Abstract

This study explores how rural tourism destinations in the Eastern Carpathians of Romania have recovered in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. Using data from 2016–2019 and 2021–2023, five core indicators—tourist arrivals, overnight stays, accommodation capacity, occupancy rates, and active units—were analyzed at the local level. Based on these indicators, a cluster analysis was conducted for us to identify groups of communes with similar tourism performance profiles. After clustering, composite indicators were calculated to track how each group evolved over time. The findings show that recovery has not been uniform: while some destinations bounced back or even improved, others continue to face structural challenges. These results suggest that local infrastructure, destination type, and governance capacity all play a role in shaping recovery paths. The paper offers a spatial overview of rural tourism dynamics and highlights the value of using data-driven tools for understanding uneven development in post-crisis contexts.

1. Introduction

The Carpathian Mountains, which stretch over Central and Eastern Europe in a broad arc, are widely recognized for their cultural heritage and ecological richness. In Romania, they play a central role in rural tourism, where traditional village life, biodiversity, and scenic landscapes attract a growing number of visitors. The Carpathians influence not only Romania’s physical geography but also its rural development, including tourism, as Turnock [1] notes in one of his studies. Similarly, Iorio and Corsale [2] emphasize that mountainous regions offer valuable livelihood alternatives for rural communities through small-scale, community-based tourism initiatives.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, a global shift was already underway toward authentic, nature-based, and culturally immersive travel. Bramwell and Lane [3] underlined the role of partnerships in promoting sustainable tourism, while Lane and Kastenholz [4] observed that rural destinations were becoming increasingly popular among travelers seeking genuine experiences. However, the pandemic imposed unprecedented challenges on the global tourism sector.

While Bramwell and Lane [3] emphasized the need for partnerships in fostering sustainable tourism, Lane and Kastenholz [4] noted that rural destinations were growing in popularity among travelers looking for meaningful experiences. However, the pandemic posed unprecedented challenges to the global tourism sector.

Gössling et al. [5] characterized the crisis as a systemic shock that had a significant impact on rural and remote areas due to limited mobility and increased economic uncertainty. These difficulties were made worse in Romania by the country’s underdeveloped infrastructure and heavy reliance on domestic travel. According to Haller et al. [6], the sector’s resilience was hampered by these structural constraints. However, since domestic tourism temporarily switched toward low-density, nature-based sites, Gordan et al. [7] note that rural mountain destinations demonstrated relatively higher resilience during lockdowns.

Traveler choices around the world also influenced post-pandemic recovery trajectories. The World Tourism Organization [8] reported rising demand for outdoor, rural, and nature-oriented destinations. This trend was confirmed by Morar et al. [9], who found that health and safety concerns drove tourists to favor domestic and sparsely populated areas. But not every rural area benefited equally from these changes. Many previously ignored Romanian rural areas suffered considerable tourism losses as a result of reduced accessibility and continuous travel restrictions [10].

The pandemic’s recovery has revealed that rural mountain regions continue to experience persistent inequities. Resilient tourism is influenced by governance, infrastructure, and community participation [11]. Briedenhann and Wickens [12] highlighted the value of local creativity and networking in their earlier study in order to improve rural tourism. The development of sustainable tourism in the Carpathian region has been hampered by spatial and infrastructure disparities, as noted by Turnock [1] and Iorio and Corsale [2].

Despite its tourism potential, the Eastern Carpathians have received limited attention in post-COVID-19 research. Three main factors make this location the subject of our study. It is emblematic of the characteristics of rural tourism in general since it provides a range of tourism experiences, including ecotourism, wellness tourism, and cultural heritage tourism [2]. Second, it allows for a comparative analysis of resilience by incorporating both affluent and impoverished regions. Third, compared to the well-studied Southern Carpathians, the Eastern Carpathians are still relatively unknown; therefore, there is still opportunity for new contributions. Such studies as those by Mureșan et al. [13,14], who examined locals’ opinions on tourism in the same area, and Mitrică et al. [13,14], who examined cultural tourism difficulties in the Buzău Carpathians and Subcarpathians, are starting to bridge this divide [13,14].

This current study assesses post-COVID-19 recovery in the Eastern Carpathians by using data-driven analysis of five important tourist variables over two time periods, 2016–2019 (pre-pandemic) and 2021–2023 (post-pandemic), to contribute to this expanding field. We use K-means clustering to classify locales into different recovery profiles and create a composite recovery index using weighted Z-scores. Combining cluster analysis, composite indexing, and statistical comparison, this study offers a diagnostic evaluation of recovery, as well as tactical recommendations for the growth of rural tourism in mountainous areas.

This paper aims to make us better understand how rural mountain tourism in the Eastern Carpathians has recovered following the COVID-19 crisis. It examines changes over time in key tourism indicators—such as arrivals, overnight stays, and accommodation capacity—and compares how different destinations have fared in terms of recovery. The main goals are to group the destinations based on tourism performance, to explore spatial variations, and to identify which areas have shown more or less resilience in the years after the pandemic. What makes this study distinct is its strong focus on the local level and its use of a combined methodological approach—clustering and index-based analysis—to offer a more nuanced picture of how recovery has played out across this diverse mountain region.

2. Literature Review

With rural and mountainous areas displaying unique problems and recovery paths, the COVID-19 epidemic significantly affected the tourism industry globally. This review of the literature shows new findings on the effects of the pandemic on rural tourism, post-crisis recovery plans, resilience assessment with composite metrics, and recovery patterns using cluster analysis.

The initial COVID-19 epidemic caused unprecedented disruptions to the travel and tourism sector. Duro et al. [15] developed a vulnerability score for Spain’s provinces, showing that regions that relied on tourism, particularly rural areas, faced severe challenges due to reduced mobility and uncertain economy. The active engagement of various age and social groups in tourism-related activities was further highlighted by Mazilu and Niță’s [16] investigation of the Romanian tourism industry’s response to economic shocks, including the COVID-19 epidemic.

