1. Introduction

Pressure from competitors and regulatory intervention are external factors affecting hotels’ commitment to Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) initiatives [

1]. Top management commitment is a must for ESG initiatives [

2,

3]. It is a self-controllable factor. Entrepreneurial orientation has been studied in strategic corporate performance. It is an essential factor for making changes within the corporation in a rapidly changing world [

4]. Previous studies have investigated companies in various industries to examine the association between perceived entrepreneurial orientation and ESG performance [

5,

6]. Is there an association in the hospitality industry? What is the role of company size? This research makes a unique theoretical and managerial contribution to understand entrepreneurship and perceived ESG commitment in the hotel industry.

The hotel industry in Hong Kong is a vibrant and dynamic sector, which consists of a mix of international hotel brands contributing 57% of the total hotel properties and other domestic hotel brands. Hong Kong’s hotel market is forecast to achieve revenue of US

$1.49 billion in 2025 with an annual growth rate of 4.95%, leading to an estimated volume of US

$1.81 billion by 2026 [

7]. Along with hotels, Hong Kong also has guesthouses that provide budget accommodation to tourists [

8]. In total, the city is home to 330 hotels [

9]. International hotel brands have a significant presence in Hong Kong, with the major players Marriott International and Intercontinental Hotels Group leading the market. Marriott International operates 9 hotels with around 4500 rooms, while IHG has 12 hotels with approximately 3700 rooms [

10]. These international brands are known for their high standards of hospitality services to both business and leisure travelers. Other prominent international hotels, including the Ritz-Carlton, Four Seasons, Langham Hotels International, and the Mandarin Oriental, are well known for providing premier services to their guests. The hotel industry in Hong Kong looks promising due to the increase in overnight visitors, diversification of source markets, the city’s strategic location, robust infrastructure, and status as a global financial hub, making Hong Kong an appealing destination for both leisure and business travelers. Therefore, both international and domestic hotel brands are expected to play a crucial role in shaping the hospitality landscape of Hong Kong. This paper contributes new insights into the intersection of entrepreneurial orientation and ESG practices in the hospitality sector—a relatively understudied context.

