Scientists’ Views on Sustainable Healthy Diets: A Reflection Process Towards a Multi-Disciplinary Consensus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Delphi Method and Its Application to Sustainable Food Systems

2.2. Participants on the Delphi Panel

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Aspects of Sustainable Healthy Eating

3.2. Obstacles to Promoting Health and Sustainable Food in Spain

3.3. Action to Promote Healthy and Sustainable Eating in Spain

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Methodological Implications

5.2. Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| DIMENSIONS | SCORE BY DISCIPLINE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural Sciences | Natural Sciences | Health Sciences | Social Sciences | ||

| 1 | Safe and secure | 13.67 | 14.33 | 11.50 | 12.52 |

| 2 | Balance between the actors in the food system | 8.00 | 9.83 | 9.00 | 9.32 |

| 3 | Reduction and optimisation of food waste | 9.67 | 12.67 | 9.08 | 9.84 |

| 4 | Based on nutritious food ensuring optimal state of health | 15.17 | 17.50 | 15.83 | 13.32 |

| 5 | Local or short-supply chain | 8.00 | 4.83 | 9.50 | 9.24 |

| 6 | Based on organic food | 9.33 | 5.67 | 5.83 | 7.04 |

| 7 | Socially appropriate and culturally acceptable | 9.33 | 3.67 | 9.50 | 9.64 |

| 8 | Low presence of animal protein | 3.17 | 6.50 | 10.08 | 8.36 |

| 9 | Low environmental and climate impact | 15.67 | 13.17 | 13.17 | 13.24 |

| 10 | Low level of processing | 7.33 | 7.83 | 10.33 | 9.12 |

| 11 | Respect for workers’ rights. health. and safety | 10.50 | 11.00 | 9.50 | 9.6 |

| 12 | Affordable | 8.17 | 12.00 | 10.00 | 11.24 |

| 13 | Reduced presence of pesticides and antibiotics | 15.17 | 7.17 | 7.33 | 8.16 |

| 14 | Fair remuneration for food producers | 10.67 | 10.50 | 8.92 | 9.04 |

| 15 | Available and accessible | 9.33 | 12.50 | 11.83 | 11.32 |

| 16 | Participation of different actors in food governance processes | 6.17 | 5.83 | 6.67 | 6.44 |

| 17 | Minimal packaging. reduced presence of plastic in packaging | 6.00 | 9.00 | 6.25 | 7.4 |

| 18 | High animal welfare standards | 5.67 | 7.00 | 6.67 | 6.16 |

| BARRIERS | SCORE BY DISCIPLINE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural Sciences | Natural Sciences | Health Sciences | Social Sciences | ||

| 1 | The presence of global crises (pandemics, wars, etc.) is slowing down the transition to sustainable and healthy food models. | 5.17 | 4.67 | 4.58 | 6.46 |

| 2 | Information on food and the food system is limited, confusing, and inaccurate. | 12.17 | 9.00 | 8.58 | 9.23 |

| 3 | Externalities (positive and negative) are not incorporated into food prices. | 10.17 | 8.00 | 9.42 | 11.69 |

| 4 | Poor communication and coordination between scientific disciplines working on sustainable and healthy diets. | 9.83 | 8.17 | 9.92 | 6.15 |

| 5 | With respect to food, the ‘sustainable’ and ‘healthy’ aspects tend to be treated separately. | 7.17 | 10.00 | 7.33 | 9.00 |

| 6 | Poor regulation of unsustainable and unhealthy food, and lack of enforcement measures. | 10.17 | 10.00 | 13.50 | 11.77 |

| 7 | Measures to promote sustainable and healthy food centre on individual consumer choices. | 8.17 | 11.50 | 12.67 | 11.15 |

| 8 | Priority is given to the health dimension in recommendations and measures on food, leaving aside the environmental or social justice dimensions. | 9.00 | 7.67 | 7.92 | 10.15 |

| 9 | Poor integration of the views, measures, and actors working on food. | 9.83 | 8.00 | 10.83 | 7.85 |

| 10 | There is no specific body dedicated to promoting sustainable and healthy diets. | 6.67 | 8.50 | 8.92 | 7.00 |

| 11 | Lack of political ambition to implement effective measures to promote sustainable and healthy food. | 12.33 | 13.33 | 15.33 | 12.00 |

