The Role of HRM Practices in Shaping a Positive Psychosocial Experience of Employees: Insights from the SCARF Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable HRM Practices

2.2. Exploring the Psychosocial Experiences of Employees Through the SCARF Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Context of the Study

3.2. Data Sample and Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

- Theme: main topic (SCARF, HRM practices).

- Category: a sub-group within the theme that represents a broader dimension (for instance, specific SCARF domain, specific HRM practice).

- Characteristic: specific attributes or features that describe the category.

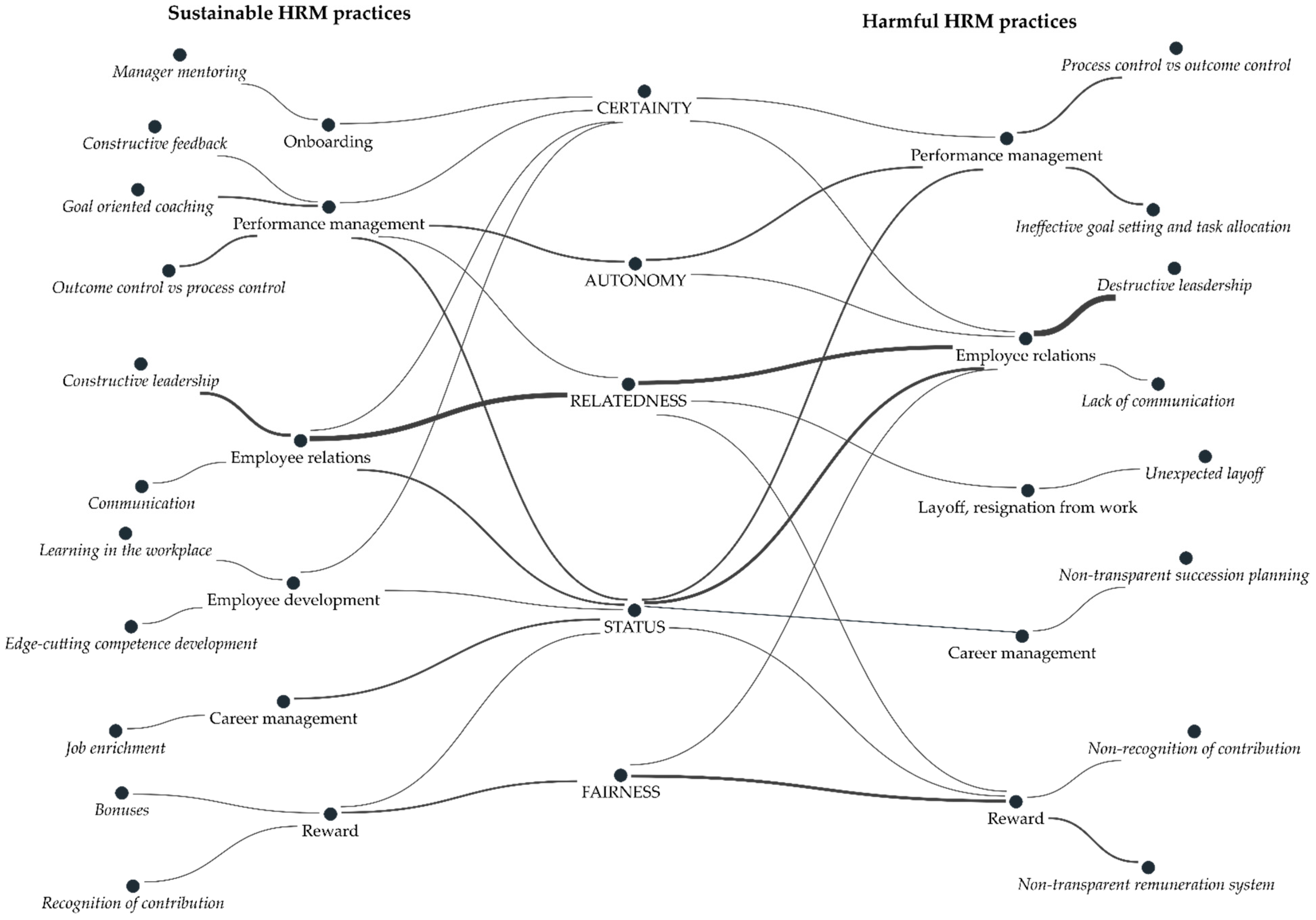

4. Results

4.1. Employees’ Perception of SCARF

Autonomy is working under individual conditions, mainly working individually, where each person has divided the tasks that they perform into their positions and finally everything is combined into one. However, to work autonomously means to work separately.(R34, Pos. 32)

