Going Green for Sustainability in Outdoor Sport Brands: Consumer Preferences for Eco-Friendly Practices

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Eco-Friendly Practices

2.2. Conjoint Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

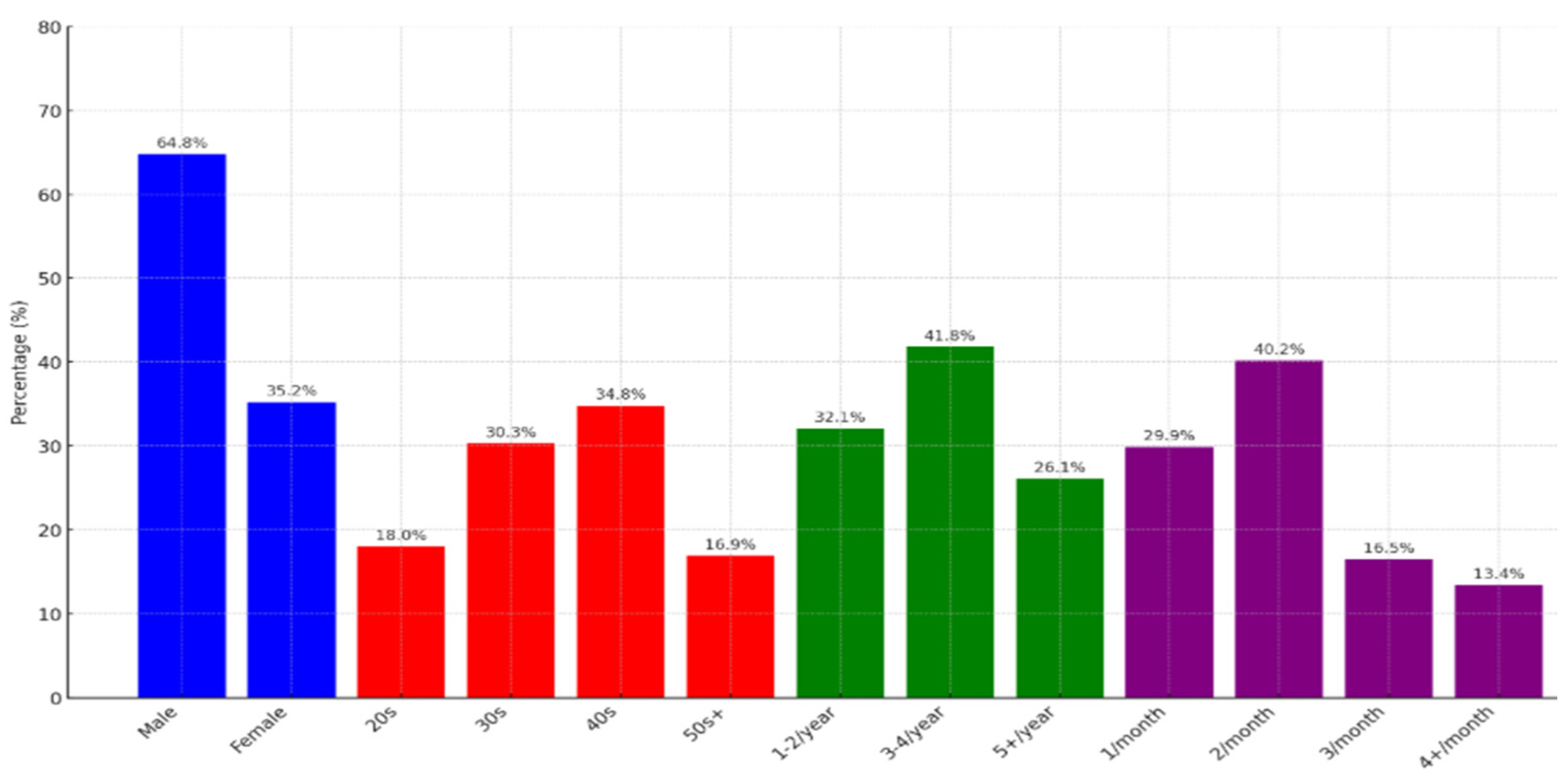

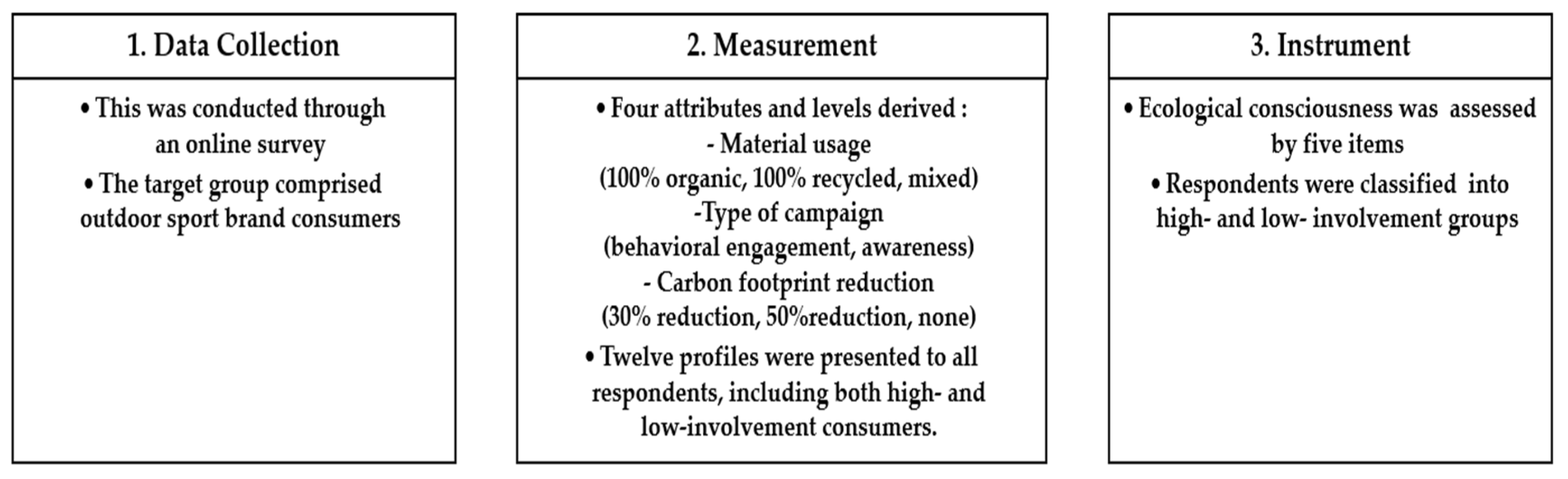

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measurement

3.3. Instrument

4. Results

4.1. Aggregate Conjoint Analysis

4.2. Conjoint Analysis by Involvement

4.3. The Optimal Combination of Eco-Friendly Practices in Outdoor Sport Brands

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rizwan, M.; Siddiqui, H. An Empirical study about green purchase intentions. J. Sociol. Res. 2014, 5, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suki, N.M.; Azman, N.S. Impacts of corporate social responsibility on the links between green marketing awareness and consumer purchase intentions. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 37, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, A.H.; Shehata, H.S.; Mahmoud, H.M.E.; Albakhit, A.I.; Almakhayitah, M.Y. The effect of environmentally sustainable practices on customer citizenship behavior in eco-friendly hotels: Does the green perceived value matter? Sustainability 2022, 14, 7167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Ackerman, M.A.; Azzaro-Pantel, C.; Aguilar-Lasserre, A.A. A green supply chain network design framework for the processed food industry: Application to the orange juice agrofood cluster. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2017, 109, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M.T.; Mazhar, M.; Samreen, I.; Tauqir, A. Economic complexities and environmental degradation: Evidence from OECD countries. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 24, 5846–5866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, M.; Muhs, C.; Neves, M.C.; Cardoso, L.F. Green marketing: A case study of the outdoor apparel brand Patagonia. Responsib. Sustain. 2023, 8, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udeh, E.; Dugba, A. An analysis of the potential integration’s of sustainability into marketing strategies by companies. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2024, 9, 71–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morán-Gámez, G.; Fernández-Martínez, A.; Biscaia, R.; Nuviala, R. Measuring green practices in sport: Development and validation of a scale. Sustainability 2024, 16, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossen, M.; Kropfeld, M.I. “Choose nature. Buy less.” Exploring sufficiency-oriented marketing and consumption practices in the outdoor industry. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 30, 720–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xu, Y.; Lee, H.; Li, A. Preferred product attributes for sustainable outdoor apparel: A conjoint analysis approach. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 29, 657–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostermeyr, L.; Walch, M. GO GREEN!: A Qualitative Study on Environmentally Responsible Consumption in the Outdoor Industry. Master’s Thesis, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden, May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, H.; Fowler, D.C.; Chang, H.J.; Jai, T.C. The effects of sustainability perceptions on perceived values and brand love for outdoor versus fast fashion apparel brands. In Proceedings of the International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference Proceedings, Virtual, 1 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, J.; Jeon, H. The impact of eco-friendly practices on Generation Z’s green image, brand attachment, brand advocacy, and brand loyalty in coffee shop. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, D.; Hwang, S. Factors influencing the college skiers and snowboarders’ choice of a ski destination in Korea: A conjoint study. Manag. Leis. 2009, 14, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.; Baek, S. The relative importance of servicescape in fitness center for facility improvement. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Qui, Y. Research and analysis of outdoor clothing brands under the concept of sustainability. Arts Stud. Crit. 2024, 5, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, M.; Hovemann, G. Consumer preferences for circular outdoor sporting goods: An adaptive choice-based conjoint analysis among residents of European outdoor markets. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2022, 11, 100556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, T.; Ganak, J.; Summers, L.; Adesanya, O.; McCoy, L.; Liu, H.; Tai, Y. Understanding perceived value and purchase intention toward eco-friendly athleisure apparel: Insights from US millennials. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Medeiros, J.F.; Ribeiro, J.L.D.; Cortimiglia, M.N. Influence of perceived value on purchasing decisions of green products in Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 110, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.B.; Chai, L.T. Attitude towards the environment and green products: Consumers’ perspective. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2010, 4, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Benito, J.; González-Benito, O. A review of determinant factors of environmental proactivity. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2006, 15, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malini, H.; Lie, M. The influence of eco-friendly practices, green brand image, and green initiatives toward purchase decision (study case of Starbucks Ayani Mega Mall Pontianak). Tanjungpura Int. J. Dyn. Econ. Soc. Sci. Agribus. 2021, 2, 40–53. [Google Scholar]

- Sellitto, M.A.; Luchese, J.; Bauer, J.M.; Saueressig, G.G.; Viegas, C.V. Ecodesign practices in a furniture industrial cluster of southern Brazil: From incipient practices to improvement. J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manag. 2017, 19, 1750001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swathi, A.; Johnpaul, M. Eco-friendly practices impact on organizational climate: Fostering a sustainable work culture. In Green Management Approaches to Organizational Behavior; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 145–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Burbano, V.C. The drivers of greenwashing. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 54, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Montgomery, A.W. The means and end of greenwash. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Ko, S. The impact of environmentally friendly product design attributes of a sports brand on brand attitude, brand image, and purchase intention. Korea J. Sports Sci. 2023, 32, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.; Choi, K. Factors influencing choice when enrolling at a fitness center. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2018, 46, 1043–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, D.H. Evaluating potential brand associations through conjoint analysis and market simulation. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2004, 13, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omre, B. Formulating Attributes and Levels in Conjoint Analysis; Sawtooth Software Research Paper Series; Sawtooth Software: Sequim, WA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, V.R. Applied Conjoint Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Solano, A. Marketing Indoor Plants as Air Cleaners: A Choice-Based Conjoint Analysis. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Florida, Florida, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Blamey, R.; Bennett, J.; Louviere, J.; Morrison, M.; Rolfe, J. Attribute causality in environmental choice modelling. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2002, 23, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarwater, I.; Kim, B. Sustainable materials in outdoor gear design: An investigation of the future of alternative textiles in outdoor gear design. In Proceedings of the Industrial Designers Society of America Education Symposium, New York, NY, USA, 23–25 August 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Schulte, I.; Ferrari, I. Circularity in Outdoor Textile Brands—Examining the Integration of Brand Identity, Management Actions, and Communication Strategies for Sustainability. Master’s Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Slutz, K. Critical Analysis of Sustainability Strategies in Outdoor Industry Companies. Master’s Thesis, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ, USA, December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchherr, J.; Piscicelli, L.; Bour, R.; Kostense-Smit, E.; Muller, J.; Huibrechtse-Truijens, A.; Hekkert, M. Barriers to the circular economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecol. Econ. 2018, 150, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohune, L. Stepping Lightly: A Case Study on Patagonia’s Corporate Environmental and Social Responsibility Marketing Strategy. Bachelor’s Thesis, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, CA, USA, March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Oppewal, H.; Vriens, M. Measuring perceived service quality using conjoint experiments. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2000, 18, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, A.; Ekdahl, F.; Bergman, B. Conjoint analysis: A useful tool in the design process. Total Qual. Manag. 1999, 10, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, W. The Conjoint Analysis of Purchasing Decision Factor Focused on Sports Shoes. Ph.D. Dissertation, Yonsei University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, S.; Malhotra, G.; Chatterjee, R.; Abdul, W.K. Ecological consciousness and sustainable purchase behavior: The mediating role of psychological ownership. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2022, 35, 414–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, V. Multi generations in the workforce: Building collaboration. IIMB Manag. Rev. 2012, 24, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bick, R.; Halsey, E.; Ekenga, C.C. The global environmental injustice of fast fashion. Environ. Health 2018, 17, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, B. Sustainable fashion supply chain: Lessons from H&M. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6236–6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadesus-Masanell, R.; Crooke, M.; Reinhardt, F.; Vasishth, V. Households’ willingness to pay for ‘green’ goods: Evidence from Patagonia’s introduction of organic cotton sportswear. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2009, 18, 203–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertz, M.; Karakas, F.; Sarigöllü, E. Exploring pro-environmental behaviors of consumers: An analysis of contextual factors, attitude, and behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3971–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Eco-Friendly Practices | Outdoor Sport Brands |