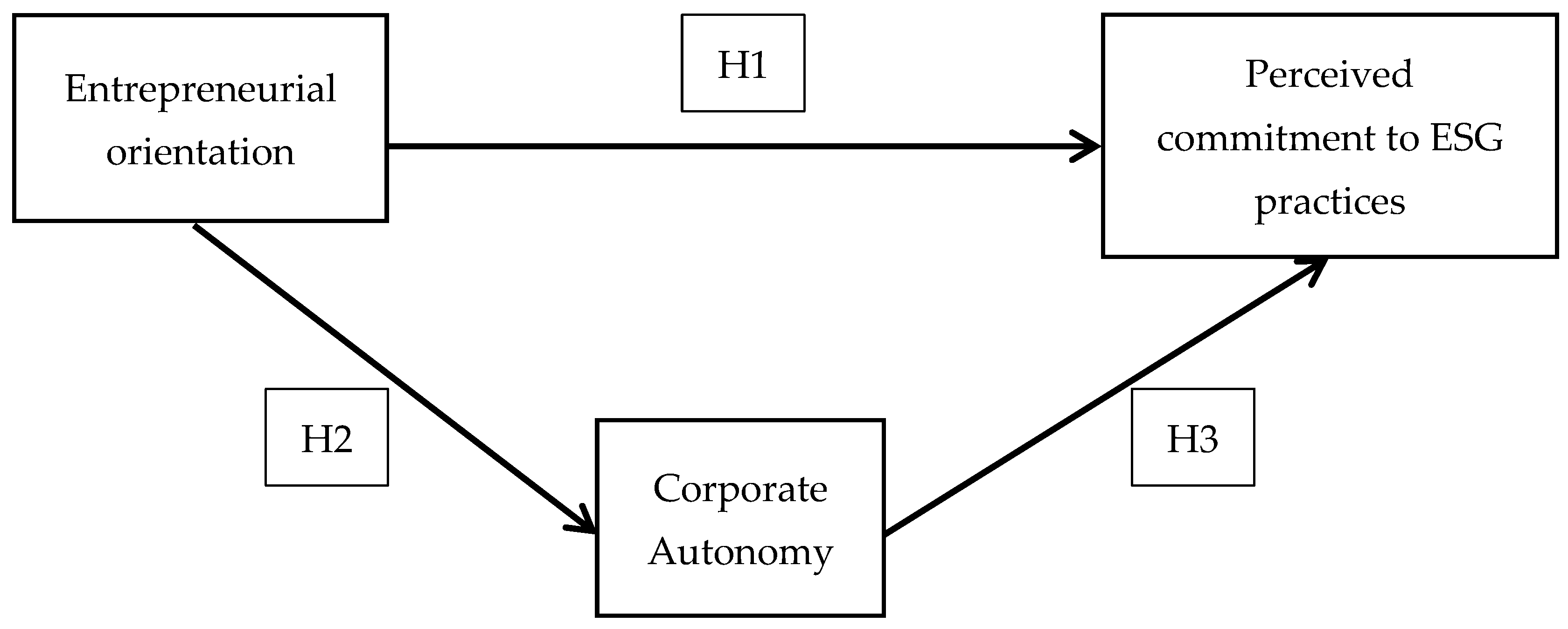

This research aimed to develop and test a proposed theoretical model to explain how perceived entrepreneurial orientation influences ESG commitment. Furthermore, we also examined the vital roles of the mediating role of corporate autonomy and the moderating role of company size on the association between perceived commitment to ESG practices and corporate financial performance. The perceived corporate financial performance is the corporate performance compared to the competitors.

2. Literature Review

Entrepreneurial orientation has been explored in the international business area in association with strategic performance [

4]. Recently, ESG performance has been linked to entrepreneurial orientation. A search using “entrepreneurial orientation and ESG performance” of the Scopus and Web of Science databases identified 16 journal articles devoted to this topic, half of them using ESG performance as the dependent variable (

Table 1). Digital transformation and technological innovation are common moderators in the relationship between perceived entrepreneurial orientation and ESG performance [

11,

12].

2.1. Resource-Based View of the Firm

This study adopted the resource-based view as its underpinning theoretical framework. It examined how hotels utilize their resources, as effective resource management often enables hotels to gain a competitive advantage. Consequently, this can lead to improved hotel performance [

15]. The resource-based view has previously been applied within the context of the hotel industry [

16]. Entrepreneurial orientation is considered one of the most critical intangible resources, as it drives innovation and changes in competitive markets. Furthermore, larger hotels typically possess greater resources, allowing for stronger commitments to ESG initiatives.

2.2. Association Between Perceived Entrepreneurial Orientation and Perceived Commitment to ESG Practices

Subsidiaries with higher entrepreneurial orientation (EO) typically strive to achieve higher strategic performance [

4]. Risk-taking can be defined as “willingness to commit a large amount of resources with a high chance of failure” ([

17], p. 1309). Innovativeness can be regarded as the eagerness to pursue novelty, whereby a company is “willing to support creativity... novelty, technological leadership, and R&D in developing a new process” ([

18], p. 431).

Regarding proactiveness, anticipating stakeholders’ expectations and voluntarily engaging in ESG practices are beneficial for companies. Usually, proactive ESG practices involve activities that are not legally required. Proactive ESG practices could give companies a competitive advantage, in contrast to passive ESG practices, which involve passively responding to stakeholders’ demands or merely complying with legal requirements [

19]. Undoubtedly, passive ESG practices do not offer companies a competitive advantage because stakeholders perceive such initiatives as obligatory rather than voluntary.

Innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking are the three components of the entrepreneurial orientation construct [

20]. However, the dependent variable of ESG commitment in this research cannot represent the entirety of commitment to ESG practices. Furthermore, ESG practices have also been associated with EO in the context of software companies, where ESG was treated as a single construct in the study [

21]. Thus, Hypothesis 1 was as follows:

H1:

Perceived EO is positively associated with perceived commitment to ESG practices.

2.3. Association Between Perceived Entrepreneurial Orientation and Corporate Autonomy

It is critical to recognize the underlying fundamental effects of perceived EO on company management prior to the generation of ESG practices and development of ESG standards. Firms demonstrating a strong desire to operate as creative, proactive, and risk-taking entrepreneurs to match industry and business development trends usually allow their employees greater autonomy to make decisions themselves [

22]. While many decisions originate from senior and top management, others can also be initiated from frontline positions and different units [

23], thereby granting a higher level of corporate autonomy. In the hotel and hospitality industry, not only multinational corporations but also small and medium-sized hotels have proactively taken actions to implement entrepreneurship. Ahmad [

24] highlighted that with self-confidence and perseverance, many hotel managers and owners managed to become relatively financially independent and autonomous in their operations and management. Additionally, entrepreneurial behavior tends to disrupt existing hotel practices and encourage innovation [

16]. Thus, the following hypothesis was proposed for the hotel industry:

H2:

Perceived EO is positively associated with perceived corporate autonomy.

