Abstract

Transitioning to sustainable systems often faces significant challenges. People from different backgrounds often have different views on sustainability, which may lead to group polarisation. To promote collective participation in the transition to sustainability, it is critical to understand the drivers of polarisation and promote inclusiveness in decision-making. We developed a Dialogue Tool based on the HUMAT framework to explore opinion dynamics such as polarisation in the community and find potential pathways to reconcile when division occurs. By simulating dissatisfaction, division, and reconciliation in the community, we studied how individual characteristics (such as openness to change and assertiveness) affect collective decisions. Furthermore, the Dialogue Tool can be used to test possible interventions to reduce polarisation and increase community satisfaction. Visual representations of community dynamics under different scenarios within the Dialogue Tool have the potential to foster meaningful dialogues among stakeholders, which may promote a deeper reflection on community collaboration. While limitations such as simplifications and lack of empirical calibration limit the predictive accuracy of the Dialogue Tool (although this is not its goal), it still shows strong potential for educational and policy applications. It offers insights into social influences, conformity, and polarisation in community settings, making it a promising tool for fostering inclusive, informed decision-making and strengthening community participation in sustainable development transitions.

1. Introduction

As the pace of global efforts to promote sustainable development accelerates, it becomes more clear that, although individual efforts are valuable, their role alone in achieving large-scale sustainable development is quite limited. The transition to sustainable development relies heavily on collective efforts. Communities are key players in this sustainable transition because collective action and resource sharing are the foundation for large-scale change [1]. Initiatives such as car sharing, improving cycling infrastructure, reducing urban traffic, and community-led heating systems are environmentally friendly alternatives that can not only improve energy efficiency and reduce emissions, but also make our living environment more comfortable and healthier. It is worth noting that the success of these initiatives depends on collective efforts, which can also highlight the indispensable role of communities in achieving the SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals, https://sdgs.un.org/goals, accessed on 1 May 2024).

In fact, communities often encounter challenges when promoting sustainable development [2]. First and foremost, people often resist change because they are unwilling to change their long-established living habits [3]. Next, people have different understandings of sustainable development, and this disagreement can lead to internal conflicts within the community. To complicate matters, social issues such as inequality in education and income and job instability can further deepen this conflict, making it particularly difficult to reach a consensus [4]. Furthermore, the long-term impacts of initiatives or changes are uncertain, often requiring communities to find a balance between meeting short-term needs and pursuing long-term environmental goals, which can be very challenging. Combined, these challenges often make communities hesitant about whether to adopt sustainable practices. To resolve this hesitation, it is key to listen to the opinions from different groups and promote public engagement [5]. This way, sustainable solutions can gain the support of the majority.

Agent-based modelling (ABM) emerges as a powerful tool for studying how communities interact and evolve. By modelling individual behaviours and mutual influence between individuals, ABM helps explain collective decision-making phenomena such as polarisation [6,7]. Recent research shows that ABMs can not only track the formation of group opinions but also analyse how opposing information deepens differences between groups [8]. More importantly, it is particularly useful in dealing with social complexity. For example, it can simulate how conformity pressure silences disadvantaged groups, while also showing how minority views and new information shape decisions [9]. Further studies on conformity and resistance to it (anti-conformity) reveal how these forces can divide society and increase the difficulty of democratic decision-making [10]. When promoting sustainable development, understanding these social dynamics is particularly critical to formulating policies that foster inclusivity and social cohesion.

However, despite the rich theoretical results, how to apply these findings to community practice remains a challenge. Agent-based models (ABMs) offer an ideal solution—they are like virtual laboratories where various scenarios can be tested without real-world risks, and they also allow stakeholders to engage in participatory simulations (e.g., using platforms such as Cormas) [11,12,13]. This approach can promote dialogue and communication among stakeholders. Practical applications have shown that ABMs have two advantages: first, it can intuitively display complex social dynamics; second, it can assess the potential impact of policy implementation [11,14], thereby supporting more informed and collaborative decisions. With the development of technology, current ABMs can restore more realistic community scenarios, including large-scale group behaviour (thousands of people) and complex policy impact analysis [15].

ABM has been widely used in social ecological systems, public governance, and sustainable community construction [16,17]. For example, in urban research, ABM has been used to analyse community energy systems and mobility patterns, where the platform NetLogo has been widely used due to its ease of use [18]. Systematic reviews further emphasise that ABM has unique advantages in analysing social–ecological interactions and can offer critical insights for policy making [16]. Although ABM has made significant progress in both theory and practice, its application in the community democracy process is still lagging behind, mainly due to the technical threshold of modelling and the difficulty of converting case data into models. In this study, we aim to develop an ABM tool that allows non-modellers to implement some key characteristics of community issues in a stylised ABM, and simulate social dynamics that support dialogues on community issues.

This “Dialogue Tool”, as we call it, is designed to promote dialogues and inclusive decision-making within communities [19]. The platform we use is NetLogo, one of the most suitable and user-friendly ABM platforms [20], allowing for running simulations online without local installation. By simulating interactions between different individuals and groups, and visualising the results of these interactions, the Dialogue Tool can facilitate open dialogues between individuals. By enabling them to understand how individual decisions affect others as well as the dynamics and the collective outcomes of the community, the tool may promote empathy and shared understanding within the community.

We use the term “Gaming polarisation” rather than “Simulating polarisation” as the title because the purpose of the tool is not to simulate existing cases of community projects in a very realistic manner, but rather to provide a stylised game-like experience to understand the social dynamics and consequences of certain scenarios, thereby raising awareness and facilitating discussions among different stakeholders on their case. Moreover, gaming is also associated with a fun activity, and we want to emphasise that exploring the social dynamics in communities can be a very playful activity.

Through this novel application of ABM, our research aims to (1) uncover the deep causes of social polarisation, (2) assess its impact on social cohesion, and (3) explore strategies to enhance the inclusiveness of democratic deliberation. This exploration will not only expand the research boundaries of computational social science, but also make meaningful contributions to the theory and practice of building sustainable community governance.

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Role of Democracy in Sustainability

Democracy is the key to promoting the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals. Studies have shown that democracy can directly affect the speed of development in various areas, like institutions, society, economy, and public awareness [21]. One way to improve the quality of democracy is through democratic innovation (DI), a governance approach that allows the public to participate more deeply in decision-making through new forms, such as citizen assemblies and participatory budgeting [22]. This not only gives citizens the right to speak, but also promotes social dialogue and overall society harmony [23].

Traditional governance models are often unable to cope with the challenges of sustainable development. Their top-down, rigid hierarchical structures often fail to adapt or include diverse voices, making it difficult to address complex social and ecological issues [24]. In contrast, democratic innovations absorb the opinions of different groups by establishing a flexible decision-making mechanism [25].

The key to promoting sustainable development lies in the integration of democracy and sustainability efforts. This requires the establishment of an inclusive participation platform to create a space for stakeholders to collaborate, so that they can share their concerns and develop solutions that meet local actual needs and reflect group values.

2.2. Applying ABM to Enhance Participation in the Democratic Process

Although participatory modelling (PM) shares similarities with democratic innovation (DI) in encouraging stakeholder involvement, they have different focuses [26]: DI works on improving participation in governance, while PM focuses on multi-party collaborative modelling [27,28]. In PM practice, stakeholders like community leaders and policymakers collaborate to develop interactive tools to integrate scientific research and local expertise to deepen the understanding of social environmental systems.

Among various PM approaches, agent-based modelling (ABM) stands out [29]. Its core value is reflected in (a) intuitively visualising complex social dynamics and evaluating the impact of different policy interventions, and (b) providing an interactive tool where community members can explore different scenarios together [30]. This can not only enhance people’s common understanding of the challenges and opportunities in democratic systems, but also promote more informed collective decision-making by revealing the relationship between individual behaviour and social dynamics.

To bridge the understanding gap among multiple stakeholders, we attempt to combine DIs with ABM to develop a collaborative platform. This platform connects scientific theories with field experiences in two ways: On the one hand, it uses its scenario simulation capabilities to raise people’s awareness of polarisation and use it as a link to promote meaningful dialogues between groups [31]. On the other hand, it provides policymakers with a testing tool and researchers with methods to study social dynamics [16].

