Effect of Community Place Qualities on Place Value in a Destination

Abstract

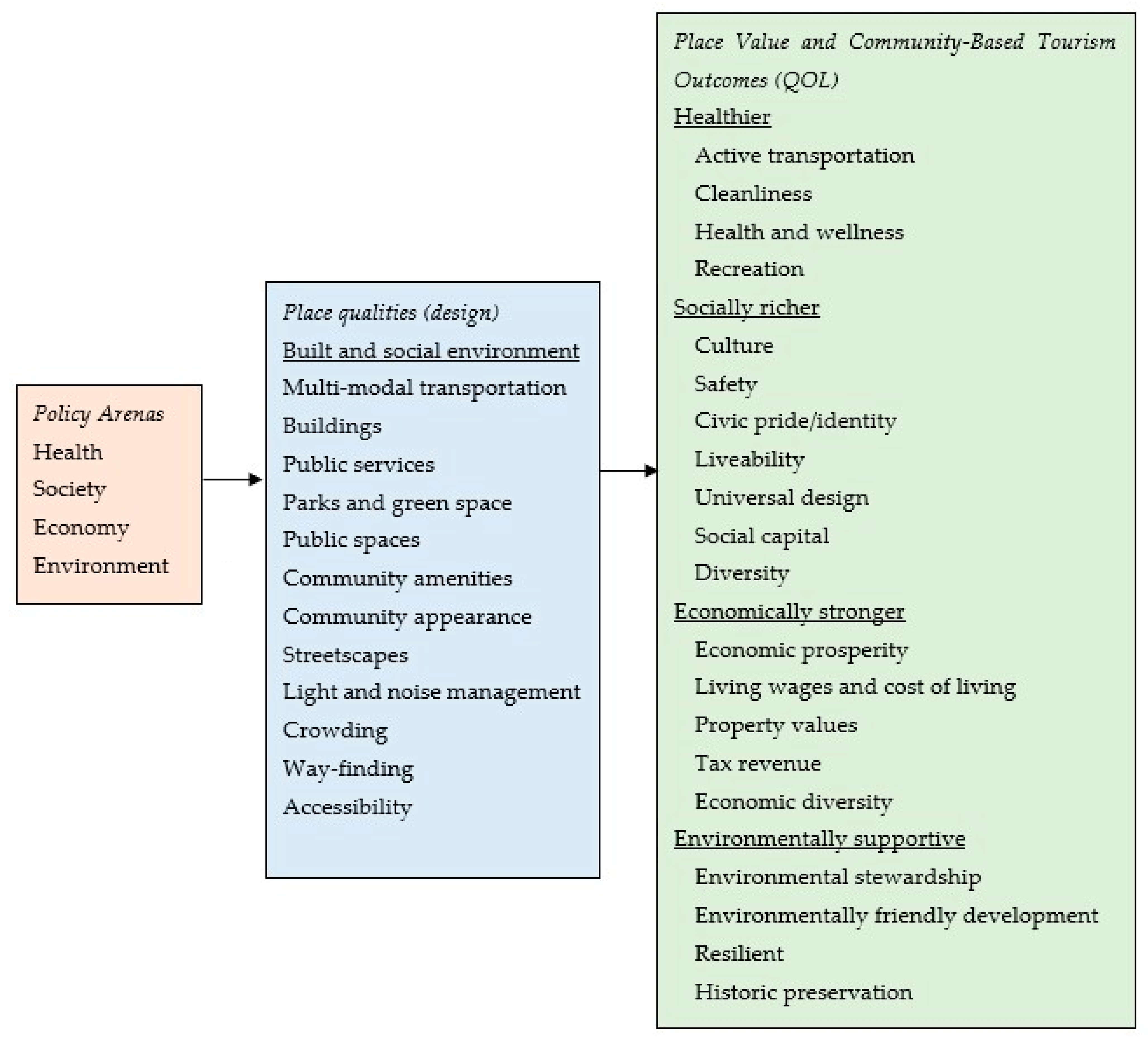

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Design in Tourism

2.2. Quality of Life and Tourism

2.3. Design, QOL, Place Qualities, and Place Value

2.4. Purpose, Proposition, and Hypothesis

3. Methods

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

3.2. Measurement and Analysis

4. Findings

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications for Designing Tourism Places

