1. Introduction

1.1. The Purpose of the Work

One of the Sustainable Development Goals is quality education, which aims to ensure inclusive and equitable quality learning and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. During the pandemic, the higher education system underwent radical transformations that required an adaptation to new realities.

The life of modern man has undergone critical transformations in almost all aspects due to the revolutionary development of digital technologies. One of the most significant spheres shaping human life and subjected to transformation during the rapid development of information and communication technologies is the sphere of education. Under the conditions of the accelerated digital transformation of higher education, multiple changes occur not only in the forms of organization of the process of knowledge transfer but also in the content of educational programs, as well as in the process of interaction in the student–teacher system.

It is important to note that the critical acceleration of transformation processes affected almost all social institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic, which provoked their forced digitalization. These processes directly involved the education system [

1]. Almost immediately, the overwhelming number of technical universities in the Russian Federation was forced to switch to a fully distance learning format for quite a long period of time [

2]. This mass transition provoked a radical increase in interest in the already quite controversial topic of distance education. In this paper, this effect is called the catalyzing factor. This effect has already been considered in more detail by the author’s team in [

3]. Such interest has generated a lot of sociological studies of students aimed at investigating their attitudes toward distance learning. In particular, the vast majority of works considered various advantages and disadvantages and sought to identify the most significant ones for the student community.

However, as time passed, the effect of the suddenness passed and universities returned to the face-to-face format of learning. Now, conducting studies is of great interest to the research community in terms of determining how the attitudes of learners change long after they have left the distance format. Each of the interviewees had personally experienced distance learning, was able to evaluate all of its advantages and disadvantages on their own, and then returned to face-to-face learning and obtained a kind of comparative picture of all aspects of learning. Would the learner rate the advantages or disadvantages of distance education so highly after such a comparison opportunity?

Thus, the purpose of this paper is to analyze the change in learners’ attitudes toward the distance learning format over time in the absence of the catalyzing effect of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This perspective is fully aligned with the international policy agenda on sustainable development. The United Nations, through the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [

4], emphasizes the importance of inclusive and equitable quality education (SDG 4) as a foundation for building resilient societies. Similarly, UNESCO highlights the need for flexible, future-oriented learning systems that prepare individuals to adapt and thrive in rapidly changing contexts [

5,

6]. These principles reinforce the relevance of studying the long-term dynamics of distance education in higher education settings.

1.2. Literature Review

The topic of distance education has been discussed since the mass digitalization of educational institutions [

7,

8], covering topics ranging from the explosive impact of distance learning on all aspects of social life [

3] to understanding the digital divide that limits opportunities for quality education [

8]. At the initial stage of the discussion of this topic, different aspects were highlighted [

9,

10], including the possibilities to reduce the time costs of the learning process, which can be traced in a number of sources [

11,

12]. This time reduction is assumed to be due to movement around a city [

13]. An interesting factor among the advantages is to highlight the reduction of transportation movements [

14] and the positive impact on the environmental situation [

15,

16]. Among the early advantages of distance education, the potential for access to learning for people with disabilities was particularly emphasized [

17].

The forced digitalization of the COVID-19 era is becoming a catalyzing effect for the spread of online learning globally [

3]. The forced widespread transition to distance education initially exacerbated various problems [

18], requiring teachers to incur enormous costs in terms of their time to prepare for classes, to adapt existing teaching materials to the new teaching format [

19], and emotional restructuring [

20]. Gradually, these factors were leveled [

21], but other factors suddenly became dominant.

Among them, a loss of interest [

22] and the quality of distance education [

23] stand out. Important factors during the pandemic were the problems of motivation [

24] and self-motivation [

25] and the lack of material resources in some segments of the population [

26], especially in developing countries [

27]. Studies have also noted that students and their parents felt overwhelmed by excessive messages in various educational and educational chat rooms [

28].

In the framework of this study, the results of similar sociological studies are of particular interest. Therefore, a literature review of sociological surveys and the conclusions of these sources was conducted regarding the identification of the advantages and disadvantages of distance learning.

When selecting the literature, we relied on the criteria of relevance and therefore considered studies published after 2019, which allowed us to take into account modern changes in distance learning; the authority preference was given to articles from peer-reviewed international journals with a high impact factor, as well as a practical component, that is, articles containing empirical data. To form the conceptual basis of this study, sources were provided covering key aspects of distance education in the field of engineering disciplines. Particular attention was paid to publications analyzing the impacts of digital technologies on the quality educational process, academic motivation of students, and the effectiveness of online teaching methods. This approach provides a comprehensive analysis of scientific research and allows us to correlate the results with modern developments in this field.

As part of our research work, a key source is the review of the analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of online and offline learning formats in the context of peer learning in higher education [

29]. The relationship between the responses of engineering students and their instructors regarding online courses is traced in this study [

30].

During the peak of the pandemic, when distance learning was implemented in an emergency mode, a study was conducted analyzing distance learning in engineering education, highlighting that remote learning contributed to increased accessibility to education due to the flexibility of formats [

31].

Similarly, those who studied individually with a mentor preferred learning through online platforms [

32], as well as those who attended courses on calculus and numerical methods [

33].

In engineering education, the transition to a digital format has revealed, in particular, challenges related [

34] to laboratories and practical work [

35]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, remote laboratories became an important support tool [

36] but also a challenge at the same time, as they were not accessible to many engineering universities [

37].

At the same time, due to the forced nature of distance learning, the majority of students would have preferred a hybrid format (54%) [

38]. Here, the necessity of effectively preparing all activities in online courses played a crucial role [

39]. Modern researchers emphasize the potential of e-learning as a long-term educational tool, highlighting its convenience, flexibility, and opportunities for interaction [

40].