2.3. HUMAT as an Architecture of the Dialogue Tool

As explained above, we are devoted to developing a collaborative platform called Dialogue Tool to help different groups communicate better. The core of this tool is the HUMAT framework, which is an architecture for modelling social dynamics using agent-based models [32]. HUMAT is based on scientific theory and combines the complexity of individual cognition and social interaction. It can be used to simulate social phenomena such as social innovation and behavioural transitions.

In the HUMAT framework, agents interact in dynamic social networks. Their decisions are shaped by personal experiences and values, information dissemination, and prevailing social norms [33]. An agent’s activity in this framework begins with his or her satisfaction or dissatisfaction with various behavioural alternatives. These alternatives vary in how well they satisfy the agent’s needs (experiential, social, and values). Differential satisfaction between different sets of needs may cause agents experiencing cognitive dissonance, which affects how they process information and what they do next [34].

When the agent evaluates available alternatives, it tends to choose the most satisfying alternative. When alternatives are similar in satisfaction, considers the alternative that causes the least cognitive dissonance, that is, the agent tends to choose the alternative that requires the least effort to mitigate the dissonance. Continuous cognitive dissonance drives the agent to explore its social network, seeking more information to resolve the dissonance or find better alternatives. In the context of opinion dynamics, agents having cognitive dissonance may adopt two strategies to relieve this tension: they may attempt to persuade connected agents to adopt their viewpoints (signalling), or they may search information from connected agents to uphold their opinions (inquiring). Agents maintain cognitive representations of past evaluations of potential alternatives, resulting in a dynamic individual ranking of these alternatives. The evolution of the memory stack of agents is influenced by experienced satisfaction, the addition of new outcomes, and the current focal need [32].

The HUMAT framework was first developed under the SMARTEES (https://local-social-innovation.eu, accessed on 1 May 2024) project, which aims to examine the dynamics of transition through local social innovations. So far, HUMAT has been and is being implemented through various case studies and practical applications, demonstrating its effectiveness in modelling complex social dynamics [35].

2.4. Individual Opinion and Group Categorisation

To understand collective behaviour that influences community decision-making and democratic processes, we focus on two core mechanisms: group categorisation and the evolution of individual opinions.

Group categorisation is rooted in social identity theory, which involves people classifying themselves and others into different social groups based on common characteristics (e.g., education, friends and relatives, interests, etc.) [36]. This process essentially constructs social cognition by dividing the boundaries between “us” (in-group) and “them” (out-group). It is worth noting that this categorisation often strengthens the identification of “insiders” and the exclusion of “outsiders”, which may cause cognitive bias and even social confrontation within the community [37].

The evolution of individual opinions explores how personal attitudes shift over time. We focus on two key factors: the social influence on individuals and individual self-assertiveness. Social influence plays a central role in opinion dynamics. The theory argues that individuals adjust their opinions through persuasion, compliance, and seeking similarity with peers [38]. In contrast, self-assertiveness reflects an individual’s ability to confidently uphold their own opinions, advocate for their needs, and respect others’ autonomy [39]. The interplay between these two forces shapes collective opinion. While social influence drives consensus, self-assertiveness preserves diversity, creating a dynamic balance in communities.

The goal of this study is to develop the Dialogue Tool that can intuitively present the relationship between individual behaviours (such as conformity and assertiveness) and group dynamic (such as social categorisation) based on the extended HUMAT framework. By simulating the dynamic interaction between social influence and self-assertiveness, the Dialogue Tool can not only show the possible outcomes of group interaction, but also identify potential risks in the community.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Extension of the HUMAT Architecture

3.1.1. Integration of Group Categorisation

Our model of group categorisation is based on the Sinus Milieus framework, which was developed by the Sinus Institute over 40 years ago [40]. This model divides people into groups based on the value orientations and social characteristics of individuals. It has a unique dual-axis visualisation representation system, with the vertical axis measuring social status from low to high, and the horizontal axis reflecting value orientations from traditional to postmodern [41].

To adapt the classic Sinus Milieus model to be more suitable for understanding group differences in democratic decision-making, we make two adjustments: (1) replace the original value orientation dimension with “progressive–conservative” (from reform to traditional), which more accurately reflects individuals’ attitudes towards change [42]; (2) introduce “personal influence” to replace the social status dimension, which considers factors such as education, economic resources, and social networks. These adjustments make the model particularly suitable for analysing the dynamic characteristics of democratic systems: the progressive–conservative dimension captures the openness of different groups to change, while the individual influence assesses the actual ability of various social members, including minority groups, to shape public opinion.

We have simplified these two dimensions into two operational parameters for individual agents in our model: (1) “Openness to change”, representing willingness to accept new ideas, and (2) “Vocalisation”, reflecting an individual’s capacity to influence others. This streamlined approach enables us to categorise different agent and group types, quantify a group’s tendency to accept changes, and assess individual impacts on community dynamics—all while maintaining the model’s analytical rigour but making it more practical to apply.

3.1.2. Interplay of Social Influence and Self-Assertiveness

Decision-making is essentially a multi-dimensional process, especially in collective settings. In this study, we focus on the dynamical relationship between social influence () and self-assertiveness () to reveal the mechanism of adaptive decision-making by individuals in group environments.

Social influence is a type of influence that originates from social relationships, such as peers, family, friends, social norms, or some broader situational expectations [38]. It is crucial in forming an individual’s attitude towards what is acceptable to the group within the community. It often drives individuals to conform and encourages them to align their behaviour with group norms in order to gain group approval.

Self-assertiveness refers to the degree to which an individual is certain of his or her own choices, presenting a relatively stable state that encompasses the values, beliefs, and aspirations that form the basis of personal identity. It serves as a guiding star, which can help individuals interpret and cope with external pressures. Even when confronted with strong opposing forces from social environment, allows individuals to maintain consistent with their personal core beliefs and preferences.

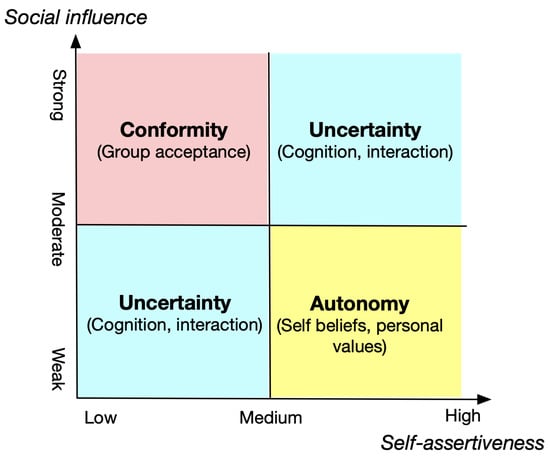

In the complex interplay between and , individuals may adopt the following three strategies, depending on the dynamic balance between the intensity of social influences and their own assertiveness (see Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Interplay between social influence and self-assertiveness.

- Conformity: When individuals face a high levels of social influence and low self-assertiveness, they would take a conformity strategy. That is, individuals would conform to social expectations, even if it means they have to compromise their own preferences. The need for social or group approval often drives this behaviour, especially in high-pressure environments where disagreements can lead to social isolation.

- Autonomy: On the contrary, when individuals hold high self-assertiveness, they tend to stick to their own preferences regardless of the external social influences. That is, when social influence weakens, autonomy emerges, which allows individuals to make independent decisions that reflect their true values. This state is usually associated with high self-assertiveness, as individuals confidently uphold their principles.

- Uncertainty: However, the interplay between social influence and self-assertiveness is rarely direct. Sometimes, people may feel internal conflict, where the influence from both external social pressures and internal personal beliefs creates a state of uncertainty and indecision. This state of conflict can be disorienting, as individuals struggle to reconcile their personal preferences with the expectations of those around them. In uncertain situations, individuals usually adopt two strategies [32]: inquiring and signalling, which would be demonstrated in Section 3.2.2.