|---|---|

| Sustainable and recycled materials | Arc’teryx, Columbia, Fjällräven, Icebreaker Klattermusen, Patagonia, Mammut, REI, The North Face, Pinewood, Tentree, Marmot |

| Eco-friendly campaign | Arc’teryx, Fjällräven, Icebreaker, Klattermusen, Mammut, Patagonia, REI, The North Face |

| Eco-friendly manufacturing | Arc’teryx, Columbia, Cotopaxi, Fjallraven, Icebreaker, Mammut, Patagonia, REI, Tentree, The North Face, VAUDE |

| Environmental conservation donation | Arc’teryx, Columbia, Cotopaxi, Mammut, Patagonia, prAna, REI, The North Face |

| Eco-Friendly Practices | Attributes | Level |

|---|---|---|

| Sustainable and recycled materials | Material usage |

|

| ||

| ||

| Eco-friendly campaign | Type of campaign |

|

| ||

| Eco-friendly manufacturing | Carbon footprint reduction |

|

| ||

| ||

| Environmental conservation donation | Implementation of donation |

|

|

| Profiles | Material Usage | Type of Campaign | Carbon Footprint Reduction | Implementation of Donations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100% recycled materials | Consumer behavioral engagement campaign | Reducing 30% by 2030 | Implemented |

| 2 | 100% organic materials | Consumer behavioral engagement campaign | Reducing 30% by 2030 | Implemented |

| 3 | Blended materials (50% recycled + 50% organic) | Consumer behavioral engagement campaign | Reducing 30% by 2030 | Implemented |

| 4 | 100% organic materials | Consumer behavioral engagement campaign | No reduction | Not Implemented |

| 5 | Blended materials (50% recycled + 50% organic) | Consumer behavioral engagement campaign | Reducing 50% by 2030 | Implemented |

| 6 | Blended materials (50% recycled + 50% organic) | Consumer behavioral engagement campaign | Reducing 30% by 2030 | Implemented |

| 7 | 100% recycled materials | Consumer behavioral engagement campaign | No reduction | Implemented |

| 8 | Blended materials (50% recycled + 50% organic) | Consumer awareness enhancement campaign | Reducing 50% by 2030 | Implemented |

| 9 | Blended materials (50% recycled + 50% organic) | Consumer behavioral engagement campaign | Reducing 30% by 2030 | Not Implemented |

| 10 | 100% organic materials | Consumer behavioral engagement campaign | Reducing 50% by 2030 | Not Implemented |

| 11 | 100% recycled materials | Consumer behavioral engagement campaign | No reduction | Not Implemented |

| 12 | Blended materials (50% recycled + 50% organic) | Consumer awareness enhancement campaign | Reducing 50% by 2030 | Not Implemented |

| Construct | Scale Items | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|