Some studies were very close to ours in terms of the format of questions and answers, and so it was logical to consolidate them into a unified form, showcasing the advantages and disadvantages identified by students. The material from these articles will be presented in the form of a table (

Table 1). To summarize the sociological studies, three groups of advantages and five groups of disadvantages were identified.

Advantages:

A1. Time-saving

A2. Qualitative improvement of the education process

A3. Individualization of the education process

Disadvantages:

D1. Social factor

D2. Motivation problem

D3. Technical difficulties

D4. Specificity of the specialty

D5. Difficulties in mastering the material

The left column contains all the main information about the research methodology. Each cell in the right column will be divided into two parts. The first part will also contain eight columns, reflecting whether the corresponding group of advantages or disadvantages was considered in the study and what hierarchical position it received based on the results of the research. For example, if in advantage A1 there is a “one”, in advantage A2 there is a “two”, and in advantage A3 it says “No,” this means that the study considered only the groups of advantages “A1. Time-saving” and “A2. Qualitative improvement of the education process.” The analysis results showed that respondents rated A1 higher than A2. The second part of the cell will present brief conclusions from the reviewed study.

Separately, it should be noted the works that cannot be compared directly, as they investigate separate aspects of distance learning. Thus, in [

48], the advantages and disadvantages of using LMS Moodle are considered, both from the points of view of students and teachers. A very detailed study of the advantages and disadvantages of online lectures is presented in [

49]. The issue of learning foreign languages and Russian as a foreign language in a distance format stands out [

50,

51]. The issue of behavioral health risks during distance education is devoted to the work [

52]. The topic of introducing distance education in regional universities deserves a separate influence [

53]. The advantages and disadvantages of distance education from the point of view of students by other methods are evaluated in the works [

54,

55,

56]. If we talk about the methods of distance education, the experience of introducing distance education is presented in great detail in works [

57,

58,

59].

2. Materials and Methods

The first stage of our research was the analysis of scientific articles and sociological studies on the topic “Advantages and disadvantages of distance education”. For the works used in the compilation of the summary table, the main parameter was the use of methods of surveying students on the topic “Advantages and disadvantages of distance education”, as well as the presence of a clear justified list of options and the relevance of the study. The selection of sources followed a systematic approach, as detailed in the

Section 1.2 above. This purposive selection allows us to align our analysis with current research while simultaneously contributing new insights into engineering students’ experiences of distance learning.

As part of this study, a survey was conducted among students of engineering specialties in different courses from several universities in St. Petersburg. Respondent selection was based on pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure a representative sample that meets the objectives of the study. The inclusion criteria were studying at an engineering university, experience of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, and voluntary participation. The exclusion criteria included students who completed their studies before the second wave of the survey, those with no previous experience of distance learning, and responses with incomplete data. This approach ensured the comparability of respondents between the two survey waves and minimized potential bias.

The main reason for this choice is the specifics of engineering education, which makes the distance learning format particularly difficult and, at the same time, a unique object for analysis. Engineering specialties involve not only the theoretical study of subjects but also a significant proportion of practical exercises, laboratory work, and design activities. In the context of distance learning, access to these types of activities was limited or required serious adaptation. This created a unique situation in which engineering students could experience more pronounced difficulties compared to students in the humanities or economics, where the educational process is more focused on lecture and seminar forms of work.

Based on the obtained data presented in

Table 1, the sample of response options was adjusted in such a way that it became possible to compare the planned results of the study with the literature data. The sample was also formed based on the following research objectives: (1) to identify the attitudes of engineering students in different courses toward distance education during the most active influence of the catalyzing factor of the pandemic; (2) to identify the attitudes of engineering students in different courses toward distance education during the period of the reduced influence of the catalyzing factor of the pandemic; and (3) to explicate the changes in the assessment of engineering students’ evaluations of the advantages and disadvantages of distance education. It was decided to conduct a longitudinal study.

Thus, the survey was conducted in two stages. The first stage was conducted immediately after the students left the distance learning format in the 2021/2022 academic year. The second stage was conducted 2 years later in the 2023/2024 academic year. The number of respondents in the first phase was 653. In the second stage, 194 learners were surveyed. All those who took part in both stages were students of engineering specialties in different courses from the universities of St. Petersburg. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the protocol of the expert committee for control and examination of the Saint Petersburg Mining University. The survey was fully anonymous, participation was voluntary, and no personal or sensitive data were collected.

This reduction in sample size was expected given the two-year gap between surveys. By the time of follow-up, many of the original respondents had completed their studies. However, the second wave respondents still represented a mix of engineering students from different years, allowing us to continue longitudinal comparisons, despite the smaller sample.

Participation in the survey was completely voluntary and anonymous. Anonymity was ensured by disabling the parameter responsible for collecting e-mail addresses in the form settings.

Details of the full results of the survey can be found at the link provided in the proceedings of this paper.

The survey was distributed to the students of engineering specialties of different courses through the use of social media. The survey consisted of 14 questions, and the same list of questions and answer choices were used at each stage. However, this study considered only a block of questions directly related to the problematic of the publication and corresponding to the stated goal and objectives of this study.

The questionnaire was designed in such a way as to divide the respondents into three major categories:

1st–2nd year students, i.e., students who have just started the process of higher education and have not yet fully adapted to the learning environment;

3rd–5th year students, i.e., students in their senior years of university education who have already successfully adapted to the conditions of higher education institution;

Master’s students, i.e., students who have already successfully adapted to the conditions of a higher education institution and who are learning the skills of independent scientific work.

After a representative number of participants had been recruited and the main flow of those willing to participate in the study was over, access to the survey was closed.

The results were then uploaded in an xls file format. Then with the help of a program in the Python 3.8 language developed by the authors’ team, the processing of the source material was carried out. The program generates reports in xls file format and supports the following report blocks. The collected data were analyzed using statistical methods in Python scripts developed for the research methodology. Descriptive statistics, including frequency distributions and means, were calculated for all main surveys. A correlation analysis was performed to analyze the relationships between key factors, such as motivation, technical difficulties, and perceptions of learning quality. This multi-component analytical approach allowed for a comprehensive assessment of trends and differences over time.

