Compassion Towards Nature and Well-Being: The Role of Climate Change Anxiety and Pro-Environmental Behaviors

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Connection to Nature, Mental Health, and Well-Being

1.2. Connection to Nature and Climate Change Anxiety

1.3. Climate Change Anxiety, Mental Health, and Well-Being

1.4. Climate Change Anxiety and Pro-Environmental Behavior

1.5. Pro-Environmental Behavior, Mental Health, and Well-Being

1.6. The Role of Compassion

1.7. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Participants

2.4. Measures

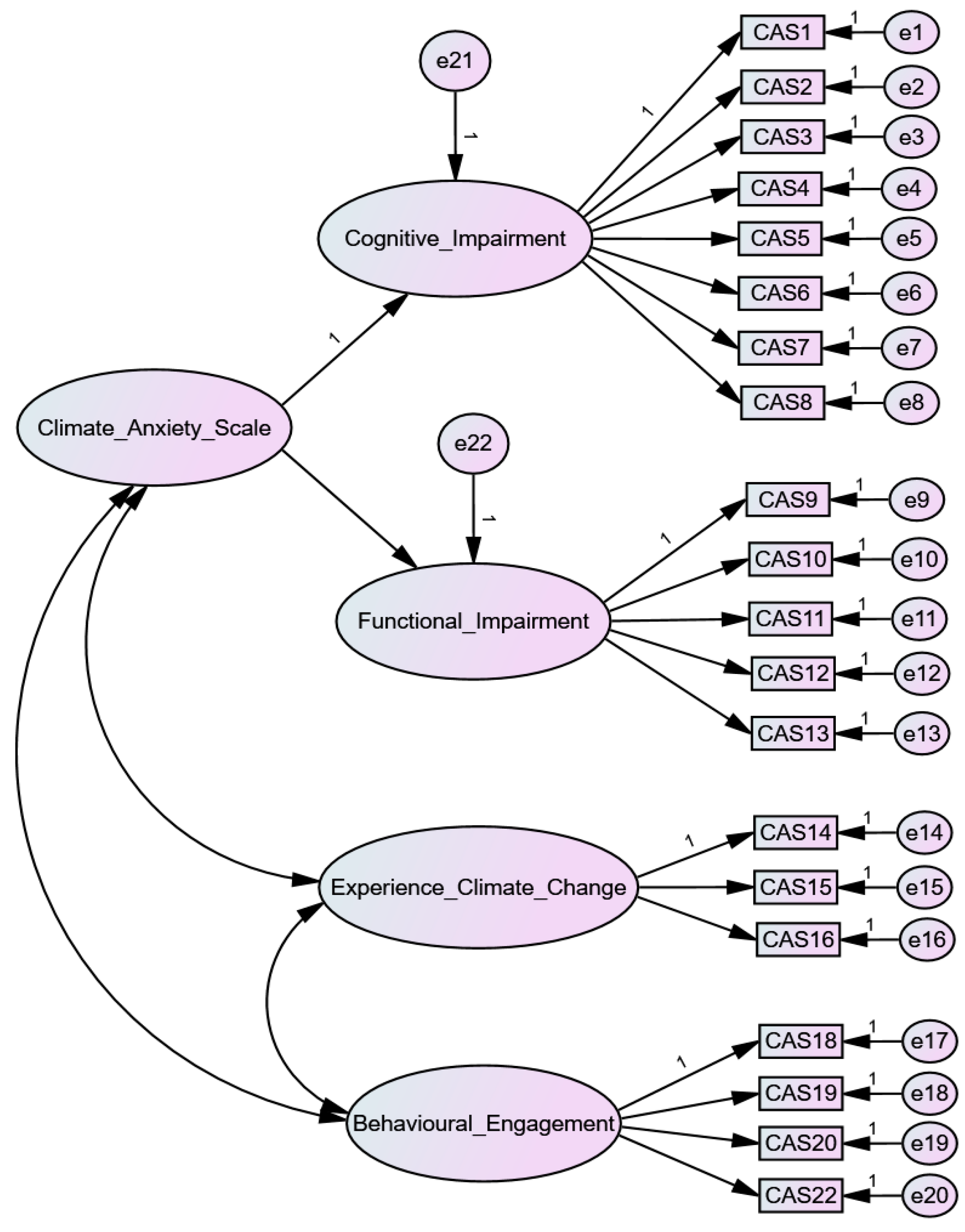

2.4.1. Climate Anxiety Scale (CAS) [39]

2.4.2. Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale (HEAS) [80,81]

2.4.3. Environmental Action Scale (EAS) [57,82]

2.4.4. Brief Version Connectedness to Nature Scale (CNS-Brief Version) [83,84]

2.4.5. Compassionate Engagement and Action Scales (CEAS) [85,86]

2.4.6. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS 21) [87,88]

