Revitalizing Inner Areas Through Thematic Cultural Routes and Multifaceted Tourism Experiences

Abstract

1. Introduction

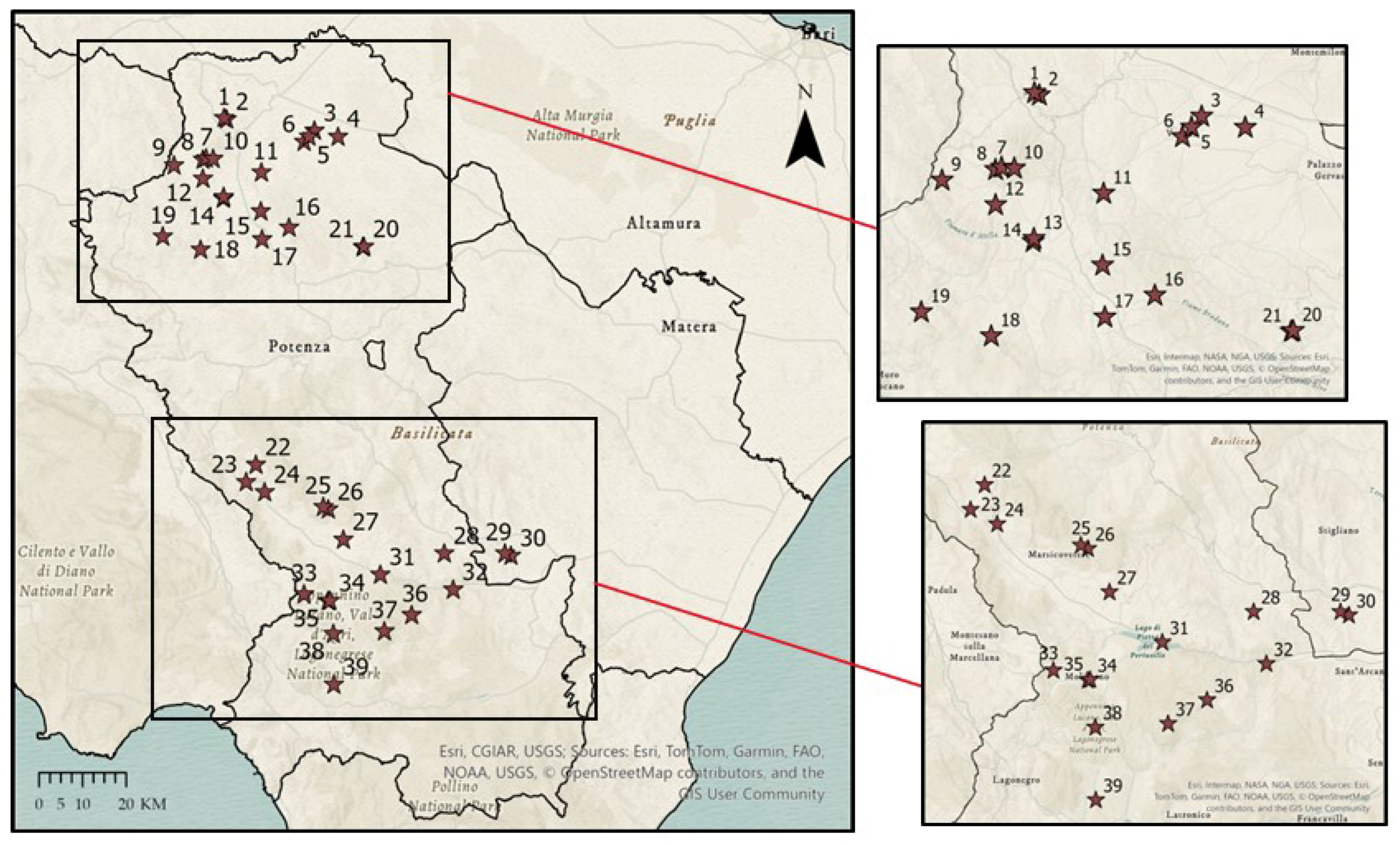

2. Study Area

3. Materials and Methods

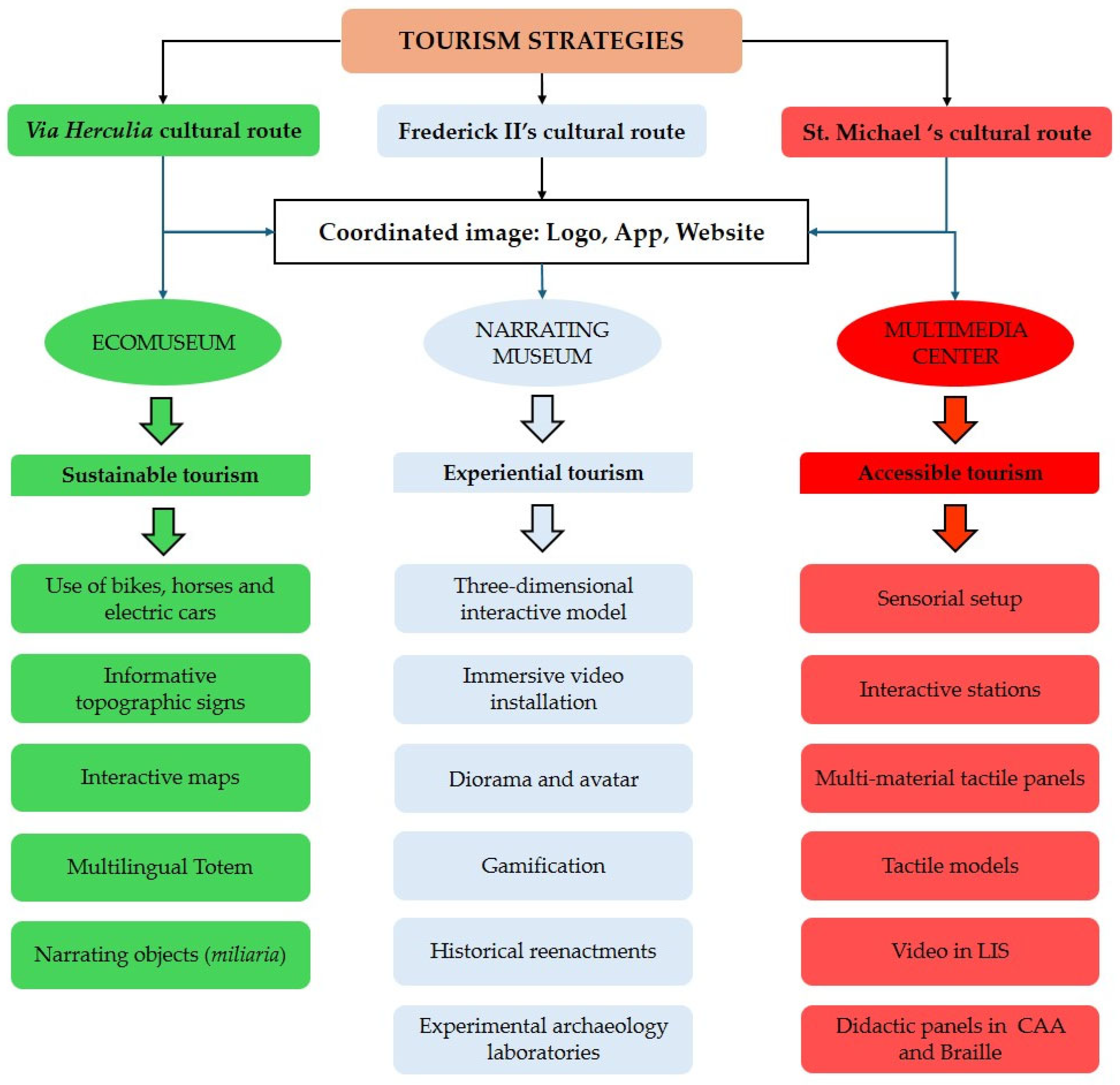

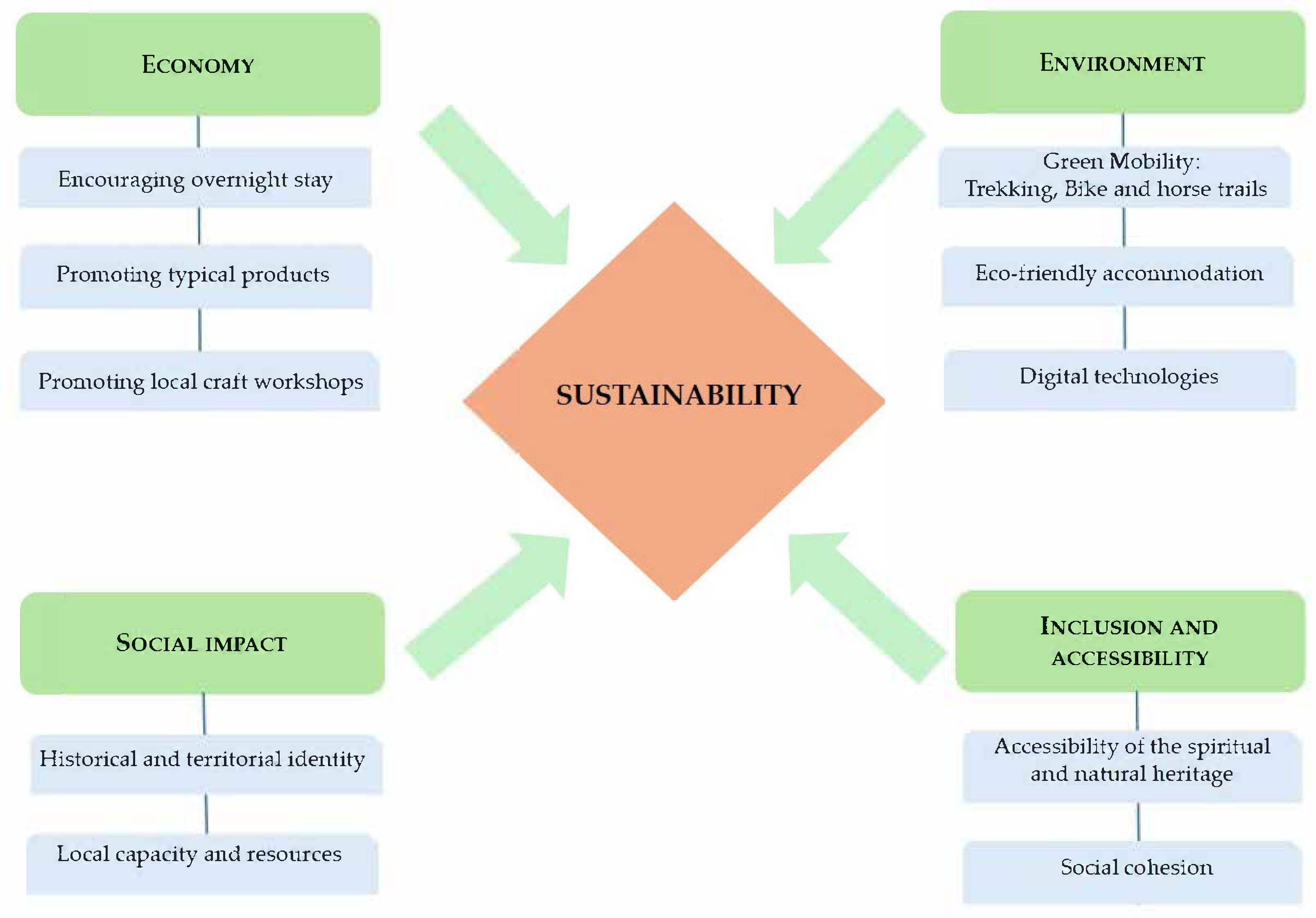

4. Results

4.1. Ancient Cultural Route: Via Herculia

4.2. Frederick II’s Cultural Route

4.3. St Michael’s Cultural Route

5. Discussion

6. Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

- (1)

- Economic constraints. The financial resources required to roll out the proposed enhancement activities may exceed the current budgetary capacity of local authorities. Nevertheless, municipalities could pool their resources and work together to reach the shared objective of improved accessibility and cultural engagement. A noteworthy example is the long-standing interest in the Via Herculia, as demonstrated by the “La Via delle Meraviglie” project, funded by the Ministry of Culture, which brings together 43 municipalities across Basilicata [205]. In addition, several low-cost or collaborative solutions could be carried out by sector-specific associations or even by students as part of educational or research initiatives. These might include mobile applications, interactive websites, 3D digital reconstructions, typhlo-didactic maps, and multimaterial informational panels. A crowd-sourcing approach could also be set up to gather contributions, ideas, and even microfunding from the wider community, enhancing both participation and innovation in project development.

- (2)

- Sample size limitations. A second major limitation is the lack of consistent data on the number of visitors to each cultural site included in the proposed itineraries. In many cases, the absence of systematic ticketing makes it difficult to track and break down visitor demographics. Such statistical data would have been instrumental in carrying out a detailed analysis of audience types and in drawing up personalized tourism solutions tailored to specific target groups. Implementing digital access systems or smart counters in the future could help to fill in these data gaps and support evidence-based planning.