| 12 | There is insufficient dissemination and transfer of research results on sustainable and healthy food. | 7.33 | 9.83 | 6.92 | 7.85 |

| 13 | Sustainable and healthy food is not accessible and affordable for a significant portion of the population | 11.50 | 13.17 | 11.58 | 11.31 |

| 14 | Strong influence of the food industry and large-scale distribution on the organisation of production, distribution, purchasing habits, and food policies. | 16.33 | 12.50 | 16.08 | 15.00 |

| 15 | Initiatives to promote sustainable and healthy food promoted by citizens and social organisations are co-opted by the dominant system. | 10.00 | 9.17 | 9.83 | 8.62 |

| 16 | The level of food education of the public is low. | 9.33 | 14.33 | 6.50 | 10.00 |

| 17 | Primacy of urban needs over rural needs | 7.83 | 8.17 | 5.00 | 8.23 |

| 18 | The export-oriented nature of the Spanish agri-food sector and dependence on third countries for imported food. | 8.00 | 5.00 | 6.08 | 7.54 |

| INITIATIVES IN THE AREA OF TRAINING, EDUCATION, AND SCIENCE | SCORE BY DISCIPLINE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural Sciences | Natural Sciences | Health Sciences | Social Sciences | ||

| 1 | Encourage a change in the system of values regarding food to prioritise people’s health and the health of the planet. | 6.17 | 7.83 | 7.50 | 7.31 |

| 2 | Promote effective legislation/regulation of food information in labelling and/or advertising. | 6.83 | 5.33 | 7.08 | 7.00 |

| 3 | Provide sufficient, verified, and accurate information on food and the food system. | 7.17 | 7.00 | 5.42 | 6.92 |

| 4 | Promote the coordination and integration of the different scientific disciplines working on sustainable and healthy food. | 5.83 | 4.50 | 5.50 | 5.15 |

| 5 | Promote a cross-cutting food education for all citizens. | 4.67 | 8.83 | 5.67 | 7.31 |

| 6 | Create a specific logo to distinguish sustainable and healthy foods. | 2.33 | 3.00 | 4.17 | 4.31 |

| 7 | Enhance the role of nutritionists in schools and introduce nutritionists in public health services. | 3.67 | 5.67 | 5.50 | 3.77 |

| 8 | Strengthen the socio-cultural and environmental dimension in food research and recommendations to consumers. | 5.00 | 4.00 | 5.42 | 5.46 |

| 9 | Improve accessibility to the results of research on sustainable and healthy food and promote its dissemination among the public. | 6.00 | 5.17 | 4.83 | 3.54 |

| 10 | Promote knowledge and appreciation of the rural environment and the agri-food system. | 7.33 | 3.67 | 3.92 | 4.23 |

| INITIATIVES IN VARIOUS ASPECTS OF THE FOOD SYSTEM | SCORE BY DISCIPLINE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural Sciences | Natural Sciences | Health Sciences | Social Sciences | ||

| 1 | Establish measures to make sustainable and healthy food accessible and affordable for all citizens. | 7.33 | 10.00 | 9.83 | 8.77 |

| 2 | Monitor and follow up existing measures to promote sustainable and healthy food (e.g., PAOS, campaigns against food waste, self-regulation of food advertising, etc.). | 4.00 | 5.17 | 4.75 | 4.08 |

| 3 | Tax unhealthy foods with a high environmental impact. | 5.50 | 5.17 | 6.17 | 6.38 |

| 4 | Promote the agroecological transition of production systems. | 7.17 | 3.00 | 7.58 | 6.62 |

| 5 | Design a territorial model to reduce depopulation and maintain agricultural activity. | 4.83 | 4.67 | 3.92 | 6.08 |

| 6 | Promote and reappraise local, artisanal, and organic agri-food production. | 7.83 | 5.00 | 5.42 | 5.69 |

| 7 | Implement measures to encourage the consumption of sustainable and healthy foods. | 5.83 | 9.00 | 8.08 | 7.08 |

| 8 | Generate market opportunities so that the different actors in the food system can move towards sustainable and healthy food models. | 6.00 | 5.00 | 4.92 | 5.69 |

| 9 | Orient agri-food companies’ Corporate Social Responsibility action towards sustainable and healthy food. | 5.00 | 6.17 | 3.83 | 3.08 |

| 10 | Promote short food supply chains and local trade. | 5.50 | 6.17 | 4.92 | 5.77 |

| 11 | Encourage public procurement of sustainable and healthy food in public institutions (hospitals, schools, care homes, prisons, etc.). | 7.00 | 6.67 | 6.58 | 6.77 |

