Multinomial Logistic Analysis of SMEs Offering Green Products and Services in the Alps–Adriatic Macroregion

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We isolate this (post)transitional group of SMEs in a specific region and show its distinct drivers;

- We introduce the green jobs intensity variable to test its incremental effect;

- We provide the cross-country comparison within the Alps–Adriatic macro-region.

- RQ1. How does engagement in resource-efficiency actions affect an SME’s likelihood to offer (or plan to offer) green products/services?

- RQ2. How does the share of green jobs within an SME influence that likelihood?

- RQ3. Are there unspecified heterogeneities in green offer across the five Alps–Adriatic countries?

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Green Products and Services

2.2. Green Jobs

2.3. Resource Efficiency

2.4. Managerial Motives and Policy Incentives

- Cost savings via reduced energy and material expenditures [14];

- Stakeholder and market pull, with green offerings strengthening the brand image and meeting customer demand [22];

- Access to external support, including financial incentives, technical consultancy, and market-identification assistance [18];

- Regulatory compliance under EU and national directives on resource efficiency [3].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Hypotheses

4. Results

5. Discussion

- SME managers should coordinate multiple measures (energy, waste, water, design) to surpass the capability threshold that unlocks green product/service offerings.

- As market-identification aid yield the largest RRR (2.34) and financial incentives the second (2.26), firms should actively seek grants and consultancy programs.

- Building green job intensity fosters innovation routines and sustains green offerings.

- Policymakers should integrate grant funding with hands-on advisory services and tailor outreach to service-only SMEs, which lag behind product-oriented peers.

- Causality cannot be inferred due to the study’s cross-sectional design; panels or experiments are needed to validate directional effects.

- We use a secondary data source and, thus, rely on the existing survey data from the Eurobarometer. In future studies, research might wish to develop original survey instruments.

- Detailed subsector or thematic case studies (e.g., tourism vs. manufacturing services) should be performed to provide an in-depth analysis of the “service-only” firms.

- Follow-up studies should explore mixes of national policy and cultural factors underlying the heterogeneity among the five countries.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SMEs | Small and medium-size enterprises |

| RRR | Relative risk ratio |

Appendix A

| N | 2305 |

| Does your company offer green products or service? (Dependent variable) | |

| Yes—1 No, but you are planning to do so in the next 2 years—2 No, and you are not planning to do so—3 (base outcome) | 818 (34.0%) 308 (12.8%) 1281 (53.2%) |

| Independent variables | |

| What actions is your company undertaking to be more resource-efficient? | |

| 0—no action | 138 (5.8%) |

| 1—few actions (1–2 selected activities) | 508 (21.3%) |

| 2—some actions (3–4 selected activities) | 796 (33.4%) |

| 3—many actions (5 or more than 5 selected activities) | 942 (39.5%) |

| What additional resource efficiency actions will your company plan to implement over the next two years? | |

| 0—no action | 467 (20.1%) |

| 1—few actions (1–2 selected activities) | 498 (21.4%) |

| 2—some or many actions (3 or more selected activities) | 1362 (58.5%) |

| Are financial incentives for developing products, services, or new production processes needed? | 1069 (44.4%) |

| Assistance with identifying potential markets or customers needed? | 432 (17.9%) |

| Is technical support and consultancy needed for the development of products, services, and production processes? | 553 (23.0%) |

| Consultancy services needed for marketing or distribution? | 386 (16.0%) |

| The ratio between employees’ full time equivalent and full-time employees working in green jobs some or all of the time | |

| ≥0 and ≤5% (base value) | 1395 (58.0%) |

| >5% and ≤10% | 120 (5.0%) |

| >10% and ≤30% | 228 (9.5%) |

| >30% and ≤100% | 664 (27.6%) |

| Industry | |

| 0—Manufacturing (C), Services (H/I/J/K/L/M) or Industry (B/D/E/F) | 1689 (70.2%) |

| 1—Retail (G) | 718 (29.8%) |

| Country | |

| Croatia (base category) | 461 (19.2%) |

| Italy | 502 (20.9%) |

| Hungary | 471 (19.6%) |

| Austria | 445 (18.5%) |

| Slovenia | 528 (21.9%) |

| Is your company selling services? | |

| No | 1496 (62.2%) |

| Yes | 911 (37.8%) |

| Is your company selling its products or services to other companies? | |

| Yes | 599 (24.9%) |

| No | 1808 (75.1%) |

Appendix B

| Variable | VIF | Variable | VIF | Variable | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| re_present | sup_fin = 1 | 1.06 | nace = 1 | 1.11 | |