From a geographical perspective, Cehan et al. [17] analyzed tourism demand patterns in Romania, identifying interregional disparities and diverse recovery trajectories. Their findings reveal that, despite the appeal of nature-based tourism, rural areas suffered setbacks related to infrastructure weaknesses and health-related travel constraints. Mitrică et al. [14] in their study with regard to Buzău Carpathians and Subcarpathians, shows that travel restrictions and social-distancing policies significantly impacted cultural tourism in many rural mountain areas. The result was significant financial losses and the temporary closure of numerous businesses.

Expanding this view, recent studies such as the one that Damian et al. [18] took part in explored the broader impact of the pandemic on rural tourism across Europe, including Romania. They highlighted several consequences, such as revenue declines, service disruptions, and employment losses in tourism, and called for increased innovation and capacity-building at the local level [18]. Also, when Roznoviețchi et al. [19] investigated locals’ impressions of the cultural tourism recovery, they found a cautious optimism that was reliant on better infrastructure and public health protections.

Chivu and Stanciu [20] analyzed Romania’s agritourism sector, identifying structural characteristics and regional disparities, and emphasized the importance of tailored development strategies to unlock its growth potential. According to Gordan et al. [7], Romanian tourism’s operational capacity surpassed pre-pandemic levels following the initial crisis, demonstrating the industry’s innate resilience and adaptability.

Resilience is commonly characterized in tourism studies as a system’s capacity to withstand shocks and adapt to change [21]. In rural tourism, this includes the ability of destinations, businesses, and communities to adapt to crises while preserving their core functions [11]. Recent studies emphasize adaptive capacity, innovation, and governance as key components of tourism resilience [22].

As the tourism sector looks toward recovery, various strategies have been proposed to revitalize rural destinations. According to the World Tourism Organization [8], which suggests that there is a window of opportunity for these places to play a major part in post-pandemic recovery efforts, rural and nature-based destinations are becoming more popular worldwide. Galluzzo [23], who studied the development of agritourism in Romania, confirms that subsidies from the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) have been essential in assisting small farms and advancing tourism centered on mountains.

In 2021, Mărcuță et al. examined the wider socioeconomic impacts of the pandemic on Romanian tourism, emphasizing the value of community resilience and providing financial adaptation strategies [24], and Mitrică et al., in the same year, developed a comprehensive methodology to evaluate the growth of sustainable tourism in Romanian counties using geographical indicators. They called for distinct policy responses after their analysis showed glaring differences between rural and urban locations [25].

Crețu et al. [26] conducted fieldwork among rural mountain tourism operators in Romania, revealing that many businesses maintained or even improved their performance during the pandemic—an indication of the sector’s resilience under challenging circumstances. According to Mazilu et al., who highlighted domestic travel as a crucial component of resilience in the same year, increasing domestic travel should continue to be a long-term goal [16].

Bacter et al. [27], in 2024, explored how economic and legislative issues affected the agritourism industry in Romania. After they identified the regional differences through a SWOT analysis, they proposed some plans for competitive and sustainable growth [27]. Additionally, a European study on the pandemic’s impact on rural tourism created by Damian et al. [18] promoted institutional innovation and community-based recovery strategies.

The crisis also accelerated the adoption of digital technologies in tourism, especially in rural and nature-focused destinations. According to Sigala [28], the pandemic catalyzed the integration of digital tools—such as contactless services, virtual promotion, and online booking systems—as a means of maintaining operations and customer engagement. At the same time, Gretzel et al. [29] argued that digital transformation has become essential for tourism resilience, enabling businesses to respond to shifting consumer behaviors and improve their competitiveness. However, progress in digital adoption has been uneven. Many rural destinations face infrastructural, financial, and human-capital barriers that hinder the effective use of advanced digital solutions, which may exacerbate existing competitiveness gaps [8].

Even though Romania boasts diverse and attractive mountain regions, academic re-search has largely focused on popular areas such as Brașov, Sibiu, and the Prahova Val-ley. By contrast, the Eastern Carpathians have received comparatively little scholarly attention, especially regarding post-pandemic recovery dynamics. Addressing this gap, the current study applies a composite indicator framework and cluster analysis to assess the performance of rural tourism in the Eastern Carpathians after COVID-19, offering new insights into a region with notable but underutilized tourism potential [30].

The literature review highlights the complex connection that appears between adaptive capability, resilience, and vulnerability in the recovery of rural mountain tourism. In order to evaluate local post-pandemic tourism success, very few research studies have employed data-driven, integrated techniques, particularly in the Eastern Carpathians, an area that has received little attention. So, for us to fill this gap, recovery trends across mountain rural destinations are compared and identified using cluster analysis and composite factors.

Much of the existing research on mountain tourism and post-COVID-19 recovery has focused either on national-level trends or on individual case studies. While these studies offer important insights, they often miss the local differences that can exist even within the same region. There is still a lack of comparative research at the local level, especially when it comes to rural and mountain destinations. This study helps fill that gap by using official data at the commune level and applying quantitative methods to capture differences in how areas have recovered. In doing so, it provides a fresh, complementary perspective that brings spatial disparities to the forefront—differences that are often overlooked in broader, national-level analyses.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources and Analyzed Period

The official national data used in this study were sourced from official national databases, focusing exclusively on rural mountain localities located in the Eastern Carpathians [31]. The analysis covers two distinct timeframes: the pre-pandemic period (2016–2019), which serves as the baseline, and the post-pandemic period (2021–2023), reflecting the recovery phase. The year 2020 was deliberately excluded due to the extreme nature of mobility restrictions and distortions in tourism flows, which could compromise the accuracy and comparability of the analysis.

