1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly altered the landscape of entrepreneurial intentions among young students, prompting a re-evaluation of how psychological determinants (such as attitudes, social norms, and behavioral control) influence their entrepreneurial aspirations.

Research indicates that the pandemic not only evoked feelings of fear and uncertainty among potential young entrepreneurs but also led to increased recognition of entrepreneurship as a viable career path due to changing economic dynamics and job market limitations [

1,

2]. Furthermore, the crisis has prompted a shift in educational approaches, with entrepreneurship education playing a pivotal role in cultivating an entrepreneurial mindset and enhancing students’ perceived control over their entrepreneurial intentions (EIs) [

3]. By understanding the interplay between attitudes, social norms, behavioral control, and entrepreneurial intentions amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, scholars can better inform educational strategies and policies aimed at fostering a new generation of entrepreneurs equipped to navigate uncertainties [

4,

5].

However, for Romania, as well as other emerging countries, the increase in innovative businesses and entrepreneurial activities is a major issue [

6] on which the sustainability of future growth depends. In shaping the economic landscape of these countries, entrepreneurship plays an important role. Studies [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], supported by country-specific reports and statistics [

13,

14,

15], have shown that fostering an entrepreneurial mindset and providing appropriate education and tools to the younger population represent the premises for developing entrepreneurial potential that could lead to entrepreneurial intent and action. Thus, understanding the entrepreneurial intent of the younger population, in general, is an important step in tailoring entrepreneurial education to ultimately shape the entrepreneurial outlook of a country. For Romania, as well as other emerging countries, in particular, this approach is of uttermost importance as these countries’ economic growth heavily depends on entrepreneurs [

13,

15,

16]. Thus, a bottom-up approach is warranted, as any change should start with a better understanding of the status quo. Consequently, relevant data should be collected from the problem owners (future entrepreneurial solution providers)—in this context, the younger population of any (emerging) country. In refining the problem owners, as both entrepreneurial education has been shown to play an important role in shaping entrepreneurial intent [

15] and emerging entrepreneurs are habitually higher education alumni [

14], exposure to education should factor in. In this context, problem owners are young people enrolled in a higher education program, in the process of learning about entrepreneurship, exposed to the entrepreneurial ecosystem, and eager to make their mark on the market.

Hence, analyzing the entrepreneurial intent of young students in Romania, a country that presents similar characteristics to other emerging countries, is relevant for understanding what future actions are needed (in terms of educational development, government support, partnerships, etc.) to ensure an appropriate entrepreneurial venue and entrepreneurial success for the younger population, with the overall goal of contributing to enhancing the economic future of these countries.

Specific country studies, limited in number, have focused on either the pre-pandemic period [

12,

17,

18,

19,

20] or the post-pandemic period [

9,

11,

21,

22,

23], with no longitudinal research conducted. Understanding how students’ intentions have evolved over time can provide insights into the impact of contextual factors on their entrepreneurial endeavors, especially in times of crisis. Furthermore, longitudinal studies can contribute to the Theory of Planned Behavior by exploring how shifts in perceived behavioral control, stemming from changes in resource availability, access to funding, and support, affect students’ entrepreneurial intentions in a dynamic setting like that created by the pandemic.

With our study, starting from the Theory of Planned Behavior as a conceptual model, we aim to identify if attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioral control have a positive impact on Romanian students’ entrepreneurial intent pre- and post-COVID-19 pandemic. We want to analyze if the influences related to EI are unchanged whether we look at the period before or after the pandemic. Consequently, we have formulated the following research questions: What changes have occurred in the attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioral control of young Romanian students concerning entrepreneurship from the pre-pandemic period to the post-pandemic period? How do the changes in attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioral control of young Romanian students influence their entrepreneurial intentions in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic? These questions aim to explore the distinctions in factors influencing entrepreneurial intentions before and after the COVID-19 pandemic, an area that is notably under-researched in the Romanian context.

Using an SEM model to test our constructs across the considered timeframe, our main findings revealed that attitudes and perceived behavioral control have a strong impact on students’ entrepreneurial intent for both cohorts analyzed, albeit in a reverse sense, while social norms only influence the entrepreneurial intent of the post-COVID-19 group. In addition, results show that the propensity towards entrepreneurship is stronger for the post-COVID-19 group. Mainly, for the analyzed groups, difficult access to loans and grants can motivate individuals to pursue entrepreneurial activities, even if these conditions are challenging. Poor market opportunities, lack of jobs, and the opportunity to take over the family business can boost the entrepreneurial intention of students, even in challenging and uncertain environmental factors.

In line with our purpose, we structured the paper as follows. Building on the broad context presented, we next analyzed the relevant literature review in order to underline the opportunity, originality, and novelty of our research and further substantiate our research hypotheses and we presented our conceptual model. In the subsequent section, we outlined the research methodology, starting with the research context, and explaining the data and model. In the following sections, we present our results and discuss our analysis, and finally, we conclude by highlighting the contributions, limitations, and further research paths of our study.

2. Theoretical Background and Conceptual Model

2.1. Literature Review

Aligned with our research focus and to effectively identify pertinent scientific articles, we employed a systematic approach for the literature review. We searched articles in databases including Scopus, Web of Science, JSTOR, and Google Scholar, as well as renowned organization websites for relevant reports, using keywords such as “entrepreneurial intention/intent”, “entrepreneurship/COVID-19”, “entrepreneurship education”, “psychological factors in entrepreneurship”, “Theory of Planned Behavior”, and variations thereof. We did not apply time constraints in our literature review search in order to include both later foundational concepts and recent studies addressing the ongoing implications for entrepreneurial intention in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, we considered a three-step exclusion process as follows: (1) articles that were not written in English and Romanian were excluded from the overall references collected; (2) studies that were opinion pieces were excluded; and (3) for the empirical research, articles that did not focus on the entrepreneurial intention construct or focused on unrelated psychological constructs were also set aside.

The literature review reveals that the impact of entrepreneurship on society and its role as a key factor in societal development has piqued the interest of researchers and decision-makers, leading to numerous studies in the field [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Most authors explore the relationship between entrepreneurship and economic growth, believing that entrepreneurial activity acts as an essential catalyst for sustainable economic development [

28,

32,

33]. According to The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development [

34], entrepreneurial activity significantly influences the pace and quality of a country’s socio-economic development.

Entrepreneurs are seen as true ‘agents of change’ who initiate and establish new businesses, experiment with new production techniques, introduce new products, and create new markets [

35,

36]. They continuously seek new opportunities, exploring and exploiting market chances while encouraging the efficient mobilization of capital and skills to develop innovative products and services [

37].

Considering that entrepreneurship is a key factor of progress and development, promoting youth entrepreneurial activity should be a priority in order to build an innovation-based economy [

38,

39,

40]. Youth tend to be more proactive, innovative, and creative, exhibiting greater openness to change compared to the adult population. As a result, they represent a significant strategic asset for any national economy [

41].

An increased interest has also been given to the idea of entrepreneurship as a viable alternative to increase labor market absorption among students [

42,

43,

44]. As it is impossible for a country’s government to provide jobs for all university graduates, it is essential that they change their mindset when looking for a job and reorient themselves towards all that the ‘entrepreneurial revolution’ has to offer [

45]. This approach is based on the following simple reasoning: some young entrepreneurs with a solid entrepreneurial education will certainly be able to initiate new businesses with a higher degree of sustainability and with faster development, compared to the competition [

46]. On the other hand, the continuous process of restructuring organizations due to increased global competition has significantly diminished the appeal of traditional employment within companies, leading to a greater inclination among students to pursue entrepreneurial ventures [

47]. In addition, the reality that, in recent years, the level of unemployment among higher education graduates has increased has significantly led to an increase in people making the decision to start a new business [

48].

The development and implementation of effective policies that support and promote entrepreneurship among students are directly linked with identifying the drivers that foster their intention to become entrepreneurs [

42,

49,

50]. Thus, entrepreneurship is a complex activity that depends on a multitude of factors (personal, socio-demographic, psychological, economic, political, and cultural) as well as the mindset of an entrepreneur, meaning that the behavior related to all these factors plays an essential role in identifying an effective pattern to predict entrepreneurial intent among students [

51,

52].

Within the scientific literature, entrepreneurial intent is seen as a conscious, deliberate, and planned state of mind that precedes specific actions, thereby allowing the identification of certain types of behavior [

53,

54].

Regarding activities with entrepreneurial characteristics, entrepreneurial intent can be approached as a ‘self-recognized belief’ of an individual willing to become an entrepreneur or a ‘conscious conviction’ of a person intending to initiate a new business in the future [

22,

55,

56,

57]. From another perspective, entrepreneurial intent can be associated with a state of mind in which an individual chooses to work for themself rather than for others [

58]. Despite the diverse viewpoints concerning the concept of entrepreneurial intent, entrepreneurial theory widely accepts that it represents the key element in starting a business venture [

49,

50,

59].