Given the longitudinal nature of the study, with data collected at two time points (2021 and 2023), we were able to analyze changes in students’ attitudes over time. A comparative analysis was conducted using frequency-based statistics and descriptive group comparisons to identify evolving trends. This longitudinal approach allowed us to assess how the perceptions of different cohorts shifted as they progressed through their academic journey.

The simplest variant is the output of the number of respondents and the percentage of answers for each option for each question. The questions are in an order similar to the form. In this block of the report, only responses with one possible survey option are analyzed. The block is called General Statistics.

In the second mode of interaction, a separate sheet is automatically created for each question in the Excel spreadsheet, where the results are divided into separate columns depending on which answer option the respondents chose for this question. Thus, this group allows you to evaluate how people who chose a certain answer option for a given question responded to other questions. In this block of the report, only responses with one possible survey option are analyzed. The block is named “Detailed Statistics”.

The last block was designed specifically for analyzing multiple responses. It supports the functions of the General Statistics block, but for multiple choice questions. In addition, you can specify a single answer question, in which case a number of Excel sheets will be created equal to the number of answer choices in that question, and then the sheets will display statistics for all multiple choice questions among respondents who selected that answer choice in the single answer question. The block is named “Multiple Answers”.

Thus, the developed program allows us to quickly present the distribution of respondents into categories in a form that is convenient for understanding and further analysis.

In order to reveal the attitudes of engineering students in different courses to distance learning, two questions were formed, including the advantages and disadvantages of distance learning most frequently used in the scientific literature.

Among the advantages, the following options were available for selection:

No need to spend time traveling to the place of study;

Opportunity to study not only in the university premises;

Use of modern computer and mobile devices.

Flexibility in scheduling training;

Formation of independence and self-organization in learning;

Distance learning facilitates individual communication with the teacher;

Speed of communication.

Among the disadvantages, the following options were available for selection:

Lack of real communication;

The need for strict, constant self-discipline;

Technical difficulties (difficulties with connection problems with sound and image, sometimes difficulties with Internet access).

Lack of control as a consequence of irregular fulfillment of tasks and more time to complete tasks;

Lack of real communication with other students, classmates;

Not all specialties can be studied remotely;

Distance learning is mainly in written form, which hinders the development of communication and speech skills.

A comparative analysis was performed using standardized categories from prior studies (

Table 1).

The survey items were matched to the categories identified through the literature review. To achieve this, the method of a factor analysis was used (