2.4. Association Between Perceived Commitment to ESG Practices and Corporate Autonomy

The following discussion is based on the proposed relationship and rationale outlined above regarding ESG practice commitment. Corporations that are highly autonomous are believed to have greater flexibility in deciding how best to satisfy their own needs as well as those of others in corporate development [

25]. In fact, different stakeholders may attach importance to different value systems and strategic development goals, leading to different views on ESG practices and relevant policies. Autonomous firms, including hotels, are expected to make decisions and develop strategies more independently to pursue sustainability goals. In the hotel industry, if managers and employees have high autonomy to fulfill various requirements and standards, they tend to be more responsible for protecting the macro- and micro-environment of the hotel and demonstrate stronger commitment to ESG practices [

26]. Therefore, the following hypothesis was proposed for hotels:

H3:

Perceived corporate autonomy is positively associated with perceived commitment to ESG practices.

2.5. Association Between Perceived Commitment to ESG Practices and Corporate Financial Performance

There has been an emerging trend of conceptual and empirical studies examining the relationship between ESG practices and corporate financial performance. Saygili et al. [

27], for example, focused on Turkish listed companies and indicated that ESG practices exert an important influence on firm-level corporate financial performance. Meanwhile, proactive stakeholder involvement contributes significantly to the social dimension of ESG, enhancing firm performance. In the context of Indian companies, Dalal and Thaker [

28] concurred that investment in sustainability and corporate responsibility (i.e., addressing environmental, social, and governance domains) can translate into profitability, financial firm value, and long-term viability. A similar finding from Germany suggested that ESG practices can improve return on assets [

29].

Friede et al. [

30] consolidated findings from more than 2000 empirical studies and concluded broadly that investment in ESG practices, demonstrated by employee and corporate commitment to ESG implementation, has direct and positive impacts on corporate financial performance. Moreover, these financial benefits were found to persist over time in most cases. Furthermore, Lu et al. [

31] employed data from the hospitality sector from 2005 to 2022 to confirm the positive impact of ESG practices and commitment on corporate financial performance, including measures such as return on assets, Tobin’s Q, and return on equity. Given the above discussions, we proposed the following hypothesis to be tested in the hotel industry:

H4:

Perceived commitment to ESG practices is positively associated with corporate financial performance.

2.6. Association Between Perceived Entrepreneurial Orientation and Corporate Financial Performance

We also conceptualized the research model by directly linking the independent variable of perceived EO and the dependent variable of corporate financial performance. In our study, we believe entrepreneurial firms can achieve greater levels of performance and profitability through investments in innovation, risk-taking, and proactiveness in strategic planning and implementation. According to Rauch and Frese [

32], EO maintains firm-level strategic processes that lead to competitive firm advantages, paving the way for higher venture performance. Wales et al. [

33] provided solid evidence that EO has a direct relationship with firm performance, including financial performance. They surveyed Swedish small firms and found that mastering information and communication technologies and innovation capabilities can help enhance performance-related returns. These findings warrant the linkage between perceived EO and corporate financial performance.

Furthermore, this proposed relationship has been supported in the tourism industry overall [

34]. In the hotel industry context, for example, Vega-Vázquez et al. [

35] developed a mediation model between EO and corporate performance, with market orientation as the mediator. They suggested that hotel firms focus on market orientation to reinforce business performance outcomes. Going one step further, Momayet et al. [

36] argued that green EO has greater power in generating superior hotel performance. Given this discussion, we proposed and tested the following hypothesis in the hotel industry:

H5:

Perceived EO is positively associated with corporate financial performance.

2.7. Moderation Effect of Hotel Size on the Association Between Perceived ESG Practices and Perceived Corporate Financial Performance

According to Chen et al. [

37], company size impacts the relationship between ESG evaluation and corporate financial performance. Specifically, the relationship was non-significant for small-scale businesses but strong for large-scale businesses. Cautious implications were drawn for different company contexts. From the resource-based view of the firm, large companies may have more tangible and intangible resources dedicated to ESG practices, potentially enhancing corporate financial performance significantly. For example, large company employees may be permitted to participate in voluntary activities during office hours, a practice less feasible for small hotels [

38]. Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis for the hotel industry:

H6:

Corporate size moderates the association between perceived commitment to ESG practices and corporate financial performance.

2.8. Moderation Effect of Hotel Size on the Association Between Perceived ESG Practice and Entrepreneurial Orientation

When corporate size is large, it may be difficult for managers to innovate and be proactive. Staff in large companies often prefer following rules and taking fewer risks. Therefore, the association between entrepreneurial orientation and commitment to ESG practices may be weaker in large companies unless the chief executive officers are particularly proactive and aggressive [

6]. Thus, we proposed the following hypothesis for the hotel industry:

H7:

Corporate size negatively moderates the association between perceived entrepreneurial orientation and perceived commitment to ESG practices.