2.4.7. PERMA-Profiler (PERMA) [89,90]

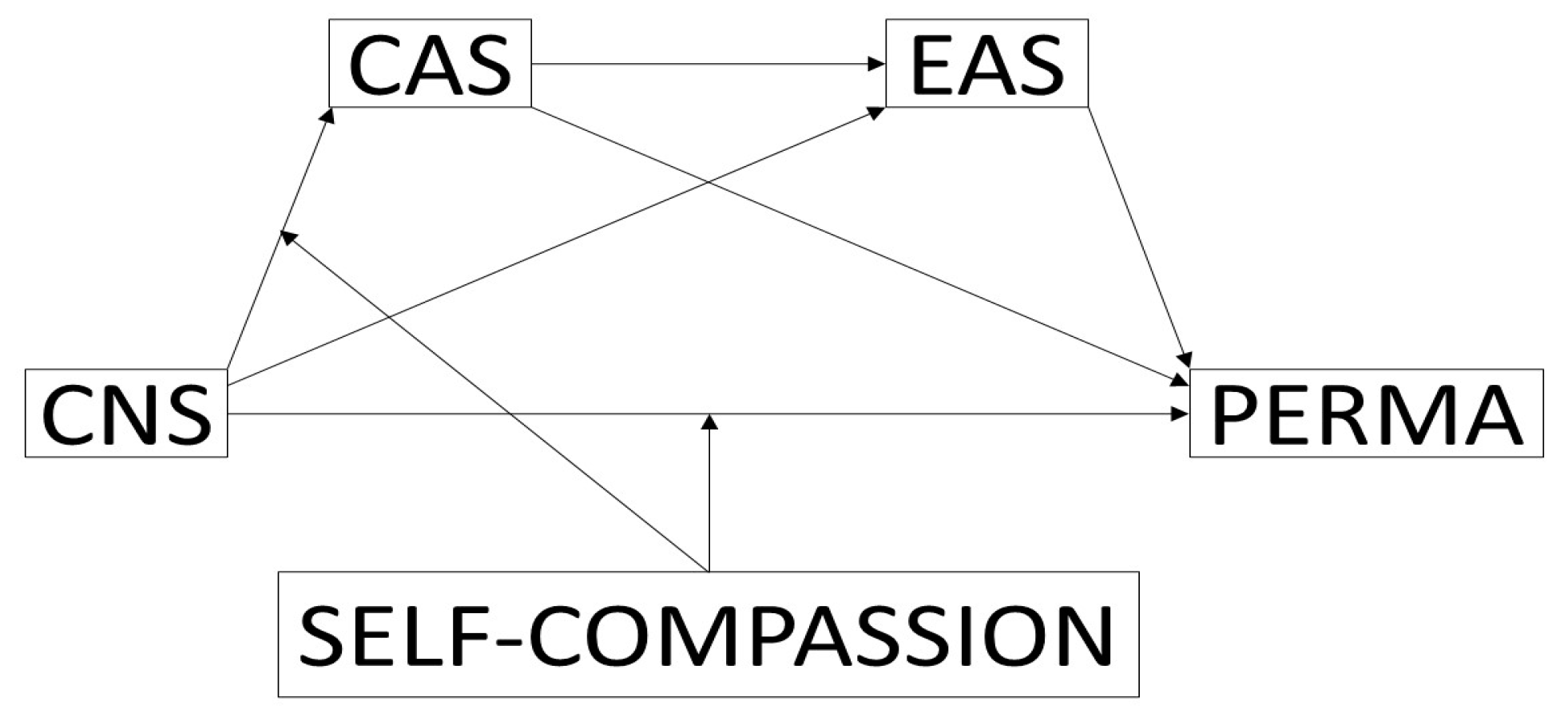

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Climate Change Anxiety Scale

3.1.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

3.1.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.1.3. Descriptive Statistics and Reliability

