Rethinking Economic Foundations for Sustainable Development: A Comprehensive Assessment of Six Economic Paradigms Against the SDGs

Abstract

1. Introduction

Since the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in 1972, the global community has adopted a wealth of Multilateral Environmental Agreements as well as other relevant commitments, including the SDGs and the 2030 Agenda. Fulfillment of the objectives and commitments of all these agreements would take us a long way towards securing a healthy planet for all.Key recommendation for accelerating action towards a healthy planet for the prosperity of all, Stockholm + 50 Presidents Final Remarks to Plenary [2].

- (1)

- reveals which paradigm better aligns with sustainable development objectives;

- (2)

- identifies specific strengths and weaknesses across different sustainability dimensions for each paradigm;

- (3)

- provides the first academic exploration comparing alternative paradigms against all 17 SDGs;

- (4)

- bridges economic theory and sustainable development practice;

- (5)

- offers valuable insights for policymakers seeking economic approaches more compatible with achieving the 2030 Agenda.

2. Methodology

- Step 1: Systematic Characterization of Economic Paradigms

- Paradigmatic goals (normative intent);

- Economic system structure;

- Key actors;

- Elements of a functional economic system;

- Other relevant aspects.

- Step 2: Systematic Assessment Against SDGs

- 0 = SDG objective not addressed (no mention in core literature);

- 1 = Indirectly covers SDG-related objectives (mentioned but not central);

- 2 = Directly covers SDG-related objectives but uses a different approach;

- 3 = Directly covers SDG-related objectives using a similar framework.