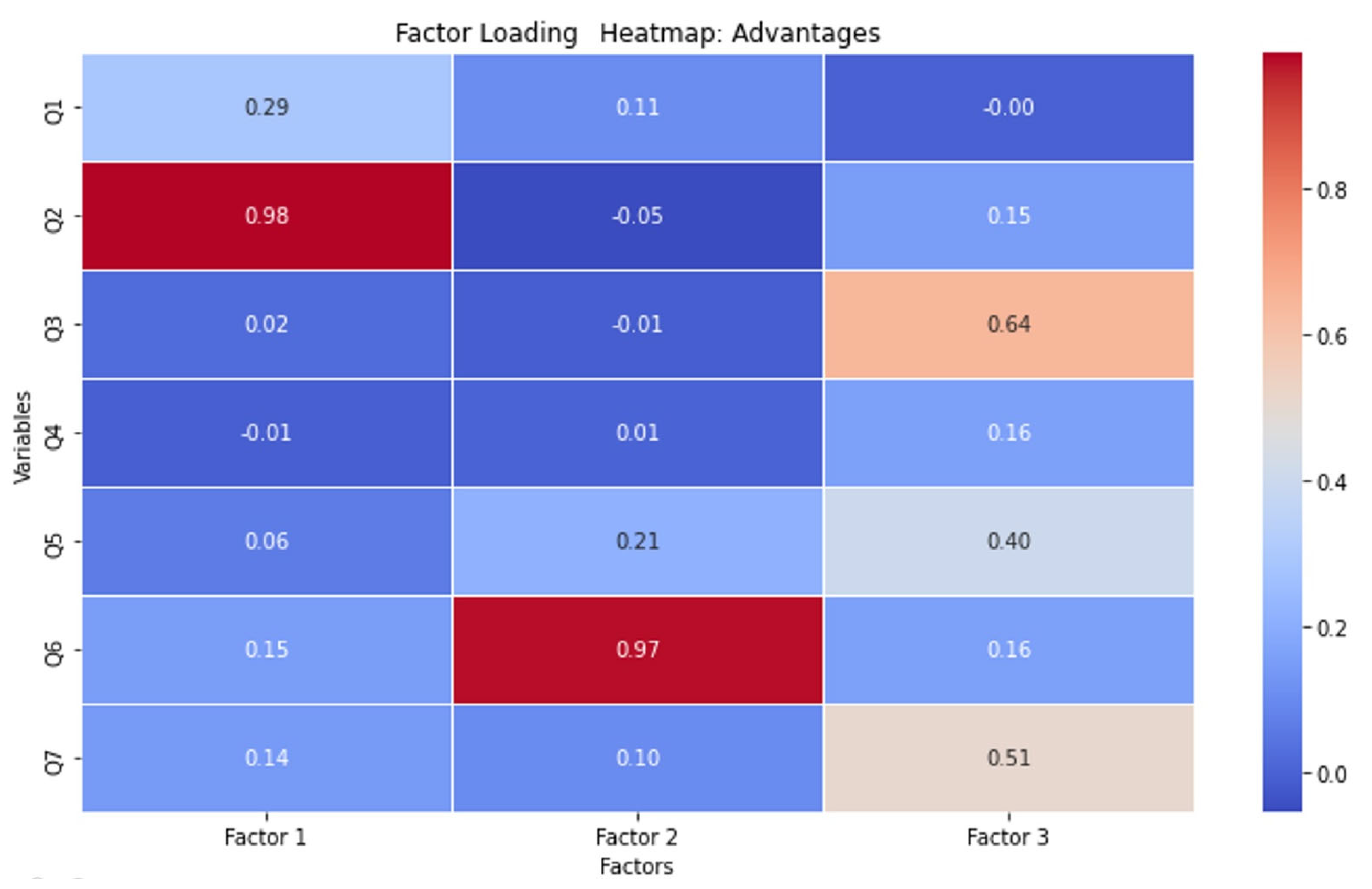

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

Qualitative improvement of the education process—Factor 1 (Flexibility in planning training—Q1 and Formation of independence and self-organization in learning—Q2);

Individualization of the education process—Factor 2 (Opportunity to study not only in the university premises—Q6);

Time saving—Factor 3 (No need to spend time traveling to the place of study—Q4, Distance learning facilitates individual communication with the teacher—Q7, Speed of communication—Q3, and Use of modern computer and mobile devices—Q5).

Five categories were formulated for the disadvantages:

Social factor—Factor 1 (Lack of real communication—Q9, Lack of real communication with other students classmates—Q10, and Distance learning is mainly in written form, which hinders the development of communication and speech skills—Q14);

Motivation problem—Factor 2 (Need for strict, constant self-discipline—Q12 and Lack of control as a consequence of irregular fulfillment of tasks and more time to complete tasks—Q11);

Specificity of specialty—Factor 3 (Not all specialties can be studied remotely—Q13);

Technical difficulties—Factor 4 (Technical difficulties (difficulties with connection problems with sound and image, sometimes difficulties with Internet access)—Q8);

Difficulties in mastering the material—Factor 5 (no items of this category were presented in the survey).

Each source considered in

Table 1 was analyzed according to the following algorithm. In the Excel spreadsheet, all response options for advantages and disadvantages are written out. The percentage of respondents who chose this option is written out against the answer, and then this number is converted to a fraction by dividing by one hundred. All options are arranged in hierarchical order. The hierarchical number is entered in a separate column. Then, the distribution of the questionnaire items into the previously mentioned categories is made. After that, Formula (1) is used to calculate the weighted average number for each category in the study under consideration (the nomenclature is presented in

Appendix A).

The category with the lowest weighted average is hierarchically superior.

3. Results

3.1. Advantages

The distribution of answers to the question about the advantages of distance learning should first be presented in the form of a general distribution of answers of the respondents in the first stage. This approach allows us to compare the results of this study and the results of the works presented in

Table 1 in the time period, which is characterized by the presence of a high catalyzing factor due to the pandemic period.

Figure 3 shows the statistics of respondents’ answers to the question about the advantages of distance education in the active period of the pandemic. Based on this diagram, the advantages can be presented in the following sequence: no need to spend time on travel to study, flexibility in planning training, possibility to study not in the premises of the university, formation of independence and self-organization in studies, use of modern computers and mobile devices, speed of communication, and facilitation of communication with the teacher (

Figure 3).

If we consider the advantages of distance education in relation to different courses of learners (

Figure 4), it can be noted that the order of this sequence does not depend on the course of study; however, due to the specifics of each group of respondents, the results of individual items can vary in a fairly wide percentage range.

Analyzing the results presented in

Figure 4, it should be noted that such advantages as “No need to spend time on travel to the place of study”, “Distance learning facilitates individual communication with the teacher”, and “Speed of communication” have approximately equal indicators in all studied groups. At the same time, advantages such as “Flexibility in planning training” and “Opportunity to study not only in the university premises” were most highly evaluated by Master’s degree students at 76.1% and 64.8%, respectively. At the same time, in the comparison with other groups, Master’s degree studies rated the advantages “Use of modern computer devices” and “Formation of independence and self-organization in studies” lower, these two advantages were rated more highly by senior students.

Two years later, the distribution had slightly changed (

Figure 5). Thus, at approximately the same level among all groups, the advantage “There is no need to spend time on travel to the place of study” remained and “Formation of independence and self-organization in studies” was added. At the same time, after the passage of time, a decrease in the interest of Master’s degree students in advantages such as “Distance learning facilitates individual communication with the teacher” and “Speed of communication” is clearly observed. It should also be noted that for all items except for “No need to spend time on traveling to the place of study”, the highest indicator is for first-year students, which was not noted in the first part of the study (

Figure 4).

The following is a detailed comparison of the results of the survey of respondents in the first and second stages of the study for each course.

Among first–second-year students (

Figure 6), it is noted that there was an increase in all numerical indicators. The most prominent items were “Flexibility in planning training” and “Speed of communication”; they increased by 20.15% and 9.73%, respectively.

At the same time, the opposite picture was observed among senior students (

Figure 7)—a decrease in all indicators. In this case, it was difficult to identify some of the most notable categories, but the decrease ranged from 3% to 9.71%.

There was a diverse picture in the Master’s program (

Figure 8). Thus, increases in the percentages were observed in the categories “There is no need to spend time traveling to the place of study” and “Use of modern computer and mobile devices”; decreases in “Opportunity to study not only in the university premises”, “Distance learning facilitates individual communication with the teacher”, and “Speed of communication”; and small changes in “Flexibility in planning training” and “Formation of independence and self-organization in learning”.

3.2. Disadvantages

The distribution of answers to the question about the disadvantages of distance education should first be presented in the form of the general distribution of answers of the respondents of the first stage. The presentation of this particular diagram as a general one on the issue of disadvantages of distance education allows us to compare the results of this study and the results of the works presented in

Table 1 in the time period, which is characterized by the presence of a high catalyzing factor due to the pandemic period.