In terms of behavioral change, given that entrepreneurial intent among young people is sensitive to many aspects, starting with the end of 2019, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was highly significant, generating social, financial, and economic difficulties and uncertainty on a worldwide scale [

60]. During these hard times, many organizations have had financial difficulties, were closed, or had to rethink their business model [

61,

62]. As entrepreneurship has a great capacity to mitigate the negative effects of the pandemic, in terms of socio-economic development, citizens’ well-being added value and wealth [

63,

64], encouraging students’ entrepreneurial intent, and their individual talents should be part of the solution [

55,

65,

66].

Understanding and predicting new business initiation requires research using theory-driven models that can reflect the complex perception-based processes underlying intentional, planned behaviors such as the intent to start a new business [

67].

The most widely used model in analyzing entrepreneurial behavior is the Theory of Planned Behavior, and its capacity and effectiveness in anticipating entrepreneurial intent have been highlighted in several studies [

28,

51,

55,

68,

69,

70]. Developed by Ajzen in 1991 [

71], the model explains how the socio-cultural environment influences an individual’s behavior with the intention to adopt a specific behavior, mediated by three categories of factors: attitude towards a particular behavior, perceived behavioral control, and subjective norms. The use of the three TPB factors in investigating students’ entrepreneurial intentions has been previously validated by studies that examined this relationship [

11,

12,

72,

73,

74,

75], with the factors treated separately or together.

An individual’s attitude towards a specific behavior refers to how they feel about or are attracted to a particular action. In the context of starting a business, the role of an entrepreneur can either be seen as appealing or unappealing [

76]. The attractiveness of entrepreneurship depends fundamentally on the strength of beliefs regarding the outcomes of the behavior (i.e., whether the outcome is likely or not) and the evaluation of potential results (i.e., whether the outcome is positive or not) [

77]. Generally, individuals who exhibit greater openness to entrepreneurship are more capable of detecting new market opportunities and are more willing to take on the associated risks [

52]. Most empirical studies focusing on how attitudes towards a specific behavior influence entrepreneurial intent reveal a positive relationship between the two, suggesting that attitude can be a critical influencing factor of entrepreneurial intent [

46,

68,

76,

78]. However, there are studies that reveal no direct relationship between attitude and an individual’s desire to become an entrepreneur, the lack of entrepreneurial experience being the main explanation [

52,

79].

Perceived behavioral control reflects an individual’s belief in their ability to control a given behavior, and from this perspective, individuals are more likely to adopt a certain behavior when they feel that they will be successful in their undertaking [

47]. Most specialized studies underline that an individual’s self-perception of their personal capability to carry out a specific action significantly influences their intention to engage in that action, indicating a positive relationship between perceived behavioral control and entrepreneurial intent [

55,

70,

80,

81,

82]. Therefore, individuals who perceive a higher level of control over their behavior are more confident in their ability to initiate and engage in a new business venture [

83].

Finally, social norms can be viewed as relevant factors in shaping entrepreneurial intent, as they reflect the ‘social pressure’ exerted on adopting or not adopting a certain behavior [

39]. People tend to develop personal beliefs regarding the acceptance or rejection of certain behaviors, and a favorable position towards entrepreneurship expressed by relevant individuals or social circles (e.g., family, friends, or colleagues) can influence an individual’s intention in this regard [

57,

65]. Studies focusing on how social norms contribute to entrepreneurial intent formation have led to different results. Most studies highlight the positive influence of social norms on an individual’s intent to become an entrepreneur [

22,

48,

79]. However, there are also studies suggesting that social norms do not represent a determining component of entrepreneurial intent [

27,

78,

84]. This highlights the complexities associated with the influence of norms, particularly in collectivist cultures, where social expectations are more pronounced.

2.2. Research Hypotheses and Conceptual Model

In the context of our research, pre-COVID-19 findings from studies involving Romanian students [

17,

18,

19,

20,

85] revealed that entrepreneurial personality traits positively impact students’ entrepreneurial intent.

Conducted in 2019 on a sample of 138 Romanian engineering students, the study of Herman [

17] underlines that “a high level of entrepreneurial personality traits such as risk-taking propensity, innovativeness, sense of self-confidence, optimism and competitiveness enhance propensity to entrepreneurial career of students”.

On the other hand, the research of Vodă et al. [

18] revealed that lack of control, need for achievement and entrepreneurial education are relevant determinants of entrepreneurial intent among Romanian students. Moreover, respondents’ gender also has an important influence on entrepreneurial intent, with males being more inclined to become entrepreneurs than females, which is in line with other studies that used samples of Romanian students [

19,

20].

Baciu et al. [

12] concluded that, for Romanian students, the levels of perceived behavioral control in entrepreneurship are shaped not only by personality traits but also by additional factors, such as empathy and assertiveness. These factors serve as personal resources for individuals and contribute to the shaping of their behavior.

More recently, the study of Balgiu and Simionescu-Panait [

11] conducted on 700 Romanian students revealed that both attitudes oriented toward entrepreneurship and perceived behavioral control have a high impact on EI, with attitudes registering the highest impact.

Although the study did not address the context of a crisis situation, Nițu et al. [

9] found a direct relationship between perceived sustainable entrepreneurial desire and sustainable entrepreneurial intentions when analyzing a sample of 211 Romanian students, as did the study of Gomes et al. [

57], who underlined that no changes were observed in the period before or during the pandemic.

Accordingly, we have formulated:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Attitude has a positive impact on Romanian students’ EI, regardless of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Research demonstrates that high levels of perceived control positively correlate with entrepreneurial intentions. Iakovleva et al. [

80] provide evidence that individuals who believe they can successfully engage in entrepreneurial activities are more likely to develop strong entrepreneurial intentions. This is consistent across various demographics.

Agung et al. [

86] highlight that PBC significantly influences entrepreneurial intentions, reinforcing the notion that individuals who believe they can successfully undertake entrepreneurial tasks are more likely to express strong entrepreneurial preferences. This aligns with the foundational tenets of the TPB, indicating that perceived control positively correlates with EI, regardless of external circumstances such as a pandemic. Furthermore, Duong [

87] emphasizes that perceived behavioral control serves as a crucial mediator in the relationship between entrepreneurship education and EI. This study illustrates that as students’ belief in their control over entrepreneurial activities strengthens, their intentions to engage in entrepreneurship also increase.

Nițu et al. [

9] showed that behavioral factors (personal attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control), as mediating variables, are predictors of perceived sustainable entrepreneurial desire for 211 Romanian students.

As such, we developed:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Perceived behavioral control has a positive impact on Romanian students’ EI, regardless of the COVID-19 pandemic.

As for social norms, findings from Heuer and Liñán [

88] argue that subjective norms exert a positive influence on entrepreneurial intentions. Their findings indicate that when students perceive supportive social expectations regarding entrepreneurship, their intentions to engage in entrepreneurial activities increase.

Paray and Kumar [

8] emphasize that students who perceive a positive social environment regarding entrepreneurship are more likely to develop intentions to engage in entrepreneurial behavior, highlighting that social norms positively contribute to EI among students. Joensuu-Salo et al. [

89] suggest that subjective norms do play a role in influencing entrepreneurial intentions, although they may exert a weaker impact compared to attitudes.

Furdui et al. [

7] indicate that for Romanian students, a culture favorable to entrepreneurship significantly enhances students’ motivations to start businesses. The findings of Trif et al. [

23] reveal that a supportive entrepreneurial environment significantly affects students’ entrepreneurial intentions. The study shows that when students perceive a social context that values entrepreneurship, it positively influences their intentions to engage in entrepreneurial activities.

Thus, we developed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Social norms have a positive impact on Romanian students’ EI, regardless of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Regarding behavioral change and given that entrepreneurial intent among young people is sensitive to many aspects, starting with the end of 2019, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was highly significant, generating social, financial, and economic difficulties and uncertainty on a worldwide scale [

60].

As for the pre- and post-pandemic trends in EI, the study of Badea [

21] showed that the pandemic had negatively affected the entrepreneurial intention of young people. Before the pandemic, 35.6% of young people wanted to start their own business, with 24.4% undecided after the pandemic because of restrictions and uncertainty, while 1.6% gave up on starting a business. Therefore, they concluded that the COVID-19 pandemic has caused entrepreneurship disruptions and challenges for current and future businesses. These conclusions are in line with the study of Botezat et al. [

22], who revealed that students’ entrepreneurial intentions increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting that individuals with higher levels of entrepreneurial intention have changed less than those with lower initial scores.

However, Gomes et al. [

57] underline that the motivational dimension, attitude towards behavior, and perceived behavioral control had a positive impact on entrepreneurial intentions during the pandemic, while subjective norms had a negative impact on entrepreneurial intentions, and these influences are unchanged in the period before or during the pandemic. Additionally, Lopes et al. [

77] found that despite the significant macroeconomic changes triggered by the pandemic, the entrepreneurial intentions of students did not diminish. Rather, students demonstrated a continued interest in entrepreneurship, suggesting that the pandemic may have acted as a catalyst for entrepreneurial aspirations instead of a deterrent.