3.2. Mechanisms of the Extended HUMAT

3.2.1. Individual Opinion Formation

In community settings, the formation of an individual’s position on a particular proposal is a complex cognitive evaluation process. Based on the HUMAT framework, this process begins with an individual’s evaluation of its own needs and values, which condenses the richness of needs and motivations into three basic categories [32]:

- Experiential needs: This encompasses the direct experience of the situation or an action. This may include factors such as costs and comfort of joining a heating network, visual aspects of windmills, the danger of a car-through park.

- Social needs: In social contexts, people often follow the prevailing social norms in communities and conform to behaviours of others to avoid being socially excluded.

- Values: These values are rooted in a person’s core beliefs and are therefore more stable, less influenced by time, and not directly shaped by personal experiences, such as environmentalism or consumerism.

Initial opinions are shaped by how well the proposal satisfies these three distinct types of needs [43]. In this process, individuals face a complex interaction between personal values and external social pressures, which together shape the final evaluation. It is worth noting that the relative importance of each need varies from person to person. Here, we define individual opinion as a preference measure based on the difference in satisfaction between alternatives, reflecting the decision maker’s preferred choice among possible solutions.

3.2.2. Individual Behavioural Strategy

Mostly, personal experiences are influenced by social influence () and self-assertiveness (). Specifically, individuals compare their and with certain thresholds (self-assertiveness threshold and social influence threshold , both of which range from 0 to 1). Based on the comparison results, individuals will adopt specific behavioural strategies (as shown in Figure 1).

- Conformity: When individuals perceive a lower level of self-assertiveness () compared to the threshold (), and a higher level of social influence () compared to the threshold (), that is, when individuals are in the situation of and , they would align their behaviours with the choices of their peers, reflecting a tendency to conform to prevalent social choices.

- Autonomy: Conversely, when self-assertiveness () exceeds the threshold () and social influence () falls below the threshold (), that is, when individuals are in the situation of and , they would stick to their initial choices regardless of the preferences of others, emphasising personal autonomy in decision-making.

- Uncertainty: When individuals are in uncertain situations, where both and exceed or fall below their respective thresholds, that is, when individuals are in the situation of and or and , they experience internal dissonance, which is characterised by cognitive conflict as they struggle to reconcile external social pressures with their personal beliefs. This tension is often manifested as dilemmas, which can be categorised into two main types: social dilemmas and non-social dilemmas [32,43].

- Social Dilemmas: These dilemmas occur when an alternative (can be interpreted as an option, a solution, or a plan) yields satisfaction of any of the experiential needs or values and dissatisfaction of social needs. It corresponds to a situation in which an individual is convinced that an alternative has sufficient pros, but at the same time, they feel secluded from this view because not enough others in the social network choose the same option. For example, a person may be very much in favour of biking in a city and support investments in cycling infrastructure, fulfilling personal health goals and environmental values, yet face social dissatisfaction due to a majority of peers and fellow citizens being very car-minded.

- Non-Social Dilemmas: These involve conflicts that arise from differences in experience or values. An experiential dilemma may emerge when behaviour and opinions satisfy social needs and align with one’s values but do not meet experiential needs, such as the financial costs and inconvenience of joining a heating network. Conversely, value dilemmas may occur when an individual’s behaviour meets experiential and social needs but conflicts with personal values, such as driving to work for comfort and popularity but in conflict with environmental principles.

The cognitive dissonance stemming from these dilemmas often prompts individuals to take actions to resolve internal conflicts, often through engaging with their social networks to seek out new information to support their position [44]. This social interaction serves as a mechanism for mitigating dissonance, enabling individuals to either seek or provide information that can help clarify their decisions. Two primary strategies can be used to deal with these conflicts:

- Signalling Strategy: This approach promotes exchange of opinions and negotiation by identifying relatively open-minded and more easily persuaded members of the group, thereby reducing feelings of dissonance [45].

- Inquiring Strategy: This strategy requires individuals to actively seek information that reinforces their existing preferences, thereby consolidating their positions and reducing feelings of uncertainty [44].

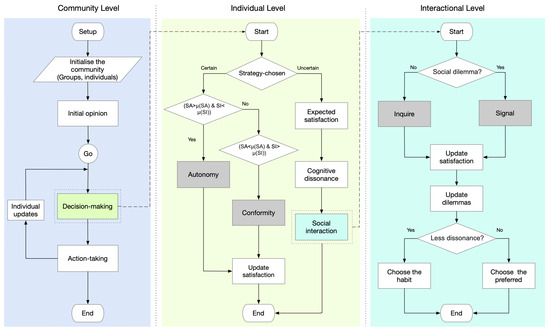

3.3. Decision-Making Process

To understand the decision-making process in the extended HUMAT model, we can analyse it from three interconnected levels: community or group level, individual level, and interactional level. In Figure 2, the elements in the ovals and circles represent the starting or ending points of the process, such as “Start”, “Setup”, and “Go”, which represent the beginning of the next process, and “end”, which represents the end of the above process at this point.

Figure 2.

Process of decision-making of the extended HUMAT.

Moreover, the decision-making process shown therein is not used to show the sequential relationship of the three interrelated levels, but to use the three levels to explain the process in different depths. The process at the individual level is used to explain in more depth and detail what the “decision-making” process at the community level actually includes and what individuals do in this process. Similarly, the “social interaction” process at the individual level is more clearly explained in the process at the interaction level, which explains how individuals interact and how these interactions affect individuals and the entire decision. It is also worth noting that this entire decision-making process iterates at each time step in our model—in other words, all procedures illustrated in Figure 2 are completed once per time unit. These processes are described in details as the following:

- Community or Group Level: We can also call it the collective level. At the initial stage in this level, individuals form their initial opinion on proposals (or plans) based on the satisfaction of their experiential needs and values. This stage is crucial, as it sets the foundation for how individuals perceive and evaluate various proposals. The satisfaction derived from three primary types of needs—experiential, social, and values (stated previously in Section 3.2.1) —significantly influences individual initial attitudes. Collectively, this overall satisfaction informs individuals’ opinions and lays the foundations for the subsequent deliberation.

- Individual Level: Once initial opinions are established, individuals must explore the complex interplay of social influence () and self-assertiveness () before making final decisions. Depending on the balance between these factors, individuals may adopt different strategies (stated previously in Section 3.2.2). For instance, a conformity strategy occurs when individuals prioritise group acceptance. Conversely, an autonomy strategy occurs when individuals emphasise personal autonomy, which allows them to stick to their original beliefs despite external pressures. In cases of uncertainty, individuals may experience internal dissonance, which prompts them to further explore their beliefs and external pressures. Once a clear strategy is chosen and action is taken, individuals will update their satisfaction accordingly.

- Interactional Level: When individuals struggle with cognitive dissonance arising from social and non-social dilemmas, they would go into this level, which is aiming at resolving internal conflicts stemming from the impacts of both personal beliefs and external social influences. Individuals mainly utilise two strategies to mitigate cognitive dissonance: the signalling strategy and the inquiring strategy, which are stated previously in Section 3.2.2 [43]. These strategies reflect a motivated effort to align personal beliefs with social dynamics, ultimately resolving dissonance. Following this dissonance-reduction process, individuals update their levels of cognitive dissonance and dilemma status, which informs whether they shift to a preferred alternative (with lower dissonance) or maintain their current stance (choosing the habitual option).

4. Results

4.1. Towards the Dialogue Tool

4.1.1. Purpose of the Dialogue Tool

In scientific research that employs simulation methods, the goal is often to precisely model real-world phenomena. However, when developing a Dialogue Tool, precisely replicating reality might not be the most effective strategy. Instead, our goal is to integrate this tool into participatory processes, such as democracy labs [23]. This approach allows us to present simulation outcomes that stimulate constructive discussions, thereby fostering a community-oriented mindset.

To address societal concerns regarding polarisation and its impact on democratic processes, our exploration involves magnifying conflicting dynamics and reinforcing social elements. While the simulated social dynamics may be exaggerated, they remain recognisable by touching upon local community features. When individuals see themselves and others represented in the simulation, they may experience a sense of amusement, which can guide discussions toward a more engaging and connected level. Additionally, the Dialogue Tool aims to highlight common views and amplify conflicts without exacerbating them. By clarifying the potential risks of disagreements, the tool may promote consensus and avoid undesirable consequences in the planning process.