3.1.4. Convergent, Concurrent, and Divergent Validity

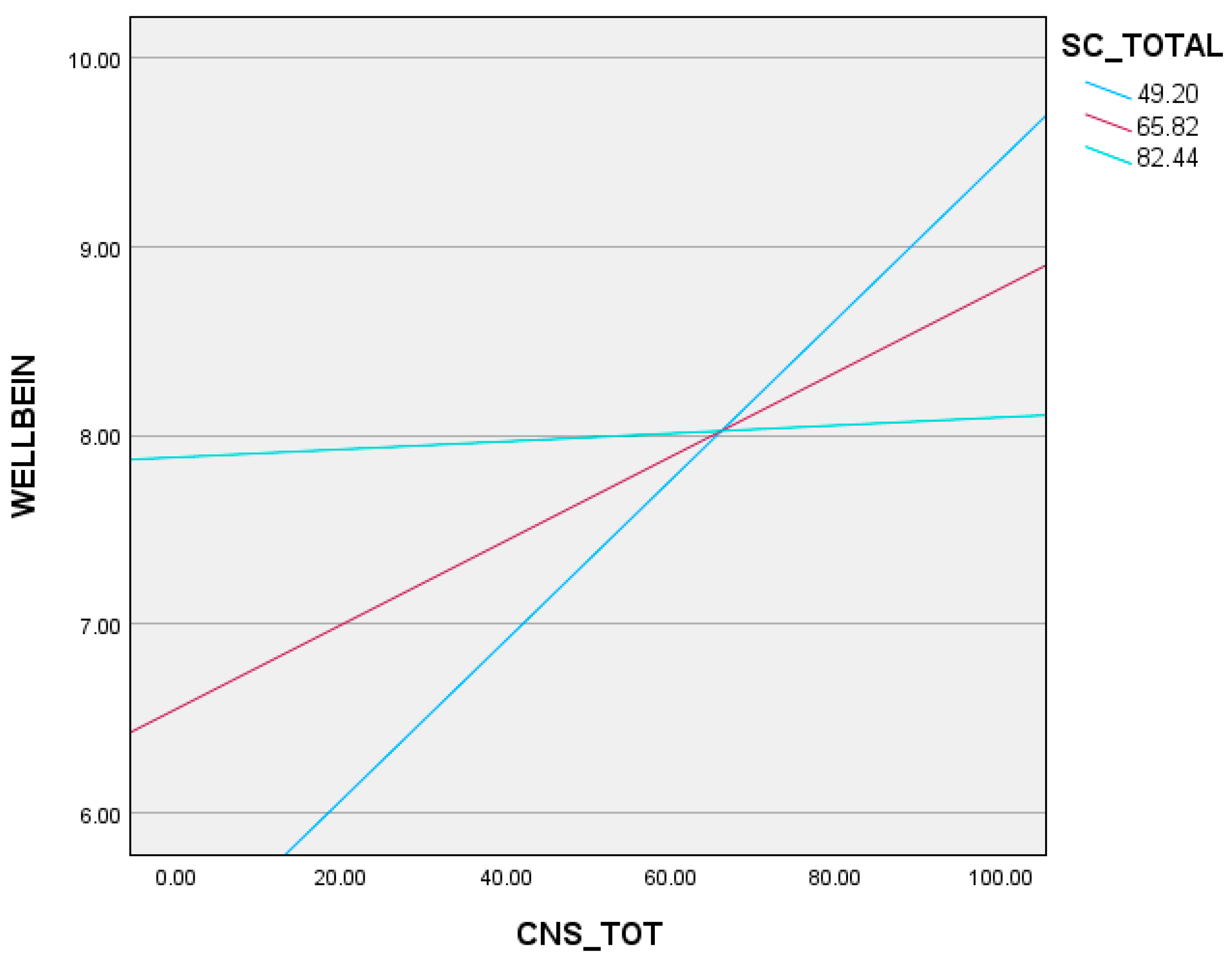

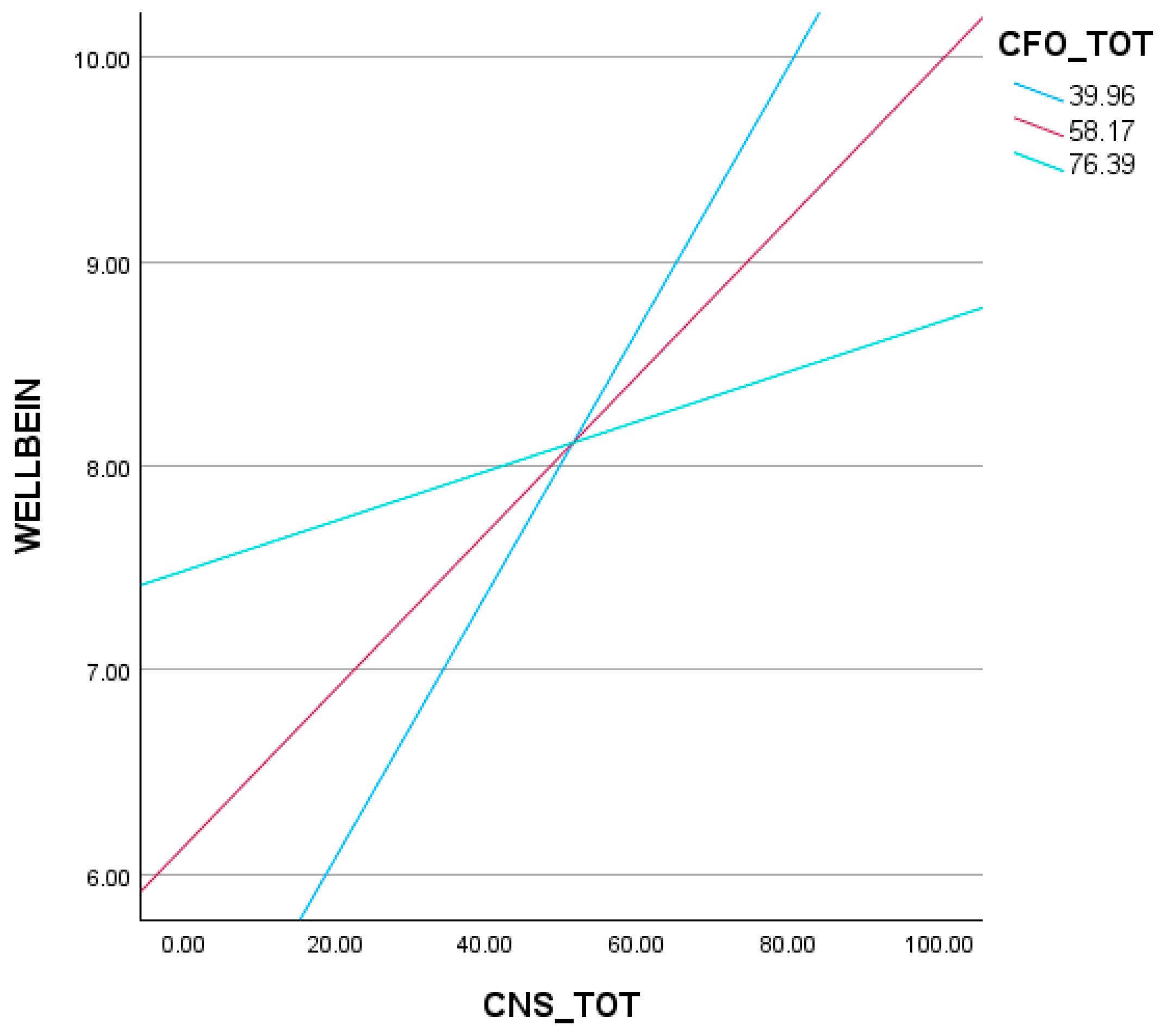

3.2. Moderated Mediation Model Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Connection to Nature and Climate Change Anxiety

