Abstract

The sustainable protection of cultural heritage is essential for the intergenerational transmission of cultural diversity and represents a central theme in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) on “heritage resilience governance”. To address the policy sustainability challenges of large-scale linear heritage governance, this study examines the characteristics and shortcomings of Great Wall Cultural Preservation (GWCP) policies during its steady implementation. To analyze how policy instruments are distributed, whether policy objectives are synergistic, and whether stakeholders’ participation is reasonable, this study uses GWCP policy texts issued by China from 2006 to 2024 as research objects and establishes a three-dimensional analytical framework (“instrument–objective–stakeholder”). With the help of the NVivo 20 tool, the study analyzes the policy texts in one dimension and multiple dimensions, and finds that China’s GWCP policy has shortcomings in sustainability governance, such as the imbalance in the use of policy instruments, the overflow of contextual policy instruments, the government’s over-exertion of force, the need to release the functional space of stakeholders, and the lack of attention to the synergy between the goals of conserving architectural heritage and safeguarding the Great Wall ethos. Based on these findings, the study proposes three targeted optimization recommendations. This GWCP case study offers developing nations insights into balancing heritage protection objectives under SDG 11.4 with local development needs.

1. Introduction

The sustainable protection of world cultural heritage is a global governance challenge that humanity faces in the era of globalization. In November 1972, the “World Heritage Convention” established an international legal framework to protect heritage sites based on their “outstanding universal value”—specifically, cultural and natural heritage (World Heritage Committee [WHC], 1972: Preamble) [1]. The WHC assigned contracting states the responsibility for World Heritage sites and mandated them to implement comprehensive policies for heritage protection, conservation, and public engagement. (Article 5 of the WHC, 1972). In September 2015, the United Nations Sustainable Development Summit adopted the United Nations SDGs, and in November, the WHC expanded its expectations for contracting states. During the 20th session of the General Assembly of the WHC, a resolution was passed to integrate sustainable development into World Heritage conservation practices (WHC, 2015a, 2015b) [2,3]. “Consequently, the sustainable protection of world cultural heritage has become integral to achieving SDG 11.4, which calls for strengthening efforts to “protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage” through inclusive governance and policy innovation.”

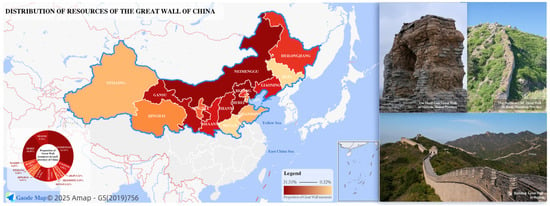

The Great Wall of China is among the first cultural heritage sites designated by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Stretching over 21,000 km across 15 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities, it traverses diverse ecological landscapes, including deserts, plateaus, and agricultural regions. As it is the most extensive and widely distributed linear cultural heritage site in China, its preservation presents significantly greater challenges than those of individual heritage structures. (The distribution of Great Wall resources by provinces in China and the representative points is shown in Figure 1). Its unique geographical span, vast architectural scale, and profound cultural significance render it an irreplaceable component of global cultural heritage [4]. UNESCO describes the Great Wall as a “global heritage that transcends cultural boundaries”. Beyond serving as a symbol of Chinese civilization and social transformation, it is also recognized by the international community as a testament to human resilience and collective endeavor, embodying both historical legacy and cultural symbolism.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Great Wall resources by provinces in China and the representative points.

With growing global awareness of cultural heritage protection, the Chinese government has increasingly recognized the Great Wall’s vital role in the nation’s culture and history. Consequently, a series of policy measures have been implemented. Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the Great Wall has been a focal point for the Party Central Committee and the State Council. Starting in 1961, key sections of the Great Wall were progressively designated as national key cultural relic protection units. In 1984, Comrade Deng Xiaoping led comprehensive efforts to protect the Great Wall. In 1987, it was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Then, in 2006, the State Council enacted the “Great Wall Protection Regulations”, which clearly outlined the legal responsibilities of various levels of government and relevant departments in safeguarding the Great Wall [5].

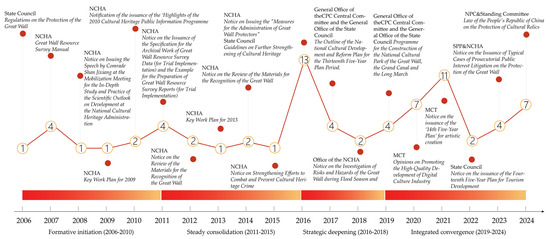

According to the statistics on the cultural protection policies of the Great Wall of China since 2006, their evolutionary dynamics can be categorized into four phases: “formative initiation stage” (2006–2010), “steady consolidation stage” (2011–2015), “strategic deepening stage” (2016–2018), and “integrated convergence stage” (2019–2024). The “formative initiation stage” aimed to clarify protection responsibilities, conduct resource censuses, assess the current status, and improve regulatory frameworks to establish foundational safeguards. The “steady consolidation stage” focused on integrating resource survey standards, issuing protection guidelines, and advancing standardized execution of conservation efforts. The “strategic deepening stage” emphasized phased planning and monitoring mechanisms to ensure effective implementation of measures while enhancing scientific rigor and efficiency. The final “integrated convergence stage” policy is based on the protection of the Great Wall architecture itself, strengthening the development and publicity of the Great Wall’s cultural resources, promoting the in-depth integration of culture and tourism, and facilitating cultural inheritance and economic development [6]. Thus, the Chinese government has demonstrated significant policy-level emphasis on GWCP. However, the effectiveness of these policies, their responsiveness to socio-cultural needs across historical periods, and their implementation processes and actual impacts require systematic examination and analysis.

Although the international community has reached a policy consensus centered around the WHC, challenges in the sustainability of cultural heritage protection remain prominent [7]. These challenges include the tension between the technical rationality of policy instruments and the cultural logic of living heritage transmission, the difficulty in balancing the long-term objectives of heritage preservation with the innovative transmission of heritage resources, and the fragmentation of governance caused by competing interests among multiple stakeholders. In this context, developing an analytical framework for “policy sustainability” and proposing policy recommendations to promote sustainability have become essential for addressing the “protection–development” paradox in cultural heritage. The trend of policy scientization requires the construction of a holistic policy analysis framework to better understand the correlation and independence between dimensions. Single-dimension analysis lacks a dynamic evolution perspective, and the three-dimensional analysis framework is the classic structure of policy research, with the advantages of clarity, strong logic, and structure. Therefore, this study breaks through the single instrumental perspective; takes the policy of GWCP of China as the research object to construct important analytical dimensions; reveals the matching mechanism of the combination of instruments, the level of objectives, and the degree of participation of the stakeholders; applies the method of analyzing the content of the policy text; establishes the three-dimensional coding system; and constructs the three-dimensional analytical framework of the policy text, which is “instrument–objective–stakeholder”. The frequency distribution and synergy frequency of each dimension in the policy texts from 2006 to 2024 have been calculated to clarify the cross-dimensional relationship, which is conducive to the evaluation and optimization of policies. This study tries to answer the following questions: First, how are policy instruments distributed in GWCP policies, and are there instruments–use imbalances? Second, are there synergies between existing policy objectives, and does their prioritization affect the sustainability of conservation policies? Third, is the participation of the various stakeholders involved in the policy reasonable, and is there an imbalance in the distribution of power or responsibility? Finally, what is the correlation between the three-dimensional interactions in the GWCP policy system?

