From Cognition to Conservation: Applying Grid–Group Cultural Theory to Manage Natural Resources

Abstract

1. Introduction

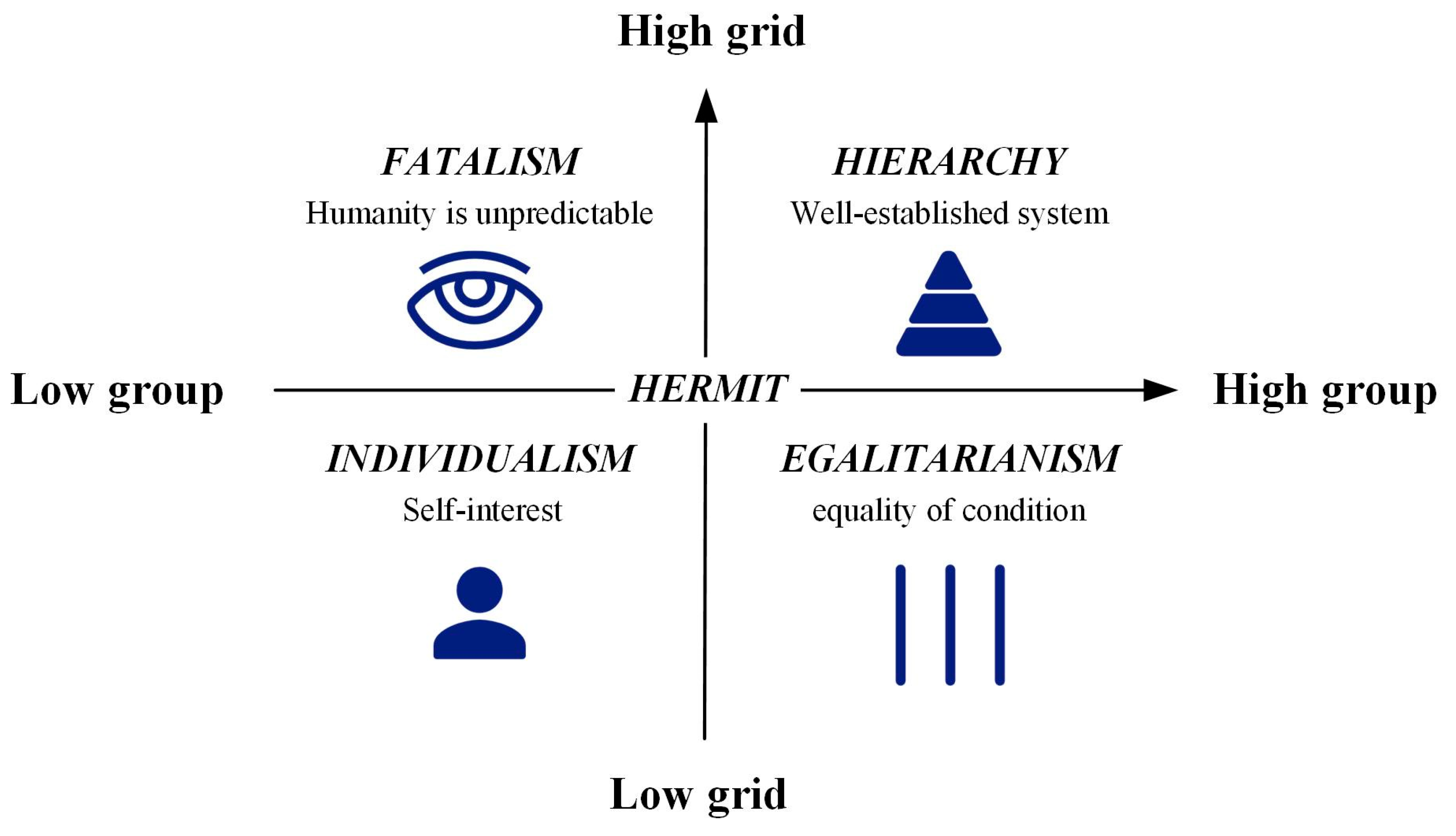

2. Development of Cultural Theory

3. Validation of Cultural Theory

3.1. Validation from a Neuroscientific Perspective

3.2. Validation Through Comparison with Other Classification Methods

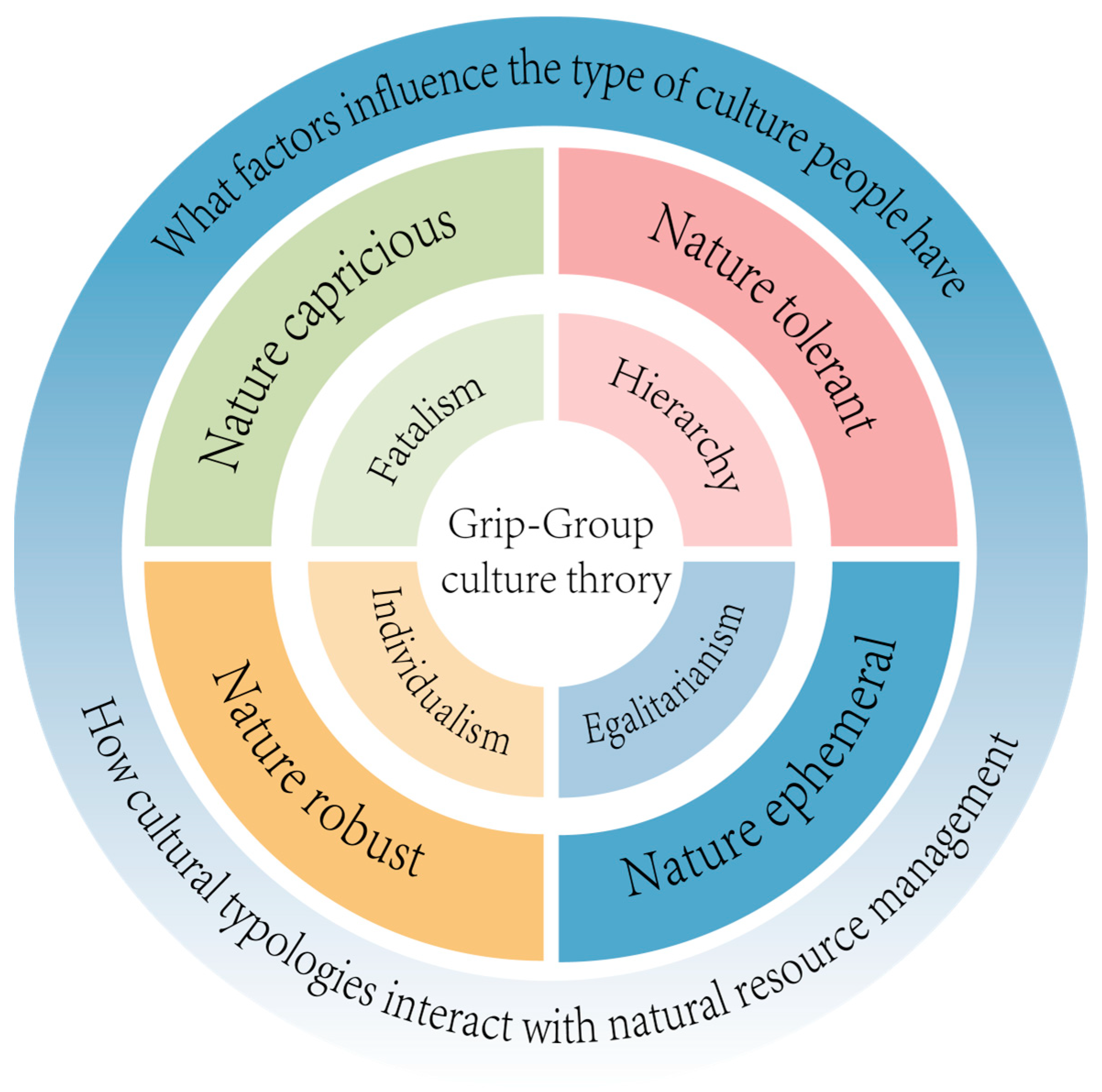

4. GGCT and Natural Resource Management

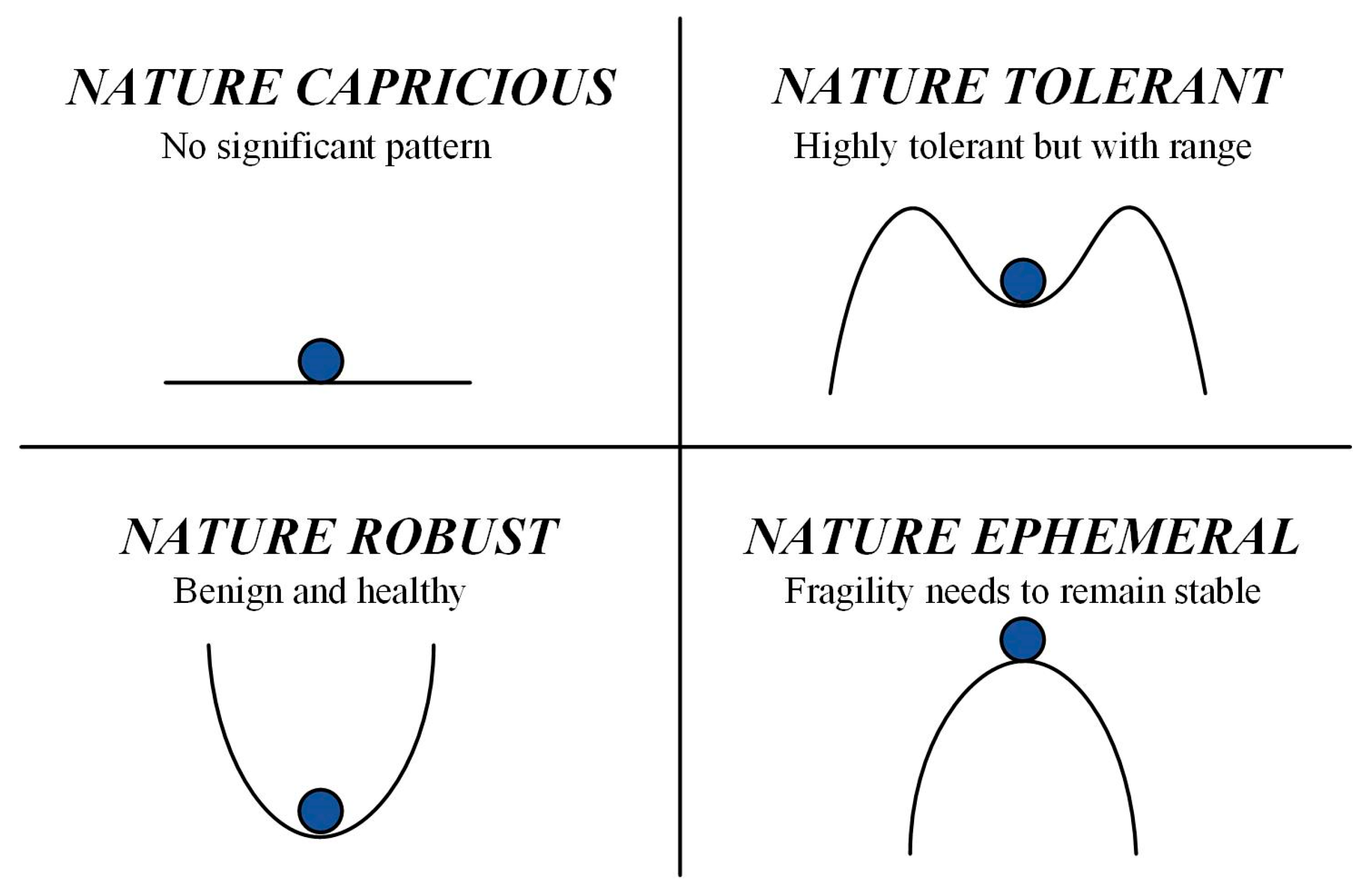

4.1. Myths of Nature

4.2. GGCT Application in Natural Resource Management

4.2.1. Differences Between Cultural Types in Natural Resource Management

4.2.2. What Factors Image the Type of Culture in Natural Resource Management

4.2.3. Enhancing Natural Resource Management Through Cultural Theory

5. Discussion

5.1. How Cultural Types of Different Objects Affect Natural Resource Management

5.2. Factors Influencing the Type of Culture

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ali, M.A.; Kamraju, M. The Future of Natural Resource Management. In Natural Resources and Society: Understanding the Complex Relationship Between Humans and the Environment; Earth and Environmental Sciences Library; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondolleck, J.M.; Manring, N.J.; Crowfoot, J.E. Teetering at the top of the ladder: The experience of citizen group participants in alternative dispute resolution processes. Sociol. Perspect. 1996, 39, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, O. The Challenge of Integrating Deliberation and Expertise: Participation and Discourse in Risk Management. In Risk Analysis and Society: An Interdisciplinary Characterization of the Field, 1st ed.; McDaniels, T., Small., M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; pp. 289–366. [Google Scholar]