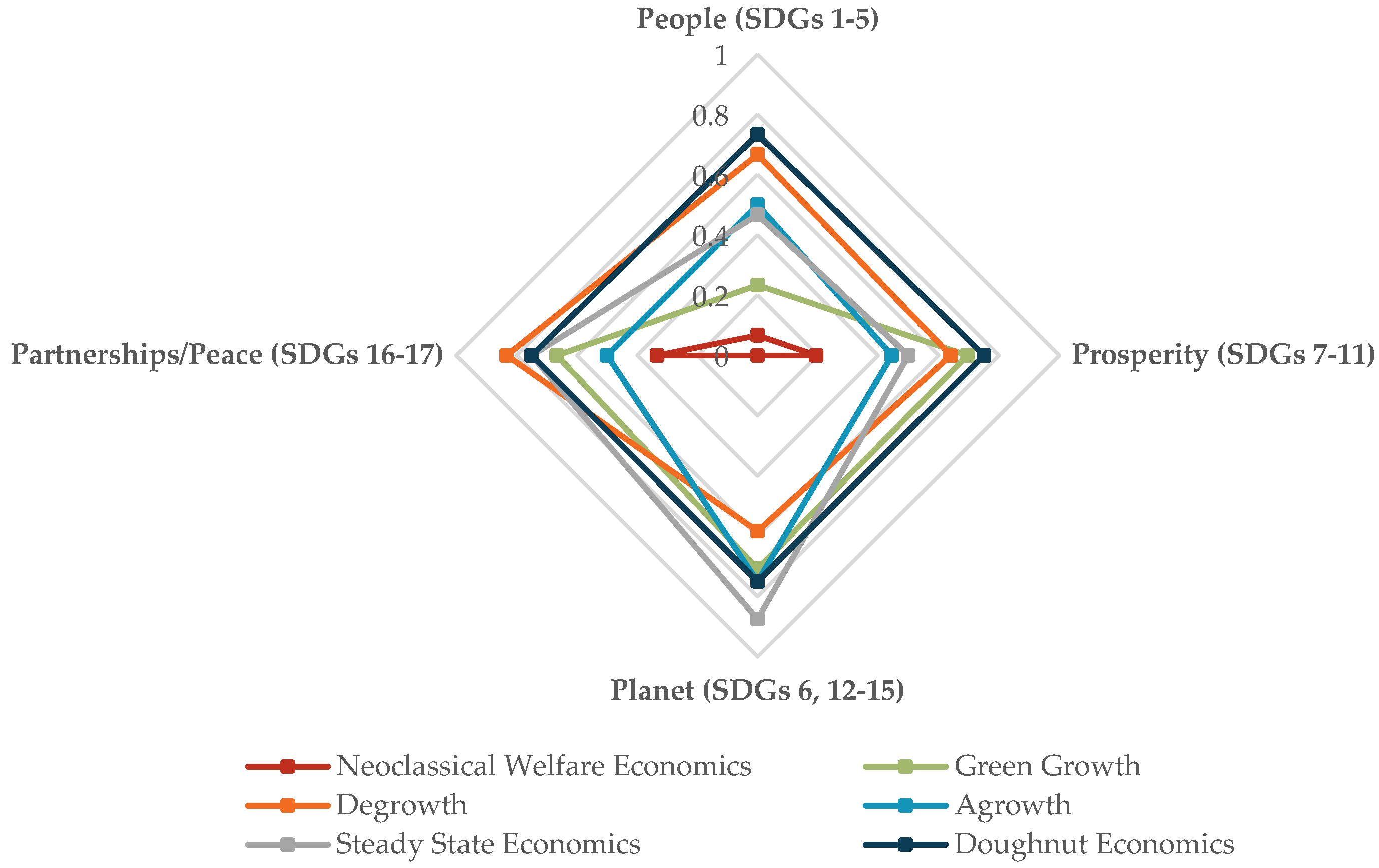

- People (SDGs 1–5);

- Planet (SDGs 6, 12–15);

- Prosperity (SDGs 7–11);

- Partnerships/Peace (SDGs 16–17).

- Methodological Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

3. Overview of Economic Paradigms

3.1. Neoclassical Welfare Economics

3.2. Green Growth

3.3. Degrowth

3.4. Agrowth

3.5. Steady State Economics

3.6. Doughnut Economics

3.7. Summary

| Attribute | Neoclassical Welfare Economics | Green Growth | Degrowth | Agrowth | Steady State Economics | Doughnut Economics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key sources | [33,34] | [7,44,45,46,47,48] | [56,66,67] | [77,79,80,81] | [54,88,93,94] | [90] |

| Paradigmatic goal(s) (or normative intent) | To make the market work more efficiently; allocate scarce resources (i.e., labor, capital, property, natural resources, etc.) in a way that leads to greater social welfare, defined by maximizing individual utility and producer profits. | Views economic growth as a critical component to reducing poverty, but aims for growth to be “decoupled” from ecological degradation and pursued in an equitable way | To reduce the environmental impact of human activities, redistribute income and wealth both within and between countries, transition from a materialistic society to one that is convivial and participatory | To focus on social and environmental welfare rather than GDP growth; pursues strong climate action | An economy without continuous growth in population and capital (either negative or positive) and one that remains within the regenerative and assimilative capacity of the ecosystem in the present and future. | Staying within a ‘safe and just space for humanity’ through population stabilization, redistribution of resources, greater connection and relationships over materialism, technological innovation, and good governance across all scales |

| Economic system | Market economy driven by capitalists (private owners) | Market economy driven by capitalists but actively corrects market failures through market-based instruments and strengthened regulatory frameworks | “mostly small, highly self-sufficient local economies; economic systems under social control … and highly cooperative and participatory systems” | Market-based with government interventions | Market-based but with greater regulatory oversight and reimagining | Market but with greater distribution and regeneration |

| Key actors in the economic system | Market participants (consumers and producers); government intervention only when necessary (laissez faire) | Market participants (consumers, producers), government (enabling environment, innovation) | Community, civil society, households, government, local businesses | Market, government (e.g., global climate agreements, market instruments, birth taxes, work time reduction, regulate advertisements) | Government (enact regulation, market-based instruments), communities, markets | Household, market, commons, state |

| Elements of a functional economic system | Continued economic growth for social welfare (utility, profits). Market failures corrected with market instruments. | Continued economic growth but with greater resource efficiency (“absolute decoupling”) | Autonomy, sufficiency, and care. End goal is a steady state economy. | Meets social and environmental goals and indicators | “optimum level of population and artifacts”, but focus on stability, not growth. Optimality depends on living standards, resource use, population, time period, and technology, where maximizing any one factor has its own set of tradeoffs. | |