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hibbert, C. The Grand Tour; Putnam: London, UK, 1969; ISBN 9780297178422. [Google Scholar]

- Feifer, M. Tourism in History. From Imperial Rome to Present; Stein and Day: New York, NY, USA, 1985; ISBN 100812830873. [Google Scholar]

- ECTARC. Contribution to the Drafting of a Charter for Cultural Tourism; European Centre for Traditional and Regional Cultures: Llangollen, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Dionyssopoulou, P.; Lagos, D.; Tsartas, P. European union policy framework on culture tourism. Tourism Today 2003, 3, 1–17. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322131408_European_Union_Policy_Framework_on_Cultural_Policy (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- UN Tourism. Manila Declaration on World Tourism; UN Tourism: Madrid, Spain, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- UN Tourism. The State’s Role in Protecting and Promoting Culture as a Factor of Tourism Development and the Proper Use and Exploitation of the National Cultural Heritage of Sites and Monuments for Tourism; UN Tourism: Madrid, Spain, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- WTO (World Tourism Organization). Definitions of Tourism; WTO (World Tourism Organization): Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, J. Motivations for pleasure vacation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1979, 6, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, R.W.; Goeldner, R. Tourism: Principals, Practices, Philosophies; Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1986; ISBN 978-0471015574. [Google Scholar]