| Ecological consciousness |

| 0.821 |

| 0.788 | |

| 0.754 | |

| 0.722 | |

| 0.699 | |

| Cronbach α | 0.768 | |

| KMO Measure of Sampling Adequacy = 0.832; Bartlett’s test of sphericity = 462.449; df = 3, sig = 0.000. | ||

| Construct | Classification | Involvement Value (Mean) | Number of Consumers (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ecological consciousness involvement | High-ecological consciousness | 4.26 (3.42) | 157 (60.2) |

| Low-ecological consciousness | 2.74 (3.42) | 104 (39.8) |

| Attributes | Level | PWU | RI (%) | Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material usage |

| 0.420 −0.636 0.216 | 36.268 | 1 |

| Type of campaign |

| 0.541 −0.541 | 29.564 | 2 |

| Carbon footprint reduction |

| 0.232 0.362 −0.594 | 21.261 | 3 |

| Implementation of donations |

| 0.287 −0.287 | 12.907 | 4 |

| Pearson’s R = 0.869 (p < 0.001) | ||||

| Attributes | Level | PWU | RI (%) | Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material usage |

| 0.454 −0.570 0.116 | 37.500 | 1 |

| Type of campaign |

| 0.413 −0.413 | 18.402 | 3 |

| Carbon footprint reduction |

| 0.211 0.408 −0.619 | 28.317 | 2 |

| Implementation of donations |

| 0.312 −0.312 | 15.781 | 4 |

| Pearson’s R = 0.873 (p < −0.001) | ||||

| Attributes | Level | PWU | RI (%) | Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material usage |

| 0.336 −0.517 0.181 | 34.689 | 1 |

| Type of campaign |

| 0.398 −0.398 | 32.473 | 2 |

| Carbon footprint reduction |

| 0.207 0.401 −0.608 | 19.167 | 3 |

| Implementation of donations |

| 0.165 −0.165 | 13.671 | 4 |

| Pearson’s R = 0.881 (p < 0.001) | ||||

| Attributes | Level | PWU | RI (%) | PWU*RI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material usage |

| 0.383 −0.599 0.216 | 36.268 | 0.139 −0.217 0.078 |

| Type of campaign |

| 0.341 −0.341 | 29.564 | 0.101 −0.101 |

| Carbon footprint reduction |

| 0.202 0.342 −0.544 | 21.261 | 0.043 0.073 −0.116 |

| Implementation of donations |

| 0.207 −0.207 | 12.907 | 0.027 −0.027 |

| ||||

| Attributes | Level | PWU | RI (%) | PWU*RI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material usage |

| 0.404 −0.644 0.240 | 37.500 | 0.151 −0.241 0.090 |

| Type of campaign |

| 0.413 −0.413 | 18.402 | 0.076 −0.076 |

| Carbon footprint reduction |

| 0.223 0.360 −0.583 | 28.317 | 0.063 0.102 −0.165 |

| Implementation of donations |

| 0.312 −0.312 | 15.781 | 0.049 −0.049 |

| ||||

| Attributes | Level | PWU | RI (%) | PWU*RI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material usage |

| 0.336 −0.517 0.181 | 34.689 | 0.117 −0.179 0.062 |

| Type of campaign |

| 0.398 −0.398 | 32.473 | 0.129 −0.129 |

| Carbon footprint reduction |

| 0.197 0.318 −0.515 | 19.167 | 0.038 0.061 −0.099 |

| Implementation of donations |

| 0.165 −0.165 | 13.671 | 0.023 −0.023 |

| ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jang, W.-Y.; Choi, E.-Y. Going Green for Sustainability in Outdoor Sport Brands: Consumer Preferences for Eco-Friendly Practices. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4320. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104320

Jang W-Y, Choi E-Y. Going Green for Sustainability in Outdoor Sport Brands: Consumer Preferences for Eco-Friendly Practices. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4320. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104320

Chicago/Turabian StyleJang, Won-Yong, and Eui-Yul Choi. 2025. "Going Green for Sustainability in Outdoor Sport Brands: Consumer Preferences for Eco-Friendly Practices" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4320. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104320

APA StyleJang, W.-Y., & Choi, E.-Y. (2025). Going Green for Sustainability in Outdoor Sport Brands: Consumer Preferences for Eco-Friendly Practices. Sustainability, 17(10), 4320. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104320