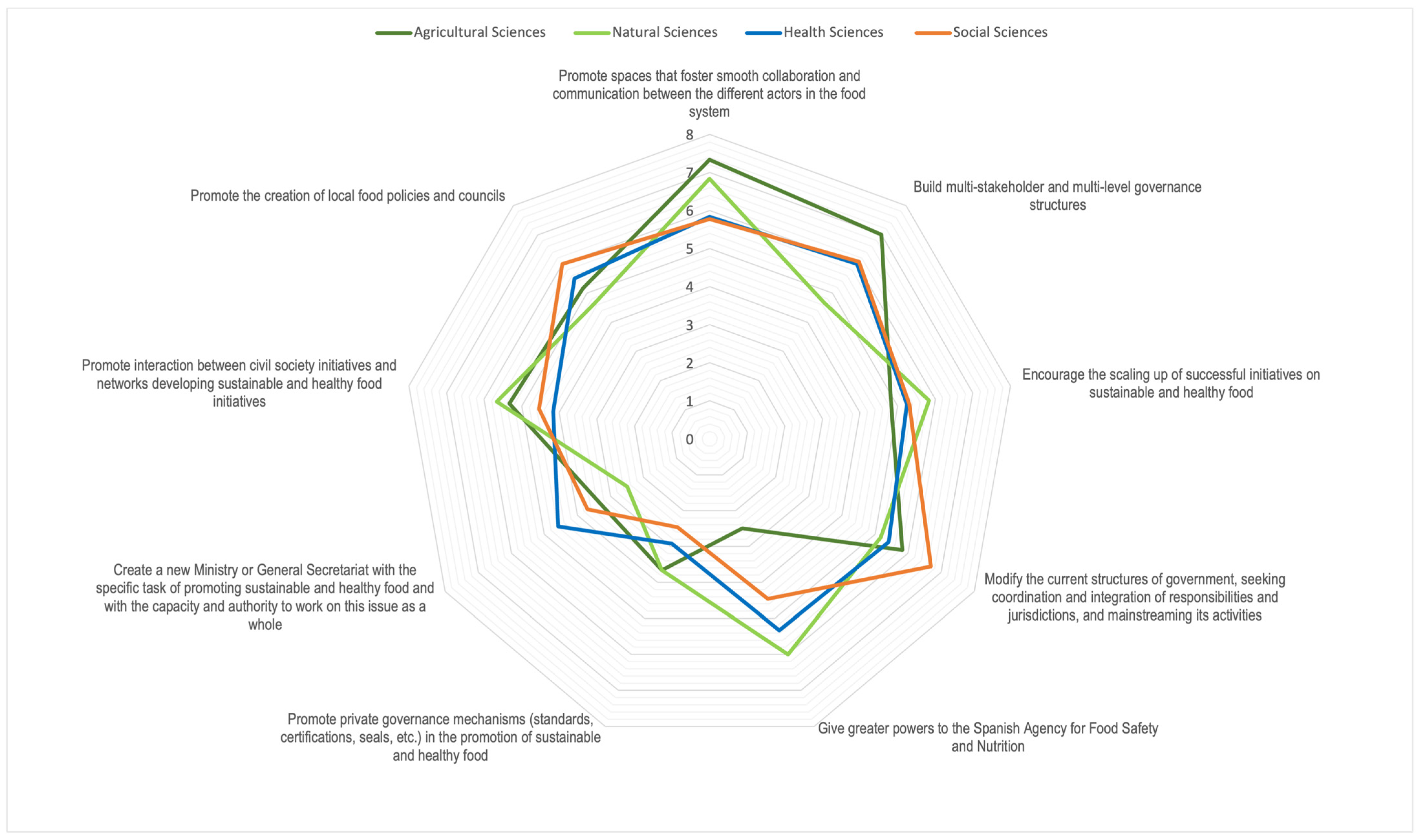

| INITIATIVES IN THE AREA OF GOVERNANCE AND THE FRAMEWORK OF RELATIONS BETWEEN ACTORS WITHIN THE FOOD SYSTEM | SCORE BY DISCIPLINE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural Sciences | Natural Sciences | Health Sciences | Social Sciences | ||