- Bonink, C. Cultural Tourism Development and Government Policy: A Comparison of the United Kingdom and the Netherlands; University of Utrecht: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- GEATTE (Groupement D’etude et D’assistance Pour L’amenagement du Territoire, le Tourisme et L’environnement). Le Tourisme Culturel en Europe; DG XXIII; European Commission: Bruxelles, Belgium, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Martelloni, R. Il turismo culturale: Stato dell’arte, vincoli e opportunità. Econ. Cultura 2006, 4, 509–520. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Garibaldi, R. (Ed.) II Turismo Culturale Europeo. Prospettive Verso il 2010; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2012; ISBN 9788820418694. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G. (Ed.) Cultural Tourism in Europe; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 1996; ISBN 100851991041. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P.; Manente, M. Economia del Turismo. Modelli di Analisi e Misura delle Dimensioni Economiche del Turismo; Touring Editore: Milano, Italy, 2000; ISBN 9788836520916. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Benassi, F.; D’Elia, M.; Petrei, F. The “meso” dimension of territorial capital: Evidence from Italy. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2021, 13, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizzi, F.T.; Horta Ribeiro Antunes, I.M.; Marinho Reis, A.P.; Giano, S.I.; Masini, N.; Muceku, Y.; Pescatore, E.; Potenza, M.R.; Corbalán Andreu, C.; Sannazzaro, A.; et al. From settlement abandonment to valorisation and enjoyment strategies: Insights through EU (Portuguese, Italian) and non- EU (Albanian) ‘ghost towns’. Heritage 2024, 7, 3867–3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, L.; Petrei, F.; Santoro, M.T. Il Turismo Culturale in Italia. Analisi Territoriale Integrata dei Dati; Istituto Nazionale di Statistica: Roma, Italy, 2023; ISBN 9788880806004. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Garau, C.; Annunziata, A.; Yamu, C. The Multi-Method Tool ‘PAST’ for Evaluating Cultural Routes in Historical Cities: Evidence from Cagliari, Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominioni, S. Cultural Routes of the Council of Europe: A New Approach to Cultural Heritage and Cultural Tourism; European Tourism Day (Brussels, 16 December 2015), Institut Europeen des Itineraires Culturels, Brochure 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/14543/attachments/17/translations (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- The Council of Europe. European Cultural Convention—European CultureRoutes. 2001. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/cultural-routes (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Cultural Route of the Council of Europe. Available online: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/node/57321_en (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Council of Europe. Resolution CM/Res(2010)53. In Proceedings of the Enlarged Partial Agreement on Cultural Routes (Adopted by the Committee of Ministers at Its 1101st Meeting of the Ministers’ Deputies), 8 December 2010. Available online: https://www.cultura.gob.es/dam/jcr:676626cf-af41-4904-a04d-6725b1e4fa2b/resolution-cm-2010-53itinerarios-en.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Khovanova-Rubicondo, K. Cultural routes as a source for new kind of tourism development: Evidence from the council of Europe’s Programme. Int. J. Herit. Digit. Era 2012, 1, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Pilgrimage Routes. Available online: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/6edd47da29964389a4fbd99982bc4b5b (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Olsen, D.H.; Trono, A.; Fidgeon, P.R. Pilgrimage trails and routes: The journey from the past to the present. In Religious Pilgrimage Routes and Trails: Sustainable Development and Management; Trono, A., Olsen, D.H., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2018; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Trono, A. Cultural and Religious Routes: A New Opportunity for Regional Development. In New Tourism in the 21st Century: Culture, the City, Nature and Spirituality; Lois-González, R.C., Santos-Solla, X.M., González, R.C.L., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2014; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Oikonomopoulou, E.; Delegou, E.T.; Sayas, J.; Moropoulou, A. An innovative approach to the protection of cultural heritage: The case of cultural routes in Chios Island, Greece. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2017, 14, 742–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Via Romea Imperiale. Available online: https://www.viargimperiale.it (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Lin, X.; Shen, Z.; Teng, X.; Mao, O. Cultural Routes as Cultural Tourism Products for Heritage Conservation and Regional Development: A Systematic Review. Heritage 2024, 7, 2399–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The ICOMOS Charter on Cultural Routes. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters-and-doctrinal-texts/ (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- European Institute of Cultural Itineraries. Available online: https://www.coe.int/it/web/cultural-routes/european-institute-of-cultural-routes (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- ICOMOS. Goals of the International Scientific Committees. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/international-scientific-committees/ (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Ducassi, S.I.; Rosa, M. A New Category of Heritage for Understanding, Cooperation and Sustainable Development. Their Significance within the Macrostructure of Cultural Heritage. The Role of the CIIC of ICOMOS: Principles and Methodology. In Proceedings of the Scientific Symposium (ICOMOS General Assemblies)-15th ICOMOS General Assembly and International Symposium: ‘Monuments and Sites in Their Setting—Conserving Cultural Heritage in Changing Townscapes and Landscapes’, Xi’an, China, 17–21 October 2005. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. The ICOMOS Charter on Cultural Routes. In Proceedings of the 16th General Assembly of ICOMOS, Québec City, QC, Canada, 29 September–5 October 2008; Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/9-uncategorised/412-16th-general-assembly-of-icomos-quebec-2008 (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Murray, M.; Graham, B. Exploring the dialectics of route-based tourism: The Camino de Santiago. Tour. Manag. 1997, 18, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granero Gallegos, A.; Ruiz Juan, F.; Garcia Montes, M.E. Study about motivations to go through the Way of Saint James. Apunt. Educ. Fis. Deportes 2007, 89, 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Ramírez, J. The roads of the heritage. Tourist routes and cultural itineraries. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2011, 9, 225–236. [Google Scholar]

- Dayoub, B.; Yang, P.; Dayoub, A.; Omran, S.; Li, H. The role of cultural routes in sustainable tourism development: A case study of Syria’s spiritual route. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2020, 15, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdrali, D.; Chazapi, K. Cultural tourism in a greek insular community: The residents’ perspective. Tourismos 2007, 2, 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bitsani, E.; Aliki, E. The management of Natural World Heritage sites as an essential component of cultural tourism and sustainable development the tokaj-hollókö case study in northeastern Hungary: From a national/local past towards an international/global future. In Handbook on Tourism Development and Management; Collins, K.H., Ed.; NOVA Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 127–163. [Google Scholar]

- Brebbia, C.A.; Doganer, S.; Dupont, W.; Doganer, S.; Dupont, W. Accelerating cultural heritage tourism in San Antonio: A community-based tourism development proposal for the missions historic district. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2015, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Vasile, V.; Bănică, E. Cultural Heritage Tourism Export and Local Development. Performance Indicators and Policy Challenges for Romania. In Caring and Sharing: The Cultural Heritage Environment as an Agent for Change; Vasile, V., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 271–290. [Google Scholar]

- Cirianni, F.M.M.; Leonardi, G.; Luongo, A.S. Strategies and Measures for a Sustainable Accessibility and Effective Transport Services in Inner and Marginal Areas: The Italian Experience. In New Metropolitan Perspectives. NMP 2022. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Calabrò, F., Della Spina, L., Piñeira Mantiñán, M.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham. Switzerland, 2022; Volume 482, pp. 363–376. [Google Scholar]

- Ottomano Palmisano, G.; Sardaro, R.; La Sala, P. Recovery and Resilience of the Inner Areas: Identifying Collective Policy Actions through PROMETHEE II. Land 2022, 11, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, F.; Casavola, P.; Lucatelli, S. A Strategy for Inner Areas in Italy: Definition, Objectives; Tools and Governance: Roma, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- National Strategy for Internal Areas. Available online: https://www.agenziacoesione.gov.it/strategia-nazionale-aree-interne/ (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Vitale, C. La valorizzazione del patrimonio culturale nelle Aree Interne. Considerazioni preliminari. Aedon 2018, 3. ISSN 1127-1345. Available online: https://aedon.mulino.it/archivio/2018/3/vitale.htm (accessed on 12 February 2025). (In Italian).