3. Materials and Methods

A focus group meeting with five senior managers was conducted earlier in 2025. The participants generally agreed that relationships may exist among entrepreneurial orientation, local commitment to ESG practices, corporate autonomy, and corporate financial performance variables. A quantitative method was employed for the main study, utilizing a survey format to collect data from hotel managers via Google Forms in March 2025. A purposive sampling method was applied, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Ethical approval was granted by the research committee prior to the commencement of the survey.

All constructs were derived from established scales. Perceived corporate autonomy is based on Edwards et al. [

39]. Perceived commitment to Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) practices is based on Courrent et al. [

40], Simberova et al. [

41], and Tricker [

42]. Entrepreneurial orientation is based on Lumpkin and Dess [

43] and Jambulingam et al. [

44] (

Appendix A). The wording was adapted to suit the hospitality industry. We used G*Power 3.1 to estimate the required sample size for four predictors and one dependent variable, assuming an effect size of 0.15 [

45]. After calculation, the required sample size was determined to be 89. We ensured our final sample was large enough to predict meaningful associations with sufficient statistical power.

Since hotel managers provided responses for both the dependent and independent variables, there was a potential risk of common method bias. To address this, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted, revealing that the total variance explained was below the 50% threshold [

46]. This result indicates that common method bias was not a concern [

47,

48]. Furthermore, the correlations between constructs were all below 0.9 [

49], providing additional evidence that common method bias did not affect the results.

Perceived entrepreneurial orientation consists of three dimensions: innovativeness, risk-taking, and proactiveness, while perceived corporate autonomy is measured as a single-dimensional construct. Perceived commitment to ESG practices captures the level of engagement in these practices. Firm size acts as a moderating factor, while tenure and position level were included as control variables.

Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was selected for the analysis due to the presence of multiple independent and dependent variables. This method is particularly advantageous as it does not require distributional assumptions about the data, allows for causal predictions, and is well suited for generating managerial implications [

50].

4. Results

Table 2 presents the respondents’ profile in this study. All participants were over 18. There are 330 hotels and some guesthouses in Hong Kong. A total of 400 emails were sent out to hotels in Hong Kong. Following the distribution of reminders, a total of 120 complete responses were collected, resulting in a response rate of 30%, which is consistent with similar studies in business research. Participants were not offered any incentives for their involvement. Notably, the 120 responses exceeded the minimum required sample size of 89.

A total of 47.5% of our sample was male. Most respondents were aged between 18 and 50. Almost all respondents worked in large hotels with more than 100 employees. All respondents held supervisory positions or higher, ensuring awareness of their corporate situation. Most respondents had worked for their current employers for more than two years (

Table 2).

4.1. Measurement Model

The measurement model was assessed using average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability, and Cronbach’s alpha.

Table 3 presents the assessments of the lower-order constructs, while

Table 4 provides the assessments of the higher-order constructs.

The composite reliability values for all constructs were above 0.70, demonstrating strong reliability. Cronbach’s alpha was used to evaluate internal consistency, with all values exceeding 0.708. Furthermore, the average variance extracted (AVE) values for all constructs were greater than 0.50, confirming convergent validity. Discriminant validity was evaluated using the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio, with all values below the 0.85 threshold. HTMT is considered more robust than the Fornell-Larcker criterion for testing discriminant validity [

50] (

Table 5). Based on these results, the measurement model was deemed acceptable for further analysis [

50]. There were two higher-order constructs: perceived ESG commitment and entrepreneurial orientation. The composite reliability values of these higher-order constructs was between 0.70 and 0.95, ensuring strong reliability without data redundancy [

50].