This study employs a three-dimensional cross-analysis of policy texts to address two key research gaps. The first gap is to analyze how to balance the configuration of policy instruments, objective setting, and stakeholder collaboration in protecting the Great Wall’s cultural heritage to meet the sustainable conservation demands of large-scale linear heritage. The second gap is to explore how China’s experience with the Great Wall can offer policy insights for global heritage governance, particularly for developing countries managing cross-regional cultural heritage. The findings suggest several actionable policy recommendations, including optimizing the mix of policy instruments, coordinating policy objectives, and balancing stakeholder representation. These recommendations aim to bridge the gap between the universal principles of global heritage governance and localized practices, providing both theoretical and practical support for achieving SDG 11.4.

2. Literature Review

Building on existing literature, this study categorizes research on GWCP into three main areas. The first area addresses global cultural heritage protection policies, while the second focuses on China-specific policies for the Great Wall’s protection. The third area is the study of the preservation of the architectural heritage of the “Great Wall type” on a global scale. By combining research findings from these areas, the study offers a clearer understanding of the interplay between cultural heritage protection and policy. This framework establishes a theoretical foundation for developing a scientific and standardized policy system for safeguarding the Great Wall’s cultural heritage, while also offering key insights for refining policy instruments for cultural heritage protection in the contemporary era [8].

2.1. Research on Cultural Heritage Protection Policies

The WHC distinguishes between cultural heritage and natural heritage. Cultural heritage protection policies encompass strategies developed by nations or regions to ensure heritage conservation. Early policies prioritized emergency preservation and restoration of individual structures, exemplified by the Venice Charter (1964). By the late 20th century, attention shifted toward integrated cultural landscape conservation, as reflected in UNESCO’s 2005 revision of the Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the WHC. In the 21st century, the “Living Heritage–Community Development–Policy Innovation” model emerged [9], emphasizing a more dynamic and community-centered approach to heritage management. Subsequently, extensive academic research has explored cultural heritage protection policies across different national contexts. At the macro level, Pickard [10] analyzed the challenges and mechanisms of cultural heritage management in China, Spain, Switzerland, the UK, and the US, identifying substantial variations in national heritage protection frameworks. His findings highlight common challenges, including navigating the tension between economic growth and heritage preservation, climate change impacts, and inadequate monitoring systems. Zhang [11] mapped the historical evolution and structural framework of US heritage protection policies and compared their mechanisms with those of the UK, France, and Japan. Wang [12] categorized China’s cultural heritage protection system into three levels: protection of cultural relics and designated heritage sites, preservation of historical and cultural districts, and safeguarding historical and cultural cities. Thatcher [13] and Park [14] examined the role of cultural heritage policies as instruments of ideological governance, particularly their connections to populist and nationalist agendas. Foradori et al. [15] assess the progress of the EU’s engagement in cultural heritage protection in conflict zones within the framework of the Common Security and Defense Policy and point out that its “cultural peacekeeping” operations need to increase capacity and political commitment in order to realize their potential for leadership. At the micro level, using Safranbolu (Turkey) and Sri Ksetra (Myanmar) as case studies, Cabbar [16] and Liljeblad [7] emphasize the critical roles of financial support, regulatory improvements, and community participation in cultural heritage protection, proposing context-specific strategies for sustainable development in their respective countries. Wei [17] and Shen [18] analyzed registration and tax incentive systems in the UK, Japan, South Korea, and the US, proposing a sustainable strategic framework and adjustments to tax policies to enhance the protection, utilization, and renewal of China’s historical and cultural heritage. Bagade [19] examines the evolution of Saudi Arabia’s architectural heritage conservation policy through the Jeddah Fortification Wall case study. Separately, Owley [20] critiques the privatization model of conservation easements, arguing that it undermines public participation, entrenches intergenerational inequities, misallocates resources, and commodifies cultural heritage. Lekakis [21] highlights that Greece’s hasty integration into the conservation system since the 1950s caused public alienation, fostering passive or utilitarian participation patterns that jeopardize the heritage’s survival.

2.2. Research Related to the Protection of the Great Wall Culture

The research on the cultural preservation of the Great Wall is mainly divided into the following levels. Firstly, the research on Great Wall architectural heritage protection: Zhang Zhi et al. [22] proposed a digital twin framework for Great Wall cultural heritage protection, exploring methods, applications, and trends. Yu Bing [23] proposed that the overall protection of the Great Wall faces the challenges of difference and decentralization. Ren Yunlan [24] and others analyzed Great Wall resources by section, proposing specific protection measures. Secondly, research on Great Wall culture dissemination: Chen Yu [25] analyzed the ambiguous problem of Great Wall culture cognition and put forward the path of Great Wall culture publication and dissemination based on community consciousness. Zhou [26] examined museums along the Great Wall, identifying key issues and strategies for cultural dissemination. Peng [27] emphasized the cultural value of the Great Wall National Cultural Park, proposing communication strategies through cultural space and IP development. In addition, there is also research on the Great Wall culture and tourism integration: Liu [28] developed a theoretical method to evaluate the impact of cultural heritage on rural tourism, offering planning strategies for socio-economic development in Great Wall villages. Cheng [29] analyzed cultural and tourism resources along the Hebei section, proposing effective strategies for tourism utilization.

2.3. Research Related to the Preservation of the “Great Wall-Type” Architectural Heritage in the Global Context

Other regions worldwide feature defensive structures similar to the Great Wall, such as Hadrian’s Wall in England and the Germanic Limes in Germany. Compared to Chinese scholars, international scholars emphasize evaluating the cultural heritage value and applying conservation techniques in studies of Great Wall-type architectural heritage preservation globally. Peter Spring [30], in Great Walls and Linear Barriers, analyzed the form, strategic function, and distribution patterns of Hadrian’s Wall and other Roman Empire border barriers. Warnaby [31] developed a dynamic management model for Hadrian’s Wall based on value assessment, emphasizing the balance between conservation and use through proactive planning, multi-stakeholder collaboration, and local adaptation principles. Guzman [32] linked SDG 11 and SDG 13 to assess correlations between development factors and cultural heritage protection using localized indicators. Božić et al. [33] established the Cultural Route Evaluation Model (CREM) using Serbia’s Roman Emperor’s Route as a case study, evaluating heritage based on main and added values. In sustainable cultural heritage tourism, Daniela [34] employed digital tools to enhance heritage environment design, creating interactive installations that allow visitors to assume the roles of Romans living along Hadrian’s Wall. Guiver [35] addressed sustainable travel on Hadrian’s Wall, arguing that methods used to improve the environmental sustainability of utility travel require adaptation for leisure contexts. In stone heritage conservation, Gifu et al. [36] reviewed polyelectrolyte applications, focusing on their use in preservation, curing, and cleaning of stone and organic materials. Peng et al. [37] advanced intelligent detection technology—including hyperspectral imaging and a deep-learning radial basis function compression algorithm to improve the accuracy and efficiency of identifying deterioration in stone relics.