3.2. Selected Indicators

To evaluate the recovery of rural tourism in the mountainous areas of the Eastern Carpathians, five core indicators were selected: number of tourist arrivals, accommodation capacity (measured by the number of beds), number of operational accommodation units, number of overnight stays, and occupancy rate.

For each indicator, annual averages were generated for both observation periods. Additionally, the percentage change for two periods was calculated. To allow the creation of a composite recovery index, weighted Z-scores were used to derive the standardized values of these indicators. This method makes it possible to compare the recovery performance of tourism in various locations [32,33,34].

3.3. Analytical Methodology

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 27. To ensure data quality, descriptive statistics were used to identify outliers and inconsistencies. Although Cronbach’s alpha test is often employed to evaluate internal consistency when aggregating multiple indicators, the primary focus of this study was on tracking changes over time. Therefore, reliability was assessed based on the consistency of Z-scores derived from the data and the stability of the clustering solutions across the selected time periods. The analytical process was structured as follows:

- Descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum, were calculated for each of the five tourism indicators for both the pre- and post-COVID-19 periods. Using paired-sample t-tests, which were implemented in SPSS via analyze > compare means > paired-samples t-test, the average values of those indicators were compared. This was performed to find broad trends in the tourist recovery. Via this statistical technique, the identification of notable performance differences between the pre- and post-pandemic periods was made possible. To determine whether the mean differences between the two periods were statistically significant, a paired-sample t-test was performed for each indicator. A p-value of less than 0.05 suggests a significant change in tourism performance, and the null hypothesis states that the mean difference is equal to zero.

- Cluster analysis, from a methodological standpoint, is frequently employed to promote more focused policy interventions by grouping locations with comparable development or recovery profiles [35]. The cluster analysis was used in this study to evaluate the variation in recovery paths across rural mountain communities. First, for each of the five indicators in both periods (2016–2019 and 2021–2023), the arithmetic mean was determined. Next, each indicator’s percentage change (PC) was calculated using the formula below:

In this specific case, Meanpost and Meanpre, by representing the arithmetic means of each indicator during the pre-pandemic and post-pandemic eras, show the relative change over time. Regardless of the direction of the change (i.e., even when the values go from negative to positive), the use of absolute values guarantees that the outcome captures the degree of change. Our approach is also aligned with the suggestions made in 2005 by Nardo et al. [36] and in 2008 by OECD [32]. We used Ward’s approach, which minimizes within-group variability and guarantees that the final clusters are as homogeneous as feasible, to apply hierarchical clustering in order to establish the ideal number of clusters. The best option had four different groups, according to the agglomeration schedule and the dendrogram. We used a K-means clustering technique in SPSS to divide those 66 rural mountain communes into four clusters, each representing a unique post-pandemic recovery pattern, based on the five percentage-change indicators. Two additional composite indices were developed, the Pre-Pandemic Tourism Performance Index (PTPI) and the Post-Pandemic Tourism Performance Index (PoTPI), in order to evaluate the comparative performance of the identified clusters. Composite indicators are increasingly employed in tourism research to condense multidimensional performance data into a single interpretable metric, thereby facilitating meaningful cross-regional comparisons [37]. All indexes were calculated as the arithmetic mean of Z-scores for the five tourism indicators, computed separately for each reference period. In constructing the composite index, all five indicators (tourist arrivals, accommodation capacity, number of operating units, overnight stays, and occupancy rates) were standardized using Z-scores and assigned equal weights. Because there was no strong theoretical or empirical reason to prioritize one aspect of tourism performance over another, we chose this method to avoid introducing subjectivity through weighting. By treating all indicators as equally important, the resulting indices offer a straightforward yet reliable way to compare the performance of each cluster before and after the pandemic. Then, descriptive statistics were employed to compare cluster profiles in time. By analyzing differences between the PTPI and PoTPI values, the study identified which clusters demonstrated stronger resilience and recovery, and which were more adversely affected. The difference between the two indices served as a central metric for tracking the relative trajectory of recovery across clusters [38].

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. The Evolution of the Tourism Sector: Pre-COVID-19 vs. Post-COVID-19

An initial understanding of the shifts in key tourism performance indicators is provided by descriptive statistics. The trend observed across all five mentioned metrics—tourist arrivals, accommodation capacity, number of operational units, overnight stays, and occupancy rate—suggests a positive path of recovery in the rural tourism sector of mountainous regions following the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for five core indicators used to assess the evolution of rural tourism in mountain areas before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The data reveal a general upward trend across all indicators, indicating a recovery trajectory; however, the wide variability between localities underscores a highly uneven process.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for pre-COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 indicators.

Tourist arrivals increased from a pre-pandemic mean of 1578.8 (SD = 2173.5) to 2133.0 (SD = 3157.6) in the post-pandemic period, representing a 30.8% average increase. The minimum value dropped slightly (from 49.0 to 39.0), while the maximum rose sharply (from 13,285.3 to 20,757.7), suggesting that although some destinations performed exceptionally well, others continued to experience very low visitation. This discrepancy is validated by a range of percentage change (−92.5% to 216.8%). Although tourism is recovering, the scope and rate of this recovery differ, as per the estimates. Elements like marketing visibility, accessibility, or the capacity to adjust to changing health and safety regulations, contributed to these disparities.

The number of operational accommodation units also saw a substantial increase, from an average of 3.5 to 5.8 units per locality (41.2% change). The SD increased only slightly (from 5.6 to 6.6), while the range shifted from 0.5–35.3 to 1.0–33.7. This suggests that while more localities improved their operational capacity, the expansion remained moderate and somewhat conservative. A range of changes from −50.0% to +300.0% further highlights structural imbalance: some areas have expanded significantly, while others have either stagnated or experienced a decline in active tourism facilities. This variation may reflect differing levels of public or private investment, confidence in market demand, or even management capacity at the local level.