Our Dialogue Tool is specifically designed to simulate how opinions and behaviours of individuals (referred to as agents) evolve in response to a community proposal. Its primary goal is to analyse these opinion dynamics, while its secondary goal is to promote discussions about the simulation outcomes, thereby fostering civic inclusivity and engagement.

To ensure broad representation, individuals in the model are categorised in a way that includes minority and disadvantaged groups. As mentioned in Section 3.1.1, our classification is inspired by Sinus Milieus [41]. For simplicity, we focus on two key dimensions: 1: Openness to Change [42]—A person’s willingness to accept and adapt to new developments in various situations, and 2: Vocalisation—The extent to which individuals express and share their opinions and attitudes.

In community decision-making, individuals often face a binary choice, either supporting or opposing a proposal. The level of Openness to Change within the community significantly influences those decisions, especially in cases like urban planning or environmental projects (e.g., wind farms). Some individuals or groups may see the benefits of change (e.g., clean energy) and adopt a positive stance. Others may focus on the negative impacts (e.g., noise, cost) and strongly oppose it. Moreover, Vocalisation plays a key role in such decision-making, as it determines how effectively different groups communicate their perspectives. Ensuring that a wide range of voices are heard is not only the basis for democratic decision-making, but also the key to promoting community satisfaction [46].

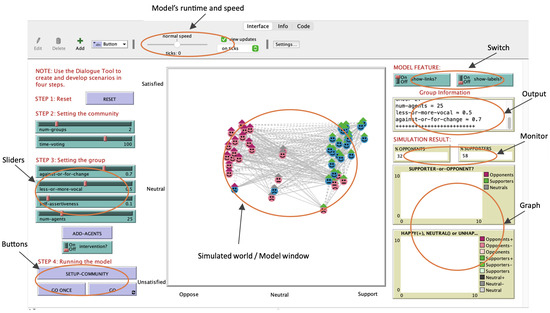

4.1.2. Design of the Dialogue Tool

The simulated community is configured using adjustable parameters (sliders, switches, and buttons; see Figure 3) that define the community structure and individual characteristics. The “sliders” and “switches” control the creation of diverse scenarios. The “buttons” initialise and operate the model. The “output”, “monitor”, and “Graph” display the simulation outcome based on the initial settings.

Figure 3.

Interface of Dialogue Tool through the NetLogo software.

In the middle of the interface lies the “Model window”, a dynamic representation of the simulated community, where each individual is depicted as a distinct node with a unique hat colour, facial expression, and face colour. Hat colours indicate one’s opinion on something: green for support, grey for neutrality, and red for opposition. Facial expressions convey emotions, with a happy face representing satisfaction, a sad face indicating dissatisfaction, and a neutral face showing indifference. Additionally, facial colours distinguish different groups within the community, and lines represent connections between individuals: solid lines for relationships within the same group, and dotted lines for connections between different groups.

In this study, we focus on how individual opinions form and evolve through communication and interactions, which continue until a predefined simulation time is reached (e.g., a voting deadline). By modelling these dynamics, we aim to explore the mechanisms behind opinion shifts and social influence in a structured, interactive environment.

To ensure the clarity and operability of the model, we intentionally made several simplifications. Specifically, (1) the decision-making process does not take into account media influences (such as news or social media) but focuses on direct interactions between individuals; (2) this model only examines the independent impact of a single proposal, does not consider external linkages, and ignores the interdependencies between projects; (3) long-term feedback loops are not included in the analysis, and the study focuses on the evolution of opinions in the short term to keep the analysis controllable and targeted. These simplifications are intended to balance the explanatory power of the model with computational feasibility, while ensuring that the research questions are clearly defined.

4.1.3. Simulation Design

Suppose the local government proposes to build a wind farm and involves the surrounding community in the decision-making process. This proposal initiates a debate involving several considerations, including experiential needs such as noise, shade patterns, and values such as aesthetics, emission (CO2) reductions, and ecological impacts (bird fatalities). As a result, individuals within the community take different positions on this proposal, ranging from support, neutrality to opposition, depending on the combined effect of their expected experiences, values, and the opinions of their friends and neighbours.

Our experiment aims to simulate diverse community dynamics where individuals (represented by heads) participate in decision-making regarding this proposed wind farm. As shown in Figure 3, individuals often hold different opinions (represented by hat colours) and satisfaction (facial expressions). As they interact and influence one another, their positions within the community shift based on two factors: The horizontal position reflects the extent of support for the wind farm, with individuals moving further to the right as they become more supportive. The vertical position represents satisfaction, with individuals positioned higher up as they become more satisfied (see Figure 3).

We explore several key scenarios using this wind farm proposal as an example. In particular, we investigate community dynamics at the time of voting (e.g., at tick 100, when the simulation ends), the support rate for the proposal, and the overall satisfaction of the community. The scenarios include the following: (1) Unsatisfied supporting community: A situation where individuals support the wind farm but many of them remain dissatisfied. (2) Divided community: A polarised community with clear divisions between supporters and opponents. (3) Reconciled community: A community where interactions lead to convergence and consensus.

4.1.4. Calibration of Group Attributes and Individual Variables

In this section, we first outline the process of configuring the community structure under various scenarios, and then the way in which the individual variables are calibrated.

To explore the dynamics and outcomes within the community, we design an artificial community comprising 40 residents. In real life, communities often consist of diverse groups. Here, we adopt a stylised structure featuring two distinct groups: a larger group, “Group Pink” (35 members, represented by pink faces), and a smaller group, “Group Blue” (5 members, represented by blue faces). The simulation runs for 100 rounds, capturing the evolution of individual opinions throughout the voting process. It operates in discrete time steps (ticks) within the NetLogo platform, where each tick represents an abstract time unit corresponding to activities described in Figure 2.

In Scenario 1, we examine a common situation where the larger group is mildly opposed to the wind farm proposal but remains relatively silent and unassertive, whereas the smaller group strongly supports the proposal and is highly outspoken. Briefly, the large group is slightly conservative and hesitant toward change, while the small group is highly open to change and assertive in expressing its opinions. The parameter settings for this scenario are detailed in Table 1. Beyond Scenario 1, we investigate two additional contexts:

Table 1.

Parameter settings for the community in scenario exploration experiments.

Scenario 2: We explore the conditions under which a divided community emerges, specifically examining the role of assertiveness. Here, all parameters remain unchanged except for assertiveness, which increases from 0.1 to 0.2.

Scenario 3: We examine how a divided community can be united through interventions. The parameter settings remain unchanged from Scenario 2, but we introduce an intervention at the mid-point of the simulation (tick 50). This timing ensures sufficient time to observe the effects of interventions on community dynamics without being implemented too early. The intervention is designed to reduce resistance of individuals from the less satisfied group, which, in this scenario, is the Pink Group.

In addition to the four variables listed in Table 1, social influence plays a crucial role in shaping individual opinions. To prevent individual differences from interfering with the results, we assume all individuals experience social influence equally, assigning both groups the same value. To ensure that social influence does not dominate the early stages—potentially limiting individual interactions and information exchange, we deliberately set it at a low initial level (0.1). It then gradually increases by 0.1 every 10 ticks, reaching 1.0 near the end of the simulation (tick 90). This gradual progression allows individuals (in the model) to form opinions before social influence becomes a dominant factor in decision-making.

Regarding decision-making strategies, two key parameters influence the choice of individual strategies: self-assertiveness threshold () and social influence threshold () (see Section 3.2.2). In the aforementioned three scenarios, both thresholds are set to a moderate value of 0.5, ensuring that neither social influence nor self-assertiveness dominates decision-making, thereby avoiding the occurrence of extreme situations.

Having defined the group attributes above, we now detail the individual-level settings. Individual variables include the importance of different needs and initial satisfaction with experiential needs and values related to the wind farm proposal. The key parameter, Openness to Change (see Section 3.1.1), quantifies the initial acceptance of the proposal for each group. This value ranges from 0 to 1, where below 0.5 indicates opposition to the wind farm proposal, and above 0.5 indicates support for the wind farm proposal.