| 1 | Promote spaces that foster smooth collaboration and communication between the different actors in the food system. | 7.33 | 6.83 | 5.83 | 5.77 |

| 2 | Build multi-stakeholder and multi-level governance structures. | 7.00 | 4.67 | 6.00 | 6.08 |

| 3 | Encourage the scaling up of successful initiatives on sustainable and healthy food. | 4.83 | 5.83 | 5.25 | 5.31 |

| 4 | Modify the current structures of government, seeking coordination and integration of responsibilities and jurisdictions, and mainstreaming its activities. | 5.83 | 5.17 | 5.42 | 6.69 |

| 5 | Give greater powers to the Spanish Agency for Food Safety and Nutrition. | 2.50 | 6.00 | 5.33 | 4.46 |

| 6 | Promote private governance mechanisms (standards, certifications, seals, etc.) in the promotion of sustainable and healthy food. | 3.67 | 3.67 | 2.92 | 2.46 |

| 7 | Create a new Ministry or General Secretariat with the specific task of promoting sustainable and healthy food and with the capacity and authority to work on this issue as a whole. | 3.33 | 2.50 | 4.58 | 3.69 |

| 8 | Promote interaction between civil society initiatives and networks developing sustainable and healthy food initiatives. | 5.33 | 5.67 | 4.17 | 4.54 |

| 9 | Promote the creation of local food policies and councils. | 5.17 | 4.67 | 5.50 | 6.00 |