In terms of accommodation capacity (number of available beds), the average increased from 18,589.0 to 22,571.5, amounting to a 21.4% rise, with standard-deviation values also increasing (from 23,191.7 to 28,031.8). The wide gap between minimum and maximum values (pre: 2000.0–161,871.5; post: 1365.3–179,840.0) demonstrates that growth has been unevenly distributed. The average percentage change of 21.4%, with a range from −66.1% to 162.3%, indicates that some destinations were able to expand their hosting capacity significantly, while others may have suffered losses due to closures or underinvestment. Despite persistent differences in regional distribution and capacity to accommodate rising demand, all of these findings point to a partial structural recovery in supply.

The number of overnight stays, often seen as a proxy for visitor retention and economic impact, rose from 3270.5 to 4327.2 (+29.6%). The increase, along with the rise in maximum values (from 29,588.0 to 43,118.3), suggests a potential change in tourist behavior, perhaps a propensity for longer visits, as well as a volume recovery. The percentage changes ranged from −87.1% to +200.3%, and the variability is still high (SD = 6600.4 post-COVID-19), further indicating that some places have rebounded robustly while others are still lagging. This could be affected by differences in destination perception, additional services, accommodation quality, or attractiveness.

Finally, the occupancy rate remained remarkably stable, increasing only slightly from 16.4% to 17.5% (SD unchanged at 11.4), representing a modest 6.4% increase. This relative stability, despite notable increases in both capacity and visitation, suggests that supply and demand have evolved in parallel. The range of occupancy changes (from −78.9% to +136.4%) says that even if it also identifies outliers in both directions, the real use and tourism infrastructure are largely balanced. This could also indicate the flexibility of the service providers, possibly including flexible pricing; improved responsiveness to shifting demand; or adjusted operational procedures.

The descriptive data point out to a broad recovery in the areas from Eastern Carpathian rural mountain tourism, with some important exceptions. Even though the aggregate numbers are increasing, the wide ranges and standard deviations between locations suggest that the recovery is impacted by a multitude of infrastructure, governance, and economic issues. All these results support the use of cluster analysis in the following section to determine regional patterns of divergence and resilience.

Results of paired-samples t-tests comparing tourism performance metrics before and after the pandemic (2016–2019 and 2021–2023) are shown in Table 2. The results show statistically significant gains in four of the five important indicators, pointing to a robust rebound in mountainous rural tourism.

Table 2.

Paired samples test.

The mean difference in tourist arrivals is −554.2, with a standard error of 155.8. This indicates that, on average, each locality recorded approximately 554 more arrivals in the post-COVID-19 period than before the pandemic. The result is statistically significant (t = −3.6, df = 65, and p = 0.001), highlighting a substantial rebound in visitation levels.

For accommodation structures, the average increase is approximately 1.3 units per locality (t = −3.8, p < 0.001), signaling growth in tourism infrastructure and possibly greater investor confidence in rural tourism development.

The accommodation capacity, measured by the number of available beds, also increased significantly. The average difference of −3982.4 units (t = −3.2, p = 0.002) indicates that rural locations have increased their capacity to receive tourists, supporting the tourism industry’s structural recovery following the pandemic. The number of overnight stays shows a similar trend, increasing by an average of 1056.6 nights per locality (t = −3.3, p = 0.002). This means that the tourists not only returned but also began to stay longer, which may have a greater economic impact per visitor and more benefits for the neighborhood. However, there was no appreciable variation in the occupancy rate between the two time periods. Although both supply and demand increased proportionately, the mean difference of −0.09 was not statistically significant (t = −0.09, p = 0.928), indicating that the utilization rate remained relatively stable.

This being said, the results point to a statistically supported recovery in rural mountain tourism, particularly in terms of arrivals, overnight stays, and infrastructure expansion. The lack of change in occupancy rates reflects a balanced relationship between increased capacity and rising demand, implying an efficient adaptation to post-pandemic conditions. These patterns confirm that rural destinations in the Eastern Carpathians have shown resilience and a capacity to rebuild following the disruptions caused by COVID-19.

4.2. Recovery Dynamics in Rural Tourism: An Empirical Cluster Analysis

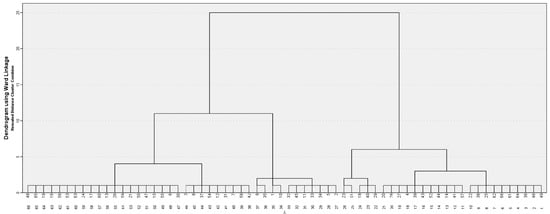

Using Ward’s approach and Squared Euclidean Distance as the measure of dissimilarity, the hierarchical cluster analysis was conducted to find unique recovery patterns among rural mountain destinations. The agglomeration schedule and subsequent dendrogram were closely inspected in order to find natural groups in the data. We paid particular attention to notable jumps in fusion coefficients, indicating optimal cluster separation. Among the 66 rural areas that were analyzed, this research revealed four distinct clusters that demonstrate the wide variation in post-pandemic tourism recovery (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Dendrogram of cluster analysis of Eastern Carpathian communes based on tourism performance indicators—authors’ own calculations using SPSS.

These clusters capture both the scale and nature of divergence in recovery performance and serve as a basis for further interpretation of resilience dynamics at the destination level.