Therefore, we formulated:

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Romanian students’ entrepreneurial intent shows a similar trend before and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

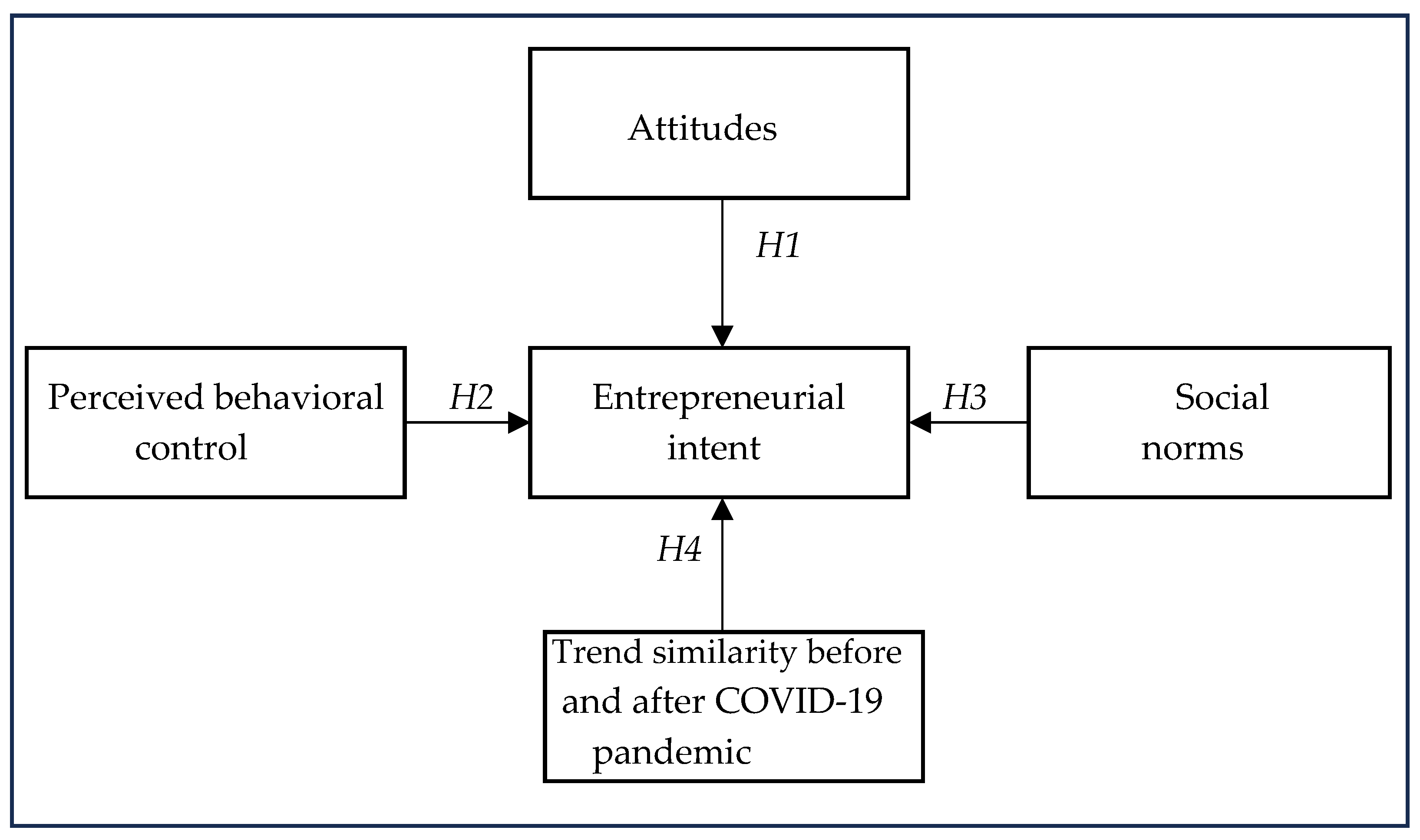

Considering our research framework and hypotheses, we next developed the theoretical model (

Figure 1) that assumes a direct and strong influence of TPB constructs on entrepreneurial intention for Romanian students, irrespective of the pandemic. We propose that as students develop greater confidence in their capabilities, the likelihood of their intentions translating into concrete actions increases. A positive attitude towards entrepreneurship enhances the likelihood of students feeling motivated to pursue entrepreneurial ventures. Studies indicate that favorable attitudes reinforce the commitment to entrepreneurial paths and can lead to increased entrepreneurial intention [

90,

91]. Perceived behavioral control refers to individuals’ beliefs about the ease or difficulty of performing entrepreneurial behavior, which plays a critical role in determining intention [

92]. Research shows that enhancing self-efficacy and mitigating perceived barriers could significantly impact students’ entrepreneurial intentions [

93]. Social norms encompass the perceived societal pressures or expectations that individuals face in pursuing entrepreneurial activities. Paiva et al. [

94] emphasize that positive social environments and supportive norms can increase students’ intentions to engage in entrepreneurship. Furthermore, perceptions of social endorsement contribute to a stronger motivation towards entrepreneurial activities. As for trends, we consider entrepreneurial intent resilient, despite external shocks. Studies have shown that certain core motivations for entrepreneurship persist through crises, indicating that the foundational elements of entrepreneurial intention may remain stable [

57,

77].

The originality of the theoretical model resides in including aspects related to the resilience of entrepreneurial intent during periods of crisis.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Context

According to the 2024 EU youth report [

95], the proportion of self-employed individuals within the young population (15–29 years old) active in the labor market in Romania is among the highest in the European Union, but the country is also recording one of the largest decreases in this percentage in recent years. Romania ranks 7th in the EU in terms of young people declaring themselves self-employed in 2023: 8.8%. At the EU level, amid the reasons that drive people to choose this path in the labor market, the most important ones are related to lifestyle, not profitability: independence, flexible working conditions, and a sense of fulfillment. The same report also indicates that Romania is among the few countries, mainly in Eastern and Southern Europe, that do not offer support measures for entrepreneurship through non-formal learning.

From another perspective, Romania ranks only 36th out of 51 economies participating in the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM Global) for 2023 [

16]; however, over 63% of Romanians believe that there are favorable conditions to start a business in the area where they live. The analysis also found that fewer entrepreneurs in Romania launch new companies when compared to the global average, but those who do tend to maintain their businesses beyond the initial stages.

In this landscape, the western region of Romania, with the second highest GDP per capita in the country, after the capital region (Bucharest-Ilfov) [

13], shows a similar entrepreneurial trend to the national one. From the total number of entrepreneurs in the region, the least represented are entrepreneurs under the age of 29, with a value of 8.24% [

15], similar to the national one (8.8%). A possible explanation would be the presence of barriers to entry into business (lack of working capital, information, hostile business environment, lack of appropriate programs to stimulate young entrepreneurs, corruption, etc.) but also lack of experience. In addition, many young people from Romania choose to immigrate to Europe for competitive and higher-paid jobs, including those from the western region as they benefit from both geographical positioning and a multicultural environment. Furthermore, 36.45% of the total number of entrepreneurs in the region are women (36.57% in Romania), which is a significant share when compared to other countries in Europe and the world.

In the western region of Romania, the development of industrial sites has been coupled with a push for tourism enhancement, establishing a framework for entrepreneurship that builds upon local resources while aiming to create job opportunities [

96].

The role of education and technology transfer has been crucial in fostering an entrepreneurial spirit within Romanian universities. With seven state-funded and internationally recognized universities, the western region’s higher education institutions (HEIs) are actively involved in developing entrepreneurial competencies among students, through programs aimed at building entrepreneurial capabilities and offering practical support for business plan implementation. However, there is still a pronounced gap in innovation performance, with both the region and the country lagging behind its European counterparts. This disparity has been attributed to systemic challenges such as limited access to funding and a nascent support ecosystem for young entrepreneurs.

Current findings highlight that the local digital economy is ripe for development, driven by the need for improved governance frameworks that support digital startups [

97]. This need is accentuated by the rapid growth of e-commerce, particularly in response to changing consumer behaviors that have emerged post-COVID-19 [

98].

Despite these advancements, there are still challenges to be addressed. Youth entrepreneurship is still underrepresented, including in Western Romania, with local policymakers encouraged to develop strategies that promote inclusivity and provide mentorship opportunities. This demographic unique perspective could significantly alter the entrepreneurial landscape, provided they receive adequate support and role models to navigate the challenges they face.

In this context, our research is focused on young students enrolled in a national representative HEI that attracts students from all regions of the country, exposed to entrepreneurial training, as potential future entrepreneurs.

