How Community Engagement Approach Enhances Heritage Conservation: Two Case Studies on Sustainable Urban Development in Historic Cairo

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Community Engagement

“A community [is] a number of people who share a distinct location, belief, interest, activity, or other characteristic that clearly identifies their commonality and which differentiates them from those who do not share it” [12].

“Since the 1980s stakeholder involvement has been declared as the most effective strategy to ensure a balanced socio-economic and political-cultural development for structurally weak regions” [11].

2.2. Types of Community Engagement: From Tokenism to Empowerment

- (1)

- Tokenistic Involvement: Tokenistic involvement means that the opinions of some people are simply sought so that their participation can be shown, but those opinions and desires are ignored. Or the planning agencies simply look for public consensus on certain predetermined approaches. Planned society participation in regional spatial planning of Southern Cross Road area in Malang East Java, Indonesia, is generally still at the level of placation and tokenism [19]. Community members are informed about decisions but have little real influence. Participation is symbolic rather than meaningful.

- (2)

- Consultative Approach: Authorities seek public opinions through surveys and meetings, but final decisions rest with officials. The consultative approach should be distinguished from the much weaker informational model of community participation. The latter has no community representation on the decision-making body, and community members are typically informed of the decision only after it is made. Consultative approaches allow for feedback from the community in coming to a decision. Expert decision-makers control the process, but they genuinely attempt to solicit input from the community and to consider it in decision-making [20].

- (3)

- Collaborative/Community-Led: The residents actively shape projects and share responsibility for planning, implementation and management. This is defined as an abstract representation of some object or process that helps us understand it better. Three main community participation models in decision making that have been studied or proposed in the literature are functionalist, interpretative and realist models. Functionalist models of community participation focus primarily on the advantages of public participation for expert decision-making and the task of officials to gain community input [21].

- (4)

- Creative Engagement: Creative engagement goes beyond awareness-raising and education efforts. Engagement activities that are just sharing information with the public or collect public input are valuable, but these more traditional approaches to community engagement are not described as having an artistic character. These types of efforts often fall short of involving the community members in meaningful, co-creative processes to shape outcomes. In this way, they resemble public relations or marketing tactics much more than creative practices with a vital role in community capacity-building and resilience. In contrast, the creative engagement methods highlighted in these case studies engage the public in ways that produce meaning and ideas are co-produced, rather than transmitted or collected [21]. These use artistic, interactive and innovative methods such as storytelling, exhibitions and performances to involve communities.

- (5)

- Higher Education-Led: Information provided by higher education (IHEs) is transformed by the evolving policy process into a means for the development of potential new regulatory frameworks for private, non-profit higher education institutions. This transformation does not result from direct persuasion but rather takes place through processes of elaboration that political elites undertake to distinguish their own position in a way that allows them to consider it to be plausible and relevant to public discussion/generations of legitimacy [22]. Universities and academic institutions lead research-driven projects and provide technical and historical expertise, as shown in Table 1.