- Kahan, D.M. Cultural Cognition as a Conception of the Cultural Theory of Risk. In Handbook of Risk Theory; Roeser, S., Hillerbrand, R., Sandin, P., Peterson, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluckhohn, C. The Study of Culture. In The Policy Sciences; Lerner, D., Lasswell, H.D., Eds.; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1951; pp. 86–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kroeber, A.L.; Parsons, T. The Concepts of Culture and of Social System. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1958, 23, 582–583. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Culture and organizations. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 1980, 10, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Report of the United Nations Conference on Human Environment. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/conferences/environment/stockholm1972 (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- UN United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED). Available online: https://www.un.org/en/conferences/environment/rio1992 (accessed on 23 July 2021).

- Liu, Y.H.; Ge, Q.S.; Zhang, X.Q. Thoughts about the development for the research of human dimensions on global environmental changes in China. Sci. Found. China 2005, 1, 3–9. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Luo, S. Consumers’ intention and cognition for low-carbon behavior: A case study of Hangzhou in China. Energies 2020, 13, 440–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hurlstone, M.J.; Leviston, Z.; Walker, I.; Lawrence, C. Climate change from a distance: An analysis of construal level and psychological distance from climate change. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, W.; Hine, D.W.; Loi, N.M.; Thorsteinsson, E.B.; Phillips, W.J. Cultural worldviews and environmental risk perceptions: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 440–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippl, S. Cultural theory and risk perception: A proposal for a better measurement. J. Risk Res. 2002, 5, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, E.; Marcel, M. Primitive Classification; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, B. Class, Codes and Control, Vol. I: Theoretical Studies Towards a Sociology of Language; Routledge and Kegan Paul: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of the Concepts of Pollution and Taboo, 1st ed.; Routledge and Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M. Natural Symbols: Explorations in Cosmology, 1st ed.; Barrie & Rockliff: London, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M. Natural Symbols, Explorations in Cosmology, Vintage Books ed.; Barrie & Jenkins: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.H. Society, Physical Symbolism, and Cosmology—Reading “Natural Symbols” and Evaluating Differences Between Two Versions. Master’s Thesis, Minzu University of China, Beijing, China, 2010. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Spickard, J.V. A guide to Mary Douglas’s three versions of grid/group theory. Sociol. Anal. 1989, 50, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.G. Grid/group analysis and historical science research. Stud. Dialectics Nat. 1992, 8, 36–42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M. Essays in the Sociology of Perception, 1st ed.; Routledge and Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1982; Volume 23, Chapter 3; p. 318. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M.; Ney, S. Missing Persons: A Critique of Personhood in the Social Sciences. In Anthropological Quarterly; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1998; p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M.; Wildavsky, A. Risk and Culture: An Essay on the Selection of Technological and Environmental Dangers; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner, S. Cultural theory and risk analysis. In Social Theories of Risk, 1st ed.; Sheldon, K., Dominic, G., Eds.; Praeger: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 83–115. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, M.; Richard, E.; Aaron, W. Cultural Theory, 1st ed.; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, M. A Three-Dimensional Model. In Essays in the Sociology of Perception, 1st ed.; Routledge and Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, M. The Problem of the Center: An Autonomous Cosmology, 1st ed.; Routledge and Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Mamadouh, V. Grid-group cultural theory: An introduction. GeoJournal 1999, 47, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, V. Body, brain, and culture. Zygon J. Relig. Sci. 1983, 18, 221–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, V.; Turner, E. On the edge of the bush: Anthropology as experience. J. Am. Folk. 1985, 100, 342. [Google Scholar]