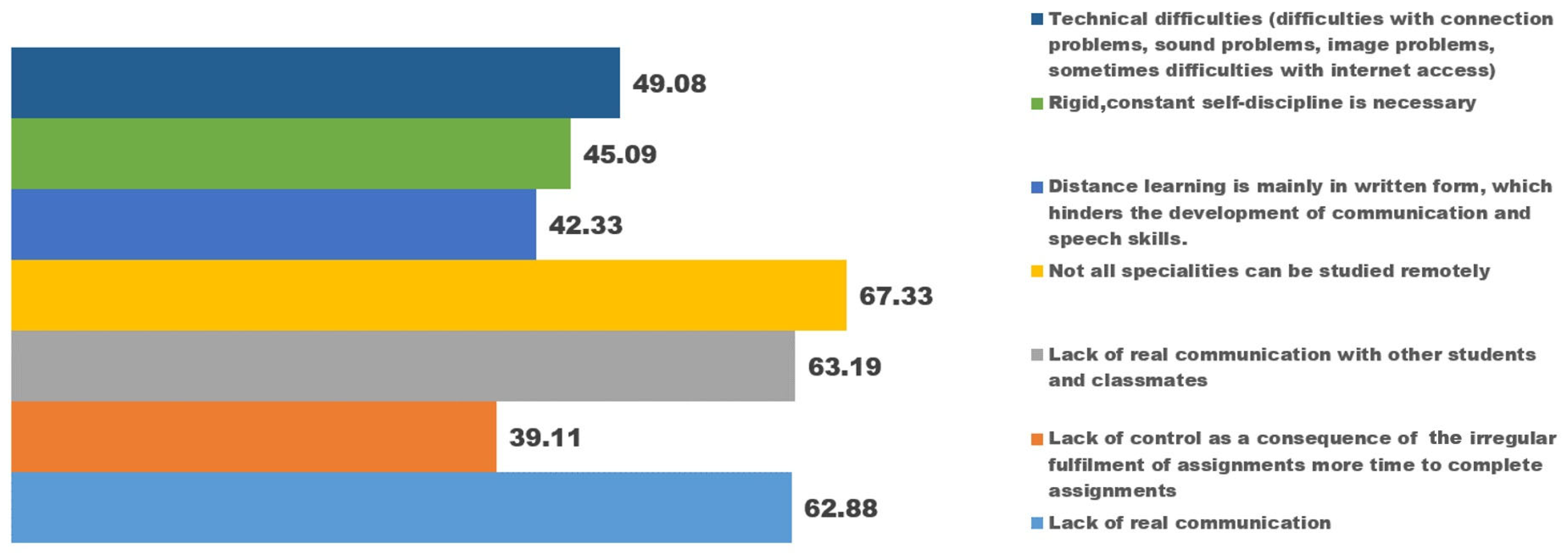

Analyzing the disadvantages of distance learning (

Figure 9), it should be noted that the distribution among them differs more significantly than among the advantages, but general patterns should be highlighted. For this purpose, let us summarize everything in one table (

Table 2).

Analyzing the presented distribution, it can be noted that at both stages of the study, senior students and Master’s degree students chose “Not all specialties can be studied at a distance” as the most significant disadvantage of distance education. However, even among first-year students this item was always in the top three. As the second item at the first stage of the study, “Lack of real communication” was chosen, at the same time, at the second stage, it only took such a high position among Master’s degree students. Also, in all cases, except for the initial courses of the 2023/2024 academic year in the first three points, the disadvantage “Lack of real communication with other students classmates” was noted in both periods.

It is worth noting the disadvantage “Need for strict, constant self-discipline”, which, in the first period of the survey, occupied the lowest positions, but in the second period, it has already reached the first three: fifth, fifth, and seventh and first, second, and fourth places, respectively.

In the first period of the survey, “Technical difficulties (difficulties with connection problems with sound and image, sometimes difficulties with Internet access)” occupied a stable fourth place among all courses, while in the second period, we see a downward trend: fifth, sixth, and seventh places.

The item that never rose above the fifth place was “Distance learning is mainly in written form, which hinders the development of communication and speech skills” and can be considered the least significant.

When considering each group separately, a characteristic tendency observed from the first year to the master’s program on the issues of motivation and self-discipline needs to be noted (

Figure 10). In particular, first-year students attach more importance to this factor; however, the statistical indicators decrease closer to the study in senior courses and in the Master’s program. Thus, in the first-year students, the indicator is 51.1%; in the senior students, it is already 42.9%; and in the Master’s degree students, it is 28.4%. A similar trend is observed when assessing the significance of technical difficulties.

It should also be noted that, as in the case of merits, in all cases except for the item “Not all specialties can be studied remotely”, the highest percentage belongs to junior students. At the same time, the second place is always occupied by senior students, and the last place is occupied by Master’s degree students.

At the second stage of the study, it is no longer possible to observe such an unambiguous picture (

Figure 11). It is definitely possible to note the growth of the separate indicators “Not all specialties can be studied remotely” and “It is necessary to have strict constant self-discipline” among all groups of students in the comparison between periods.

Figure 12 shows that the item “Rigid, constant self-discipline is necessary” increased by 15.6%, as well as the logically related item “Lack of control as a consequence of the irregular performance of tasks and more time to perform tasks” by 6.55%.

At the same time, items about real communication decreased. Thus, the “Lack of real communication” decreased by 6.59% and the “Lack of real communication with other students” by 8.48%. The rest of the items changed insignificantly.

Analyzing senior students (

Figure 13), it should be noted that the previously noted tendency to increase for the items “Strict, constant self-discipline is necessary” and “Lack of control as a consequence of irregular performance of tasks and more time to perform tasks” remained. Thus, the increases amounted to 25.83% and 11.95%, respectively.