4.2. Connection to Nature and Environmental Action

4.3. Connection to Nature and Well-Being

4.4. Climate Change Anxiety as a Mediator

4.5. Environmental Action as a Mediator

4.6. Self-Compassion and Receiving Compassion from Others as Moderators

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Sample 1 (n = 261) | Sample 2 (n = 261) | t/χ2 | d/V |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age M(SD) | 44.29 (11.82) | 44.65 (11.71) | −0.34 (520) | 0.03 |

| Gender n (%) Female | 187 (71.6) | 168 (67.47) | 3.97 | 0.09 |

| Residence n (%) Urban | 115 (44.06) | 113 (45.38) | 1.16 | 0.05 |

| Ethnia n (%) Caucasian | 214 (81.99) | 220 (88.35) | 10.64 | 0.14 |

| Education level n (%) Higher education | 165 (63.22) | 160 (64.26) | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| Marital status n (%) Married | 163 (62.45) | 148 (59.44) | 0.49 | 0.03 |

| Children n (%) Yes | 183 (70.11) | 159 (63.86) | 2.26 | 0.07 |

| Socioeconomic level n (%) Medium | 123 (47.13) | 117 (40.21) | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Physical health n (%) Good | 145 (55.56) | 115 (46.18) | 8.02 | 0.13 |

| Mental health n (%) Good | 131 (50.19) | 130 (52.21) | 2.25 | 0.07 |

| Psi/psi counseling n (%) No | 227 (86.97) | 216 (86.75) | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Contemplative practices n (%) No | 207 (79.30) | 190 (76.31) | 2.38 | 0.07 |

| Variables | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNS | 25.53 | 6.59 | −0.52 | −0.29 |

| Cognitive impairment | 11.80 | 4.45 | 1.78 | 3.94 |

| Functional impairment | 7.12 | 2.91 | 1.72 | 2.83 |

| CAS | 18.92 | 6.89 | 1.82 | 4.02 |

| Participatory action | 11.11 | 8.73 | 1.12 | 1.00 |

| Leadership action | 2.85 | 4.63 | 2.26 | 5.06 |

| Environmental action | 13.96 | 12.66 | 1.43 | 1.84 |

| Wellbeing | 7.08 | 1.69 | −1.10 | 2.04 |

| Self-compassion engagement | 37.58 | 9.99 | −0.52 | 0.59 |

| Self-compassion action | 28.24 | 8.31 | −0.60 | −0.13 |

| Self-compassion_total | 65.82 | 16.62 | −0.67 | 0.60 |

| Compassion from others engagement | 34.11 | 10.84 | −0.11 | −0.26 |

| Compassion from others action | 24.07 | 8.01 | −0.27 | −0.23 |

| Compassion from others_total | 58.17 | 18.22 | −0.19 | −0.25 |

| Items | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAS1 | 1.99 | 0.95 | 0.59 | −0.47 |

| CAS2 | 1.72 | 0.82 | 0.90 | 0.26 |

| CAS3 | 1.40 | 0.72 | 2.01 | 4.23 |

| CAS4 | 1.27 | 0.60 | 2.43 | 6.03 |

| CAS5 | 1.51 | 0.80 | 1.48 | 1.28 |

| CAS6 | 1.25 | 0.59 | 2.66 | 7.70 |

| CAS7 | 1.25 | 0.61 | 2.60 | 6.37 |

| CAS8 | 1.41 | 0.73 | 1.88 | 3.22 |

| CAS9 | 1.35 | 0.67 | 1.96 | 3.36 |

| CAS10 | 1.77 | 0.94 | 0.97 | −0.01 |

| CAS11 | 1.29 | 0.58 | 2.29 | 6.36 |

| CAS12 | 1.32 | 0.63 | 2.17 | 5.13 |

| CAS13 | 1.39 | 0.78 | 2.20 | 4.43 |

| CAS14 | 1.68 | 0.92 | 1.24 | 0.81 |

| CAS15 | 1.79 | 1.02 | 1.09 | 0.30 |

| CAS16 | 2.32 | 1.19 | 0.48 | −0.74 |

| CAS17 | 2.88 | 1.10 | −0.01 | −0.56 |

| CAS18 | 4.28 | 0.96 | −1.30 | 1.11 |

| CAS19 | 4.45 | 0.76 | −1.57 | 3.25 |

| CAS20 | 4.03 | 0.94 | −1.00 | 1.05 |

| CAS21 | 3.20 | 1.26 | −0.20 | −0.95 |

| CAS22 | 3.65 | 1.09 | −0.51 | −0.31 |

| F Test | Gender | Area | NSE | Etnia | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | M | F Test | η2 | R | SU | U | F Test | η2 | L | M | H | F Test | η2 | F Test | DF | p-Value | η2 | |

| Variable | M (SD) | M (SD) | M(SD) | M(SD) | M(SD) | M(SD) | M(SD) | M(SD) | ||||||||||

| CNS | 26.17 (6.40) | 24.02 (6.82) | 4.37 ** | 0.03 | 25.23 (6.45) | 27.88 (5.46) | 25.04 (6.90) | 5.74 ** | 0.02 | 25.27 (6.89 | 25.26 (6.70) | 26.56 (5.35) | 1.06 | 0.01 | 0.97 | 10.499 | 0.47 | 0.02 |

| CAS | 19.33 (7.32) | 17.99 (5.73) | 1.70 | 0.01 | 19.43 (7.66) | 19.25 (7.03) | 18.34 (6.05) | 1.48 | 0.01 | 20.46 (7.72) | 18.40 (6.58) | 18.39 (5.94) | 2.65 * | 0.02 | 2.08 | 10.499 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| EAS | 14.10 (12.32) | 13.57 (13.51) | 0.24 | 0.00 | 14.93 (12.88) | 15.03 (14.39) | 12.73 (11.77) | 1.96 | 0.01 | 14.45 (14.11) | 14.91 (13.57) | 11.37 (8.33) | 1.97 | 0.01 | 0.41 | 10.499 | 0.94 | 0.01 |