- Mastrangioli, A.; Brandano, M.G. Italian inner areas as tourist destinations: A cluster analysis of the pilot areas. Sci. Reg. 2021, 20, 519–540. [Google Scholar]

- Mantegazzi, D.; Pezzi, M.G.; Punziano, G. Tourism Planning and Tourism Development in the Italian Inner Areas: Assessing Coherence in Policy-Making Strategies. In Regional Science Perspectives on Tourism and Hospitality; Ferrante, M., Fritz, O., Öner, Ö., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 447–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, M.M. Cultural routes—From cultural to creative tourism. In Creating and Managing Experiences in Cultural Tourism; Jelinčić, D.A., Mansfeld, Y., Eds.; World Scientific: Singapore, 2019; pp. 155–170. [Google Scholar]

- Escudero Gómez, L.A. A Perspective for High-Quality Urban Cultural Tourism and the End of Mass Cultural Tourism. In Cultural Tourism: Perspectives, Opportunities and Challenges; Korstanje, M., Catenazzo, G., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Dattilo, B.; Petrei, F. Turismo e cultura: Definizioni e perimetro per una loro misurazione. In Il Turismo Culturale in Italia. Analisi Territoriale Integrata dei Dati; Cavallo, L., Petrei, F., Santoro, M.T., Eds.; Istituto Nazionale di Statistica: Roma, Italy, 2023; pp. 11–19. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Gizzi, F.T.; Proto, M.; Potenza, M.R. The Basilicata region (Southern Italy): A natural and ‘human-built’ open-air laboratory for manifold studies. Research trends over the last 24 years (1994–2017). Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2019, 10, 433–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogliani, F. Raccontare l’archeologia in Basilicata: Alcuni progetti di valorizzazione e di musealizzazione del territorio (Progetto Archeo-Bradano PIT Bradanica; Progetto Satrianum). Forma Urbis 2018, XXIII, 47–56. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Masini, N.; Gizzi, F.T.; Biscione, M.; Fundone, V.; Sedile, M.; Sileo, M.; Pecci, A.; Lacovara, B.; Lasaponara, R. Medieval archaeology under the canopy with LiDAR. The (re)discovery of a medieval fortified settlement in Southern Italy. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masini, N.; Abate, N.; Gizzi, F.T.; Vitale, V.; Minervino Amodio, A.; Sileo, M.; Biscione, M.; Lasaponara, R.; Bentivenga, M.; Cavalcante, F. UAV LiDAR Based Approach for the Detection and Interpretation of Archaeological Micro Topography under Canopy—The Rediscovery of Perticara (Basilicata, Italy). Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofoli, G. Lo sviluppo locale: Modelli teorici e comparazioni internazionali. Meridiana 1999, 34–35, 71–96. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Butowki, L. Tourism as a development factor in the light of regional development theories. Turyzm/Tourism 2010, 20, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujadinović, S.; Šabić, D.; Gajić, M.; Golić, R.; Kazmina, L.; Joksimović, M.; Krstić, F.; Malinić, V.; Sedlak, M. Tourism in the context of contemporary theories of regional development. J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijic SASA 2023, 73, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italian National Statistical Institute (Population as of 1 January 2024). Available online: http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?QueryId=18564 (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Treccani. Available online: https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/basilicata/ (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- UNESCO Geoparks. Available online: https://www.unesco.it/it/iniziative-dellunesco/geoparchi-2/ (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Environmental Protection Carabinieri. Available online: https://www.carabinieri.it/chi-siamo/oggi/organizzazione/tutela-forestale-ambientale-e-agroalimentare/comando-tutela-biodiversita’-e-parchi/utcb-e-le-130-riserve-naturali (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Basilicata Region: Protected Areas and Parks. Available online: https://www.parks.it/regione.basilicata/Eindex.php (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Seismic Zone Classification. Available online: http://zonesismiche.mi.ingv.it/class2004.html (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Guidoboni, E.; Ferrari, G.; Mariotti, D.; Comastri, A.; Tarabusi, G.; Sgattoni, G.; Valensise, G. CFTI5Med, Catalogo dei Forti Terremoti in Italia (461 a.C.-1997) e nell’area Mediterranea (760 a.C.-1500); Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV): Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizzi, F.T.; Potenza, M.R.; Zotta, C. 23 November 1980 Irpinia–Basilicata earthquake (Southern Italy): Towards a full knowledge of the seismic effects. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2012, 10, 1109–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legambiente. Available online: https://www.changeclimatechange.it/azioni/nemici/giaicmento-eni-val-dagri-1/#:~:text=In%20Val%20D’Agri%20%C3%A8,della%20produzione%20Eni%20in%20Italia (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Panorama Magazine. Available online: https://www.panorama.it/economia/basilicata-petrolio-e-manifattura-nella-piccola-grande-regione-del-sud (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Matera 2019. European Capital of Culture. Available online: https://www.matera-basilicata2019.it/it/ (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Matera 2019. European Capital of Culture. Available online: https://www.matera-basilicata2019.it/images/valutazioni/2_Impatto_economico_Matera2019_ITA.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Burrato, P. Il terremoto del 16 dicembre 1857: Geologia e geomorfologia dell’area epicentrale e identificazione della sorgente sismogenetica. In Viaggio Nelle Aree del Terremoto del 16 Dicembre 1857. L’opera di Robert Mallet nel Contesto Scientifico e Ambientale Attuale del Vallo di Diano e della Val d’Agri; Ferrari, G., Ed.; SGA: Bologna, Italy, 2004; Volume 1, pp. 187–208. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Gizzi, F.T.; Masini, N. Damage scenario of the earthquake on 23 July 1930 in Melfi: The contribution of technical documentation. Ann. Geophys. 2004, 47, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrì, N. La Fruibilità dei Beni Culturali. Bollettino Sezione Campania Associazione Nazionale Insegnanti Storia Naturale, 2002, n. 24, Sezione scientifica: Relazioni dei Coordinatori dei Gruppi di Studio, pp. 119–125. (In Italian)