5.2. Implications for Theory Development

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xiang, Z.; Stienmetz, J.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Smart tourism design: Launching the Annals of Tourism Research curated collection on designment tourism places. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 86, 103154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesenmaier, D.R.; Xiang, Z. Introduction to tourism design and design science in tourism. In Design Science in Tourism: Foundations of Destination Management; Fesenmaier, D.R., Xiang, Z., Eds.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2017; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Tussyadiah, I.P. Toward a theoretical foundation for experience design in tourism. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 543–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, C.A.; Andereck, K.L.; Pham, K. Designing for quality of life and sustainability. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Berbekova, A.; Wang, J. Quality of life: A critical examination of research progress. Tour. Manag. 2025, 107, 106070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liburd, J.; Duedahl, E.; Heape, C. Co-designing tourism for sustainable development. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 2298–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, K.; Vogt, C.A.; Andereck, K.L. Overtourism: A Potential Outcome in Contemporary Tourism—Concepts, Indicators, and Impacts. In Sustainable Development and Resilience of Tourism: Wellbeing and Quality of Life Perspectives; Chhabra, D., Atal, N., Maheshwari, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 165–186. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. ‘Overtourism’? Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth Beyond Perceptions; United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Banyón, A.; Daumann, F. European tourism sustainability and the tourismaphobia paradox: The case of the Canary Islands. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuttari, S.; Pechlaner, H.; Erschbamer, G. Destination design: A heuristic case study approach to sustainability-oriented innovation. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 86, 103068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volgger, M.; Cheer, J.; Pforr, C. Evidence-informed decision-making in sustainable tourism: From research to action. J. Sustain. Tour. 2025, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koens, K.; Smit, B.; Melissen, F. Designing destinations for good: Using design road mapping to support pro-active destination development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 89, 103233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Jiang, J.; Li, S. A sustainable tourism policy research review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. Place value: Place quality and its impact on health, social, economic and environmental outcomes. J. Urban Des. 2019, 24, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stienmetz, J.; Kim, J.J.; Xiang, Z.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Managing the structure of tourism experiences: Foundations for tourism design. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zach, F.J.; Xiang, Z. Design standardization by Airbnb multi-unit hosts: Professionalization in the sharing economy. Ann. Tour. Res. 2023, 98, 103523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Berbekova, A.; Kim, H. Designing for quality of life. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volgger, M.; Erschbamer, G.; Pechlaner, H. Destination design: New perspectives for tourism destination development. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Tourism experience and tourism design. In Design Science in Tourism; Fesenmaier, D.R., Xiang, Z., Eds.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2017; pp. 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Andereck, K.L.; Nyaupane, G.P. Exploring the nature of tourism and quality of life perceptions among residents. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Li, G.; Liu, A.; Chen, J.L. Emerging research trends on residents’ quality of life in the context of tourism development. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2024, 48, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. Quality-of-life indicators as performance measures. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 76, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Cole, S.T.; Chancellor, C. Resident support for tourism development in rural midwestern (USA) communities: Perceived tourism impacts and community quality of life perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents? Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J.; Woo, E.; Kim, H. Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, I.; Raphael, D.; Renwick, R. Quality of Life Profile. Item 2; Quality of Life Research Unit, Center for Health Promotion, University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, USA, 1998; pp. 78–136. [Google Scholar]

- Massam, B.H. Quality of life: Public planning and private living. Prog. Plan. 2002, 58, 141–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, E.J.; Vieira, J.C.; Santos, C.M.; Huang, T.Y. Do residents differentiate between the impacts of tourism, cruise tourism, and Airbnb tourism? In Methodological Advancements in Social Impacts of Tourism Research; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2023; pp. 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Z.X.; Hui, T.K. Residents’ quality of life and attitudes toward tourism development in China. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, E.; Khalifah, Z.; Mardani, A.; Streimikiene, D.; Han, H. Community attachment, tourism impacts, quality of life and residents’ support for sustainable tourism development. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 1061–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, V. Why local residents support sustainable tourism development? J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 877–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, E.J.; Spencer, D.M.; Prayag, G. Tourism impacts, emotions and stress. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, E.J.; Lesar, L.; Spencer, D.M. Clarifying the interrelations of residents’ perceived tourism-related stress, stressors, and impacts. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, E.J.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ perceptions of stress related to cruise tourism development. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2017, 14, 527–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, P.V.; Sreejesh, S. Impact of responsible tourism on destination sustainability and quality of life of community in tourism destinations. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 31, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Huang, S.; Huang, J. Effects of destinations social responsibility and tourism impacts on residents’ support for tourism and perceive quality of life. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 42, 1039–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Kim, J.; Gibson, H.J.; Thapa, B. The impact of resilience on community variations in the relationships between tourism and quality of life. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2024, 33, 100928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalic, T.; Kuscer, K. Can overtourism be managed? Destination management factors affecting residents’ irritation and quality of life. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Li, Y. Understanding impacts of neighbourhood micro-renewal through a lens of place value: A case study of Wuhan, China. Land 2024, 13, 1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. Public Places Urban Spaces, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Erol, Z.Ç.; Ciravoğlu, A. The social dimensions of place and place quality indicators in urban space. Int. J. Built Environ. Sustain. 2025, 12, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lak, A.; Sharifi, A.; Khazaei, M.; Aghamolaei, R. Towards a framework for driving sustainable urban regeneration with ecosystem services. Land Use Policy 2021, 111, 105736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, M. Quality of Place BT. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 5312–5314. [Google Scholar]