3.2. Research Design and Variables

The primary data needed for our research were collected using an online questionnaire, developed according to existing and validated measurement scales, namely based on the Entrepreneurial Intention Questionnaire (EIQ) developed by Liñán and Chen [

99]. We divided the questionnaire into two parts: the first one was dedicated to the assessment of the demographic and professional characteristics (age, sex, professional experience, level, and type of studies), while the second one aimed to assess their entrepreneurial intent (reasons and obstacles). To measure their perspective on entrepreneurial intent, we used the following variables (

Table 1).

As entrepreneurial intention is measured through self-reports (the participants’ intention to start a business in the immediate future), it should be noted that by emphasizing the development of entrepreneurial self-efficacy through education, we assert that as students gain confidence in their abilities, their intentions are more likely to convert into actionable behaviors. Studies by Andriyati et al. [

100] and Wu et al. [

101] have shown how self-efficacy mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial education and intentions, suggesting that students who perceive themselves as capable are more likely to act on their entrepreneurial aspirations.

For each of the three dimensions of TPB, the observed variables were formulated based on previous relevant research. For attitudes, the perception of lacking a viable business idea is a critical inhibitor of entrepreneurial intention. When individuals do not perceive a feasible idea, it can lead to a negative attitude and diminish their entrepreneurial aspirations [

90,

102]. The absence of partners is another significant concern; partnerships can enhance resource sharing and support, which individuals often interpret as crucial for entrepreneurial success. Those who anticipate difficulties in finding suitable partners may develop negative attitudes, affecting their entrepreneurial intentions [

103,

104].

Moreover, the lack of resources—including financial, human, and informational resources—serves as a considerable barrier affecting attitudes. Resource scarcity can engender feelings of helplessness or hopelessness, leading to a perceived lack of control over entrepreneurial outcomes [

49,

105]. Professional and personal recognition can profoundly influence individuals’ attitudes as they often weigh societal status and personal validation against the perceived risks and uncertainties associated with starting a business. Individuals driven by a need for recognition are likely to have varying attitudes toward entrepreneurship based on their belief systems and expected societal responses to entrepreneurial actions [

91,

106].

Social norms were configured as both enabling and constraining factors that reflect distinctive socio-economic pressures that may enhance or diminish the intention to engage in entrepreneurial activity. The lack of a diploma can significantly affect an individual’s perception of their social legitimacy in entrepreneurial endeavors. Individuals often internalize societal beliefs about educational qualifications being essential for successful entrepreneurship, leading to diminished self-efficacy and, consequently, lower entrepreneurial intentions [

107].

An unfavorable economic environment plays an important role in shaping social norms. When economic conditions are perceived as challenging, societal attitudes may shift towards risk aversion, reducing the collective endorsement of entrepreneurial endeavors.

Research indicates that perceived economic instability can adversely affect the perceived social support for entrepreneurship, leading to diminished entrepreneurial intentions [

108]. In such contexts, promising market opportunities may remain unexploited due to the pervasive influence of negative social norms that discourage risk-taking.

Relatedly, the role of laws and regulations also serves as a social norm in this context. When the legal environment is seen as unfavorable, individuals may perceive a lack of support for entrepreneurial initiatives, reinforcing adverse attitudes toward starting a business. This aligns with findings suggesting that when restrictive laws are perceived, they constrain potential entrepreneurial actions, thereby perpetuating negative social norms regarding entrepreneurship [

108,

109]. The lack of a robust networking environment further exacerbates these challenges. Social networks provide critical support, resources, and information that enhance entrepreneurial intentions. Without strong networks, individuals may feel isolated and unsupported, which reinforces negative social norms and limits their ability to identify and seize market opportunities. The implication is that social connections significantly influence perceptions of opportunity recognition, essential for fostering entrepreneurial intent.

Finally, the inclination to take over a family business reflects a complex interplay of social norms regarding entrepreneurship. In many cultures, family expectations can dictate career paths, leading individuals to prioritize familial legacy over independent entrepreneurial ventures. This can limit the exploration of innovative business ideas outside traditional family pursuits, thus damaging potential entrepreneurial intention [

110,

111]. The perception that family businesses offer a more secure or socially accepted path can create a normative frame that discourages individuals from seeking new entrepreneurial opportunities outside this model.

For perceived behavioral control, we combined specific factors such as the lack of entrepreneurial knowledge, difficult access to loans, difficult access to grants, the desire for independence, and the pursuit of larger gains, as they collectively influence how likely individuals feel they can successfully navigate the entrepreneurial landscape. The lack of entrepreneurial knowledge emerges as a significant factor that can adversely impact an individual’s perceived capability to engage in entrepreneurial activities. Studies demonstrate that a comprehensive understanding of business mechanisms is fundamental for enhancing self-efficacy, which directly relates to PBC [

92,

93]. Without adequate knowledge, individuals may overestimate the challenges of starting a business, leading to a diminished sense of control and thus lower entrepreneurial intentions [

93].

Furthermore, both difficult access to loans and grants can severely limit individuals’ confidence in their ability to initiate and sustain a business venture. Research indicates that perceived difficulties in obtaining financial support can significantly reduce perceived behavioral control, as individuals may believe their entrepreneurial pursuits are contingent upon external financial approval [

44,

112]. In terms of independence, unrealistic expectations paired with perceived barriers can lead to frustration and lost ambition [

113,

114]. The pursuit of larger gains motivates individuals towards entrepreneurship, but potential entrepreneurs may weigh the risks and rewards of entrepreneurship, considering the potential for financial success against the uncertainties involved. Research illustrates that when individuals perceive a high potential for substantial financial returns but simultaneously feel they lack the capability to achieve these outcomes, their entrepreneurial intentions may wane [

113,

115].

For the model items, a 5-point Likert scale was used from 1 (not at all important) to 7 (very important), adapted from previously validated instruments [

9,

11,

12,

99].

In order to ensure the reliability and validity of the questionnaire, it was pretested on a small sample of students.

In terms of sampling strategy, we applied stratified random sampling as we targeted only bachelor students. All of the university’s bachelor students, regardless of their field of study, are exposed to entrepreneurship courses during their studies as all curricula include entrepreneurship as a mandatory course in their first and second years. Thus, no other exclusion criteria were applied as all of our university’s students are equipped with entrepreneurial tools, some more than others, and all have the potential to become entrepreneurs.

The study conducted compares data gathered from two similar groups queried in different periods of time, namely 2018 (pre-COVID-19) and 2023 (post-COVID-19).

The overall sample of the study consisted of 383 bachelor students enrolled at the West University of Timisoara and residing in the western region of Romania. Based on the internal mailing lists, all beneficiaries were invited to fill out an online questionnaire (Google Forms) meant to set up their individual baseline profile. The participants received no incentives for taking part in the study and were informed about the purpose of the research.

From a total of 730 persons who received the invitation, 383 provided complete answers that were validated for the study. Thus, the response rate among the potential subjects was 52%.

From the total number of subjects who provided validated answers, 29.76% were male (114 participants), and 70.24% were female (269 participants), with 90.33% of the entire sample aged between 16 and 24. Regarding the overall professional experience, only 28% of the respondents were employed/entrepreneurs, while the rest had no professional experience at all.

It should be noted that the five-year gap between cohorts in our study’s design could introduce several potential confounds beyond the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. These confounds may stem from various factors that can affect the external validity, measurement of outcomes, and interpretation of results in research involving longitudinal or cohort studies. However, as our cohorts exhibit similar characteristics, namely they are all Romanian students, in the same life stage, with the same experiences, including entrepreneurial education, exposed to a similar historical and cultural environment, the only issue, irrespective of the pandemic, could be measurement inconsistencies. Specific metrics and tools have evolved over time, but, in order to ensure data comparability and convergence, for both cohorts included in our study, we used the questionnaire developed in 2018. We considered that any changes in questionnaire wording or structure would have influenced the interpretation and responses to items, thus potentially resulting in different understanding outcomes between cohorts.

In order to check the sampling adequacy, we have developed the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) as a measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity, presented in

Table 2:

The results indicate that Bartlett’s test of sphericity is significant, as

p < 0.05. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy exceeds 0.6 for both lots, implying that the sample size is adequate [

116].

3.3. Research Model

The research methodology employed herein is predicated upon the utilization of structural equation modeling (SEM). SEM represents a multivariate statistical approach commonly utilized in the conduct of foundational or applied research within behavioral, managerial, or quantitative social sciences [

117]. This method offers a complex underlying statistical framework capable of addressing a spectrum of research hypotheses. As a contemporary econometric technique, SEM showcases the ability to estimate intricate model correlations while concurrently examining the inherent error within the indicators [

118], thereby facilitating the construction of tailored network models aimed at aligning empirical observations with theoretical constructs [

119].

Jeon [

120] delineated several advantages associated with SEM, including its capability to apprehend latent variables and measurement equations, ascertain correlations among dependent variables, and engage in simultaneous estimation. Additionally, SEM enables the identification of direct, indirect, and total effects, the integration of multiple statistical methodologies within a unified model (comprising both measurement and structural equations), and the specification of reciprocal causal relationships among latent variables.