By standardising Openness to Change for each individual, we firstly quantify the degree of support or opposition within each group. We then use a normal distribution to determine individuals’ initial satisfaction levels based on their openness.

Take Scenario 1 as an example, according to the community setting (Table 1). Group Pink (Openness to change = 0.4) exhibits higher satisfaction with opposing the wind farm and lower satisfaction with supporting it. The against-value () reflects the extent of opposition and is calculated using the following equation: = (0.5 − Openness to change)/0.5 = 0.2. For this group, represents the average individual satisfaction regarding experiential needs and values related to opposition, with a standard deviation of 0.5. Conversely, the satisfaction associated with the support value of this group has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 0.5.

In contrast, Group Blue (Openness to change = 1) shows greater satisfaction with supporting the wind farm and lower satisfaction with opposing it. The for-value () illustrates the extent of support for the change and is also normalised according to the Openness to Change parameter, calculated using the equation = (Openness to change − 0.5)/0.5 = 1. For this group, represents the average individual satisfaction regarding experiential needs and values associated with the support, also with a standard deviation of 0.5. In contrast, the satisfaction associated with the opposition value has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 0.5.

Table 2 details the initial satisfaction levels and need importance of individuals in the two groups, where represents Group Pink and represents Group Blue.

Table 2.

Setup for the individual variables.

4.2. Investigation with the Dialogue Tool

4.2.1. Scenario 1: Individual Silence “Silencing” Opposing Opinions

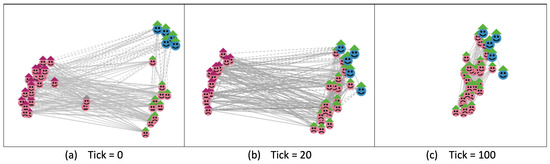

According to the setup of the simulation (Table 1), members of Group Pink (depicted by pink faces) exhibited low assertiveness, as their self-assertiveness parameter is set to 0.1. This limited assertiveness makes individuals less committed to their original opinions and more likely to comply with group norms. Their vocalisation is set to 0.4, indicating that their opinions are less communicated. In contrast, members of Group Blue (depicted by blue faces) displayed significantly high levels of assertiveness, characterised by a self-assertiveness parameter of 1. This strong determination allows them to firmly stick to their positions and not be easily influenced by group norms. Their vocalisation is 1, indicating that their opinions can be clearly heard (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Evolution of support for the plan and community satisfaction in Scenario 1, with pink and blue faces representing members from Group Pink and Group Blue, respectively.

Figure 4 shows the simulation results for this scenario, illustrating how community support for the wind farm proposal evolves at three key points in time (ticks 0, 20, and 100). We can observe from Figure 4 that, at the beginning of the simulation (tick 0), the Pink Group is primarily opposed to the wind farm, while the Blue Group shows strong support. This initial phase shows a sharp contrast between the two groups, with the Pink Group resisting change and the Blue Group advocating for change. As the simulations progress, a clear shift occurs, with many members in the Pink Group transitioning to supporting the wind farm proposal. This result reflects the Blue Group’s strong assertiveness and the impact of being outspoken.

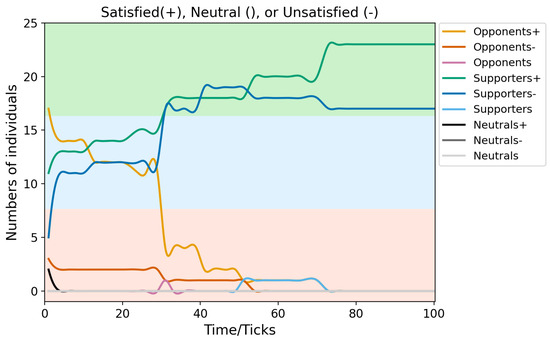

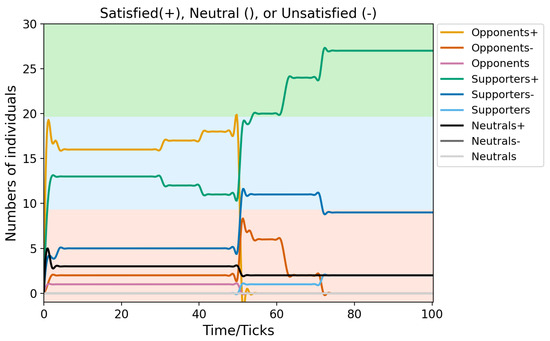

By the end of the simulation (tick 100), as shown in Figure 5 (see also Figure S1), the community’s position on the wind farm proposal has stabilised, and all members (including the Pink Group members that are initially opposed and neutral) eventually turn to a supportive stance. To further analyse the internal structure of the group’s position, Figure 5 also reveals the dynamic distribution of satisfied (+), neutral (), and unsatisfied (-) individuals in the support over time.

Figure 5.

Number of supporters, neutrals, and opponents, along with their emotional states over time in Scenario 1.

The data show that although the support of all is achieved, there is a significant difference in satisfaction within the support camp: among the 40 supporters, 57.5% (23 people, green line) are satisfied with the decision, while 42.5% (17 people, blue line) are dissatisfied despite maintaining their support. This phenomenon of satisfaction and behaviour divergence shows that the decision motivation of a considerable number of supporters may come from social conformity pressure rather than internal preference, and their “support” behaviour is more of an explicit expression of group consensus rather than an active choice based on personal beliefs. This social dynamic process highlights the key difference between “superficial consensus” and “genuine support” in the group decision-making process. Furthermore, the results highlight the influence of assertiveness and voice in shaping community dynamics. As a minority group, members of the Blue Group are able to maintain their initial stance and potentially shape new norms in the community with their high assertiveness, despite the initial normative pressure they face from the larger Pink Group.

In short, the simulation results remind us that the superficial consensus of the community may conceal deep dissatisfaction. This phenomenon warns us when evaluating the acceptance of public policies that, in addition to paying attention to the distribution of explicit stances, it is necessary to monitor implicit indicators such as satisfaction to capture the true acceptance status of community groups, and encourage deeper participation, especially the participation of vulnerable groups.

4.2.2. Scenario 2: Self-Assertiveness May Lead to Polarisation

In Scenario 1, we observed that unassertive individuals tended to conform to their group, resulting in a superficial consensus, which is not an ideal outcome for the community. This raises the following question: What happens if individuals become more assertive about their initial opinions?

To explore this, Scenario 2 examines how a slight increase in individual assertiveness influences community dynamics. The experimental setup remains the same as in Scenario 1, except for one key adjustment: Group Pink’s assertiveness is increased to 0.2, while Group Blue’s parameters remain unchanged.

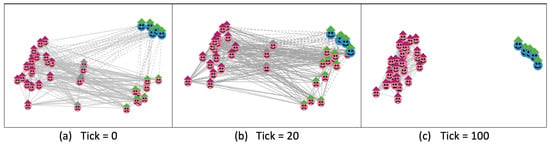

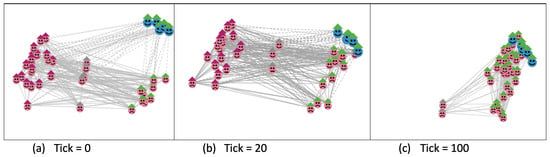

As shown in Figure 6, at the start of the simulation (tick 0), most Group Pink members oppose the wind farm proposal and some members are neutral, while all Group Blue members strongly support it (as the initial state of Scenario 1). Over time (tick 20), interactions between members begin to shift opinions. Some individuals from Group Pink switch to a supporting stance due to the influence of the assertive Group Blue members. However, by the time of voting (tick 100), the community becomes completely divided—Group Pink strengthens its opposition due to its assertiveness and internal group norm, while Group Blue maintains its strong support.

Figure 6.

Evolution of support for the plan and community satisfaction in Scenario 2, with pink and blue faces representing members from Group Pink and Group Blue, respectively.