| 1 | 3.96 | sup_mark = 1 | 1.06 | ipscntry = 12 | 1.89 |

| 2 | 4.97 | sup_tech = 1 | 1.07 | 17 | 1.71 |

| 3 | 4.39 | sup_cons = 1 | 1.07 | 20 | 1.73 |

| re_plan | green_job = 10 | 1.07 | 24 | 1.69 | |

| 1 | 1.91 | 30 | 1.09 | serv = 1 | 1.11 |

| 2 | 1.89 | 100 | 1.13 | b2b = 1 | 1.02 |

| Mean VIF = 1.89 | |||||

| N = 2305; df = 20 | Hausman Test | Suest–Based Hausman Tests | Small–Hsiao Tests Set Seed 1673029581 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternatives | chi2 | P > chi2 | chi2 | P > chi2 | ||||

| 1 | 6.208 | 0.999 | 27.879 | 0.112 | −328.641 | −317.581 | 22.120 | 0.334 |

| 2 | 7.732 | 0.993 | 28.063 | 0.108 | −572.194 | −561.634 | 21.119 | 0.390 |

| 3 | 18.195 | 0.575 | 41.540 | 0.003 | −274.385 | −263.151 | 22.469 | 0.316 |

| Ho: Odds (Outcome-J Vs. Outcome-K) are independent of other alternatives | ||||||||

References

- IPCC. Sections. In Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 35–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. UN Sustainable Development Goals: Quality Education; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-consumption-production/ (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Katsinis, A.; Lagüera-González, J.; Di Bella, L.; Odenthal, L.; Hell, M.; Lozar, B. Annual Report on European SMEs 2023/2024; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bătrâncea, L.M. Determinants of economic growth across the European Union: A panel data analysis on small and medium enterprises. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lems, A. Anti-mobile placemaking in a mobile world: Rethinking the entanglements of place, im/mobility and be-longing. Mobilities 2023, 18, 620–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grulja, M.A.; Turk, T.; Verbič, M. Taxation of wages in the Alps-Adriatic region. Financ. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alps-Adriatic Alliance. About Us; Alps-Adriatic Alliance: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://alps-adriatic-alliance.org/about/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Lipott, S. Cross-Border Aspects of Regional Governance in the Alps—Adriatic Borderlands: From Euro Regional Experiences to EGTC Prospects. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Grenoble, Grenoble, France, 2013. Available online: https://static.uni-graz.at/fileadmin/veranstaltungen/twenty-five-years-after/abstracts_program/RESEARCH_Sigrid_Lipott_Graz.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Parry, G.; Newnes, L.; Huang, X. Goods, products and services. In Service Design and Delivery; Parry, G., Newnes, L., Huang, X., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- GESIS. Flash Eurobarometer 498 (SMEs, Resource Efficiency and Green Markets, Wave 5); GESIS Data Archive: Cologne, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendoorn, B.; Guerra, D.; Van Der Zwan, P. What drives environmental practices of SMEs? Small Bus. Econ. 2015, 44, 759–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, D.; Van der Vorst, R. Developing sustainable products and services. J. Clean. Prod. 2003, 11, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwandani, J.A.; Michaud, G. What are the drivers and barriers for green business practices adoption for SMEs? Environ. Syst. Decis. 2021, 41, 577–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Structural Business Statistics Overview. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Structural_business_statistics_overview (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Oduro, S. Eco-innovation and SMEs’ sustainable performance: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2024, 27, 248–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manta, O.; Mansi, E. The impact of globalization on innovative public procurement: Challenges and opportunities. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achmad, N.G.; Yudaruddin, R.; Nagroho, B.A.; Fitian, Z.; Suharsono, S.; Adi, A.S.; Hafsari, P.; Fitriansyah, F. Government support, eco-regulation and eco-innovation adoption in SMEs: The mediating role of eco-environmental. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9, 100158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, R.D.; Benfica, V.C.; de Oliveira, H.V.E.; Suchek, N. Investigating green jobs and sustainability in SMEs: Beyond business operations. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 486, 144477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedefop. Digital, Greener and More Resilient: Insights from Cedefop’s European Skills Forecast; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chaparro-Benegas, N.; Mas-Tur, A.; Park, N.W.; Roig-Tierno, N. Factors driving national eco-innovation: New routes to sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 2711–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrilli, M.D.; Balavac Orlić, M.; Radičić, D. Environmental innovation across SMEs in Europe. Technovation 2023, 119, 102624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, M.; Sweeney, S.; Kubit, J. Green Jobs: Towards Decent Work in a Sustainable, Low-Carbon World; Worldwatch Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cedefop. The Green Employment and Skills Transformation: Insights from a European Green Deal Skills Forecast Scenario; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpellini, S.; Ortenga-Lapiedra, R.; Marco-Fondevila, M.; Andra-Uson, A. Human capital in the eco-innovative firms: A case study of eco-innovation projects. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 919–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyensare, M.A.; Adomako, S.; Amankwah-Amoah, J. Green HRM practices, employee well-being, and sustainable work behavior: Examining the moderating role of resource commitment. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 3129–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahn-Walkowiak, B.; Wilts, H. The institutional dimension of resource efficiency in a multi-level governance system—Implications for policy mix design. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 33, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, N.; Haleem, A. Exploring the nexus of eco-innovation and sustainable development: A bibliometric review and analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vučković, V.; Čučković, N. Greening of SMEs in Western Balkan countries—Evidence from firm-level analysis. Econ. Ann. 2024, 69, 7–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.J.; Stephens, J.C. Energy democracy: Goals and policy instruments for sociotechnical transitions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 33, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triguero, A.; Cuerva, M.; Sáez-Martínez, F. Closing the loop through eco-innovation by European firms: Circular economy for sustainable development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 2337–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, S.; Zhang, X.; Khaskheli, M.B.; Hong, F.; King, P.J.H.; Shamsi, I.H. Eco-efficiency, environmental and sustainable innovation in recycling energy and their effect on business performance: Evidence from European SMEs. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilescu, M.D.; Dimian, G.C.; Grădinaru, G.I. Green entrepreneurship in challenging times: A quantitative approach for European countries. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraž. 2023, 36, 1828–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoungman, F.Z.; Islam, M.S.; Masukujjaman, M.; Shawon, A.H.; Al Mahmud, A. Financial factors influencing investment willingness in environment-friendly business: Empirical study on an emerging economy. Innov. Green Dev. 2025, 4, 100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, S.; Tian, H.; Iqbal, S.; Hussain, R.Y. Environmental regulations and government support drive green innovation performance: Role of competitive pressure and digital transformation. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2024, 26, 4433–4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Lei, M.; Xu, X. Green production willingness and behavior: Evidence from Shaanxi apple growers. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hoejmose, S.; Brammer, S.; Millington, A. “Green” supply chain management: The role of trust and top management in B2B and B2C markets. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2012, 41, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, F.; Dias, J.G. The use of circular economy practices in SMEs across the EU. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.S.; Freese, J. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata; Stata Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, W.H.; Chidlow, A.; Strange, R. The use of multinomial choice analysis in international business research. Int. Bus. Rev. 2022, 31, 102011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Has, M.; Alpeza, M. Human Resource Management in Small Enterprises: Findings from Croatia. Management 2024, 29, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashne, L.; Baracskai, Z. Senior Management Mindsets for Corporate Social Responsibility. Management 2024, 29, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Term | Operational Definition (Source) |