References

- Clark, M.; Tilman, D. Comparative Analysis of Environmental Impacts of Agricultural Production Systems, Agricultural Input Efficiency, and Food Choice. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 064016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Kraak, V.I.; Allender, S.; Atkins, V.J.; Baker, P.I.; Bogard, J.R.; Brinsden, H.; Calvillo, A.; De Schutter, O.; Devarajan, R.; et al. The Global Syndemic of Obesity, Undernutrition, and Climate Change: The Lancet Commission Report. Lancet 2019, 393, 791–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Méndez, C.; Ramos-Truchero, G. From the Economic Crisis to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain: The Challenges for Healthy Eating in Times of Crisis. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2023, 31, 100655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023. Urbanization, Agrifood Systems Transformation and Healthy Diets across the Rural–Urban Continuum; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Farré-Ribes, M.; Lozano-Cabedo, C.; Aguilar-Criado, E. The Role of Knowledge in Constructing the Quality of Olive Oil in Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, F.X. Towards a Construction of the Mediterranean Diet? The Building of a Concept between Health, Sustainability and Culture. Food Ethics 2021, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Towards a Sustainable Food System. Moving from Food as a Commodity to Food as More of a Common Good; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, M.R.; Palma, G.; Buendia, T.; Bueno-Tarodo, M.; Quell, D.; Hachem, F. A Scoping Review of Indicators for Sustainable Healthy Diets. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 5, 822263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, T.; Mason, P. Sustainable Diet Policy Development: Implications of Multi-Criteria and Other Approaches, 2008–2017. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2018, 77, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Transforming Food and Agriculture to Achieve the SGDs. 20 Interconnected Actions to Guide Decision-Makers; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Garnett, T. What Is a Sustainable Healthy Diet? A Discussion Paper; Food Climate Research Network: Oxford, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, T. The Sustainable Diet Question: Reasserting Societal Dynamics into the Debate about a Good Diet. Int. J. Sociol. Agric. Food 2021, 27, 12–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Special Eurobarometer 505: Making Our Food Fit for the Future—Citizens’ Expectations (Special Eurobarometer 505—Wave EB93.2). Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2241 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Van Loo, E.J.; Hoefkens, C.; Verbeke, W. Healthy, Sustainable and Plant-Based Eating: Perceived (Mis)Match and Involvement-Based Consumer Segments as Targets for Future Policy. Food Policy 2017, 69, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boylan, S.; Sainsbury, E.; Thow, A.M.; Degeling, C.; Craven, L.; Stellmach, D.; Gill, T.P.; Zhang, Y. A Healthy, Sustainable and Safe Food System: Examining the Perceptions and Role of the Australian Policy Actor Using a Delphi Survey—CORRIGENDUM. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, T.; Prosperi, P.; Cogill, B.; Padilla, M.; Peri, I. A Delphi Approach to Develop Sustainable Food System Metrics. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 141, 1307–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; Drimie, S. Governance Arrangements for the Future Food System: Addressing Complexity in South Africa. Environment 2016, 58, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, T.; Horton, R. The 21st-Century Great Food Transformation. Lancet 2019, 393, 386–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Méndez, C.; Lozano-Cabedo, C. Food Governance and Healthy Diet an Analysis of the Conflicting Relationships among the Actors of the Agri-Food System. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 105, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béné, C.; Oosterveer, P.; Lamotte, L.; Brouwer, I.D.; de Haan, S.; Prager, S.D.; Talsma, E.F.; Khoury, C.K. When Food Systems Meet Sustainability—Current Narratives and Implications for Actions. World Dev. 2019, 113, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, J.; Drewnowski, A. Toward Sociocultural Indicators of Sustainable Healthy Diets. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, A.; Finley, J.; Hess, J.M.; Ingram, J.; Miller, G.; Peters, C. Toward Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beal, T.; Massiot, E.; Arsenault, J.E.; Smith, M.R.; Hijmans, R.J. Global Trends in Dietary Micronutrient Supplies and Estimated Prevalence of Inadequate Intakes. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Healthy Diet (Fact Sheet, 394). 2018. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/healthy-diet/healthy-diet-fact-sheet-394.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Little, J.; Ilbery, B.; Watts, D. Gender, Consumption and the Relocalisation of Food: A Research Agenda. Sociol Rural. 2009, 49, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Som Castellano, R.L. Alternative Food Networks and Food Provisioning as a Gendered Act. Agric. Hum. Values 2015, 32, 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, S.J.; Campbell, B.M.; Ingram, J.S.I. Climate Change and Food Systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2012, 37, 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Méndez, C.; Gómez-Benito, C. Nutrition and the Mediterranean Diet. A Historical and Sociological Analysis of the Concept of a “Healthy Diet” in Spanish Society. Food Policy 2010, 35, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulain, J.-P. Sociologies de l’alimentation. Les Mangeurs et l’espace Social Alimentaire. In Sociologies de L’alimentation; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, K. Reconnecting Farmers and Citizens in the Food System. In Visions of American Agriculture; Lockeretz, W., Ed.; Iowa State Press: Ames, IA, USA, 1997; pp. 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Cucurachi, S.; Scherer, L.; Guinée, J.; Tukker, A. Life Cycle Assessment of Food Systems. One Earth 2019, 1, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.; Prosperi, P. Modeling Sustainable Food Systems. Environ. Manag. 2016, 57, 956–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2013. Food Systems for Better Nutrition; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Diekmann, L.O.; Gray, L.C.; Baker, G.A. Growing ‘Good Food’: Urban Gardens, Culturally Acceptable Produce and Food Security. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2020, 35, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.D.; Hoey, L.; Blesh, J.; Miller, L.; Green, A.; Shapiro, L.F. A Systematic Review of the Measurement of Sustainable Diets. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 641–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamine, C.; Magda, D.; Amiot, M.J. Crossing Sociological, Ecological, and Nutritional Perspectives on Agrifood Systems Transitions: Towards a Transdisciplinary Territorial Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Lamine, C.; Allès, B.; Chiffoleau, Y.; Doré, A.; Dubuisson-Quellier, S.; Hannachi, M. The Key Roles of Economic and Social Organization and Producer and Consumer Behaviour towards a Health-Agriculture-Food-Environment Nexus: Recent Advances and Future Prospects. Rev. Agric. Food Environ. Stud. 2020, 101, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Löffler, F.; Sayler, G. Closing Transdisciplinary Collaboration Gaps of Food-Energy-Water Nexus Research. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 126, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; WHO. Sustainable Healthy Diets—Guiding Principles; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson, D.; Gutman, A.; Leet, W.; Drewnowski, A.; Fanzo, J.; Ingram, J. Seven Food System Metrics of Sustainable Nutrition Security. Sustainability 2016, 8, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moragues-Faus, A.; Sonnino, R.; Marsden, T. Exploring European Food System Vulnerabilities: Towards Integrated Food Security Governance. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 75, 184–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, J.; Claeys, P. Politicizing Food Security Governance through Participation: Opportunities and Opposition. Food Secur. 2018, 10, 1411–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernal, R.; San-Jose, L.; Retolaza, J.L. Improvement Actions for a More Social and Sustainable Public Procurement: A Delphi Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullerton, K.; Adams, J.; Francis, O.; Forouhi, N.; White, M. Building Consensus on Interactions between Population Health Researchers and the Food Industry: Two-Stage, Online, International Delphi Study and Stakeholder Survey. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, F.; Sonnino, R.; López Cifuentes, M. Connecting the Dots: Integrating Food Policies towards Food System Transformation. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 156, 103735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, V.; Linstone, H.A.; Turoff, M. The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications. J. Mark. Res. 1976, 13, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, U.G.; Clarke, R.E. Theory and Applications of the Delphi Technique: A Bibliography (1975–1994). Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 1996, 53, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangaratinam, S.; Redman, C.W. The Delphi Technique. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2005, 7, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.; Coveney, J.; Henderson, J.; Meyer, S.; Calnan, M.; Caraher, M.; Webb, T.; Elliott, A.; Ward, P. Trust Makers, Breakers and Brokers: Building Trust in the Australian Food System. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentholt, M.T.A.; Rowe, G.; König, A.; Marvin, H.J.P.; Frewer, L.J. The Views of Key Stakeholders on an Evolving Food Risk Governance Framework: Results from a Delphi Study. Food Policy 2009, 34, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, L.; Callaghan, E.; Broman, G. How Can Dietitians Leverage Change for Sustainable Food Systems in Canada? Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2019, 80, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, C.G.; Rampold, S.D. Urban Agriculture: Local Government Stakeholders’ Perspectives and Informational Needs. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2021, 36, 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssebunya, B.R.; Schmid, E.; Van Asten, P.; Schader, C.; Altenbuchner, C.; Stolze, M. Stakeholder Engagement in Prioritizing Sustainability Assessment Themes for Smallholder Coffee Production in Uganda. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2017, 32, 428–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daim, T.U.; Li, X.; Kim, J.; Simms, S. Evaluation of Energy Storage Technologies for Integration with Renewable Electricity: Quantifying Expert Opinions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2012, 3, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vio, F.; Olaya, M.; Fuentes-García, A.; Lera, L. Delphi Method to Reach Consensus on Education Methods to Promote Healthy Eating Behaviors in Adolescents. Nutr. Hosp. 2020, 37, 838–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oñederra-Aramendi, A.; Begiristain-Zubillaga, M.; Cuellar-Padilla, M. Characterisation of Food Governance for Alternative and Sustainable Food Systems: A Systematic Review. Agric. Food Econ. 2023, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disciplinary Areas | Experts Participating in Round 1 | Experts Participating in Rounds 2 and 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Sciences | 3 | 6 (15.78%) |