Figure 7 (see also Figure S2) presents the distribution of supporters, neutrals, and opponents, along with their emotional states. Combining observations from Figure 6 and Figure 7, we observe that all 35 Group Pink members become opponents, with 30 classified as satisfied opponents, 2 as unsatisfied opponents, and 3 as neutral opponents. Meanwhile, all five Group Blue members remain satisfied supporters, resulting in a fully divided community with no neutral individuals remaining.

Figure 7.

Number of supporters, neutrals, and opponents, along with their emotional states over time in Scenario 2.

To further know the outcome of satisfaction levels among opponents and supporters, we refer to Figure 7, which shows that as the simulations progress, Group Pink solidifies its stance as satisfied opponents, reinforcing their internal group identity (see Figure 6). A total of 35 out of 40 individuals (87.5%) in the community reports satisfaction, finding comfort in their own position to the wind farm proposal. This internal satisfaction is driven by a strengthened sense of belonging and a reinforced group identity, despite ongoing discussions. Specifically, 85.7% (30 out of 35) of Group Pink members become satisfied opponents, while 100% of Group Blue members remain satisfied supporters, actively advocating for the wind farm.

The increased assertiveness in Group Pink prevents its members from easily shifting their stance, while Group Blue’s high assertiveness maintains their strong support even in the face of significant social pressure from the larger Group Pink. This dynamic evolution produces an unexpected consequence: the polarisation of the community. As they become firmer in their own views, Pink Group members become more repelled by opinions from different groups and tend to be closed in their social circle. This tendency not only prompts individuals to interact mainly with members of the same group who hold similar views, but also leads to a decrease in the frequency of cross-group communication, thus causing the collapse of the foundation of community cohesion.

As shown in Figure 6, although the simulation results show that overall satisfaction remains at a high level and the solidarity within each group has increased, this local improvement in cohesion actually has a negative impact on the community as a whole. We observed that the increasingly intensified polarisation has led to a deep division between groups with different positions, reducing the frequency of cross-group interaction and exchange of ideas.

This state of division not only weakens the cohesion among community members, but also hinders the possibility of mutual cooperation. What is particularly critical is that this polarised pattern seriously restricts the opportunities for dialogues and the operational efficiency of the community’s collective decision-making mechanism, making the progress of various communal issues, such as wind farm proposals, face major obstacles.

It should be noted that the current study only focuses on the dynamic stage before the final decision. We are also aware that the final decision may trigger two completely different group psychological reactions. For example, whether the wind farm plan is implemented or rejected will directly affect the satisfaction of the two groups: the potential results of the Pink Group and the Blue Group may produce a situation where if the proposal is passed, the Blue Group will feel that they are “winners”, while the Pink Group may feel dissatisfied and feel that they are “losers”. However, we have demonstrated in the design of the Dialogue Tool in Section 4.1.2 that the simulation does not take into account the post-voting dynamics that occur after collective decision-making.

4.2.3. Scenario 3: From Polarisation to Reconciliation

In Scenario 2, a divided community emerged, which is the least desirable outcome for community cohesion. This raises questions: How can such divisions be bridged? And how can they be prevented in the first place?

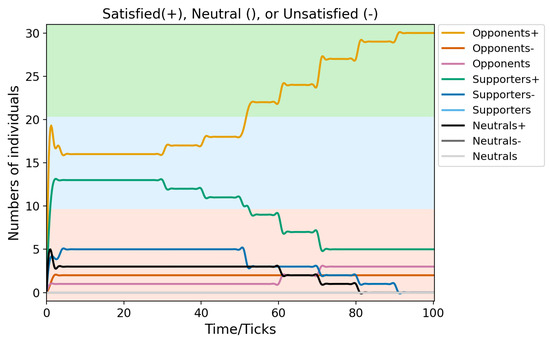

In Scenario 3, we aim to explore the potential of a Dialogue Tool to reconcile a divided community regarding the wind farm proposal. Imagine that, at a certain point, the government intervenes by providing community education on wind farm safety and involving residents in decisions about its placement and visual impact. These actions aim to reduce resistance among the less satisfied group; in this case, Group Pink (represented by pink faces). Specifically, the intervention targets the reduction (by ) of satisfaction associated with opposing the proposal ( and , as shown in Table 2). The simulation maintains the same initial setup as in Scenario 2. However, at tick 50, an intervention is introduced to mitigate Group Pink’s resistance while keeping their assertiveness unchanged.

As shown in Figure 8, the initial simulation mirrors Scenario 2, with Group Pink largely opposing the wind farm and Group Blue strongly supporting it. By tick 50 (Figure 9), the number of supporters and opponents has become more balanced. At this point, the intervention measure is implemented.

Figure 8.

Evolution of support for the plan and community satisfaction in Scenario 3, with pink and blue faces representing members from Group Pink and Group Blue, respectively.

Figure 9.

Number of supporters, neutrals, and opponents, along with their emotional states over time in Scenario 3.

Following the intervention, we observe shifts in community dynamics (Figure 9, see also Figure S3). Starting at tick 50, opposing individuals (represented by the ginger line) begin reconsidering their stance, gradually shifting towards support (green line). Between ticks 50 and 70, the community experienced a period of turbulence: individual stances and satisfaction levels fluctuated. During this phase, more unsatisfied opponents appeared (orange line), as members of Group Pink transitioned to support, leaving remaining opponents feeling isolated due to differing opinions within their social circles (e.g., friends and neighbours adopting different views become supporters). Similarly, an increase in unsatisfied supporters (blue line) is observed, as some individuals supported the wind farm out of conformity rather than genuine belief in the proposal.

As discussions continue and the targeted intervention takes effect, the members who initially hold opposing opinions gradually turn to a supportive position and finally reach an agreement with the mainstream opinion (see Figure 8). It is worth noting that many unsatisfied supporters find satisfaction not necessarily with recognising the value of the proposal itself but through a sense of belonging by conforming to the group.

By the end of the simulation experiment, although the community forms an obvious majority consensus (the support rate reached 95%, 38 out of 40), not all individuals are fully satisfied. Some members of Group Pink express support for the wind farm due to social conformity rather than genuine belief in the project. Although they conform to the majority view within their group, there is still a clear gap between their values and actual experience.

This result highlights the partial effectiveness of targeted interventions in reducing polarisation and promoting community cohesion. Although the intervention successfully facilitates consensus, it also exposes the risk of “superficial consensus”; that is, individuals align with the group without fully addressing their personal concerns. Such phenomenon of “superficial consensus” suggests that decision makers need to establish a more complete public opinion monitoring mechanism, aiming to pay more attention to the real demands of individuals hidden under group pressure while pursuing superficial consensus.

4.2.4. Insights from Comparing the Three Scenarios

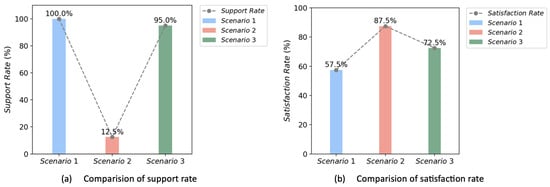

Alongside the simulation results from Section 4.2.1, Section 4.2.2 and Section 4.2.3, we summarise the key findings by analysing Figure 10, as follows:

Figure 10.

Comparison of support and satisfaction across three scenarios.

In Scenario 1, although the support rate for the wind farm plan in the community reaches 100% (Figure 10a), the satisfaction rate is actually only 57.5% (Figure 10b); that is, 42.5% of the supporters were actually dissatisfied with the plan. The reason for this difference is that many individuals do not agree with the plan itself, but support the plan out of conformity and a sense of belonging, especially those with low self-assertiveness who put a sense of belonging above personal preferences. This superficial consensus covers the underlying differences of opinion, highlighting the importance of evaluating policy acceptance alongside satisfaction indicators.

In Scenario 2, a severely divided community emerges, with support rate at only 12.5% (Figure 10a), even though all five members of the Blue Group remain supportive and all 35 members of the Pink Group become opponents. Although each group achieves high internal satisfaction due to the strengthening of group identity, the cohesion of the entire community collapses. Increased self-assertiveness may intensify social divisions, and timely intervention is critical to prevent group isolation and dialogue failure.