| WB | 7.09 (1.67) | 7.05 (1.71) | 1.53 | 0.01 | 7.20 (1.64) | 7.32 (1.59) | 6.89 (1.75) | 2.76 | 0.01 | 6.56 (1.78) | 7.20 (1.69) | 7.42 (1.32) | 5.60 *** | 0.03 | 0.76 | 10.499 | 0.67 | 0.02 |

| SC | 67.59 (15.92) | 61.79 (17.26) | 7.12 *** | 0.04 | 66.29 (16.38) | 67.09 (17.16) | 64.96 (16.69) | 0.60 | 0.00 | 64.42 (16.90) | 65.63 (17.49) | 68.27 (12.33) | 1.09 | 0.01 | 1.79 | 10.499 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| CFO | 59.20 (18.52) | 55.46 (17.27) | 2.40 | 0.01 | 57.54 (17.35) | 58.71 (18.44) | 58.57 (18.96) | 0.21 | 0.00 | 57.81 (18.29) | 57.48 (18.83) | 60.33 (15.44) | 0.62 | 0.00 | 0.39 | 10.499 | 0.95 | 0.01 |

| Correlation (r/rs) | CNS | CAS | EAS | WB | SC | CFO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education level a (r) | 0.08 | −0.10 * | 0.14 ** | 0.06 | 0.11 * | 0.11 * |

| Marital_Status b (r) | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.09 * | −0.09 * | −0.09 * |

| Children c (r) | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.15 ** |

| Psi/psi counseling d (r) | −0.09 | −0.06 | −0.07 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Contemplative practices e (r) | 0.21 ** | 0.08 | 0.14 ** | 0.06 | 0.10 * | 0.02 |

| Age (rs) | 0.17 ** | 0.10 * | 0.05 | 0.10 * | 0.01 | −0.12 ** |

| Physical health (rs) | −0.01 | −0.14 * | −0.01 | 0.27 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.11 * |

| Mental health (rs) | 0.01 | −0.19 ** | −0.07 | 0.39 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.15 ** |

References

- Clayton, S.; Manning, C.; Speiser, M.; Hill, A. Mental Health and Our Changing Climate: Impacts, Inequities, Responses; American Psychological Association, and ecoAmerica: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/mental-health-climate-change.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2024).