Many constructs measured in surveys—such as attitudes, perceptions, or intentions—are latent variables that cannot be directly observed. SEM facilitates the modeling of these latent constructs through multiple observed indicators, providing a more precise representation of theoretical concepts [

121]. SEM offers fit indices to evaluate how well models explain data, supporting rigorous refinement [

122], while also testing theories that involve mediation and moderation, exploring causal pathways [

123]. Recent advances in SEM estimation techniques, such as robust maximum likelihood and Bayesian methods, enable more effective analysis of survey data that may violate normality assumptions or involve smaller sample sizes [

124].

This method was also applied to previous studies regarding factors influencing entrepreneurial intention [

125] and the measurement of entrepreneurial intention by applying the Theory of Planned Behavior [

126]. The widespread adoption of this methodology is further explicable by the availability of diverse, readily accessible software platforms, which afford researchers efficient implementation of SEM [

120].

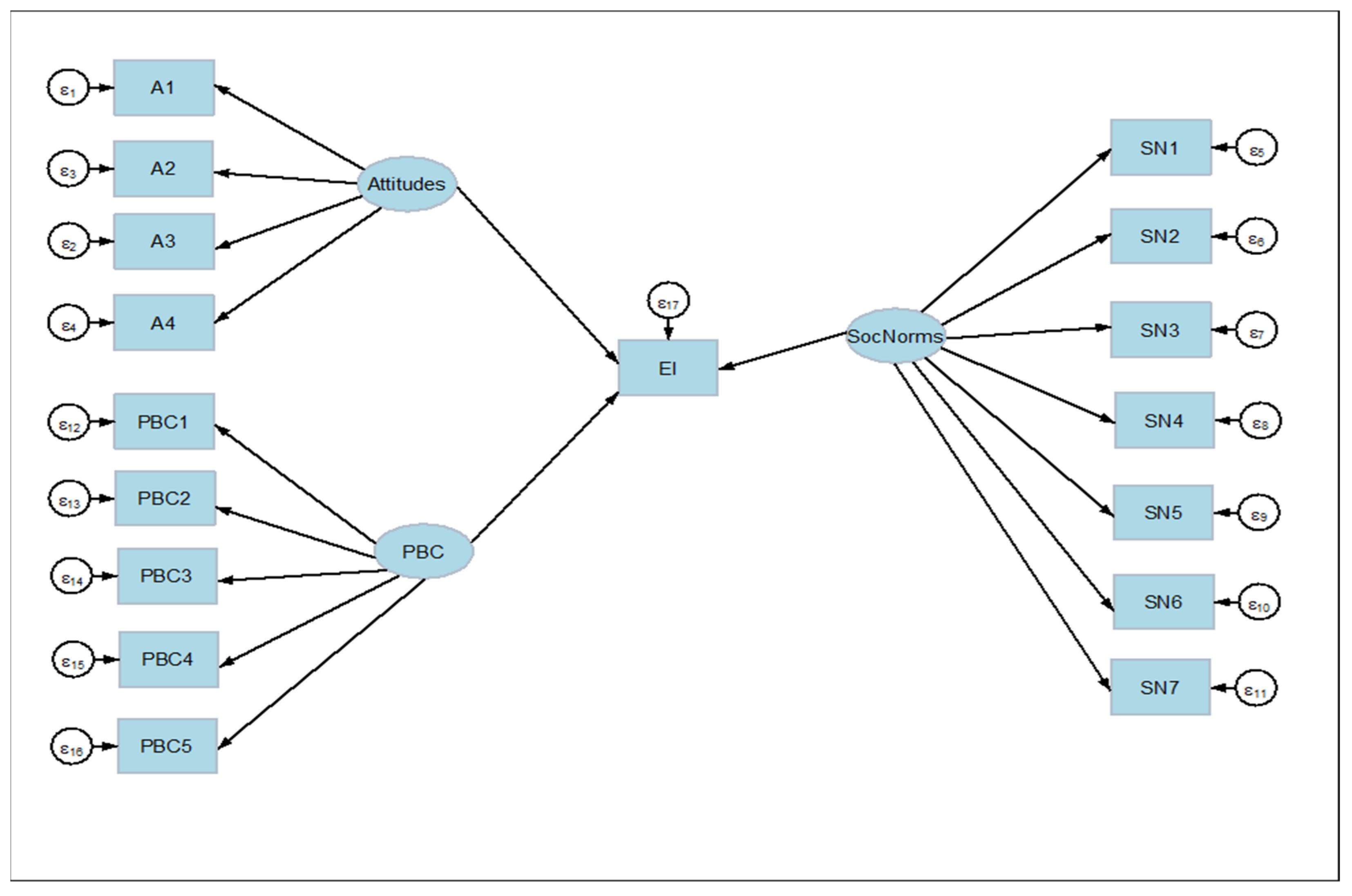

The SEM general diagram designed according to the above-formulated hypotheses is presented in

Figure 2.

4. Results

Using STATA 18.0, structural equation modeling was applied to the proposed research framework. SEM is useful in proving that the measurement model is accurate and reliable, and it enables theoretical connections between the variables of the structural model [

127].

In order to check the data distribution and reliability of the study constructs, we have further calculated the mean, standard deviation, and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients (

Table 3).

Overall, for most variables, the mean scores decreased from 2018 to 2023, reflecting a possible reduction in the measured constructs over time. In general, variability remains consistent or shows a slight decrease, with similar or slightly more uniform responses in 2023. All Cronbach’s alpha coefficients surpassed the 0.7 threshold value [

123], underlining a satisfactory level of internal consistency for both lots (2018 and 2023).

To evaluate the accuracy of the structural equation models, we conducted several robustness tests (

Table 4). In the goodness-of-fit test, the comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) present a value close to 1 for both analyzed periods, meaning that the model has a proper degree of fit. The coefficient of determination (CD) indicates that in over 99.2% of cases and 99.9% of cases, respectively, the proposed observed variables influence the latent variables.

Next, we assessed the measurement models’ convergent and discriminant validity. Convergent validity refers to how an item correlates positively with alternative items of the same construct. The items of a specific construct should converge, which means they share a high proportion of variance [

123]. Discriminant validity refers to the extent to which the absolute value of the correlation between two constructs is distinct from one another [

128]. Thus, we have generated average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), maximum shared variance (MSV), and maximum H reliability (maxr(H)) (

Table 5).

All CR and MaxR (H) values exceeded the 0.7 threshold, and all AVE values exceeded 0.5, ranging from 0.5012 to 0.6803, appropriate for the model fit. The MaxR(H) values were higher than the CR values, and the MSV values were lower than the AVE values. Therefore, both convergent and discriminant validity conditions are satisfied.

In order to test the discriminant validity between constructs, we next applied heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio analysis for both cohorts (

Table 6 and

Table 7).

If the HTMT ratio exceeds 0.85 [

129], the model shows a lack of discriminant validity. As indicated in

Table 6 and

Table 7, the HTMT values for all latent constructs in both lots are less than the 0.85 cut-off value. Hence, discriminant validity among the constructs is demonstrated, meaning that the latent variables are distinct from each other.