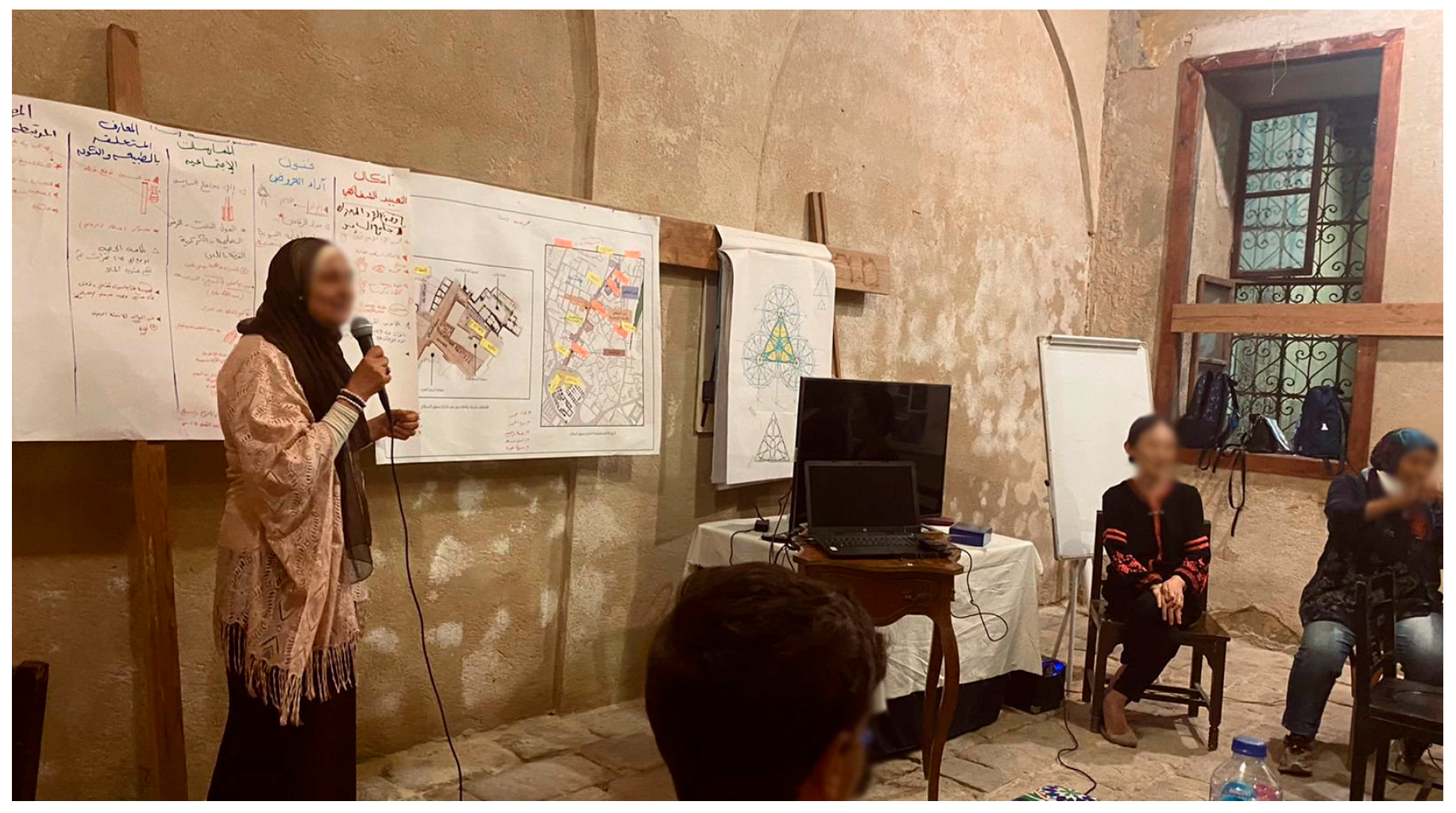

| Date | Workshop Num. | Workshop Topic | Number of Facilitators | Number of Men | Ages Range of Men | Numbers of Women | Ages Range of Women | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26 June 2022 | 1 | Traffic in Al-darb Al-Ahmar, its problems and solutions | 6 | 8 | 35–50 | 13 | 30–45 | 1. Improve traffic management and infrastructure. 2. Enhance street safety and cleanliness. 3. Beautify the area with trees and lighting. 4. Utilize resources like empty lands and shopping carts. 5. Create a pedestrian-friendly and organized environment. |

| 21 August 2022 | 3 | Risk management in Al-Darb Al-Ahmar, Historic Cairo | 8 | 13 | 35–50 | 16 | 30–45 | 1. Upgrade infrastructure for safety and fire prevention. 2. Convert vacant lands into gardens and improve waste management. 3. Renovate streets and public spaces for emergencies. 4. Use schools and mosques as refuge points. 5. Raise awareness and reduce risks from utilities and factories. |