4.2. HRM Practices in Shaping the Psychosocial Experience of Employees

4.2.1. The Role of Sustainable HRM Practices in Shaping Positive Psychosocial Experience of Employees

The feeling of status was probably strengthened when they offered me a high position, which I thought I was not worthy. I did not have that much experience, but they trusted me. It was probably recognition, trust, and empowerment, and at that time, I felt excellent.(R21, Pos. 6)

We had a lot of difficulty installing new machines. <…> I myself had a lot of stress because the production process changed. I had to learn new things, but I learned them quickly. I received praise from my manager, whereas now I advise others <…>. They raised my salary and I think I have such a good status as an employee.(R5, Pos. 18)

I got a complex task and he [the manager] didn’t tell me what, when and how I had to do it. He just told me what the expected result was and what I should get. Everything else I could decide for myself.(R10, Pos. 9)

He [the manager] trusted me when he let me do certain tasks according to my capabilities <…>, and then I did it myself, as I thought [was the right way], and then at the end he pointed the mistakes to me. Then I corrected them. That really boosts self-confidence; you feel professional.(R29, Pos. 19)

He [the manager] commented on everything that he thought needed to be changed, what needed to be done differently, and made his arguments clear. <…> I felt like an equal partner when the manager gave advice, because, of course, he had more experience, but he also listened to you. And then you understand what and why you need to change.(R38, Pos. 38)

At first, I was afraid that I would have to perform a task when I did not know exactly what was being asked of me. However, at every step, the manager simply asked if I understood what I was doing, if I knew what I was doing, if I understood, and explained what was expected of me. Although we were critically pressured to do [the work] as quickly as possible, the manager was always there to ask. At that moment I felt good that even though the boat was sinking, even in a critical situation, the manager still found time to ask how things were going, to advise, to explain.(R9, Pos. 20)

There is a reward system that is public, transparent and everyone can see what they must do and how they will be evaluated for it. When there is such a clear [reward] system, then justice is strengthened.(R26, Pos. 28)

The first thing was that she [the manager], was confident in herself and through this confidence she placed trust in her team. So [it was very important], this moment, when she radiated confidence, kept her word—she always kept our agreements, she never showed that she was the manager and you were the subordinate, it was the communication of equals. Moreover, the communication covered not only work. During the meetings, we used to talk both about work and general things in life.(R1, Pos. 22)

Communication is needed <…> on all matters, be they financial or pertaining to a striving for a vision or about the results. Communication must be sincere <…> when it [communication] is sincere and open, it mobilizes the people for a common goal.(R3, Pos. 20)

Team building, let us say, when drinking coffee together <…> over the last few years this tradition has grown on all of us. Everyone has common subjects to talk about with others, [they can] ask how do you do <…>. It is a very good thing, that building of internal environment from small things, encouraging to meet for coffee in the kitchenette, <…> it used to be, like, for example, with simple documents, when you come to inquire, but it seems as if you are asking for a favor. Now, to the contrary, everybody knows that we are here for each other, but together we are as one.(R16, Pos. 25)

4.2.2. The Role of Harmful HRM Practices in Shaping Negative Psychosocial Experience of Employees

They hold interviews after the probation period and everything is done as appropriate, but you realize that the interviews are just a formality. They just copy the same things over and over again—so you are happy, very happy, so all is good and fine. <…> However, they are not interested in listening, showing genuine interest and maintaining a relationship.(R48, Pos. 28)

The director just decided, and after 3 months he made me a manager, without even asking me. In that sense, this was so surprising to me, such an attitude towards the employee, that he just told me to lead the team.(R44, Pos. 23)

They appointed me to a high position, but I was nonetheless suggested what to do and how to do it. <…> It’s a bit annoying, that lack of autonomy and constant instructions or advice, concern about what and how to do, because it undermines my sense of status, because I myself know what needs to be done.(R10, Pos. 6)

Maybe it just hurts…, but I put in a lot of work, and somehow I expected to be appreciated and maybe promoted to a higher position. However, I was not appreciated, the contract was not extended. I put in a lot of work, and somehow I was left feeling like a half-broken shell.(R37, Pos. 7)