- IPCC. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report; Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 35–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Rouse, B.; Sarangi, P. Did Climate Change Influence the Emergence, Transmission, and Expression of the COVID-19 Pandemic? Front. Med. 2021, 8, 769208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, F.; Ali, S.; Benmarhnia, T.; Pearl, M.; Massazza, A.; Augustinavicius, J.; Scott, J.G. Climate Change and Mental Health: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Varghese, B.; Hansen, A.; Xiang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Dear, K.; Gourley, M.; Driscoll, T.; Morgan, G.; Capon, A.; et al. Is there an association between hot weather and poor mental health outcomes? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Int. 2021, 153, 106533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obradovich, N.; Migliorini, R.; Paulus, M.P.; Rahwan, I. Empirical evidence of mental health risks posed by climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 10953–10958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaglehole, B.; Mulder, R.; Frampton, C.; Boden, J.; Newton-Howes, G.; Bell, C. Psychological distress and psychiatric disorder after natural disasters: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 213, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Birthright: People and Nature in the Modern World; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2012; pp. 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1982, 52, 664–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachelard, G. The Poetics of Space; Orion Press, Inc.: Phoenix, AZ, USA, 1964; pp. 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- Fromm, E. The Heart of Man: Its Genius for Good and Evil, 2nd ed.; Harper & Row: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1980; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.R.; Wilson, E.O. The Biophilia hypothesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, J. The experience of landscape. Landsc. Res. 1975, 1, 15–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatersleben, B.; Andrews, M. When walking in nature is not restorative-the role of prospect and refuge. Health Place 2013, 20, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwan, K.; Giles, D.; Clarke, F.J.; Kotera, Y.; Evans, G.; Terebenina, O.; Minou, L.; Teeling, C.; Basran, J.; Wood, W.; et al. A Pragmatic Controlled Trial of Forest Bathing Compared with Compassionate Mind Training in the UK: Impacts on Self-Reported Wellbeing and Heart Rate Variability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwan, K.; Potter, V.; Kotera, Y.; Jackson, J.E.; Greaves, S. ‘This Is What the Colour Green Smells Like!’: Urban Forest Bathing Improved Adolescent Nature Connection and Wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M. The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, J.L.; Benassi, V.A. The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of emotional connection to nature? J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.L.; Green, J.D.; Reed, A. Interdependence with the environment: Commitment, interconnectedness, and environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Environmental Identity: A Conceptual and an Operational Definition. In Identity and the Natural environment: The Psychological Significance of Nature; Clayton, S., Opotow, S., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.P. Concepts and measures related to connection to nature: Similarities and differences. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, C.M.L.; Schmitt, M.T. Do people who feel connected to nature do more to protect it? A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 65, 101323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission Directorate-General for Communication (2023). Special Eurobarometer 538 Climate Change. In Special Eurobarometer 538 Climate Change-Report; Directorate-General for Climate Action (European Commission), Ed.; Directorate-General for Communication: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, A.; Poortinga, W.; Pidgeon, N. The psychological distance of climate change. Risk Anal. 2012, 32, 957–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennerley, H.; Kirk, J.; Westbrook, D. An Introduction to Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- van der Linden, S. The social-psychological determinants of climate change risk perceptions: Towards a comprehensive model. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 41, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damásio, A. O Erro de Descartes, Emoção, Razão e Cérebro Humano; Temas e Debates: Lisboa, Portugal, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Swim, J.K.; Stern, P.C.; Doherty, T.J.; Clayton, S.; Reser, J.P.; Weber, E.U.; Gifford, R.; Howard, G.S. Psychology’s contributions to understanding and addressing global climate change. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. Empathizing with nature: The effects of perspective taking on concern for environmental issues. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Kalof, L. Value orientations, gender, and environmental concern. Environ. Behav. 1993, 25, 322–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, S. Determinants and measurements of climate change risk perception, worry, and concern. In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Climate Change Communication; Nisbet, M.C., Schafer, M., Markowitz, E., Ho, S., O’Neill, S., Thaker, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.S.; Liese, B.S.; Najavits, L.M. Cognitive Therapy. In Clinical Textbook of Addictive Disorders, 3rd ed.; Frances, R.J., Miller, S.I., Mack, A.H., Eds.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 474–501. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, D.H. Anxiety and Its Disorders: The Nature and Treatment of Anxiety and Panic, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, S.; Karazsia, B.T. Development and validation of a measure of climate change anxiety. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 69, 101434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.; González, F.; Baylis, P.; Heft-Neal, S.; Baysan, C.; Basu, S.; Hsiang, S. Higher temperatures increase suicide rates in the United States and Mexico. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nori-Sarma, A.; Sun, S.; Sun, Y.; Spangler, K.R.; Oblath, R.; Galea, S.; Gradus, J.L.; Wellenius, G.A. Association between ambient heat and risk of emergency department visits for mental health among US adults, 2010 to 2019. JAMA Psychiatry 2022, 79, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, H.L.; Bowen, K.; Kjellstrom, T. Climate change and mental health: A causal pathways framework. Int. J. Public Health 2010, 55, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, N.R.; Albrecht, G.A. Climate change threats to family farmers’ sense of place and mental wellbeing: A case study from the Western Australian Wheatbelt. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 175, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Marks, E.; Dobromir, A.I. On the nature of eco-anxiety: How constructive or unconstructive is habitual worry about global warming? J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 72, 101528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.E.O.; Benoit, L.; Clayton, S.; Parnes, M.F.; Swenson, L.; Lowe, S.R. Climate change anxiety and mental health: Environmental activism as buffer. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 42, 16708–16721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behaviour? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L. Significant life experiences revisited: A review of research on sources of environmental sensitivity. J. Environ. Educ. 1998, 29, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, S.V.; Pollitt, A.; Barnett, M.A.; Curran, M.A.; Craig, Z.R. Differentiating environmental concern in the context of psychological adaption to climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 2018, 48, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, G.L.; Babutsidze, Z.; Chai, A.; Reser, J.P. The role of climate change risk perception, response efficacy, and psychological adaptation in pro-environmental behavior: A two nation study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 68, 101410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; de Groot, J. Environmental Psychology: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleres, J.; Wettergren, A. Fear, hope, anger, and guilt in climate activism. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2017, 16, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, S.; Hogg, T.; Leviston, Z.; Walker, I. From anger to action: Differential impacts of eco-anxiety, eco-depression, and eco-anger on climate action and well-being. J. Clim. Change Health 2021, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAngelo, L.; Schuster, M.T.; Stebleton, M.J. California DREAMers: Activism, identity, and empowerment among undocumented college students. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2016, 9, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral-Verdugo, V.; Durón, F.; Frías, M.; Tapia, C.O.; Fraijo, B.; Gaxiola, J. Socio-physical environmental factors and sustainable behaviour as indicators of family positivity. PsyEcol. Biling. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 6, 146–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Climate Change and Mental Health. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2021, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albright, J.N.; Hurd, N.M. Activism, social support, and trump-related distress: Exploring associations with mental health. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2023, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alisat, S.; Riemer, M. The environmental action scale: Development and psychometric evaluation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, C.A.; Cumsille, P.; Gill, S.; Gallay, L.S. Sense of Community Connectedness Scale [Database Record]; APA PsycTests: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehnke, K.; Wong, B. Adolescent political activism and long-term happiness: A 21-year longitudinal study on the development of micro- and macrosocial worries. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 37, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, P. The evolution and social dynamics of compassion. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2015, 9, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. Compassion: Conceptualisations, Research and Use in Psychotherapy; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. The Compassionate Mind: A new Approach to the Challenge of Life; Constable & Robinson: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. Compassion Focused Therapy: The CBT Distinctive Features Series; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelo, N.; White, K.; Goode, M.R. Nature promotes self-transcendence and prosocial behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 76, 101639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelenski, J.M.; Dopko, R.L.; Capaldi, C.A. Cooperation is in our nature: Nature exposure may promote cooperative and environmentally sustainable behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellar, J.E.; Gordon, A.M.; Piff, P.K.; Cordaro, D.; Anderson, C.L.; Bai, Y.; Maruskin, L.A.; Keltner, D. Self-transcendent emotions and their social functions: Compassion, gratitude, and awe bind us to others through prosociality. Emot. Rev. 2017, 9, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Cunnington, R.; Kirby, J.N. The neurophysiological basis of compassion: An fMRI meta-analysis of compassion and its related neural processes. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 108, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrow, M.R.; Washburn, K. A Review of Field Experiments on the Effect of Forest Bathing on Anxiety and Heart Rate Variability. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2019, 8, 2164956119848654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, J.N.; Tellegen, C.L.; Steindl, S.R. A Meta-Analysis of Compassion-Based Interventions: Current State of Knowledge and Future Directions. Behav. Ther. 2017, 48, 778–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, T.; Elliott, E. Beliefs, attitudes and intentions towards environmental issues: The role of self-compassion and wellbeing. J. Psychol. Clin. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.; Germer, C. Self-compassion and psychological well-being. In The Oxford Handbook of Compassion Science; Seppälä, E.M., Simon-Thomas, E., Brown, S.L., Worline, M.C., Cameron, C.D., Doty, J.R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 371–385. [Google Scholar]