In conclusion, research on cultural heritage protection policies is relatively abundant, encompassing cross-country comparisons, adjustments to policy tools, critical reflections, and other areas. However, due to substantial and significant differences in governance mechanisms across countries, there is a lack of policy research offering globally applicable governance models for linear cultural heritage. From the perspective of research objects, in studies on the protection of China’s Great Wall culture, scholars typically focus on heritage preservation, cultural dissemination, and the integration of cultural tourism. However, research at the policy level remains scarce, lacking comprehensive, systematic analyses, and the elements of the policy structure have not been fully defined. From the research methodology, most current studies on the Great Wall’s culture rely on qualitative analysis, with limited quantitative research that could uncover the internal logic and dynamic effects of policy evolution. From a research perspective, the international academic community has long neglected the specificity of cross-regional linear defense heritage governance in developing countries and has yet to establish an “instrument–objective–stakeholder” adaptation framework tailored to such governance contexts. How can we clarify the current structure of policy instruments, trace the policy objectives, and assess the rationality of stakeholder participation using a sound analytical framework and scientific quantitative methods? This remains a critical gap in the existing literature. Therefore, compared to the theoretical fragmentation and lack of quantitative research in existing cultural heritage policy studies, combined with the scarcity of policy studies focusing on China’s Great Wall, this study seeks to depart from traditional approaches by systematically collecting and analyzing GWCP policies. Using policy instrument theory, this study conducts a contextual evolution and quantitative analysis of policy texts, proposing a three-dimensional framework of “instruments–objectives–stakeholders” to provide a new theoretical foundation for understanding the sustainability of cultural heritage policies.

3. Analysis Framework and Data Collection

3.1. Three-Dimensional Analysis Framework Construction

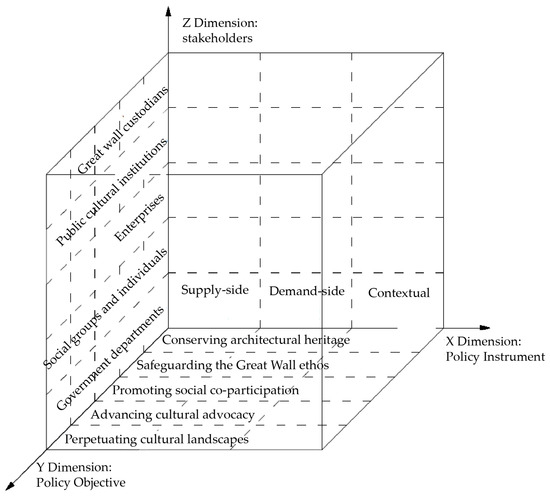

3.1.1. X Dimension: Policy Instruments

Policy instruments refer to the set of means and measures designed by policymakers to achieve specific policy objectives. In this study, they refer to the series of specific measures formulated by the government to promote the GWCP. Whether the government can scientifically and rationally select policy instruments and adjust and improve them according to actual conditions is crucial to the effectiveness of policy implementation and the achievement of policy objectives [38]. This study adopts the classification of policy instruments proposed by Rothwell and Zegveld, dividing them into supply-side, demand-side, and contextual policy instruments [39].

Supply-side policy instruments involve government or relevant agencies expanding the supply of key resources to promote the protection of the Great Wall’s cultural heritage. These instruments serve as catalysts and include talent development, technical support, financial assistance, rewards and subsidies, infrastructure, industrial support, information sharing, and resource integration [40].

Contextual policy instruments refer to the various means employed by the government to create a favorable policy environment for the protection of the Great Wall and the promotion of its culture. These include cultural tourism spaces, standards and norms, objective planning, implementation strategies, supervision and inspection, regulatory control, and institutional capacity strengthening.

Demand-side policy instruments are those that actively mobilize the government, corporations, and the public to participate in the GWCP, thereby fostering broader and deeper societal demand for its cultural preservation. These instruments act as pull factors and include publicity and education, market improvement, demonstration pilots, social participation, public services, academic research, and international exchanges.

3.1.2. Y Dimension: Policy Objectives

Policy objectives refer to the intended goals and outcomes that policymakers aim to achieve through policy implementation [41]. Based on the “Overall Plan for Great Wall Protection” and the “China Great Wall Protection Report”, this study identifies five primary objectives for GWCP:

Firstly, safeguarding the Great Wall ethos: this involves employing various approaches to enhance the influence of the spirit of the Great Wall across society, ensuring the transmission of its spiritual values. Secondly, advancing cultural advocacy: this entails introducing the cultural landscapes and historical significance of the Great Wall to global audiences, alongside showcasing the advanced principles employed by the Chinese government in its protection and management efforts, thereby presenting an authentic and comprehensive representation of China’s cultural heritage. Thirdly, conserving architectural heritage: this focuses on preserving the physical relics of the Great Wall from different historical periods, enhancing regular maintenance, and promptly addressing safety risks posed by both human and natural factors. Additionally, perpetuating cultural landscapes: This involves protecting the unique cultural and ecological systems, as well as the landscape features shaped over two thousand years of Great Wall construction. It also includes safeguarding local traditions and customs, regulating tourism and development activities, and ensuring a harmonious balance between preservation, ecological protection, and local socio-economic development. Finally, promoting social co-participation: this aims to enhance public engagement in Great Wall conservation, fostering a collective sense of responsibility for cultural preservation and strengthening the social foundation for sustained protection efforts.

3.1.3. Z Dimension: Stakeholders

Stakeholders refer to the stakeholders involved in the policy implementation process [42]. The cultural preservation of the Great Wall is a large and complex initiative that requires extensive participation from multiple stakeholders, working together to form a closely-knit network of actors. Considering the roles and functions of each stakeholder in GWCP, this study identifies five primary stakeholder categories.

Firstly, government departments: various governmental bodies at all levels are responsible for deploying and implementing the GWCP policies. Secondly, social groups and individuals: individuals who provide support for the cultural preservation of the Great Wall. A third layer involves enterprises: business entities engaged in activities related to the Great Wall’s cultural heritage. Fourth in sequence, public cultural institutions: non-profit organizations focused on the preservation of the Great Wall’s culture. Finally, Great Wall custodians: individuals, including protectors and volunteers, employed by county-level local governments or relevant departments to patrol and protect the Great Wall. The X-Y-Z three-dimensional analysis framework for the text of GWCP is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

X-Y-Z three-dimensional analysis framework for the text of GWCP.