As summarized in Table 3, the distribution of cases across clusters reflects a well-balanced segmentation of the 66 rural mountain communes. Specifically, Cluster 1 includes 9 cases (13.6%), Cluster 2 has 7 cases (10.6%), Cluster 3 comprises 22 cases (33.3%), and Cluster 4 includes 28 cases (42.4%). This relatively even distribution supports the stability and internal consistency of the clustering solution.

Table 3.

Number of cases per cluster and the distances between cluster centers.

Moreover, the distinctiveness of each group is confirmed by the distances between cluster centers. For instance, the highest dissimilarity is observed between Clusters 2 and 3 (3.10), suggesting markedly different recovery profiles. These clearly defined groupings reinforce the use of cluster analysis as an effective tool for differentiating local tourism performance and capturing the heterogeneity of post-pandemic recovery dynamics.

The pairwise distances between the final cluster centers, calculated using Squared Euclidean Distance, offer a reliable quantitative indicator of how different each cluster is in terms of post-pandemic tourism recovery performance. As shown in Table 3, the largest inter-cluster distance between Clusters 1 and 2 (2.888) indicates significant differences in the underlying characteristics of the localities within these two groups, while the smallest distance—between Clusters 3 and 4 (1.47)—indicates that these clusters have more similar profiles.

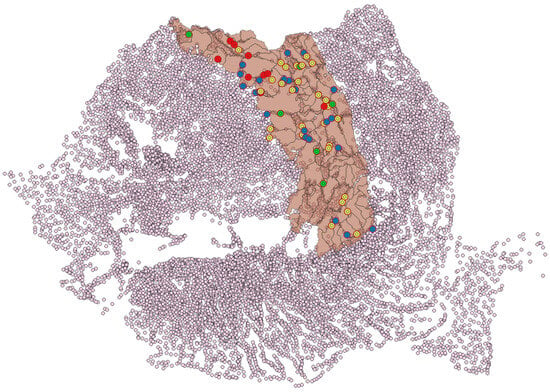

In Figure 2, we can see the spatial distribution of the clusters, thus further supporting these considerable statistical discrepancies. A majority of the red-highlighted communes in Cluster 1 are found in the Eastern Carpathians’ northern region. Cluster 2’s (green) geographic distribution is more scattered and remote, with locales dispersed throughout the area rather than concentrated in a single location. Clusters 3 and 4 (yellow and blue, respectively) exhibit a broader spatial distribution, with portions spanning both the central and southern Carpathian arcs.

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of clusters—authors’ own calculations using IBM SPSS Statistics 27 and QGIS Desktop 3.42.1.

This spatial distribution demonstrates a geographically uneven recovery of rural tourism. Both regionally concentrated clusters and spatially fragmented clusters were identified, highlighting the interaction between territorial context, accessibility, local governance capacity, and resource endowments. All of this underlines the importance of developing strategies in the field of tourism that take into account local conditions and are adapted to the specific characteristics and needs of the rising areas of the Eastern Carpathians.

For the uniqueness of the recovery patterns found by clustering to be confirmed, a one-way ANOVA test was performed for each of the five standardized tourism performance metrics. All variables analyzed showed statistically significant differences (p < 0.001) among clusters, according to the results shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

ANOVA test.

With the highest F-value (F = 95.0; df = 3.62), the occupancy rate stands out, indicating a pronounced disparity in how efficiently localities utilize their available accommodation infrastructure. This suggests that while some clusters are successfully matching supply with demand, others are struggling to attract sufficient overnight stays relative to their capacity. Similarly, the percentage change in operational accommodation capacity shows the significant inter-cluster variation (F = 25.1). This reflects regional differences in infrastructure development and investment levels. While some of the destinations have significantly increased their capacity, others have stayed the same or have risen more slowly.

Furthermore, there are statistically significant differences in the percentage change in the number of lodging units (F = 20.8) and visitor arrivals (F = 21.8). These findings suggest that the clusters are not equally distributed in terms of supply-side responses and demand-side dynamics. As evidenced by the percentage change in overnight stays, which also exhibits substantial variation (F = 17.8), visitor behavior and destination performance differ significantly among groups.

Taken together, the ANOVA results offer robust statistical confirmation of the segmentation validity. The high F-values for all measures imply that the clusters are not only different in terms of composition but different also in terms of performance, with some groups that are adjusting to post-pandemic settings more successfully than others. These results offer a solid empirical basis for additional qualitative analysis of cluster attributes and the creation of customized policy suggestions for tourism.

It was revealed through the comparative analysis of post-COVID-19 tourism indicators across clusters that significant disparities exist in performance among rural mountain communes. These cluster profiles show different degrees of structural preparedness for recovery and adaptive capacity, in addition to statistical differences. Access to tourism markets, governance efficacy, and infrastructure quality are examples of potential explanatory factors. Looking at Cluster 4, we can observe that it maintained the highest values across all key tourism indicators, both before and after the pandemic. This consistency suggests to us a solid and resilient tourism structure. Maybe this performance is supported by well-developed infrastructure, effective local leadership, and a more diverse range of tourism services. It is also possible that these localities benefited from specific investments or improved online visibility during the recovery period, which helped them remain attractive and competitive. Cluster 3, on the other hand, shows a noticeable decline compared to pre-pandemic levels, especially in overnight stays and occupancy rates. This trend may reflect deeper structural issues, such as poor infrastructure, geographic isolation, or maybe a lack of sustained institutional support. Some destinations from this group might still rely on outdated tourism models and may not have the flexibility or the tools to adapt to changing market expectations.

Looking at Cluster 1, we see that its performance remains relatively low but stable over time. These places may have a decent infrastructure base, but they might not be using it to its full potential. Challenges such as weak local promotion, limited strategic planning, or inconsistent policy support could explain why these areas are not progressing, despite having the necessary resources.