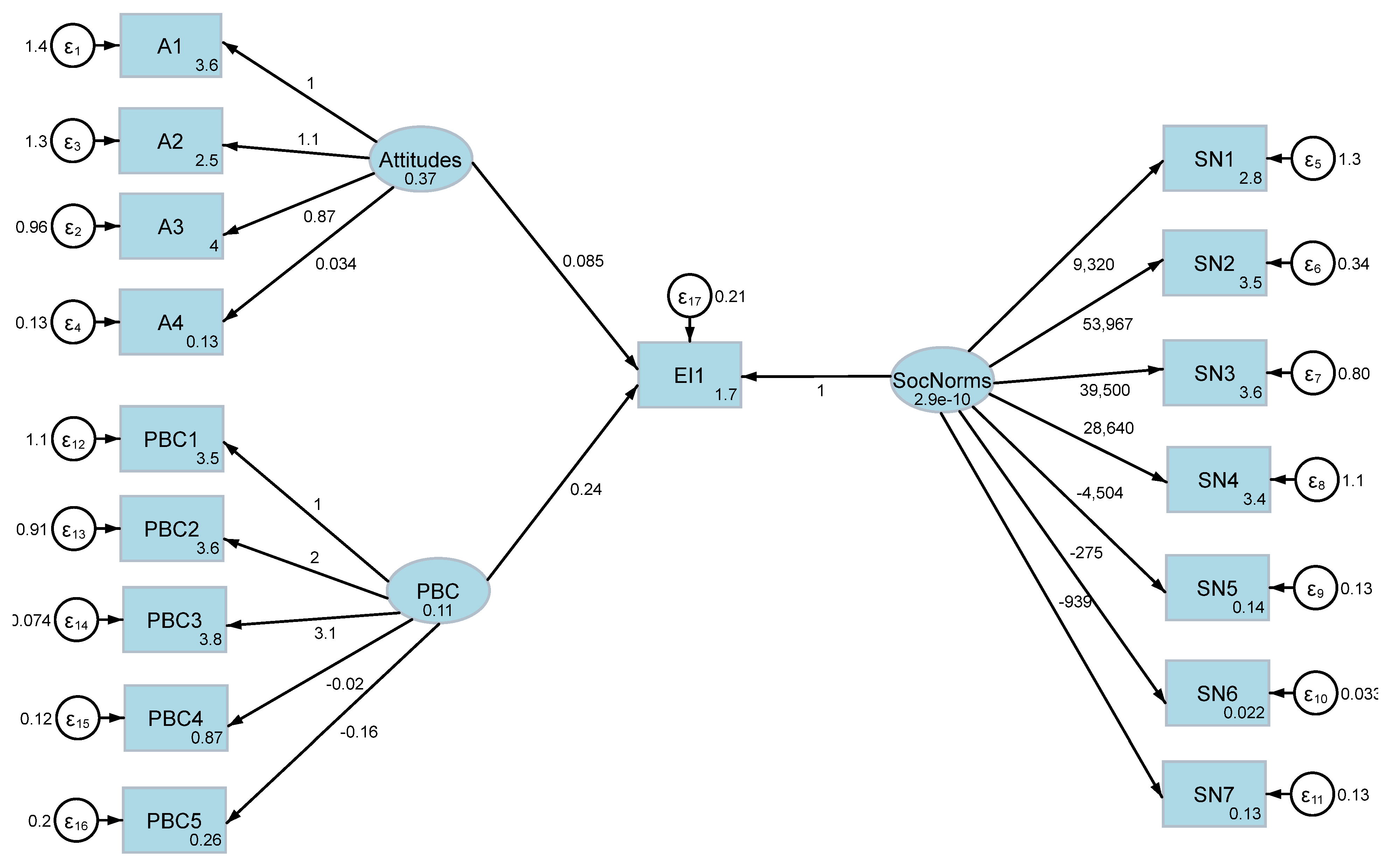

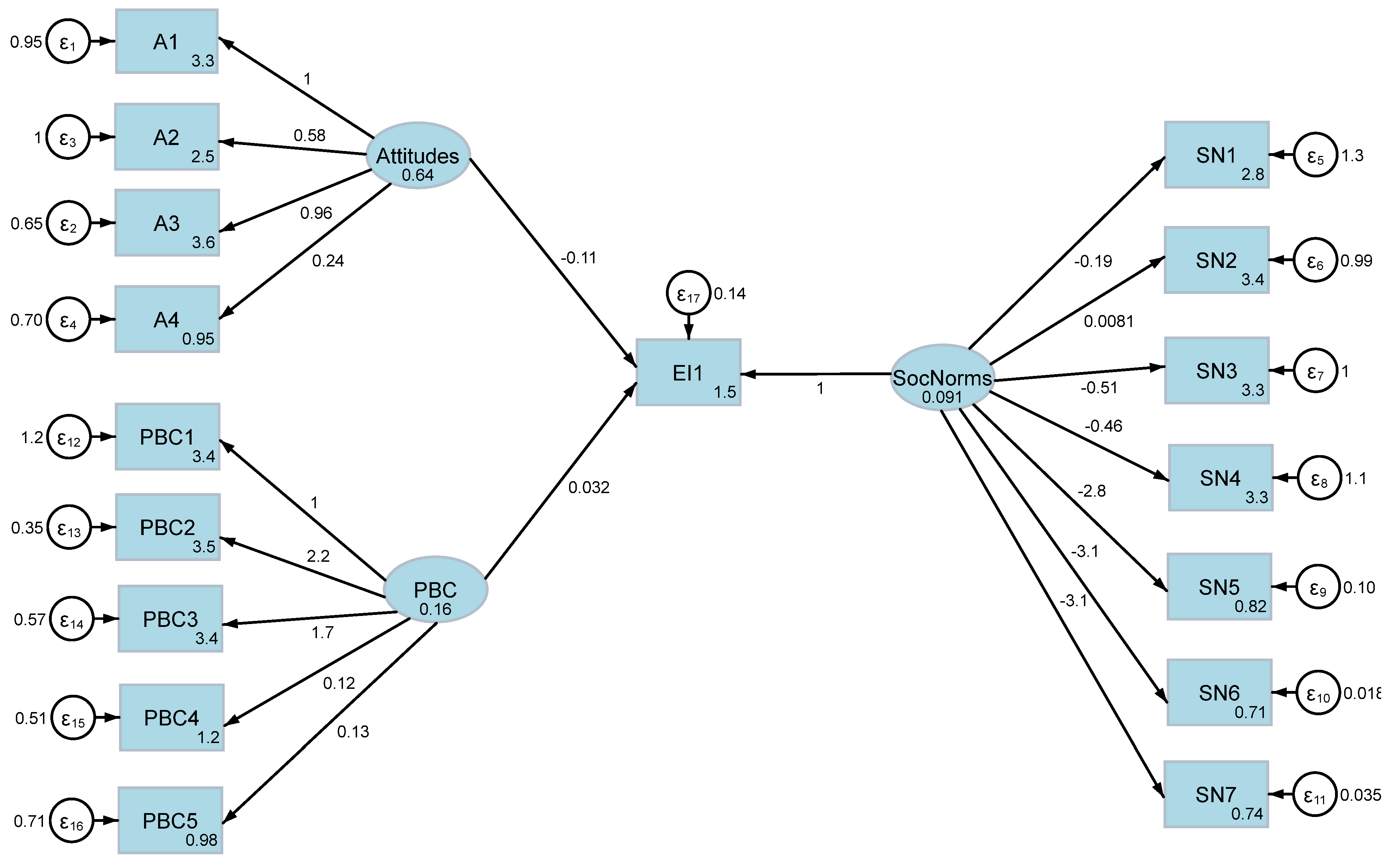

Afterwards, the SEM model was generated using the maximum likelihood estimator (MLE) method in Stata (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

For our study, the attitudes (as a latent variable) were considered on four dimensions: lack of business idea (coefficient 1 for both lots, the most decisive perceived disadvantage for 2023 lot), lack of partners (coefficient 1.1 in 2018, 0.58 in 2023, the most decisive perceived disadvantage for 2018 lot), lack of resources (coefficient 0.87 in 2018, 0.96 in 2023), and professional and personal recognition (coefficient 0.034 in 2018, 0.24 in 2023, the least relevant perceived disadvantage for both lots).

The perceived behavioral control targeted five directions: lack of entrepreneurial knowledge (coefficient 1 for both lots), difficult access to loans (coefficient 2 in 2018, 2.2 in 2023, with the most relevant for 2023), difficult access to grants (coefficient 3.1 for 2018, 1.7 for 2023, with the most relevant for 2018), independence (coefficient −0.02 for 2018, 0.12 for 2023, less relevant indicator for both lots), and larger gains (coefficient −0.16 for 2018, 0.13 for 2023).

The social norms were considered from seven perspectives: lack of diploma, unfavorable economic environment (the most decisive perceived disadvantage in 2018), unfavorable laws, lack of network, valorized market opportunities, the lack of a job, and taking over the family business (the most relevant perceived disadvantage, along with the lack of a job for 2023).

Based on the statistical analysis, for the 2018 lot, our SEM results show the following:

Attitudes (coef. = 0.085, p < 0.001) positively shape the entrepreneurial intention of the students. Out of the variables used for attitudes, the most relevant are lack of partners and lack of resources;

PBC (coef. = 0.24, p < 0.05) has a positive influence on the respondents’ entrepreneurial intention, specifically in the case of difficult access to loans and grants;

For SocNorms, there is a poor statistical significance; none of the metrics significantly represent this construct, indicating poor measurement.

In this model, “attitudes” appears to be the most significant predictor of entrepreneurial intent, with a statistically significant positive influence. “Perceived behavior control” also shows some potential influence, although it falls slightly short of conventional statistical significance, meaning that the difficult access to loans and grants can motivate individuals to pursue entrepreneurial activities, even if these conditions are challenging. “Social norms” does not appear to have a significant impact on entrepreneurial intent in our analysis.

As for the 2023 lot, our SEM results show that attitudes reversely shape the entrepreneurial intention of students (coef. = −0.11, p < 0.001). The identified relevant factors are a lack of partners and resources, exacerbated by the challenges posed by the pandemic. For this group experiencing exposure to isolation, unemployment, and a lack of resources, the post-COVID-19 environment has cultivated a mindset of innovation and perseverance, prompting individuals to adapt, push through challenges, and develop resilience and creativity. Thus, in light of issues related to unemployment, resource scarcity, etc., entrepreneurship became a viable solution, most often in basic areas of the economy (food and services) that do not require large investments and/or advanced knowledge. Additionally, the lack of resources and partners has led to a heightened awareness of unmet market needs. The pandemic forced many to rethink traditional career paths, which illustrates the complex nature of how attitudes can reflect both enthusiasm and hesitation in entrepreneurial contexts.