| 23 October 2022 | 5 | Intangible Heritage Souq Al-Silah, how to connect it with historical architecture | 7 | 8 | 35–50 | 9 | 30–45 | 1. Oral Traditions: Proverbs, stories, superstitions, and transportation signs. 2. Performing Arts: Traditional dances, instruments, and Mawlid shows. 3. Social Practices: Popular foods, cultural habits, and rituals. 4. Nature Customs: Practices linked to nature for good fortune. 5. Craft Skills: Traditional arts like Khayamiya, arabesques, and copperwork. |

| 18 December 2022 | 7 | Traditional crafts in the Al-Darb Al-Ahmar area | 6 | 18 | 35–50 | 10 | 30–45 | 1. Challenges: High costs, loss of crafts, and lack of support. 2. Solutions: Provide training, create exhibitions, and establish a trade union. 3. Awareness & Education: Promote crafts via media and schools. 4. Monitoring: Track artisans through a craft record. |

- (a)

- Active Community Role: Residents were not just consulted but engaged in planning, decision-making and implementation.

- (b)

- Workshops and Training: Locals participated in skill-building sessions to understand conservation techniques.

- (c)

- Participatory Planning: Community members contributed ideas, helping shape rehabilitation efforts to reflect their needs.

- (d)

- Sense of Ownership: Residents became stakeholders, ensuring long-term sustainability beyond project completion.

- (e)

- Combining Local and Expert Knowledge: Traditional craftsmanship and historical insights were integrated with expert conservation strategies.

- (f)

- Sustainable Impact: The approach fostered economic and social benefits while maintaining cultural authenticity.

2.3. Phases of Community Engagement Process

2.4. Tools of Community Engagement

3. Case Studies Background

3.1. Historical and Cultural Significance of Al-Darb Al-Ahmar Heritage Site

3.2. Overview of the Urban Regeneration Project for Historic Cairo (URHC)

3.3. Overview of the JSPS Project (Japan Society for the Promotion of Science): Project for Sustainable Conservation in the Historic Cairo/Community Development with the Participation of Local Residents

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Design

- (A)

- Theoretical Development: A literature review synthesizes frameworks for community engagement, including types and tools of community engagement. This informs the analysis framework for the evaluation the two case studies to explore a community engagement tool for sustainable urban development.

- (B)

- Case Study Analysis: A detailed analysis and examination of the URHC and JSPS projects, focusing on their community engagement tool processes, tools and outcomes.

- (C)

- Synthesis and Comparison: Synthesis of the findings to respond to the research questions, comparing engagement strategy effectiveness between the two projects.