| Other aspects | Commodifies environmental assets | Rejects growth; achieved by “disaccumulation”, “decommodification”, and “decolonization”, careful planning, democratic and participatory process; alternative development pathways | Agnostic to growth | Growth required in low-income economies | Agnostic to growth | |

| Keywords | Market goods, market efficiency, market failures and externalities, resource allocation, utility maximization, profit maximization, economic growth, laissez faire | Resource efficiency, economic growth, environmental decoupling, poverty reduction, equitable growth, inclusive growth, correcting market failures, green economy, green goods, green bads | Downsized economy, ecological compatibility, reduce consumption, sufficiency, redistribution, convivial, participatory, local economy, community, autonomy, democracy, care | Growth agnostic, depolarize growth, social welfare, environmental welfare, indicators, market instruments, global agreements, work time reduction, advertising regulation, population growth reduction, birth taxes | Without growth, stability, optimality, regenerative, market reimagining, market restructuring, local economies, population stabilization, capital stabilization | Ecological ceiling, planetary boundaries, social foundation, growth agnostic, redistributive, regenerative, dematerialism, circular economy, resource efficiency, technological innovation, governance, population stabilization, connections, care |

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Paradigm-SDG Alignment Overview

| SDGs | Welfare Economics | Green Growth | Degrowth | Agrowth | Steady State | Doughnut Economics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| People | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 2 | 0 | 1.5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1.5 | |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.5 | 1 | 1.5 | |

| 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| Prosperity | 7 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.5 | 3 |

| 8 | 1.5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1.5 | 1.5 | |

| 9 | 1 | 3 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 3 | |

| 10 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1.5 | 3 | 3 | |

| 11 | 0 | 1.5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1.5 | |

| Planet | 6 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| 12 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| 13 | 0 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | |

| 14 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| 15 | 0 | 1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 3 | 1.5 | |

| Partnerships & Peace | 16 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1.5 | 3 |

| 17 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1.5 | |

| Total score | 6.5 | 28.5 | 33.5 | 27.5 | 31 | 38 | |

| Neoclassical Welfare Economics | Green Growth | Degrowth | Agrowth | Steady State | Doughnut Economics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key sources 1 | [33,34] | [7,44,45,46,47,48] | [56,66,67] | [77,79,80,81] | [54,88,93,94] | [90] |

| People | Theorizes that utility is increased through economic growth, indirectly reducing poverty. Hunger, health, education, and gender equality are not addressed. | Like welfare economics, believes economic growth indirectly reduces poverty. Promotes training and education for a green economy. | Poverty reduction through redistribution of wealth and income. | Robust indicators of social welfare, including health, happiness, leisure, equity, environmental quality, and labor (including informal care work). Promotes population control policies. | Advocates for poverty reduction through minimum and maximum income limits. Family planning and reproductive justice (for population control). | Seeks minimum social foundations for decent living, including food, water, housing, health, energy, education, jobs and equality. |

| Prosperity | Pursues economic growth to maximize utility and profits. Market-based instruments are used to facilitate innovation and industrialization, but sustainability is not guaranteed. Inequality not addressed by market. | Encourages green innovation, technologies, and jobs. Pursues economic growth to reduce poverty. | Rejects economic growth for social welfare. Community-centric with more sharing. Inequality reduction through redistribution of wealth and income within and between countries. Flexible labor, valuing care, and informal labor. | Agnostic to economic growth. Encourages green innovation, technologies, and jobs. Prioritizes reduced work hours and greater leisure time. | Proposes stable growth in developed countries as opposed to continuous positive or negative growth. Pursues economic growth in developing countries to reduce poverty. Inequality reduction through minimum and maximum income limits. Internalize externalities through the market. | Aspire for relationships and connections over materialism. Agnostic to economic growth. Promotes technological innovation for a regenerative economy. Seeks distribution of income and resources to reduce inequality. Focus on commons. |