4.2. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

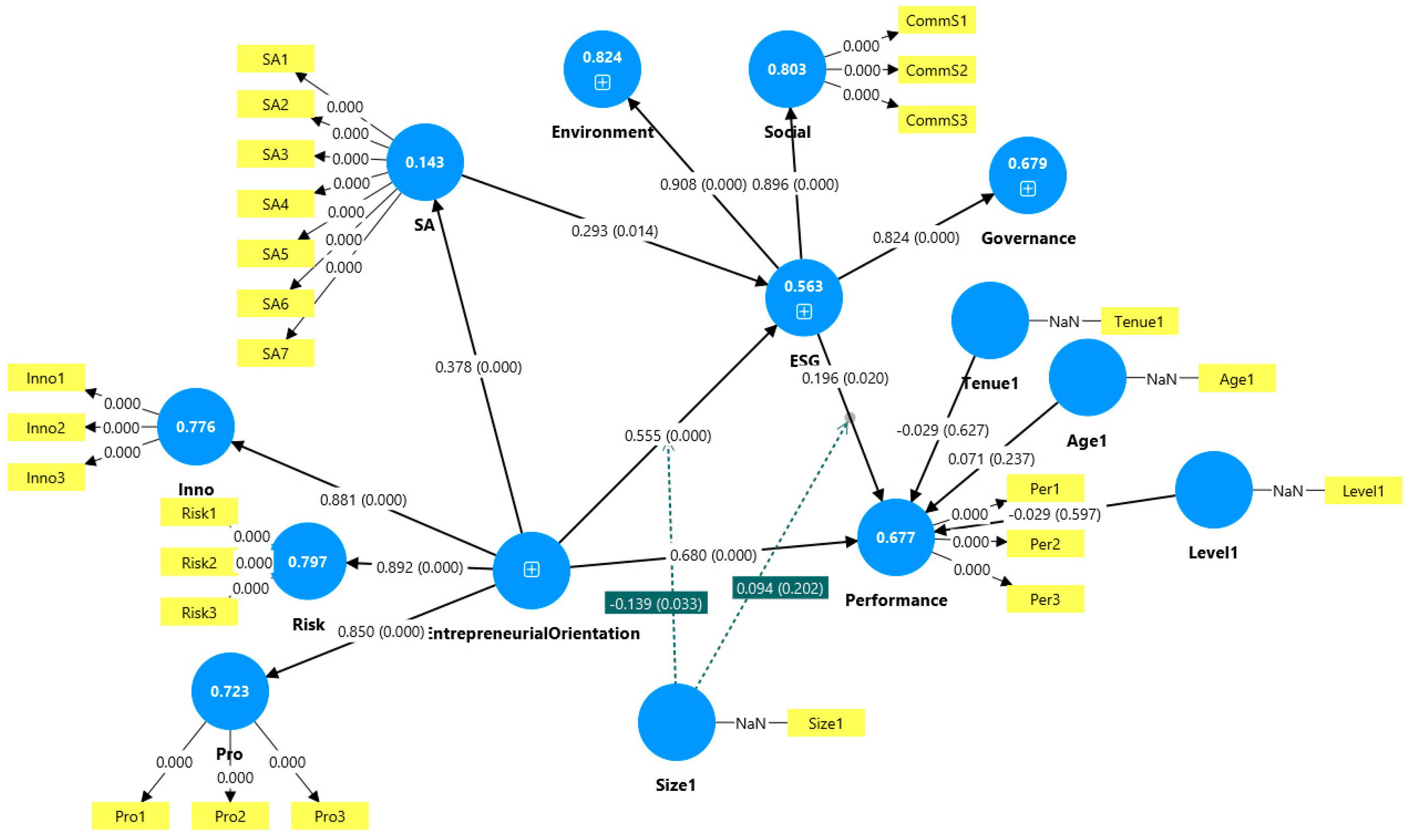

The hypothesis testing results are presented in

Table 6. All hypotheses were supported, except for Hypothesis 6. The effect sizes were found to be large for the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and perceived ESG commitment, as well as for the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and perceived corporate performance. Medium effect sizes were observed for the associations between entrepreneurial orientation and corporate autonomy, and between corporate autonomy and perceived ESG commitment.

Age, tenure, and managerial level were the control variables for corporate performance. The rationale is that managers at higher levels usually have more experience and are older, so they may know more about perceived corporate performance. Based on the results presented in

Table 6, entrepreneurial orientation is positively associated with corporate financial performance, commitment to ESG practices, and corporate autonomy. In addition, commitment to ESG practices is positively associated with corporate financial performance and corporate autonomy.

Our findings indicate that entrepreneurial orientation explains 14.3% of the variance in corporate autonomy, while corporate autonomy and entrepreneurial orientation together account for 56.3% of the variance in commitment to ESG practices. Moreover, 67.7% of the variance in corporate financial performance is explained by commitment to ESG practices and entrepreneurial orientation (

Figure 1). Perceived entrepreneurial orientation has a large effect size on both corporate financial performance and commitment to ESG practices. It also has a medium effect size on corporate autonomy, while corporate autonomy exhibits a medium effect size on commitment to ESG practices. Lastly, commitment to ESG practices demonstrates a small effect size on corporate financial performance [

51].

4.3. Robust Tests

We performed robustness checks. First, a confirmatory tetrad analysis was conducted to ensure the validity of the reflective measurements. Second, nonlinear effects were checked, and we found none in the model. Third, endogeneity was assessed using the Gaussian copula approach [

52]. Finally, partial data were checked for unobserved heterogeneity [

50].