4.2. Community Engagement Process

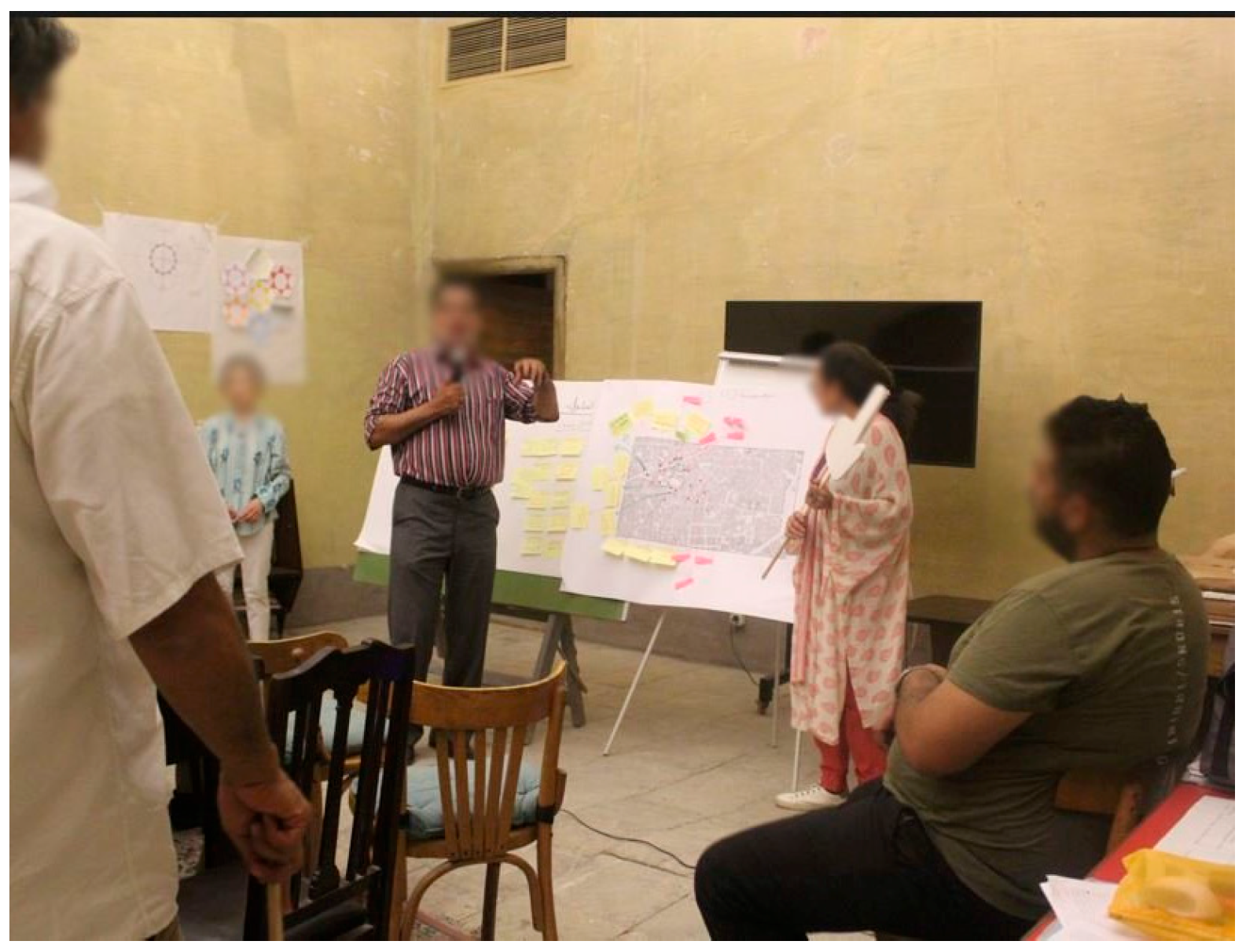

4.2.1. Project 1: Urban Regeneration Project for Historic Cairo (URHC) (Al-Darb Al-Ahmar Housing Rehabilitation Program, Cairo, Egypt

- (1)

- Emergency and Pilot Phase (2001–2004): Community and requirements of community heritage were initially discovered through surveys and workshops. Community mapping, involving around 50 residents, documented building conditions and open green spaces, as per UNESCO’s HUL toolkit of community [5].

- (2)

- Preparation Phase (2005–2008): Capacity-building workshops and community meetings engaged 200 residents, consisting of craft and home owners, to develop a master plan. Facilitators who were trained by Aga Khan Trust assisted in communication between residents and government representatives, as recommended by Sanoff [35].

- (3)

- Implementation Phase (2009–present): Co-designed action projects, such as housing rehabilitation and monument restoration, were undertaken in collaboration with the community. Over 430 residents participated in quantitative surveys and 10 focus groups conducted participatory mapping to refine conservation methods.

- Building and Open Space Inventories:

- Training Manuals:

- Pilot Projects:

- In-Depth Analyses:

- Monitoringand Intervention:

- Awareness Initiatives:

- Public Outreach

4.2.2. Project 2 Process of (Community Engagement): JSPS PROJECT (Japan Society for the Promotion of Science): Project for Sustainable Conservation in the Historic Cairo/Community Development with the Participation of Local Residents

4.3. Data Collection

4.4. Data Analysis

4.5. Ethical Considerations

4.6. Validity and Reliability

4.7. Justification of Methodological Decisions

4.8. Limitations

5. Results

5.1. Community Participation Levels

5.2. Types of Engagement Tools Used

5.3. Adaptive Reuse for Long-Term Sustainability

5.4. Comparative Overview

6. Discussion

6.1. The Role of Community Engagement in Sustainable Urban Development

6.2. Key Strategies for Effective Community Engagement

- (a)

- Workshops and Training Sessions: The URHC trained around 200 local residents in conservation techniques and urban planning principles with the help of facilitators, while the JSPS provided eight workshops, and these align with UNESCO’s HUL toolkit.