| Planet | Values social welfare (anthropocentric). Does not pursue environmental protection. Instead, economic growth leads to degradation. These externalities are not reflected in prices. | Encourages green innovation, technologies, and jobs to decouple growth from environmental degradation. Views ecosystem services and natural capital as commodities. | Aims to reduce environmental impact of human activities by transitioning away from materialism towards sufficiency. | Primary focus is on environmental protection. Rejects status consumption. | Encourages physical materials approach to resource use (i.e., depletion quotas), resulting in no to little degradation. | Explicit ecological ceiling before planetary degradation occurs, such as climate change or biodiversity loss. Community-based governance over commons, and dematerialism. |

| Partnerships and Peace | Existing global trade partnerships. | Environmental agreements and partnerships. | Transition to a convivial and participatory society. Democratic decision-making. | Aims for global climate agreements (such as the Paris Agreement). | Promotes localization and overhaul of the global financial system. Reduce monopolies and income inequalities for peace and better representation. | Minimum social foundations for justice and a political voice. Good governance. Decrease unfair trade and globalization. |

4.2. Comparing Paradigms Across Sustainable Development Dimensions

- Growth Orientation

- Environmental Protection Mechanisms

- Equity Considerations

- Governance Scales and Structures

4.3. Challenges and Gaps in Economic Paradigms and SDGs

4.4. Implications for Sustainable Development Theory and Practice

- Theoretical Implications

- Policy Integration and Complementarity

- Ecological boundaries and resource management: Steady State and Doughnut Economics provide robust frameworks for establishing absolute resource limits and ecological boundaries, addressing what Richardson et al. [87] identify as critical planetary boundaries now being transgressed.

- Social equity and redistribution mechanisms: Degrowth and Doughnut Economics offer the strongest frameworks for addressing inequality, aligning with growing evidence from Piketty [113] and others that inequality reduction is essential for both social and environmental sustainability.

- Innovation and efficiency improvements: Green Growth and Agrowth provide valuable approaches to technological innovation and efficiency, which, while insufficient alone, remain necessary components of sustainability transitions as documented by the IPCC [114].

- Implementation Pathways

5. Conclusions

- Develop integrated assessment frameworks that combine complementary strengths from multiple economic paradigms, particularly addressing current gaps in social dimensions and extending approaches pioneered by Costanza et al. [119].

- Establish experimental policy zones for testing alternative economic approaches, implementing concrete policy packages combining resource caps (from Steady State Economics), redistribution mechanisms (from Degrowth), and green innovation incentives (from Green Growth).

- Reform economics education to incorporate diverse economic paradigms, addressing the narrow orthodoxy critiqued by Raworth [90] and expanding the conceptual toolkit available to future policymakers.

- Develop context-specific transition pathways, recognizing that high-income countries may need to focus on consumption reduction (Degrowth elements), while low-income countries might prioritize basic needs fulfillment through resource-efficient development (combining Green Growth and Doughnut Economics approaches).

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Stockholm+50 Presidents. Presidents’ Final Remarks to Plenary: Key recommendations for accelerating action towards a healthy planet for the prosperity of all. In Proceedings of the Stockholm+50, Stockholm, Sweden, 2–3 June 2022; Available online: http://www.stockholm50.global/presidents-final-remarks-plenary-key-recommendations-accelerating-action-towards-healthy-planet (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- UN. Report of the Secretary-General on SDG Progress 2019; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/24978Report_of_the_SG_on_SDG_Progress_2019.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2023).

- UN DESA. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023; UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2023.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Bendell, J. Replacing Sustainable Development: Potential Frameworks for International Cooperation in an Era of Increasing Crises and Disasters. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN DESA. June 2023 Monthly Briefing on the World Economic Situtation and Prospects: Prospects for a Robust Global Recovery Remain Dim; UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/MB172.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2023).