- Manneh, A. A mind, brain, health and education approach to nature-induced compassion: Assessment of the potential of exposure to nature as a protective factor to induce nondual compassion in adults. ResearchGate 2021, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenberg, P.L.A.; Vago, D.R. Mapping meditative states and stages with electrophysiology: Concepts, classifications, and methods. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 28, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josipovic, Z. Neural correlates of nondual awareness in meditation. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2014, 1307, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josipovic, Z. Love and compassion meditation: A nondual perspective. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2016, 1373, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperatori, C.; Massullo, C.; De Rossi, E.; Carbone, G.A.; Theodorou, A.; Scopelliti, M.; Romano, L.; Del Gatto, C.; Allegrini, G.; Carrus, G.; et al. Exposure to nature is associated with decreased functional connectivity within the distress network: A resting state EEG study. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1171215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crutzen, P.J.; Stoermer, E.F. The ‘Anthropocene’ (2000). In Paul J. Crutzen and the Anthropocene: A New Epoch in Earth’s History; Benner, S., Lax, G., Crutzen, P.J., Pöschl, U., Lelieveld, J., Brauch, H.G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 19–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galway, L.P.; Beery, T. Exploring climate emotions in Canada’s provincial north. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 920313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. Evolution, Compassion, and Wellbeing. In Toward an Integrated Science of Wellbeing; Rieger, E., Costanza, R., Kubiszewski, I., Dugdale, P., Eds.; Oxford Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2023; pp. 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, T.L.; Stanley, S.K.; O’Brien, L.V.; Wilson, M.S.; Watsford, C.R. The Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale: Development and validation of a multidimensional scale. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 71, 102391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, F.; Costa, T.; Teixeira-Santos, L.; de Pinho, L.G.; Sequeira, C.; Luís, S.; Loureiro, A.; Soro, J.C.; Roldán Merino, J.; Moreno Poyato, A.; et al. Validating a measure for eco-anxiety in Portuguese young adults and exploring its associations with environmental action. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona, B.; Loureiro, A.; Aguilar-Luzón, M.C. Environmental Action Scale: Psychometric properties of the Portuguese version (Escala de Acciones Ambientales: Propiedades psicométricas de la versión portuguesa). Psyecology 2021, 12, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasca, L.; Aragonés, J.I.; Coello, M.T. An analysis of the connectedness to nature scale based on item response theory. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, A.; Olivos, P. The role of environmental values, environmental identity, and contact with nature, in predicting support for pro-environmental behaviours. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Environmental Psychology, A Coruña, Spain, 30 August–1 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P.; Catarino, F.; Duarte, C.; Matos, M.; Kolts, R.; Stubbs, J.; Ceresatto, L.; Duarte, J.; Pinto-Gouveia, J.; Basran, J. The development of compassionate engagement and action scales for self and others. J. Compassionate Health Care 2017, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, M.; Duarte, C.; Pinto-Gouveia, J. Constructing a self-protected against shame: The importance of warmth and safeness memories and feelings on the association between shame memories and depression. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 2015, 15, 317–335. [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The Structure of Negative Emotional States: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pais-Ribeiro, J.L.; Honrado, A.; Leal, I. Contribuição para o Estudo da Adaptação Portuguesa das Escalas de Ansiedade, Depressão e Stress de Lovibond e Lovibond. Psicol. Saúde Doenças 2004, 36, 229–239. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J.; Kern, M.L. The PERMA-Profiler: A brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. Int. J. Wellbeing 2016, 6, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.; Lourenço, M.; Brito, A.; Gouveia, M. Confirmação da estrutura fatorial da versão portuguesa do questionário de Florescimento Psicológico—PERMA-Profiler 2016. In Proceedings of the 3º Congresso da Ordem dos Psicólogos Portugueses, Porto, Portugal, 28 September–1 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle, J. Amos; (Version 27.0); [Computer Program]; IBM: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modelling, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 5th ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. Using SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 4th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 3rd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kutner, M.; Nachtsheim, C.; Neter, J.; Li, W. Applied Linear Statistical Models, 5th ed; McGraw-Hill: Irwin, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriazos, T.; Poga, M. Dealing with multicollinearity in factor analysis: The problem, detections, and solutions. Open J. Stat. 2023, 13, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouguiama-Daouda, C.; Blanchard, M.; Coussement, C.; Heeren, A. On the Measurement of Climate Change Anxiety: French Validation of the Climate Anxiety Scale. Psychol. Belg. 2022, 62, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, S.; High, A. Psychometric properties of the Climate Change Anxiety Scale. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 84, 101905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innocenti, M.; Santarelli, G.; Vanessa Faggi, V.; Castellini, G.; Manelli, I.; Magrini, G.; Galassi, F.; Ricca, V. Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Climate Change Anxiety Scale. J. Clim. Change Health 2021, 3, 2667–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larionow, P.; Sołtys, M.; Izdebski, P.; Mudło-Głagolska, K.; Golonka, J.; Demski, M.; Rosińska, M. Climate Change Anxiety assessment: The psychometric properties of the Polish version of the Climate Anxiety Scale. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 870392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.; Strosahl, K.; Wilson, K. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, M.; Albuquerque, I.; Galhardo, A.; Cunha, M.; Pedroso Lima, M.; Palmeira, L.; Petrocchi, N.; McEwan, K.; Maratos, F.A.; Gilbert, P. Nurturing compassion in schools: A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of a Compassionate Mind Training program for teachers. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godinho, A.; Schell, C.; Cunningham, J.A. Out damn bot, out: Recruiting real people into substance use studies on the internet. Subst. Abus. 2020, 41, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Items | FACTOR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| CAS1 | 0.69 | ||||

