 0.003 | 0.136 | 0.002 | −0.015 | 0.741 | 0.031 | 0.000 |

| 2022 | 0.141 | 0.005 | −0.144 | 0.004 | 0.117 | 0.007 | −0.091 | 0.039 | 0.038 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pratama, A.; Afiah, N.N.; Ismail, R.F. Climate Change Management and Firm Value: Insights from Southeast Asia Markets (A Survey of Public Companies in Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand for the 2022–2023 Period). Sustainability 2025, 17, 4767. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114767

Pratama A, Afiah NN, Ismail RF. Climate Change Management and Firm Value: Insights from Southeast Asia Markets (A Survey of Public Companies in Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand for the 2022–2023 Period). Sustainability. 2025; 17(11):4767. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114767

Chicago/Turabian StylePratama, Arie, Nunuy Nur Afiah, and Rina Fadhilah Ismail. 2025. "Climate Change Management and Firm Value: Insights from Southeast Asia Markets (A Survey of Public Companies in Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand for the 2022–2023 Period)" Sustainability 17, no. 11: 4767. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114767

APA StylePratama, A., Afiah, N. N., & Ismail, R. F. (2025). Climate Change Management and Firm Value: Insights from Southeast Asia Markets (A Survey of Public Companies in Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand for the 2022–2023 Period). Sustainability, 17(11), 4767. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114767