- UNEP. Toward a Green Economy: Pathways to Sustainable Development and Poverty Eradication—A Synthesis for Policy Makers; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2011; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/126GER_synthesis_en.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Fisher, J.; Arora, P.; Chen, S.; Rhee, S.; Blaine, T.; Simangan, D. Four propositions on integrated sustainability: Toward a theoretical framework to understand the environment, peace, and sustainability nexus. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 1125–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biermann, F.; Hickmann, T.; Sénit, C.-A.; Beisheim, M.; Bernstein, S.; Chasek, P.; Grob, L.; Kim, R.E.; Kotzé, L.J.; Nilsson, M.; et al. Scientific evidence on the political impact of the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberl, H.; Wiedenhofer, D.; Virág, D.; Kalt, G.; Plank, B.; Brockway, P.; Fishman, T.; Hausknost, D.; Krausmann, F.; Leon-Gruchalski, B.; et al. A systematic review of the evidence on decoupling of GDP, resource use and GHG emissions, part II: Synthesizing the insights. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 065003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrique, T.; Barth, J.; Briens, F.; Kerschner, C.; Kraus-Polk, A.; Kuokkanen, A.; Spangenberg, J.H. Decoupling Debunked: Evidence and Arguments Against Green Growth as a Sole Strategy for Sustainability; European Environmental Bureau: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://gaiageld.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/decoupling_debunked_evidence_and_argumen.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2023).