| CAS2 | 0.76 | ||||

| CAS3 | 0.75 | ||||

| CAS4 | 0.79 | ||||

| CAS5 | 0.80 | ||||

| CAS6 | 0.78 | ||||

| CAS7 | 0.67 | ||||

| CAS8 | 0.78 | ||||

| CAS9 | 0.79 | ||||

| CAS10 | 0.78 | ||||

| CAS11 | 0.80 | ||||

| CAS12 | 0.78 | ||||

| CAS13 | 0.56 | ||||

| CAS14 | −0.85 | ||||

| CAS15 | −0.87 | ||||

| CAS16 | −0.80 | ||||

| CAS17 a | −0.69 | ||||

| CAS18 | 0.79 | ||||

| CAS19 | 0.70 | ||||

| CAS20 | 0.84 | ||||

| CAS21 a | −0.65 | ||||

| CAS22 | 0.60 | ||||

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.89 | 0.72 | 0.80 | 0.53 | 0.83 |

| Scale | M (SD) | Range | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|

| Climate Anxiety Scale | 18.92 (6.89) | 13–55 | 0.92 |

| Cognitive impairment | 11.80 (4.45) | 8–35 | 0.89 |

| Functional Impairment | 7.12 (2.91) | 5–20 | 0.86 |

| Experience with climate change | 5.78 (2.64) | 3–15 | 0.79 |

| Engagement behaviour | 16.41 (2.74) | 4–20 | 0.70 |

| HEAS | 5.33 (6.18) | 0–34 | 0.94 |

| EAS | 13.96 (12.66) | 0–62 | 0.93 |

| CNS | 25.59 (6.56) | 7–35 | 0.89 |

| CEAS-SC | 65.98 (16.55) | 10–100 | 0.90 |

| CEAS-CFO | 58.20 (18.13) | 10–100 | 0.96 |

| Well-Being (PERMA) | 7.08 (1.69) | 0–10 | 0.96 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAS | 1 | ||||||||||

| Cognitive impairment | 0.96 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| Functional Impairment | 0.90 ** | 0.74 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| Experience with Climate Change | 0.46 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.44 ** | 1 | |||||||

| Behavioral Engagement | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.10 * | 0.18 ** | 1 | ||||||

| HEAS | 0.74 ** | 0.68 ** | 0.70 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.09 | 1 | |||||

| EAS | 0.32 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.36 ** | 1 | ||||

| CNS | 0.15 ** | 0.13 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.35 ** | 1 | |||

| CEAS-SC | −0.09 * | −0.08 | −0.09 | 0.04 | 0.19 ** | −0.11 * | 0.10 ** | 0.29 ** | 1 | ||

| CEAS-CFO | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.05 | 0.12 ** | 0.19 ** | −0.03 | 0.08 | 0.20 ** | 0.46 ** | 1 | |

| Well-Being (PERMA) | −0.19 ** | −0.17 ** | −0.19 ** | 0.03 | 0.18 ** | −0.19 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.56 ** | 0.45 ** | 1 |

| DASS-21 | 0.35 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.18 ** | −0.05 | 0.46 ** | 0.08 | 0.07 | −0.17 ** | −0.09 * | −0.37 ** |

| Effect | Path | Unstandardized Coefficient | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Direct | CNS -> WB | 0.100 *** | 0.042 | 0.162 |

| Direct | CNS -> WB|Self-compassion = −1 SD | 0.040 *** | 0.019 | 0.066 |

| Direct | CNS -> WB|Self-compassion = 0 SD | 0.020 * | 0.002 | 0.042 |

| Direct | CNS -> WB|Self-compassion = +1 SD | 0.002 | −0.023 | 0.028 |

| Indirect | CNS -> CAS -> WB | −0.009 | −0.016 | −0.004 |

| Indirect | CNS -> EAS -> WB | 0.010 | 0.003 | 0.016 |

| Indirect | CNS -> CAS -> EAS -> WB | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.003 |

| Effect | Path | Unstandardized Coefficient | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Direct | CNS -> WB | 0.123 *** | 0.067 | 0.178 |

| Direct | CNS -> WB |Compassion from others = −1 SD | 0.065 *** | 0.040 | 0.090 |

| Direct | CNS -> WB |Compassion from others = 0 SD | 0.039 *** | 0.018 | 0.059 |

| Direct | CNS -> WB |Compassion from others = +1 SD | 0.012 | −0.016 | 0.040 |

| Indirect | CNS -> CAS -> WB | −0.009 | −0.016 | −0.004 |

| Indirect | CNS -> EAS -> WB | 0.010 | 0.004 | 0.016 |

| Indirect | CNS -> CAS -> EAS -> WB | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prata, A.; Matos, M. Compassion Towards Nature and Well-Being: The Role of Climate Change Anxiety and Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104349

Prata A, Matos M. Compassion Towards Nature and Well-Being: The Role of Climate Change Anxiety and Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104349

Chicago/Turabian StylePrata, Armando, and Marcela Matos. 2025. "Compassion Towards Nature and Well-Being: The Role of Climate Change Anxiety and Pro-Environmental Behaviors" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104349

APA StylePrata, A., & Matos, M. (2025). Compassion Towards Nature and Well-Being: The Role of Climate Change Anxiety and Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Sustainability, 17(10), 4349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104349