As shown in Table 5, Cluster 4 stands out as the top-performing group, with the highest average values for most indicators: 3144 tourist arrivals, an operational capacity of 29,479.6 beds, an average of 6363.1 overnight stays, and an occupancy rate of 20.8%. These results suggest that localities in this cluster were able to recover quickly and sustain high levels of tourism activity following the pandemic.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics for touristic indicators and composite indices by cluster.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, Cluster 3 exhibits a markedly lower performance. The average number of arrivals is only 703.2, operational capacity is 12,373.4 beds, and overnight-stay average is 1515.7, with the lowest occupancy rate across all clusters at 11.8%. These numbers show that remote mountain locations in Cluster 3 are struggling to attract and retain tourists, as they are the most vulnerable group in the post-COVID-19 age. Given that several sites from both clusters are located in adjacent Eastern Carpathian regions, the close proximity of Clusters 3 and 4 is very significant. Despite having the same spatial location, their recovery paths are quite different. This disparity shows the significance of local-level elements, such as government assistance, or infrastructure quality, service delivery, and market accessibility, to determine a destination’s capacity to recover from a disaster. The findings further support the need for tailored interventions rather than relying on conventional recovery methods to address the particular issues of underperforming areas. Clusters 1 and 2 present intermediate performance profiles, each with distinct structural characteristics. Cluster 1 reports moderate levels of arrivals (2360.7) and a relatively high operational capacity (28,551.7), suggesting a solid infrastructure base. In contrast, Cluster 2 has a similar number of arrivals (2289.6), but a much lower capacity (19,301.6 beds), and yet it records the highest occupancy rate (23.5%) of all clusters. This difference illustrates contrasting approaches to capacity utilization: Cluster 2 operates efficiently on a smaller scale, while Cluster 1 has greater infrastructure that may still be underutilized.

To sum up performance across multiple dimensions, two composite indices were calculated: the Pre-Pandemic Tourism Performance Index (PTPI) and the Post-Pandemic Tourism Performance Index (PoTPI). These indices, based on standardized Z-scores, provide a unified measure of overall tourism performance, facilitating comparison between clusters and time periods. The results showed varied recovery paths:

- Cluster 4 keeps the highest post-pandemic composite index (0.273) and reflects a consistently strong performance. The cluster was also scored positively before the pandemic (0.229), and the modest increase (mean change = 0.043) suggests a continuation of pre-existing success rather than a dramatic recovery.

- Cluster 1 follows with a PoTPI of 0.107, representing a shift from a slightly negative pre-COVID-19 position (PTPI = −0.090) to a positive post-COVID-19 status. The mean change of 0.197 indicates a moderate but meaningful recovery in performance.

- Cluster 2 shows the most pronounced improvement, increasing from −0.223 to 0.055—a mean change of 0.279. Even though Cluster 2 still ranks lower than Clusters 1 and 4 in absolute terms, the sharp increase reflects strong recovery momentum.

- Cluster 3, however, experienced a decline in composite performance, with the index dropping from −0.185 pre-pandemic to −0.408 post-pandemic (mean change = −0.224). This regression highlights serious challenges in post-crisis adaptation and the risk of long-term marginalization for destinations in this group.

The descriptive and composite indicator analysis confirms the heterogeneity of tourism recovery among rural mountain destinations in the Eastern Carpathians. While some clusters (notably Cluster 4) demonstrate resilience and continuity, others (particularly Cluster 3) reflect structural vulnerabilities. These findings reinforce the importance of place-based, evidence-driven strategies that align policy support with the specific recovery dynamics and needs of each cluster.

4.3. Discussions

The findings of this study reflect significant differences in how rural destinations in the Eastern Carpathians have recovered from the COVID-19 crisis. Beyond their statistical dimension, these variations reveal broader structural and contextual realities that influence tourism resilience. Similar observations have been made in earlier studies that underline the uneven impact of the pandemic on rural tourism [10,15].

The consistently strong performance of certain localities, such as those in Cluster 4, appears to confirm what previous research has suggested: destinations with better-developed infrastructure, more diverse tourism services, and stronger local leadership tend to be more resilient in the face of disruption [5,26].

In contrast, other groups, such as those included in Cluster 3, remain more vulnerable. Lower occupancy and overnight-stay values are likely tied to persistent challenges like poor accessibility, lack of coordinated local support, and reduced adaptability. These characteristics match the profiles identified in other studies focused on remote rural areas with limited institutional backing [14,19].

Interestingly, the improvement observed in Cluster 2 aligns with international findings, which show that destinations offering outdoor, less crowded, and nature-based experiences recovered faster [9]. This could also be a sign of how quickly some communities were able to reorganize and adapt their tourism offer to meet post-pandemic demand.

By comparing our results with other findings in the literature, we confirm that recovery in rural tourism is not uniform and depends on a combination of local factors—economic, infrastructural, and administrative. These insights support the idea that tailored, context-sensitive strategies are essential when addressing rural recovery in regions as diverse as the Eastern Carpathians.

5. Conclusions

This study focused on rural mountain sites in the Eastern Carpathians and offered a comprehensive assessment based on statistical analysis of post-COVID-19 recovery patterns in Romania’s rural tourism industry. The five most significant performance characteristics were compared between the pre-pandemic (2016–2019) and post-pandemic (2021–2023) periods using cluster analysis and paired-sample t-tests. This made it easier for us to pinpoint both the general and particular recovery characteristics. These metrics include visitor arrivals, lodging establishments, occupancy rates, overnight stays, and functional accommodation capacity.

The paired-samples t-tests reveal statistically significant improvements in tourist arrivals, infrastructure, operating capacity, and nights stayed, all indicative of a robust recovery in tourism demand following the COVID-19 disruption. The occupancy rate, however, was largely constant, indicating that rising traveler demand was counterbalanced by matching increases in lodging supply. This well-rounded evolution shows the industry’s adaptive reaction, but it also draws attention to the difficulties in guaranteeing effective resource use [38].