5. Discussion

Our findings indicate a positive association between entrepreneurial orientation and commitment to ESG practices (Hypothesis 1). This suggests that key dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation, including innovation, risk-taking, and proactiveness, play a critical role in fostering commitment to ESG practices. Our research concurs with previous findings from the financial and manufacturing industries regarding the relationship between perceived entrepreneurial orientation and commitment to ESG practices [

3].

Entrepreneurial orientation is positively associated with corporate autonomy (Hypothesis 2) in Hong Kong hotels. This finding is similar to that of Hossain et al. [

16]. Additionally, our results reveal that perceived corporate autonomy is positively associated with commitment to ESG practices (Hypothesis 3). Wut et al. [

3] reported similar findings in the financial and manufacturing industries.

Our results also suggest that perceived commitment to ESG practices is positively related to corporate financial performance (Hypothesis 4), aligning with the findings of Lu et al. [

31] in the hospitality industry. Moreover, we verified the findings of Vega-Vázquez et al. [

35] regarding the positive association between perceived entrepreneurial orientation and corporate financial performance among hotels in Hong Kong (Hypothesis 5).

The effect size for Hypothesis 5 was larger than for Hypothesis 4. Perceived entrepreneurial orientation has a greater impact on perceived corporate financial performance compared to ESG commitment. Since entrepreneurial orientation comprises three dimensions—risk-taking, innovativeness, and proactiveness—these elements significantly contribute to improved strategic performance [

4]. In contrast, perceived ESG commitment is just one among many factors influencing perceived corporate financial performance.

While five direct hypotheses were supported, the moderating effect of company size on the relationship between commitment to ESG practices and perceived corporate financial performance (Hypothesis 6) was not confirmed. This finding may be attributed to the fact that the majority of the respondents were employed in large hotels. Also, small hotels are profitable after COVID, and they have resources comparable to larger hotels. However, the negative moderating effect of company size on the relationship between perceived entrepreneurial orientation and commitment to ESG practices (Hypothesis 7) was found to be significant. Building on these findings, this study advances the existing body of literature by providing a nuanced examination of these relationships within the specific context of the hotel industry.

Perceived commitment to ESG practices served as a partial mediator in the link between entrepreneurial orientation and perceived corporate financial performance. This finding is supported by the significant direct effect of entrepreneurial orientation on perceived corporate financial performance, along with the significant indirect effect mediated through perceived commitment to ESG practices (

Figure 2).

Similarly, perceived corporate autonomy acted as a partial mediator in the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and perceived commitment to ESG practices. This mediation was supported by the significant direct effect of entrepreneurial orientation on perceived commitment to ESG practices, as well as the significant indirect effect from entrepreneurial orientation to perceived commitment to ESG practices via corporate autonomy (

Figure 3).

In addition, there was a serial mediation incorporating both mediators mentioned above (

Figure 4). Corporate autonomy and perceived commitment to ESG practices partially mediated the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and perceived corporate financial performance.

6. Conclusions

This study provides a solid understanding of the relationships among perceived entrepreneurial orientation, corporate autonomy, commitment to ESG practices, and corporate financial performance. Perceived entrepreneurial orientation has a larger effect on corporate financial performance than commitment to ESG practices. The results revealed the partial mediation effects of corporate autonomy and commitment to ESG practices. The moderating effect of corporate size revealed that hotel size does not influence how commitment to ESG practices affects corporate financial performance in the hotel industry. In contrast, hotel size influences how entrepreneurial orientation impacts concern for the environment and society. In other words, small hotels are more likely to exhibit entrepreneurial behavior and demonstrate commitment to environmental and social concerns when granted greater autonomy in decision-making. However, being entrepreneurial and committed to environmental and social concerns does not significantly affect financial performance, regardless of hotel size.

Our study provides practical implications for top hotel management to consider the relevance of entrepreneurial orientation and corporate autonomy on perceived commitment to ESG practices. Managers are advised to be more proactive and innovative. Staff should be given more flexibility to propose and implement ESG practices to respond to local stakeholders’ expectations, including providing more job opportunities for persons with disabilities. Policymakers, including regulators, could encourage more new initiatives from hotels besides corporate donations. Additionally, policymakers could impose extra taxes on hotel usage, so that more resources can be allocated to environmental measures. Given the alignment of these measures with sustainability objectives, their potential to contribute positively to sustainable development is evident.