- (b)

- Participatory Planning and Decision-Making: This enabled local residents to propose and refine conservation initiatives in collaboration with facilitators and stakeholder meetings.

- (c)

- Cultural and Economic Revitalization: This involved promoting heritage tourism, local crafts and entrepreneurship to sustain conservation efforts in heritage areas. The URHC’s microfinance for 50 businesses and the JSPS’s cultural events for 500 visitors (Section 4) promoted heritage tourism, as advocated by Sanoff [35].

6.3. Challenges and Opportunities for Improvement

7. Limitations

- (a)

- Improve legal frameworks and systems to protect and more successfully help effectively save places.

- (b)

- Create creative digital interaction tools to encourage public involvement.

- (c)

- Enhance systems of financial assistance for nearby companies and artists.

- (1)

- Apply mixed-method approaches to combine qualitative depth with statistical robustness.

- (2)

- Expand the geographic scope to include comparative projects in other Middle Eastern or international urban historical sites.

- (3)

- Examine new digital engagement tools and their effectiveness in heritage contexts in a sustainable way.

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Saffar, M. Sustainable Urban Heritage: Assessing Baghdad’s Historic Centre of Old Rusafa. Architecture 2024, 4, 71–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatis, S. Designing with Communities: A Framework for a Collaborative Public Engagement Process; Herron School of Art and Design: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bruley, E.; Locatelli, B.; Lavorel, S. Nature’s Contributions to People: Coproducing Quality of Life from Multifunctional Landscapes. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H. Perceived Social Impacts of Tourism and Quality-of-Life: A New Conceptual Model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 5, 445–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. World Heritage City Lab; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Angrisano, M.; Biancamano, P.F.; Bosone, M.; Carone, P.; Daldanise, G.; De Rosa, F.; Franciosa, A.; Gravagnuolo, A.; Iodice, S.; Nocca, F. Towards Operationalizing UNESCO Recommendations on “Historic Urban Landscape”. In Proceedings of International Symposium; Firenze University Press: Florence, Italy, 2017; pp. 165–210. [Google Scholar]

- Dogruyol, Y.A.K.; Zeynep, A. Eye of Sustainable Planning: A Conceptual Heritage-Led Urban Regeneration Planning Framework. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderland, N.; Muirhead, G.; Parsons, R.; Holtom, D. The Australian Consortium on Higher Education, Community Engagement and Social Responsibility; The Australian Consortium for Higher Education: Brisbane, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Selim, A.A.; El-Sharkawy, E.S. The Revitalization of Endangered Heritage Buildings: A Decision-Making Framework for Investment and Determining the Highest and Best Use in Egypt. Natl. Libr. Med. 2023, 12, 874. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Records of the General Conference; UNESCO Digital Library: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alhadad, E.F. The Contribution of Community Involvement in Heritage Management: A Cultural Mapping Project. Master’s Thesis, Brandenburg University of Technology Cottbus–Senftenberg, Cottbus, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Naidoo, L. The Participatory Development Communication Approach of Thusong Service. Master’s Thesis, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aga Khan Trust for Culture. Urban Regeneration in the Darb Al-Ahmar District; Aga Khan Trust for Culture: Cairo, Egypt, 2005; Available online: https://static.the.akdn/53832/1641875850-2005_aktc_cairo_regeneration.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- Ibrahim, K. Housing Rehabilitation Study; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Cairo, Egypt, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H.Y.; Yao, L. Exploring the Contribution of Advanced Systems in Smart City Development for the Regeneration of Urban Industrial Heritage. Buildings 2024, 14, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aga Khan Trust for Culture. The Cultural Agency of the Aga Khan Development Network; Aga Khan Trust for Culture: Cairo, Egypt, 2007; Available online: https://static.the.akdn/53832/1641873562-2007_aktc.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2024).