- Meloni, M. How biology became social, and what it means for social theory. Sociol. Rev. 2014, 62, 593–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verweij, M.; Senior, T.J.; Domínguez, D.J.F.; Turner, R. Emotion, rationality, and decision-making: How to link affective and social neuroscience with social theory. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehaene, S. Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How We Read; Penguin: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Changeux, J.P. The Good, the True, and the Beautiful: A Neuronal Approach, 1st ed.; Yale University Press: New Haven, UK; London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Damasio, A. Self Comes to Mind: Constructing the Conscious Brain, 1st ed.; Pantheon: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, W. Der Beobachter im Gehirn: Essays zur Hirnforschung; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Verweij, M.; Damasio, A. The Somatic Marker Hypothesis and Political Life. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zeki, S. Inner Vision: An Exploration of Art and the Brain; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, R. Culture and the human brain. Anthropol. Humanism. 2001, 26, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.; Whitehead, C. How collective representations can change the structure of the brain. J. Conscious. Stud. 2008, 15, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, L.M.; Hauser, W.J. A re-inquiry of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions: A call for 21st century cross-cultural research. Mark. Manag. J. 2008, 18, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.; Jan Hofstede, G.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind; Mc Graw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 27–296. [Google Scholar]

- Pokorny, B.; Schanz, H. Empirical determination of political cultures as a basis for effective coordination of forest management systems. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2003, 16, 887–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singelis, T.M.; Triandis, H.C.; Bhawuk, D.P.S.; Gelfand, M.J. Horizontal and Vertical Dimensions of Individualism and Collectivism: A Theoretical and Measurement Refinement. Cross-Cult. Res. 1995, 29, 240–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C.; Gelfand, M.J. A theory of individualism and collectivism. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology; Van Lange, P.A.M., Kruglanski, A.W., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2012; pp. 498–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Aksoy, L. Dimensionality of individualism–collectivism and measurement equivalence of Triandis and Gelfand’s scale. J. Bus. Psychol. 2007, 21, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shweder, R.A.; Much, N.C.; Mahapatra, M.; Park, L. The “big three” of morality (autonomy, community, and divinity), and the “big three” explanations of suffering. In Morality and Health; Brandt, A., Rozin, P., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 119–169. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, T.S.; Fiske, A.P. Moral psychology is relationship regulation: Moral motives for unity, hierarchy, equality, and proportionality. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 118, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.; Haidt, J.; Koleva, S.; Motyl, M.; Iyer, R.; Wojcik, S.P.; Ditto, P.H. Moral foundations theory: The pragmatic validity of moral pluralism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 47, 55–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verweij, M.; Alexandrova, P.; Jacobsen, H.; Béziat, P.; Branduse, D.; Dege, Y.; Hensing, J.; Hollway, J.; Kliem, L.; Ponce, G.; et al. Four galore? The overlap between Mary Douglas’s grid-group typology and other highly cited social science classifications. Sociol. Theory 2020, 38, 263–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambardella, C.; Fath, B.D.; Werdenigg, A.; Gulas, C.; Katzmair, H. Assessing the Operationalization of Cultural Theory through Surveys Investigating the Social Aspects of Climate Change Policy Making. Weather. Clim. Soc. 2020, 12, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildyard, N.; Hedge, P.; Wolvekamp, P.; Reddy, S. Same platform, different train: The politics of participation. Unasylva 1998, 49, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Billgren, C.; Holmén, H. Approaching reality: Comparing stakeholder analysis and cultural theory in the context of natural resource management. Land Use Policy 2008, 25, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehlera, J.; Rayner, S.; Katuvaa, J.; Thomsona, P.; Hope, R. A cultural theory of drinking water risks, values and institutional change. Glob. Environ. Change 2018, 50, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.J.; Zhong, F.L.; Xu, Z.M. Effect of Worldview Differences on Public Participation in Water Resources Management: A case study of Ganzhou District in the Middle Heihe River Basin. China Rural. Water Hydrower 2012, 10, 53–57+64. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.J.; Zhong, F.L.; Xu, Z.M.; Yin, X.J. Appying Cultural Theory and Fuzzy Network Analysis to Evaluate the Optimal Water Resources Management Style in the Middle Reaches of the Heihe River. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 2013, 35, 224–232. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yin, X.J.; Zhong, F.L.; Xu, Z.M. Water Resources Cognitive Analysis Based on Gird-Group Culture Theory: A Case Study of Famers in Ganzhou District in the Middle Reach of Heihe River. J. Nat. Resour. 2014, 29, 166–176. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, F.L.; Yin, X.J.; Xu, Z.M. Resident Culture Values and Natural Environment Perception in Ganzhou District in the Middle Reaches of Heihe River. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 2012, 34, 972–982. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, B.E. Clumsiness and Elegance in Environmental Management: Applying Cultural Theory to the History of Whaling. Environ. Politics 2015, 25, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.W. Some Aspects of Measuring Education. Soc. Sci. Res. 1995, 24, 215–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marris, C.; Langford, I.H.; O’Riordan, T. A quantitative test of the cultural theory of risk perceptions: Comparison with the psychometric paradigm. Risk Anal. 1998, 18, 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoogstra-Klein, M.A.; Permadi, D.B.; Yasmi, Y. The value of cultural theory for participatory processes in natural resource management. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 20, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, N.C.; Moran, C.J.; Kastelle, T. Implementing an integrated approach to water management by matching problem complexity with management responses: A case study of a mine site water committee. Clean. Prod. 2013, 52, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantoh, H.B.; Mckay, T. Assessing community-based water management and governance systems in North-West Cameroon using a Cultural Theory and Systems Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 290, 125804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skuzinski, T. The Risk of Regional Governance: Cultural Theory and Interlocal Cooperation; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kolobov, R.Y.; Ditsevich, Y.B. Rol’ Bernskoj konvencii 1979 g. v regulirovanii deyatel’nosti po sohraneniyu biora-znoobraziya na Bajkal’skoj prirodnoj territorii [The Significance of the 1979 Bern Convention in the Legal Regulation of Biodiversity Conservation in the Baikal Natural Territory]. Sibirskij yuridicheskij vestnik [Sib. Law Her.] 2022, 1, 119–126. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Duration | Literary Work | Main Theories |

|---|---|---|

| 1966 | Purity and Danger | She proposed initial ideas about primitive worldviews, external boundaries, internal boundaries, and the fragmentation and reorganization of systems concerning human societies and classifications [13]. |

| 1970 | Natural Symbols | She first introduced the concepts of “grid” and “group”. “Group” measures the external boundaries of a social unit, while “grid” measures the internal boundaries of a social unit. |

| 1973 | Natural Symbols (Revised Edition) | The two versions contained different understandings, leading to confusion in the definitions of grid and group, which made it difficult for people to comprehend her theory [14,15,16]. |

| 1978 | Cultural Tendencies | She defined grid as the “dimension of individualization” and group as the “dimension of social integration” [17,18]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quan, X.; Song, X.; Nguyen, T.P. From Cognition to Conservation: Applying Grid–Group Cultural Theory to Manage Natural Resources. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4613. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104613

Quan X, Song X, Nguyen TP. From Cognition to Conservation: Applying Grid–Group Cultural Theory to Manage Natural Resources. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4613. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104613

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuan, Xuefeng, Xiaoyu Song, and Thi Phuong Nguyen. 2025. "From Cognition to Conservation: Applying Grid–Group Cultural Theory to Manage Natural Resources" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4613. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104613

APA StyleQuan, X., Song, X., & Nguyen, T. P. (2025). From Cognition to Conservation: Applying Grid–Group Cultural Theory to Manage Natural Resources. Sustainability, 17(10), 4613. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104613