3.2. Policy Data Selection and Coding

3.2.1. Policy Text Selection and Preprocessing

To ensure the accuracy and representativeness of the policy sample, this study used keywords such as “Great Wall” and “Preservation of the Great Wall Culture” to search official platforms, including Peking University’s Legal Information Database, the State Council Policy Document Library, China Government Network, the National Cultural Heritage Administration (NCHA), and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism (MCT). An initial selection yielded 165 public policy documents. The final selection was based on four key criteria:

Primarily, relevant policies from the central level were selected, with a focus on documents issued by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, the State Council, and its subordinate ministerial agencies. Subsequently, the selected policy types included laws, administrative regulations, and ministerial normative documents. Local policies, approvals, letters, and other informal documents were excluded, leaving only documents with legal authority, such as laws, regulations, notices, opinions, and guidelines. Furthermore, only policies that are currently valid were included, while duplicate, irrelevant, and low-relevance policies were excluded. And then, based on the characteristics of GWCP, procedural documents such as protection lists, meeting notices, and application notices were further excluded.

Since the “Great Wall Protection Regulations”, promulgated in 2006, are the first laws targeting Great Wall protection and outline the legal responsibilities of various levels of government and departments, which have significantly guided the formulation of subsequent policies, the search period was set to conclude by 31 December 2024, with the time span for the policy documents being from 2006 to 2024 [43]. After coding and screening, a total of 73 valid policy documents were finalized. These included one document from the National People’s Congress and its Standing Committee, six documents from the central government (the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council), and 66 documents from other ministries and departments, such as the NCHA, including the Regulations on the Protection of the Great Wall (2006), the Great Wall Resource Survey Manual (2007), the Guidelines on the “Four” Work of the Great Wall (2014), the Guidelines on the Protection and Maintenance Work of the Great Wall (2014), the Great Wall of China Protection Report (2016), issued by NCHA, the Great Wall Protection Master Plan, jointly (2019) issued by the MCT and NCHA, and the Typical Cases of Public Interest Litigation for Great Wall Protection Inspection (2023), issued by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate and NCHA. Representative policies, release dates, and trends are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Representative policies, release dates, and trends.

3.2.2. Policy Text Coding

Based on the selected policy sample, content analysis was performed on 73 GWCP policy documents using the qualitative analysis software NVivo 20. First, the policy texts were examined to identify policy clauses and statements that accurately reflect the themes of Great Wall protection and cultural preservation. These analytical units were then coded and categorized according to three dimensions: policy instruments, policy objectives, and stakeholders, ensuring coding reliability and categorization consistency. An example of the coding process and results for the text portion of the policy is shown in Table 1. A total of 1512 reference points were identified. Of these, 718 reference points were related to the policy instruments dimension, 381 reference points to the policy objectives dimension, and 413 reference points to the stakeholders dimension. To ensure the reliability of the coding results, the research team conducted forward and reverse coding of the analysis units at separate intervals. Discrepancies in coding outcomes were resolved through small-group discussions and expert consultations to achieve consensus. Additionally, 10% of the analysis units were randomly selected for independent coding by two doctoral students majoring in cultural heritage management. Inter-coder agreement exceeded 80% across all dimensions, confirming the reliability of the coding results.

Table 1.

Example of coding process and results for the textual part of the policy.

4. Policy Text Quantitative Analysis

4.1. Single-Dimension Analysis

4.1.1. X Dimension: Policy Instrument Analysis

Table 2 presents the distribution of encoded categories for GWCP policy instruments. Using NVivo 20’s matrix coding query function, frequency analysis, and percentage calculation were applied to systematize data across dimensions, leveraging the software’s statistical tools to analyze coding results. Descriptive statistical indicators (e.g., percentages, distribution trends) were ultimately employed to identify the structural characteristics of the policy instruments. A total of 718 coded items were identified, reflecting a wide scope of policy instruments. However, a notable imbalance exists in their distribution. contextual policy instruments constitute nearly half of the total, equivalent to the combined proportion of supply-side and demand-side instruments, accounting for 50.28% of all identified policy instruments. Despite this, their subcategories are relatively evenly distributed, with supervision and inspection (24.93%), regulatory controls (20.50%), and objective planning (15.79%) representing the largest shares. Supply-side policy instruments follow, comprising 28.13% of the total, with infrastructure (22.77%) and resource integration (20.79%) as the most prominent subcategories. Demand-side policy instruments make up 21.59%, with publicity and education (25.81%), social participation (22.58%), and demonstration pilots (21.94%) as the primary areas of focus. These findings illustrate the key distribution patterns of policy instruments in GWCP.

Table 2.

Distribution of policy instruments in dimension X of the GWCP policy.

First, China’s GWCP policy is context-driven, primarily aiming to establish a well-defined and legally structured policy framework for Great Wall conservation through comprehensive laws, regulations, and strategic planning. Additionally, supervision and inspection mechanisms—covering the Great Wall itself, its surroundings, visitor management, and safety—ensure that conservation efforts progress in an orderly and efficient manner. Moreover, the significant proportion of strategic planning policies suggests that policymakers have a clear vision for the future of GWCP. However, at the implementation level, policies lack concrete action plans, leading to weak policy execution.

Second, policies have long prioritized investment in Great Wall infrastructure, such as protective facilities and visitor amenities, while harnessing technological innovations to support conservation efforts. For instance, Gansu Province identified and restored illegal kiln holes at the base of a Great Wall beacon tower using drone inspections and AI-based analysis. Similarly, Yanchi County in Ningxia implemented sequential projects, including vegetation restoration along the Great Wall’s perimeter and the installation of protective fencing. Additionally, the county efficiently completed 3D scanning and digitized archival records of the Great Wall, its beacon towers, and adjacent ancient fortresses. Additionally, as a large-scale linear heritage site with numerous resource segments, China has emphasized cross-regional and large-scale resource integration. However, despite the rapid growth of the cultural tourism industry, policy support for cultural and tourism industries within the Great Wall National Cultural Park remains inadequate. The absence of concrete support measures could hinder the sustainable development and optimization of GWCP.

Third, demand-side policy instruments require significant strengthening, with severe imbalances among subcategories. The government must further enhance public awareness and cultivate a strong conservation culture. Due to the Great Wall’s vast scale and wide distribution, the government has implemented policy-supported demonstration projects to create benchmark conservation models at select locations. However, market development and international collaboration remain underdeveloped, limiting the effective utilization, conservation, and global promotion of Great Wall culture.

Fourth, supervision and inspection are the most widely used policy instruments, together accounting for 12.53% of the total. Between 2019–2024 alone, the Gansu provincial procuratorial authorities have initiated 185 prosecutorial supervision actions for the protection of the Great Wall and, through public interest litigation, have promoted the demolition of 52 illegal buildings within the Great Wall’s protection zones, the vacating of more than 600 acres of arable land, and the setting up of more than 600 protection markers and monuments. Whereas market development measures constitute only 0.27%, revealing a stark imbalance. This underscores the government’s strong emphasis on strict regulatory oversight but also its neglect of market-driven cultural tourism development. The over-reliance on enforcement-based policies may impede the sustainable and innovative development of GWCP. A protection-centric approach that prioritizes regulation without integrating sustainable utilization strategies may ultimately prove unsustainable as cultural preservation policies evolve to meet contemporary needs.