- Delpino-Chamy, M.; Pérez Albert, Y. Assessment of citizens’ perception of the built environment throughout digital platforms: A scoping review. Urban Sci. 2022, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navickas, V.; Skripkiūnas, T.; Tanas, J.; Trojanek, M. The influence of architecture on real estate market value: A methodological framework. J. Int. Stud. 2020, 13, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M.; Magalhães, C.D.; Edwards, M. What value urban design? Urban Des. Int. 2002, 7, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Census Bureau. U.S. Census. Available online: https://www.census.gov (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Arizona Commerce Authority. Community Profiled. Available online: https://www.azcommerce.com/a/profiles/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Peeters, P.; Gössling, S.; Klijs, J.; Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Dijkmans, C.; Eijgelaar, E.; Hartman, S.; Heslinga, J.; Isaac, R.; et al. Research for TRAN Committee—Overtourism: Impact and Possible Policy Responses; European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman, D.A. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, F.; Berbekova, A.; Assaf, A.G. Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: Detection, prevention and control. Tour. Manag. 2021, 86, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleininger, H. Mountain or molehill? A simulation study on the impact of response styles. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2016, 77, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupré, S.; Heyde, F.; Vergauwe, J.; Wille, B. Too little, just right or too much? Assessing how people evaluate their conscientiousness levels. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2022, 197, 111789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergauwe, J.; Wille, B.; Hofmans, J.; Kaiser, R.B.; Fruyt, F.D. The too little/too much scale: A new rating format for detecting curvilinear effects. Organ. Res. Methods 2017, 20, 518–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.R.; Aguinis, H. The too-much-of-a-good-thing effect in management. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 313–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiStefano, C.; Shi, D.; Morgan, G.B. Collapsing categories is often more advantageous than modeling sparse data: Investigations in the CFA framework. Struct. Equ. Model. 2021, 28, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4th ed.; Sage Publications Limited: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman, A. Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. JEM 2009, 45, 94. [Google Scholar]

- Renwick, R.; Brown, L. The Center for health promotion’s conceptual approach to quality of life: Being, belonging and becoming. In Quality of Life in Health Promotion and Rehabilitation; Renwick, R., Brown, L., Naggler, M., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Inglehart, R.; Tay, L. Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 112, 497–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabra, C.; Almeida, S.; Reis, M. Quality-of-Life perception among young residents and visitors: The impact of COVID-19. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suntikul, W.; Pratt, S.; Kuan, W.I.; Wong, C.I.; Chan, C.C.; Choi, W.L.; Chong, O.F. Impacts of tourism on the quality of life of local residents in Hue, Vietnam. Anatolia 2016, 27, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Nyaupane, G.P.; Andereck, T.K. Exploring the differences between educational and escapist experience stagers: A multi-perspective approach. Tour. Rev. Int. 2015, 19, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, I. Extreme response style in cross-cultural research: An empirical investigation. J. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2000, 15, 137–152. [Google Scholar]

| Demographics | Percentages |

|---|---|

| Gender | 48% male, 52% female |

| Age | Mean: 67 years old |

| Education | 44% advanced degree, 30% college degree, 26% below college or technical school |