|---|---|

| Green product | A tangible good whose primary purpose is to reduce environmental risks and minimize resource use across its life cycle [11]. |

| Green service | An intangible offering designed and delivered with measurably lower environmental impact relative to the conventional alternative [11]. |

| Green job | A position in which ≥50% of working time is devoted to activities that improve resource efficiency or lower emissions [19]. |

| Resource-efficiency action (REA) | Any of the nine practices in Eurobarometer Q6–Q7 (energy saving, water saving, … circular design) [11]. |

| Country | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Croatia | 461 | 20.0 |

| Italy | 502 | 21.8 |

| Hungary | 471 | 20.4 |

| Austria | 445 | 19.3 |

| Slovenia | 528 | 22.9 |

| Sector | N | % |

| Retail (NACE G) | 718 | 31.1 |

| Manufacturing and Services | 1587 | 68.9 |

| Sell only services | N | % |

| Yes | 911 | 39.5 |

| No | 1394 | 60.5 |

| B2B focus | N | % |

| Yes | 1808 | 78.5 |

| No | 497 | 21.5 |

| Tests | Extended (Initial) Model | Reduced (Final) Model |

|---|---|---|

| Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) | 4080.684 | 4034.298 |

| Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) | 4563.083 | 4264.011 |

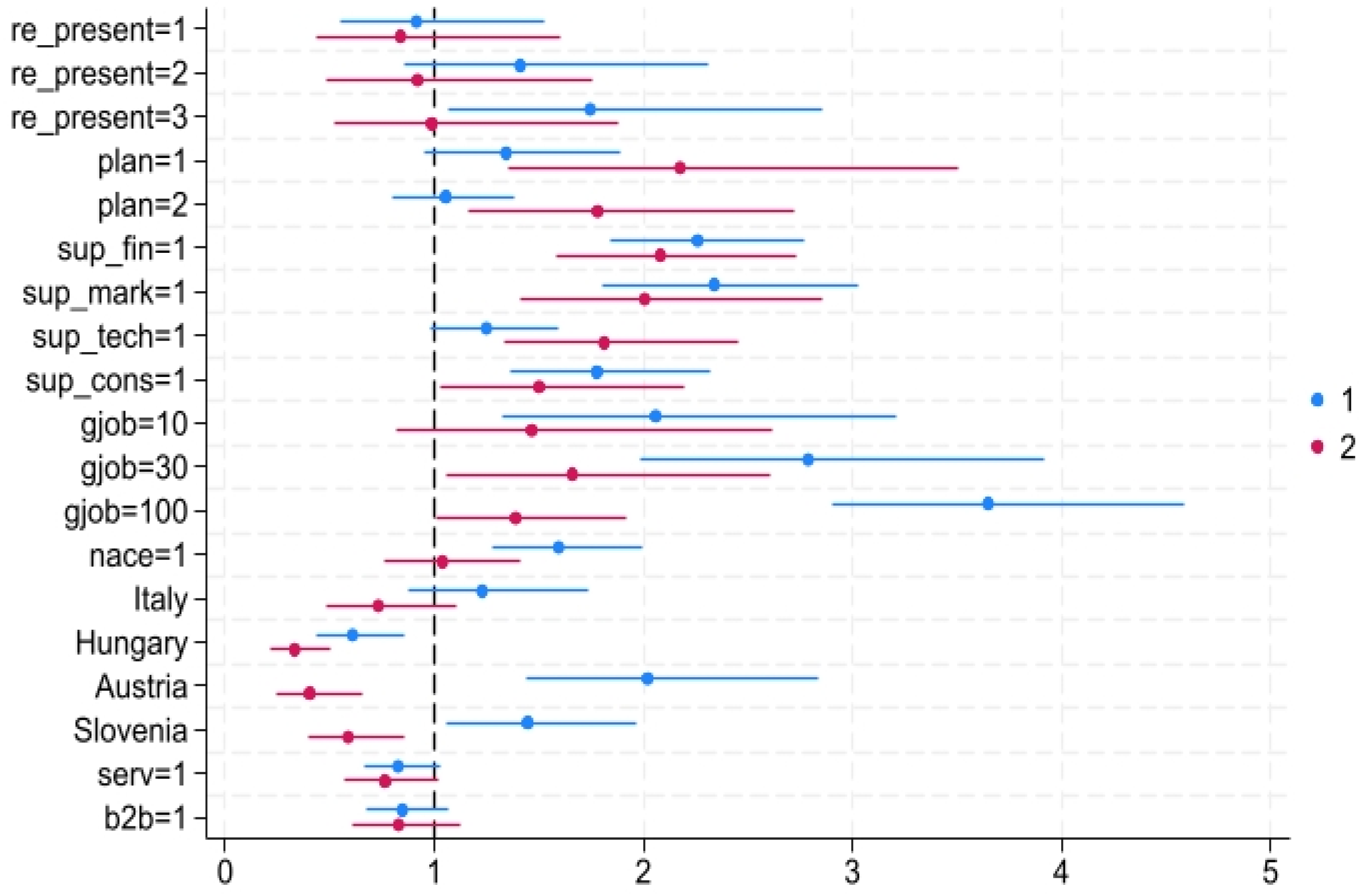

| Base Outcome: 3 = Not Offering and Not Planning to Offer Green Products/Services | (1 = Yes) | (2 = No, but Planning) | (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Coefficient | RRR | RRR | ||

| Present resource | Few actions (1–2) | −0.0891 | −0.176 | 0.915 | 0.839 |

| efficiency | (re_present = 1) | (0.261) | (0.331) | (0.238) | (0.278) |

| base: no actions | Some actions (3–4) | 0.344 | −0.0841 | 1.410 | 0.919 |

| (re_plan = 2) | (0.252) | (0.329) | (0.355) | (0.303) | |

| Many actions (>4) | 0.557 ** | −0.0130 | 1.746 ** | 0.987 | |

| (re_plan = 3) | (0.251) | (0.330) | (0.439) | (0.326) | |

| Planned resource | Few actions (1–2) | 0.294 * | 0.777 *** | 1.342 * | 2.176 *** |

| Efficiency | (re_plan = 1) | (0.174) | (0.243) | (0.233) | (0.529) |

| Some or many actions (>2) | 0.0528 | 0.577 *** | 1.054 | 1.781 *** | |

| (re_plan = 2) | (0.140) | (0.217) | (0.147) | (0.386) | |

| Support measures | Financial incentives | 0.815 *** | 0.733 *** | 2.260 *** | 2.082 *** |