They didn’t notify me in advance [about the dismissal]. It was done in a single day. If they at least came and told me. No. They put a sheet [in writing]. I thought the manager lacked the competence to fire the employees, but I was neither the first nor the last, it turned out. I haven’t forgiven him yet. It’s just that the form could have been different.(R11, Pos. 22)

I think I was a little unfairly evaluated for the set-up of the new equipment. I coordinated everything with XXX suppliers, and my bonus was ridiculously small. We worked a lot of overtime because we stayed up all night. Of course, they paid for it, but the bonus was nonetheless symbolic.(R5, Pos. 56)

Instead of saying just one word, ’Wow, you did a great job’, one word would have been enough, or ’You did a good job’, he said: ’You could have done more’. Well, in that sense, it’s impossible to do more, so he understands that himself, but somehow he behaves in the opposite way.(R6, Pos. 46)

I had to fill in the time tables at work, what I did and how long it took <…>. I didn’t like that kind of control. It was exhausting for me, because you always have to think about what you did there and you have to allocate time [for that]. <…> That’s what weakened the sense of autonomy.(R37, Pos. 27)

The manager gave me a task that was new to me, and it took me a long time to read how to perform the task correctly and not to make any mistakes. The manager simply did not have the patience, did not give me time to prepare, and simply passed the task on to someone else without saying anything. In that situation, I felt humiliated because he [the manager] looked at me as inferior and said that I could not perform certain tasks. He did not even give me a chance, as I had not even started on this task.(R9, Pos. 6)

Poor communication weakens relatedness because miscommunication occurs. Then one or the other starts getting nervous because they don’t communicate—one just talks about the table, the other—about the chair, and that’s it.(R3, Pos. 34)

It weakened both your sense of status and certainty when you were criticized in public in front of everyone. This public scolding is demeaning, and not only because it humiliates you in the eyes of other colleagues, but you also start to distrust yourself and feel uncertainty.(R10, Pos. 12)

4.3. An Outline of the Research Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCARF | Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness, and Fairness |