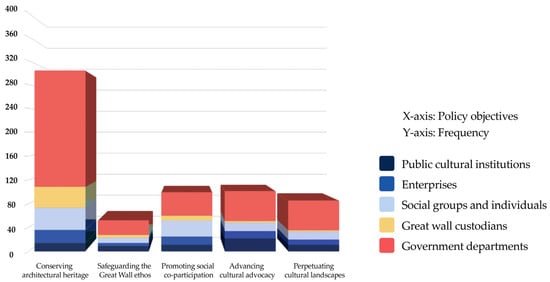

4.1.2. Y Dimension: Policy Objective Analysis

A total of 381 policy items were identified under the policy objective dimension. Among the five policy objectives, “conserving architectural heritage” was the most prevalent, accounting for 53.02% of the total. The distribution of encoded categories for GWCP policy objectives shown in Table 3. The objectives of “advancing cultural advocacy” (14.70%), “perpetuating cultural landscapes” (14.43%), and “promoting social co-participation” (10.76%) were relatively evenly distributed, while “safeguarding the Great Wall ethos” had the lowest representation at 7.09%. This distribution underscores the predominance of “conserving architectural heritage“, which aligns with the principles of scientific planning and original-state conservation, as well as the overarching objective of “protecting, inheriting, and utilizing the Great Wall effectively.” It also reflects China’s heritage conservation framework, which prioritizes “protection first, rescue as a priority, reasonable utilization, and enhanced management.” Additionally, “perpetuating cultural landscapes” remains a central objective of the government’s conservation strategy. Chinese policies have introduced sustainable development mechanisms to regulate tourism activities and ecological conservation in areas surrounding the Great Wall. However, similar to “advancing cultural advocacy” and “promoting social co-participation”, this area requires additional refinement of supporting policies and measures to enhance conservation efforts and expand stakeholder engagement. Moreover, in the “Great Wall Value” section of the Overall Plan for Great Wall Protection, the “value of embodying the resilient and indomitable spirit of the Chinese nation” is designated as the highest priority. Likewise, the China Great Wall Protection Report emphasizes that “preserving and promoting the Great Wall spirit has always been the fundamental purpose of Great Wall conservation”. However, the policy objective of “safeguarding the Great Wall ethos” has not been accorded the level of attention proportionate to its historical and cultural significance. This imbalance reveals a policy tendency favoring conservation over cultural transmission. This contradiction between “declarative importance” and “operational neglect” needs to be resolved urgently and, if not addressed, may weaken the role of the Great Wall in embodying both historical and contemporary national identity and hinder the sustainable development of GWCP [44]. For example, in 2016, the controversy over the repair of the Great Wall in Suizhong City, Liaoning Province: the Great Wall being “flattened” into a paved surface, although in line with the protection standards, was cut off the cultural perception, exposing the contradiction of “prioritizing engineering over interpretive integrity”.

Table 3.

Distribution of policy objectives in dimension Y of the GWCP policy.

4.1.3. Z Dimension: Stakeholder Analysis

A total of 413 policy items were identified under the stakeholder dimension. The distribution of encoded categories for GWCP stakeholders shown in Table 4. Among them, government departments had the highest level of participation, accounting for 57.87% of the total. This was followed by social organizations and individuals (13.32%), Great Wall protectors (10.90%), public cultural institutions (9.44%), and enterprises (8.47%). These figures reflect the predominance of a government-led approach in China’s GWCP policies, with government departments assuming a central role in overarching policy direction and regulatory oversight. Meanwhile, public cultural institutions, enterprises, social organizations, and individuals function within a state-led collaborative governance model. However, Great Wall conservation is characterized by limited proactive participation from enterprises and social organizations, where passive and mandated participation mechanisms dominate. This over-reliance on government-driven conservation approaches results in a lack of diverse management strategies and limited effectiveness in cultural promotion and public engagement.

Table 4.

Distribution of stakeholders in dimension Z of GWCP policy.

4.2. Cross-Dimensional Analysis

4.2.1. “X–Y” Two-Dimensional Cross-Analysis

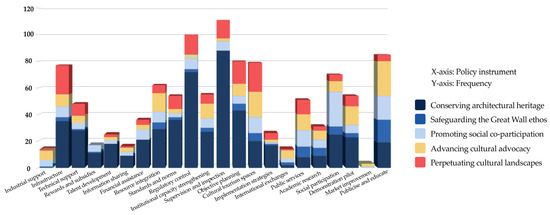

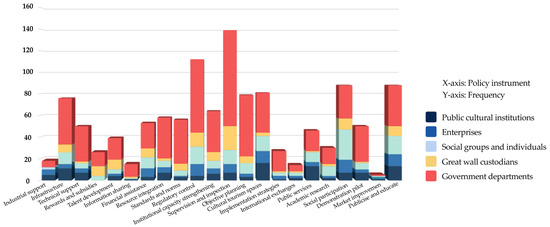

A cross-analysis of the “policy instrument–policy objective” dimensions was conducted, with the results shown in Figure 4. The realization of GWCP policy objectives employs a combination of various policy instruments; however, there is a notable imbalance in their alignment.

Figure 4.

Frequency distribution of the dimension “policy instrument–policy objective”.

Horizontally, the achievement of GWCP objectives relies predominantly on contextual policy instruments, which constitute 45.58% of total policy instrument usage. The application frequencies of supply-side (26.62%) and demand-side (27.80%) policy instruments are relatively balanced. Specifically, among contextual policy instruments, supervision and inspection and regulatory controls are the most frequently utilized. Among supply-side policy instruments, infrastructure, technical support, and resource integration apply to all policy objectives, indicating that the government’s investment in GWCP primarily targets tangible infrastructure. Among demand-side policy instruments, publicity and education play a dominant role, whereas market improvement instruments are notably underutilized.

Vertically, key objectives such as “conserving architectural heritage” and “perpetuating cultural landscapes” depend heavily on regulatory controls supervision and inspection within contextual policy instruments, highlighting an over-reliance on statutory regulations and administrative oversight. In contrast, policy objectives such as “safeguarding the Great Wall ethos”, “advancing Cultural advocacy”, and “promoting social co-participation” primarily rely on demand-side policy instruments, particularly public education, social participation, and public service mechanisms. However, the analysis also reveals a significant underutilization of supply-side policy instruments across all policy objectives. This suggests that in the implementation of GWCP policies, greater effort should be directed toward ensuring a more balanced application of supply-side instruments.

4.2.2. “X–Z” Two-Dimensional Cross-Analysis

A cross-analysis of the “policy instrument–stakeholder” dimensions (Figure 5) reveals key trends in the distribution and application of policy instruments among different stakeholders. The five stakeholder groups exhibit distinct preferences in their use of policy instruments. Government departments were the most active stakeholders, with 681 instances of policy instrument usage, accounting for 56.10% of the total. Among policy stakeholders, government departments (51.25%) and Great Wall custodians (49.17%) exhibited the highest reliance on contextual policy instruments. This suggests that the government prioritizes establishing supportive regulatory and planning frameworks to advance GWCP. Social organizations and individuals, public cultural institutions, and enterprises responded most frequently to demand-side policy instruments. Specifically, public cultural institutions played an active role in public services and public education initiatives. Enterprises had the lowest level of policy instrument engagement, comprising just 8.73% of total instances, with their involvement primarily centered on social participation. This underscores the limited recognition of enterprises’ potential contributions within existing policies. There is a pressing need to foster greater corporate involvement in innovative conservation strategies and leverage their unique strengths to enhance the sustainability and effectiveness of GWCP.