This study is subject to several limitations. First, the use of a non-probability sampling technique may restrict the generalizability of the findings to the broader hotel industry. Second, while this study employed a cross-sectional design, a longitudinal approach could provide deeper insights by capturing the temporal dynamics of perceived corporate financial performance, which often materializes over time. Third, the study relied on perceived corporate financial performance rather than objective performance metrics, making the results dependent on hotel managers’ recollections, which may not fully align with actual performance outcomes. Finally, the partial least squares method is predictive in nature and sensitive to outliers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M.W.; methodology, T.M.W.; software, T.M.W.; validation, T.M.W.; formal analysis, T.M.W.; investigation, T.M.W.; resources, H.S.-M.W. and T.M.W.; data curation, E.A.-H.C.; writing—original draft preparation, T.M.W.; writing—review and editing, T.M.W., J.B.X. and S.W.L.; visualization, T.M.W.; supervision, H.S.-M.W.; project administration, E.A.-H.C.; funding acquisition, T.M.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the College of Professional and Continuing Education (UGC/IIDS24/B03/24).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The ethical review for research was approved by the College of Professional and Continuing Education committee (RC/ETH/H/282).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data can be requested from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Measurement scales (sample items).

Table A1.

Measurement scales (sample items).

| Construct | Measurement Items | Source |

|---|

| Perceived Corporate Autonomy | My hotel has decision power of setting budgets. My hotel has decision power of marketing activities. My hotel has decision power of setting prices of products/services. My hotel has decision power of development of new products/services. My hotel has decision power of selecting suppliers. My hotel has decision power of setting service process. My hotel has monitoring and controlling power of products/services.

| Edward et al., 2002 [39]. |

| Perceived Local Commitment to Environmental Practices | My hotel has established metrics to monitor, such as environmental risk, pollution risk, energy saving, and waste. My hotel communicates environmental actions to us. My hotel communicates environmental actions to our customers, suppliers, and other people in local community.

| Courrent et al., 2018 [40]. |

| Perceived Local Commitment to Social Practices | My hotel contributes to community cultural, sporting, and/or educating activities. My hotel consults stakeholders for our decisions concerning local community development. My hotel offers internships and contributes to local student training.

| Courrent et al., 2018 [40]. |

| Perceived Local Commitment to Governance Practices | As a responsible company, my hotel favors more women as members of the board of directors. As a responsible company, my hotel favors an independent non-executive director as chairman of the board of directors. As a responsible company, my hotel favors that the CEO is not the chairman of the board of directors.

| Simberova et al., 2012 [41]; Tricker, 2015 [42]. |

| Perceived Entrepreneurial Orientation | InnovativenessOur hotel is known as an innovator among businesses in our industry. We promote new innovate products/services in our hotel. Our hotel provides leadership in developing new products/services.

Risk-takingTop managers of our hotel tend to invest in high-risk projects. This hotel shows a great deal of tolerance for high-risk projects. Our business strategy is characterized by a strong tendency to take risks.

ProactiveWe seek to exploit anticipated changes in our target market ahead of our rivals. We take hostile steps to achieve competitive goals in our target markets. Our actions toward competitors can be termed as aggressive.