Moreover, one more category was added in which a significant increase was observed—“Not all specialties can be studied at a distance”. The increase amounted to 17.04%.

The tendency to decrease for the items “Lack of real communication” and “Lack of real communication with other students” was present but was less pronounced. Thus, the changes amounted to 7.37% and 4.08%, respectively.

Analyzing the Master’s degree students (

Figure 14), it should be noted that the previously noted tendency to increase for the items “Strict, constant self-discipline is necessary” and the “Lack of control as a consequence of the irregular performance of tasks and more time to perform tasks” remained. Thus, the increases amounted to 18.59% and 14.13%, respectively. Thus, we can say that they were peculiar to all the categories considered.

Similarly to senior students, the percentage of choosing the option “Not all specialties can be studied at a distance” also increased. The growth amounted to 4.46%.

At the same time, the previously noted tendency about personal communication in this group changed. Thus, the option “Lack of real communication with other students and classmates” did not receive a significant change in the percentage. The option “Absence of real communication” increased in contrast to the cases considered. The growth amounted to 8.72%. In this group, there was an increase in the percentage for the category “Distance learning is mainly in written form, which hinders the development of communication and speech skills” by 7.5%. In other groups, this category had no significant differences.

The influence of “erroneous expectations” noted earlier when analyzing advantages can also be observed when analyzing disadvantages. Turning to the specific reasons why students identify significant disadvantages of switching to distance lectures and seminars, we once again see a discrepancy between their expectations and what, in fact, each of them faced. Subsequently, after returning to real university studies, the view on this class format was revised. A new paradigm has been introduced into the worldview of students and their attitude toward digital education, based not on expectations (which are present at the initial stage of learning). At this stage, students objectively assess the infrastructural challenges and interpersonal communication problems they have encountered during distance learning.

4. Discussion

The discussion takes a closer look at previously established trends. Our study has shown the value of a hybrid approach, in which it concurs with the findings of Topping [

29]. However, while Topping [

29] concludes that online learning is slightly superior to traditional methods in terms of cognitive performance, our study reveals the necessity of combining digital technologies with practical components to enhance the effectiveness of engineering education.

Our findings are consistent with previous findings in engineering education research, confirming the observed problems of distance learning in practice-intensive disciplines. Thus, distance learning as a forced measure is addressed by the work of Thamri et al. [

38], emphasizing that most students would prefer a hybrid format (54%). Our study identifies similar problems, such as technical difficulties, reduced interaction with teachers, and social isolation, but our study emphasizes the need to adapt distance technologies to the specifics of engineering education, while Thamri et al. [

38] focus on the general dissatisfaction of students with the online format and the need to reconsider strategies for its integration into the learning process.

In contrast to our study, which examines the dynamics of students’ attitudes, motivation, and adaptation to distance learning, Al-Rawashdeh et al. [

45] conclude that e-learning is generally well received by students, despite certain barriers, such as social isolation and technical difficulties. In our study, on the contrary, e-learning is less well perceived, especially among engineering students, for whom the practical component plays a key role. The main difference in the findings is that Al-Rawashdeh et al. [

45] emphasize the potential of e-learning as a long-term learning tool, whereas our study points to the need for blended learning formats to enhance the effectiveness of engineering education.

The study by Aihara et al. [

31] emphasizes that distance learning has contributed to the accessibility of education through the flexibility of formats, but has significant drawbacks. They note that 52% of instructors recorded an increase in attendance in the distance format, while comprehension increased for only 30% of students and decreased for 12%. In contrast, the students in our study indicated a decrease in engagement and difficulty in mastering the material due to lack of face-to-face contact with faculty and peers. This difference can be explained by the fact that instructors evaluate effectiveness from the perspective of managing the learning process, while students evaluate it through the prism of perceived convenience and motivation. Another difference is in the assessment of the amount of assignments. In a study by Aihara et al. [

31], 44% of instructors reported an increase in the number of pre-math assignments, which was attributed to the need to monitor student performance in a distance learning environment. In our study, students also noted the increased academic load, but it was perceived as an additional pressure rather than as a tool to improve the quality of learning.

These findings are not only relevant in the pedagogical context but also contribute to the discussion on building sustainable education systems. In alignment with SDG 4 (“Quality Education”), which emphasizes inclusive, equitable, and resilient learning environments, our results highlight the importance of integrating digital strategies that are adaptable to diverse student needs and systemic challenges. This also reflects current policy developments in the European Union, which emphasize environmental sustainability and digital readiness in educational systems [

60]. By understanding how students’ perceptions of distance education evolve, institutions can align their digital strategies with the broader sustainability goals promoted in both national and international agendas.

Furthermore, we would like to show those identified, clearly expressed advantages and disadvantages, which we managed to accumulate in the percentages in

Table 1 and compare them with those patterns that we identified in the course of our study.

4.1. Advantages

Analyzing the answers of respondents of both stages of the survey, it can be noted that, despite the differences in percentage values, the general order of distribution of benefits remains constant. Earlier in the paper (

Table 1), a table of results of similar studies was presented, which can be compared with the obtained results. In order to compare the obtained results, conversion of the indicated options into categories is necessary according to the

Section 2, which allows a direct comparison of the results of different surveys.

Table 3 presents a comparative analysis of the key advantages of distance learning across various studies, including the results of our research. The categories of time savings, qualitative improvement in the educational process, and the individualization of learning are considered the main positive aspects of distance education, but their significance varies depending on the source.

Having compared the results of the respondents from the previously considered studies, it can be noted that they practically do not change in all considered cases. At the same time, it should be noted that in the table, there are also humanitarian directions. Hence, we can conclude that students, regardless of the technical base of the university, specifics of specialty, and year of study, equally present the advantages of distance education.