Hierarchical and K-means clustering analyses have uncovered heterogeneous recovery profiles among the 66 rural mountain destinations. Notably, while Clusters 1 and 2 exhibit positive developments (with significant increases in arrivals and extended stays), Cluster 3 demonstrates declining performance. Spatial studies support the idea that physically adjacent locations, such as Cluster 3 or 4, might have different recovery outcomes, and this shows how locality-specific factors, like poor infrastructure or lax local regulations, can make recovery more challenging, even within the same location. These conclusions are also supported by composite index research, which demonstrates that even though Cluster 4 was performing well prior to the outbreak, it has only marginally improved. Clusters 1 and 2 demonstrate significant improvements, but Cluster 3’s lower overall score suggests ongoing challenges in drawing and keeping tourists [39]. The heterogeneity of recovery paths calls for regionally targeted policies and interventions. Tailored support for lagging clusters such as infrastructure enhancement, building capacity, and digitalization can accelerate recovery and can also promote more balanced, sustainable tourism development in the Eastern Carpathians side [40].

Our analysis shows that the recovery of rural tourism in the Eastern Carpathians has been far from uniform. Some destinations bounced back relatively quickly, while others are clearly struggling. In many cases, these differences reflect how well these were prepared in terms of infrastructure, visibility, and local organization. For areas that are still struggling, even modest support—better signage, online promotion, or coordination between actors—could make a meaningful difference.

Although the study was based on statistical indicators, the findings also raise questions about the importance of less visible factors. How destinations communicate, how communities are involved, and how local leaders respond to change likely play a bigger role than we can measure directly. Other studies have already suggested that good coordination and digital presence can tip the balance in a destination’s favor [41,42].

This is particularly relevant in specific areas of the Eastern Carpathians, such as Vatra Dornei or Borsec, which have long attracted visitors due to their spa traditions, fresh air, and scenic surroundings. These places often combine natural assets with cultural heritage, and their recovery appears to benefit from that mix. Other localities, like Fundata or the Moinești area, are appealing for their quiet rural atmosphere, traditional homes, and access to hiking trails. These characteristics have gained value especially in the post-pandemic period, when tourists increasingly prefer open-air, low-density destinations [43,44].

All of these findings underline the fact that rural tourism is not just about an economic return, but also about the vitality of small communities, environmental stewardship, and cultural continuity. The recovery time offers a chance not only to rebuild but also to rethink local development strategies in ways that prioritize long-term resilience and balance.

To sum up, the patterns we have identified in this paper offer a practical view of how things are evolving on the ground. Hopefully, this kind of analysis can help guide more flexible, localized policies that respond to what each place actually needs. Also, these findings may be useful for other rural or mountain areas beyond the Eastern Carpathians, where recovery has been similarly uneven and dependent on local conditions. Of course, the analysis has its limits. It relies on available statistical data and does not include qualitative aspects such as local governance, resident involvement, or visitor perceptions. A follow-up study could explore these dimensions to obtain a fuller picture of what helps certain places recover more quickly than others.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.D. and E.T.; data curation, A.-C.L.; formal analysis, E.T.; funding acquisition, C.D.; investigation, A.-C.L.; methodology, E.T.; project administration, C.D.; software, A.M.I.; supervision, C.D.; validation, C.D., E.T. and A.M.I.; visualization, E.T.; writing—original draft, E.T. and A.-C.L.; writing—review and editing, A.-C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The publication of this article was possible thanks to project no. 844/30 June 2023, Evaluation of authenticity in rural guesthouses in Romania, financed by USAMV Bucharest.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Turnock, D. The Economy of East Central Europe, 1815–1989. Stages of Transformation in a Peripheral Region; Routledge–Taylor and Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 0-203-59843-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorio, M.; Corsale, A. Rural tourism and livelihood strategies in Romania. J. Rural Stud. 2010, 26, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Tourism Collaboration and Partnerships. Politics, Practice and Sustainability; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2000; ISBN 9780585354224. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, B.; Kastenholz, E. Rural tourism: The evolution of practice and research approaches—Towards a new generation concept? J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1133–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, A.-P.; Hârșan Tacu, G.D.; Ungureanu, D. Romanian Rural Tourism in International Context. Present and Prospects; Romanian Academy, Iași Branch, “Gheorghe Zane” Institute for Economic and Social Research: Iași, Romania, 2021; ISBN 978-606-685-836-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gordan, M.-I.; Adamov, T.C.; Merce, I.I.; Milin, I.A.; Pascariu, A.R.; Iancu, T. Is Romanian Rural Tourism Resilient to External Shocks? Case Study: COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdowns and Their Consequences. Lucr. Ştiinţifice Manag. Agric. 2024, 26, 286–290. [Google Scholar]

- UN Tourism. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/rural-tourism (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Morar, C.; Tiba, A.; Basarin, B.; Vujičić, M.; Valjarević, A.; Niemets, L.; Gessert, A.; Jovanovic, T.; Drugas, M.; Grama, V.; et al. Predictors of Changes in Travel Behavior during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Tourists’ Personalities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, R. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourism in Romania in 2020 with Special Regard on Marginal Rural Areas. In COVID-19 and Marginalisation of People and Places. Perspectives on Geographical Marginality; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-3-031-11139-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Prayag, G.; Amore, A. Tourism and Resilience: Individual, Organisational and Destination Perspectives; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1845416294. [Google Scholar]