- Serrano-Estrada, L.; Bañón, Á.; Hernández, M.L. Mapping Heritage Engagement in Historic Centres through Social Media Insights and Accessibility Analysis. Land 2024, 13, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, A.F.A.; Ahmed, A. Participatory Local Governance for Sustainable Community Development, Approaches and Actions (Al-Muizz Street: Analytical Study). J. High. Inst. Qual. Stud. 2022, 2, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suphattanakul, O. Public Participation in Decision-Making Processes: Concepts and Tools. J. Bus. Soc. Rev. Emerg. Econ. 2018, 4, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runnels, V.; Coyle, A. Community-Based Research Decision-Making: Experiences and Factors Affecting Participation. Int. J. Community Res. Engagem. 2013, 6, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragouni-Minaa, F.K.; Giannikos, G.N. Community Participation in Heritage Tourism Planning: Is It Too Much to Ask? UCL Inst. Sustain. Herit. 2017, 26, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer, B.C.D.; Walker, S.B. Connecting General Education Programming with Regionally-Engaged Learning Economies: The Results of a Community Inquiry and Dialogue. J. Reg. Engagem. 2015, 4, 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sukri, S. Community Engagement: A Case Study on the Four Ethnic Groups in Melaka, Malaysia: World Heritage City. Ph.D. Thesis, University of York, York, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rashed, H. Sustainable Urban Development in Historic Cairo. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK, 2013; pp. 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gravagnuolo, A.; Angrisano, M. A Participatory Approach for “Circular” Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage: Building a Heritage Community in Salerno, Italy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukami, A.E.H. Souq Al-Silah Workshops; JSPS: Cairo, Egypt, 2023; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/canopy/cairo/ (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- MAbdel Aty Mohamed, A.; Ali Gammaz, S. Assessment of the Role of International Organizations in the Rehabilitation of Historic Districts: Case of Darb Al-Ahmar. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2012, 138, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerwill, L.; Wehn, U. How to Measure the Impact of Citizen Science on Environmental Attitudes, Behaviour and Knowledge? A Review of State-of-the-Art Approaches. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2022, 34, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Elbes, E.K.; Oktaviani, L. Character Building in English for Daily Conversation Class Materials for English Education Freshmen Students. J. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2022, 3, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizami, Z.T.; Sulaiman, K.N.A. Innovative Pedagogical Principles and Technological Tools Capabilities for Immersive Blended Learning: A Systematic Literature Review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 1373–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkadi, H.; Al-Maiyah, S. Daylight for Sustainable Development of Historic Sites. Perform. Ecol. Built Environ. 2009, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Elshahed, M. Facades of Modernity: Image, Performance, and Transformation in the Egyptian Metropolis. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- URHC. Study on the Violations: Urban Regeneration Project for Historic Cairo; URHC: Cairo, Egypt, 2014; Available online: https://www.urhcproject.org/Studies (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Alaa El-Habashy, N.F. A Community Development with the Participation of Local Residents; JSPS Cairo Research Station: Cairo, Egypt, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sanoff, H. Community Participation Methods in Design and Planning; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Forester, J. The Deliberative Practitioner: Encouraging Participatory Planning Processes; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, J.S.L.; Eaton, D.A.; Alm, A.M.A. Assessing Participatory Practices in Community-Based Natural Resource Management: Experiences in Community Engagement from Southern Africa. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 137, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazi, Y.S.; Sabry, A.-F.M.F.; Nasser, E.-A.N. Socio-Spatial Vulnerability Assessment of Heritage Buildings through Using Space Syntax. Natl. Libr. Med. 2022, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, B.D.D. Socially Innovative Frameworks for Socioeconomic Resilience in Urban Design. In International Conference for Sustainable Design of the Built Environment SDBE 2018; University of Strathclyde: Glasgow, UK, 2018; pp. 1034–1036. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ibrashy, M. URHC Community Outreach Component; UNESCO: Cairo, Egypt, 2013; Available online: https://www.urhcproject.org/Content/studies/13_al_ibrashy.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2023).