In Scenario 3, introducing an intervention at tick 50 raises support from 12.5% to 95% (Figure 10a), though 22.5% ((1–72.5%) in Figure 10b) of supporters conform passively rather than fully agreeing. While opposition decreases, a “satisfaction gap” emerges, as some individuals support the proposal reluctantly rather than through genuine belief. This suggests that while interventions can reduce explicit opposition, they do not always address deeper concerns.

Overall, the key takeaways are as follows:

- Group decision-making is often affected by outspoken individuals, potentially suppressing the views of silent members. Mechanisms need to be designed to encourage marginal voices to express themselves.

- Simply boosting individual assertiveness may intensify conflict. It is necessary to balance self-expression and group cohesion to avoid community polarisation.

- External intervention can change the public’s position, but it may result in “passive conformity” rather than “active belief”. This requires the establishment of an evaluation system that can simultaneously track behavioural stances (support/opposition) and psychological satisfaction.

A final thought: public decision makers need to be cautious of superficial agreement that covers underlying divisions. By transforming simulation-based insights, such as satisfaction fluctuations and group interaction patterns into real-world early warning signals, it becomes possible to foster deep rather than a superficial community integration.

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis

In the previous section, we have presented how the Dialogue Tool can simulate key social dynamics within a community context. While our experiments highlight its potential, the true value of the tool lies in its flexibility. Using the Dialogue Tool yourself gives you the freedom to try different settings, such as more groups of different sizes and attributes.

To explore the sensitivity of support and satisfaction rates, we design an experiment within a simulated community consisting of 40 residents as well. Both groups exhibit mild preferences regarding a given proposal: one group is slightly in favour, while the other is slightly against it. However, the slightly-against group demonstrates lower vocalisation compared to the slightly-for group, as defined by the parameters in Table 3.

Table 3.

Parameter settings for the community in sensitivity analysis experiments.

For the analysis, the social influence threshold () and self-assertiveness threshold () are varied over the values . This analysis aims to determine how changes in these thresholds impact the average of support rate and satisfaction rate within the community. Multiple threshold combinations are tested, and the resulting trends in support and satisfaction rates are tracked over time.

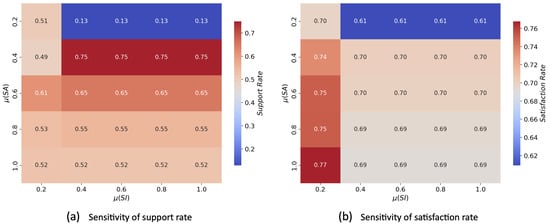

4.3.1. Sensitivity of Support and Satisfaction Without Interventions

Observing Figure 11a, we find that the impact of the social influence threshold () on the support rate presents a segmented feature: when , the support rate remains relatively stable; when , the support rate decreases significantly. The optimal support rate occurs when . As for the self-assertiveness threshold (), its relationship with the support rate presents a pattern: when the assertiveness threshold is very high () or very low (), it will lead to a decrease in the support rate, while the moderate values () correspond to higher support. Figure 11b reveals the changing pattern of satisfaction rate: when both thresholds are not too low (≥0.4), the satisfaction rate remains stable; when , the satisfaction rate is the lowest no matter what the is, except for when both thresholds are at the lowest; when , it tends to reduce the satisfaction rate.

Figure 11.

Sensitivity of support and satisfaction from the thresholds for social influence () and self-assertiveness () without interventions.

It is worth noting that there is a dynamic relationship between support and satisfaction: When , the Pearson correlation coefficient between the two indicators is 0.2685, which indicates a weak positive linear relationship. When , they become positively correlated (high support and high satisfaction). Moderate values for assertiveness threshold () can optimise both support and satisfaction, and balance the needs of different groups.

Above all, we have the following recommendations: To achieve maximum satisfaction, adopt a low social influence threshold (). If support rate is a priority, use a moderate assertiveness threshold () with a high social influence threshold (). Avoid extreme threshold combinations (extremely high or very low values for both parameters), as they are associated with lower support rates.

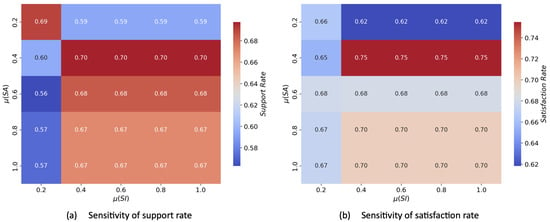

4.3.2. Sensitivity of Support and Satisfaction with Interventions

When interventions are introduced, both support and satisfaction rates become less sensitive to changes in assertiveness () and social influence () thresholds. Compared to scenarios without interventions in Figure 11, the differences of support and satisfaction rate between various threshold combinations become smaller (Figure 12, with interventions).

Figure 12.

Sensitivity of support and satisfaction from the thresholds for social influence () and self-assertiveness () with interventions.

By observing Figure 12a, we find that the impact of the social influence threshold () on support rate maintains similar patterns: it remains stable when but decreases when . Meanwhile, the self-assertiveness threshold continues to show the best results at moderate levels (), with both lower and higher values leading to a reduction in support.

The satisfaction rate behaves differently with interventions, by observing Figure 12b. While less sensitive overall, it shows more variation with different assertiveness threshold () values. Satisfaction peaks at , while both higher or lower value of leads to a decline. Regarding the impact of social influence threshold (), the satisfaction rate follows a segmented pattern: When , the satisfaction remains the same when it increases; when , satisfaction rises with up to 0.6 and then declines. This suggests that, while the intervention helps stabilise outcomes, it does not eliminate all threshold-dependent variation in satisfaction.

For optimal results, we recommend using moderate assertiveness thresholds () combined with high social influence thresholds (). Like the without-intervention scenario, this combination works well for maximising support. As for the optimal satisfaction, considering a moderate can help achieve the goal. The findings show that interventions reduce extreme variations while maintaining the benefits of balanced threshold settings, showing the interventions’ role in mitigating sensitivity to individual or group behaviours.

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of the Simulation Results

Through simulations of the three scenarios, respectively “unsatisfied community” (Scenario 1), “divided community” (Scenario 2), and “reconciled community” (Scenario 3), we gain insight into the dynamics of community engagement and decision-making, particularly in the context of contentious plans. These scenarios reflect how different groups in a community may hold different views and experience different outcomes depending on whether a plan (such as a wind farm proposal) is implemented or not, and how it is implemented. The simulations focus on interactions between community members, specifically how they differ in three dimensions: openness to change, ability to speak up, and the assertiveness of their own views. By analysing these interactions, the simulation reveals key factors that influence community satisfaction, cohesion, and consensus.

In the unsatisfied community (Scenario 1), the Pink Group (represented by pink faces) as the majority, who initially opposed the proposal, eventually compromised and supported the wind farm proposal. The findings highlight two key insights: (a) Blue Group (represented by blue faces), as an assertive minority, influenced the majority opinion with a highly consistent and firm stance, confirming the theory of minority influence in social psychology [47]; (b) individuals with limited voice and assertiveness tend to conform to the mainstream group’s opinions, even if they do not agree with them in their hearts. It is worth noting that the over-assertiveness of the supportive Blue Group led to the neglect of the demands of the opponents, ultimately resulting in a “superficial consensus” situation between the two sides. Such outcomes highlight the importance of dynamic monitoring of group satisfaction during the implementation of sustainable development projects: even if the attitudes of the opposing group change, continuing to track their potential demands and establishing a flexible feedback mechanism can still improve the overall community satisfaction.

The divided community (Scenario 2) illustrated a significant polarisation in community dynamics. As the assertiveness of the Pink Group increased, their original position became more entrenched, leading to a more determined opposition to the proposal, while the Blue Group maintained its original support. This phenomenon shows that increased assertiveness can inhibit the flexibility of individual opinions and reduce the possibility of compromise, which in turn results in social isolation, forms an “Echo Chamber” [48], hinders cooperation between groups, and makes it difficult to reach consensus. Such outcomes serve as a warning for potential social damage due to disputes over a plan.