The SEM estimation results show that perceived behavioral control is a significant positive predictor (coef. = 0.032, p < 0.05) of the respondents’ entrepreneurial intention. The most relevant variables are difficult access to loans and difficult access to grants.

The results underline a strong positive correlation between social norms and the respondents’ entrepreneurial intention (coef. = 1, p < 0.005). The most relevant elements of social norms with an impact on students’ entrepreneurial intention are valorized market opportunities, lack of job, and taking over the family business.

Therefore, in our model for the post-COVID group, “attitudes” is the most significant predictor of entrepreneurial intent, with a statistically significant negative influence. “Perceived behavior control” shows a positive influence, meaning that difficult access to loans and grants can motivate individuals to pursue entrepreneurial activities, even if these conditions are challenging. “Social norms” also represents a positive predictor of the respondents’ entrepreneurial intention. This suggests that poor market opportunities, lack of job, and the opportunity to take over the family business can boost the entrepreneurial intention of students, even in challenging environmental factors.

Therefore,

Table 8 below reflects a synthesis of research hypothesis testing with the corresponding path coefficient,

p-value, and support status.

Regarding Hypothesis H4, the SEM estimations for both groups indicate that students’ entrepreneurial intention shows a similar trend before and after the COVID-19 pandemic, although the propensity towards entrepreneurship is stronger for the post-COVID-19 group, so Hypothesis H4 is partially validated (

Table 8).

In summary, this analysis suggests several key findings for our study. Difficult access to loans and grants can motivate individuals to pursue entrepreneurial activities, even if these conditions are challenging. Also, poor market opportunities, lack of jobs, and the opportunity to take over the family business can boost the entrepreneurial intention of students, even if these represent challenging and uncertain environmental factors. For both groups, “attitudes” appears to be the most significant predictor of entrepreneurial intent.

5. Discussion

Based on the relevant literature findings, the study hypothesized that attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control are relevant for the entrepreneurial intent of students, regardless of the COVID-19 pandemic, with a stronger propensity towards entrepreneurship for the post-COVID-19 group.

The results show that attitudes have a strong positive impact on students’ entrepreneurial intent for the pre-COVID-19 group, while “attitudes” is the most significant predictor of entrepreneurial intent, with a statistically significant negative influence for the post-COVID-19 group. For the latter group, the pertinent factors identified include a deficiency in partnerships and resources, further aggravated by the challenges posed by the pandemic. This group, facing isolation, unemployment, and a scarcity of resources, has experienced a post-COVID-19 environment that fosters a mindset characterized by innovation and resilience. Consequently, individuals have been motivated to adapt and confront obstacles, cultivating their creativity and perseverance. In response to issues such as unemployment and resource limitations, entrepreneurship has emerged as a feasible solution, predominantly manifesting in fundamental sectors of the economy (such as food and services) that require minimal investments and/or specialized knowledge. Furthermore, the scarcity of resources and partners has heightened the awareness of unmet market demands. The pandemic compelled many individuals to reconsider conventional career trajectories, highlighting the intricate nature of how attitudes toward entrepreneurship may embody both enthusiasm and ambivalence.

Overall, results suggest a noteworthy shift in the role of attitudes in influencing entrepreneurial intent post-pandemic, possibly indicating changing perspectives or priorities among students as did similar studies, like Gomes et al. [

57] and Agu et al. [

76]. On the other hand, there are studies [

52,

79] indicating that no direct relationship can be established between attitude and an individual’s desire to become an entrepreneur, with the lack of entrepreneurial experience being the main explanation.

Perceived behavioral control, particularly as it relates to entrepreneurial intentions, has exhibited varying impacts on different student cohorts, specifically distinguishing between the pre-COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 periods. In the pre-COVID-19 context, factors defining PBC—such as lack of entrepreneurial knowledge, difficulties in accessing loans and grants, the desire for independence, and the pursuit of larger gains—demonstrated a possible influence on students’ entrepreneurial intentions; however, this influence may have been statistically less significant depending on individual circumstances. This could be attributed to the relative stability of the pre-pandemic economic environment, where entrepreneurial opportunities were more accessible, thus limiting the perceived barriers faced by students seeking to enter entrepreneurial ventures, as demonstrated by similar studies [

70,

80,

81,

87,

93].

The post-COVID-19 group showed a significant positive correlation between PBC and EI. This change can be largely attributed to the pandemic-induced economic realities that reshaped students’ perspectives on entrepreneurship. The pandemic intensified the awareness of market needs as traditional employment opportunities dwindled, thereby catalyzing students’ recognition of entrepreneurship as an attractive career option [

1]. Studies have suggested that during crises, such as the one triggered by COVID-19, students may experience an increase in entrepreneurial motivation spurred by necessity and the urgent need for innovative solutions to new challenges [

130]. This implies that perceived behavioral control can act as a robust predictor of EI, particularly under circumstances that necessitate adaptive thinking and proactive career choices.

Furthermore, the literature indicates that a foundational understanding of entrepreneurship and increased confidence in navigating financial barriers—which comprise the components of PBC—significantly bolster entrepreneurial intentions among students in dynamic contexts, such as those created during and post-pandemic [

52]. Thus, while the pre-COVID-19 landscape may have showcased a moderate impact of PBC on entrepreneurial intentions, the pandemic has catalyzed a paradigm shift, highlighting PBC as a critical lever driving the entrepreneurial aspirations of the post-COVID-19 student demographic.

As for social norms, our results highlight a strong positive impact on students’ entrepreneurial intent for the post-COVID-19 group, while not relevant for the pre-COVID-19 group. This emphasizes the enduring influence of social norms on entrepreneurial intent, with heightened relevance post-pandemic, as did similar studies like Zhang et al. [

79], Raza et al. [

48], and Botezat et al. [

22]. However, referring to social norms, our results are inconsistent with the studies of Maresch et al. [

84], Iglesias-Sanchez et al. [

78], and Čačija et al. [

27], where social norms do not represent a determining component of entrepreneurial intent. This inconsistency may reflect various contextual factors, including the specific demographics of study participants, differences in methodologies employed, or the degree of economic and social turmoil experienced during their respective research periods.

Our results could be explained when delving deeper into the specific variables that constitute social norms, as these variables reflect the socio-economic context in which students operate and help explain the observed heightened significance of social norms in the post-COVID-19 group. Social capital is a critical determinant of entrepreneurial success. The absence of robust networking opportunities can create social norms that discourage entrepreneurial intent, especially in times of uncertainty. Furthermore, the perception that conventional employment is unstable can compel students to view entrepreneurship in a more favorable light. The pandemic has altered perceptions of job security, making self-employment and entrepreneurial ventures appear as viable alternatives to traditional job routes.

The post-pandemic landscape has recalibrated students’ perceptions of entrepreneurial endeavors. As societies adapt to new economic realities, individuals are increasingly influenced by the collective experiences and behaviors of their peers. The notion of social validation—understanding that entrepreneurship is not only a viable path but also a socially supported one—could explain the stronger correlation observed in our study. The pandemic may have cultivated a greater sense of community among aspiring entrepreneurs, thereby enhancing the impact of social norms on entrepreneurial intentions.

In order to examine the interplay of attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control based on the Theory of Planned Behavior approach, we have used in our constructs variables referring to entrepreneurial education. In addition, all of the students included in our study have studied at least one entrepreneurship course and have followed internships in various business organizations. For these variables, both groups consider entrepreneurial education a facilitator of entrepreneurial intent, highlighting the consistent role of entrepreneurial education in fostering entrepreneurial intent irrespective of the pandemic, as underlined by similar studies in Romania [

11,

12,

23].

Another point of discussion relates to the fact that our study reveals significant shifts in the influence of TPB constructs on entrepreneurial intention among students before and after the COVID-19 pandemic, indicating that the socio-economic upheaval caused by the pandemic recalibrated the relative importance of these constructs. Notably, the findings demonstrate a robust positive impact of perceived behavioral control on entrepreneurial intent in the post-COVID-19 group, in contrast to a more moderate influence observed pre-pandemic. This shift suggests that conditions of crisis can fundamentally alter how individuals perceive their ability to engage in entrepreneurial activities. The economic realities experienced due to the pandemic heightened students’ recognition of entrepreneurship as both a necessary and viable career path, challenging the traditional view that PBC exhibits a stable effect on entrepreneurial intentions across contexts.

Moreover, the change in attitudes observed—where positive attitudes significantly predicted EI pre-pandemic but demonstrated a negative influence post-pandemic—highlights an important extension of TPB. This shift points toward a more ambivalent relationship with entrepreneurship, where external pressures, such as resource limitations and unemployment, can simultaneously fuel a desire for entrepreneurship while inducing an underlying doubt about its feasibility. Thus, our results indicate that the dimensions of the TPB may not remain consistent across different socio-economic landscapes, as suggested by previous literature [

3,

130].