| Residency | 74% full-time, 26% part-time |

| Average: 15 years of residency | |

| Household annual income | 52% over USD 100,000, 13% below USD 50,000, and |

| 35% in between | |

| Involvement in tourism | 82% not employed in tourism, 18% employed in tourism |

| Percent | Current Perception Mean a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community Features | Too Little | About Right | Too Much | |||

| Amount of traffic | 0.5 | 0.8 | 8.2 | 18.9 | 71.5 | 4.6 |

| Number of tourists | 0.08 | 1.6 | 29.4 | 23.2 | 45.0 | 4.1 |

| Noise | 0.8 | 2.2 | 51.8 | 26.2 | 19.0 | 3.6 |

| Lighting at night | 3.6 | 6.1 | 59.4 | 13.5 | 17.4 | 3.4 |

| Variety of attractions | 3.1 | 12.5 | 70.8 | 8.9 | 4.7 | 3.0 |

| Restaurants | 2.2 | 12.2 | 71.7 | 9.7 | 4.2 | 3.0 |

| Trails | 1.9 | 9.7 | 77.0 | 8.3 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Directional signs | 4.7 | 11.9 | 73.7 | 4.4 | 5.3 | 2.9 |

| Disability access | 4.1 | 13.8 | 76.8 | 4.7 | 0.6 | 2.8 |

| Built environment (buildings, parks, and transportation systems) | 7.8 | 25.0 | 54.4 | 9.7 | 3.1 | 2.8 |

| Parking lots | 16.5 | 30.2 | 47.5 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 2.5 |

| Roads | 18.0 | 23.0 | 54.5 | 2.8 | 1.7 | 2.5 |

| Public restrooms | 14.4 | 31.9 | 50.6 | 2.6 | 0.6 | 2.4 |

| Overall community walkability | 22.2 | 24.1 | 47.9 | 4.4 | 1.4 | 2.4 |

| Public transportation | 38.3 | 30.3 | 27.3 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 2.0 |

| Means | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QOL Indicators | Importance a | Satisfaction b | Composite Index c | Factor Loading |

| Community Environment (variance explained = 22.2%, alpha = 0.89, omega = 0.89, scale mean = 12.7) | ||||

| Attractiveness/cleanliness | 4.8 | 3.7 | 13.2 | 0.767 |

| Limited litter and vandalism | 4.8 | 3.7 | 13.5 | 0.748 |

| Safety/lack of crime | 4.8 | 4.0 | 15.0 | 0.748 |

| Public safety (police, fire, etc.) | 4.7 | 4.1 | 15.2 | 0.693 |

| Preservation of cultural/historic sites | 4.6 | 3.6 | 13.0 | 0.635 |

| Conservation of natural areas | 4.8 | 3.4 | 11.7 | 0.634 |

| Clean air and water | 4.8 | 3.5 | 12.5 | 0.603 |

| Peace and quiet | 4.7 | 3.2 | 10.8 | 0.561 |

| Authentic culture | 3.7 | 3.3 | 11.1 | 0.536 |

| Quality recreation opportunities | 4.2 | 3.6 | 12.5 | 0.469 |

| Community identity | 3.9 | 3.5 | 12.0 | 0.465 |

| Community Crowding (variance explained = 12.7%, alpha = 0.83, omega = 0.83, scale mean = 6.2) | ||||

| Crowding in other areas of town | 4.2 | 2.3 | 6.9 | 0.818 |

| Crowding of roads | 4.6 | 1.7 | 4.2 | 0.796 |

| Crowding in the uptown district | 3.8 | 2.1 | 6.2 | 0.773 |

| Crowding of trails | 4.2 | 2.5 | 8.0 | 0.711 |

| Community Diversity (variance explained = 9.5, alpha = 0.60, omega = 0.60, scale mean = 10.2) | ||||

| Diversity and quality of employment | 3.7 | 2.8 | 9.0 | 0.737 |

| Cultural activities for residents | 3.9 | 3.2 | 10.6 | 0.624 |

| Diverse economy | 3.6 | 2.8 | 9.0 | 0.567 |

| Community Economy (variance explained = 9.4%, alpha = 0.68, omega = 0.69, scale mean = 11.0) | ||||