- Vadén, T.; Lähde, V.; Majava, A.; Järvensivu, P.; Toivanen, T.; Hakala, E.; Eronen, J.T. Decoupling for ecological sustainability: A categorisation and review of research literature. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 112, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnedahl, K.J.; Heikkurinen, P.; Paavola, J. Strongly sustainable development goals: Overcoming distances constraining responsible action. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 129, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammelt, C.F.; Gupta, J. Inclusive is not an adjective, it transforms development: A post-growth interpretation of Inclusive Development. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 124, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, E.; Nazareth, A.; Kartha, S.; Kemp-Benedict, E. The Missing Link between Inequality and the Environment in SDG 10. In Transitioning to Reduced Inequalities; Bieri, S., Bader, C., Eds.; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuso Nerini, F.; Tomei, J.; To, L.S.; Bisaga, I.; Parikh, P.; Black, M.; Borrion, A.; Spataru, C.; Castán Broto, V.; Anandarajah, G.; et al. Mapping synergies and trade-offs between energy and the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPrete Brown, L.; Atapattu, S.; Stull, V.J.; Calderón, C.I.; Huambachano, M.; Houénou, M.J.P.; Snider, A.; Monzón, A. From a Three-Legged Stool to a Three-Dimensional World: Integrating Rights, Gender and Indigenous Knowledge into Sustainability Practice and Law. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S.-M.; Muhr, M.M.; Kirchner, M.; Toth, W.; Germann, V.; Hundscheid, L.; Vacik, H.; Scherz, M.; Kreiner, H.; Fehr, F.; et al. Handling a complex agenda: A review and assessment of methods to analyse SDG entity interactions. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 131, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Azorin, J.F. Mixed methods research: An opportunity to improve our studies and our research skills. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2016, 25, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.; Gardner, T.A.; Bennett, E.M.; Balvanera, P.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.; Daw, T.; Folke, C.; Hill, R.; Hughes, T.P.; et al. Advancing sustainability through mainstreaming a social-ecological systems perspective. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, D.J.; Wiek, A.; Bergmann, M.; Stauffacher, M.; Martens, P.; Moll, P.; Swilling, M.; Thomas, C.J. Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: Practice, principles, and challenges. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petticrew, M.; Roberts, H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide, 1st ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, M.; Griggs, D.; Visbeck, M. Policy: Map the interactions between Sustainable Development Goals. Nature 2016, 534, 320–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroll, C.; Warchold, A.; Pradhan, P. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Are we successful in turning trade-offs into synergies? Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SDG.SERVICES. When Did the Sustainability Principles Begin?: Learning About the Sustainability Leadership Principles; SDGS WEBSITE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20240724060114/https://www.sdg.services/principles.html (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, A. Degrowth, postdevelopment, and transitions: A preliminary conversation. Sustain. Sci. 2015, 10, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, A.; Salleh, A.; Escobar, A.; Demaria, F.; Acosta, A. (Eds.) Pluriverse: A Post-Development Dictionary; Tulika Books and Authorsupfront: Delhi, India, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ramazzotti, P. Heterodoxy, the Mainstream and Policy. J. Econ. Issues 2022, 56, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroey, M.D.; Pensieroso, L. The Rise of a Mainstream in Economics; UCLouvain: Toulouse, France, 2016; Available online: https://ideas.repec.org//p/ctl/louvir/2016026.html (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Hirai, T. A balancing act between economic growth and sustainable development: Historical trajectory through the lens of development indicators. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 1900–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, F. Introduction to welfare economics. Public Choice 2018, 177, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graaff, J.D.V. Theoretical Welfare Economics; Cambridge Univ. Pr.: Cambridge, UK, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Harsanyi, J.C. Cardinal Welfare, Individualistic Ethics, and Interpersonal Comparisons of Utility. J. Polit. Econ. 1955, 63, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, D.Z. “Welfare without the welfare state”: Milton Friedman’s negative income tax and the monetization of poverty. Mod. Intellect. Hist. 2023, 20, 934–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florio, M. Applied Welfare Economics, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowdy, J.M. The Revolution in Welfare Economics and Its Implications for Environmental Valuation and Policy. Land Econ. 2004, 80, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makowski, L.; Ostroy, J.M. Perfect Competition and the Creativity of the Market. J. Econ. Lit. 2001, 39, 479–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandmo, A. The Early History of Environmental Economics. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2015, 9, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, A.; Dawes, L.; Costanza, R.; Kubiszewski, I. Evaluation of social externalities in regional communities affected by coal seam gas projects: A case study from Southeast Queensland. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 131, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y.-K. From preference to happiness: Towards a more complete welfare economics. Soc. Choice Welf. 2003, 20, 307–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Collective Choice and Social Welfare; an expanded edition; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Inclusive Green Growth: The Pathway to Sustainable Development; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Declaration on Green Growth; OECD: Paris, France, 2009; Available online: http://www.oecd.org/env/44077822.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- OECD. Towards Green Growth; OECD: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Towards Green Growth: Monitoring Progress: OECD Indicators; OECD: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Inclusive Green Growth: For the Future We Want; OECD: Paris, France, 2012; p. 48. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/greengrowth/Rio+20%20brochure%20FINAL%20ENGLISH%20web%202.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- Hoffmann, U. Can Green Growth Really Work and What are the True (Socio-) Economics of Climate Change? United Nations University: Tokyo, Japan, 2015; Volume 222, p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Hickel, J.; Kallis, G. Is Green Growth Possible? New Polit. Econ. 2020, 25, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, G.; Mathai, M.V.; Puppim de Oliveira, J.A. (Eds.) Green Growth: Ideology, Political Economy and the Alternatives; Zed Books: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Paoli, L.; Cullen, J. Technical limits for energy conversion efficiency. Energy 2020, 192, 116228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockway, P.E.; Sorrell, S.; Semieniuk, G.; Heun, M.K.; Court, V. Energy efficiency and economy-wide rebound effects: A review of the evidence and its implications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 141, 110781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, H.E. Steady-State Economics, 2nd ed.; with new essays; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hickel, J.; Dorninger, C.; Wieland, H.; Suwandi, I. Imperialist appropriation in the world economy: Drain from the global South through unequal exchange, 1990–2015. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2022, 73, 102467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrique, T. The Political Economy of Degrowth. Ph.D. Thesis, University Clermont Auvergne, Clermont-Ferrand, France, 2019. Available online: https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02499463/document (accessed on 6 July 2021).