In the reconciled community (Scenario 3), the simulation indicated that the introduction of targeted interventions successfully mitigated the opposition of the Pink Group, leading to a gradual shift in Group Pink’s stance toward support for the proposal. However, some members of the Pink Group expressed support but dissatisfaction, which highlights the complexity of reaching a genuine consensus. Their alignment with Group Blue may be driven by social conformity rather than personal belief, emphasising the importance of addressing deeper emotional needs. Such outcomes highlight the importance of monitoring the outcomes for more vulnerable groups in a community as well, even when a large majority expresses their support.

Community dynamics are characterised by fluidity and instability. While temporary consensus may be achieved in some cases, without continued recognition of individual concerns, it is easy to go back to the state of division [49]. It is worth noting that, whether using this Dialogue Tool or in real life, once a vote is cast, the result is usually fixed. However, after the vote, individual attitudes may continue to fluctuate between opposition and support, although this phenomenon is not the focus of this article.

5.2. Reflections and Recommendations

The main goal of the Dialogue Tool is not to perfectly replicate real-life scenarios, but to create diverse simulations to reveal the opinion dynamics in communities under specific constraints and their potential outcomes [19], thereby promoting meaningful discussions regarding the impact of different community dynamics and decision-making processes.

Our study sheds light on the complex dynamics of opinion formation and reveals the interplay between individual opinions, group dynamics, and social influences [50]. We found that under the influence of group pressure, individuals may experience a process of attitude change from opposition to support. In this process, minority opinions are often gradually marginalised due to social conformity, and finally form a spiral of silence [51], where diverse opinions are suppressed. Notably, some supporters continue to express dissatisfaction, highlighting the gap between superficial consensus and genuine belief. The Dialogue Tool, for instance, proves effective in amplifying marginalised voices often excluded from planning processes.

Meanwhile, we recognise the trade-off between balancing superficial consensus with addressing deeper emotional or value-based concerns of dissenting groups. While superficial consensus may sometimes be necessary to move a project forward, genuine support is more crucial in the long run. In some cases, initial resistance may even evolve into true support as stakeholders engage more deeply. However, unresolved dissatisfaction, even amid apparent agreement, can weaken social cohesion. If a community accepts an outcome that conflicts with its core values, this dissatisfaction may resurface in future planning efforts as stronger opposition. To address this risk, we recommend that community projects begin with an inventory of individual perceptions, such as interviews or anonymous surveys, conducted before group discussions take place. This helps ensure that all voices are heard, including those less likely to speak up in a group setting, and reduces the likelihood that social pressure will distort the true range of opinions during deliberation.

Additionally, our findings show the detrimental effects of polarisation on community cohesion and progress [52]. While localised solidarity may benefit certain groups, they ultimately hinder the collaboration of the entire community and its collective decision-making. Importantly, our observations suggest that interventions aimed at mitigating resistance can facilitate reconciliation within polarised communities [53]. We further confirmed that group division has detrimental effects on community cohesion and development process. It is worth noting that intervention activities (educational programs, such as ACTIPLEX, https://socialpolarisation.eu, accessed on 1 October 2024) aiming at mitigating resistance can facilitate reconciliation in polarised communities. This evidence shows that consensus is more likely to emerge when interventions actively promote dialogues and address community concerns [54].

In terms of modelling and experimentation, our approach serves not only as an empirical validation tool but also as a theoretical exploration of complex opinion dynamics. Whereas much more elaborated implementations of the HUMAT framework are available [35], the current stylised Dialogue Tool is consistent with the existing theoretical framework and observed social dynamics, and hence, has preliminarily verified its reliability. The adaptable design of the tool enables it to flexibly adapt to different community environments and become a tool to anticipate possible opinion dynamics on community planning processes. At the same time, its educational function helps participants quickly grasp the complexity of group decision-making and raise their awareness of how different subgroups, in particular vulnerable groups, play a role in community discussions and how their satisfaction is under the influence of processes such as social pressure and conformity.

In terms of practical application, the Dialogue Tool allows users to simulate different scenarios through adjustable settings, helping seminar participants anticipate conflicts, develop prevention strategies, and improve decision-making foresight. A major strength of the tool is its ability to rebalance community discussions, which often favour highly educated voices, by highlighting impacts on vulnerable groups. This encourages more privileged participants to consider the needs of the entire community. Preliminary tests show that even with a simple interface, different types of users (including students, government officials and community leaders) can quickly start. Typical cases show that users can complete community issue modelling within one hour and significantly improve their understanding of the key role of neutral groups and the phenomenon of “implicit support”. Based on the follow-up plan of the INCITE-DEM project (https://incite-dem.eu, accessed on 1 October 2024) this tool will verify its effectiveness in promoting democratic processes in a wider range of deliberation scenarios.

For optimising the effectiveness of community governance, we have the following recommendations: first, through simulation experimentations, promote members’ cognitive transformation, help members establish a social system perspective, and understand the relationship between individual choices and group effects; second, improve the decision-making mechanism, establish a minority opinion protection system, and weaken the pressure of conformity; finally, implement targeted intervention, organise information sessions to address concerns of people, and optimise the usability of the tool.

5.3. Limitations and Future Work

The current implementation of the Dialogue Tool is built on agent-based simulations, which, while powerful, come with inherent limitations. One key limitation is the abstraction of real-life complexity into simplified assumptions [55]. Although this simplification helps to illustrate basic behavioural interaction patterns, it may not fully capture key factors such as human emotions, social networks, socio-political contexts, or other external factors that influence decision-making in real communities. While this simplification improves the tool’s ease of use, it also limits its ability to fully reproduce the real complexity of decision-making processes. To this end, we develop a very simple interface for citizens to play with and a more elaborate interface for policy-makers having a deeper interest in testing a larger variety of cases.

In terms of empirical verification, although the underlying HUMAT framework has been applied in multiple community dynamics research projects (PHOENIX, https://phoenix-horizon.eu; CHORIZO, https://chorizoproject.eu; URBANE, https://www.urbane-horizoneurope.eu; INNOAQUA, https://innoaquaproject.eu; PRO-CLIMATE, https://pro-climate.eu, accessed on 1 October 2024), and successfully reproduced real cases such as the transformation of Groningen Park [35], it still remains a challenge applying this framework in the context of complex social dynamics, and in particular, the predictive use of models in such situations is fundamentally limited [56]. Hence, it remains unclear how closely the simulated dynamics reflect actual community behaviours and attitudes, particularly in situations such as wind farm development or other public decisions. It should be emphasised that the core value of this tool is not accurate prediction, but to promote dialogues, exchange multiple perspectives and reflect on implications of planning processes on the social cohesion in a community. The Dialogue Tool simulates possible scenarios and then supports constructive discussions among different interest groups.

Additionally, the current tool focuses on short-term interactions leading up to a decision but does not account for long-term shifts in public opinion after policies are implemented. It does not include post-decision dynamics regarding how community satisfaction or dissent might evolve. However, people often adapt to new situations, and while the initial implementation of a plan may face opposition, they tend to get used to the changes over time. For example, the closure of a park for car traffic in Groningen was very much contested (the pro-closure group won a referendum by 50.9%), but 25 years later, a massive majority (almost 94%) indicated to be in favour of a car-free park [35]. For direct dialogues in communities, such a long-term perspective might be less relevant to discuss, as predicting the public’s acceptance of a policy in 25 years often does not help to resolve the current focus of controversy. However, for policymakers reflecting on long-term developments, it may be interesting to have a tool that helps to envisage long-term effects of policies and provide a reference for formulating more forward-looking public policies.

Future research can be further expanded in three directions: first, develop long-term dynamic simulation functions to extend the research perspective from before decision-making to the evolution of public opinion after policy implementation; second, incorporate external variables such as media influence and expert opinions to improve the model’s ability to depict the complexity of reality; finally, optimise the user interface design to seek a better balance between model accuracy and ease of operation. It should be pointed out in particular that function expansion must follow the principle of “user-friendliness first”. The feedback we have obtained from practice shows that even the current simplified version can stimulate stakeholders to have in-depth discussions on its behaviour patterns, which provides valuable reference for the continuous improvement of the tool.

5.4. Conclusions