| Health Sciences | 2 | 12 (31.57%) |

| Agricultural Sciences | 2 | 6 (15.78%) |

| Social Sciences | 3 | 14 (36.84%) |

| Total | 10 | 38 (100%) |

| Item | DIMENSIONS OF A SUSTAINABLE HEALTHY DIET | Round 2 | Round 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | Based on nutritious food ensuring an optimal state of health | 13.89 | 14.00 |

| 9 | Low environmental and climate impact | 13.45 | 13.68 |

| 1 | Safe and secure | 13.13 | 13.13 |

| 15 | Available and accessible | 10.92 | 10.92 |

| 12 | Affordable | 10.97 | 10.87 |

| 11 | Respect for workers’ rights, health, and safety | 10.11 | 10.32 |

| 3 | Reduction and optimisation of food waste | 9.89 | 10.08 |

| 14 | Fair remuneration for food producers | 9.71 | 9.68 |

| 2 | Balance between actors in the food system | 9.42 | 9.34 |

| 13 | Reduced presence of pesticides and antibiotics | 9.32 | 9.21 |

| 7 | Socially appropriate and culturally acceptable | 8.74 | 8.63 |

| 10 | Low level of processing | 8.53 | 8.55 |

| 5 | Local or short supply chain | 8.26 | 8.45 |

| 6 | Based on organic food | 7.58 | 7.42 |

| 17 | Minimal packaging, reduced presence of plastic in packaging | 7.26 | 7.29 |