- Ridoux, N. La Décroissance Pour Tous; Parangon-Vs: Lyon, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kallis, G. In defence of degrowth. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallis, G. Degrowth; Agenda Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, F.; Kallis, G.; Martinez-Alier, J. Crisis or opportunity? Economic degrowth for social equity and ecological sustainability. Introduction to this special issue. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Alier, J.; Pascual, U.; Vivien, F.-D.; Zaccai, E. Sustainable de-growth: Mapping the context, criticisms and future prospects of an emergent paradigm. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1741–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceddia, M.G.; Montani, R.; Mioni, W. The dialectics of capital: Learning from Gran Chaco. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 17, 2347–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchs, M.; Koch, M. Postgrowth and Wellbeing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alisa, G.; Demaria, F.; Kallis, G. (Eds.) Degrowth: A Vocabulary for a New Era; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: Florence, KY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Demaria, F.; Schneider, F.; Sekulova, F.; Martinez-Alier, J. What is Degrowth? From an Activist Slogan to a Social Movement. Environ. Values 2013, 22, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosme, I.; Santos, R.; O’Neill, D.W. Assessing the degrowth discourse: A review and analysis of academic degrowth policy proposals. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, N.; Parrique, T.; Cosme, I. Exploring degrowth policy proposals: A systematic mapping with thematic synthesis. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asara, V.; Otero, I.; Demaria, F.; Corbera, E. Socially sustainable degrowth as a social-ecological transformation: Repoliticizing sustainability. Sustain. Sci. 2015, 10, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trainer, T. On degrowth strategy: The Simpler Way perspective. Environ. Values 2024, 33, 394–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulos, T. Is Degrowth Compatible with a Market Economy? Incl. Democr. 2007, 3, 1. Available online: https://www.inclusivedemocracy.org/journal/vol3/vol3_no1_Takis_degrowth.htm (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Hickel, J. What does degrowth mean? A few points of clarification. Globalizations 2021, 18, 1105–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, A.; Demaria, F.; Acosta, A. Buen Vivir, Degrowth and Ecological Swaraj: Alternatives to sustainable development and the Green Economy. Development 2014, 57, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latouche, S. Farewell to Growth; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lenaerts, K.; Tagliapietra, S.; Wolff, G.B. The Global Quest for Green Growth: An Economic Policy Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. Prosperity Without Growth: Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Boillat, S.; Gerber, J.-F.; Funes-Monzote, F.R. What economic democracy for degrowth? Some comments on the contribution of socialist models and Cuban agroecology. Futures 2012, 44, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bergh, J.C.J.M. Environment versus growth—A criticism of “degrowth” and a plea for “a-growth”. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergh, J.C.J.M.V.D. The GDP paradox. J. Econ. Psychol. 2009, 30, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bergh, J.C.J.M.; Kallis, G. Growth, a-growth or degrowth to stay within planetary boundaries? J. Econ. Issues 2012, 46, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bergh, J.C.J.M. A third option for climate policy within potential limits to growth. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2017, 7, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bergh, J.C.J.M. Agrowth instead of anti- and pro-growth: Less polarization, more support for sustainability/climate policies. J. Popul. Sustain. 2018, 3, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, H.E.; Cobb, J.B. For the Common Good: Redirecting the Economy Toward Community, the Environment, and a Sustainable Future, 2nd ed.; updated and expanded; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts, J.; O’Neill, B.C. Global warming policy: Is population left out in the cold? Science 2018, 361, 650–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartha, S.; Kemp-Benedict, E.; Ghosh, E.; Nazareth, A.; Gore, T. The Carbon Inequality Era: An Assessment of the Global Distribution of Consumption Emissions Among Individuals from 1990 to 2015 and Beyond; Stockholm Environment Institute and Oxfam Sweden: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020; Available online: https://www.sei.org/publications/the-carbon-inequality-era/ (accessed on 8 August 2021).