- Cetorelli, G.; Papi, L. (Eds.) Manuale di Progettazione per L’accessibilità e la Fruizione Ampliata del Patrimonio Culturale. Dai Funzionamenti della Persona ai Funzionamenti dei Luoghi della Cultura; CNR Edizioni: Roma, Italy, 2024; ISBN 978-8880806103. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Polverini, L. Le regioni nell’Italia romana. Geogr. Antiq. 1988, VII, 23–33. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Del Lungo, S. Topografia e antichità della via Herculia in Basilicata, tra leggenda e realtà. In Lungo la Via Herculia. Storia, Territorio, Sapori; Sabia, C.A., Sileo, R., Eds.; Zaccara: Lagonegro, Italy, 2013; pp. 15–80. ISBN 9788895508528. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Del Lungo, S. (Ed.) Antiche vie in Basilicata. Percorsi, Ipotesi, Osservazioni, Note e Curiosità; Istituto Geografico Militare: Firenze, Italy, 2019; ISBN 978-8852391019. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.; Del Lungo, S.; Sannazzaro, A.; Lazzari, M. Geological and Geomorphological Controls on the Path of an Intermountain Roman Road: The Case of the Via Herculia, Southern Italy. Geosciences 2019, 9, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelin Routes and Maps. Available online: https://www.viamichelin.it/ (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Museums and Archaeological Parks of Venosa and Melfi. Available online: https://artsupp.com/en/venosa/museums/area-archeologica-di-venosa (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Salvatore, M.R. (Ed.) Venosa: Un Parco Archeologico e un Museo. Come e Perché, Catalogo della Mostra; Scorpione: Taranto, Italy, 1984. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- De Lachenal, L. L’Incompiuta di Venosa. Un’abbaziale fra propaganda e reimpiego. Mélanges L’École Française Rome 1998, 110–111, 299–315. (In Italian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucignano, M. Comunicare l’assenza. L’Incompiuta di Venosa tra Conservazione e Innovazione; TRIA Urban Studies 4; Federico II University Press: Napoli, Italy, 2021; ISBN 9788868870959. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Nava, M.L.; Cracolici, V.; Fletcher, R. La romanizzazione della Basilicata nord-orientale tra Repubblica e Impero. In Proceedings of the 25° Convegno Nazionale Sulla Preistoria, Protostoria e Storia della Daunia, San Severo, Italy, 3–5 December 2004; Centro Grafico S.r.l: San Severo, Italy, 2005; pp. 209–220. (In Italian). [Google Scholar]

- Sannazzaro, A. Un segmento della via Herculia tra archeologia e storia. In Lungo la via Herculia. Storia, Territorio, Sapori; Sabia, C.A., Sileo, R., Eds.; Zaccara: Lagonegro, Italy, 2013; pp. 119–140. ISBN 9788895508528. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Sannazzaro, A. Progettare una strada: Il contesto insediativo ed epigrafico. I casi di studio di Potentia e Nerulum. In Antiche vie in Basilicata. Percorsi, Ipotesi, Osservazioni, Note e Curiosità; Del Lungo, S., Ed.; Istituto Geografico Militare (IGM): Firenze, Italy, 2019; pp. 123–139. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Donnici, F. Testimonianze pavimentali da Potentia e dal suo ager suburbanus. Boll. Online dell’Associazione Ital. Studio Conserv. Mosaico 2017, 1, 1–19. Available online: http://www.aiscom.it/bollettino/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/11/DonniciPotentia_CONTRIBUTI_1_2017.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2024). (In Italian).