| 8 | Low presence of animal protein | 7.03 | 7.24 |

| 16 | Participation of different actors in food governance processes | 6.39 | 6.26 |

| 18 | High animal welfare standards | 6.39 | 6.10 |

| Item | BARRIERS TO THE PROMOTION OF HEALTHY AND SUSTAINABLE FOOD IN SPAIN | Round 2 | Round 3 |

| 14 | Strong influence of the food industry and large-scale distribution on the organisation of production, distribution, purchasing habits, and food policies | 15.08 | 15.11 |

| 11 | Lack of political ambition to implement effective measures to promote sustainable and healthy diets. | 13.42 | 13.42 |

| 6 | Poor regulation of unsustainable and unhealthy food, and lack of enforcement measures. | 11.89 | 11.92 |

| 13 | Sustainable and healthy food is not accessible and affordable for a significant portion of the population. | 11.76 | 11.82 |

| 7 | Measures to promote sustainable and healthy food centre on individual consumer choices. | 11.26 | 11.29 |

| 3 | Externalities (positive and negative) are not incorporated into food prices. | 10.24 | 10.32 |

| 16 | The level of food education of the public is low. | 9.68 | 9.50 |

| 2 | Information on food and the food system is limited, confusing, and inaccurate. | 9.53 | 9.47 |

| 15 | Initiatives to promote sustainable and healthy food promoted by citizens and social organisations are co-opted by the dominant system. | 9.53 | 9.39 |

| 9 | Poor integration of the views, measures, and actors working on food. | 8.97 | 9.03 |

| 8 | Priority is given to the health dimension in recommendations and measures on food, leaving aside the environmental and social justice dimensions. | 8.74 | 8.84 |

| 4 | Poor communication and coordination between the scientific disciplines working on sustainable and healthy diets. | 8.26 | 8.29 |

| 5 | With respect to food, the ‘sustainable’ and ‘healthy’ aspects tend to be treated separately. | 8.21 | 8.24 |

| 12 | There is insufficient dissemination and transfer of research results on sustainable and healthy food. | 8.13 | 7.79 |

| 10 | There is no specific body dedicated to promoting sustainable and healthy diets. | 7.76 | 7.79 |

| 17 | Primacy of urban over rural needs. | 6.97 | 7.00 |

| 18 | The export-oriented nature of the Spanish agri-food sector and dependence on third countries for imported food. | 6.32 | 6.58 |

| 1 | The presence of global crises (pandemics, wars, etc.) is slowing down the transition to sustainable and healthy food models. | 5.24 | 5.26 |

| Item | INITIATIVES TO PROMOTE HEALTHY AND SUSTAINABLE FOOD IN SPAIN IN THE FIELD OF TRAINING, EDUCATION, AND SCIENCE | Round 2 | Round 3 |

| 1 | Encourage a change in the system of values regarding food to prioritise people’s health and the health of the planet. | 7.29 | 7.29 |

| 2 | Promote effective legislation/regulation of food information in labelling and/or advertising. | 6.82 | 6.82 |

| 5 | Promote cross-cutting food education for all citizens. | 6.55 | 6.55 |

| 3 | Provide sufficient, verified, and accurate information on food and the food system. | 6.50 | 6.50 |

| 4 | Promote the coordination and integration of the different scientific disciplines working on sustainable and healthy food. | 5.16 | 5.16 |

| 8 | Strengthen the socio-cultural and environmental dimensions in food research and recommendations to consumers. | 5.11 | 5.11 |

| 7 | Enhance the role of nutritionists in schools and introduce nutritionists in public health services. | 4.66 | 4.66 |

| 9 | Improve accessibility to the results of research on sustainable and healthy food and promote its dissemination among the public. | 4.58 | 4.58 |

| 10 | Promote knowledge and appreciation of the rural environment and the agri-food system. | 4.47 | 4.47 |

| 6 | Create a specific logo to distinguish sustainable and healthy food. | 3.87 | 3.87 |