| (sup_fin = 1) | (0.104) | (0.138) | (0.235) | (0.288) | |

| Potential markets and custom. | 0.850 *** | 0.697 *** | 2.339 *** | 2.007 *** | |

| (sup_mark = 1) | (0.132) | (0.179) | (0.308) | (0.360) | |

| Technical support | 0.223 * | 0.594 *** | 1.250 * | 1.812 *** | |

| (sup_tech = 1) | (0.123) | (0.156) | (0.153) | (0.282) | |

| Marketing and distribution | 0.576 *** | 0.407 ** | 1.778 *** | 1.502 ** | |

| (sup_cons = 1) | (0.136) | (0.194) | (0.243) | (0.291) | |

| Green jobs (%) | >5% and ≤10% | 0.722 *** | 0.383 | 2.059 *** | 1.466 |

| (green_job = 10) | (0.226) | (0.296) | (0.466) | (0.434) | |

| >10% and ≤30% | 1.026 *** | 0.507 ** | 2.789 *** | 1.660 ** | |

| (green_job = 30) | (0.174) | (0.230) | (0.485) | (0.381) | |

| >30% and ≤100% | 1.295 *** | 0.329 ** | 3.650 *** | 1.389 ** | |

| (green_job = 100) | (0.117) | (0.164) | (0.427) | (0.228) | |

| Sector of activity | Retail (NACE-G) | 0.467 *** | 0.0392 | 1.595 *** | 1.040 |

| (nace = 1) | (0.114) | (0.157) | (0.182) | (0.163) | |

| Country | Italy | 0.206 | −0.312 | 1.229 | 0.732 |

| (base: ipscntry = Croatia) | (0.175) | (0.210) | (0.215) | (0.154) | |

| Hungary | −0.496 *** | −1.100 *** | 0.609 *** | 0.333 *** | |

| (0.174) | (0.212) | (0.106) | (0.0704) | ||

| Austria | 0.703 *** | −0.909 *** | 2.020 *** | 0.403 *** | |

| (0.172) | (0.247) | (0.348) | (0.0997) | ||

| Slovenia | 0.369 ** | −0.531 *** | 1.446 ** | 0.588 *** | |

| (0.158) | (0.193) | (0.228) | (0.114) | ||

| Does your company | sell only services | −0.190 * | −0.268 * | 0.827 * | 0.765 * |

| (serv = 1) | (0.109) | (0.148) | (0.0904) | (0.113) | |

| Selling products or | Yes | −0.165 | −0.187 | 0.847 | 0.830 |

| services to companies | (b2b = 1) | (0.117) | (0.155) | (0.0994) | (0.129) |

| Constant | −2.166 *** | −1.917 *** | 0.115 *** | 0.147 *** | |

| (0.293) | (0.373) | (0.0337) | (0.0548) | ||

| Observations | 2530 | 2530 | 2530 | 2530 | |

| LR chi2 (38) = 512.02 Pseudo R2 = 0.1146 | |||||

| Hypothesis | Acceptance |

|---|---|

| H1: Engagement in resource efficiency actions increases the likelihood of offering green products and services. | Partially accepted |

| H2: SMEs that express a support need are more likely to offer green products and services. | Accepted |

| H3: Increasing the green jobs ratio increases the likelihood of offering green products and services. | Accepted |

| H4: Offering only services affects the green product offering. | Accepted |

| H5: Selling products or services to businesses (B2B) is associated with a lower likelihood of offering green products and services. | Rejected |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alfirević, N.; Pavlinović Mršić, S.; Mlaker Kač, S. Multinomial Logistic Analysis of SMEs Offering Green Products and Services in the Alps–Adriatic Macroregion. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4721. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104721

Alfirević N, Pavlinović Mršić S, Mlaker Kač S. Multinomial Logistic Analysis of SMEs Offering Green Products and Services in the Alps–Adriatic Macroregion. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4721. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104721

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlfirević, Nikša, Slađana Pavlinović Mršić, and Sonja Mlaker Kač. 2025. "Multinomial Logistic Analysis of SMEs Offering Green Products and Services in the Alps–Adriatic Macroregion" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4721. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104721

APA StyleAlfirević, N., Pavlinović Mršić, S., & Mlaker Kač, S. (2025). Multinomial Logistic Analysis of SMEs Offering Green Products and Services in the Alps–Adriatic Macroregion. Sustainability, 17(10), 4721. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104721