- Capano, A. (Ed.) Beni Culturali di Potenza; Soprintendenza Archeologica della Basilicata/C.G.M. S.r.l.: Agropoli, Italy, 1989. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Di Noia, A. Potentia. La Città Romana tra età Repubblicana e Tardo Antica; I Quaderni del Consiglio Regionale della Basilicata: Melfi, Italy, 2008. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Greco, R.; Sannazzaro, A. Museo Basilicata. Itinerari Archeologici per Piccoli Viaggiatori; Carocci Editore: Roma, Italy, 2022; ISBN 9788829012701. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Greco, R.; Sannazzaro, A. (Eds.) Potentia. Dall’archeologia allo Storytelling; Hermaion Edizioni: Potenza, Italy, 2024; ISBN 9791280996398. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Russo, A.; Gargano, M.P.; Di Giuseppe, H. Dalla villa dei Bruttii Praesentes alla proprietà imperiale. Il complesso archeologico di Marsicovetere-Barricelle (PZ). Siris 2007, 8, 81–114. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Mucciarelli, M.; Bianca, M.; Liberatore, D.; Iaria, M. Analisi delle possibili cause di crollo di una villa romana in Alta Val d’Agri, Appendix to the article of Russo, A.; Gargano, M.P.; Di Giuseppe, H. Dalla villa dei Bruttii Praesentes alla proprietà imperiale. Il complesso archeologico di Marsicovetere—Barricelle (PZ). Siris 2007, 8, 114–119. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Regional Direction of National Museums of Basilicata. Available online: https://artsupp.com/en/matera/institutions/direzione-regionale-musei-basilicata (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Giardino, L. Grumento Nova. In Bibliografia Topografica della Colonizzazione Greca in Italia e Nelle Isole Tirreniche; Ecole Francaise de Rome: Rome, Italy, 1990; Volume VIII, pp. 204–211. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Mastrocinque, A. Grumentum Romana; Valentina Porfidio Editore: Moliterno, Italy, 2009. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Bottini, P. (Ed.) Il Museo Archeologico Nazionale Dell’alta Val d’Agri; Ministero Beni Culturali e Ambientali/Alfagrafica Volonnino: Lavello, Italy, 1997. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Busino, N. L’alta valle del Cervaro fra tarda antichità e alto Medioevo: Dati preliminari per una ricerca topografica. In La Campania fra Tarda Antichità e Alto Medioevo. Ricerche di Archeologia del Territorio; Ebanista, C., Rotili, M., Eds.; Atti della Giornata di studio (Cimitile, 10 giugno 2008); Tavolario Editore: Cimitile, Italy, 2009; pp. 129–152. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, C.D. Federico II e l’Italia. Percorsi, Luoghi, Segni e Strumenti, Catalogo della Mostra (Roma 1995–1996); De Luca Editori: Roma, Italy, 1995; ISBN 888016130X. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, C.D. (Ed.) “Castra ipsa possunt et debent reparari”. Indagini conoscitive e metodologie di restauro delle strutture castellane normanno-sveve. In Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studio, Castello di Lagopesole, 16–19 October 1997; Edizioni De Luca: Roma, Italy, 1998; ISBN 8842056707. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Masini, N. Dai Normanni agli Angioini: Castelli e fortificazioni della Basilicata. In Storia della Basilicata. Il Medioevo; Fonseca, C.D., Ed.; Laterza: Roma-Bari, Italy, 2006; pp. 689–753. ISBN 9788858146576. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Murro, M. Il Castello di Federico: Note Storico-Architettoniche Sulla Residenza di Lagopesole in Basilicata; Atena Edizioni: Arma di Taggia, Italy, 1987; ISBN 9788867173709. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Rescio, P. Archeologia e Storia dei Castelli di Basilicata e Puglia; Rubbettino Editore: Soveria Mannelli, Italy, 1999; ISBN 9788872847800. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Rescio, P. Basilicata Terra di Castelli; Istituto Banco di Napoli: Napoli, Italy, 2004; EAN 2570251954547. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Lancieri, A. Il castello di Melfi. Arch. Stor. Calabr. Lucania 1962, 31, 207–214. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Levita, M. Il Castello di Melfi: Storia e Architettura; Mario Adda Editore: Bari, Italy, 2008. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Danieli, S.; Fortini, G.; Tardioli, F. Le Costituzioni di Melfi di Federico II: In Appendice: Testo Integrale delle Costituzioni Tradotte da Gemma Fortini; Nuovi Autori: Roma, Italy, 1985. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Guarini, G.B.S. Margherita: Cappella vulturina del ‘200. Napoli Nobilissima 1899, VIII, 113–118, 128–142. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Galli, E. La chiesa rupestre di S. Margherita. Arte Restauro 1940, XVII, 13–22. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Vivarelli, P. Pittura rupestre nell’Alta Basilicata. La Chiesa di S. Margherita a Melfi. Mélanges L’Ecole Française Roma Moyen Age Temps Modernes 1973, 85-2, 547–585. (In Italian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bologna, F. I Pittori alla Corte Angioina di Napoli—1266-1414 e un Riesame Dell’arte Nell’età Fridericiana; Ugo Bozzi Editore: Napoli, Italy, 1970; ISBN 271001178. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Leone, G. Palazzo San Gervasio e il Suo Castello; Schena Editore: Fasano, Italy, 1985; ISBN 9788875140601. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Garzia, T.; Deanna Vernetti, P.; Rosa, A. Testimonianze Federiciane in Basilicata: La Domus di Palazzo San Gervasio, il Palazzo Ducale di Lavello, il Castello di Monteserico: Catalogo della Mostra; Soprintendenza per i Beni Architettonici e per il Paesaggio della Basilicata: Potenza, Italy, 2007. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Ungolo, G. La Chiesa di San Gervasio al Palazzo: Santi, Chiese, Ville e Castelli alle Origini della Cittadina di Palazzo San Gervasio Lungo la via Appia Antica; Osanna Edizioni: Venosa, Italy, 2021; ISBN 108881676079. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- De Vita, R. Castelli, Torri ed Opere Fortificate di Puglia; Mario Adda Editore: Bari, Italy, 1974; ISBN 9788880820345. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Licinio, R. Castelli Medievali. Puglia e Basilicata dai Normanni a Federico II e Carlo d’Angiò; Edizioni Dedalo: Bari, Italy, 1994; ISBN 9788822061621. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, C.D. (Ed.) Itinerari Federiciani in Puglia. Viaggio nei Castelli e Nelle Dimore di Federico II di Svevia; Mario Adda Editore: Bari, Italy, 1997; ISBN 108880826093. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Mola, S. Puglia. I Castelli; Mario Adda Editore: Bari, Italy, 2005; ISBN 978-8880825623. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- In the Footsteps of Saint Michael. Available online: https://www.sulleormedisanmichele.it/origini-del-culto/ (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Sannazzaro, A. La Stipe Votiva di Monticchio Bagni (Rionero in Vulture, Italia). Natura e Sacro sul Monte Vulture nel Contesto Italico; YLA n. 3—BAR International Series 3049; BAR Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2021; ISBN 9781407358604. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Telesca, L. Culto e insediamenti micaelici in Basilicata. Theol. Viat. 1998, 3, 13–82. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Telesca, L. I santuari micaelici lucani, in Itinerari del sacro in terra lucana. Basilicata Reg. Not. 1999, 2, 159–162. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Catenacci, G. Il Vulture e la Badia di Monticchio; Laurenziana: Napoli, Italy, 1966; ISBN 9788881673360. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Pietrafesa, F. La Badia di Monticchio: Breve Storia; Laurenziana: Napoli, Italy, 1980. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Fortunato, G. La Badia di Monticchio; Osanna Edizioni: Venosa, Italy, 1985; ISBN 978881673360. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Del Lungo, S. La Memoria non scritta o non dichiarata: Il Vulture nella teoria e nel metodo sulla traditio dei disastri naturali. In Dalle Fonti All’evento; Gizzi, F.T., Masini, N., Eds.; Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane: Napoli, Italy, 2010; pp. 69–92. [Google Scholar]

- Telemaco Editions. Available online: https://www.telemacoedizioni.it/2012/11/la-chiesa-rupestre-di-san-michele-arcangelo-ad-acerenza-angelo-schiavone/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Ferretti, V. Pignola in tre Itinerari: Guida Turistica Ragionata; Centro Grafico Rocco Castrignano: Anzi, Italy, 1991. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Fanelli, P. Pignola: Il Patrimonio D’arte delle sue Chiese; Centro Grafico Rocco Castrignano: Anzi, Italy, 2008; ISBN 8889970146. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- General Catalog of Cultural Heritage—Italian Ministry of Culture. Available online: https://catalogo.beniculturali.it/detail/HistoricOrArtisticProperty/1700125255 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Pasquariello, G. Marsico Antica e Medievale; Finiguerra: Lavello, Italy, 2004. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Setari, E.; Verrascina, R. L’abbazia di Sant’Angelo al Monte Raparo. Basilicata Reg. Not. 1997, 2, 87–90. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Pertosa Caves. Available online: https://www.grottedipertosa.it/le-grotte (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- National Geographic. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/sacred-caves (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Carletti, C.; Otranto, G. Il Santuario di San Michele Arcangelo sul Gargano dalle Origini al X Secolo; Edipuglia: Bari, Italy, 1990. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Belli D’Elia, P. (Ed.) L’angelo, la Montagna, il Pellegrino: Monte Sant’Angelo e il Santuario di San Michele del Gargano: Archeologia, arte, Culto, Devozione dalle Origini ai Nostri Giorni; Grenzi Editore: Foggia, Italy, 1999; ISBN 9788872280584. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Del Lungo, S.; Lazzari, M.; Sabia, C. Il Sentiero del Culto tra i Luoghi Attraverso i Secoli; Zaccara: Lagonegro, Italy, 2013; ISBN 978889550829. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Sannazzaro, A.; Del Lungo, S. Paesaggio tra Archeologia e Ambiente: L’integrazione della componente culturale nelle schede della Rete Natura 2000 Basilicata. In Cultural Landscapes. Metodi, Strumenti e Analisi del Paesaggio fra Archeologia, Geologia e Storia in Contesti di Studio del Lazio e Della Basilicata (Italia); Gabrielli, G., Lazzari, M., Sabia, C.A., Del Lungo, S., Eds.; BAR International Series 2629; BAR Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 235–264. [Google Scholar]