Figure 5.

Frequency distribution of the dimension “policy instrument–stakeholder”.

4.2.3. “Y–Z” Two-Dimensional Cross-Analysis

A cross-analysis of the “policy objective–stakeholder” dimensions (Figure 6) highlights significant variations in the participation levels of different stakeholders across policy objectives. As the dominant stakeholder group, government departments exhibited the highest rate of engagement across all five policy objectives, reinforcing their leading role in GWCP. However, their participation was heavily skewed toward the protection of Great Wall architectural heritage, accounting for 56.09% of their policy responses, whereas their engagement in “preserving and promoting the Great Wall spirit” was markedly lower, at just 6.96%. This suggests that government efforts are primarily directed toward the structural conservation of the Great Wall, with insufficient emphasis on its cultural and spiritual legacy. Similarly, other stakeholder groups also exhibited an uneven distribution of participation across different policy objectives. Their involvement underscores a strong emphasis on the protection of the Great Wall architectural heritage, while the transmission and promotion of the Great Wall spirit receive comparatively little attention.

Figure 6.

Frequency distribution of the dimension “policy objective–stakeholder”.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Research Conclusions

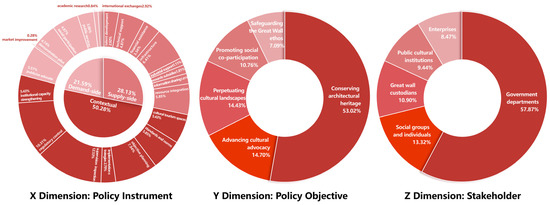

This study examines 73 GWCP policies issued by the Chinese government from 2006 to 2024, applying a three-dimensional “instrument–objective–stakeholder” analytical framework. By employing quantitative text analysis, we construct a sustainability framework based on an in-depth examination of policy instruments, policy objectives and stakeholders (see Figure 7 for the three-dimensional statistical distribution). The paper evaluates the current utilization of policy instruments and proposes recommendations for adjusting and optimizing future GWCP policies. Based on this analysis, the study’s conclusions are summarized as follows.

Figure 7.

Statistical distribution of policy instruments, policy objectives, and stakeholders.

Firstly, within the dimension of policy instruments, China’s current GWCP policies exhibit a structural imbalance in the application of policy instruments. Contextual instruments dominate (50.28%), while supply-side instruments (28.13%) and demand-side instruments (21.59%) are underutilized. Key findings from the textual data analysis include the following: First, contextual-driven conservation. The current policies prioritize legal frameworks, regulatory planning, and oversight, but lack specific implementation guidelines, weakening policy effectiveness. Second, infrastructure and technology-driven conservation. The government focuses on integrating protection facilities and resources but provides insufficient support for the cultural and tourism industry, which restricts the sustainable development of the Great Wall culture. Third, insufficient use of demand-side policy instruments. This is manifested in the weak social participation and market mechanism, the reliance on demonstration sites to lead the way, and the cultural promotion and external exchanges that need to be strengthened. Fourth, the serious imbalance between supervision and the market. From the overall viewpoint of policy instruments, supervision and inspection account for a disproportionately high proportion, and cultural tourism market development is seriously insufficient. This mode of instrument configuration reveals the deep-seated feature of China’s cultural heritage policy of “strong regulation–weak empowerment”. The supervision of the government is still an important guarantee to ensure the implementation of the GWCP work and the sustainable development of the Great Wall, while over-reliance on coercive measures will hinder the innovation and long-term development of the GWCP. In short, the low coverage of supply and demand dimensions may lead to the insufficiency of endogenous motivation of pluralistic subjects, which may affect the process of the GWCP in the case of long-term overflow of contextual policy instruments.

Secondly, within the policy objectives dimension, the study identifies a temporal tension between “entity-based” conservation and “cultural-empowerment” objectives. The GWCP policies are transitioning from a conservation-centric to an innovation-oriented strategy. This echoes Ren et al.’s paradigm revolution from material preservation to value reproduction in the protection of historical and cultural heritage [45,46] and validates the global paradigm revolution in cultural heritage protection. The Great Wall is not only a physical defense project but also a spiritual symbol and a carrier of cultural memory of the Chinese nation, as a physical expression of China’s “world philosophy”, “culture of harmony”, and the national spirit of “continuous self-improvement and unity of purpose”. Historically focused on “protection first”, policies often neglected the transmission of the Great Wall spirit and the synergy between physical conservation and cultural heritage transmission. Moreover, it has not yet emphasized the cultural phenomenon of cultural heritage as an interaction between human beings and objects, as well as the paradigm shift from “object-oriented” to “people-oriented” in the international heritage community [47]. This imbalance of objectives has led to the formation of “protection islands” of Great Wall cultural heritage, and there will be systemic barriers to its innovative transformation. However, at the integrated convergence stage, the government has sought to balance conservation and innovation, shifting the focus toward “innovative utilization” and away from “excessive protection”. This shift responds to contemporary demands for GWCP and the development of the Great Wall National Cultural Park [48], addressing the lack of cultural dynamism caused by imbalanced conservation and utilization efforts.

Thirdly, within the dimension of stakeholders, the data indicate that the participation of government departments accounts for 57.87%. The single-object model of the government has played a key role in the initial stage of GWCP, promoting the GWCP to achieve remarkable results (e.g., during the 13th Five-Year Plan period, China’s central and provincial governments invested more than 1 billion yuan per year in the Safe Cultural Relics Project). Still, its structural deficiencies have become increasingly evident as cultural preservation develops in depth, reflecting the institutional challenges of global heritage governance. Although the government established a social participation system for GWCP in 2006, the symbolic participatory framework has failed to catalyze substantive community engagement. Implementation strategies and support mechanisms remain underdeveloped, necessitating the urgent creation of a closed-loop “input–reward” incentive system to bridge gaps in collaborative governance [49]. This undermines the motivation of social groups to contribute to and engage with the Great Wall, causing conservation efforts to stagnate at the level of “maintaining the protection of the Great Wall itself”, rather than advancing toward “developing the culture of the Great Wall”. In summary, this structural transformation provides a practical pathway for advancing Great Wall conservation from “physical maintenance” to “cultural regeneration”, while simultaneously promoting sustainable protection and cultural utilization of this heritage. In the long term, the current imbalanced governance model in GWCP—characterized by excessive government dominance and limited multi-stakeholder participation—persists unchanged. Achieving true synergistic collaboration among multiple subjects and objectives remains a significant challenge requiring sustained effort.