- Briedenhann, J.; Wickens, E. Tourism routes as a tool for the economic development of rural areas—Vibrant hope or impossible dream? Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mureșan, I.C.; Oroian, C.F.; Harun, R.; Arion, F.H.; Poruțiu, A.; Chiciudean, G.O.; Todea, A.; Lile, R. Local Residents’ Attitude toward Sustainable Rural Tourism Development. Sustainability 2016, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrică, B.; Grigorescu, I.; Mocanu, I.; Șerban, P.-R.; Damian, N.; Dumitrașcu, M.; Dumitrică, C. COVID-19 Pandemic and Local Cultural Tourism in the Buzău Carpathians and Subcarpathians (Romania). Healthcare 2022, 10, 2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duro, J.A.; Perez-Laborda, A.; Turrion-Prats, J.; Fernández-Fernández, M. COVID-19 and tourism vulnerability. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 38, 100819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazilu, M.; Niță, A.; Draguleasa, I. Resilience of Romanian Tourism to Economic Crises and COVID-19 Pandemic. WSEAS Trans. Bus. Econ. 2023, 20, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cehan, A.; Iațu, C. A geographical perspective on the impact of COVID-19 on tourism demand in Romania. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2024, 52, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damian, C.M.; Smedescu, D.I.; Panait, R.; Buzatu, C.S.; Vasile, A.; Tudor, V.C. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on rural tourism in Europe. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2024, 24, 407–412. [Google Scholar]

- Roznoviețchi, I.; Damian, N.; Mitrică, B.; Grigorescu, I.; Șerban, P.R.; Dumitrașcu, M.; Dumitrică, C. Cultural Tourism in Predominantly Rural Communities. Residents’ Perception in Buzău Carpathians and Subcarpathians (Romania). Eur. Countrys. 2024, 16, 437–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivu, M.; Stanciu, S. Agritourism Market in Romania: Potential, Concentration, and Development Perspectives. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2024, 24, 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, D.; Hall, C.M.; Stoeckl, N. The resilience of formal and informal tourism enterprises to disasters: Reef tourism in Phuket, Thailand. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 20, 645–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amore, A.; Prayag, G.; Hall, C.M. Conceptualizing Destination Resilience from a Multilevel Perspective. Tour. Rev. Int. 2018, 22, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzo, N. A Technical Efficiency Analysis of Financial Subsidies Allocated by the CAP in Romanian Farms Using Stochastic Frontier Analysis. Eur. Countrys. 2020, 12, 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mărcuță, L.; Popescu, A.; Mărcuță, A.; Tindeche, C.; Smedescu, D. The Impact of the COVID-19 Crisis on Tourism and Its Recover Possibilities. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2021, 21, 495–500. [Google Scholar]

- Mitrică, B.; Șerban, P.-R.; Mocanu, I.; Damian, N.; Grigorescu, I.; Dumitrașcu, M.; Dumitrică, C. Developing an Indicator-Based Framework to Measure Sustainable Tourism in Romania. A Territorial Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crețu, R.C.; Gurban, G.; Alecu, I.I.; Ștefan, P. Did the Rural Mountain Tourism in Romania Pass the Resilience and Sustainability Test During the COVID-19 Pandemic? Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2023, 23, 203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Bacter, R.V.; Gherdan, A.E.M.; Dodu, M.A.; Ciolac, R.; Iancu, T.; Pîrvulescu, L.; Brata, A.M.; Ungureanu, A.; Bolohan, R.M.; Chebeleu, I.C. The Influence of Legislative and Economic Conditions on Romanian Agritourism: SWOT Study of Northwestern and Northeastern Regions and Sustainable Development Strategies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Fuchs, M.; Baggio, R.; Hoepken, W.; Law, R.; Neidhardt, J.; Zanker, M. e-Tourism beyond COVID-19: A call for transformative research. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2021, 22, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D. Dracula tourism in Romania: Cultural identity and the state. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 746–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Statistics. Baze de Date Statistice—TEMPO—Online Serii de Timp. Available online: http://statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online/#/pages/tables/insse-table (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- OECD. Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, S.; Ishizaka, A.; Tasiou, M.; Torrisi, G. On the Methodological Framework of Composite Indices: A Review of the Issues of Weighting, Aggregation, and Robustness. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 141, 61–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: A review and recent developments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, L.; Rousseeuw, P.J. Finding Groups in Data: An Introduction to Cluster Analysis; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-471-73578-6. [Google Scholar]

- Nardo, M.; Saisana, M.; Saltelli, A.; Tarantola, S.; Hoffman, A.; Giovannini, E. Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators and User Guide; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2008; ISBN 978-92-64-04345-9. [Google Scholar]

- Duro, J.A.; Osorio, A.; Perez-Laborda, A.; Fernández-Fernández, M. Measuring tourism markets vulnerability across destinations using composite indexes. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 25, 100731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linca, A.-C.; Toma, E. Study regarding the evolution of mountain tourism and rural mountain tourism in Romanian Carpathians. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2021, 21, 463–470. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, A. A statistical overview on the agrotourist guesthouses versus tourist guesthouses of the county of Sibiu, Romania. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2018, 18, 347–358. [Google Scholar]

- Toader, I.-A.; Mocuta, D. A study on agritourism services in Romania. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2018, 18, 475–482. [Google Scholar]

- Aleksandrov, K. A management model for sustainable development of the tourist destination. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2013, 13, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mateoc-Sîrb, N.; Mateoc, T.; Mănescu, C.; Cristina, A.-F.; Goșa, C.; Grad, I. A socio-economic analysis of the rural area in the Western Region. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2014, 14, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, A. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Romania’s tourist flows in the year 2020. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2021, 21, 655–666. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, A.; Marcuta, A.; Marcuta, L.; Tindeche, C. Trends in Romania’s tourism demand and offer in the mountain resorts during the period 2010–2019. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2021, 21, 623–636. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).