| HPWS | High-Performance Work Practices |

| HRM | Human Resource Management |

| R | Participant |

References

- Piwowar-Sulej, K. Human resources development as an element of sustainable HRM–with the focus on production engineers. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 124008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guest, D.E. Human resource management and employee well-being: Towards a new analytic framework. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2017, 27, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, G.H. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st-Century Business; Capstone Press: North Mankato, MN, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, G.K.; Brewster, C.J.; Collings, D.G.; Hajro, A. Enhancing the role of human resource management in corporate sustainability and social responsibility: A multi-stakeholder, multidimensional approach to HRM. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankevičiūtė, Ž.; Savanevičienė, A. Designing sustainable HRM: The core characteristics of emerging field. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, I.; Harry, W.; Zink, K.J. Sustainability and HRM. An introduction to the field. In Sustainability and Human Resource Management: Developing Sustainable Business Organizations; Ehnert, I., Harry, W., Zink, K.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Qamar, F.; Afshan, G.; Rana, S.A. Sustainable HRM and well-being: Systematic review and future research agenda. Manag. Rev. Q. 2023, 74, 2289–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, D. SCARF: A brain-based model for collaborating with and influencing others. NeuroLeadership J. 2008, 1, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Rock, D.; Cox, C. SCARF in 2012: Updating the social neuroscience of collaborating with others. NeuroLeadership J. 2012, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Stankevičiūtė, Ž.; Savanevičienė, A.; Girdauskienė, L. Linkage between Workplace Environment and Socio-psychological Experience of Employees: A Literature Review. Int. J. Interdiscip. Organ. Stud. 2024, 19, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.M.; Hansen, J.W.; Madsen, S.R. Improving how we lead and manage in business marketing during and after a market crisis: The importance of perceived status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness and fairness. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2022, 37, 1974–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, P.; Mardani, A.; Mishra, A.R.; Cajas, V.E.C.; Carvajal, M.G. Evaluate sustainable human resource management in the manufacturing companies using an extended Pythagorean fuzzy SWARA-TOPSIS method. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 370, 133380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-García, I.; Alonso-Muñoz, S.; González-Sánchez, R.; Medina-Salgado, M.S. Human resource management and sustainability: Bridging the 2030 agenda. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 2033–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, T.S.C.; Law, K.K. Sustainable HRM: An extension of the paradox perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2022, 32, 100818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, G.P.; Coelho, A.; Ribeiro, N. A systematic literature review on sustainable HRM and its relations with employees’ attitudes: State of art and future research agenda. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2025, 12, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakra, N.; Kashyap, V. Responsible leadership and organizational sustainability performance: Investigating the mediating role of sustainable HRM. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2025, 74, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labelle, F.; Parent-Lamarche, A.; Koropogui, S.T.; Chouchane, R. The relationship between sustainable HRM practices and employees’ attraction: The influence of SME managers’ values and intentions. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2025, 12, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Cooke, F.L.; Stahl, G.K.; Fan, D.; Timming, A.R. Advancing the sustainability agenda through strategic human resource management: Insights and suggestions for future research. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 62, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aust, I.; Matthews, B.; Muller-Camen, M. Common good HRM: A paradigm shift in sustainable HRM? Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 30, 100705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniškienė, E.; Stankevičiūtė, Ž.; Daunorienė, A.; Ramanauskaitė, J. Theoretical Insights on Organisational Transitions Towards CSR. In Transformation of Business Organization Towards Sustainability; World Sustainability Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramar, R. Beyond strategic human resource management: Is sustainable human resource management the next approach? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järlström, M.; Saru, E.; Pekkarinen, A. Practices of sustainable human resource management in three Finnish companies: Comparative case study. South Asian J. Bus. Manag. Cases 2023, 12, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aust, I.; Cooke, F.L.; Muller-Camen, M.; Wood, G. Achieving sustainable development goals through common-good HRM: Context, approach and practice. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 38, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, S.; Kaur, K.; Patel, P.; Kumar, S.; Prikshat, V. Integrating sustainable development goals into HRM in emerging markets: An empirical investigation of Indian and Chinese banks. Int. J. Manpow. 2025, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Tang, G.; Jackson, S.E. Effects of Green HRM and CEO ethical leadership on organizations’ environmental performance. Int. J. Manpow. 2021, 42, 961–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, I. Paradox as a lens for theorizing sustainable HRM: Mapping and coping with paradoxes and tensions. In Sustainability and Human Resource Management: Developing Sustainable Business Organizations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 247–271. [Google Scholar]

- Mariappanadar, S. High Performance Sustainable Work Practices: Scale Development and Validation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappanadar, S. Stakeholder harm index: A framework to review work intensification from the critical HRM perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2014, 24, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappanadar, S.; Kramar, R. Sustainable HRM: The synthesis effect of high performance work systems on organisational performance and employee harm. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2014, 6, 206–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaugg, R.J. Sustainable HR Management: New Perspectives and Empirical Explanations; Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2009; ISBN 978-3-8349-2103-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ehnert, I. Sustainability and HRM: A model and suggestions for future research. In The Future of Employment Relations. New Paradigms, New Developments; Wilkinson, A., Townsend, K., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2011; pp. 215–237. ISBN 978-0-230-24094-0. [Google Scholar]