Finally, through the three-dimensional cross-analysis of “instrument–objective–stakeholder”, it is found that, in terms of instrument-objective matching, contextual policy instruments (45.58%) are overly focused on the “hard protection” of architectural heritage, while supply-side policy instruments (26.62%) are lacking in technical support, resource integration and other long-term protection. Demand-side policy instruments (27.80%) are limited to publicity and education, but market mechanisms are not sufficiently utilized, resulting in weak results in the goal of “soft heritage”. In term of stakeholder and instrument configuration, the government relies on contextual policy instruments (51.25%) to form “single-center governance”, and the marginalization of supply- and demand-side instruments inhibits the activation of innovation factors such as social forces and enterprises. In term of interaction between objectives and stakeholders, there is an imbalance in the realization of objectives by each stakeholder, and the overall participation of government departments in policy objectives is as high as 56.09%, forming a pattern of “strong government dominance”, with a high-frequency response to architectural protection and low participation in cultural inheritance, which exposes the structural contradiction of “focusing on entities but not on spirituality”.

5.2. Suggestions

5.2.1. Optimize the Mix of Policy Instruments to Drive Sustainable Development

To address implementation gaps in contextual policy instruments, the implementation steps and responsibilities should be refined; a two-dimensional monitoring system should be established, encompassing both structural protection and policy implementation effectiveness; a third-party evaluation should be introduced; and the results should be made public to enhance transparency. In the supply-side policy instruments, the government needs to introduce specific industrial support measures, such as establishing a special fund for Great Wall cultural tourism development, and promote government–enterprise cooperation to strengthen cultural and tourism project development, jointly extending the cultural industry chain. In the demand-side policy instruments, the government should enhance the diversity and relevance of publicity and education and use digital tools for differentiated publicity-and-promotion campaigns, emphasizing the significance of protection, historical value, and spiritual connotation. For example, in French cities, cultural heritage “promoters” volunteer as local liaisons to assist schools in heritage education activities, strengthening protection awareness through community-driven communication. Meanwhile, cooperation with international organizations should be prioritized to jointly conduct conservation projects and cross-border tourism development, enhancing the international recognition and market appeal of Great Wall culture.

5.2.2. Coordinate Policy Objectives and Deepen the Living Heritage Approaches

In policy formulation, the policy supply of weak objectives should be enhanced. It is important to clarify the importance of the objective of “carrying forward the spirit of the Great Wall”, formulate specific implementation plans and focus on balancing the relationship between protection and utilization. This means that the policy should fully account for the Great Wall’s dual attributes as a cultural heritage, not only to prevent destruction from over-commercialization but also to avoid excessive preservation and neglecting its vitality as a cultural symbol and soft resource. Italy’s National Film Museum, housed within Turin’s landmark Antonelli Spire heritage site, is a vivid case in point, where audiences engage with centuries-old heritage while learning about modern art’s origins and evolution and strengthening the publicity and promotion of cultural heritage and social participation. Together with the construction of the Great Wall of China National Cultural Park, it validates the principle of “spatial function regeneration”. Therefore, it is important to maintain the vitality of the Great Wall through revitalization and utilization, preventing cultural disconnects arising from restrictive preservation and realizing the sustainable inheritance of heritage.

5.2.3. Balance Stakeholder Representation and Optimize a Diverse Participation Framework

In the formulation and refinement of GWCP policies, the “government-led, socially participatory” governance model should be reinforced. In developing countries, where regulatory dependency prevails, governments can mobilize social capital and private-sector engagement in cultural heritage transformation through cooperation agreements, joint protection organizations, and collaborative projects. This approach creates synergy for the Great Wall’s protection and development, shifting policies from administrative mandates to socially driven initiatives. For example, Italy has implemented public–private partnerships (PPPs): its Cultural Heritage and Landscape Code permits government collaboration with private enterprises in heritage protection and restoration. In 2018, fashion brand Tod’s contributed EUR 25 million to restore Rome’s Colosseum, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, establishing a business–government partnership.

5.3. Research Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study examines China’s GWCP policies through the lens of the “instrument–objective–stakeholder” framework and presents policy recommendations aimed at long-term sustainability. It proposes a novel paradigm for a hybrid methodology integrating qualitative coding of policy texts with quantitative statistical analysis, proposes sustainable policy recommendations, and offers actionable pathways for developing countries to balance “government-led” approaches with “pluralistic governance”. However, several limitations persist: (1) The study predominantly relies on national-level policy texts, with the limited investigation into localized policy adaptations and implementation challenges at the provincial, municipal, and county levels. (2) The quantitative analysis primarily focuses on observable attributes of policy instruments, objectives, and stakeholders, while underlying institutional mechanisms—such as cultural identity construction and the role of informal rules—remain underexplored. Future research should advance in two key directions: (1) Expanding research on policy processes to elucidate the sustainability dynamics of “central-local” interactions in cultural heritage preservation policies. (2) Integrating discourse analysis, ethnographic methods, and additional qualitative methodologies to investigate how implicit cultural values influence public engagement and heritage recognition through policy instruments, thereby strengthening the methodological robustness of policy design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C.; methodology and software, Z.W.; policy codes, X.Z.; policy collection, Z.W. and J.Z. (Jingwen Zhao 1); formal analysis, J.Z. (Jingwen Zhao 1); investigation, Z.W.; resources, Y.C. and W.L.; data curation, Z.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.W. and J.Z. (Jingwen Zhao 1); writing—review and editing, S.Z. and J.Z. (Jingwen Zhao 2); visualization, S.Z. and J.Z. (Jingwen Zhao 2); supervision, Y.C. and W.L.; project administration, Y.C.; funding acquisition, Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Hebei Provincial Cultural Research Special Program “Hebei Great Wall Historical and Cultural Library”, grant number HB23WH001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their time and effort devoted to improving the quality of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| GWCP | Great Wall Cultural Preservation |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| WHC | World Heritage Convention |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| NCHA | National Cultural Heritage Administration |

| MCT | Ministry of Culture and Tourism |

References

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Managing Cultural World Heritage. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/managing-cultural-world-heritage/ (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- World Heritage Committee. World Heritage and Sustainable Development, World Heritage Committee, 39th Session, WHC-15/39.COM/5D; United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/documents/137710 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- World Heritage Committee. Policy Document for the Integration of a Sustainable Development Perspective to the Processes of the World Heritage Convention; United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/documents/138856 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Liu, M.X.; Han, G.Y. A study on the current situation and problems of the Great Wall protection policy in China. J. Hebei Univ. Geol. 2017, 40, 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- State Administration of Cultural Heritage. Regulations on the Protection of the Great Wall [Order of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China (No. 476)]. Available online: http://www.ncha.gov.cn/art/2006/10/25/art_2237_33544.html (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Wang, C.; Cui, H.Q. Quantitative evaluation of rural leisure tourism policies and development outlook. J. Tour. 2024, 39, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Liljeblad, J.; Oo, K.T.T. World Heritage Sustainable Development Policy & Local Implementation: Site Management Issues Using a Case Study of Sri Ksetra at Pyu Ancient Cities in Myanmar. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 468–477. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Zhang, L.; Huang, J.; Lu, Y. A Quantitative Evaluation Study on Return-to-Hometown Entrepreneurship Policies in 16 Provinces (Municipalities) and Autonomous Regions in China under the Rural Revitalization Strategy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldpaus, L. Reconnecting the City: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach and the Future of Urban Heritage. Cult. Trends 2015, 24, 340–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, R. Setting the Scene: The Protection and Management of Cultural World Heritage Properties in a National Context. Hist. Environ.-Policy Pract. 2016, 7, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.B. Historical and Cultural Heritage Preservation in the United States and Its Comparison with the Development of Other Developed Countries. China Famous Cities 2011, 8, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.H. Policy and Planning for the Conservation of Urban Historical and Cultural Heritage. Urban Plan. 2004, 1, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Thatcher, M. Populism and Cultural Heritage Policies: Public Statues in Europe. J. Eur. Public Policy 2024, 32, 1122–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C. The Construction and Dismantling of the Pyongyang Folk Park: Changes in National Heritage Protection Policies during the Kim Jong-un Era. North Korean Stud. 2024, 49, 122–151. [Google Scholar]