- Del Lungo, S. Grumentinae Vites et Vina: Biodiversità Viticola, Cultura e Storia Nell’alta Val d’Agri; Dibuono Edizioni: Villa d’Agri, Italy, 2020; ISBN 9788899590475. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Giano, S.I.; Pescatore, E.; Biscione, M.; Masini, N.; Bentivenga, M. Geo- and Archaeo-heritage in the Mount Vulture Area: List, Data Management, Communication, and Dissemination. A Preliminary note. Geoheritage 2021, 14, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Lungo, S. (Ed.) Fra le Montagne di Enotria. Forma Antica del Territorio e Paesaggio Viticolo in Alta Val d’Agri; L’Universo, Istituto Geografico Militare: Firenze, Italy, 2022; ISSN 00420409. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Uriely, N.; Israeli, A.A.; Reichel, A. Heritage proximity and resident attitudes toward tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 859–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.S.; Azreena Mubin, S. Interactive Multimedia for Promoting Cultural Heritage Tourism in Penang. In Proceedings of the Informatics and Technology Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1–2 November 2022; pp. 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Garau, C. Emerging technologies and cultural tourism: Opportunities for a cultural urban tourism research agenda. In Tourism in the City: Towards an Integrative Agenda on Urban Tourism; Bellini, N., Pasquinelli, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamhawi, M.M.; Hajahjah, Z.A. It-innovation and technologies transfer to heritage sites: The case of madaba, Jordan. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 2016, 16, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Nag, A.; Mishra, S. Sustainable Competitive Advantage in Heritage Tourism: Leveraging Cultural Legacy in a Data-Driven World. In Review of Technologies and Disruptive Business Strategies (Review of Management Literature; Singh Kaurav, R.P., Mishra, V., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2024; Volume 3, pp. 137–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafa, M.N. Achilles as a Marketing Tool for Virtual Heritage Applications. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2017, 11, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L. Design of Virtual Cultural Tourism Platform Based on Concept of Metauniverse. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Social Sciences and Intelligence Management (SSIM), Taichung, Taiwan, 15–17 December 2023; pp. 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strategic Tourism Plan 2023-2027-Italian Ministry of Tourism. Available online: https://politichecoesione.governo.it/it/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Visitors Museums Monuments and State Archaeological Areas—YEAR 2023—Italian Ministry of Culture. Available online: https://statistica.cultura.gov.it/storico2/rilevazioni/musei/anno%202023/musei_tavola7_2023.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Effenove, S.r.l.s. Available online: https://www.effenove.it/works/museo-di-venosa/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- App “Potenza Celata”. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=it.ghs.aritage.app (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Sabia, C.A.; Sileo, R. (Eds.) Lungo la Via Herculia. Storia, Territorio, Sapori; Zaccara: Lagonegro, Italy, 2013; ISBN 9788895508528. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Appennino Coast to Coast. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0nA9WdnMDQI (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Fafouti, A.E.; Vythoulka, A.; Delegou, E.T.; Farmakidis, N.; Ioannou, M.; Perellis, K.; Giannikouris, A.; Kampanis, N.A.; Alexandrakis, G.; Moropoulou, A. Designing Cultural Routes as a Tool of Responsible Tourism and Sustainable Local Development in Isolated and Less Developed Islands: The Case of Symi Island in Greece. Land 2023, 12, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, M. Ecomusei: Guida Europea; Allemandi Editore: Torino, Italy, 2002; ISBN 9788842211167. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Riva, R. (Ed.) Ecomuseums and Cultural Landscapes. State of the Art and Future Prospects; Maggioli Editore: Santarcangelo di Romagna, Italy, 2017; ISBN 9788891624956. [Google Scholar]

- Guido, H.F. UNESCO Regional Seminar: Round Table on the Development and the Role of Museums in the Contemporary World. UNESCO document 1973, SHC.72/CONF.28/4 (Santiago de Chile, Chile 20-31 May 1972). Available online: https://www.ces.uc.pt/projectos/somus/docs/Santiago%20declaration%201972.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Davis, P. Ecomuseums and the democratization of cultural tourism. Tour. Cult. Commun. 2004, 5, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Carretero, C. Significance and social value of cultural heritage: Analyzing the fractures of heritage. In Science and Technology for the Conservation of Cultural Heritage; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; pp. 387–392. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, P. The Eco-museum: Innovation that Risks the Future. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2002, 8, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P. New Museologies and the Ecomuseum. In The Ashgate Research Reader in Heritage and Identity; Grahamand, B., Howard, P., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing: Aldershot, UK, 2008; pp. 397–414. [Google Scholar]

- Burgers, G.J.; Napolitano, C.; Ricci, I. Ecomuseo della Via Appia: Un progetto di sviluppo sostenibile per la piana di Brindisi. In Territori e Comunità. Le Sfide Dell’autogoverno Comunitario. Atti dei Laboratori del VI Convegno della Società dei Territorialisti, Castel del Monte (BA), 15–17 November 2018; Gisotti, M.R., Rossi, M., Eds.; SdT Edizioni: Bologna, Italy, 2020; pp. 37–45. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Gizzi, F.T.; Biscione, M.; Danese, M.; Maggio, A.; Pecci, A.; Sileo, M.; Potenza, M.R.; Masini, N.; Ruggeri, A.; Sileo, A.; et al. Students Meet Cultural Heritage: An Experience within the Framework of the Italian School-Work Alternation (SWA)—From Outcomes to Outlooks. Heritage 2019, 2, 1986–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission-Innovation in Territories. Available online: http://s3platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/documents/20182/225192/IT_Basilicata_RIS3_201508_Final.pdf/c70a3f9e-ea3d-4717-a7f6-16919e047f79 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Colletta, T.; Niglio, O. Per un Turismo Culturale Qualificato Nelle Città Storiche. La Segnaletica Urbana e L’innovazione Tecnologica; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2016; ISBN 9788891742797. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Basilicata Turistica. Available online: https://www.basilicataturistica.it/scopri-la-basilicata/arte-e-cultura-in-basilicata/musei-in-basilicata/musei-multimediali-in-basilicata/il-mondo-di-federico-ii-castellagopesole/ (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Restoration and recovery work—Palatium Regium. Sannazzaro, A. (Institute of Heritage Science, Tito, Potenza, Italy); Clinco, A. (Comune di Palazzo San Gervasio, Basilicata, Potenza, Italy). Personal communication, 7 February 2025.

- Serrat, O. Storytelling. In Knowledge Solutions; Springer: Singapore, 2017; ISBN 9789811009839. [Google Scholar]

- Corallo, A.; Esposito, M.; Marra, M.; Pascarelli, C. Transmedia digital storytelling for cultural heritage visiting enhanced experience. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality and Computer Graphics, Santa Maria al Bagno, Italy, 24–27 June 2019; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Petousi, D.; Katifori, A.; Servi, K.; Roussou, M.; Ioannidis, Y. Interactive Digital Storytelling in Cultural Heritage: The Transformative Role of Agency. In Interactive Storytelling. ICIDS 2022; Vosmeer, M., Holloway-Attaway, L., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 13762. [Google Scholar]

- Kasemsarn, K.; Harrison, D.; Nickpour, F. Applying Inclusive Design and Digital Storytelling to Facilitate Cultural Tourism: A Review and Initial Framework. Heritage 2023, 6, 1411–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colucci Cante, L.; Di Martino, B.; Graziano, M.; Branco, D.; Pezzullo, G.J. Automated Storytelling Technologies for Cultural Heritage. In Advances in Internet, Data & Web Technologies; Barolli, L., Ed.; EIDWT 2024. Lecture Notes on Data Engineering and Communications Technologies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 193. [Google Scholar]