| Fair prices of goods and services | 4.2 | 3.0 | 10.1 | 0.722 |

| Adequate tax revenues to support city services | 3.9 | 3.3 | 11.5 | 0.592 |

| High standard of living | 4.2 | 3.5 | 12.5 | 0.590 |

| Reasonable real estate costs | 3.5 | 3.1 | 10.2 | 0.558 |

| Tourist spending | 3.1 | 3.2 | 11.1 | 0.432 |

| Place Qualities (Independent Variables) | Place Value Dimensions (Dependent Variables) | Means | Univariates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Too Little | About Right | Too Much | F | p | ||

| Number of tourists | Environment | 13.9 | 13.8 | 12.2 | 12.8 | 0.00 |

| Crowding | 9.7 a | 8.3 a | 5.2 b | 45.3 | 0.00 | |

| Diversity | 11.3 a | 10.2 ab | 9.2 b | 5.3 | 0.01 | |

| Economy | 11.2 | 11.8 | 10.5 | 11.4 | 0.00 | |

| Model statistics: V = 0.23; F = 11.0; p = 0.00 | ||||||

| Amount of traffic | Environment | 14.8 | 13.7 | 12.6 | 3.2 | 0.04 |

| Crowding | 7.6 a | 10.0 b | 5.9 a | 23.5 | 0.00 | |

| Diversity | 10.5 | 11.1 | 9.4 | 4.5 | 0.01 | |

| Economy | 11.4 | 12.4 | 10.8 | 5.2 | 0.01 | |

| Model statistics: V = 0.14; F = 6.3; p = 0.00 | ||||||

| Noise | Environment | 15.0 a | 13.4 b | 11.7 c | 16.8 | 0.00 |

| Crowding | 8.2 a | 7.3 a | 5.0 b | 24.5 | 0.00 | |

| Diversity | 9.1 | 9.9 | 9.1 | 3.7 | 0.03 | |

| Economy | 12.1 a | 11.3 ab | 10.5 b | 5.4 | 0.01 | |

| Model statistics: V = 0.15; F = 7.1; p = 0.00 | ||||||

| Built environment | Environment | 12.6 a | 13.1 a | 11.5 b | 4.3 | 0.03 |

| Crowding | 6.2 a | 6.6 a | 4.8 b | 5.1 | 0.03 | |

| Diversity | 10.1 | 10.9 | 10.4 | 3.8 | 0.02 | |

| Economy | 9.1 | 9.8 | 9.0 | 2.5 | 0.01 | |

| Model statistics: V = 0.06; F = 2.4; p = 0.03 | ||||||

| Public transportation | Environment | 12.8 | 12.7 | 11.6 | 1.2 | 0.33 |

| Crowding | 6.4 a | 6.2 a | 4.0 b | 4.4 | 0.01 | |

| Diversity | 9.3 | 10.0 | 10.1 | 1.9 | 0.20 | |

| Economy | 10.5 | 10.9 | 11.1 | 0.4 | 0.65 | |

| Model statistics: V = 0.05; F = 2.3; p = 0.02 | ||||||

| Variety of attractions | Environment | 12.9 | 12.7 | 12.3 | 0.5 | 0.62 |

| Crowding | 6.1 | 6.4 | 5.4 | 1.7 | 0.18 | |

| Diversity | 8.3 a | 9.9 bc | 8.9 ab | 7.9 | 0.00 | |

| Economy | 10.5 | 11.2 | 10.3 | 3.5 | 0.03 | |

| Model statistics: V = 0.07; F = 3.2; p = 0.04 | ||||||

| Community walkability | Environment | 12.3 a | 13.0 ab | 14.0 b | 4.0 | 0.02 |

| Crowding | 6.0 | 6.4 | 7.3 | 1.7 | 0.18 | |

| Diversity | 8.9 a | 10.0 ab | 10.7 b | 7.6 | 0.00 | |

| Economy | 10.7 | 11.2 | 11.3 | 2.1 | 0.13 | |

| Model statistics: V = 0.06; F = 2.2; p = 0.02 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Andereck, K.L.; Vogt, C.A. Effect of Community Place Qualities on Place Value in a Destination. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4582. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104582

Andereck KL, Vogt CA. Effect of Community Place Qualities on Place Value in a Destination. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4582. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104582

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndereck, Kathleen L., and Christine A. Vogt. 2025. "Effect of Community Place Qualities on Place Value in a Destination" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4582. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104582

APA StyleAndereck, K. L., & Vogt, C. A. (2025). Effect of Community Place Qualities on Place Value in a Destination. Sustainability, 17(10), 4582. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104582