- Ansary, M.A.-I.C. Study Area Report on Intangible Heritage and Storytelling; UNESCO: Cairo, Egypt, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies; Macmillan: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fukami, A.E.H. Toward the Future of Souq al Silah; JSPS: Cairo, Egypt, 2022; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/activities/documents/activity-1087-28.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, M. Public Places, Urban Spaces; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.H.; Hong, S.C.; Lee, Y. Top-Down, Bottom-Up, or Both? Toward an Integrative Perspective on Operations Strategy Formation. J. Oper. Manag. 2014, 32, 463–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, Q.-H. The Semiconducting Principle of Monetary and Environmental Values Exchange. Econ. Bus. Lett. 2021, 10, 286–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camangian, S.C.P. Social and Emotional Learning Is Hegemonic Miseducation: Students Deserve Humanization Instead. Race Ethn. Educ. 2022, 25, 901–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, B. The Terracotta Temple of Antpur: An Attempt to Study the Importance of Heritage Management. Soc. Herit. Archaeol. Manag. 2021, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Jagtap, S. Co-Design with Marginalized People: Designers’ Perceptions of Barriers and Enablers. CoDesign 2022, 17, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sendra, P. The Ethics of Co-Design. J. Urban Des. 2024, 29, 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, L.R.; Maharjan, M.R. Community Engagement in Post-Earthquake Nepal: Lessons from Bhaktapur. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2017, 23, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.T.R.; Manandhar, M.P. Sustainable Restoration Practices in Heritage Sites: Bhaktapur as a Case Study. Kathmandu Univ. Press 2019, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Thapa, R.K. Integrating Traditional Building Techniques in Urban Development: A Bhaktapur Perspective. J. Urban Herit. 2018, 12, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Shurbaji, M.H. Urban Regeneration of Old Doha in Qatar: Towards the Implementation of Historic Urban Landscape Approach. Master’s Thesis, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar, 2008. [Google Scholar]

| Key Themes | Project 1: URHC (Al-Darb Al-Ahmar) | Project 2: JSPS (Souq El-Silah) |

|---|---|---|

| Legal and Planning Framework. | Strengthened urban conservation policies. | Integrated legal reforms into planning decisions. |

| Community Engagement level. | High engagement in planning and decision-making. | Gradual increase due to cultural initiatives. |

| Engagement Tools. | Workshops, mapping and public meetings. | Workshops, public meetings, participatory mapping and documentation. |

| Community Engagement. | Stakeholders, local residents and facilitators | Stakeholders, local residents and facilitators |

| Main Challenges. | Weak enforcement, financial constraints. | Funding shortages, planning integration issues. |

| Urban Impact. | Restored homes, improved the economy and infrastructure. | Strengthened tourism, revitalized crafts and public space enhancement. |

| Economic Sustainability. | Supported artisans, heritage tourism and microfinance. | Linked conservation with craft businesses and tourism. |

| Intangible Heritage. | Focused on physical restoration. | Focused on physical restoration and cultural heritage sustainable preservation (tangible and intangible) preservation. |

| Cultural Preservation. | Focused on adaptive reuse of historic buildings. | Emphasized preservation of tangible and intangible heritage. |

| Monitoring and Evaluation. | Limited ongoing assessment. | Continuous community-led evaluation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fahmy, A.; Thamarat, M. How Community Engagement Approach Enhances Heritage Conservation: Two Case Studies on Sustainable Urban Development in Historic Cairo. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4565. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104565

Fahmy A, Thamarat M. How Community Engagement Approach Enhances Heritage Conservation: Two Case Studies on Sustainable Urban Development in Historic Cairo. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4565. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104565

Chicago/Turabian StyleFahmy, Amgad, and Mariam Thamarat. 2025. "How Community Engagement Approach Enhances Heritage Conservation: Two Case Studies on Sustainable Urban Development in Historic Cairo" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4565. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104565

APA StyleFahmy, A., & Thamarat, M. (2025). How Community Engagement Approach Enhances Heritage Conservation: Two Case Studies on Sustainable Urban Development in Historic Cairo. Sustainability, 17(10), 4565. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104565