- Galán-Pérez, F.J.; Biedermann, A. Joint development of video mapping contents on the industrial and cultural heritage of Zaragoza (Spain). In Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 632–638. [Google Scholar]

- Cisternino, D.; Corchia, L.; De Luca, V.; Gatto, C.; Liaci, S.; Scrivano, L.; Trono, A.; De Paolis, L.T. Augmented Reality Applications to Support the Promotion of Cultural Heritage. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2021, 14, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Hao, F. Metaverse and regenerative tourism: The role of avatars in promoting sustainable practices. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 29, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.P.; Frade, D.; Dias, D.R.C.; Almeida, M.A. Gamification and Tourism: The experience of built cultural heritage mediated by digital technology. In Proceedings of the 26th Symposium on Virtual and Augmented Reality, Manaus, Brazil, 30 September–3 October 2024; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 279–283. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; Yao, Z.; Zeng, Z.; He, Y. Co-creation Cultural Tourism Game Design Based on Scene Theory, Lecture Notes in Computer Science. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, HCII 2024, Washington, DC, USA, 29 June 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 15378 LNCS, pp. 309–322. [Google Scholar]

- Yolthasart, S.; Intawong, K.; Thongthip, P.; Puritat, K. The Game of Heritage: Enhancing Virtual Museum Visits Through Gamification for Tourists. TEM J. Open Access 2024, 13, 3359–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Available online: https://www.unesco.it/it/iniziative-dellunesco/patrimonio-culturale-immateriale/falconeria/ (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Mathieu, J.R. (Ed.) Experimental Archaeology. Replicating Past Objects, Behaviours and Processes; Bar International Series; BAR Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2002; ISBN 9781841714158. [Google Scholar]

- Gaj, G. Archeologia Sperimentale. Technologhia 2004, I, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Gaj, G. Archeologia Sperimentale. In Metodi e Pratica della Cultura Materiale. Produzione e Consumo dei Manufatti; Giannichedda, E., Ed.; Istituto Internazionale di Studi Liguri: Bordighera, Italy, 2004; pp. 19–24. ISBN 9788886796118. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Gaj, G.; Maestro, O. Archeologia Sperimentale: Un approccio sistematico alla disciplina. Archeol. Sperimentali. Temi Metod. Ric. 2023, 04, 8–20. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Carnegie, E.; McCabe, S. Re-enactment Events and Tourism: Meaning, Authenticity and Identity. Curr. Issues Tour. 2008, 11, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanhill, S.; Jansen-Verbeke, M. Cultural events as catalysts of change: Evidence from four European case studies. In Cultural Resources for Tourism: Patterns, Processes and Policies; Jansen-Verbeke, M., Priestley, G.K., Russo, A.P., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 155–181. [Google Scholar]

- Spicciarelli, R. Il Museo di Storia Naturale del Vulture Nell’Abbazia di San Michele Arcangelo a Monticchio; Grafie: Potenza, Italy, 2014. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Achillas, C.; Aidonis, D.; Tsampoulatidis, I.; Folinas, D.; Kostavelis, I.; Tsolakis, N.; Triantafyllou, D.; Vlachokostas, C.; Kelemis, A.; Dimou, V. Empowering Tourism Accessibility: A Digital Revolution in Pieria, Greece. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elangovan, N.; Sreedhara, R.; Chennattuserry, J.C.; Varghese, B. Harnessing digital innovation for inclusive tourism: Role of emerging technologies in creating accessibility and equity. In Inclusive Business Approaches in Tourism: Stakeholder Engagement; Korstanje, M.E., Chennattuserry, J.C., Elangovan, N., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ciaccheri, M.C. Musei e Accessibilità. Progettare L’esperienza e le Strategie; Editrice Bibliografica: Milano, Italy, 2024; ISBN 9788893576352. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Cetorelli, G.; Guido, M.R. Accessibilità e Patrimonio Culturale. Linee Guida al Piano Strategico-Operativo, Buone Pratiche e Indagine Conoscitiva; Quaderni della valorizzazione, NS 7; Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali e per il Turismo: Roma, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://www.museoomero.it/notizie/accessibilita-e-patrimonio-culturale/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Accessible Guide. Available online: https://www.museopertutti.org/guida-accessibile/ (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Greco, R.; Sannazzaro, A. Testimonianze di accessibilità nei musei e nelle aree archeologiche della Basilicata: L’attività di Archeoworking. BTA—Boll. Telemat. Dell’Arte 2024, 1–9, ISSN 1127-4883. Available online: https://www.bta.it/txt/a0/09/BTA-Bollettino_Telematico_dell'Arte-Testi-bta00954.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Accomation Facilities in Basilicata. Available online: https://dovedormire.aptbasilicata.it/search (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Crafts. Available online: https://www.sassilive.it/economia/lavoro/turismo-confartigianato-in-basilicata-il-peso-delle-imprese-artigiane-e-del-165-con-la-provincia-di-matera-che-arriva-al-171/ (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Widespread Hotels. Available online: www.alberghidiffusi.it (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Holiday Homes/Farm stays. Available online: https://ecobnb.it/basilicata (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Glamping. Available online: https://www.basilicataglamping.it/ (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Bizzarri, C.; Querini, G. Economia del Turismo Sostenibile. Analisi Teorica e Casi Studio; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2006; ISBN 108846472462. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Candela, G.; Castellani, M. Stagionalità e destagionalizzazione. In L’Italia. Il Declino Economico e la Forza del Turismo. Fattori di Vulnerabilità e Potenziale Competitivo di un Settore Strategico; Celant, A., Ed.; Marchesi: Roma, Italy, 2009; pp. 251–259. ISBN 8886248105. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Cannas, R. An Overview of Tourism Seasonality: Key Concepts and Policies. AlmaTourism J. Tour. Cult. Territ. Dev. 2012, 5, 40–58. [Google Scholar]

- Formato, R.; Presenza, A. Management della Destinazione Turistica. Attori, Strategie e Indicatori di Performance; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2018; ISBN 9788891779342. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Project “Via delle Meraviglie”. Available online: https://youtu.be/UwAZXw7hokw (accessed on 4 May 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sannazzaro, A.; Del Lungo, S.; Potenza, M.R.; Gizzi, F.T. Revitalizing Inner Areas Through Thematic Cultural Routes and Multifaceted Tourism Experiences. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4701. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104701

Sannazzaro A, Del Lungo S, Potenza MR, Gizzi FT. Revitalizing Inner Areas Through Thematic Cultural Routes and Multifaceted Tourism Experiences. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4701. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104701

Chicago/Turabian StyleSannazzaro, Annarita, Stefano Del Lungo, Maria Rosaria Potenza, and Fabrizio Terenzio Gizzi. 2025. "Revitalizing Inner Areas Through Thematic Cultural Routes and Multifaceted Tourism Experiences" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4701. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104701

APA StyleSannazzaro, A., Del Lungo, S., Potenza, M. R., & Gizzi, F. T. (2025). Revitalizing Inner Areas Through Thematic Cultural Routes and Multifaceted Tourism Experiences. Sustainability, 17(10), 4701. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104701