Overall, our study indicates that the inclination towards entrepreneurship is more pronounced in the post-COVID-19 cohort, highlighting a significant disparity in entrepreneurial tendencies between the two groups, which may be shaped by the pandemic’s effects on perceptions and career decisions, as demonstrated by similar studies [

22,

23].

6. Conclusions

Amongst the impact of the global COVID-19 pandemic, a notable development has been entrepreneurship disruptions and challenges for current and future businesses. This has prompted a surge of research aimed at understanding the phenomenon, including the influence on entrepreneurial intentions among students in various countries across the globe. In this context, a particular focus should be on re-evaluating the factors influencing entrepreneurial intentions. As educational institutions and policymakers navigate this landscape, understanding these dynamics is essential for fostering a resilient entrepreneurial spirit among the youth.

Thus, with the Theory of Planned Behavior as a foundation approach, our study sought to develop a thorough framework for comprehending the psychological factors influencing entrepreneurial intent. Our study addresses a research gap by exploring the impact of the global COVID-19 pandemic on Romanian students’ entrepreneurial intentions, utilizing a comparative analysis of relevant cohorts before and after the pandemic, being one of the few longitudinal studies nationwide.

While the study is geographically limited (a single university in Romania) and the sample is gender imbalanced (with more women than men) and limited in professional experience (only 28% of respondents are employed/entrepreneurs), the results can be generalized at least for the Romanian landscape. The notable gender imbalance reflects a broader national trend, as women often represent a significant portion of the university population in Romania (over 50%). Thus, while our findings may be more representative of this particular sample, they can nonetheless contribute to understanding entrepreneurial intent among Romanian students as a whole. Students come from different regions of the country with a pattern of high in-country mobility in terms of university studies and even though most of them have no professional experience, they participated in mandatory internships in various businesses (as part of their curriculum).

According to the 2023 Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) country report [

16], the rate of early-stage entrepreneurial activity in Romania stands at 8.25%, slightly below the 12.94% average of 51 participating countries. Also, 47.2% of early-stage entrepreneurs have university studies. Analyzing data from Romania, we observe that people with higher education are more likely to become entrepreneurs. This category also stands out among potential entrepreneurs (56.4%).

Recent surveys highlight the growing importance of women in entrepreneurship. According to GEM (2023) [

16], more and more women are choosing this career path. Cardella et al. [

131] point out that women are the fastest-growing category of entrepreneurs. However, these trends are not found in Romania, as men dominate all entrepreneurial categories, and the gender gap is significant. Only 1 in 15 women in Romania intends to start a business in the near future compared to 1 in 10 men. This emphasizes the need for designing educational interventions to effectively engage both men and women in entrepreneurial activities.

Although our study sample is unique, the underlying psychological variables associated with entrepreneurial intention—such as attitudes, perceived behavioral control, and social norms—can be applied to other educational and cultural contexts. Researchers in different regions could utilize our findings as a baseline to analyze how these factors may differ in their own cohorts, particularly as they incorporate varying gender ratios and professional experiences into their studies.

Moreover, our study’s findings may lay a foundation for understanding how external factors, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, shape entrepreneurial intentions among students. Future researchers can generalize some aspects of our findings to different geographical regions and educational contexts by investigating how similar socio-economic conditions and educational pathways affect entrepreneurial intent.

In terms of entrepreneurial education, particularly following disruptions like the COVID-19 pandemic, it is imperative for universities to revise their entrepreneurial education curriculums. Fostering adaptability and crisis management in business planning should become a cornerstone of these programs. Curricula should include modules that teach students how to modify business plans in response to changing market conditions and emerging crises, as well as case studies of businesses that successfully pivoted during economic downturns, demonstrating real-world applications of theoretical concepts. Another approach could be specialized courses focused on crisis management strategies within entrepreneurship education that cover risk assessment, contingency planning, and strategic decision-making to equip students with tools to navigate potential threats to business continuity. Furthermore, opportunities for experiential learning, such as internships, mentorship programs, and involvement in startup ecosystems, should be taken into account. Engaging industry experts in curriculum design can help ensure that educational programs remain aligned with real-world needs and challenges.

Ensuring that students are equipped with the requisite entrepreneurial skills necessary for navigating a complex and evolving economy could be realized by expanding entrepreneurship education programs beyond traditional economics and business faculties. Complementary universities should collaborate in designing and implementing interdisciplinary entrepreneurship courses that integrate perspectives from fields such as engineering, arts, humanities, social sciences, and STEM disciplines. Thus, students can gain a diverse skill set and innovate within various sectors.

In terms of academic implications, we strive to provide contributions to the specific broader academic literature. Our findings underlined the dynamic weight of attitudes, social norms, and PBC, contributing to the broader understanding of the TPB by demonstrating that its dimensions may shift in relevance and strength based on the socio-economic crisis context. This highlights the opportunity for a re-evaluation of how the TPB is applied in rapidly changing environments, suggesting that its constructs are not only interrelated but also inherently dynamic, influenced by the surrounding economic and social landscapes.

However, it is important to acknowledge certain potential limitations of our study. As the study exclusively focused on students from a single university in Romania, the results cannot be generalized, as previously highlighted. The geographical and cultural specificity may limit the applicability of our results to other contexts or demographics. Moreover, regional variations can significantly impact entrepreneurial intentions due to differing socio-economic conditions, cultural values, and educational frameworks.

Also, the limitations of self-reported data warrant consideration. As respondents were asked to share their perceptions and intentions, biases such as social desirability or recall bias could have influenced the accuracy of the responses collected. This is particularly relevant in studies of entrepreneurial intention, where respondents may overstate their aspirations due to the perceived social value associated with entrepreneurship [

132]. Such biases can confound the validity of the findings, making it essential to interpret the results with caution.

In addition, our results are consistent within the model and variables used but, as highlighted previously, there are a number of various models and variables used for such an analysis, which could lead to additional conclusions on the topic.

Nonetheless, further research and exploration of additional variables may be needed to better understand the determinants of entrepreneurial intent in this particular context. Incorporating contextual variables such as perceptions of risk, uncertainty, digitalization, and social capital will deepen our understanding of the entrepreneurial landscape and contribute to more effective educational strategies aimed at fostering entrepreneurial ambition among students.

The outcomes might differ if students from different Romanian universities were included in the survey. Broadening the sample of students could also be a possible a future research path. Moreover, it would be interesting to conduct research on students in other Eastern Europe countries, as these are countries that share a similar history, economy, culture, and educational background.

Another potential avenue for further research is employing mixed methods, such as qualitative interviews or focus groups, which could yield richer insights into the motivations behind entrepreneurial shifts. By gathering qualitative data, the nuanced factors affecting students’ entrepreneurial choices can be explored, beyond what quantitative measures can capture. Future studies could include structured interviews with participants who have experienced transitions in their entrepreneurial intentions for an in-depth understanding of their underlying motivations and external influences. This could be linked with further investigations of actual entrepreneurial behavior in alumni. A longitudinal study that tracks students from various cohorts could be designed, to monitor their entrepreneurial activities over time. By comparing their self-reported intentions with their real-world behaviors, the effectiveness of intention models and the influence of educational interventions could be better assessed.

The rise of digital entrepreneurship and the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) represent other possible venues for future research. Incorporating these elements can significantly enhance the understanding of how technology influences entrepreneurial intentions and behaviors, especially in a post-pandemic context, hence the current research trend’s focus on them [

133].

In light of the unforeseen disruptions caused by the global COVID-19 pandemic, our findings underscore a significant need for a cross-cultural comparative approach to understanding entrepreneurial intentions across varying socio-economic landscapes. This approach is especially pertinent as we analyze the factors that have shifted due to the pandemic’s impact on business environments. Our study, while focused on Romanian students, serves as a valuable case study within a larger body of the literature addressing entrepreneurial intentions across diverse cultural contexts [

99]. Integrating insights from cross-cultural comparative studies can enrich our understanding of how different socio-economic and cultural dynamics shape entrepreneurial behavior. For instance, research by Ye and Dong [

134] emphasizes the role of cross-cultural adaptation on entrepreneurs’ psychology and intentions. Their study reveals that entrepreneurs in varying cultural settings respond differently to challenges and opportunities, suggesting that the psychological factors influencing entrepreneurial intent can be deeply contextualized, as did other relevant studies [

9,

135]. This means that our findings about Romanian students can be compared with those of entrepreneurs in other cultural settings, thereby illuminating how cultural values and norms drive different entrepreneurial outcomes.

While the pandemic has presented significant challenges in all fields around the globe, it has also catalyzed innovation and adaptability among entrepreneurs, highlighting the resilience of the entrepreneurial spirit in times of adversity, both challenging and transforming entrepreneurial intentions among students. Continued empirical research will be vital in refining our understanding of this phenomenon and thus tailoring entrepreneurial education accordingly.