| Lumpkin & Dess, 1996 [43]; Jambulingam et al., 2005 [44]. |

References

- Dahlstrom, R.; Haugland, S.; Nygaard, A.; Rokkan, A. Governance structures in the hotel industry. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Jia, M. Echoes of CEO Entrepreneurial Orientation: How and When CEO Entrepreneurial Orientation Influences Dual CSR Activities. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 169, 609–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wut, T.M.; Wong, H.; Chan, E. Perceived multinational subsidiary autonomy and local commitment to corporate social responsibility in China. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2024, 30, 100352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Guo, A. When and How Institutions Matter in Entrepreneurship and Strategic Performance; South-East Asia Chapter; Academy of International Business Conference: Cebu, Philippines, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Drobetz, W.; Ghoul, S.; Guedhami, O.; Hackmann, J.; Momtaz, P. Entrepreneurial finance and sustainability. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2024, 22, e00498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, Y. Analyzing factors that affect Korean B2B companies’ sustainable performance. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Hotels–Hong Kong. 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/mmo/travel-tourism/hotels/hong-kong (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Statista. Hotel Industry in Hong Kong–Statistics & Facts. 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/8170/hotel-industry-in-hong-kong/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Blazyte, A. Number of Hotels and Guesthouses in Hong Kong, Statista. 2025. Available online: www.statista.com (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Mordor Intelligence. Hong Kong Hospitality Industry Size & Share Analysis–Growth Trends & Forecasts (2025–2030). 2025. Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/hospitality-industry-in-hong-kong (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Yadav, U.; Ghosal, I.; Pareek, A.; Khandelwai, K.; Yadak, A.; Chakraborty, C. Impact of entrepreneurial orientation and ESG on environmental performance: Moderating impact of digital transformance and technological innovation as a mediating construct using Sobel test. J. Innov. Entrep. 2024, 13, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, E.; Otto, J.; Wirsching, K. Entrepreneurial universities and the third mission paradigm shift from economic performance to impact entrepreneurship. J. Technol. Transf. 2024, 49, 2184–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gega, M.; Hohler, J.; Bijman, J.; Lansink, A. Firm ownership and ESG performance in European agri-food companies: The mediating effect of risk-taking and time horizon. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 1161–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hu, H.; Wang, X. Green entrepreneurship orientation and environmental, social and governance performance: Do contractual strategic alliances matter? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 5275–5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B. A resource-based view of the firm. Birger Wernerfelt Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Hussain, K.; Kannan, S.; Nair, S. Determinants of sustainable competitive advantage from resource-based view: Implications for hotel industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2022, 5, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J.; Shepherd, D. Knowledge-based Resources, Entrepreneurial Orientation, and the Performance of Small and Medium-ized Businesses. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 1307–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G. Linking Two dimensions of Entrepreneurial Orientation to Firm Performance: The Moderating role of Environment and Industry Life Cycle. J. Bus. Ventur. 2001, 16, 429–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Consumer Responses to the Food Industry’s Proactive and Passive Environmental CSR, Factoring in Price as CSR tradeoff. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wut, T.M. Discourse patterns used in CSR reporting. In Proceedings of the PolyU SPEED—UNN NBS Joint Conference, Newcastle, UK, 14 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, L. Organizational Ambidexterity, Entrepreneurial Orientation, and I-Deals: The moderating role of CSR. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wales, W.J. Entrepreneurial orientation: A review and synthesis of promising research directions. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2016, 34, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgelman, R.A. A process model of internal corporate venturing in the diversified major firm. Adm. Sci. Q. 1983, 28, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.Z. Entrepreneurship in the small and medium-sized hotel sector. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 328–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, J.; Bailey, N. Constructs and measures in the stakeholder management research. In Business and Management; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Gao, Y.; Thomas, N. Enhancing tourism and hospitality organizations’ ESG via transformational leadership and employee pro-environmental behavior: The effect of organizational culture. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 124, 103970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saygili, E.; Arslan, S.; Birkan, A.O. ESG practices and corporate financial performance: Evidence from Borsa Istanbul. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2022, 22, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, K.K.; Thaker, N. ESG and corporate financial performance: A panel study of Indian companies. IUP J. Corp. Gov. 2019, 18, 44–59. [Google Scholar]

- Velte, P. Does ESG performance have an impact on financial performance? Evidence from Germany. J. Glob. Responsib. 2017, 8, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Onuk, C.B.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, J. ESG ratings and financial performance in the global hospitality industry. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2025, 18, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Frese, M. Entrepreneurial orientation. In Handbook Utility Management; Bausch, A., Schwenker, B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Wales, W.J.; Patel, P.; Parida, V.; Kreiser, P.M. Nonlinear effects of entrepreneurial orientation on small firm performance: The moderating role of resource orchestration capabilities. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2013, 7, 93–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadda, N. The effects of entrepreneurial orientation dimensions on performance in the tourism sector. New Engl. J. Entrep. 2019, 21, 22–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Vázquez, M.; Cossío-Silva, F.; Revilla-Camacho, M. Entrepreneurial orientation–hotel performance: Has market orientation anything to say? J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5089–5094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momayet, A.; Rasouli, N.; Alimohammadirokni, M.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M. Green entrepreneurship orientation, green innovation and hotel performance: The moderating role of managerial environmental concern. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2023, 32, 981–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Song, Y.; Gao, P. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance and financial outcomes: Analyzing the impact of ESG on financial performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.; Holladay, S. Managing Corporate Social Responsibility; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RAhmad, A.; Moss, S. Subsidiary Autonomy: The case of Multinational Subsidiaries in Malaysia. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2002, 33, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courrent, J.; Chasse, S.; Omri, W. Do Entrepreneurial SME’s perform better because they are more responsible? J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 153, 317–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simberova, I.; Kocmanova, A.; Nemecek, P. Corporate Governance Performance Measurement–Key Performance indicators. Econ. Manag. 2012, 17, 1585–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricker, B. Corporate Governance; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambulingam, T.; Kathuria, R.; Doucette, W.R. Entrepreneurial orientation as a basis for classification within a service industry: The case of retail pharmacy industry. J. Oper. Manag. 2005, 23, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Ardura, I.; Messeguer-Artola, A. How to prevent, detect and control common method variance in electronic commerce research. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 15, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M.; Olya, H. The combined use of symmetric and asymmetric approaches: Partial least squares-structural equation modelling and fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 1571–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hult, G.; Hair, J.; Proksch, D. Addressing endogeneity in international marketing application of partial least squares structural equation modelling. J. Int. Mark. 2018, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).