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S., III; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; de Vries, W.; de Wit, C.A.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347, 6223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, K.; Steffen, W.; Lucht, W.; Bendtsen, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Donges, J.F.; Drüke, M.; Fetzer, I.; Bala, G.; von Bloh, W.; et al. Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadh2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASSE. CASSE’s Top 15 Policies for Achieving a Steady State Economy; Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://steadystate.org/discover/policies/ (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- Philips, L. The Degrowth Delusion; OpenDemocracy: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/oureconomy/degrowth-delusion/ (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Raworth, K. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Raworth, K. A Safe and Just Space for Humanity; Oxfam: Oxford, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www-cdn.oxfam.org/s3fs-public/file_attachments/dp-a-safe-and-just-space-for-humanity-130212-en_5.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Spash, C.L. Apologists for growth: Passive revolutionaries in a passive revolution. Globalizations 2020, 18, 1123–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, H.E. Moving From a Failed Growth Economy to a Steady-State Economy. In Towards an Integrated Paradigm in Heterodox Economics: Alternative Approaches to the Current Eco-Social Crises; Gerber, J.-F., Steppacher, R., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2012; pp. 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, H.E. Steady-State Economics: A New Paradigm. New Lit. Hist. 1993, 24, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickel, J. Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, D.W.; Fanning, A.L.; Lamb, W.F.; Steinberger, J.K. A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanning, A.L.; O’Neill, D.W.; Hickel, J.; Roux, N. The social shortfall and ecological overshoot of nations. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Common, M.; Stagl, S. Ecological Economics: An Introduction, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedmann, T.; Allen, C. City footprints and SDGs provide untapped potential for assessing city sustainability. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Development As Freedom; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J.E.; Sen, A.; Fitoussi, J.-P. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. 2009. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/8131721/8131772/Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi-Commission-report.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Hickel, J. Quantifying National Responsibility for Climate Breakdown: An Equality-Based Attribution Approach for Carbon dioxide Emissions in Excess of the Planetary Boundary. Lancet 2020, 4, E399–E404. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(20)30196-0/fulltext (accessed on 9 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, R.G.; Pickett, K. The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better; Allen Lane: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dorling Danny, D. The Equality Effect, 1st ed.; New Internationalist Publications, Limited: La Vergne, TN, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 641–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F. Earth System Governance: World Politics in the Anthropocene; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, J.; Leininger, J. Governing the Interlinkages between the Sustainable Development Goals: Approaches to Attain Policy Integration. Glob. Chall. 2017, 1, 1700036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, J.W. The Rise of Cheap Nature. In Anthropocene or Capitalocene; Moore, J.W., Ed.; PM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 78–115. Available online: https://jasonwmoore.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Moore-Rise-of-Cheap-Nature-Anth-or-Cap-volume-2016.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Stirling, A. Multicriteria diversity analysis. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 1622–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Blanc, D. Towards Integration at Last? The Sustainable Development Goals as a Network of Targets. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 23, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadowcroft, J. What about the politics? Sustainable development, transition management, and long term energy transitions. Policy Sci. 2009, 42, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K. Is the 1.5 °C target possible? Exploring the three spheres of transformation. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 31, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piketty, T. Capital in the Twenty-First Century; The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. In Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Göpel, M. The Great Mindshift; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buch-Hansen, H. The Prerequisites for a Degrowth Paradigm Shift: Insights from Critical Political Economy. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 146, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausknost, D.; Hammond, M. Beyond the environmental state? The political prospects of a sustainability transformation. Environ. Polit. 2020, 29, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I.; Stirling, A.; Abrol, D.; Atela, J.; Charli-Joseph, L.; Eakin, H.; Ely, A.; Olsson, P.; Pereira, L.; Priya, R.; et al. Transformations to sustainability: Combining structural, systemic and enabling approaches. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 42, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; Daly, L.; Fioramonti, L.; Giovannini, E.; Kubiszewski, I.; Mortensen, L.F.; Pickett, K.E.; Ragnarsdottir, K.V.; De Vogli, R.; Wilkinson, R. Modelling and measuring sustainable wellbeing in connection with the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 130, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ghosh, E.; Pearson, L.J. Rethinking Economic Foundations for Sustainable Development: A Comprehensive Assessment of Six Economic Paradigms Against the SDGs. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4567. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104567

Ghosh E, Pearson LJ. Rethinking Economic Foundations for Sustainable Development: A Comprehensive Assessment of Six Economic Paradigms Against the SDGs. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4567. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104567

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhosh, Emily, and Leonie J. Pearson. 2025. "Rethinking Economic Foundations for Sustainable Development: A Comprehensive Assessment of Six Economic Paradigms Against the SDGs" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4567. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104567

APA StyleGhosh, E., & Pearson, L. J. (2025). Rethinking Economic Foundations for Sustainable Development: A Comprehensive Assessment of Six Economic Paradigms Against the SDGs. Sustainability, 17(10), 4567. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104567