First and foremost, time savings stand out as a significant advantage recognized in most studies, though it was not always ranked as the leading factor. Our data indicate that students do appreciate the flexibility of scheduling; however, not all studies highlight this advantage as a key benefit. For example, in [

45], this factor was not identified as a significant advantage at all, whereas in [

38,

41,

42,

44], it is acknowledged as one of the most important. This discrepancy may be attributed to the fact that some studies analyzed groups of students with different educational priorities: for some, access to materials and teaching quality were more important than scheduling flexibility.

The second important aspect is the qualitative improvement in the educational process, which is generally regarded as a secondary advantage in most studies, including ours. While distance learning technologies provide broad access to educational materials and digital tools, not all students perceive a real improvement in the quality of education. Specifically, studies [

41,

42,

43,

46] confirm that digital educational platforms offer students more resources and opportunities; however, this does not always lead to increased learning satisfaction. In our study, this factor also ranked second in significance, indicating the presence of both positive (information accessibility and multimedia resources) and negative aspects (reduced interaction with instructors and challenges in practical training). Similar conclusions are supported by [

38,

45], where the authors note that digital learning technologies do not always compensate for the lack of a traditional educational experience.

Finally, the individualization of the learning process received the most consistent evaluation in all studies where it was considered. In studies [

38,

41,

42], this aspect consistently ranked third, confirming its recognition within the educational environment. However, in [

45], its significance was rated lower, which could be attributed to the characteristics of the respondent sample or the specifics of the educational programs. In the distance learning format, students indeed have the ability to work at their own pace, choose convenient time slots for studying, and follow personalized learning trajectories. However, our study suggests that individualization is perceived more as a means of enhancing comfort rather than as a factor that fundamentally improves the learning process.

A comparative analysis of respondents’ responses regarding the perceived benefits of distance learning revealed a noticeable trend that has not been widely covered in previous sociological studies. Specifically, senior and Master’s students in the second wave of the survey reported a decrease in their ratings of almost all the benefits of distance learning, with the exception of “No need to spend time on commuting to the place of study.” In contrast, first-year students in the second wave of the survey demonstrated an increase in their ratings of all the benefits compared to the first stage of the survey.

This shift indicates that students’ attitudes toward distance education change as they gain more experience in higher education. An important factor influencing these perceptions is the background of first-year students in the second wave of the survey: these people were still in high school during the pandemic, meaning that their initial experience of distance learning was at the secondary level. The data suggest that those who had their experience of distance learning primarily in a university setting tend to evaluate its benefits more critically than those whose first exposure to it occurred in high school.

This discrepancy highlights the role of expectations in shaping students’ perceptions. First-year students who had formed their expectations based on school-level distance learning tend to evaluate online education in higher education more favorably. In contrast, senior students who had first-hand experience with the technical and social challenges of online learning at the university level adjusted their perceptions based on their actual experience rather than their previous assumptions. This finding highlights the importance of practical experience in determining how students perceive the benefits and limitations of distance education.

In addition to the previously discussed hierarchy of benefits, it is also worth noting the percentage change between categories in the individual groups. For example, the difference between the group of first-year respondents is the fact that the period of distance learning was in school. In addition to the comparative increases in absolutely all items, it should be noted separately the most significant change in the numerical indices of the items “Flexibility in planning training” and “Speed of communication”. Most likely, these increases are due to positive attitudes based on school experience, which students project onto higher education. However, in order to assess how fair such a judgment is, turning to the dynamics of senior students, who managed to catch the transition to distance education at the university, is necessary.

Thus, the opposite picture is observed among third–fifth-year students. Expectations for all points decreased, which indicated that the expectations were partially not met and the actual process was associated with a large number of problems. Of course, some of them can be explained by the system’s unpreparedness for such an abrupt and widespread transition, but some of these problems may also be of a fundamental nature related to the format itself.

The most mixed group in this survey were Master’s degree students. Their opinions on a part of the items had significantly changed to a greater or lesser extent. This was most likely due to the specifics of the Master’s program of study, which involves active independent work with the scientific literature.

Thus, the comparative analysis demonstrates that while distance learning indeed offers several objective advantages, students’ perception can vary significantly depending on the context, field of study, and students’ level of educational preparation. This underscores the need for further research into the conditions under which distance learning technologies can become a full-fledged alternative to traditional education, particularly in engineering disciplines.

4.2. Disadvantages

Analyzing the answers of respondents of both stages of the survey, it can be noted that the general order of the distribution of disadvantages varies depending on the stage of the survey and on the learner’s course. Earlier in the paper (

Table 1), a table of results of similar surveys was presented, with which it is possible to compare with the obtained results. In order to compare the obtained results, the obtained distribution was analyzed in

Table 4, which presents a comparative analysis of the most significant disadvantages of distance learning. The included categories—social factors, motivation issues, technical difficulties, field-specific challenges, and difficulties in mastering the material—reflect the key barriers students face when transitioning to an online format.

In contrast to the advantages, students, depending on local conditions, define the disadvantages of distance education in different ways. From the general table, the category “Specificity of the specialty” can be noted most clearly, since if items from this category appeared in the questionnaire, they in all cases ranked one–two in popularity among the respondents. This suggests that this category can be considered the most significant barrier to the use of distance education in the opinion of the student community. The influence of “erroneous expectations” noted earlier when analyzing advantages can also be observed when analyzing disadvantages.

One of the most frequently noted disadvantages is the social factor, which ranks second in significance in our study. Studies [

38,

43,

45] also confirm the significant impact of social isolation on the perception of distance learning, whereas in [

41,

46], this factor is considered less significant. This variation can be explained by the fact that the degree of social isolation may depend on the course structure: in more interactive formats (e.g., humanities disciplines), the lack of live communication has a stronger impact on student satisfaction.