- Foradori, P.; Rosa, P. Guardian of Culture: The European Union’s Quest for Actorness in the Protection of Cultural Heritage in Conflicts and Crises. Eur. Secur. 2025, 3, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabbar, U.N.; Yazgan, E.O. State Support Policy Concerning the Conservation of Traditional Architectural Heritage in Safranbolu, Turkey. Hist. Environ.-Policy Pract. 2016, 7, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.B.; Bian, L.C. The protection and sustainable development of cultural heritage: An example of cultural heritage registration systems in the UK, Japan and Korea. Sci. Technol. Her. 2019, 37, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H.H. Tax incentives in the field of cultural heritage preservation in the United States. J. Archit. 2006, 6, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- The Evolution of Built Heritage Conservation Policies in Saudi Arabia Between 1970 and 2015: The Case of Historic Jeddah-All Databases. Available online: https://webofscience.clarivate.cn/wos/alldb/full-record/PQDT:69029600 (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Owley, J. Cultural Heritage Conservation Easements: Heritage Protection with Property Law Tools. Land Use Policy 2015, 49, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekakis, S. Cultural Policy and Public Engagement with Modern Architectural Heritage in Greece: An Empirical Analysis. Cities 2025, 162, 105925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Dang, A.R.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.Y.; Yu, J.G. Research on the Protection and Inheritance of the Cultural Heritage of the Great Wall Based on Digital Twins. Chin. Gard. 2024, 40, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, B. Overall conservation management of the Great Wall of China: Challenges and explorations. China Cult. Herit. 2018, 3, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.L. Accelerating the Protection, Inheritance and Utilisation of the Great Wall Culture in Tianjin. Urban Dev. Res. 2023, 30, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Great Wall cultural fusion publishing and discourse dissemination of Chinese cultural values. Sci. Technol. Publ. 2022, 9, 120–128. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.F.; Zhang, C.Z.; Jiao, Q.Q.; Zhou, Z.Q.; Jiang, Q.Y.; Mao, R.H. A study on the construction of museums along the Great Wall and the dissemination of the culture of the Great Wall: The Great Wall Theme Museums. China Mus. 2024, 1, 6–15+130. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.; Shi, Y.N. Research on the interpretation and dissemination of cultural values of the Great Wall National Cultural Park. Hebei J. 2023, 43, 210–214. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, J. Evaluation of rural tourism development effect and development path selection along the linear cultural heritage protection zone—The Great Wall Cultural Belt in Beijing as an example. Urban Dev. Res. 2022, 29, 116–124. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, R.F.; Xu, C.C. Structural characteristics of the cultural and tourism resources of the Great Wall and strategies for enhancing the utilisation of tourism—The Hebei section of the Great Wall as an example. Hebei J. 2023, 43, 212–217. [Google Scholar]

- Spring, P. Great Wall and Linear Barrier; Pen and Sword: Barnsley, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Warnaby, G.; Medway, D.; Bennison, D. Notions of Materiality and Linearity: The Challenges of Marketing the Hadrian’s Wall Place “Product”. Environ. Plann. A Econ. Space 2010, 42, 1365–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, P. Assessing the Sustainable Development of the Historic Urban Landscape through Local Indicators. Lessons from a Mexican World Heritage City. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 46, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božić, S.; Tomić, N. Developing the Cultural Route Evaluation Model (CREM) and Its Application on the Trail of Roman Emperors, Serbia. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 17, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrelli, D.; Roberts, A.J. Exploring Digital Means to Engage Visitors with Roman Culture: Virtual Reality vs. Tangible Interaction. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2023, 16, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiver, J.; Lumsdon, L.; Weston, R. Traffic Reduction at Visitor Attractions: The Case of Hadrian’s Wall. J. Transp. Geogr. 2008, 16, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifu, I.C.; Ianchis, R.; Nistor, C.L.; Petcu, C.; Fierascu, I.; Fierascu, R.C. Polyelectrolyte Coatings-A Viable Approach for Cultural Heritage Protection. Materials 2023, 16, 2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Bo, W.; Yang, H.; Li, X. Deep Learning-Based Image Compression for Enhanced Hyperspectral Processing in the Protection of Stone Cultural Relics. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 271, 126691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.Q.; Xiong, H.X.; Du, J.; Shen, S.Y. Research on the safeguarding policy of intangible cultural heritage at the provincial level in China and its revelation: An analysis based on the three-dimensional framework of ‘tool-subject-goal’. Intell. Sci. 2023, 41, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell, R.; Zegveld, W. Reindustrialization and Technology; M.E. Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 1985; ISBN 978-0-87332-330-7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. Analysis of Zero-Waste City Policy in China: Based on Three-Dimensional Framework. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.H.; Gu, B.R.; Hong, B. The evolution of China’s public digital cultural service policy and the quantitative analysis of the text. Libr. J. 2024, 43, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, C.; Li, C.M.; Xu, J.T. A quantitative study of health information service policy for the elderly in China and its implications based on the three-dimensional analysis framework of ‘tool-goal-subject’. Mod. Intell. 2024, 44, 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Diligna, D.; Song, X.T. Quantitative evaluation of cultural heritage protection and innovation policies based on the PMC index model. J. Yunnan Univ. Natl. Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2023, 40, 52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.F.; Chen, W.L. Governance characteristics of China’s national park institutional development—A quantitative evaluation based on policy texts. Natl. Parks 2024, 2, 260–271, (In Chinese and English). [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.Y.; Xie, X.Y. Holistic protection of history and culture and its innovative development based on the logic of value chain. Adm. Reform 2024, 2, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, H.R.; Lu, Y.F. Triple reproduction: The internal mechanism of historical and cultural heritage in forging the sense of community of the Chinese nation. Ethn. Stud. 2025, 1, 13–27+142–143. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q.K.; Cheng, L. The return from “object-centered” to “people-centered”: New trends in international heritage scholarship. Southeast Cult. 2019, 2, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, H.B. Begins a New Phase of Great Wall Preservation. Guangming Daily, 2 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, W.; Zhong, Y. The Influence of Demand-Based Policy Instruments on Urban Innovation Quality-Evidence from 269 Cities in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).