| Item | INITIATIVES TO PROMOTE HEALTHY AND SUSTAINABLE FOOD IN SPAIN BY PROMOTING CHANGES IN THE DIFFERENT DIMENSIONS OF THE FOOD SYSTEM | Round 2 | Round 3 |

| 1 | Establish measures to make sustainable and healthy food accessible and affordable for all citizens. | 9.03 | 9.00 |

| 7 | Implement measures to encourage the consumption of sustainable and healthy foods. | 7.55 | 7.61 |

| 11 | Encourage public procurement of sustainable and healthy food in public institutions (hospitals, schools, care homes, prisons, etc.). | 6.82 | 6.79 |

| 4 | Promote the agroecological transition of production systems. | 6.50 | 6.53 |

| 3 | Tax unhealthy foods with a high environmental impact. | 5.97 | 6.00 |

| 6 | Encourage and reappraise local, artisanal and organic food production. | 5.74 | 5.82 |

| 10 | Promote short food supply chains and local commerce. | 5.61 | 5.58 |

| 8 | Generate market opportunities so that the different actors in the food system can move towards sustainable and healthy food models. | 5.37 | 5.34 |

| 5 | Design a territorial model to reduce depopulation and maintain agricultural activity. | 4.92 | 4.87 |

| 2 | Monitor and follow up existing measures to promote sustainable and healthy food (e.g., PAOS campaigns against food waste, self-regulation of food advertising, etc.). | 4.42 | 4.42 |

| 9 | Orient agri-food companies’ Corporate Social Responsibility action of towards sustainable and healthy food. | 4.08 | 4.05 |

| Item | INITIATIVES TO PROMOTE HEALTHY AND SUSTAINABLE FOOD IN SPAIN IN THE FIELD OF GOVERNANCE AND THE FRAMEWORK OF RELATIONS BETWEEN ACTORS IN THE FOOD SYSTEM | Round 2 | Round 3 |

| 1 | Promote spaces that foster smooth collaboration and communication between the different actors in the food system. | 6.21 | 6.21 |

| 2 | Build multi-stakeholder and multi-level governance structures. | 5.95 | 5.95 |

| 4 | Modify the current structures of government, seeking coordination and integration of responsibilities and jurisdictions, and mainstreaming its activities. | 5.79 | 5.79 |

| 9 | Promote the creation of local food policies and councils. | 5.58 | 5.58 |

| 3 | Encourage the scaling up of successful initiatives on sustainable and healthy food. | 5.34 | 5.34 |

| 8 | Promote interaction between civil society initiatives and networks developing sustainable and healthy food initiatives. | 4.82 | 4.82 |

| 5 | Give greater powers to the Spanish Agency for Food Safety and Nutrition. | 4.58 | 4.58 |

| 7 | Create a new Ministry or General Secretariat with the specific task of promoting sustainable and healthy food and with the capacity and authority to work on this issue as a whole. | 3.71 | 3.71 |

| 6 | Promote private governance mechanisms (standards, certifications, seals, etc.) in the promotion of sustainable and healthy food. | 3.03 | 3.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lozano-Cabedo, C.; Moreno, M.; Díaz-Méndez, C.; Ajates, R.; Navas-Martín, M.Á. Scientists’ Views on Sustainable Healthy Diets: A Reflection Process Towards a Multi-Disciplinary Consensus. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4542. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104542

Lozano-Cabedo C, Moreno M, Díaz-Méndez C, Ajates R, Navas-Martín MÁ. Scientists’ Views on Sustainable Healthy Diets: A Reflection Process Towards a Multi-Disciplinary Consensus. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4542. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104542

Chicago/Turabian StyleLozano-Cabedo, Carmen, Marta Moreno, Cecilia Díaz-Méndez, Raquel Ajates, and Miguel Ángel Navas-Martín. 2025. "Scientists’ Views on Sustainable Healthy Diets: A Reflection Process Towards a Multi-Disciplinary Consensus" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4542. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104542

APA StyleLozano-Cabedo, C., Moreno, M., Díaz-Méndez, C., Ajates, R., & Navas-Martín, M. Á. (2025). Scientists’ Views on Sustainable Healthy Diets: A Reflection Process Towards a Multi-Disciplinary Consensus. Sustainability, 17(10), 4542. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104542