Motivation issues are also among the key disadvantages, particularly in our study and in works [

38,

44], where this factor ranks third–fourth in importance. Thus, in the first stage of the survey, we can clearly see the dependence that the problems of self-discipline are paid attention to mainly by first-year students, to a lesser extent by senior students, and less by Master’s degree students. However, when comparing with the second stage, we see a significant increase in the percentages of all groups in the items “Lack of control as a consequence of the irregular performance of tasks and more time to complete tasks” and “Need for strict, constant self-discipline”. And, the latter increased by about 10–20%, depending on the group. This indicates a clear underestimation of the effort required in self-study.

Low student motivation in distance learning is attributed to the reduction of external control and the need for greater self-organization, as confirmed by the findings in [

46], where this factor also holds a high position. However, in [

41,

42,

43], motivation was not identified as a significant barrier, which could be explained either by the specifics of the student sample or differences in the research methodology.

Technical difficulties, while an important issue, hold different rankings across studies. In our research, they rank third, which aligns with the findings in [

38,

43,

44], where this factor is also among the most significant. However, studies [

41,

46] do not consider technical problems as a major barrier, which may be due to better infrastructure in the respondent samples or varying levels of students’ technical preparedness.

The category of field-specific challenges is represented in our study as well as in [

43,

44,

46], emphasizing the importance of this factor, particularly for engineering and practice-oriented disciplines. Among senior students, there is a very significant increase in the item “Not all specialties can be studied remotely”, which indicates the presence of a number of features with which students have real experience. At the same time, this growth is insignificant among first-year students, which is explained by the fact that they passed the period of distance learning at school and could not assess the real difficulties of studying in higher education in the engineering specialty, unlike humanities disciplines, where the distance format allows for a more efficient implementation of the educational process, as engineering education requires a significant number of laboratory sessions and hands-on practice, making distance learning less suitable.

The social factor items overwhelmingly show decreases, with the exception of Master’s students.

In addition, our study specifically focused on engineering students, which revealed some unique challenges during emergency distance learning due to the extensive practical components of their studies. Meanwhile, many studies show challenges for students in other fields (e.g., humanities rely heavily on theoretical learning [

21] and have had an easier time transitioning to an online format [

61], while medical education includes clinical training [

43], which also created challenges in interrupting real-world interactions [

59]).

Finally, difficulties in mastering the material are a significant factor in several studies, including [

38,

43,

44,

45], where they hold high positions. This is due to the fact that in an online format, it is more challenging to establish effective feedback between students and instructors, as confirmed by our research results, where this aspect was also highlighted as an important barrier.

Thus, the comparative analysis shows that despite its advantages, distance learning faces several systemic disadvantages, with students’ perceptions depending on the specifics of the disciplines, the level of technical support, and the structure of the educational process. This confirms the need for further research and the development of adaptive methodologies that take into account the characteristics of various educational programs.

5. Conclusions

The present study analyzed the dynamics of students’ perceptions of distance education, focusing on both the perceived advantages and disadvantages over time. Based on a comparison of two survey stages and the related literature, several key trends were identified.

Students consistently noted three principal advantages of distance learning: time saving, qualitative improvements in the educational process, and individualization. These categories remained dominant throughout the study period and across academic years. Interestingly, the perceived value of these advantages was not significantly influenced by the local institutional context. However, the comparison between two groups of respondents—those who transitioned to distance learning during their university studies and those who first encountered it in school—revealed divergent trajectories. University-level students reported a decline in their evaluations of the benefits, while school-exposed respondents demonstrated increased expectations. A notable exception was observed among Master’s students, likely due to substantial differences in their program structure compared to undergraduate or specialization tracks.

Despite these shifts in intensity, the relative ranking of the perceived advantages remained stable across groups. In contrast, the disadvantages of distance learning appeared to be more context-dependent and sensitive to both institutional and individual variables. While five major categories of disadvantages were identified—social factors, motivation issues, technical difficulties, disciplinary specificity, and challenges in mastering the material—their relative importance varied substantially depending on the university, field of study, and academic year. Among these, the “Specificity of the specialty” emerged as the most commonly cited disadvantage across multiple data points.

Furthermore, the hierarchy of disadvantages was not uniform: it changed with the students’ progression through the curriculum and in response to specific situational conditions. Given this variability, it is not feasible to propose a universal hierarchy of disadvantages. Instead, the findings from the first stage of the study may serve as a tentative reference, where students emphasized the importance of specialty specificity, followed by social interaction, technical barriers, and motivation. Notably, the category “Difficulties in mastering the material” was absent from that stage of the survey.

This study provides a methodological foundation for further empirical investigations on the perception of distance learning, particularly in engineering education. While the findings are rooted in data from a specific academic domain, the analytical approach—focused on structuring and generalizing sociological survey data—can be adapted to other disciplines. We acknowledge that the focus on engineering students limits the generalizability of the findings, especially for fields where hands-on training is less central. Nevertheless, the proposed comparison-based framework may serve as a tool to explore students’ perceptions across educational contexts.

Importantly, the results reveal that the disadvantages of distance education provide a more accurate reflection of structural and psychological challenges than the advantages, which tend to reflect generalized expectations. This distinction is critical for shaping policy and institutional strategies. A comprehensive understanding of barriers—such as motivational decline and discipline-specific limitations—requires not only the collection of survey data but also its systematic alignment across time and student groups.

The findings also emphasize the need to design learning environments that are flexible and responsive to student progression, academic specificity, and institutional infrastructure. Such responsiveness is essential to building resilient and equitable educational systems, which is central to the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 4 (Quality Education). As educational systems worldwide continue to digitize, understanding students’ changing expectations will be essential for promoting sustainable and inclusive education.

Future research should further examine how factors such as disciplinary orientation (e.g., technical vs. humanitarian focus), institutional resources, and the stage of academic training affect the perceived hierarchy of disadvantages. These dimensions are critical to informing adaptive strategies that support quality, equity, and sustainability in digital higher education.