- Guerci, M.; Pedrini, M. The consensus between Italian HR and sustainability managers on HR management for sustainability-driven change–towards a ‘strong’HR management system. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1787–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esen, D.; Özer, P.S. Sustainable Human Resources Management (Hrm) a study in Turkey context and developing a sustainable HRM questionnaire. Int. J. Manag. Econ. Bus. 2020, 16, 550–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumpff, C.; Monzel, A.S.; Sandi, C.; Menon, V.; Klein, H.U.; Fujita, M.; Lee, A.; Petyuk, V.A.; Hurst, C.; Duong, D.M.; et al. Psychosocial experiences are associated with human brain mitochondrial biology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2317673121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramble, M.; Campbell, S.J.; Walsh, K.; Prior, S.; Doherty, D.; Bramble, M.; Marlow, A.; Maxwell, H. Examining the engagement of health services staff in change management: Modifying the SCARF assessment model. Int. Pract. Dev. J. 2022, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiguchi, T.; Li, J.; Hosomi, M. Predicting job crafting from the socially embedded perspective: The interactive effect of job autonomy, social skill, and employee status. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2017, 53, 470–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yin, X.; Li, S.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, F. The Relationship Between Employee’s Status Perception and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: A Psychological Path of Work Vitality. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021, 14, 743–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, L.; An, Z.; Lu, L.; Yao, S. Job-related burnout is associated with brain neurotransmitter levels in Chinese medical workers: A cross-sectional study. J. Int. Med. Res. 2018, 46, 3226–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aplin-Houtz, M.; Munoz, L.; Fergurson, J.R.; Fleming, D.E.; Miller, R.J. What matters to students? a scarf-based model of educational service recovery. Mark. Educ. Rev. 2023, 33, 320–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadizadeh, B.; Aplin-Houtz, M.; Casile, M. Using SCARF as a motivational tool to enhance students′ class performance. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, D. Your Brain at Work: Strategies for Overcoming Distraction, Regaining Focus, and Working Smarter All Day Long; HarperCollins e-books: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Park, R. What if employees with intrinsic work values are given autonomy in worker co-operatives? Integration of the job demands–resources model and supplies–values fit theory. Pers. Rev. 2023, 52, 724–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahy, M.; Dowling-Hetherington, L.; Phillips, D.; Moloney, B.; Duffy, C.; Paul, G.; Fealy, G.; Kroll, T.; Lafferty, A. If my boss wasn’t so accommodating, I don’t know what I would do’: Workplace supports for carers and the role of line managers and co-workers in mediating informal flexibility. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2025, 35, 302–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Roesler, U.; Kusserow, T.; Rau, R. Uncertainty in the workplace: Examining role ambiguity and role conflict, and their link to depression—A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Work. Org. Psychol. 2014, 23, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolemba, M. Brain as a social organ. Practical application of social awards and threats-SCARF model-in management and building customer relationships training. Gen. Prof. Educ. 2016, 2, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Manjaly, N.B.; India, F.C.; India, M.; Francis, D.; Francis, V.; India, R. Leveraging the SCARF Model For Employee Engagement: An In-Depth Analysis With Special Reference To Government Organisations. J. Econ. Financ. Manag. Stud. 2024, 7, 3412–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, D. Interpreting Qualitative Data. Methods for Analyzing Talk, Text and Interaction; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Agbenyega, J.S.; Tamakloe, D. Using Collaborative Instructional Approaches to Prepare Competent Inclusive Education Student Teachers. In Instructional Collaboration in International Inclusive Education Contexts (International Perspectives on Inclusive Education); Semon, S.R., Lane, D., Jones, P., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2021; Volume 17, pp. 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Ma, Q.; Hu, H.; Zhou, K.H.; Wei, S. A study of the spatial network structure of ethnic regions in Northwest China based on multiple factor flows in the context of COVID-19: Evidence from Ningxia. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions a STEM Education Strategic Plan: Skills for Competitiveness and Innovation. Brussels, 5.3.2025 COM(2025) 89 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?Uri=CELEX%3A52025DC0089 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Aslam, S.; Saleem, A.; Kennedy, T.J.; Kumar, T.; Parveen, K.; Akram, H.; Zhang, B. Identifying the Research and Trends in STEM Education in Pakistan: A Systematic Literature Review. SAGE Open 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldana, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pletzer, J.L.; Breevaart, K.; Bakker, A.B. Constructive and destructive leadership in job demands-resources theory: A meta-analytic test of the motivational and health-impairment pathways. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 14, 131–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, K. A reward-learning framework of knowledge acquisition: An integrated account of curiosity, interest, and intrinsic–extrinsic rewards. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 129, 175–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, F.; Zhou, H.; Hu, H. Nip it in the bud: The impact of China’s large-scale free physical examination program on health care expenditures for elderly people. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, T.; Höft, L.J.; Bahr, L.; Kuklick, L.; Meyer, J. Constructive feedback can function as a reward: Students’ emotional profiles in reaction to feedback perception mediate associations with task interest. Learn. Instr. 2025, 95, 102030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robroek, S.J.W.; Coenen, P.; Oude Hengel, K.M. Decades of workplace health promotion research: Marginal gains or a bright future ahead. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2021, 47, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, G.S.; Vilaça, T. Editorial: Health promotion in schools, universities, workplaces, and communities. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1528206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Contribution | References | Detailing |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical contribution | [9,10,39,42,46] | SCARF model development |

| [11] | Systematic literature review | |

| Empirical contribution | [12] | B2B sector: linkage between employees’ perception of SCARF and intention to leave an organization (quantitative study) |

| [41] | Educational sector: linkage between students’ perception of SCARF and motivation (quantitative study) | |

| [36] | Healthcare sector: linkage between employees’ perception of SCARF and engagement (quantitative study) | |

| [47] | Public sector: linkage between employees’ perception of SCARF and engagement (quantitative study) |

| SCARF Dimensions | Questions Regarding the Impact of HRM Practices on STEM Workers’ Psychosocial Experiences |

|---|---|

| Status |

|

| Similar questions were asked to reveal the impact of HRM practices on certainty, autonomy, relatedness, and fairness. | |

| Theme | Category | Characteristic, N * |

|---|---|---|

| SCARF | Status | Position associated with responsibility (N = 27) |

| Professionalism (N = 13) Self-realization (N = 4) Financial status (N = 3) | ||

| Certainty | Employability (N = 15) | |

| Certainty that you will cope with tasks (N = 12) Certainty about the future (N = 10) Perception that you are not alone (N = 9) Knowing what results are expected or how to perform a task (N = 7) Financial safety (N = 7) | ||

| Independent decision-making (N = 42) | ||

| Autonomy | Time management (N = 9) | |

| Working individually, separately from others (N = 3) | ||

| Relatedness | Good microclimate (N = 23) | |

| Teamwork, common goal (N = 13) | ||

| Respect (N = 12) | ||

| Close relations with manager, colleagues (N = 11) | ||

| Subordination compliance (N = 4) | ||

| Fairness | Reward based on merit (N = 20) | |

| General rules for all (N = 19) | ||

| Transparency (N = 8) | ||

| Recognition of contribution (N = 7) | ||

| Equality (N = 4) |

| Theme | Category | Characteristic, N * |

|---|---|---|

| Onboarding | Manager mentoring (N = 3) Peer mentoring (N = 2) | |

| Sustainable HRM practices | Career management | Job enrichment (N = 6) Promotion (N = 2) |

| Employee development | Edge-cutting competence development (N = 5) Learning in the workplace (N = 4) Manager’s support during studies (N = 2) | |

| Reward | Recognition (N = 7) Bonuses (N = 4) | |

| Performance management | Goal-oriented coaching (N = 12) | |

| Outcome control vs. process control (N = 7) Constructive feedback (N = 5) | ||

| Employee relations | Authentic leadership (N = 15) Communication (N = 14) Informal events (N = 4) |

| Theme | Category | Characteristic, N * |

|---|---|---|

| Onboarding (N = 3) | Formal approach to onboarding (N = 3) | |

| Harmful HRM practices | Career management (N = 7) | Non-transparent succession planning (N = 4) Promotion issues (N = 3) |

| Layoff, resignation from work (N = 6) | Unexpected layoff (N = 4) Disrespectful behavior of the manager (N = 2) | |

| Employee development (N = 4) | Refusal to support the employee’s initiative to study (N = 3) Lack of guidelines for competencies development (N = 1) | |

| Reward (N = 16) | Non-transparent remuneration system (N = 8) Non-recognition of contribution (N = 5) Financial reward not matching the merit (N = 3) | |

| Performance management (N = 20) | Process control vs. outcome control (N = 9) Ineffective goal setting and task allocation (N = 8) Unclear performance evaluation criteria (N = 2) Lack of feedback (N = 1) | |

| Employee relations (N = 34) | Regressive leadership (N = 31) Lack of communication (N = 3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Savanevičienė, A.; Girdauskienė, L.; Stankevičiūtė, Ž. The Role of HRM Practices in Shaping a Positive Psychosocial Experience of Employees: Insights from the SCARF Model. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4528. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104528

Savanevičienė A, Girdauskienė L, Stankevičiūtė Ž. The Role of HRM Practices in Shaping a Positive Psychosocial Experience of Employees: Insights from the SCARF Model. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4528. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104528

Chicago/Turabian StyleSavanevičienė, Asta, Lina Girdauskienė, and Živilė Stankevičiūtė. 2025. "The Role of HRM Practices in Shaping a Positive Psychosocial Experience of Employees: Insights from the SCARF Model" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4528. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104528

APA StyleSavanevičienė, A., Girdauskienė, L., & Stankevičiūtė, Ž. (2025). The Role of HRM Practices in Shaping a Positive Psychosocial Experience of Employees: Insights from the SCARF Model. Sustainability, 17(10), 4528. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104528